Matt Drollette, Independent scholar

I find dress codes to be strange cultural artifacts. In educational settings, dress codes seem to enforce homogeneity, equality, and community. Dress codes may be implemented as a way to eliminate distractions, but they also work to reinforce dominant cultural values like modesty, conservatism, or humility. In many cases, with the example of private school uniforms being most relevant to the current discussion, dress codes can be used to signal economic and social privilege and may function as a means of exclusion, with the uniform providing a clear visual differentiation between distinct social classes. It is this function of dress codes, the point at which clothing is used to represent status, class, power, and access, that caused me a great deal of conflict when I was considering how a dress code could (or whether a dress code should) be implemented at the University of Wyoming Writing Center (UW-WC).

As a new Writing Center Director, my first major decisions were related to the “feel” of the UW-WC, and looking through the literature, I was met by similar advice from multiple sources. Various handbooks make claims such as “it is important to put [students] at ease” and that relationships between tutors and writers should be “comfortable” (Clark 36). In “An Ideal Writing Center,” Hadfield et al. argue, in part, that this this feeling can be accomplished by considering the design of the writing center space: “space and design decisions should result in a space where people enjoy spending time and where they are happy, productive, creative, and social” (170). Additionally, the ideal writing center should be “calm, non-threatening, and easily understood (Hadfield et al. 171). From The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors, we get that tutors should be “pleasant and courteous” and that “being flippant or sarcastic may put some writers off” (Ryan and Zimmerelli 1). Other resources might provide us with a laundry list of things that appear in writing centers, as is the case with Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta’s description of a writing center as “a room or rooms with people, tables, books, computers, and other resources that support writers and tutors in their work” (Oxford Guide 14).

Though these statements do not all deal with the particular aesthetics of writing centers, they share the common goal of helping us to understand how a writing center should feel. We are told that writing centers are meant to be warm; there may be art on the walls, a coffee pot in the corner, comfortable couches or chairs, round tables, and big windows. Writing centers should be inviting; tutors should greet every student who walks in, the furniture should be arranged as openly as possible, and there should be a friendly face at the reception desk. Our collective idea of a writing center, what it should look like and how it should function, is an ideal that many writing center administrators aspire to and one that few have the resources to fully achieve. In many ways, too, this ideal, this agreed-upon narrative that defines (however loosely) what a writing center should be, provides a bedrock, a foundation upon which writing center people can build to construct their writing center identities; however, to paraphrase Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s interrogation of the “Writing Center Grand Narrative,” when we make our writing centers “warm,” whose warmth are we concerned about? When we try to make our writing centers “inviting,” who responds to the invitation and who are we unintentionally excluding?

This article is not about the spaces we writing-center people occupy, however. Rather, this article is about the people who occupy, visit, interact with, and create our spaces. More specifically, this article is about how the clothing we wear (or permit to be worn) in our writing centers is as much a part of our spaces as the furniture, art, computers, desks, and coffee pots. The clothing that tutors and writers wear in the center is at once an indicator of their comfort or discomfort in these spaces as well as a measure of how well writing centers are collectively achieving their goal to support all writers of all abilities from every background. In short, are we encouraging those who enter our centers to be conscientious of their clothing, performing the costumed act of academe, or are we truly creating braver, safer spaces for all writers, spaces wherein writers can overcome some of their self-consciousness and focus on writing instead? These questions and the concerns behind them led me to eventually adopt the following dress code for the UW-WC:

The UW-WC does not ascribe to a specific dress code. In general, employees should maintain a neat and clean appearance, practice good hygiene, and wear clothing that appropriately prepares them for the Wyoming weather. Employees should strive not to cause un-due offence or disruption by their clothing choices.

As a note, no clothing item will be considered offensive or prohibited unless it is determined that the clothing item constitutes hate speech or otherwise works to target marginalized or vulnerable communities, including but not limited to clothing that promotes racism, sexism, anti-LGBTQ sentiments, xenophobia, ableism, or ageism.[1]

If we can see past my blatant use of the passive voice and my sickly-sweet administrative tone, we can see that my main focus in this “dress code” is not on reinforcing conservative cultural values. Rather, my intent is to move toward a policy that allows for diversity, access, and self-expression, a flexible policy that hopefully creates an environment that feels inclusive, a policy that accounts for the safety and comfort of marginalized populations.

