Leia Eller

Olivia Wood

In our undergraduate training course, like many others, consultants-to-be learn about the role of the writing center as an institutional middle-ground, a liminal space between teachers and students, the university and the individuals within it. University-sponsored “peer” tutoring, of course, depends on situating ourselves as such. However, writing center practitioners’ view of ourselves and our work, and the image we present to our consultants-in-training, can be very different from the preconceived images that incoming writers have of the writing center. Some are nervous, scared we will “tear apart” their papers. Others are skeptical, unsure of how an undergraduate consultant could possibly help them with their writing. Some resent a required visit; others look forward to their sessions. Before a writer has actually visited a writing center for a consultation, how can we communicate to them the nature of what we do? If a writer feels nervous or out of place, how do we reassure them as quickly as possible, before they even interact with a writing center employee? How does our local context, as a liberal-leaning university in a liberal-leaning county in a predominantly conservative state impact these dynamics? In this article, we will describe the interventions of “welcome” that we are currently implementing in our writing center at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) and the theoretical considerations behind our choices. While we have tailored our interventions to the needs of our specific institution and situation, we share our experiments with welcome in hopes that other writing center practitioners can adapt our methods to the needs of their own centers.

We are both graduate assistants who worked in the UNCG Writing Center as undergraduate consultants before beginning our master’s degrees. In addition to consulting, our assistantships include other duties to support the work of the center. Leia serves as the Resources Coordinator and is responsible for maintaining and updating handouts and handbooks, decorating the writing center, and supporting employees and writers with additional resources, such as writing center stickers and T-shirts, writing implements, etc. Olivia serves as the Social Media Coordinator and is responsible for updating the center’s Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr feeds. Together, we are largely responsible for the first impressions writers receive of the center, physical and digital.[1] Because we are both acutely aware of this responsibility, we have been extremely mindful of our university’s specific cultural history, both past and present.

About Our Center

Our university has a single writing center, which serves all populations within the institution, rather than having separate writing centers for undergraduate and graduate students, as some universities do. We also welcome consultations with faculty and staff, as well as students from the early college affiliated with UNCG, although these types are rare. UNCG is also home to one site for the “Interlink” program, which provides intensive English instruction to students who have recently moved to the United States and for whom English is a second language. Many Interlink students have offers of admission from American universities contingent upon graduating from Interlink, and may already have bachelor’s degrees from their home countries. Judging by the writers we have worked with in the center across several years, it seems that a large portion of Interlink students are from countries in the Middle East, a region that suffers from many negative stereotypes and a contentious political climate in contemporary American discourse. In the Spring of 2018, 73% of our writing consultation sessions were with undergraduate writers, 15% with graduate writers, and 11% with Interlink writers. Approximately one quarter of all Spring 2018 sessions were with writers who indicated that English is not their first language.

While our center does not collect data on race, gender, or other demographics, the university as a whole is slightly over 50% white, with black students comprising the second largest ethnic or racial group. Additionally, two thirds of our undergraduate population self-identifies as female, reflecting our history as the Women’s College of North Carolina, although we became co-ed in 1964. UNCG is the most racially diverse historically-white school in the UNC system. Based on data from the American College Health Assessment, our campus Office of Intercultural Engagement estimates that as many as 27% of our undergraduate students may identify as non-heterosexual, and as many as 11% may identify as non-cisgender (Kimball, 2018). The university has a colloquial reputation as “UNC-Gay,” which dates back to the 1970s. However, North Carolina’s “Amendment One” to the state constitution defining marriage as explicitly between one man and one woman in 2012 and the more recent “bathroom bill” (HB2) attempting to exclude trans people from public bathrooms certainly color the local experience—and anxieties— of being LGBTQ+. Our personal experiences as undergraduates and later as graduate students on campus seem to indicate that overall, the campus leans left-of-center politically; however, left-wing[2] students typically feel restricted by our location in the Bible Belt, and right-wing students typically feel restricted by the liberal leanings of both Guilford County and the university itself. Therefore, our local campus culture requires us to engage in a complex balancing act as we weigh the needs and comfort of the distinct student populations we serve in our work as Resources Coordinator and Social Media Coordinator for our writing center.

