Krista Speicher Sarraf

Writing centers aim to serve all students, but, for various reasons, not all students visit the writing center (Salem, 2016). At my home institution, Indiana University of Pennsylvania (IUP), a mid-sized public research institution in rural Western Pennsylvania, one such population of students is computer science majors who must be able to communicate to compete in a competitive job market where writing is often high-stakes. In a study of employers by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (2013), over 75% of employers listed written and oral communication skills as one of five key areas they wanted schools to emphasize. With jobs that demand that cybersecurity professionals be competent with technology and writing, collaborations between writing centers and technical fields are crucial.

This article describes one such collaboration and offers a theory-based workshop model that draws on laboratory approaches to writing (Lerner, 2009). The workshop is discussed in context of writing center research, collaborative learning theory (Bruffee, 1984), and theories of writing as experimentation (Murray, 1972). After a description of the theoretical framework, I then describe the simulation-based workshop and apply the framework to it. Ultimately, I offer this simulation-based workshop as a theoretically-grounded writing center practice that may help writing centers to welcome computer science students.

Computer Science Majors in the Writing Center

In response to a growing demand for writing skills, the National Security Agency (NSA) awarded IUP a grant for 2017-2018 to improve the written communication skills of students interested in cybersecurity careers, and, as a graduate assistant assigned to work with Ben Rafoth, I was tasked with helping the writing center to enact the grant’s goals. The grant project’s CO-PIs—Waleed Farag (Computer Science), Dighton Fiddner (Political Science), Crystal Machado (Department of Professional Studies), and Ben Rafoth (English), created an interdisciplinary team designed to identify challenges that cybersecurity students face and to implement solutions. As a member of the research team for the grant’s research project (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a), I helped to conduct interviews with cybersecurity professionals and surveys with computer science students. The results of this research allowed the writing center to design new learning experiences for computer science students that addressed the challenges that students may face upon entering their professions.

The research study (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a), resulted in several findings that helped to shape our writing center’s approach to working with computer science students. For example, interviews with professionals revealed that the top five kinds of writing done at work by cybersecurity professionals are email, reports, procedures, training modules, and documentation (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a). What these kinds of writing share in common in the cybersecurity context is that the audience is often someone outside the technical field. Indeed, professionals also tended to note in interviews that writing for non-technical audiences is a challenge (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a). The quantitative report reinforced the findings of the qualitative report, as some students we surveyed reported concerns about writing effectively for people without technical knowledge of their field (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a). Based on the results of the mixed-methods study, our aim in the writing center was to develop resources to help prepare students for the reality of writing in cybersecurity.

Visits to the Writing Center: COSC Students as “Non-Visitors”

To understand our writing center’s current engagement with computer science students, the grant team tracked the number of writing center visits that occurred before and after the initiation of the grant (CAE-C-Expansion Project, 2018a). A search of writing center tutoring session records between October 14, 2014 and September 1, 2017 returned records for 14 tutoring sessions that focused on computer science assignments (one in Spring 2017, five in Fall 2016, four in Spring 2016, three in Fall 2015, and one in Fall 2014). The dearth of computer science tutoring sessions in our writing center raised an interesting question: If computer science papers are rarely the topic of tutoring sessions, how can the writing center engage with computer science students? What should our writing center make of these non-visits? Lori Salem (2016) writes that writing centers should not only investigate the needs and experiences of students who visit the writing center; writing centers also should study students who do not come to the writing center, or “non-visitors” (p. 161), as these students compose the majority of college students. Salem (2016) asks several questions about non-visits:

If someone doesn’t visit the writing center, does that mean that they don’t have any questions about their writing? Or does it mean that they have questions, but they are choosing to ask someone else? Or does it mean that they have questions, but they are choosing not to ask them at all? And if they are choosing not to ask them, is that because they simply don’t care enough about their assignments? Or is it because they are embarrassed to seek help (p. 162)?

Or, in the case of IUP’s writing center, what does the low number of face-to-face peer tutoring sessions for computer science papers tell us about this population?

