Madison Hansen and Nicole Carrobis, Boise State University

“The person who is most powerful has the privilege of denying their body”

~bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress

Introduction to Fatness and The Authors

When we first heard about the idea of a writing center dress code in the original call for proposals, we exchanged worried, knowing glances: a dress code would only make things more difficult for us. As fat working-class women in our early twenties engaging with writing center administration and teaching at the university level for the first time, our ability to perform professionalism through our dress was–and still is–complicated by how this particular embodiment of intersecting identities butts up against academic expectations. We’re prohibited from attaining academic professionalism: our age doesn’t lend us authority, our class doesn’t allow us to often purchase professional clothing (particularly at plus-size prices), and even with access to professional dress, our fat bodies would still be perceived differently.

Even though neither of us currently works in a writing center, we both still work in higher education and feel a vested interest in this article–both because we continue to care deeply about the work that writing centers do and because we are both now observing and experiencing fatphobia from new vantage points in the academy. When at work and out in our communities, we continue to only receive negative messages about our appearances and body size. To combat this hostility, we both engage frequently with fat positive Instagram accounts, which are usually neither professional nor academic. We hope to bring what we love about fat Instagram, the bits of representation, joy, and hope that we consume daily, into this piece where we will challenge what is academically and professionally appropriate. Drawing from the rhetorical benefits of Instagram is one such way we will challenge academic appropriateness.

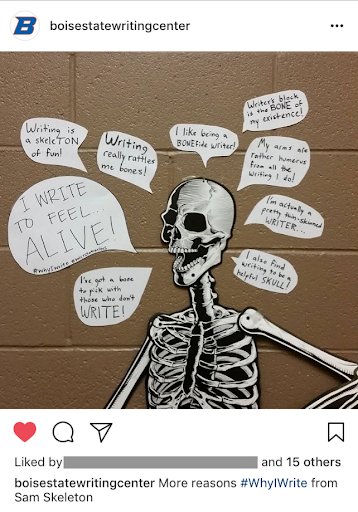

The writing center we worked at has an Instagram account, and this photo represents a pretty typical post. It’s created for a student audience, has some seasonal cheer, and plenty of puns are included. Attempting to make the writing center space more comfortable and casual by marking it with decorations that signify it’s a non-classroom space has long been a strategy to help put student writers at ease. In Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers, Jackie Grutsch McKinney challenges the grand narratives that writing centers are “cozy homes”, pointing out that notions of home are “culturally marked” (25) and laced with power, and that a comfy couch and coffee pot will likely do very little to ease writer’s anxiety and discomfort. But is instating a dress code to professionalize the space the appropriate response to this problematic grand narrative? We argue that it isn’t. And providing a baseline level of comfort is necessary to facilitate the work that happens in writing centers. Consultants should be able to fit–physically and culturally–into whatever they wear to work, and everyone who enters the space should be able to move through it and comfortably utilize the furniture. More about that later.

The writing center we worked at has an Instagram account, and this photo represents a pretty typical post. It’s created for a student audience, has some seasonal cheer, and plenty of puns are included. Attempting to make the writing center space more comfortable and casual by marking it with decorations that signify it’s a non-classroom space has long been a strategy to help put student writers at ease. In Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers, Jackie Grutsch McKinney challenges the grand narratives that writing centers are “cozy homes”, pointing out that notions of home are “culturally marked” (25) and laced with power, and that a comfy couch and coffee pot will likely do very little to ease writer’s anxiety and discomfort. But is instating a dress code to professionalize the space the appropriate response to this problematic grand narrative? We argue that it isn’t. And providing a baseline level of comfort is necessary to facilitate the work that happens in writing centers. Consultants should be able to fit–physically and culturally–into whatever they wear to work, and everyone who enters the space should be able to move through it and comfortably utilize the furniture. More about that later.