Of course, my policy is not enough, by itself, to ensure that the UW-WC is perceived as being warm, welcoming, and inclusive. Although we all do our best to create these safe, non-judgmental spaces, we also know that writing centers are involved in a balancing act between authority and approachability. All spaces, academic or otherwise, rely on explicit or implicit norms that establish authority or ownership over those spaces. In the case of writing centers, insiderness and otherness is constructed in binaries: tutor/tutee, client/consultant, or even employee/director. To avoid uneven power dynamics, we often refer to what happens in the writing center as peer tutoring, collaborative learning, or “guide-on-the-side” teaching; however, despite our efforts to balance power and to provide a space wherein writers feel welcome and maintain agency over their work, we can never eliminate the subconscious processes that are constantly causing both writer and tutor to evaluate each other along those lines of status and power. If we add to this context issues of race, gender, and class, it becomes difficult for tutors to remain outside, objective readers and for writers to experience the peer-tutoring environment promised by many writing centers. While much writing center research has focused on power dynamics, especially where identity is concerned, less work has been done to establish how the clothing worn by tutors and writers affects these power dynamics. To address this lack of a comprehensive scholarly conversation about clothing in our discipline, I from multiple fields of inquiry, including Social Psychology, Sociology, and Education, beginning with a discussion of the phenomena of perception, attribution, impression, and categorization. With this approach, I hope to provide insight into the development of writing center clothing policies that encourage inclusion and that contribute to our goal of making writing centers welcoming, warm, and comfortable spaces, especially for those writers who are least likely to feel comfortable in the catered spaces we encounter in higher-education environments.

Perception, Attribution, Impression, and Categorization

To better understand how clothing affects the ways in which writers, tutors, and administrators interact with writing center spaces, it is important to understand the cognitive and sociological theories that describe human reactions to clothing in different social contexts. In a 1988 article, scholars Leslie Davis and Sharron Lennon describe the potential connections between theories of cognitive psychology and the study of clothing and human behavior. In their article, Davis and Lennon pull from four theoretical frameworks, “social perception theory, attribution theory, impression formation theory, and the process of categorization” (175) and justify how each theoretical approach might intersect with the study of clothing.

According to Davis and Lennon, “Social perception theory deals with the perceptual processes used to create a unified social world from a mass of changing complex information” (175). Using social perception theory to study human behavior related to clothing allows us to better understand that our perceptions are determined by a desire or need for social unity, which is itself affected by three major factors: “(1) perceiver variables, (2) object or target variables, and (3) situational variables” (175). Social perception theory, then, allows us to independently study a person’s perceptions in relation to an object or target within various social contexts.

Moving on from social perception theory, Davis and Lennon describe attribution theory as providing “models for how people try to find causes for the behavior of themselves and others” (176). Attribution theory seeks to describe the process wherein individuals seek to find justification for another’s or their own behavior. Research combining the study of clothing and attribution theory finds that, for instance, mismatched verbal communication and non-verbal communication (clothing, etc.) corresponded with perceptions related to mental health or stability (Davis and Lennon 176). Further, Davis and Lennon discuss a particular study which found “that people believed they had performed better on intelligence tests when wearing eyeglasses as compared to when they did not wear eyeglasses” (176). Attribution theory, then, allows us to look at situations wherein the clothing choices of tutors, writers, and writing center administrators have the potential to determine or skew our perceptions of others to the point where we misconstrue another person’s character (or our own ability) based on the clothing that we or they choose to wear.

Additionally, Davis and Lennon discuss how impression formation theory, or the processes by which “diverse bits of information about a person are integrated into a general impression,” relates to the study of clothing and human behavior (177). Through the lens of impression formation theory, we can see how multiple visual cues (including clothing) work together to define our impressions of a person. With the understanding that “an impression [is] a synthesized whole and [is] more than the sum of its parts” (177), we can better determine which visual cues affect the development of positive or negative impressions and how those visual cues work with and against one another.

