Jennifer Carter

Kathryn Dean

Introduction

However, it is not uncommon for writing center tutors and administrators to situate factors that impact feelings of comfort and welcome in romanticized characteristics aimed at making our centers feel like home. As Elizabeth Boquet explains, directors consciously decided to “characterize the lab spaces as non-threatening (however specious) and to fill them with creature comforts—couches, plants, coffee pots, posters” to separate writing centers from the previous classification of “skill and drill labs” (as cited in Grutsch McKinney, 2005, p. 9). While this decision was ostensibly made with our students’ interests in mind, arranging our centers in ways that communicate this metaphor of home prescribes a universal design that assumes all of our students prefer working in spaces reminiscent of home, ignoring the possibility that these design choices were actually made more for the benefit of the staff than for our students. Grutsch McKinney (2005) even argues, “I’m afraid writing center professionals use these descriptions to show themselves as insiders in the field of writing centers—to show that they know the prescribed ideal for a writing center—than to really describe the feel of a space. To do that fairly requires critical readings” (p. 10). By interpreting how our students read the decisions and designs made in our centers, we can ascertain that our spaces actually make our students feel comfortable and welcomed. Better yet, we can have our students read our spaces critically and answer for themselves.

(Re)Reading Our Space[1]

Before we discuss our study and the feedback we received, we first want to take a moment to critically (re)read several characteristics of our writing center. In doing so, we will discuss both the intentions and limitations in some of our design choices.

In 2014, Georgia State’s Writing Studio—which operates within the English Department—joined several other departments in relocating to the former “Suntrust building.” Located at 25 Park Place in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, this building served as both a bank location and corporate offices for Suntrust Bank. Despite having some incredible views of downtown from our occupancy on the 24th floor, a residual corporate feel still permeates our space. Consider our door, for instance: solid, gray, and with no windows, the door that serves as the initial impression of our writing center looks exactly like every other door our students have encountered in the building. To counter this uniform characteristic and to help students find our center, we have added a sign to the door that welcomes students. Additionally, we choose to keep the door open, which actually creates a different problem. Surrounded by offices in a setting where voices carry, our writing center has received a fair share of noise complaints. However, closing our door doesn’t seem to be a viable option, since a closed door reads as uninviting, especially a door without windows.

Although we are unable to control the corporate feel and design of our space, we have attempted to make our space as welcoming as possible. Upon entering the writing center, and immediately to the right, we have placed our coffee/tea station, above which is an additional welcome sign. Around the corner from the coffee station, a collection of communal mugs—most of which were donated by former and current tutors—lines a supply cabinet. Additionally, although not in immediate view of students entering the center, our official “Welcome to the Writing Studio” sign hangs on the closest and most logical wall near the front desk.

Next to our front desk, we have two chairs and a couch. The inclusion of this furniture adheres to the intention of offering students who visit our center a place where they can sit comfortably. When students check in at the front desk, they are often advised to sit wherever they would like. Sometimes, students will take advantage of the couch or chairs, while other times, students will choose an empty table and ready themselves for their session. This lounge area is not off limits as a place to conduct a tutoring session; however, utilizing this area in this way is a rare occurrence. As it stands, this space reads as nothing more than a waiting area.

For several years, we attempted to liven the place up with a couple of plants that were brought over during the move. Unfortunately, either through neglect or an absence of direct sunlight (or both), we have failed to keep these plants alive. At one point in recent years, a couple of these plants (those that were not immediately trashed) were moved to the back window sill with the belief that they would eventually be nurtured back to life. This was not the case.

Hidden in the back corner, these plants became even more neglected and forgotten about. What is more unfortunate, however, is that this plant graveyard remained in view of one of the tables used for tutoring, putting the dead plants on display for all those who had a session in the back of the room. We feel it is important to note, however, that during the production of this article, these plants have since been thrown away and replaced with succulent terrariums.

Adding Student Voices

We decided that sending out a survey to the students who visit our center would be the best method to garner their feedback. In an email sent via WCOnline—filtered to include only students who had attended a session during the 2017-2018 academic year—we explained our center’s commitment to maintaining as welcoming a space as possible. Our research, then, served as an attempt to understand how welcoming our students considered the center. The survey was distributed during the summer semester in 2018 and ran for four weeks. Of the 1719 writing center patrons requested, we received a total of 91 responses.

Before focusing on our writing center specifically, we asked students what they thought made a space welcoming. Although this question requested answers for spaces in general, having read the email and survey introduction, students were aware of possible exigencies that prompted the initial question. Therefore, it is possible that the information they received before opting into the survey impacted how they answered this question. Rather than thinking about spaces broadly, students likely had framed the space to be a) a writing center and b) our writing center specifically.

Using a Likert scale, students were then asked to rate their overall feeling of welcome when visiting the Writing Studio. Additionally, students were asked to describe factors in the studio that made them feel welcome and unwelcome, including separate questions for the ways their tutors and other staff members contributed to these feelings. Finally, we asked students to indicate what they believe to be the purpose of the Writing Studio space. Collecting this qualitative data electronically, via a Google Form, allowed us to examine the responses, code them by emergent themes, and draw conclusions about our students’ perceptions on feeling welcomed in our writing center.