Welcoming Writers in the Face-to-Face Center

In taking on the role of Resources Coordinator, Leia eagerly accepted a position that had few officially outlined duties beyond keeping handouts available and making copies when needed. She was given free reign by our Writing Center Director to implement any organizational projects she chose, as the Center’s resources needed a bit of tender loving care. Beyond managing the physical resources of the center, such as reference books and consultation sheets, Leia began to think seriously about the number one resource of any university writing center: the writers who come to us for assistance. Cognizant of the fact that writers are the reason for any writing center’s existence, Leia recalled Louis Althusser’s claim that people are “given a sense of being individual subjects by being addressed in certain ways by (through) our own culture” (Fiske, 2017), and in this way, “ideology hails or interpellates individuals as subjects” (Althusser, 2010). With this framework in mind, she began to explore how she could hail writers from marginalized groups before any staff member ever spoke to them, making them feel immediately welcome and at ease when they entered the center. How exactly could the term ‘welcome’ be best defined and applied to our center? After an exhaustive search, Leia found a definition of ‘welcome’ that she felt encompassed her ethos: “to meet, receive, or acknowledge in a specified way” (Collins, 2018). How, Leia wondered, could our center work to create an instantly welcoming space, one which projected warmth and inclusivity, while simultaneously acknowledging the reality of our varied student population?

This question was extremely important to Leia, as our writing center staff does not currently reflect the true diversity of UNCG’s student population. For example, as previously mentioned, though our campus population is just over 50% white, the writing center staff is approximately 95% white, employing only a handful of consultants of color. Leia found this problematic, as students of color constitute a large portion of the student population we serve. When Olivia returned from the 2017 IWCA Conference, she had a unique perspective on this particular conundrum, as she was able to attend the keynote address by Neisha-Anne Green, an author of color. In her talk, Green discussed the whiteness of writing center spaces and how after learning how to be a good consultant and writing center administrator, she also had to unlearn the colonizing ideologies of writing center work so she could do her job without sidelining other aspects of her identity. Similarly, Sarah Ahmed (2017) explains in Living a Feminist Life how institutional spaces are designed for “use” by particular kinds of people, and people who do not fit those strict parameters can feel “used up” by the effort required to fit themselves into that space. If our writing center is shaped for use by white, cis, straight (able-bodied, upper middle class, etc.) writers and consultants, how could we alter its shape to make its use less taxing for other writers?

Furthermore, although roughly a quarter of our staff identifies as non-heterosexual, it is difficult to properly publicize this type of personal information. Whether and how consultants choose to out themselves to writers, or present their identities in other ways, is an intensely personal choice that can have professional ramifications (Rose, 2016). Additionally, outward signifiers that may read as potentially queer to some—such as gender nonconforming dress—may not be interpreted as such by writers, and queer consultants’ self-presentation may simply not line up with stereotypically “queer” self-presentation. This combination of factors prompted Leia to investigate what needed to be done in order for the writing center to be officially established as a UNCG “Safe Zone.” The Safe Zone Program originates from the institution’s Office of Intercultural Engagement, and aims to engage in “a deep and meaningful exploration of aspects of LGBTQ+ identity.” Consider this an information-packed, build-your-own-adventure rest area on your journey of continuing education around gender, sexuality, and creating a more inclusive campus” (Harris, 2017).

Leia’s new goal as Resources Coordinator became figuring out how to immediately welcome and put at ease any student who walked through the door of the writing center, especially those groups historically marginalized due to their race, nationality, ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Ultimately, Leia wanted to provide an environment in which all writers felt safe to express themselves freely while also feeling safe from judgement, ridicule, or rejection. In order to achieve this goal, Leia started by implementing small, unobtrusive changes to the appearance of the cubicles in which consultations take place.

She began by searching for literary quotations from female writers and writers of color, such as 2014 Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani girl shot in October 2009 by Taliban insurgents for championing women’s education (see Figure 1), and 1993 Nobel Peace Prize winner, Nelson Mandela, who spent nearly 30 years in prison for his efforts to end apartheid in South Africa. Slowly, more faces and quotes followed, including authors such as Oscar Wilde, Alison Bechdel, and Leslie Fineberg. However, Leia was aware that some of the students, especially incoming freshmen, might not recognize Wilde, Bechdel, or Fineberg as queer authors. Therefore, she began exploring the possibility of displaying rainbow-colored writing instruments, such as a quill (see Figure 2), stacks of books, and ink overflowing from an inkpot. As her intention was to attempt to make every writer feel welcomed, Leia also made certain to represent the white, hetero, cis-gendered population as well, including quotes from writers such as Stephen King and Tom Clancy. While Leia is happy to report positive reactions from both student writers and fellow consultants to the changes she has introduced, she realizes that the job of highlighting marginalized writers will continue to be a work-in-progress.