In order to justify our aversion to a writing center dress code, we further describe our personal experiences and theorize them through the lenses of embodiment and panoptic self-disciplining. A central goal of this piece is to “make room” (Smith) for fat studies in our field. Specifically, we discuss how dress codes impact consultants, students, administrators, and space at the intersection of size and other embodied identities. We argue that writing centers should refrain from enforcing guidelines for professional/peer dress, as such guidelines are coded in ways that reify the privileged position of thin, white, middle-class, and male-identified/traditionally masculine-expressing bodies. We conclude with guidelines for what administrators can do instead: focus on cultivating a culture where consultants get to discuss the tricky lines between being a peer and professional, trust that consultants will make effective dress choices based on those discussions, and then handle any issues that arise on a case-by-case basis and with an intersectional lens.

Performing Within and Against Fatness

Eric Steven Smith’s “Making Room for Fat Studies in Writing Center Theory and Practice” is–until now–the only source that theorizes the fields of fat studies and writing center studies together. Fat studies is “an interdisciplinary field of scholarship marked by an aggressive, consistent, rigorous critique of the negative assumptions, stereotypes, and stigma placed on fat and the fat body” (Solovay and Rothblum qtd. in Smith 17). Smith argues that body size and fatness constitute categories of difference, and that “like other minorities, fat bodies are in opposition to the traditional academic persona.” Unlike some other categories of difference, however, discrimination based on body size is often justified under the “social assumption [that] fat people themselves are culpable for their fatness” because of the stigmas that fat people lack “discipline, self-respect, and morality” (Farell qtd. in Smith 21). Since student writers and consultants with a variety of body shapes and sizes will inevitably appear in writing centers, it’s crucial for consultants to have some sort of training about body stigma and how to deal with it (Smith 21). Analyzing how body size interacts with other categories of privilege and oppression and how these categories are inscribed on the body is crucial for understanding the potential issues with mandating a dress code in the writing center.

Gender is one such category that is necessary to consider alongside fatness. To describe where gender comes from, philosopher and queer theorist Judith Butler writes:

…acts, gestures, and desire produce the effect of an internal core or substance, but produce this on the surface of the body…[these] are performative in the sense the the essence or identity that they otherwise purport to express are fabrications manufactured and sustained through corporeal signs and other discursive means. (185)

In other words: gender is not somehow inherently rooted in the soul or even biologically determined in the body; rather, gender is a series of acts–performances–that are displayed by and on one’s body and interpreted by others.

We find it important to distinguish between intentional performances of gender and unintentional performances of gender and other identities. For example: Madison identifies as queer and femme and her preferred wardrobe includes bright prints–which make her 5’11, size 26 body even harder to miss–and quite often makeup, which she considers to be an anxiety-reducing art form. Nicole, on the other hand, also identifies as queer considers her style to be more androgynous or masculine; because of her discomfort with tighter-fitting almost-always-pink clothes, she opted to wear men’s clothing into adulthood. These are intentional performative choices that align with our sense of self, and we make these choices knowing that others will observe, read, and make assumptions about us.

While we benefit from our years of experiencing learning to conceal our class and our whiteness is always a safety net to fall back on when our performances quite literally stretch the limits of the the acceptable academic body, there are still performances at the intersection of our fatness and gender that we are not in control of. We know that the body is a text, and readers of our fat gendered bodies in negative ways. Madison is read as excessive, hyper-feminine, and sexualized; Nicole is read as frumpy, plain, and stye-less. And we know that the ways we are perceived have consequences. Research shows that conventionally attractive professors who “dress in formal or stylish attire are…likely to receive better evaluations” (Escalera 205). This stigma threat can “endanger the professional safety and freedom” of fat academics and even “interfere with the learning process itself” (Escalera 210).

As graduate assistants in both the classroom and the writing center, it was explained to us that there was no dress code but that we needed to exercise ‘common sense’ and remain ‘appropriate.’ While we know that there were no ill intentions embedded in these loose guidelines, they did present a challenge for us because of the stigma threat described above. We knew from our many years of lived experience as fat women that how we presented ourselves could impact our relationships with faculty, peers, and our students. Educators–including not just professors, but writing center consultants and administrators–who have marginalized identities can decide, when they are able and willing, to perform parts of their identities differently in order to face less hostility from their colleagues and students.