As I explored the writing center field’s literature, I began to question whether the appropriate response to the dearth of computer science visits was to try to attract more students to one-to-one tutoring sessions. Perhaps I had been taken in by the narrative that the writing center’s main activity is, and should be, tutoring. As Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2013) writes, “when we say, as we do at my center, that we work with all students, we lie. We are telling a story. It’s a better bet than saying that we will work with anyone but we know only about a quarter of students will take us up on our offer” (p. 73). McKinney (2013) continues to write that, as dismayed as writing centers may be about it, not every student wants tutoring. And, as McKinney (2013) writes, while writing centers may claim tutoring as their main activity, writing centers engage in diverse activities beyond one-to-one peer tutoring. For example, our writing center, and many others, offer workshops on discrete writing issues. For example, our workshop on using transitions augments the kinds of writing that students already do for their classes. In this way, our transition workshop, or any other workshop we offer, may be valuable for computer science students. Yet, these workshops tend to focus on writing that students generate outside of the workshop and may, therefore, be less effective for computer science students who may not write frequently for their classes. This led me to wonder: how are other writing centers structuring their workshops?

A keyword search for peer-reviewed books and articles about writing center workshops in academic databases yielded interesting results. A closer investigation of these sources suggests that workshops tend to be mentioned in the literature but are rarely the primary focus. For example, in their 2015 study, “Undergraduate Perceptions of the Writing Center,” Joseph Cheatle and Margaret Bullerjahn write that faculty outreach, including faculty workshops, are important for “changing student perceptions” (p. 25) of their writing center. Beyond recommending workshops to engage faculty, other articles mention workshops alongside a list of other services the authors’ writing centers offer (Barron & Cicciarelli, 2016; Kelly & Head, 2017; Kramer, 2016). These authors say that their writing centers offer workshops, but workshops are not at the center of these articles’ discussions.

While the above sources point to one-to-one tutoring as the main focus in the literature, other research more closely attends to non-tutoring activities. Cory Hixon et al. (2016) describe the Virginia Tech Engineering Education Writing Group (EEWG), a weekly writing group for engineering students that “resembles Neal Lerner’s conception of a writing laboratory – a place where the physical act of writing happens as visible everyday work” (p. 20). Writers in an EEWG session produce new writing, share their work, and give each other feedback, “reflecting an ongoing process of creating and talking about texts” (Hixon et al., 2016, p. 20). Hixon et al.’s (2016) discussion of EEWG is one example of scholarship that explores writing center activities beyond peer-to-peer tutoring. Another is Beth Godbee, Moira Ozias, and Jasmine Kar Tang’s (2015) discussion of a movement-based workshop for tutor education that aims toward “radical justice” (p. 63). Their research argues that movement-based workshops acknowledge that, “our bodies and the spaces we inhabit shape our identities and carry legacies of social structuring, power, oppression, marginalization, injustice” (Godbee, Ozias, & Tang, 2015, p. 62). By centering the discussion of movement-based education within critical theory, communities of practice, and racial justice, Godbee et al. (2015) propose movement-based workshops as a critical approach to tutor education. Both Hixon et al.’s (2016) discussion of writing groups and Godbee et al.’s (2015) discussion of movement-based workshops are examples of recent scholarship about writing center practices beyond peer tutoring. The present research continues that discussion by situating a simulation-based workshop for computer science students within a theoretical framework.

Since the workshop our writing center developed is different from our writing center’s regular activities, I offer the workshop as a new way of welcoming computer science students. Further, the workshop responds to McKinney’s recent call to take seriously alternatives to tutoring. McKinney (2013) traces the vast amount of non-tutoring activities in writing centers but says that these activities “are seldom theorized as something potentially pedagogically important on their own” (p. 76). Rather, non-tutoring activities are treated as “a way to advertise or spread goodwill about the tutoring services, as a resource to use in a tutoring session, or as a resource for training tutors. The existent literature rarely posits these other activities as alternatives to tutoring or something equally important” (McKinney, 2013, p. 76). If our writing center had not traditionally engaged computer science students in large numbers in tutoring sessions, might a simulation-based workshop be a valid alternative? My aim below is to theorize the simulation-based workshop as a pedagogically-sound writing center activity.

