Leslie Anglesey

Maureen McBride

The history of writing center scholarship presents a nuanced understanding of what it means for our students to feel welcomed into writing center spaces. Much of this foundational work has explored the social and physical (and even digital and online) spaces of writing centers. However, welcome is a complex concept that requires a critical examination of our writing center ethos as well as our practices. While welcome has been explored in much writing center scholarship, little attention has been paid to the ways in which writing consultants’ practice of listening contributes to the feeling of welcome for students and to the center’s ethos.

Listening, as we will demonstrate, is not just the physical act of taking in and processing aural sounds and symbols, but is a stance of openness and engagement that an individual—including writing consultants—can assume in relation to another person or text (Ratcliffe, 2005). By defining listening in this way, we draw upon Heidegger’s notion of listening as the process of “laying-to-let-lie-before,” which Fiumara (1990) subsequently described as the safekeeping of the ideas of another, or a willingness to provide shelter, even if only temporarily, to the ideas of another (p.4). This form of listening is what we will call listening to shelter. By defining listening as the process of providing shelter to another person’s ideas, we seek to contrast this against the form of listening that is more commonly deployed in Western culture: listening to respond. Listening to respond is motivated by the listener’s need to engage in a conversational give-and-take, which renders the listener less interested in understanding (or, as Heidegger would say, “standing under”) their conversant’s ideas and more interested in listening for an entry point to continue, redirect, or combat the conversant’s ideas. By examining listening through the lenses of listening to shelter and listing to respond, this article seeks to add to scholarly discussions related to issues of welcome in the writing center by exploring the ways in which a basic component of writing center work—listening—can be reimagined as an essential function of a center’s ethos of welcome for all students.

The intersections of welcome and identity can provide insight into the complications that may arise when writing centers approach writing support from a predetermined context of “student” and of “writing support” (Blazer, 2015). We define welcome as a feature of writing center ethos that foregrounds the need for our spaces—physical, social, and institutional—to be inclusive to all students on campus. We recognize, however, that students’ sense of identity (the multiple, complex, and sometimes conflicting notions students have of who they think they are, as well as the perceived social, political, and interpersonal ramifications of those identities) can interfere with whether or not they feel welcomed and included among writing center users. For example, if a center is located on the basement level of a building with no ADA access, students with physical and/or mobility disabilities may not feel welcomed or included as users of that center. On a more nuanced level, we also see the social spaces of writer centers as potential locations of barriers that prevent students from feeling welcomed in the center. We see our consultants’ approaches to listening as part of the social fabric of our center. If a student with a speech impediment or a processing disorder comes to our centers and our consultants are not prepared to listen to such individuals with patience and care, we see this as creating access barriers to all students feeling welcomed and included in our center. In this respect, we follow Bokser (2005) in defining welcome as a sense of belonging.

We see the need to develop listening to shelter as one way in which our center can be more welcoming—more inclusive—of students with disabilities. The inclusion of disabilities studies into our discussion of listening is essential to creating the welcome we hope to achieve by addressing ableist perspectives that implicate the body in strategies often taught to writing consultants, such as body positioning and eye contact (Bokser, 2005). While writing center scholarship has long been committed to supporting diversity, only recently has it began focusing on the needs of students with disabilities (Babcock & Daniels, 2017). Students with disabilities are a historically marginalized group. We focus on this population, in particular, because, as writing studies and disability scholar Hitt (2017) notes, “some [of writing centers’] best practices are framed for students with particular abilities” (p. vii). Expanding our views of listening beyond ablest perspectives also addresses Elston’s (2015) call for writing center training to help writing consultants move beyond medical models of disability.

As a starting point to shift writing centers toward more inclusive and supportive methods of listening, Kiedaisch and Dinitz (2007) claim that training should start by looking at difference within the writing center instead of outside the center. They invite writing center directors and administrations to engage in inquiry into their local contexts, looking at the ways in which they can design their centers to respond to the needs of their users with individualized, rather than blanketed, approaches. Following Kiedaisch and Dinitz’s (2007) call for localized responses to design for inclusivity, we focus on the social environments of our writing center and see developing tutoring practices that include listening to shelter as an essential part of creating welcome. In this article we seek to understand how the social contexts of writing center work may limit the extent to which students with disabilities may feel welcome and included in our center. Specifically, we explore the ways in which a basic element of writing center work—listening—can be reimagined as a way of welcoming individuals with disability. By focusing on listening practices that are inclusive to all individuals, our goal is to transform our writing center space without having to make listening accommodations for individuals, thus helping us make our writing centers usable for all.

Writing Center Conversations about Listening & Disabilities

In writing center scholarship, the role of listening is imperative in the very nature of helping a student—if we are not listening, we may impose our agenda onto a writer and their text, falling into the trap of helping the student’s writing look more like ours rather than helping the student develop their writerly identity. Embedded within concepts of listening are opportunities to use empathy as part of our listening strategies. Ultimately, if students feel listened to in ways that are empathetic to their individuality as writers and learners, writing centers may be able to increase how students are welcomed into our centers and the positive impact of our support.