Welcoming Writers in the Online Center

In our writing center’s social media presence, Olivia implemented two major welcoming initiatives during her time as the Social Media Coordinator (2015-2018) and began to develop a more general—and subtle—social media strategy during the 2017-2018 academic year, which her successor is continuing to develop. The first initiative explicitly engaged with current political events as a rhetorical performance for the benefit of immigrants and ESOL (English as a Subsequent Other Language) writers. The second initiative targeted LGBTQ+ writers by featuring LGBTQ+ writers on our social media accounts during “Pride Month at UNCG” and changing the phrasing of our online sign-in form.

The first major social media initiative Olivia implemented was to directly engage with political events as they pertain to the needs of our writers. Even among Americans, the South is stereotyped for its bigotry, and 2016 electoral maps did even more to associate us with anti-immigrant, anti-Hispanic, and anti-Muslim opinions. Writers who belong to these groups likely enter the center for the first time without knowing if the space will be welcoming, accepting, or open to their identities. Is the writing center safe for them? How can they know? After the election, Olivia published the following Facebook post with approval from our Director:

The University Writing Center at UNCG would like to formally state that in this post-election time fraught with very strong feelings, we welcome papers on all topics spanning all points of view. Our job is to discuss your work with you so that you may communicate more effectively.

While all of the University Writing Center’s individual staff members do have their own dearly-held political opinions, the Center itself takes the position of privileging freedom of speech and expression, and we, the consultants and desk managers, are committed to upholding that value while we are at work.

Furthermore, we ask that visiting writers uphold this value as well while they are in the Center and be cognizant and respectful of the fact that the people around them–staff and fellow writers alike– may have different perspectives and be undergoing different emotional experiences at this time. Please help us in keeping the Center a safe space for all people to work on their writing.

Later on, the post was adapted to refer to all three multiliteracy centers and posted on the door that our writing center shares with the University Speaking Center.

In retrospect, we are torn about the efficacy of this post, especially given the ongoing use of “free speech” as a favored phrase and argument of neo-Nazis. Officially, we positioned ourselves as, institutionally, equally supportive of all viewpoints. Again, in retrospect, this phrasing calls to mind Trump’s reference to violence “on both sides” of the neo-Nazi demonstration at Charlottesville. Unofficially, we are allowed some wiggle-room in challenging oppressive viewpoints in our sessions—as long as we keep the conversation focused on the writing and make sure the writer continues to feel comfortable in the Center. But again, how is anyone outside the writing center to know that?

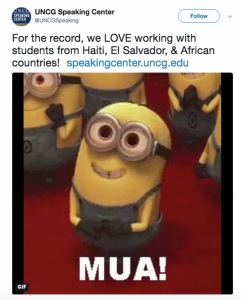

After news broke regarding Donald Trump’s alleged comments regarding certain “shithole” countries[3], our University Speaking Center tweeted, “For the record, we LOVE working with students from Haiti, El Salvador, & African countries!” (@UNCGSpeaking). The tweet also included a GIF of a Minion[4] blowing a kiss (see Figure 3). We retweeted this post with the added comment, “We love it too!” (@UNCGWritingCtr). We have not received feedback or other kinds of reactions to either of these political messages except for two Twitter “likes”: one from a UNCG student and one from the UNCG Dean of Students account. However, we are also uncertain how many writers and other members of the campus community actually saw either post, given the limited engagement our social media posts tend to receive. Additionally, it seems unlikely that many visitors to the writing center or speaking center would take the time to pause in the doorway to read a lengthy post written in small type. Olivia will not be able to continue improving our political engagement as a writing center all by herself, as she is leaving UNC-Greensboro to begin a PhD program elsewhere, but she has discussed the shortcomings of this initiative and potential future goals with the consultant who will be taking over her responsibilities as Social Media Coordinator.

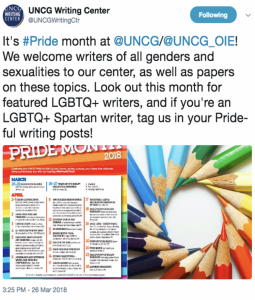

The second social media initiative, directed at LGBTQ+ writers, has proven more successful. In Spring 2017, a trans undergraduate friend texted Olivia to ask if it would be safe to bring a paper about trans issues that outed himself into the writing center. This initiative was designed to signal “welcome” to writers such as her friend ahead of time, so that questions like his would no longer be necessary. Accordingly, our sign-in form has also been changed to add a parenthetical explaining that we do not need the writer’s legal first name—only what they want us to call them. Olivia leveraged Leia’s quote posters for LGBTQ+ writers by reposting the writers’ faces and associated quotes on the writing center’s Facebook and Twitter pages along with additional biographical information about the writers, presenting this series of featured writers as part of “Pride Month at UNCG,” a campus-wide event. At the end of March, when the campus-wide programming began, Olivia shared a post on Facebook and Twitter, adapted slightly for each platform, shown in Figure 4.