Even if we had wanted to do this, our class, age, and size prevented us from doing so. Professional plus size clothing is incredibly expensive, limited, and difficult to find. Because we were so close in age to the students we served, we knew that wearing a blazer or nicer pants wouldn’t do much to change whether or not they’d respect us. And those professional clothes are always read differently on fat bodies anyways.

In our current positions, we both attempt to dress in ways that are professional enough to not raise concerns while also honoring our bodies, comfort, identities, and personal tastes–and we have the privilege of doing so because of an increase in income and understanding colleagues. Even still, our differing gender presentations reveal the complicated ways that fat women are pressured to look and behave in particular ways. Both physically and metaphorically, “fat women are…the antithesis of what it means to be appropriately feminine” (Giovanelli and Ostertag 290). There shouldn’t be excess on the academic woman’s body–not too much size, too much weight, too much gender, or too many markers of class; instead, everything streamlined and efficient and neatly in its place.

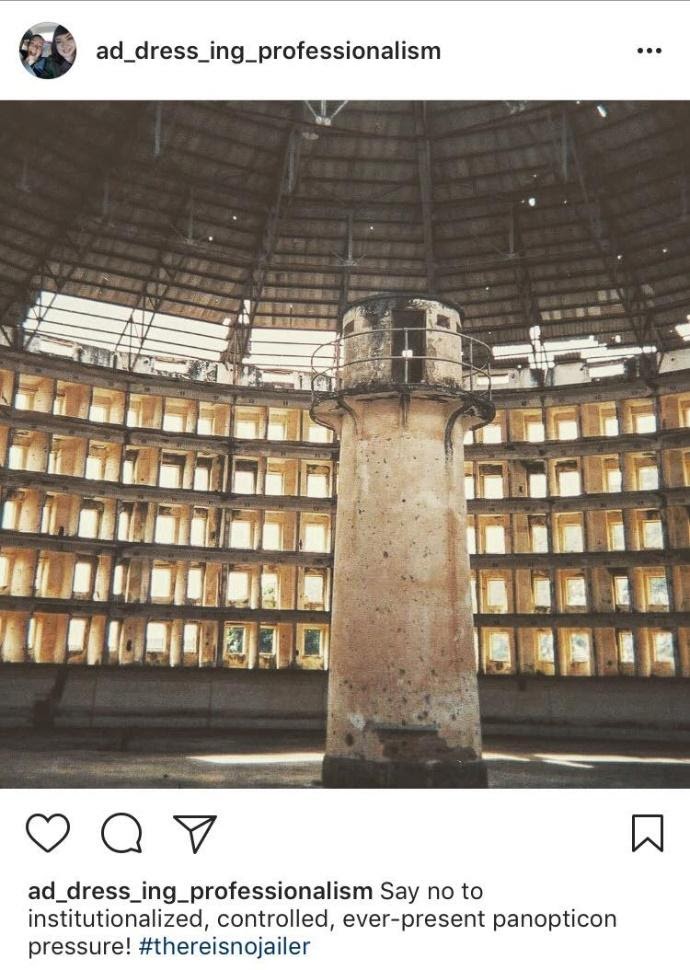

Fatness in the Higher Ed Panopticon

This ideal of aesthetic of the not-too-much academic woman is enforced both by outside pressures and by individual people eventually being forced to apply and succumb to this pressure to themselves. Foucault theorized this self-disciplining through Bentham’s panopticon, a form of prison with a single guard tower at the center and prisoners isolated from each other at the periphery. The prisoner at the margin “is seen, but…does not see,” and for the guard, the representative of power, his “invisibility is a guarantee of order…assur[ing] the automatic functioning of power” (Foucault 200-201). Surveillance of this kind is permanent: even when the subject is not being observed, the threat of surveillance forces her to disciplining herself according to the standards of power.