Finally, Davis and Lennon touch on categorization, a cognitive process related to the above-mentioned theories. According to Davis and Lennon, categorization is the “perceiver’s grouping of objects into categories” to organize and reduce “the vast complexity of the stimulus world” (177). Important to the study of clothing and human behavior is the fact that categorization is the underlying process in stereotyping, a process wherein “individuals are categorized as being a member of a particular social group,” and characteristics that are arbitrarily assigned to that social group are also assigned to the individual (177). Categorization, then, is the common thread that ties the theories together: our social perceptions of a person, our willingness to attribute behaviors to that person based on visual cues, and the impressions we form of people by synthesizing diverse visual and non-visual stimuli, all hinge on our cognitive imperative to assign people to various predefined categories or to create new cognitive categories as we interact with people who don’t easily fit within our limited range of assumptions (or stereotypes).

Clothing, Race, and Socioeconomic Status

With these approaches to understanding clothing and human behavior in mind, we can now begin looking at how clothing choice and dress policies intersect with Race and SES in educational environments. In a 2011 study published in Psychology & Society, Lauren McDermott and Terry Pettijohn investigate “the combination of clothing fashion, race, and socioeconomic status (SES) on person perception” (64). Specifically, they analyze perceptual differences among their participants (168 young adults of various ethnic backgrounds, though predominantly Caucasian) who were presented with photos of both black and white models wearing grey sweatshirts sporting a range of expensive brand logos, inexpensive brand logos, and no brand logo (as a control) (66). Participants were asked to “rate the socio-economic status of the person in the photograph on a 9-point…scale (1 = Lower Class, 5 = Middle Class, 9 = Upper Class)” (67).

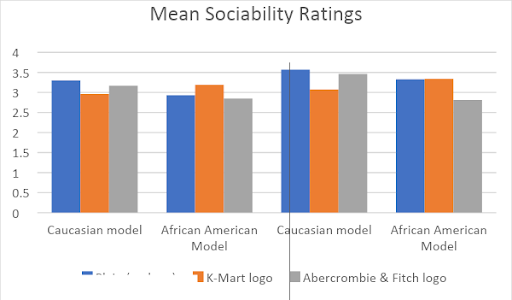

Participants were also asked to respond to statements based on how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement on a 5-point scale ranging from “1-Strongly Disagree” to “5-Strongly Agree”(67). The statements included “I think this person has a lot of friends,” “I think this person is successful in life,” “I think this person is attractive,” and “I think this person is intelligent” (67). With these questions, the researchers were able to determine not only whether students’ perceptions changed based on fashion, but how much the participants’ perceptions were influenced by race and SES. Although this study has some methodological limitations, including a predominately white participant pool and the inability to measure which specific stereotypes were either held or not held by participants, the results of their study help us to understand the ways in which racial stereotypes are connected to clothing. For instance, the authors note that “high SES dress…reduced beliefs about the African American model having lots of friends and participant’s [sic] desire to be friends with the model” (McDermott and Pettijohn 71). Conversely, the white model was rated as being more likely to have many friends when presented wearing more expensive clothing (see Figure 1).

With regard to my focus on clothing in writing centers, these findings are particularly disturbing, if unsurprising. If writing centers are committed to constructing spaces where socialization and collaboration can occur freely, what are the implications if our consultants are, consciously or otherwise, perceiving writers of color as less sociable simply because of a writer’s decision to wear a moderately expensive sweatshirt or similar high-SES clothing item? Further, how are our writing centers affected if writers are less likely to behave in a friendly way when working with tutors of color who are either dressed in high-SES clothing or who work in writing centers that impose a strict “professional” dress code? If our dress code relies on modern understandings of professional attire (button-down shirts, ties, skirts, slacks, etc.) than we run the risk of increasing and even reinforcing sub-conscious biases by limiting the ways in which our tutors can express themselves and by creating stark contrasts between writers and tutors, both of which can cause discomfort and contribute to an aesthetic of exclusivity, effectively creating in- and out-groups that undermine our intention to create welcoming spaces.