Theorizing a Simulation-Based Workshop

What theories of learning are useful for understanding simulation-based workshops? To explore this question, I turned to Neal Lerner’s (2009) account of the origins of writing centers, The Idea of a Writing Laboratory, which helped to renew the idea of writing as experimentation and offered writing centers new ways to conceive of themselves as sites for play through situated learning. As has been suggested by Lerner (2009), as well as Elizabeth Boquet (2002) and others, writing centers have their roots in experimentation, laboratory learning, collaborative learning (Bruffee, 1984; Lunsford, 1991), and situated learning. Lerner (2009) writes that writing instruction can be “untethered from traditional classroom contexts and can flourish in contexts where students are engaged in meaningful practices” (p. 195). I read Lerner’s (2009) statement as an invitation to writing centers to involve students beyond one-to-one peer tutoring sessions and to engage with writing that originates outside of the classroom.

Writing centers have their roots in laboratory methods, which emphasize experimentation and the writing process. Donald Murray first wrote in 1972 that writing should be taught as a process, not a product, and that students should treat drafting as a process of discovery. Process pedagogy has since become more nuanced; for example, Nancy Sommers (1980) agreed with Murray (1972) that writing is a process, but she added that the process is recursive. Although post-process theory warns against replacing teaching writing as a product with teaching writing as a process, Murray’s original concept of writing as experimentation has staying power among compositionists (Goldblatt, 2017). Lerner (2009) takes seriously the concept of writing as experimentation by suggesting the idea of a writing laboratory in which writers play with ideas. To Lerner (2009), experimentation is “problem solving, critical thinking, an ease with the unknown, and a persistence in the face of frequent failure” (p. 5). As such, many writing centers train their tutors to view writing as experimentation. For instance, the widely used Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors (2010) reminds tutors that writing is a messy “process of discovery” (Ryan & Zimmerelli, 2010, p. 7) and that students’ processes may vary widely. Can the idea of a writing laboratory be extended beyond one-to-one tutoring to simulation-based workshops?

The simulation-based workshop described below not only draws on the ideas of writing as experimentation, but it draws on the role of dialogue. Lee-Ann K. Breuch (2002) was writing for the composition field at large when she offered dialogue as a way to enact post-process theory, which she describes as a pedagogy that emphasizes mentoring. She suggests that “the rejection of mastery and engagement in dialogue” inherent in post-process theory “help us reconsider teaching as an act of mentoring rather than a job in which we deliver content” (Breuch, 2002, p. 143). Breuch’s (2002) concept of teaching as mentoring relies on dialogic instruction between students and teachers. To Breuch (2002), teachers can make learning relevant to students’ real-world contexts by engaging in conversations with students. In this kind of classroom, students become co-investigators into the world around them by dialoguing with the teacher. The dialogue between student and teacher encourages experimental writing (Murray, 1972), as dialogue encourages students to view writing as a process not a product. Thus, I see Murray’s (1972) and Breuch’s (2002) ideas about experimentation and dialogue as two techniques that can be used to extend Lerner’s (2009) idea of a writing laboratory to the simulation-based workshop described later in this article.

Experimentation (Murray, 1972) and dialogue (Breuch, 2002) relate in context of simulation-based workshops by helping workshop participants to learn collaboratively. Dialogue between workshop participants allows groups to generate and revise ideas. Dialogue can spark experimentation, and experimentation can spark dialogue. Thus, I propose the term “experimental dialogue” to describe the experience of collaborative writing in this simulation-based workshop. Experimental dialogue relates to Lerner’s (2009) idea of a writing laboratory because laboratory methods emphasize experimentation and risk-taking over rote memorization. As Lerner (2009) writes, laboratory classes in science and engineering often group students in teams. Teams work collaboratively to problem solve; as I later show in the discussion of the simulation-based workshop, that collaboration involves experimental dialogue.

Experimentation and dialogue are also closely linked in the way scholars have thought about collaborative learning. Kenneth Bruffee (1984) wrote in his seminal article “Peer Tutoring and the ‘Conversation of Mankind’” that conversation and thought are deeply related. To Bruffee (1984), “thought is internalized conversation” (p. 90) and “knowledge is generated by communities of knowledgeable peers” (p. 95). Thus, I see Bruffee’s (1984) discussion of collaborative learning as deeply tied to experimentation and dialogue; in the simulation-based workshop, participants generated knowledge and conversed with one another in a way that reflects the values of collaborative learning theory. Thus, simulation-based workshops can be situated in theory that informs writing center practice at large. I do not mean to suggest that simulation-based workshops are more theoretically-grounded than peer-to-peer tutoring or other writing center activities; rather, I suggest that simulation-based workshops are equally valid practices and worthy of sincere consideration.