We had a relatively low response rate considering how many people we reached out to; however, the responses we received were substantial. We believe that analyzing these results can give us an idea of how students perceive our center generally, though we recognize the benefits of conducting a larger-scale study—perhaps even across different universities—to corroborate these results.

Survey Data and Results

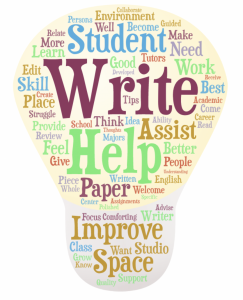

When asked what made a space welcoming, many students placed an emphasis on the people and ambience within a space, as illustrated in Figure 10. The prevalence of words like “people,” “friendly,” “open,” “talk,” “greet,” “invited,” and “warm” indicate to us that students find the presence of others a significant influence on how welcoming a space is. In their responses to this question, many students believed welcoming spaces were places where they could be themselves without fear of judgment, where people are friendly and inviting, and where the person feels like they’re wanted within the space.

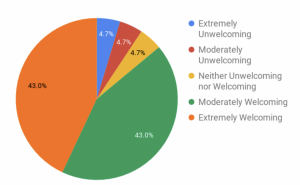

Students then rated how welcoming they found our center based on their experiences.

Though most students reported finding our center either “Moderately Welcoming” or “Extremely Welcoming,” we can’t ignore that results could have been impacted by the participants’ knowledge that tutors were collecting this data, even though their answers were anonymous. However, their answers to further questions helped us understand the nuances of those responses.

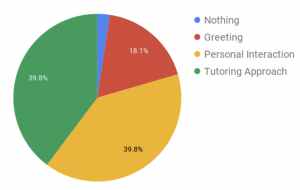

As students reported what their tutor did that they found welcoming, we noticed three substantial trends emerge: a greeting at the beginning of the session, particular tutoring strategies that they found helpful, and their personal interaction with their tutor. Some responses fell into more than one category.

Students were then asked to evaluate how welcoming the Writing Studio space is. We found that many students enjoyed the view from our studio, which has many windows and, since it is on the 24th floor of a central building, provides a great view of downtown Atlanta. Therefore, the view may also contribute to descriptions of the studio “space” as “open,” “natural,” and having “low” lights.

Other students focused on the workspace that the studio provides, citing “seating,” “chairs,” and “tables” as welcoming aspects of the studio. Finally, people played a large role in students’ perceptions of welcome within the Writing Studio. While some of the students mentioned their tutors, several responses referred to all staff members: “people,” “staff,” “receptionist,” “desk person” and “tutor.” Further, students who visited the Writing Studio when it was quiet reported this as a welcoming aspect of their experience.

When evaluating factors of the Writing Studio that are not welcoming, a large number of students responded that they did not feel they had adequate “time” for their sessions—either they felt rushed during their session or had tried to make a one-hour appointment that was then shortened to a half-hour appointment (a result of our policy that one-hour appointments are reserved for graduate students).

Many students also mentioned that they were intimidated by the Writing Studio’s location in a large building that also houses academic advising offices, which, as one student noted, makes approaching the center feel “pretty serious.” Finally, noise level was a complaint among students who visited when the center was loud. One student described the noise level in the Writing Studio as “unbelievable.” Students who described the noise level as unwelcoming mentioned that it distracted them from their tutoring session or the work they were doing.

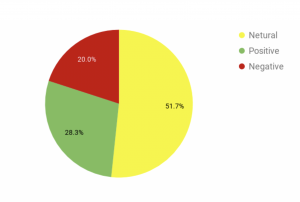

Though most students (51%) reported neutral experiences with tutors and staff they did not work with, some students identified interactions with other staff as having either positive or negative effects on their experiences within our space. The most common negative impact of other staff members was an increase in noise created by other conversations. Although some of the conversations were other sessions taking place, students found personal conversations among staff distracting.

The final question that we asked our students is what they considered the purpose of the writing center. Receiving input on this idea is important for several reasons. First, when students enter a space with expectations in mind, success or failure in meeting these expectations can set a particular tone that could impact the way students feel in that space. Meeting or exceeding expectations could positively impact feelings of welcome. Conversely, if a student’s expectations are not met, then they are likely to feel as though their needs are also not met, which could lead them to feel unwelcome. Additionally, having our students offer their understanding of the center’s purpose helps us to consider, more broadly, ways that we are or are not meeting their needs and could provide us insight into misperceptions that students have about our centers that we can readdress and/or remarket.

Overwhelmingly, students perceived the Writing Studio as a place to improve their writing skills in English. The prevalence of words such as “write,” “improve,” assist,” “better,” “learn,” “advise,” “edit,” “review,” and “skill,” indicate to us that students see our space as a resource to receive instruction to improve their writing. Additionally, these words tell us that students see the Writing Studio, at least to some extent, as a place to correct their mistakes. However, we also saw responses such as “grow,” “feel,” “comforting,” “collaborate,” “guided,” and “support,” which point to a more nurturing view of the space. In contrast to skills-focused words, these words indicate an understanding of the collaborative nature of writing tutoring and its existence outside the evaluative grading system. These words also indicate that this is a space where students and their feelings are supported and encouraged.

