Michaela Greer, Jacqueline Lytle, Emalee Shrewsbury, and Kevin Dvorak

Nova Southeastern University

Introduction

During the 2017-2018 academic year, Nova Southeastern University (NSU) opened a new Writing and Communication Center (WCC) designed to offer assistance to all 20,000 NSU students. A private, not-for-profit institution, NSU is one of only 37 universities to have Carnegie classifications as both “high research activity” and “community engaged.” Approximately 75% of NSU students are at the graduate and professional levels, and the university has eight locations: seven in Florida and one in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The largest campus, located in Fort Lauderdale, has over 10,000 students and is the physical home for the WCC.

The WCC has two locations on the Fort Lauderdale campus–a 3,000 sq. ft. center in the university’s largest library and a small satellite (approx. 100 sq. ft.) university’s Health Professions Division library. The WCC also has satellite locations at two branch campuses–Miami and Ft. Myers, each of which are typically open one day per week. In addition, the WCC offers about 75 hours per week of online consulting.

The new WCC staff was comprised of the following:

● 1 Executive Director

● 3 Faculty Coordinators

● 5 Graduate Assistant Coordinators

● 7 Professional Writing Consultants (part-time)

● 13 Graduate Peer Writing Consultants

● 30 Undergraduate Peer Consultants

Thus, the WCC had over 50 staff members providing writing and communication assistance via four physical locations and online. Because of the size and diversity of our staff, we recognized that the kairos for our consultant training (Glover, 2006) would require us to be creative and offer opportunities through a variety of formats.

We begin each academic year with two days of training prior to the first day of fall classes. However, in order to accommodate our staff members’ need for ongoing education and training, we created a series of online learning modules our writing consultants could complete during their work hours. New staff members would complete them prior to working one-on-one with students (in person or online), and returning consultants would go through the series as a refresher. Returning consultants, we should add, would also be asked to contribute to the development and evolution of the modules. This article shows readers how we developed and implemented these modules, highlights early assessment results from the first semester they were utilized, and offers advice on how other centers, particularly ones with large, diverse staffs that operate in multiple locations, can implement such models.

Foundation for Modules

In order to ensure that our consultants were provided with consistent, meaningful training, we created a series of consultant learning outcomes. Our short-term goal was to develop outcomes that would reflect valued practices in writing and communication center studies and maintain the integrity of our institutional context. Our long-term goal was to develop levels for consultant training, so “Level One” would be for new consultants, “Level Two” for returning, and so forth.

To develop learning outcomes based on best practices in the field, we consulted the following texts:

● The Bedford Guide for Writing Center Tutors

● What Every Writing Tutor Needs to Know

● The Longman Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice

● Tutoring Writing: A Practical Guide for Conferences

● The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors

● ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors – 2nd edition

● Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies

In addition, we reviewed approximately twenty-five writing center—or peer writing tutoring-based—course syllabi located online. To ensure the outcomes fit our institutional context, we reviewed learning outcomes for NSU’s first-year composition program, the university’s Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP), and NSU’s core values.

We created lists of the book chapters, syllabi and program outcomes, and core values. We coded the lists based on categories that emerged. We then grouped coded lists together and narrowed down the focus to the following five learning outcomes:

1. Demonstrate understanding of basic writing center praxis

2. Explain writing as a social and rhetorical activity

3. Recognize grammar as context-based

4. Discuss how genre characteristics are shaped by rhetorical situations

5. Explain multiple research methods

These outcomes, we believe, best represent what our consultants need to be able to do in order to start consulting with students. The outcomes are representative of best practices in the fields of writing centers and writing studies, and they acknowledge our institutional context.