A Simulation-Based Workshop for Computer Science Students

The workshop described below was part of a series of day-long cybersecurity workshops hosted by IUP and delivered to a multi-age audience (middle school through adults). The writing center delivered three 90-minute workshops titled “‘Greetings’ from the Void: Communicating While Under Cyber Attack” on December 2, 2017; February 17, 2018; and March 24, 2018. In my discussion below, I briefly explain the simulation-based activity and analyze the aspects of workshop that encourage experimentation and collaboration (CAE-C Expansion, 2018b).[1] Throughout my discussion, my intention is to propose that theoretically-grounded simulation-based workshops like this are a way that writing centers can welcome computer science students.

The workshop our writing center developed was adapted from a tabletop exercise for the National Level Exercise 2012 developed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA originally developed this exercise to prepare private sector agencies to understand cyber threats and to improve government-private sector responses to cyber incidents. We modified the workshop to emphasize the development of a written communique that would require workshop participants to think critically about information sharing during a cyber incident. To begin the presentation, we defined “cyber incident” for participants (see Figure 1).

https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/26845

After the presenters defined a cyber incident and discussed the importance of clear incident response, participants engaged in an exercise that required them to examine information sharing during a high-pressure cyber incident and to view communication as situation-based. For this activity, participants were tasked with writing a communique to the Communications Director of an imagined company, Worldwide Global, Inc., during an imagined scenario: a cyber-attack from a hacktivist network called “The Void.” Participants learned about the nature of the attack through videos that resembled news broadcasts (see Figure 2).

https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/26845

After taking notes while watching the video about the cyber incident, participants worked in teams of four to eight people, with each team acting as the company’s Information Technology (IT) department. Because dialogue is an important part of generating ideas, teams discussed the cyber incident in detail (see Figure 3).

https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/26845

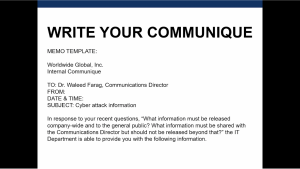

Workshop facilitators then projected a writing prompt on the screen and directed each group that they had 15 minutes to write a communique to the Communications Director (see Figure 4). Teams could use the template or deviate from it, but their central goal was to answer the Communications Director’s questions about what information should be shared company-wide and with the public. These questions prompted groups to discuss two things: 1) the nature of the cyber-attack, and 2) how to craft a message for each audience. The goal with placing participants in a simulation was to replicate the fast-paced writing typical in cybersecurity fields. By placing students in an unfamiliar scenario and asking them to write on the spot, we hoped to simulate the kind of environment of many workplaces, particularly in cybersecurity where information technology (IT) workers must respond quickly, comprehensively, and clearly to cyber-attacks. Thus, the communique writing exercise itself is a kind of experiment within the larger experiment of the simulation itself, which acted as a sort of lab in which participants role-played IT professionals.

Another aspect of the workshop—the “wildcards”—required participants to write collaboratively. “Wildcards” are index cards that contain new information about the nature of the cyber-attack. Every two to three minutes, facilitators presented groups with one of these wildcards as the groups were writing the communique:

Wildcard 1: It started two weeks ago, when our security event console detected suspicious network activities. Our system administrator conducted his daily check on the system backup server and discovered a backup error message. Upon further investigation, though, he found no additional errors and noticed nothing unusual. He logged the error message according to standard logging procedures.

Wildcard 2: A week ago, the database server on our corporate local area network crashed. After an automatic reboot, operations appeared normal, but shortly afterwards IT Support received several phone calls from users in the Accounting Department reporting that their network appeared to be slow. By noon, additional calls were received from users in other departments, to the point where IT support became overwhelmed and considered escalating the problem to management.

Wildcard 3: E-mail message from the company Chief Executive Officer: “Our productivity has dropped significantly as a result of the cyber threat rumors and unresponsive systems. I want this problem resolved asap.”

Wildcard 4: Text message from company’s legal department: “Customers who received unauthorized invoices are threatening legal action. Is anything being done about this??”

Wildcard 5: Phone call to IT Department from the company’s Chief Financial Officer: “Customers and investors are losing confidence in our systems and are not buying our products or investing in our company. This is a disaster!”