If our biases get in the way of effective tutoring and learning in a higher-ed environment, it’s important to understand that our perceptions of students (and of ourselves) have developed over our lifetimes. In fact, it may have been our teachers who helped us to reinforce negative stereotypes related to clothing and SES, making the process of avoiding negative perceptions that much more difficult. According to Caroline Fitzpatrick, Carolyn Côté-Lussier, and Clancy Blair, “if a student is well dressed, teachers may conclude that this student is also academically talented and kind…. In contrast, a disheveled student that is often late may be more likely to be perceived as less competent, talented and kind” (“Dressed and Groomed” 31). In their article “Dressed and Groomed for Success in Elementary School,” Fitzpatrick and her collogues examined the relationships among elementary school teachers’ perceptions of students’ appearance and “several domains of academic adjustment[,] including classroom engagement, academic self-concept and motivation, teacher-child relationship, and parent-teacher partnership” (32). In analyzing responses from fourth-grade teachers, and with a sample size of 1,311 students, Fitzpatrick et. al found that “a broad range of academic adjustment indicators were related to features of student appearance” and that “Students described by teachers as appearing poorly dressed, tired, sleepy, or hungry were rated by teachers as being less competent academically, less engaged, and as having a poorer relationship with [their] teachers” (37). Additionally, this study showed that perceptions related to appearance and associated academic adjustments were not explicitly connected to SES or material disadvantage (40), meaning that “appearance may be independently associated with performance in school” beyond the effects of SES (40). If a student’s attire has a measurable impact on academic success in grade school, it’s likely that this impact (negative or positive) is somehow related to the perceptions of teachers and classmates. And, if we synthesize these findings with those of the previous study, the outlook may be even more grim. Students of color, regardless of SES, may be perceived as less prepared, less academically competent, and less engaged, which perceptions have likely followed them from grade school. What’s more, these students are almost guaranteed to engender continued (and likely false) perceptions related to their ability, regardless of the clothing options available to them. If our dress codes are meant to help us maintain spaces of inclusivity, then we need dress codes that do not reinforce the notion that personal appearance is somehow tied to writers’ and tutors’ character. To state this explicitly: we need dress codes that reject the “dress for success” mentality.

Impressions and Perceptions of the Self

While it’s now clear that clothing impacts our perceptions of others, there’s also evidence to show that our self-perceptions are, in part, dictated by our clothing choices. Distinct from the other studies I’ve cited above, one study, titled “‘The Clothing Makes the Self’ Via Knowledge Activation,” measures self-perception and impression formation based on an individual’s attire. The researchers in this study, Bettina Hannover and Ulrich Kühnen, build from a wealth of studies in which participants are asked to assess their own perceptions of others’, which studies had some interesting conclusions. Pulling from Hannover and Kühnen’s literature review, we can see from one study that “students judged casually dressed teachers as more approachable, but less knowledgeable than formally dressed teachers” (2514). Additionally, Hannover and Kühnen cite one study that suggests similar findings in relation to teachers’ perceptions of students. Particularly, teachers ratings of students’ “intelligence, scholastic abilities, and academic potentials were more positive if the [student] models were dressed formally” (2514). Of this study, the researchers note that “such expectancies about students’ academic potentials might…guide teachers’ behavior… and ultimately result in biased evaluations of the students’ achievements” (2514). With these results in mind, Hannover and Kühnen turn participants’ perceptual gazes inward, asking them to perform impromptu self-evaluations while wearing either formal or casual clothing.

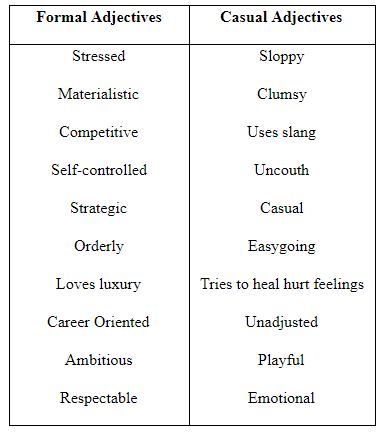

In their study, Hannover and Kühnen asked students to show up for the experiment wearing either formal or casual clothing and asked the students to respond either “me” or “not-me” when read a list of adjectives (See Table 1) that were earlier rated on a 1 to 5 scale based on the adjective’s level of formality. In line with the researcher’s predictions based on previous studies, although casual adjectives were given the “me” designation most often by all participants, those participants who were dressed formally were more likely to identify with formal adjectives than those participants who were dressed informally. If we look at that list of formal adjectives, we see both positive and negative traits, including “stressed” and “materialistic,” both traits that we would hope are not represented in our tutors and/or our clients. However, we also see positive traits, like “orderly” and “respectable” that may be advantageous characteristics for writing centers to embody. Contrasted with the casual adjectives, though, we see that positive traits associated with less formal clothing choices are much more in line with the grand narrative of the ideal writing center. Traits like “casual,” “easygoing,” and “tries to heal hurt feelings,” align themselves with the “Writing Center as Home” narrative, or the idea that a “homelike” environment in writing centers is linked to increased learning (Grutsch McKinney).