Module Development and Facilitation

After developing the learning outcomes and considering our evolution into the WCC, we returned to the texts to begin developing online modules that would achieve the outcomes and establish a vocabulary to keep our staff on message. For Fall 2017, we had six modules completed and were working toward developing four more. The following would be our first six modules:

1. “NSU Write from the Start Writing and Communication Center”

2. “Being a Consultant or Fellow”

3. “Working with COMP Faculty”

4. “Working in the COMP Classroom”

5. “Studio Session Basics”

6. “Studio Session Strategies”

These modules were designed to be placed in NSU’s online learning management system, Blackboard, where the WCC has its own “course” that all consultants are provided access to. The faculty coordinators and graduate assistants have the ability to control content and monitor assessment, while the rest of the staff can only access the materials.

Scheduling Module Assignments

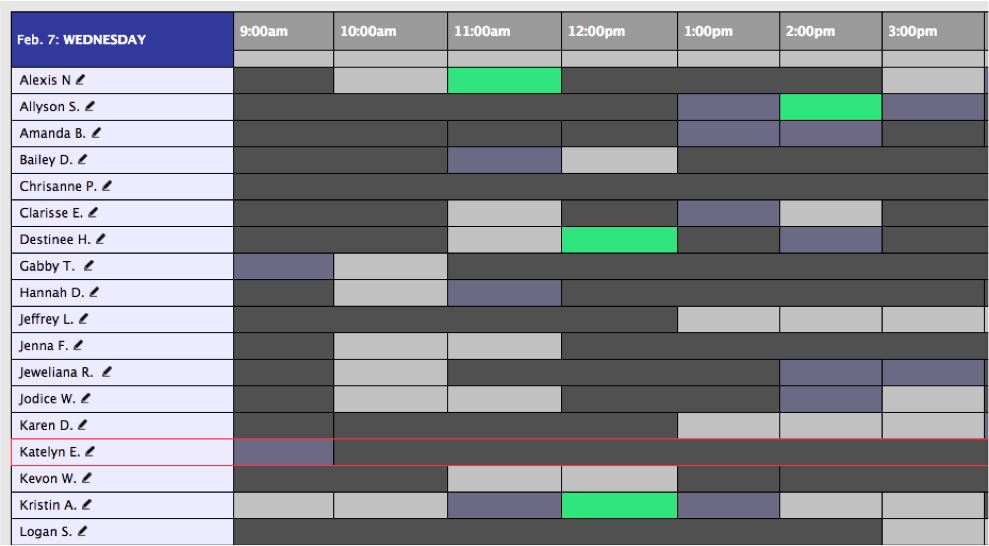

Each consultant is provided time during their weekly hours to complete modules; these hours are typically at the start of the semester. Through our scheduling system, WCOnline, we designated times that correlated with consultants’ current center hours to work through each module and put placeholders in for those hours. Figure 1 below shows an example of our center’s schedule.

Figure 1. Display of WCOnline schedule with green placeholders, which are used to designate time for module completion.

A green box indicates that a placeholder is occupying an hour of a consultant’s scheduled work hours. For example, we put a placeholder in for Destinee’s noon hour. On the appointment form, we noted that she should take the time to “complete Module 3.” As a result, instead of being available to assist students from noon to 1 P.M., Destinee used the allotted time to work through Module 3.

We recognize that each hour a consultant works is an hour that can be spent working one-on-one with a student, but we also recognize how ongoing professional development has been critical to our center’s growth and success. Therefore, we believe it is beneficial to have consultants go through these professional development opportunities while “on the clock,” especially during weeks of the semester that are slower, such as the first week of the semester or the week after midterms.

Module Overview

For each module, we created presentations, readings, quizzes, and discussion boards. To help the consultants navigate through the module with ease, we generated a list of “Instructions” and situated them at the top of each module. The “Instructions” label the slideshow, further reading(s), quiz, and discussion board numerically, alongside a brief sentence for additional guidance. Click here for an overview of how consultants navigate through the modules.