To understand how listening can be used to further our work in writing centers, we need to examine our current practices, including reflecting on our conceptions and perceptions of what listening is. Bokser’s (2005) research highlights how writing consultants’ affiliations and perceptions of performance expectations affect the ways in which they listen during writing center consultations, noting that writing consultants were able to actively listen when they positioned themselves in the role of learner within their consultations. She claims that writing consultants need to examine their listening practices so they can add to and adjust those practices. Bokser (2005) suggests that consultant training should focus on three types of listening: listening to self, listening to others, and listening to scholarship. Practically, this means reflecting on our experiences (e.g. analyzing a videotaped session), inviting feedback from students or consultants (e.g. being observed by another tutor or survey feedback from students), and reading and discussing current scholarship that is stretching the boundaries of our understanding (e.g. writing a summary of a seminal work).

We see Bokser’s work as foundational to situating listening as a complex, social act. Because she situates listening as dependent upon situation, we recognize a call for developing repertoires of listening habits that are responsive to audience, to situation, and to context. Put simply, we see a call to treat listening as kairotic. This call has been issued in more explicit terms by Ratcliffe (2005), whose work could be applied in writing center contexts. For example, we may benefit from examining how listening can be used to privilege positions of “whiteness” when writing center consultants choose not to listen or choose to listen only to respond. Applying Ratcliffe’s Rhetorical Listening (2005) to our writing center contexts, we may caution against too much identification on the part of the consultant that can lead to a lack of recognizing power differentials between consultants and students. Such problematic identifications also occur along lines of ability. Our able-bodied consultants may expect that, in the absence of any indications that a student writer is disabled, the student writer behave as able-bodied. But our listening practices are encoded with practices, habits, and behaviors that are informed by our intersectional identities, including our status as dis/abled (a point we return to in the discussion section).

Once we understand current conceptualizations of listening, the next step is to examine our practices and expand our definitions of what counts as listening. Babcock and Thonus (2012) also discuss the need for writing consultants to understand listening, to understand the role of silence, and to be aware of the balance of who is talking. The awareness of how talk and silence function is key to fully implementing the listening strategies that may create the welcome we hope to achieve in writing centers as well as to shift the ethos of our centers (Blazer, 2015). By moving beyond the body as the focus for listening, Santa (2016) suggests that writing consultants can listen for more information that will help them respond to students and create a sense of welcome, creating opportunities for listening to be more visible in writing center training and consultations. To achieve this, Stenberg (2011) suggests moving away from the metaphors of listening as a hunting or knowledge-seeking activity. Instead, Stenberg (2011) suggests that consultants focus on developing a habit of listening to respond and to support the student. The literature on listening in writing centers suggests that accessing more nuanced ways of listening and reasons to listen may allow writing consultants to move into more responsive and adaptable positions.

Part of the motivation to examine our listening practices is to create a more welcoming space for all students. Examining students who may not always feel “welcome” at our centers can help us to identify opportunities to expand our understanding and approaches to providing writing support. Students who may identify as disabled are a population that may help us better understand how to use approaches to create a greater scope of welcome for more students. So, we start with a question: To what extent do students, especially those who may identify as disabled (or be identified through various institutional mechanisms), feel welcomed into writing centers? This question echoes the calls from Babcock (2015), Rinaldi (2015) and from IWCA’s position statement (2006) to address the gaps where research between writing centers and disabilities studies intersect.

Writing center administrators and consultants may struggle to identify students with disabilities and to create a sense of welcome because they are uncertain how to address students with disabilities and their needs (Garbus, 2017; Jackson & Blythman, 2017) or because invisible disabilities make it seem as though the students who come to writing centers do not have access challenges (Elston, 2015). Only within the past few years have writing center scholars begun to earnestly inquire into the extent to which students with diverse disabilities feel welcome in our centers (Babcock, 2012; Babcock & Daniels, 2017; Mullin, 2002). Regardless of the reasons for its absence, scholars working at the intersections of writing centers and disability studies have now created a vibrant area of research committed to identifying the needs our students present and the opportunities they offer for making our writing centers more just and equitable for learning. Thus, we believe that creating an equitable and just writing center practice comes from developing a sense of welcome, belonging, and inclusivity by developing the habit of listening to shelter during writing consultations.

One way that disability scholars are invigorating writing center research is by looking beyond the basic question ‘what problem do students with disabilities present and how can we solve them,’ a question rooted in the assumption that students with disabilities are a hindrance to their own learning. A proposed different question is ‘how do writing center spaces, practices, theories, and pedagogies limit the ways in which students with diverse abilities can access this resource?’ These scholars operate on the assumption that it is the institutional contexts—not the students—that need examination and, potentially, corrective guidance.

To examine how our institutional context impacts our work, we may want to consider how our spaces and expectations impact a sense of welcome for students. When we enter many writing centers, one of the first things we may notice is the sound of talk between and among writing consultants, administrators, and student writers. We consider this to be one hallmark of an active writing center space. As many writing center scholars have observed, writing support should be a collaborative practice among knowledgeable peers often taking place as verbal discussion (Gellar, 2013; Lunsford, 1991). Much of the research about writing center collaboration, however, is premised on the assumption that listening in these moments is an accessible model of collaboration.

Daniels et al. (2015) claim that active listening is important to support students with disabilities. These researchers suggest that writing consultants should be trained to ask certain questions to identify goals and approaches students would like to use in writing consultations. To understand and effectively respond to students, writing consultants need to be trained in these adaptable approaches. Using the approach of active listening allows writing consultants to respond to non-physical or visually identifiable disabilities and does not require students to self-disclose disabilities; this approach also encourages writing consultants to refrain from informally ‘diagnosing’ students, a habit that we identified some of our consultants use. This ability to respond to individuals whose official diagnoses may not be available to writing consultants is an important step to make writing centers safe spaces for students with disabilities (Degner, Wojciehowski, and Giroux, 2015), providing them with an environment that supports their work on their writing and supports their choice to reveal any disabilities based on the relevance to their goals in the writing center.