The facilitators directed teams to decide how to respond to the information on the wildcards. Wildcard 1 and Wildcard 2 included new information about the nature of the attack, so we suggested that teams integrate this new information into the communique that they were writing during this time. Wildcards 3, 4, and 5 involved communication from higher ups within the company: The Chief Executive Officer, the legal department, and the Chief Financial Officer. The wildcards resembled the kinds of messages or information that IT professionals writing a communique might receive during a cyber-attack. For example, the text message from the legal department required participants to discuss the unauthorized invoices and the actions taken in response to this question: “Customers who received unauthorized invoices are threatening legal action. Is anything being done about this??” This message created urgency and pressure. Teams discussed the legal department’s concern and found ways to address the concern in writing in the communique. In other words, the wildcard with the legal department’s anxious message required groups to pause, dialogue, and act. Other writing centers looking to implement simulation-based workshops may similarly use wildcards to encourage collaborative writing among students.

By hosting a simulation-based workshop like this one and using wildcards like the ones described above, writing centers can give students opportunities to engage in a different type of experimentation than that which occurs in peer tutoring and in teacher-student interactions in classrooms. As Lerner (2009) writes, “Conceiving of writing as a laboratory subject means creating the kind of environment that will bring these forces to bear—‘subject matter, discourse practice, other members of the community’” (p. 186). As writing centers reconsider the concept of being “welcoming” in relation to computer science students, they might consider the use of simulation-based workshops that center on subject matter and discourse practices specific to cybersecurity.

(Re)Defining Welcome: Prioritizing Simulation-Based Workshops

While much of the writing center scholarship focuses on how to create welcoming spaces or how to help writers feel welcome during tutoring sessions, I question the primacy of the tutoring session or physical spaces as the main ways to welcome new students. I do not mean to suggest that one-to-one tutorials in physical writing centers are unimportant; however, I would like to suggest that, when working with computer science students, simulation-based workshops offer a viable alternative to one-to-one tutorials. However, it should be mentioned that the present research did not investigate whether computer science students prefer tutorials or simulation-based workshops, and such an investigation might unnecessarily pit tutorials against workshops. Rather, our writing center welcomed computer science students both through one-to-one tutorials and through simulation-based workshops. To help computer science students feel more welcome in the writing center, our writing center considered simulation-based workshops as a way to not only reach students who may not be interested in one-to-one tutoring but also as a way to invite students to participate in other writing center services, including one-to-one tutoring.

The simulation-based workshop helped our writing center to meet the goal of reaching more computer science students. As mentioned earlier, 14 one-to-one tutoring sessions for computer science assignments were logged between October 14, 2014 and September 1, 2017. Between September 2, 2017 and May 12, 2018, computer science students logged 110 one-to-one tutoring sessions for computer science papers. Of those 110 sessions, 76 occurred after December 2, 2017, the date of the first simulation-based workshop. We delivered the simulation-based workshop three times to three different groups with approximately 30 participants each time, and post-workshop surveys highlighted participants’ positive reception of the workshops. Thus, the workshops and the tutoring sessions helped to increase the writing center’s involvement with the computer science department. However, it is unclear whether the workshops specifically are responsible for the increase in computer science visits. Future studies might more closely examine the relationship between workshop attendance and tutoring visits. Here, I simply wish to suggest that more attention to workshops may be useful for writing centers seeking to welcome computer science students.

Writing centers at other universities may consider simulation-based workshops to welcome computer science students. Writing centers with established relationships with departments or with writing across the curriculum initiatives may have the easiest time developing a partnership. Even if a simulation-based workshop like the one described here is not viable at some institutions, the lessons learned from this experience can help redefine “welcome” in relation to computer science students. Already, many writing centers offer writing workshops on writing skills such as thesis statements, paragraph development, and commas. These workshops could be modeled after simulation-based workshops by asking students to write something new (to experiment) during the workshop itself. Dialogue in simulation-based workshops need not be limited to the ways I described above, either. Although wildcards introduce an element of dialogue across the imagined organization in my scenario, writing centers who host simulation-based workshops can spark dialogue in many ways. For example, the activity might be adapted so that a tutor provides each team with feedback on the written communique.