Instructions

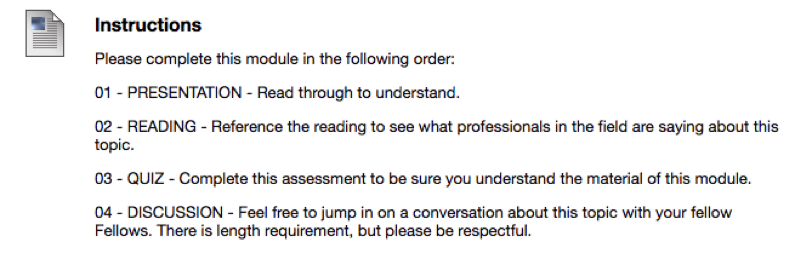

The instructions provide consultants with brief directions for how to complete each module, including the order in which to complete it. Figure 2 is an example of the instructions that were included with Module 1.

Figure 2. Image of instructions as shown in Module 1. This figure displays how the instructions are laid out in modules.

Presentation

The presentation that accompanies each module depends on the topic being covered. For example, Module 2 includes a presentation that discusses the basics of being an NSU writing consultant or writing fellow and offers strategies and advice they can implement in their sessions. These presentations are a large part of the modules, providing the majority of the information we hope staff will retain and practice.

Reading

Following each presentation is one or two readings relevant to the information covered in the module. For example, Module 6, which discusses strategies and techniques consultants can utilize when conducting sessions, asks consultants to read an excerpt “What Tutoring Is: Models and Strategies” from Tutoring Writing: A Practical Guide for Conferences by Donald A. McAndrew and Thomas J. Reigstad. These readings are supplementary to the presentation and ground the knowledge we put forth in writing center scholarship.

Quiz

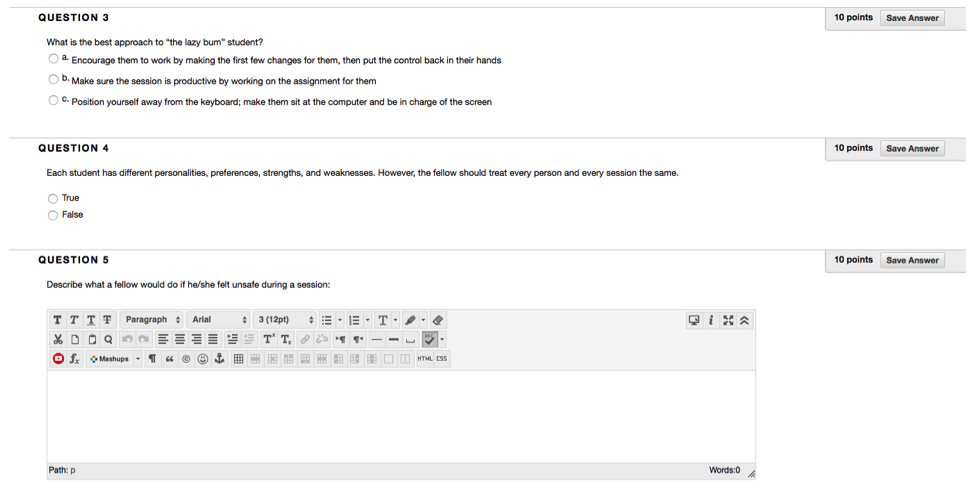

After consultants review the presentation and reading(s), they are asked to complete a quiz that tests their understanding of the content of each module. The quizzes consist of multiple choice, true or false, and open-ended questions. The quiz connected to Module 6 is located in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Question formats in Module 6 quiz. This figure illustrates the types of questions consultants are asked when completing quizzes.

Because Module 6 focuses on Studio Session Strategies, consultants are asked questions relating to how they can and/or should respond in different situations, such as an unsafe session, and to students with different personalities, such as “the lazy bum.” The questions challenge consultants’ understanding of the content they reviewed to help develop their skills.