Several scholars have discussed panopticism in the context of fat studies. For example, Hetrick and Attig note that fat students, in their own surveillance, subject themselves to physical pain in small, rigid classroom desks in order to–culturally and physically–“fit in:…the hard materials and unforgiving shapes of these desks punish student bodies that exceed their boundaries with pain and social shame…Fat students’ bodies quite literally overflow the molds of academia” (199). Through this “corporeal pain” and emotional shame, the disciplinary tactics and rules of the university are “inscribed not only on the bodies of students, but also on their minds” (200). In this way, the institution doesn’t have to do any work to control the body of the fat student. The control has been transferred to the student’s body, and this panoptic force ensures that “The gaze is thus used as a disciplinary tactic… one that operates most successfully when enforced by students on their own and other bodies” (200).

Both of us exercised this gaze and pressure on ourselves while in the writing center. Even though the panoptic pressure did not result in us altering our performance of identity, we still felt constantly judged and self-conscious about the ways we were perceived and didn’t fit–physically and socially–in the writing center. This often showed up in our interactions with colleagues and student writers. For example, a popular topic for an undergraduate research paper is the “obesity epidemic,” often written about in terms of how working class children are neglected by their parents or how thin Americans will have to foot the bill for fat patients (both arguments which are tackled in the excellent Fat Studies Reader, by the way). Both of us encountered many of these papers in the writing center. As we heard the arguments read out loud, our fatness began to feel more exposed, more shameful; knots twisted in the pits of our stomachs. We most often did not have the courage to help the writer consider how their readers might take the tone of the argument, or the objective fact that many fat people live healthy happy lives, or our argument that fat people are deserving of respect and dignity, not condescension and hostility, regardless of their health status.

It was not until later in our careers at the writing center that we developed the confidence and authority within our fat bodies instead speak up about these things, calmly and compassionately. We acknowledge that the ability to even make this choice to mostly disregard panoptic pressure was a privilege we enjoyed in a writing center that felt very safe for us, and we believe the only way to foster or maintain this safeness for consultants and administrators is to shy away from dress codes. The conditions under which consultants are comfortable helping a writer consider another point of view in order to strengthen their writing, particularly when a consultants’ own identity, visible to the student, is implicated, are the same conditions which make a dress code unnecessary. Let’s unpack this idea through the lens of rhetorical embodiment.

Rhetorically Embodying Fatness and Identity

Just as writers who visit the center could be judged for not performing the rhetorical moves of academic discourse, professional dress sends a discursive message about participation in the academy. As panoptic power is dispensed “around the abnormal individual, to brand him and to alter him” (Foucault, Discipline and Punish 1999), the subject may have a more limited rhetorical range. While we’ve looked at how these forces press against and inscribe our bodies, it’s also important to look from the inside out: how subjects embody their positions of difference; how the corporeal form interacts with power and contains the subject. Knoblauch defines embodied knowledge as the “sense of knowing something through the body,” and embodied rhetoric as “a purposeful decision to include embodied knowledge and social positionalities of forms of meaning making” (52). While both embodied knowledge and embodied rhetoric aren’t typically accepted in academia, embodied rhetoric can provide a way of “reconnect[ing] our thinking with our particular bodies, understanding that knowledge comes from the body” (60).

Placed in Butler’s theory of performativity, this “understanding that knowledge comes from the body” would mean that knowledge is acted upon and internalized in the body, creating the effect that it’s an intrinsic truth being project outwards. Embodied rhetoric becomes a way of more intentionally and radically performing expressions that go against the expectations placed on particular kinds of bodies. The relationship between embodiment and performativity is complicated: we reflect all of the forces that are pressed on us, none of them natural or inherently “who we are,” but they’re inscribed on our physical forms nonetheless. The fact that identities and power are constructed and not inherent, though, “does not dismiss the very real lived experiences of [the] flesh, of people” (Knoblauch 60). Those real lived experiences manifest differently depending on the various subject positions, such as race, gender, class, ability, and size, that a person occupies simultaneously. This is why we contend that dress codes are also manifestations of power that impacts different sorts of subjects in different bodies, which is problematic for marginalized writing center consultants.