Certainly, listening is only one aspect of addressing students’ concerns about their writing, but it is a central strategy used by writing centers. Becoming more analytical and intentional in our understanding of what listening encompasses, such as moving beyond a physical conception of listening, and how it can effectively be used to understand students’ concerns and provide them with guidance and support, may improve our ability to train consultants to respond to a broader range of students and create a stronger sense of welcome.

Our Project

In response to the literature, our project attempts to address the lack of scholarship regarding the role of listening in writing centers, especially regarding writing support for students with disabilities. To address this, we implemented a training intervention focused on listening awareness and awareness of disabilities studies. This article details an ongoing consultant training series we have initiated in our writing center to disrupt these assumptions based upon the insight that disability studies (DS) bears on writing center practice. These insights began, in part, through Leslie’s lived experiences as a writing center tutor, writing center user, and as a person who identifies as having a mental disability[1].

Our research shows that writing center directors, writing consultants, and academics take for granted that we know how to listen and rarely question what we should be listening for or how we should be listening. This is especially true when we try to understand what listening is and how we identify when someone is listening. For example, writing consultants in our center readily identify key physical performances such as eye contact, backchannelling, and note taking as evidence that the student writer is listening. However, students of various backgrounds and with diverse identities, such as students with disabilities, often do not conform to these narrow prescriptions of listening. Our study responds to the call for more research and training protocols to create stronger intersections of welcome for students with disabilities.

Methods and Institutional Contexts

We conducted our research at the University of Nevada, Reno, a mid-size public PhD granting institution in the west. As of the fall 2018 semester, our university is home to approximately 20,000 undergraduate and graduate students (University of Nevada, Reno, 2018). Our writing center is located in a newer building, opened in 2015, in the center of our campus. The building consolidates various academic student services, which were previously located across the campus, including tutoring centers, the Disability Resource Center, and Student Veterans Affairs. The writing center that was the focus of this research is primarily supported with student fees. Annual one-on-one and small group consultations are approximately 9,000 each year. The writing center has approximately 45 writing consultants, one administrative assistant, and one full-time director.

While we do not track information regarding student’s disability status, data collected by the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment (2018) helps us to get an idea of how disability may impact our undergraduate student population. Their current survey data for the Fall 2017 semester indicates that, among the fifty-two colleges and universities that are currently participating, the following percentages of students identified as having been diagnosed or treated by a professional within the past 12 months for the following conditions: Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (8.9%); Chronic illness (e.g., cancer, diabetes, auto-immune disorders) (5.5%); Deafness/Hearing loss (2.3%); Learning Disability (5.1%); Mobility/Dexterity disability (1.0%); Partial Blindness (2.8%); Psychiatric condition (8.8%); Speech or language disorder (1.1%); Other disability (2.9%). In addition, students reported the following conditions as having affected their individual academic performance (performance defined as received a lower grade on an exam or an important project; received a lower grade in a course; received an incomplete or dropped a course; or experienced a significant disruption in thesis, dissertation, research, or practicum work): Anxiety (26.2%); Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (6.5%); Chronic health problem or serious illness (4.3%); Chronic pain (3.5%); Depression (17.6%); and Learning Disability (3.6%).

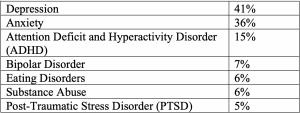

Degner, Wojciehowski, and Giroux (2015) modified an early version of the National College Health Assessment and distributed it to writing center consultants and administrators at their home institution between March 2014 and January 2015. Table 1 demonstrates that of the 127 responses they received, 57% reported having experienced symptoms of one or more of the following health concerns:

What these figures tell us is that, while students with disabilities may be a statistical minority on college campuses, a significant number of students are affected by various conditions that may or may not accompany formal diagnoses or treatment. For example, while only 8.8% of students identified as having a psychiatric condition, 17.6% of students reported that depression had a negative effect on their academic performance (Degner, Wojciehowski, & Giroux, 2015). Because of this, we do not seek to connect listening to any specific disability or to suggest that students should identify as disabled for purposes of writing center consultations. Instead, we ask ourselves, how can recognizing the presence of disability in the writing center help us understand listening and thus create a greater sense of care and welcome for all students?

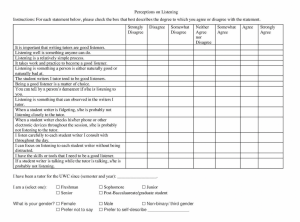

To begin exploring how focusing on listening within writing center consultations may help students—especially those with disabilities—to feel welcome in the center, we spent two years developing and implementing a series of training sessions. This project proceeded in two phases. In phase I, we surveyed our writing consultants’ attitudes and beliefs about listening during the spring 2017 semester. Using the results of this survey, we developed a one-time consultant training presentation that connected listening and disability within the context of writing center consultations. Prior to the training session, we gave our writing consultants a second survey that asked them follow-up questions about their attitudes toward listening (see Appendix A), which we administered again two months after training.

What we found was that, while students were engaged in the training session and eager to improve their tutoring practices, their attitudes about listening did not change in the post-test survey. We wondered if writing consultants needed more consistent exposure to talking about listening and disability, and so in phase II of the research project during the spring 2018 semester, we conducted “listening lessons,” specific training sessions that addressed issues related to listening to respond, listening to shelter, and disabilities within the context of writing center work, during monthly consultant meetings, as well as during the pre-semester orientation. We again distributed the survey during the pre-semester orientation and again at the end of the semester.