Discussion Board

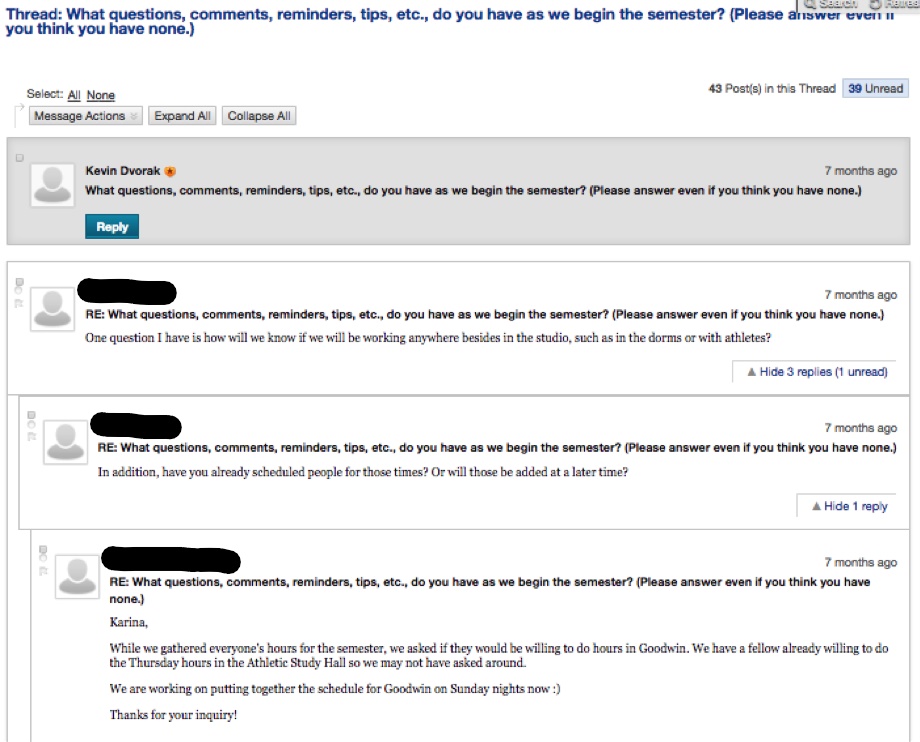

Lastly, students are guided to a discussion board. The discussion board provides each consultant with a “voice”; it offers them a platform to comment on the material, ask questions, present concerns, and offer feedback. It allows for deeper interaction between consultants and leadership. An example of the discussion board from Module 1 can be seen in Figure 4, which focuses on the structure and culture of the NSU WCC.

Figure 4. Module 1 discussion board. This figure displays how conversation occurs between staff members in discussion boards.

Consultants were asked “What questions, comments, reminders, tips, etc. do you have as we begin the semester?” Jenna initiated the discussion with a question, giving Karina the opportunity to build off of that question. Emalee, a Graduate Assistant Coordinator, then responded to the consultants questions via the discussion post.

Assessment

Recognizing the importance of research and assessment as integral to writing center training and development (Babcock and Thonus, 2012; Thompson and Mackiewicz, 2014; Schendel and Macauley, 2012), we knew we needed to assess the modules to determine their effectiveness. Midway through the fall semester, we created a formative assessment, which we called “Module Progress Assessment” (MPA), using the Google Forms platform. The survey sought to determine whether our writing consultants believed the modules were a suitable complement for the two-day, pre-semester training held in August. The MPA was distributed to 30 of our consultants; we received 28 responses. The MPA consisted of 6 questions intended to assess the four modules which had been opened for completion thus far.