Many rules for dressing that are considered “common sense” are not so easy to adopt for marginalized writing center consultants. One common rule in a dress code may be to “dress modestly.” In addition to being a rule that would almost certainly only apply to women’s bodies and femme folks, it creates an extra constraint for fat women, who often know that a piece of clothing that is considered appropriate on a thin woman would be read as inappropriate on a fat body. Another rule may be to “avoid controversial attire.” In practice, this might look like a consultant refraining from wearing a t-shirt with a political statement, while a Muslim consultant might wonder if this means she shouldn’t wear hijab, or how his expressions and language could be perceived. Another may be to look “business casual,” or, like we heard as students, like we “didn’t just roll out of bed.” This could be challenging for working class consultants who, like us when we worked in the writing center, simply had no way to locate and afford a wardrobe like this.

While we anticipate that some will argue that having a standard set of rules for appearance eliminates any guess work and creates an equalizing effect, we contend that a dress code or standard of professionalism is not an equalizer because the community of people who would adhere to such a standard are not operating from even or equitable terrain. The attempt to communicate professionalism through the intentional rhetorical performance of adopting a dress code is lost in translation amid the sea of rhetoric about bodies that we’re already swimming in. In this way, a dress code is a futile performative attempt at professionalism, a costume that shows up and is read differently on different bodies with their various overlapping embodied and performed identities because some bodies will always already be perceived as unprofessional, threatening, and/or unfit for academic spaces. In the writing center, this only serves to at once perpetuate and invisibilize the marginalization of consultants.

As Knoblauch points out, “positionality within the academy and…social positionality are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In fact, social positionality often affects standing within the academy, and standing within the academy often affects the ways in which one is ‘allowed’ or sanctioned to write” (61). Thus, the intersectional identity interactions that we experience outside the academy are carried inside it. As writing centers increasingly attend to issues of social justice, tutors could also “be trained to understand that inhabiting a fat body brings with it marginal points of view that could inform one’s acquisition of academia and academic discourse” (Smith 17). As consultants and administrators engage in this intersectional training about embodiment, difficult discussions of dress code concerns can arise more naturally. When individual concerns arise, they must be addressed situationally. Even a writing center with limited time for training can work to normalize conversations about identity and the diverse student populations who will visit the center, including fat issues, in the writing center space outside of formal trainings.

Our Big Fat Suggestions (for Administrators and Consultants)

In addition to normalizing this talk, administrators can take actions on a daily basis in lieu of instating a dress code. We believe two main types of scenarios could arise: an administrator taking issue with how the consultant is performing (for example, wearing a political shirt or dressing “promiscuously”), or a client taking issue with a consultant’s appearance (for example, wearing a headscarf or being a woman with hairy legs). In all of these examples, administrators should have individual conversations with consultants about considering the rhetorical effects of their dress and if it’s appropriate for the consultant to alter their dress for the writing center space. Some questions to ask: what’s considered professional in these particular spaces? How are the “unprofessional” dress choices the consultants made tied up with identities? Which choices are unavoidable, and which would the consultant be willing to sacrifice for work? It’s a balancing act: while it’s important to represent our writing centers professionally and build good relationships with clients, we don’t want to further discipline our marginalized consultants (who are likely already disciplining themselves).

This of course is a lot of work, and it might seem like the easier option to instate a dress code. While it can be tempting, both for people in positions of privilege or marginalization, to ignore difference or sweep it under the rug in efforts to equalize, this doesn’t work in the end. We and Knoblauch recognize “that to ignore the body privileges the white masculinist discourse as universal. Such ignoring, in effect, erases difference, subsuming all into a discourse that has traditionally been white, male, and privileged” (58). Such ignoring also ensures that centers of power do not have to reveal themselves, and that the privileged norm is maintained. At the same time, the individual marginalized subject must surveil herself. Ignoring difference, then, is the primary mechanism of the academic panopticon.