Regardless of how the activity is adapted, other writing centers can use simulation-based workshops to welcome computer science students. As McKinney (2013) writes, the crux of writing center pedagogy may be peer tutoring; yet, writing centers engage in many activities beyond peer tutoring. When it comes to welcoming particular populations of students to the writing center, such as computer sciences students who are accustomed to laboratory methods and learning-by-doing, writing centers may create mini-laboratories where students generate new writing in an experimental, collaborative environment that can resemble the workplace and can enrich the writing experience.

Author Biography

Krista Speicher Sarraf is a PhD candidate in the Composition and Applied Linguistics program at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and presently serves as the assistant director of the Kathleen Jones White Writing Center. Her research interests include professional writing, digital rhetoric, writing centers, trauma studies, and creativity studies. Before beginning her doctoral work, Krista taught composition as an adjunct instructor at several colleges in Western Pennsylvania.

Author Note

Acknowledgements: This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Security Agency. Special thanks to co-principal investigators Dr. Waleed Farag, Dr. Dighton Fiddner, Dr. Crystal Machado, and Dr. Ben Rafoth. Special thanks to Dr. Machado for leading the research study.

Special circumstances: This manuscript is based on data from on a larger study titled “Enhancing Aspiring Cybersecurity Professionals Writing Skills: An Evaluation of Student and Work Force Needs for Program Improvement” described here.

References

An Online Survey Among Employers Conducted on Behalf Of: The Association of American Colleges and Universities by Hart Research Associates. (2013). It takes more than a major:Employer priorities for college learning and student success. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2013_EmployerSurvey.pdf

Barron, P., & Cicciarelli, L. (2016). Tutors’ column: “Stories and maps: Narrative tutoring strategies for working with dissertation writers.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 40(5-6), 26-29.

Boquet, E., & Lerner, N. (2008). After “the idea of a writing center.” College English, 71(2), 170-189. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472314

Breuch, L.K. (2002). Post-process “pedagogy”: A philosophical exercise. JAC, 22(1), 119-150. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20866470

Bruffee, K. (1984a). Collaborative learning and the “conversation of mankind.” College English, 46(7), 635-652. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/376924

Bruffee, K. (1984b). Peer tutoring and the “conversation of mankind.” In A. Gary & A. Olson (Eds). Writing centers: Theory and administration (pp. 3-15). Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English. CAE-C Expansion Project. (2018a). Research Study. Retrieved from https://www.iup.edu/compsci/events/cae-c-expansion/research-study/

CAE-C Expansion Project. (2018b). Writing and Communication Skills Tutoring. Retrieved from https://www.iup.edu/compsci/events/cae-c-expansion/writing-and-communication-skills-tutoring/

Cheatle, J., & Bullerjahn, M. (2015). Undergraduate perceptions and the writing center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 40(1-2), 19-26.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). (2012). National level exercise 2012: Cyber capabilities tabletop exercise. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/26845

Godbee, B., Ozias, M., & Tang, J.K. (2015). Body + power + justice: Movement-based workshops for critical tutor education. The Writing Center Journal, 34(2), 61-112.

Goldblatt, E. (2017). Don’t call it expressivism: Legacies of a “Tacit Tradition.” College Composition and Communication, 68(3).

Hixon, C., Lee, W., Hunter, D., Paretti, M., Matusovich, H., & McCord, R. (2016). Understanding the structural and attitudinal elements that sustain a graduate student writing group in an engineering department. Writing Lab Newsletter, 40(5-6), 18-25.

Kelly, C.L., & Head, K. (2017). An approach to serving faculty in the writing center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 41(9-10), 18-25.

Kramer, T. (2016). Writing circles: Combining peer review, commitment, and gentle guidance. Writing Lab Newsletter, 40(7-8), 20-27.

Lerner, N. (2009). The idea of a writing laboratory. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3-10.

McKinney, J.G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Murray, D.M. (1972). Teach writing as a process not a product. In V. Villanueva & K.L. Arola (Eds.), Cross-talk in composition theory (pp. 18-21). Urbana, IL: National Council of English Teachers. (Reprinted from The Leaflet, pp. 11-14, 1972)

Ryan, L., & Zimmerelli, L. (2010). Bedford guide for writing tutors. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions…decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147-170.

- The workshop materials, including the full workshop plan and activity wildcards, can be seen on the “Writing and Communication Skills Tutoring” page on the CAE-C Expansion website at https://www.iup.edu/compsci/events/cae-c-expansion/writing-and-communication-skills-tutoring/ ↑