Survey Questions

The survey consisted of the following six questions:

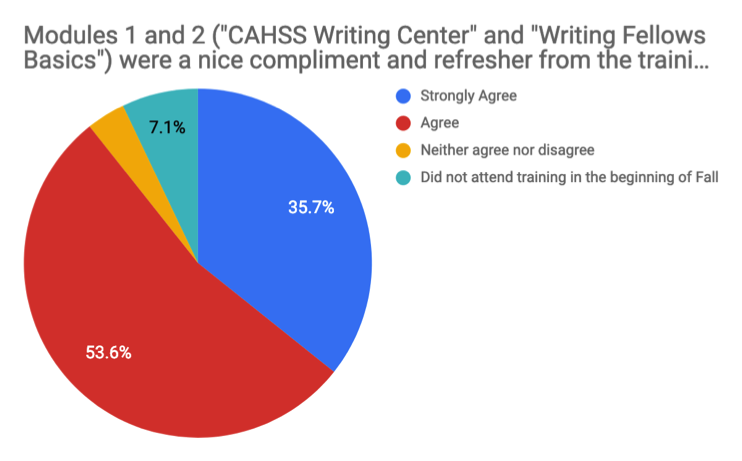

1. Modules 1 and 2 (“CAHSS Writing Center” and “Writing Fellow Basics”) were a nice complement and refresher from the training done in the beginning of Fall.

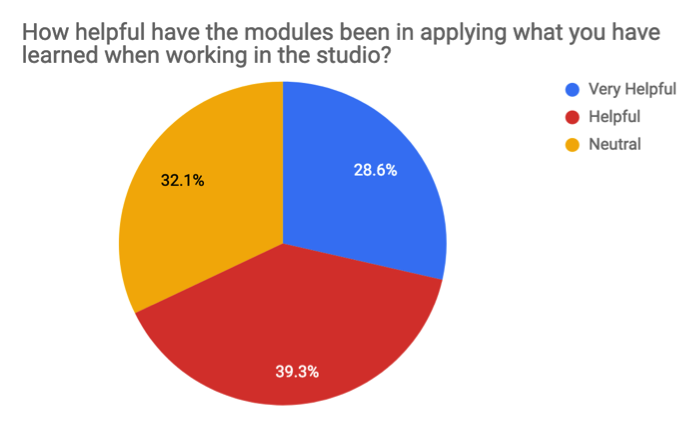

2. How helpful have the modules been in applying what you have learned when working in the studio?

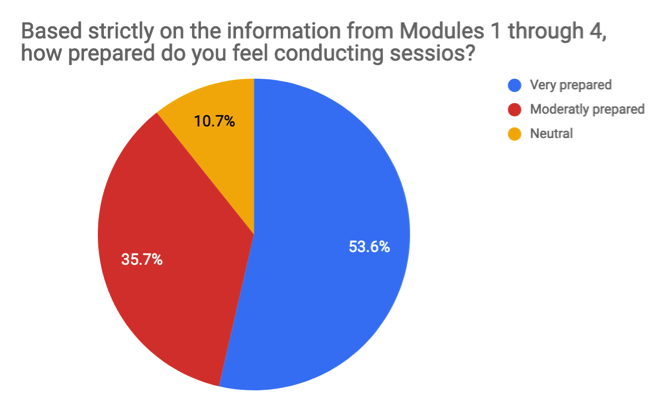

3. Based strictly on the information from Modules 1 through 4, how prepared do you feel conducting sessions?

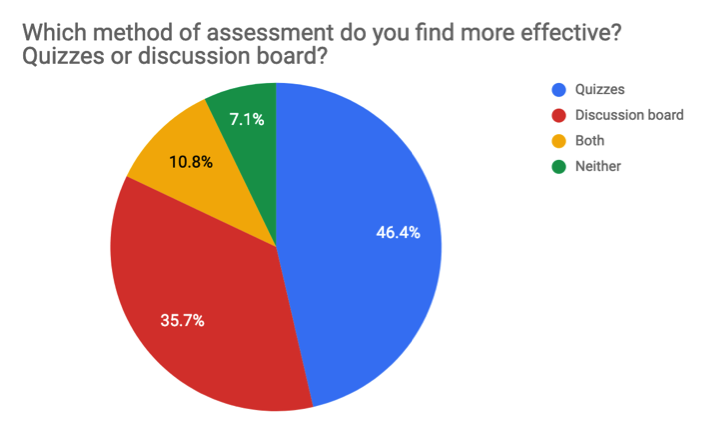

4. Which method of assessment do you find more effective? Quizzes or discussion board?

5. What would you like to have learned by now that you have not?

6. Do you have any suggestions for improvement?

Survey Results

Question 1

Figure 5. Survey Question 1. Not pictured: the 0% of respondents that answered “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree”.