After collecting the responses, we coded the discursive data using in-vivo coding during the first-cycle coding process and pattern and axial coding during the second-cycle coding process (Saldaña, 2016). During the first-cycle coding, we focused on creating categories that revolved around patterns of language that the writing consultants used themselves (Saldaña, 2016, p. 105) and allowing their words to create patterns for observation. From there, we used in-vivo coding to focus on axial and pattern coding to determine which patterns manifested as more prominent than others (Saldaña, 2016, p. 236). Our goal in blending these three coding approaches was to pay attention to how the writing consultants picked up and implemented the training we were presenting from their perspective while also attempting to capture those patterns that occurred more frequently than others without dismissing less predominant patterns out rightly. Following are the results from our intervention project.

Results

Phase I Results: Distraction and Listening

During phase I, we learned that consultants consider listening to be central to the success of the work they do in the writing center and refer to listening in a broad sense, typically referring to hearing and understanding what someone has said. The pre- and post- test results of the consultants’ survey of perceptions of listening indicated that all respondents (36 in the pre-test and 20 in the post-test) strongly agreed at the beginning of the semester and the end of the semester that it is important that writing consultants are good listeners. Additionally, they agreed with the statements, ‘I listen carefully to each student writer I consult with throughout the day’ and ‘I can focus on listening to each student writer without being distracted.’ These results lead us to believe that, while listening is central to our consultants’ perception of writing center work, it may also be perceived as a common-sense task, something that automatically happens without needing to interrogate the practice or to be intentional in the use of listening within consultations.

When we began phase I, we asked writing consultants to think about the challenges they face when trying to listen to a student writer during consultations, to identify what student writers may do during consultations that may make it difficult to listen, and to narrate a specific writing consultation where the consultant struggled to listen to a student writer. During Phase I, we were surprised to hear the ways in which writing consultants struggled to listening during consultations because a student writer engaged in silence. During our discussions during training session, some consultants also added that they sometimes perceived a writer’s silence as an act of resistance born out of either the writer’s laziness (the writer doesn’t really want to do the work of improving the draft) or defiance (when writers are told they should or must get help from the writing center as part of a grade). These attitudes demonstrate that silence is not perceived as a generative act but is consistently perceived as a lack of some kind or a failure on the part of the student writer.

A second significant theme to emerge was how writing consultants indicated that various bodily habits and performances distracted their ability to listen as well as how silence (or not talking) was also a noted distraction. Following are examples of the distractions writing consultants noted:

- Slow or fast speech, strong accents, mumbling, speaking softly;

- Not talking or talking for extended periods of time;

- Students who repeat themselves while talking;

- Talking down at the table or at their laptop;

- Continuously moving, fidgeting, leg shaking;

- Touching their phone or looking at their phone;

- Biting fingers or clothing;

- Looking down or making uninterrupted eye contact;

- Closed body position;

Consultants’ perception that they can listen to each student writer without being distracted was contradicted in their responses to a writing task, which asked them to reflect on the following prompt: “Think of a specific tutoring session that you had where you struggled to listen to a student writer. Describe the session, focusing specifically on what was occurring that made it difficult to listen. How did you try to overcome your difficulty in listening?” During this exercise, our consultants articulated complex writing center scenarios that challenge the belief that listening is an easily controllable and automatically accessible skill. For example, one consultant explained how the physical space of the center impacts their ability to listen: “I have a really hard time with the rooms that 2 consultations take place in at the same time. If someone is having a side conversation and I’m supposed to be listening, it throws me off in all contexts.” This consultant’s reflection highlights the ways in which physical and social spaces impact our ability and willingness to listen. While the consultant wanted to stay engaged with the student they were working with, the presence of other voices limited their ability to do so. This leads us to believe that, while consultants perceive listening as a straightforward strategy, their own experiences could help them complicate their understanding of listening.

The potential implications for the accessibility and welcoming nature of our writing center are serious. While we do not know the identity of the writer, auditory distractions, such as side conversations while one is trying to focus on a consultation, could prove problematic for a wide range of writing center users, including students with disabilities. We wanted to highlight this during our phase I training session. When we showed the consultants this anonymous response, we were surprised at how many agreed that this particular consulting space can impact listening and, more importantly, why nobody else had thought to mention it in their responses. Rather than seeing the ways in which the layout and design of our center may impede easy listening, our consultants seemed more likely to attribute failures in listening to a personal deficiency. Take, for example, two other writing consultant responses, which highlight this point:

- “When it’s difficult to listen, the difficulty is coming from me, and is usually the result of difficulties stemming from my own mental circumstances (stress, preoccupation, etc.).”

- “I was distracted a little bit because the student’s thoughts weren’t really organized. I couldn’t take table notes and so I kind of checked out.”

In the first response, the failure of listening is attributed as a personal failure on the consultant’s part; the second response incorporates a personal failure to listen while also deflecting ‘responsibility’ to the writer’s lack of preparedness.

Phase II Results

During phase II, we designed monthly training activities that would engage our writing consultants in sustained dialogue about listening throughout the spring 2018 semester. The topics ranged on theories related to different types of listening, such as listening to respond and Heidegger’s notion of listening to shelter (Fiumara, 1990; Ratcliffe, 2005), the intersections of listening and disability studies, and complicating notions of ‘active listening.’ In the next section, we report on several patterns and themes that emerged in the writing consultants’ written and verbal feedback during these training sessions.