If, as Hannover and Kühnen’s research suggests, our tutors and clients perceive themselves differently (and, therefore, behave differently) depending on how formally or casually they are dressed, we can assume that best practices related to writing center dress codes should take into consideration the traits or adjectives that we want our writing centers to embody. Are we more interested in having orderly and ambitious centers with high stress, or should we foster centers that are casual, easygoing, and empathetic, but prone to sloppiness? Of course, although Hannover and Kühnen’s “formal/casual” binary does not allow for much interplay between the two categories, it may be possible to use dress-code policies to selectively foster positive traits from both categories. A dress code hoping for this outcome might choose to select uniforms that adhere to business-casual norms. A more flexible dress code could give tutors more options, foster positive traits from both the formal and informal adjective categories, and meet the broader objectives that a writing center might seek to meet with the implementation of a dress-code policy. Similarly, our policies might only include prohibitions on certain types of clothing. For example, many public secondary school dress codes prohibit clothing articles that are revealing, offensive, or related to criminal activity (drugs, gang affiliation, etc.).

While I think the idea of implementing flexible dress codes could successfully help writing centers balance positive traits from both the formal and informal categories listed previously, my position is that even the most flexible of dress codes could create divisions. For instance, while a writing center that increases its professional appearance with the implementation of a dress code could garner favor with administrators and diverse stakeholders, that same professionalization could create stark contrasts between tutors and the writers they work with, writers who, we can assume, will most often be dressed more casually than our tutors. This visual contrast, in effect, could erode the peer-tutor dynamic to which many writing centers aspire, particularly if clients perceive our tutors as less sociable, less approachable, or less intelligent, all impressions that could be reinforced by any given dress code.

Clothing as Free Speech

In addition to eroding the peer-tutoring dynamic of a writing center, mildly prohibitive dress codes could also put our centers in conflict with our institutions’ stated values or even limit our tutors’ constitutional rights to freedom of expression in the United Sates. As Margaret Weaver notes in her article “Censoring What Tutors’ Clothing ‘Says’: First Amendment Rights/Writes Within Tutorial Space,” “Numerous courts have emphasized this particular right [to freedom of expression in educational environments] time and time again: physical adornment is a form of symbolic speech” (20). In Weaver’s article, she describes a situation wherein a tutor wears a potentially offensive t-shirt to the writing center and her struggle to come to terms with the conflict between her center’s goal to be a welcoming “safe space” and the necessity for free expression at institutions of higher education. Particularly, Weaver notes that “free expression of competing views is essential to the institution’s educational mission” (22). With this function of American public colleges in mind, Weaver concludes, “Perhaps our mission should not be to provide a friendly and comfortable ‘safe house’ for students where tutors censor themselves but to provide a disruptive environment of dialogue that reflects our commitment to the First Amendment” (33). Here, Weaver’s position aligns itself with Grutsch McKinney’s conclusion to her chapter “Writing Centers are Cozy Homes,” wherein Grutsch McKinney interrogates common written descriptions of various writing centers. Of those descriptions, Grutsch McKinney states:

Although all [writing center] descriptions are shorthand, are in flux, are underdetermined and overdetermined, just as all writing centers are, we can work toward a narrative that allows for multiple interpretations, thick descriptions, and even dissonance. What we ought to stop doing is using descriptions to fortify a narrative of cozy homes simply because it allows us to imagine that our spaces are (or should be) friendly or that writing about our centers in particular ways marks us as belonging to the writing center culture. (34)

Though this passage is related to descriptions of writing center spaces, we can argue that clothing is a part of those spaces. In short, then, our desire to regulate what tutors, students, and administrators wear in the writing center could potentially disrupt a core tenant of higher education: open, competing dialogue that spurs academic and intellectual growth. Further, strictly regulated dress codes could reinforce the “cozy home” narrative, which narrative could impede the forms of self-expression that allow for the synthesis of competing ideas and the creation of new knowledge, both of which are essential to colleges, universities, and writing centers in the United States and abroad.