To ensure that all of our writing consultants were on the same page regarding the culture, purpose, and methods of our WCC, we went over material including the software programs we use, WCC language, and other such details during our pre-semester training sessions. Since the modules remain available in Blackboard, our writing consultants are able to refer to them throughout the semester as needed.

It was especially important for us that these modules were easy to comprehend, navigate and access. As such, it was vitally important to know that 89.3% of our writing consultants agreed on some level that the first two modules were helpful. The 10.7% of respondents who either did not attend the pre-semester training sessions or consultants who were returning to the program and felt as those they were already well-informed regarding the basic practices of the WCC.

Question 2

Figure 6. Survey Question 2. Not pictured, the 0% of respondents that answered “Less helpful” and “Not at all helpful.”

Question 2 determined how the writing consultants felt about the training modules they had already utilized. We found that 28.6% of consultants felt as though the modules were “very helpful,” 39.3% believed that the modules were “helpful” and 32.1% remained neutral. None of the respondents indicated that they believed the modules were “less helpful” or “not at all helpful.” Therefore, we have determined that the modules have had positive effect on our consultants’ supplemental learning.

Question 3

Figure 7. Survey Question 3. Not pictured, the 0% of respondents that answered “Less prepared” and “Not at all prepared.”

We also wanted to know if modules one through four were enabling our consultants to feel confident about conducting sessions. Given the results of the assessment, we gather that 89.3% of consultants felt like the modules adequately prepared them, while 10.7% were indifferent. We believe the 10.7% can be accounted to the same group of consultants who were returning and felt as though they were already prepared given their previous experiences of conducting sessions. Overall, this was a positive outcome which showed that the modules were having the desired effect on our consultants regarding training.

Question 4

Figure 8. Survey Question 4.

Knowing we would be creating additional modules, we wanted to know which method of assessment the consultants preferred. We learned that 46.4% preferred quizzes, 35.7% preferred discussion boards, 10.8% liked both equally, and 7.1% disliked both methods. These answers have allowed us to have more concrete evidence as to why future modules may feature more quizzes than discussion boards.

Question 5

Question 5 was posed in a long essay format which allowed our consultants to relay what they wished they would have learned from the current modules. Popular responses included requests for more information regarding specific tutoring strategies for working with ESL students and clients who were unmotivated or reluctant to get involved in sessions. Consultants also requested more information about specific techniques which could be employed during class visits. Additionally, consultants mentioned that they wished to learn more about in-house related concerns such as standard WCC email protocol and Slack messaging.

Question 6

In Question 6, we wanted to know if consultants had any suggestions for improvement. We learned that consultants, in line with the requests mentioned in Question 5, wished to learn more about leadership roles and their colleagues. Again, consultants asked for information regarding how they might work with clients who had different personality types, suggestions for ways to react when professors weren’t utilizing them very much during class visits as course-embedded fellows, and for more tips from peer consultants. Consultants also wanted the modules to be accessible earlier in the semester.

Overall

As a result of our findings, we have decided to add additional modules that address specific topics raised by our consultants, such as those pertaining to working with various student populations. We also determined that the discussion boards were effective for having ongoing conversations online, but that they were not necessary for each module. Rather, we are going to create one centralized discussion board and have threads pertaining to each module. That will also allow consultants to create their own threads. Additionally, we will open the modules prior to the semester beginning so consultants can start preparing for their work prior to the pre-semester meetings if they want. Overall, the modules have helped us achieve our goals of educating and supporting a large staff of consultants while efficiently tracking their individual progress throughout the training process.