Listening and Welcome

One of the benefits of listening that writing consultants gravitated towards was how they saw listening as an important element of making writing center users feel welcome. During the first training session in phase II, of the 46 written responses collected, 10 (21.7%) specifically reflected upon issues of welcome. Writing consultants connected listening to making students feel comfortable working with the consultants. Our writing consultants reflected on a range of experiences, such as the following:

- “Listening…help[ed] the session because it was a good way to establish rapport and demonstrate that I care about what they [the student] had to say. The student was from across the world and I found the student appreciated this way of listening since it was the opposite of what they did in her home country.”

- “In one of my recent consultations, the student told me a lot about her life story. She explained some really deep, personal stories that shaped her into who she is. I purposely listened to shelter, and I think it was very effective. She knew she had someone to just listen and not judge. I looked at the world through her eyes and I think it helps strengthen our relationship. The appointment went well, and she has come back a few times.”

As we examine our consultants’ accounts, we are impressed with the connections they make between listening and welcome. What we are finding is that creating a sense of welcome seems to be less about building a particular aesthetic and more about establishing connections between consultants and student writers that make the writers feel valued, cared for, and sympathized with. In fact, one of the most recurring themes that has emerged over the course of phase II was the role that empathy plays in creating a welcoming space (during the first training session, 15 of the 46 responses—32.6%—were coded as mentioning empathy or sympathy).

Empathy emerged among writing consultants in a variety of ways. For some, remembering their own experiences as a new student or even in a specific course was the gateway for them to access empathy. We can see this emerge in the following writing consultant response:

“I work a lot with CHS 211 students, which can be a very rigorous class. In order to help the students understand, I always have to put myself in their shoes and remember what it was like at the beginning of this class. You have to fully and actively listen and work with the students or else you will get nowhere with the student, so I typically always listen… otherwise I would not be able to have a peer-to-peer conversation with them.”

For other students, the process of actively listening to personal experiences and narratives, even if they were far from their own experiences, was crucial:

“I am a new consultant this week. One of my consultations was a film review about the movie Crash. In the paper, the student needed to explain which character she related to and why. She wrote about sexual harassment and about racial discrimination against her mother. I feel like I had to employ both ‘listening to respond’ and ‘listening to shelter’ because of two reasons. One, I could only partially relate to her experiences and wanted to focus on her feelings. Two, I was asked to give my thought about what information was needed and how it related to the movie. I needed to know what she wanted from me as a consultant, but to be respectful.”

Most of our consultants indicated that at some point in the semester, they worked with students who disclosed personal details about their lives: the struggles of an international student living abroad, domestic violence, and working with Veterans reintegrating after their service, to name only a few. While we did not originally conceive of empathy as necessarily part of our definition of listening to shelter, we are impressed at our consultants’ ability to make the connection between empathy and the transformative ethos we sought to cultivate. In retrospect, we see now how empathy is central to listening to shelter. By empathizing with the student writers, we see our consultants approaching their work from a generous space in which they are more likely to be attentive to what the writer said and needed.

The results suggest that our writing consultants see listening as the key to unlocking empathy. We see the process of cultivating empathy as one way in which our writing consultants embody listening to shelter. As previously discussed, for Heidegger, listening is better understood as a process of safekeeping (Fiumara, 1990, p. 4; Ratcliffe, 2005). This process of gathering in order to protect is what governs our sheltering of another’s words, ideas, and feelings: “accommodation governs the sheltering” (Fiumara, 1990, p.4). In order to “shelter” the ideas of another, listeners must be willing to resist rejecting a person’s ideas, to jump in with rebuttals or qualifications, or to take over the idea’s development. Empathy provides the intellectual, emotional, and social spaces in which consultants can engage listening to shelter and consider the student writer’s work in such a way that the writer may feel as though their work is welcomed in the center, which we hope translates into more students feeling at home in the center. Additionally, the consultants’ awareness of how listening in more nuanced ways can provide a safe space for students reflects the suggestions of Degner, Wojciehowski, and Giroux (2015).

Listening and Disability

After our first listening lesson during phase II, which focused primarily on thinking about different reasons and motivations for listening, we began to reintroduce topics related to disability in the writing center. During our second monthly session, we again discussed the ways in which ideologies of ableism (Siebers, 2011) are built into physical and social structures, as well as the policies and procedures of the writing center. From there, consultants began to develop ways their practices could be adapted to be more inclusive of all bodies, regardless of whether or not they knew the writing center user identified as disabled (see Appendix B). The following month, we distributed that list and asked them to think about times when they worked on implementing those practices and what effect they had on their sessions.

During these training sessions, consultants demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of how they might improve their practices. Of the 38 consultants who submitted responses, 15 (39.47%) of them specifically generated strategies that involved adjusting their expectations and practices regarding listening. These suggestions included:

- “Both being willing to listen to what they [say] and do”

- “Listen to them as if they didn’t have a disability.”

- “Increase [awareness of] body language to make it obvious you are listening to someone.”

- “Understanding different listening styles.”

- “Listening actively/checking for understanding to ensure communication of an idea.”

- Asking students “what support do you want in the consultation rather than [relying on] past experiences or the agenda form.”