This tweet received 5 retweets and 10 likes, which is much higher than our typical user engagement. Analytics for our Facebook page show that the corresponding post on Facebook reached 91 viewers (much higher than our typical reach of 59 viewers for photo posts) and received six clicks and four reactions (exactly average for photo posts).

After featuring two of the LGBTQ+ writers Leia had already made posters to place around the Center, and Olivia sent out an email to the staff listserv asking if any LGBTQ+ staff members were interested in being featured themselves.[5] Two staff members volunteered, and Olivia asked them to email her whatever photos or text about themselves they were comfortable with her sharing on the Center’s social media. Only one of these two staff members ended up writing a post, although the other’s hesitation was related to what she wanted to say about herself as a writer rather than as an LGBTQ+ person. The post is shown in Figure 5, sans the consultant’s photo and name, which we omitted from the screenshot.

This post reached an audience of 55 people (slightly below average for photo posts) and received five clicks and six reactions (slightly higher than average for photo posts). In the future, we intend to implement a similar post series featuring writers from other marginalized groups, much like the diversity of Leia’s in-center posters.

Overall, we have both been encouraged by the positive reactions of writers, staff, and the administrative team. We are excited by the quantitative data indicating a higher-than-average response to the initial LGBTQ+ Facebook post highlighting UNCG’s Pride Month celebrations. Additionally, the traffic created from the personal post from one of our LGBTQ+ consultants was also encouraging. Unfortunately, Leia does not have quantitative data concerning writers’ reactions to the changes implemented in the physical writing center space, though anecdotal evidence from individual sessions indicates that our student population is excited by the center’s “new look.”

However, Leia continues her efforts to highlight marginalized groups and is currently focused on better serving Latinx writers and writers with disabilities, as well as continuing the writing center’s efforts to better support LGBTQ+ writers. Since the initial submission of this article to The Peer Review, several new developments have occurred. Leia was able to create a “Kids’ Korner” in an attempt to make our space more inviting to students with children. The “Korner” currently includes lap-desks, coloring books, and a few literary selections by Dr. Seuss and Beatrix Potter, and Leia is always looking to make improvements. Furthermore, after a bit of detective work via UNCG’s website, she was able to determine that receiving official designation as a Safe Zone space would require attendance at a three-session workshop by a graduate assistant. The workshop sessions covered Safe Zone 1.0, Safe Zone 2.0, and Trans Zone, and both she and another graduate student were able to attend these sessions early in the fall semester. Therefore, the UNCG Writing Center is now, officially, a campus Safe Zone. This fact is clearly demarcated to all students, faculty, and staff via UNCG Safe Zone Stickers, which have been conspicuously placed in the hall above the official UNCG designated sign for the Writing Center, as well as immediately inside our front door (see Figure 6).

As Olivia graduated from her master’s program in May 2018 and left to pursue her PhD at the CUNY Graduate Center, Leia continues her work at UNCG in her second year as the Writing Center’s Resources Coordinator, and we remain in close contact with one another. While exact numbers are not yet available, we are able to make several observations concerning student participation at the UNCG Writing Center for the Fall 2018 semester. First in the more than four years Leia has worked at the center, Fall 2018 has been the first semester in which the Writing Center had fully booked all appointment times for our opening week prior to opening day. Moreover, our appointment slots continue to remain fully booked, and our staff of more than 40 consultants is constantly working with drop-in writers either face to face or online. Furthermore, while it is the policy of the UNCG Writing Center that consultation sessions run for 60 minutes, we have been regularly forced to cut that time to 30 minutes per session because we have such high traffic, which is very unusual for this time of year.