Discussion

In an effort to meet the demands of educating and training a large, diverse staff of writing consultants, the WCC implemented a series of online modules that staff members could access and complete during their work hours. These modules did not replace in-person staff training, but complemented an existing model; it also allowed for staff members hired during the semester (i.e., after summer training) to learn quickly how to work with student writers. As stated, these methods for educating and training staff members represent best practices from the fields of writing centers and writing studies, but they also are based on the local context in which they occur: a center that does not have a required training class, a center that hires new staff members at any time during the year, and a center that offers consultations at a variety of locations and online.

Our experiences with the modules, as well as the results of our early surveys and anecdotes from consultants, suggest that the modules have been effective in preparing staff for the work we do. We believe other centers can develop similar modules, employing strategies and technologies that best suit their institutional contexts. In fact, after presenting these modules at conferences, we have learned that some others centers have started similar initiatives.

We are excited about continuing to revise the online modules each semester in response to consultant feedback and the ever-changing needs of student writers. We recognize this as another evolution in the education and training of consultants and are interested in working with other centers who might offer similar opportunities. In the end, we offer the following recommendations for those interested in developing this type of (ongoing) staff education and training:

● Create appropriate learning outcomes: these are essentially your end goals; by developing them first, you know where you need to get to.

● Align outcomes and training to your institution’s core values/mission: it is important to support the institution; see Schendel and Macauley (2012) for more on this.

● Get feedback from the staff using the new training to shape future growth of the process and materials. This helps them practice peer reviewing, as well.

● Include peer consultants in the development of training materials. Asking consultants to contribute their own education and training materials allowed them to further engage with scholarship from the field. In our case, some staff members showed greater buy-in to the program and to the writing center community.

● Keep materials accessible and easy to alter (i.e. Google Docs). Instead of housing materials, such as a PowerPoint presentation, in a learning management system (LMS), such as Blackboard, create and maintain the presentation in a platform, such as Google SlideShow, that you can edit. Provide a link to the SlideShow in the LMS. If you house the presentation in the LMS, you will likely have to remove and re-upload each time you revise (which, for us, is often). Linking to a Google Doc set to “view only” allowed us to make changes that were implemented in real time.

References

Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. (2015). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Logan, UT: Utah State UP.

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center: Towards an evidence-based practice. New York: Peter Lang.

Barnett, R. W., & Blumner, J. S. (2007). The Longman guide to writing center theory and practice. New York: Pearson.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth, B. (Eds). (2009). ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann-Boynton/Cook.

Fitzgerald, L., & Ianetta, M. (2016). The Oxford guide for writing tutors: practice and research. New York, NY: Oxford UP.

Glover, C. (2006). “Kairos and the writing center: Modern perspectives on an ancient idea.” In C. Murphy & B. L. Stay (Eds.), The writing center director’s resource book (pp. 13-20). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McAndrew, D. A., & Reigstad, T. J. (2001). Tutoring writing: A practical guide for conferences. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann-Boynton/Cook.

NSU Newsroom. (2015). “Nova Southeastern University ranked among most diverse in the nation by U.S. News & World.” Retrieved on March 8, 2019 from Reporthttps://nsunews.nova.edu/nova-southeastern-university-ranked-among-most-diverse-in-the-nation-by-u-s-news-world-report/

Ryan, L., & Zimmerelli, L. (2010). The Bedford guide for writing tutors. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Schendel, E., & Macauley, W. J. (2012). Building writing center assessments that matter. Logan, UT: Utah State UP.

Soven, M. I. (2005). What every writing tutor needs to know. Cengage Learning. Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Thompson, I. K., & Mackiewicz, J. (2014). Talk about writing: The tutoring strategies of experienced writing center tutors. New York: Routledge