When we asked consultants to reflect the next month on their experiences implementing the strategies we developed in any and all sessions (not necessarily those with students who may have disclosed a disability), we again noticed how issues of listening and welcome continued to surface. Of the 33 responses collected, 10 consultants (30.3%) focused their reflections on how the strategies seemed to make writing center users feel more welcome, and 9 (27.27%) focused specifically on strategies involving listening. The following response portrays a recurring theme:

“I have focused on adopting the ideology of listening to the writer, not the document. After reflecting on myself as a consultant, I realized that I spent too much time engaged with the paper as a separate entity from the writer. Upon this realization, I have taken steps to interact more with the writer.”

The consultants’ realization that they sometimes get too focused on what they are working on during a consultation, rather than who they are working with is in part attributed to our ongoing discussions about listening. Our consultants continued to focus on how listening can create rapport and empathy between consultants and writers may be impacting this consultant’s understanding of what his or her job really is: not just to help a writer create, draft, or revise a written text, but to also work with writers themselves—a job we cannot do if writers do not feel welcome and at ease in our center.

A second consultant wrote about a student writer who disclosed an attention disorder in order to apologize for potentially being “sporadic” and scattered during the consultation. The consultant recalled:

“With that in mind, I tried to assure the student that they were allowed to talk about whatever she needed and if any other writing concerns came up to mention them when she saw fit. We jumped around with a lot of ideas and not necessarily on one track, but by the time we wrote her summary report, it was clear to me that she processed a lot internally and connected the ideas on her own. Letting students say what they need to say may be what works best for them.”

In four of the responses, consultants noted how training could support efforts to understand, identify, and support students with disabilities. Consultant responses included requests for training regarding different learning disorders and non-standard thinkers and training to teaching consultants how to read/listen for anxiety in body language, including understanding their own body language cues that they are giving out.

As we examine this consultant’s reflection, we notice first and foremost that the student writer felt the need to apologize for wandering off track during the consultation. While this is common in many tutoring consultations, the student’s sense of identity may be informed by a multitude of experiences in institutional settings in which teachers, advisers, peers, etc. may have expressed frustration with her ability to stay focused. The consultant’s awareness that listening to this disclosure with empathy and adjusting their listening expectations to accommodate this student demonstrates the consultant’s commitment to making all students feel welcome in the center. Our writing consultants’ adjustment from expecting that student writers should behave a certain way to an awareness of bodily difference in the center is a critical shift toward listening to shelter. This frees up our consultants’ thinking and allows them to focus on listening empathetically and generously so that student writers can get the writing support, emotional support, and social support they need to be successful in their work and to feel comfortable and at ease in returning to the writing center in the future.

The final survey from the end of the 2018 intervention session asked consultants what the results of the intervention had been for them. Over half of the consultants (23 of 43) wrote about their heightened sense of awareness of the importance of listening. Consultants also noted that they were more likely to look for cues that students they work with are listening and to listen more intently to what students want (suggesting that listening to respond should not be the initial purpose of listening).

Over the course of phase I and phase II, we found that there were no significant changes in writing consultants’ responses on the survey, a point we discuss in more detail in the conclusion.

Discussion

We have noticed that discussing listening on a regular basis created opportunities for writing consultants to help each other create meaningful writing consulting practices that would better prepare them to meet the academic and emotional challenges students bring to writing centers. Moreover, it helped us to transform these experiences into sites of reflection and invention as consultants took stock of what they had done and worked toward creating better practices from those experiences. In other words, their individual and collective experiences—their lore—became the basis of developing a working theory of listening in our writing center.

While practices our writing consultants suggested may seem to be common courtesy or even assumed best practices for writing consultants, our consultants have transformed these into vital points of access in their consultations. In other words, while nothing the consultants generated is necessarily ‘out of the box’ thinking, we consider their recognition of the importance of these practices for all students to feel welcome and able to access the writing center to be a significant shift in consultants’ thinking. These practices further aligned with notions of universal design, an approach which focuses administrators and tutors on making disability always part of our worldview while also remaining flexible to the shifts in our contexts, spaces, and users (Dolmage, 2008, p. 24-25). In so doing, universal design and the approaches our writing consultants are implementing are not just to increase the sense of welcome for students with disabilities, but for all students as well (Dolmage, 2008, p. 25).

Our phase I results revealed complicated relationships between speaking, listening, and silence. In terms of listening, we are struck at how writing consultants’ perceptions of the writer’s silence can be difficult for listening. We note that our writing consultants find student writers’ silence distracting, which suggests that they favor a communication style that involves more consistent give-and-take repartee. Moreover, this kind of conversation may not work for all students for various reasons: our writing consultants may be asking questions or making comments that the writers have yet to consider, prompting the need to contemplate before responding verbally. Other students may wish to take more time to process what has been discussed, to take notes, or may have other needs before responding. Our writing consultants’ perceptions that silence is distracting—rather than seeing it as generative—is indicative of the ways in which listening is largely undertheorized or considered in higher education. Our writing consultants bring these assumptions to their work in the writing center, unless (or until) these assumptions are intervened. These early results were part of the impetus for developing phase II of this project.