An Inconclusive Conclusion

At the conclusion of this essay, I wish to note that I am not a psychologist, a social scientist, nor an expert on human cognition. As my bio illustrates, I have a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing, a master’s degree in English, and an undergraduate minor in Family Studies. With that said, I do not claim the authority to dictate what other writing center administrators choose to do with regard to dress codes in their centers, but I hope that the research I have presented helps in that decision-making process. While there’s still much research that needs to take place to establish best practices for writing center dress code policies, we can use relevant research in other fields to guide our efforts. For instance, our understanding of how clothing functions as an unstable, contextual symbol should cause us to investigate our local contexts to ensure our clothing policies do not reinforce any negative socio-cultural assumptions that may be present at our institutions. We should ask ourselves, “Will mandating professional dress standards be positively or negatively perceived by those we serve?” Additionally, our awareness regarding how students of color are perceived differently than white students with regard to brand-name or expensive clothing should help us to write dress codes that promote diversity and social engagement. As we work with students, tutors, and administrators when developing these policies, we should be aware not only of how clothing affects others’ perceptions of us, but also how our polices could affect our tutors’ self-impressions, both negatively and positively. Finally, we who work at publicly-funded institutions should be careful that our policies do not unintentionally create environments wherein students and tutors feel that only “acceptable” forms of communication are permissible, spaces wherein active participation in knowledge construction is limited to those whose ideas are inoffensive.

Understandably, policies are, by their very nature, limiting, and my suggestions of how to use the presented research lean toward policies that are universally flexible, policies that increase diversity, policies that challenge societal norms, and policies that work to deconstruct damaging stereotypes. From this perspective, that all policies are intended to limit, define, and categorize based on pre-determined notions of the “acceptable,” might it be more effective for us to allow students and tutors to determine what is socially acceptable while we provide guidance and encouragement? Might allowing students to conform to or diverge from the norm provide for engaging debates and important learning opportunities? Perhaps, then, if our centers can be served best by avoiding strict clothing standards, it might be enough for me, as a writing center director, to make sure my tutors’ clothing gets them through a Wyoming winter. If they survive, there will be plenty of time to train my tutors to avoid the pitfalls created by the human tendency to categorize, stereotype, and construct negative (or positive) perceptions of ourselves and others based on something as arbitrary as the material we use to keep our bodies at a comfortable ninety-eight-point-six degrees Fahrenheit.

Notes

- The UW-WC Dress Policy is taken directly from our in-house consultant handbook. ↑

References

Beaudoin, Pierre and Marie J. Lachance. (2016). Determinants of adolescents’ brand sensitivity to clothing. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 34(4), 312-331.

Clark, Irene. (1992). Writing in the Center: Teaching in a Writing Center Setting. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Davis, Leslie L. (1988). Social cognition and the study of clothing and human behavior. Social Behavior and Personality, 16(2), 175-186.

Denny, Harry. (2005). Queering the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 25(2), 39-62.

Fitzgerald, Lauren and Melissa Ianetta. (2016). The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Fitzpatrick, Caroline, Carolyn Côté-Lussier, and Clancy Blair. (2016). Dressed and groomed for success in elementary school. The Elementary School Journal, 117(1), 30-46.

Hadfield, Leslie et al. (2003). An ideal writing center. In The Center Will Hold, Michael Pemberton and Joyce Kinkead, Eds. Logan, UT: Utah State University, pp. 166-176.

Hannover, Bettina and Ulrich Kühnen. (2002). ‘The clothing makes the self’ via knowledge activation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(12), 2513-2525.

McDermott, Lauren A and Terry F. Pettijohn II. “The Influence of Clothing Fashion and Race on the Perceived Socioeconomic Status and Person Perception of College Students.” Psychology and Society, vol. 4, no. 2, 2011, pp. 64-75.

Grutsch McKinney, Jackie. (2013). Peripheral Visions for Writing Centers. Logan, UT: Utah State University.

Rees, David W., Lynn Williams, and Howard Giles. (1974). Dress Style and Symbolic Meaning. International Journal of Symbology, 5(1), 1-8.

Ryan, Leigh and Lisa Zimmerelli. (2010). The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. Boston, MA: Bedford St. Martins.

Weaver, Margaret. (2004). Censoring what tutors’ clothing ‘says’: First amendment rights/writes within tutorial Space. The Writing Center Journal, 24(2), 19-36.