Again, while it is too early to offer quantitative data, we both firmly believe that through the simple act of focusing on implementing welcoming strategies, both physical and digital, the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro has gained a great deal. While metrics are great, especially for funding and budgets, Olivia and Leia worked as a team to construct a space in which all members of our diverse student population would feel accepted, appreciated, and included in our center’s vision of our future. It is our hope that other writing centers can and will implement strategies similar to those we utilized, reaching out to embrace and welcome marginalized writers based on the needs of their own local communities. During a 2018 IWCA panel led by our colleagues at Virginia Tec, an audience member Olivia met said, “Tolerance is being allowed at the dance, and inclusivity is being asked to dance.” Who does your writing center “ask to dance,” and who is merely allowed to be there? How will different populations at your writing center know it is a welcoming environment for them, if they have never been there before? How do you signal to the broader campus community what you already know about yourselves? While we cannot yet validate the claim that our “welcoming” work is partly responsible for the increased traffic currently gracing the UNCG Writing Center, we both believe that it played a meaningful part.

Author Biographies

Olivia Wood is a composition instructor at New Jersey City University and PhD student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. She holds an MA in English from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG) and a BA in English and Anthropology, also from UNCG. Her responsibilities over her 4 years at the UNCG Writing Center included working as a consultant, desk manager, shift manager, social media coordinator, workshop leader, and teaching assistant. Her research interests include queer rhetorics, digital rhetoric, critical pedagogy, and Virginia Woolf, and she serves as part of the Digital Content Team for the International Writing Centers Association.

Originally from Dayton, Ohio, Leia Eller completed her Bachelor’s Degree in 2017 at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, where she is currently working towards completing her Master’s Degree in English. During her time at UNCG, she has worked in the writing center as a consultant, shift manager, and Resources Coordinator. After graduation, she plans to pursue a career teaching at a community college, encouraging her students to continue their education at 4-year institutions, just as she did.

References

@UNCGSpeaking. (2018, January 12). For the record, we LOVE working with students from Haiti, El Salvador, & African countries! Message posted to http://twitter.com/ UNCG Speaking/status/951806229340393472

@UNCGWritingCtr. (2018, March 26). We welcome writers of all genders and sexualities to our center, as well as papers on these topics. Look out this month for featured lgbtq+ writers, and if you’re an lgbtq+ spartan writer, tag us in your pride-ful writing posts! Message posted to https://twitter.com/UNCGWritingCtr/status/978367369025347586

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Althusser, L. (2010). Ideology and ideological state apparatuses (notes towards an investigation). A. Sharma & A. Gupta (Eds.), The Anthropology of the State: A Reader (pp. 86-111). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Benson, A. (2014). ‘We also offer online services at interpellation.edu’: Althusserian hails and online writing centers. Southern Discourse in the Center: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation,9 (1), 11-25.

Fiske, J. (2017). Culture, ideology, and interpellation. In J. Rivkin & M. Ryan (Eds.), Literary theory: An anthology (pp. 1268-1273). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Entry for ‘welcome’. (2018). In Collins Dictionary: Definition, Thesaurus and Translations. New York, NY: Harper Collins. Retrieved April 12, 2018, from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/.

Green, N. (2018). “Moving beyond alright: And the emotional toll of this, my life matters too, in the writing center work.” Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15-34.

Harris, M. D. (2017, May 31). Safe Zone Summit at UNCG. Retrieved May 12, 2018, from https://uc.uncg.edu/prod/cweekly/2017/05/31/safe-zone-summit-uncg/

Kimball, E. (2018, May 10). Message to the authors [Email to the author].

Rose, R. (2016). Queering the writing center: Shame, attraction, and gay male identity (Unpublished master’s thesis). East Carolina University.

- While the design of our center’s website also plays a role in writers’ first impressions, the website is currently only updated with informational changes to existing website features like hours of operation and consultant names, rather than design changes. For information on the rhetorical design choices of the UNCG Writing Center website, please refer to Alan Benson’s article “‘We Also Offer Online Services at Interpellation.edu’: Althusserian Hails and Online Writing Centers,” published in the Fall 2014 issue of Southern Discourse in the Center: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation. ↑

- In this article, “left-wing” is used to refer to all political views left-of-center, ranging from mainstream Democrats to communists. We do not use it to refer to “the Left,” which typically designates socialists, communists, and others who align themselves further along the political spectrum. ↑

- https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/11/politics/immigrants-shithole-countries-trump/index.html ↑

- “Minion” here refers to one of the small yellow creatures in the film Despicable Me and its sequels. ↑

- In composing this email, Olivia was careful to stress the voluntary nature of being featured and potential risks to volunteering, and she addressed the email to the entire staff instead of only staff members she knew were LGBTQ+. She offered a list of options that such a post could include (text only, a picture, writing advice, writing quotes, etc.) and invited potential volunteers to choose whatever they felt most comfortable with. As an alternative, she also invited staff members to suggest their favorite LGBTQ+ authors to be featured instead. ↑