Conclusion

This study has only scratched the surface of what our students experience when they visit GSU’s Writing Studio. Our study, small and exploratory, had limitations in its design. We phrased our questions to help students generate broad, detailed responses about how they might find our center welcoming; however, students often seemed to read the suggested categories as possible options to answer with instead of prompts to respond to. Our questions, then, were more leading than we intended, and the answers we received were more about the categories we provided rather than a truly open-ended response. Additionally, we do not know the gender, race, or educational level of our respondents. We could improve our study by inviting students to share their experiences in interviews or focus groups. Conducting interviews or focus groups would allow us to have a conversation with our students about what they find welcoming and unwelcoming in the Writing Studio. We could also obtain demographic information currently missing from our study to aid us as we continue to look for ways to welcome all our students.

Our study has also raised questions about what, exactly, students expect from the Writing Studio. As we saw in our students’ responses to our question about the purpose of our space, students see our Writing Studio as a place where they can not only build their skills, but also where their ideas can be supported. However, there are some aspects of our studio as it functions currently that are unwelcoming to students. If there are many tutors in the writing center having loud, unrelated conversations, students find this distracting. Indeed, even though our Writing Studio serves as a socialization hub for many of our tutors, the space is small, and loud, exclusive conversations can have an alienating effect on those who visit our center. Therefore, we must consider how best to strike a balance between building community as tutors and building community with the students who come to us.

As we analyzed this data, we wondered whether we should try to make our center more “homey,” or if we should focus on other ways to make our center welcoming. Based on the voices of our students and their experiences in the Writing Studio, what can we change about our daily practice to make our students feel more welcome? Personal interactions have a lasting impact on students’ perceptions of the studio, as they were a consistent theme in our data. Although interactions with other staff members do not always affect a student’s experience in the Writing Studio, when they do, it is memorable to the student. Several respondents went out of their way to specify that one bad experience was not characteristic of their typical visits to the Writing Studio; however, those bad experiences clearly affected them enough to end up in their responses. When a student was ignored or treated with frustration by a staff member in the studio, that experience stuck. Struggling to be heard in a loud room or feeling like their tutor was distracted during their session was something that stood out to our survey respondents.

For instance, tutors who feel comfortable in our space may not notice the loud conversations that may distract a student. While our perception of the environment in the studio may be that it is a busy place full of people with great ideas, a student might see this as a distracting environment where they cannot concentrate. Finally, our assumption that people know what to do when they enter our space does not have a base in reality; many students reported feeling ignored if they were not greeted soon after entering our space.

Author Biographies

Jennifer Carter is a doctoral student in the Rhetoric and Composition program at Georgia State University. She worked as a tutor in the Writing Studio for five years and as the research coordinator for two years. Her current research explores the parallels of the performativity of identity and writing within different spaces. In her free time, she immerses herself in as much improv as possible, taking improv classes and attending/volunteering at various shows.

Kathryn Dean is a MA student at Georgia State University. She has worked as a tutor in the Writing Studio there since 2016. She has also served as the coordinator for the Center for Writing and Speaking at Agnes Scott College, where she received her undergraduate degree. Her current research joins her interests in digital rhetoric, user experience, and writing center studies, focusing on how to train tutors to work in online environments.

References

Boquet, E. H. (2002). Noise from the writing center. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Herrmann, J. (2017). Brave/r spaces vs. safe spaces for LGBTQ+ in the writing center: Theory and practice at the University of Kansas. The Peer Review, 1(1). Retrieved from http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/braver-spaces-vs-safe-spaces-for-lgbtq-in-the-writing-center-theory-and-practice-at-the-university-of-kansas/

Jacobs, R. (2018, February 5). What’s wrong with writing centers. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/What-s-Wrong-With-Writing/242414

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan: Utah State University Press.

McKinney, J. G. (2005). Leaving home sweet home: Towards critical readings of writing center spaces. The Writing Center Journal, 25(2), 6-20.

Martini, R.H., & Webster, T. (2017). Writing centers as brave/r spaces: A special issue introduction. The Peer Review, 1(1). Retrieved from http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/writing-centers-as-braver-spaces-a-special-issue-introduction/

Mendez Newman, B., & Gonzalez, R. R. (2017). Narratives of student writer and writing center partnering: Reconstructing spaces of academic literacy. The Peer Review, 1(1). Retrieved from http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/narratives-of-student-writer-and-writing-center-partnering-reconstructing-spaces-of-academic-literacy/

Oweidat, L. & McDermott, L. (2017). Neither brave nor safe: Interventions in empathy for tutor training. The Peer Review, 1(1). Retrieved from http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/neither-brave-nor-safe-interventions-in-empathy-for-tutor-training/

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions…decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147-171.

Salem, L. (2018, February 9). Writing-center researcher says views were mischaracterized. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/letters/writing-center-researcher-says-views-were-mischaracterized/

- All photographs taken by the authors of their writing center space unless otherwise noted. ↑