The writing consultants initially identified an ableist notion of listening or able-bodied normative standards in which they understood student writers to be engaged in listening when they made eye contact, used backchannelling, and other bodily habits and performances, which could be due to the persistence of ableism as a central paradigm for many students raised and educated within the United States. What is most striking about the list of physical and bodily distractions generated by our writing consultants during phase I (see Results section) is that students with disabilities may be more likely to be implicated as breaking unspoken normative social cues than students who identify as able-bodied. For example, in Hitt’s (2017) foreword to Writing Centers and Disability, she describes how her own experiences as a person with a disability in the writing center highlight this point. She notes that, “I am hyper-aware of my body in writing center spaces because I exhibit a lot of behaviors that are considered non-normative: I avoid eye contact with students and scratch at my arms and hands during consulting sessions. I ask students if they are okay with not reading their papers out loud because I am not an auditory processor and need to read essays silently in order to understand and be able to discuss the content” (pp. viii). Hitt seems to exhibit many of the behaviors listed by our writing consultants as making it more difficult (though by no means impossible) to listen, and yet Hitt deserves just as much attention as a student who can presumably sit still, make eye contact, and respond to questions and comments in turn. This initial result led us to believe that writing consultants’ attitudes about listening, especially as they pertained to able-bodied normative standards seemed like a starting place to develop training. Furthermore, what concerned us about these attitudes is that many writing consultants seemed to align these behaviors with students who were lazy, who were only coming to the writing center because they were ‘forced’ by an instructor or for extra credit,[2] and typically the ways in which they characterized such students as not being invested in their consultations, rather than interpreting these behaviors as anxiety-based, fear-based, or even as evidence that the student is experiencing a new cultural context with which they feel unsure.

What may be worthy of future study is how some writing consultants viewed listening to respond as sometimes being in conflict with listening to shelter. After the intervention, consultants were more likely to value listening to shelter as a primary response and purpose. Listening to shelter took on a significance because it offered consultants a way to listen to others (Bokser, 2005) that they had not recognized prior to the intervention. Listening to shelter may have also provided a value to the silence that had, before the intervention, seemed distracting to consultants. Adding more training related to the value of silence for the student may help writing consultants recognize how silence is a tool within a writing consultation such as was suggested by Day Babcock (2012).

Consultants’ requests for training to understand body language (theirs and the body language of students they work with) suggests that this intervention in listening helped our writing consultants move beyond the more common perceptions of listening toward an understanding of the complexities of listening and of supporting students with differing abilities. Over the two phases of this project, our consultants have moved beyond easy assumptions about listening toward more complicated constructions of the role it plays in helping student writers feel more welcome in our writing center. Writing consultants have started to listen more (Santa, 2016) and to listen in new ways. The change in their thinking, and in our center’s ethos, is particularly important if writing centers hope to use universal design to create safe spaces for students with disabilities to work on their writing.

Conclusion

Because listening is not tied to the physical space of our writing centers, it offers a much more responsive and inclusive way to create a sense of “welcome.” Instead of creating a home within our writing centers for a projected user (McKinney, 2013), listening allows writing consultants to access more of the guests’ ideas and allows consultants the flexibility that we are seeing in new types of housing and vehicles (see the new origami inspired car[3] or the new tiny home that folds out from a container[4]).

This research reveals the complicated relationships our writing consultants have with listening. For example, our research demonstrates that writing consultants can identify the complexity of listening to students of diverse backgrounds and with unique needs, but their listening practices are informed as much by their own needs and situations as they are by their commitments to treat listening as a complex, ethical practice. The results of this research lead us to conclude that, in order for student writers to feel welcome in the writing center, centers must be places where students are listened to in ways that respect their experiences and respond to their bodily and academic needs.

One point for further research that our findings suggest has to do with why the writing consultants’ attitudes on the perception survey did not significantly change (see Appendix A). As we reflect on how we wrote and administered the survey and what the consultants commented on during phase II, we notice that the consultants perceive listening to be emergent from the specific contexts of particular writing consultations, yet the survey asks consultants to think about listening as an abstract, generalizable concept. We see now that the presentation of listening as an abstract concept rather than emerging directly from individual consultants may be a factor in why the instrument captured no significant changes. Future research into listening and welcome may consider revising perceptual surveys to reflect listening as kairotic and related to individual writing consultants.

Our ongoing work in transforming listening into a point of access and welcome is one way our center has worked toward creating a transformative ethos for our center (Blazer, 2015). Rather than defining listening in instrumental or transaction terms, our consultants have shown us how being listeners can change who we are in order to make our center a welcoming place for all students.

Author Biographies

Maureen McBride is the Director of the Writing & Speaking Center at University of Nevada, Reno. Her research has appeared in Assessing Writing, College Composition & Communication, and The Peer Review. Her research interests include peer-to-peer collaboration, writing assessment, reading-writing intersections, language identities, and concerns of student investment, as well as writing center studies more broadly.

Leslie R. Anglesey is a PhD candidate in the Rhetoric and Composition program at University of Nevada, Reno. Her researcher interests include composition pedagogy, disability studies, feminist rhetorics, and writing center studies.

References

American College Health Association. (2018) American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Undergraduates Executive Summary Fall 2017. Retrieved from: http://www.acha-ncha.org/reports_ACHA-NCHAIIc.html.

Babcock, R. D. (2012). Tell me how it reads: Tutoring writing with deaf and hearing students. Washington, DC: Gallaudet UP, 2012.

Babcock, R. D. (2015). Disabilities in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1), 39–50.

Babcock, R. D., & Daniels, S. (2017). Writing centers and disability. Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press.

Babcock, R., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center: Towards an evidence-based practice. Peter Lang.

Blazer, S. (2015). Twenty-first century writing center staff education: Teaching and learning towards inclusive and productive everyday practice. The Writing Center Journal, 35(1), 17-55.

Bokser, J. A. (2005). Pedagogies of belonging: Listening to Students and peers. The Writing Center Journal, 25(1), 43-60.