We believe that most consultants who would “violate” the professionalism of a dress code live in marginalized bodies, and that marginalized consultants have enough critical awareness of their own positionality that they likely won’t wear things that violate the rhetorical constraints that their bodies place on their ability to gain the ethos necessary for their work. Additionally, we believe that a consultant can “prove that she understands the conventions…working within them and intentionally challenging them” (Knoblauch 61). According to Knoblauch, “this is an ‘interruption’ that can unsettle the supposed mastery of a [rhetor] who can work within these conventions” (61). A dress code takes away the ability to exercise embodied rhetoric that both reaches for the kind of academic ethos that is more easily attained by certain people in certain bodies and that challenges the need for that ethos. Writing centers exist to help writers communicate what they want to express in a way that is most effective for them as individuals; this should also hold true for our writing center consultants who are navigating academia.

Conclusion: Final Fat Thoughts

Essentially: we argue to not further contribute to the control of our consultants’ bodies, as they are already often aware of that control and exercise it on themselves. If they are not aware, the writing center is a “fitting” space where these ideas can be explored. Additionally, there is a long tradition of writing centers positioning themselves against the grain of academic power. Just as administrators and consultants often must make intentional choices to perform the appropriate ethos for academic spaces, we in writing centers can also allow some space for intentional performative rhetoric that pushes against the norm.

Virgie Tovar, seen in the photo here, is our favorite fat activist and instagram phenomenon. She pushes against norms in her own spaces: Instagram, blogs, the trains of San Francisco, and academia. The blog post that she’s promoting here discusses how even the most simple, daily tasks done by a thin person can become the object of scrutiny and discrimination when done by a fat person; she also takes this a step further to explain that these tasks can be opportunities for radical justice, if we let them be. Our administrators and consultants do their best work when they are physically comfortable and free to be themselves. Instead of asking fat consultants to cram themselves into dress codes–that are usually made in opposition to fat bodies in order to conceal them–we simply propose that we let fat consultants show up to work in the writing center as they are: fat and brilliant.

References

Airborne, Max. (2009). Cover artwork. Fat Studies Reader. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Butler, Judith. (2007). Gender Trouble. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge.

Chair image, modified by Nicole Carrobis, retrieved at: https://pixabay.com/en/desk-chair-retro-office-2079929/

Escalera, Elena Andrea. (2009). Stigma threat and the fat professor: Reducing student prejudice in the classroom. In The Fat Studies Reader, EEsther Rothblum and Sondra Solovay, Eds. New York, NY: New York University Press, 205-212.

Foucault, Michel. (1995). Discipline and Punish. Alan Sheridan, Tans. New York, NY: Random House.

Giovanelli, Dina and Stephen Ostertag. “Controlling the Body: Media Representations, Body Size, and Self-Discipline.” The Fat Studies Reader, Edited by Esther Rothblum and Sondra Solovay, New York UP, 2009, 289-298.

Hetrick, Ashley and Derek Attig. (2009). Sitting pretty: Fat bodies, classroom desks, and academic excess. In The Fat Studies Reader, Esther Rothblum and Sondra Solovay, Eds. New York, NY: New York University Press, 197-204.

Knoblauch, A. Abby. (2012). Bodies of knowledge: Definitions, delineations, and implications of embodied writing in the academy. Composition Studies, 40(2), 50-65.

McKinney, Jackie Grutsch. (2013). Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Panopticon image, modified by Nicole Carrobis, retrieved at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Presidio-modelo2.JPG

Smith, Eric Steven. (2012). Making room for fat studies in writing center theory and practice. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 10(1), 17–23.

Tovar, Virgie. (2018). Take the cake: 7 regular activities that become radical when fat. Retrieved from: @virgietovar, 16 February 2018. Instagram.