Daniels, S., Babcock, R. D., & Daniels, D. (2015). Writing centers and disability: Enabling writers through an inclusive philosophy. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1), 21–27.

Degner, H., Wojciehowski, K., & Giroux, C. (2015). Opening closed doors: A rationale for creating a safe space for tutors struggling with mental health concerns or illnesses. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131.

Dolmage, J. (2008). Mapping composition: Inviting disability in the front door. Disability and the teaching of writing: A critical sourcebook (pp.14-27). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Elston, M. M. (2015). Psychological disability and the director’s chair: Interrogating the relationship between positionality and pedagogy. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/links-page-131

Fiumara, G. C. (1990). The other side of language: A philosophy of listening. New York, NY: Routledge.

Garbus, J. (2017). Mental disabilities in the writing enter: Challenges, strategies, and opportunities. In R. B. Babcock & S. Daniels (Eds.), Writing centers and disability (47- 77). Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press.

Geller, A. E., (2013). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Hitt, A. (2017). Foreword. In R. B. Babcock & S. Daniels (Eds.), Writing centers and disability (47-77). Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press.

International Writing Center Association (IWCA). (2006). Position statement on disability and writing centers. Retrieved from http://writingcenters.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/disabilitiesstatement1.pdf.

Jackson, S. & Blythman, M. (2017). “Just coming in the door was hard”: Supporting student with mental health difficulties. In R. B. Babcock & S. Daniels (Eds.), Writing centers and disability (233-256). Southlake, TX: Fountainhead Press.

Kiedaisch, J., & Dinitz, S. (2007). Changing notions of difference in the writing center: The possibilities of universal design. The Writing Center Journal, 27(2), 39–59.

Lunsford, Andrea. (1991). Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center. Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3–10.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Mullin, A. (2002). Serving clients with learning disabilities. The Writing Center Resource Manual. Ed. Bobbie B Silk. Emmitsburg, IWCA Press. IV.1.1-IV.1.8.

Ratcliffe, K. (2005). Rhetorical listening: Identification, gender, whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP.

Rinaldi, K. (2015). Disability in the writing center: A new approach (that’s not so new). Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). Retrieved from https://www.praxisuwc.com/rinaldi-131

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage.

Santa, T. (2016). Listening in/to the writing center: backchannel and gaze. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 40(9-10).

Siebers, T. (2011). Disability Theory. University Press of Michigan.

Stenberg, S. (2011). Cultivating listening: Teaching from a restored logos. Silence and Listening as Rhetorical Arts. Glenn, C. & Ianetta, M. J., Eds. 250-263.

University of Nevada, Reno. (2017). F16 to F17 Census Comparison Diversity Site. Retrieved from https://www.unr.edu/Documents/president/diversity/F16%20to%20F17%20Census%20Comparison%20Diversity%20Site.pdf

Appendix A

Consultant Survey: Perceptions on Listening

Appendix B

Strategies for Meeting the Needs of Students with Disabilities: Brainstorming 3/9/2018

- Listen with abundant amount of patience

- Don’t ask too many questions (it may overwhelm writers)

- Accommodate more than 30-minute consultations

- Ask students where/how they want to conduct appointment

- Option on online form to disclose disabilities like hard of hearing

- Raise awareness that the writing center welcomes people with all ability types.

- Write down key terms the student says on the whiteboard table (where you both can see it)

- Make it clear that we can accommodate our expectations

- Have more walk-in consultations

- Spend more time listening before working

- Be more mindful

- Make it part of front desk training to make sure we open the front door

- Consider outside appointment options

- General questions tutors can ask: do you need me to rephrase that? Would you like me to say that again?

- Offer students the opportunity to write out concerns and issues

- Adjust expected time needs as you go through the consultation

- Sympathize with worries and anxieties

- Listen to the write, not the document

- Pause you thought process to listen to students

- Ask students if they want the door opened or closed during consultations

Potential Consultant Quotes for Call-Out Boxes

- “If someone is having a side conversation and I’m supposed to be listening, it throws me off in all contexts.”

- When it’s difficult to listen, the difficulty is coming from me, and is usually the result of difficulties stemming from my own mental circumstances (stress, preoccupation, etc.).”

- “I was distracted a little bit because the student’s thoughts weren’t really organized. I couldn’t take table notes and so I kind of checked out.”

- “I purposely listened to shelter, and I think it was very effective. She knew she had someone to just listen and not judge. I looked at the world through her eyes and I think it helps strengthen our relationship.”

- “I have focused on adopting the ideology of listening to the writer, not the document. After reflecting on myself as a consultant, I realized that I spent too much time engaged with the paper as a separate entity from the writer. Upon this realization, I have taken steps to interact more with the writer.”

- “Listening…help[ed] the session because it was a good way to establish rapport and demonstrate that I care about what they had to say. The student was from across the world and I found the student appreciated this way of listening since it was the opposite of what they did in her home country.”

- “Mental disability” is a term often used to loosely describe what are called “mental illness” or “psychiatric disorders,” and is used to characterize conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders (among others) that have biological, social, and psychological components (often called ‘biopsychosocial disorders) (Garbus, 2017). ↑

- Comments relating to issues of laziness or being forced to come to the writing center were expressed verbally during the listening lessons and not in writing ↑

- Here is a link to a video about the origami inspired car: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pVlUIBKXVX4. ↑

- Here is a link to a video about a fold-out tiny home: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gttzfJr8jb8 ↑