Sydney Fleck

August 28, 2015

Marilee Brooks-Gillies is our W496, Writing Center Theory and Practice, professor and the director of the IUPUI University Writing Center (UWC).

She’s hilarious, and brilliant, and passionate about Writing Centers – which I’m learning are actual things of which people have written about, studied, and made careers of.

Before class, we read Stephen North’s “The Idea of a Writing Center” and “Revisiting the Idea of a Writing Center.”

Apparently, Writing Centers are for fitting into, observing, and participating in “[the] solo ritual of writing . . . Rather than being fearful of disturbing the ‘ritual’ of composing, [we] observe it and are charged to change it . . . in ways that will leave the ‘ritual’ itself forever altered” (North, 1984, p. 439).

I don’t really know what any of that means but Marilee makes me want to learn. She makes me excited about this world of writing centers.

Terry is the oldest person in our class and the only person of color. He’s black. And apparently he’s here because a professor in the Africana Department said the UWC is not “for” black students.

Terry has taken issue with that.

“It is better to change something from the inside,” he says.

And so, here he is.

Terry makes me uncomfortable. I cringe when he speaks. His words are honest and biting.

I want Terry to stop talking so much.

September, 2015

In a session I observe as a peer consultant and an international student work on a piece about analyzing advertisements. The focus of their session is word choice; the consultant spends a lot of time saying, “No, I would use [insert word] there, instead.”

But she’s not asking the writer why she chose the words she did and she’s not explaining the words she’s telling her to use now. She’s just pointing and replacing.

Something as simple as word choice could be an opportunity to understand a student’s culture and writing process. But between this consultant and writer – there is no negotiation. Paulo Freire (1970) tells us that teachers must have dialogue – that it is “through dialogue . . . [that] the teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students . . . They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow” (p. 80). Instead of dialogue, though, I see that “The teacher teaches and the students are taught; the teacher knows everything and the students know nothing” (p. 73).

I know we’re not teachers but we’re people with knowledge or, at least, with words and people listen to our words.

So we must be careful with how we use them and how we impose them on others.

November, 2015

I’ve finally realized that Terry makes me uncomfortable because he’s right, and because I need to hear what he has to say.

Once, in class, he was talking about the UWC’s need to embrace other cultures and peoples. He asked one of our classmates: “How often do you spend time with people who are different from you, on purpose?”

I’ve been asking myself the same question and I’m embarrassed by my answer.

I’ve started praying that I can be more like Terry. I pray that I can learn to say what I think, and that I can have something worth saying.

Terry is at the UWC to change things and, to my discomfort, he’s been changing me, too.

December, 2015

The semester is coming to a close and I can’t wait to start working at the UWC. I’ve learned so much and I’m excited to start talking to people about writing. I’m excited to have a job that matters.

We’re given access to the google doc that allows us to sign up for our hours. I wait for Terry to make his schedule so I can make sure I have hours with him. I want to be able to talk to him more.

I want to keep listening.

January, 2016

Terry has started calling me one of his favorite people.

After our most recent staff meeting I told Terry I thought he was cool.

He told me, “Sydney, you’re cool. And do you know what makes someone cool? They don’t realize they’re cool and they inspire the people around them to be cool too.”

I don’t think I’m cool. And I don’t think I could actually be one of Terry’s favorite people, but I also don’t think Terry would ever say something he doesn’t mean so I’m trying to believe him.

February 26, 2016

St. Hermione is a fake patron saint of writing centers that a crew of consultants made up some years ago so they wouldn’t have to celebrate Valentine’s Day. Instead, we celebrate St. Hermione’s Day.

We all eat food and break into groups to talk about Nancy Grimm’s Good Intentions and our identity as a writing center.

I tell my group how thankful I am that we’re not celebrating Valentine’s Day, since I’m the only one in my family without a significant other. I feel grateful to have people around me that care about writing and will write fun stories about a fake patron saint.

I love my job. I love these people.

I love the Writing Center.

February 29, 2016

It’s a Monday morning, and I get ready for work in that mindset. It’s like grungy-high school Sydney rolled out of bed; I put on ripped jeans with leggings, a ripped band t-shirt, and a huge (also ripped) sweatshirt.

When I walk in the door to the Writing Center, Terry is sitting at the front desk. Immediately he points at me and says, “Sydney, I need to talk to you.”

Naturally, I assume I’ve done or said something wrong. Maybe I said something culturally insensitive or racist at the party on Friday. Terry would tell me. And I would want him to.

But I hope it’s not that.

“Get settled and then come back so I can talk to you.”

I put my book-bag and coat down in a corner then pull up a chair next to Terry.

“Sydney… on Friday you said that you’re single. Is this true?”

I have to think back to a few days ago and the joke I made.

After I affirm that I am, indeed, single, Terry continues:

“I told my wife what you said and how surprised I am because you’re such a nice girl and she said, ‘Well have you introduced her to our son?’ And I thought that was such a great idea. So he’ll be here at twelve.”

Twelve is fifteen minutes away. I woke up thinking I had no one to impress today. One of the coolest people I know is setting me up with his son.

Awesome.

I have a desk shift and Terry has a consultation, which starts on the hour. His son still hasn’t showed up so he tells me to just talk to him when he comes in. “You’ll know him when you see him – he’s tall, dark, and handsome.”

About fifteen minutes later, Terry’s son is standing in our doorway, proving his father right: I know him when I see him and he is dark and very handsome (although I wouldn’t think of him as tall).

I’m about to pretend I don’t know who he is or why he’s here and open my mouth to say, “Hi, can I help you?” when Terry excuses himself from his session to greet his dark and handsome son. He throws his arm around his shoulder and walks him around the Center, introducing him to everyone we work with.

When they come back to me, Terry grabs my hand and says, “And, Brandon, this is my very good friend Sydney.” He looks at us both with a grin and adds, “Now you two get acquainted” before going back to his session.

Terry’s son laughs a bit and pulls up a chair next to me at the front desk.

We start talking and, even though I’m self-conscious and surprised by how ridiculous this situation is, it’s nice.

We talk about his work as a computer programmer and my work at the Writing Center. We talk about the churches we go to, the ministries we’re involved in, our favorite things to study about God, kids, travelling, our families…

I’m kind of disappointed when it’s nearly 1:00 and Terry walks over to usher his son away.

“He’s taking me to lunch!” he announces to me as he’s nudging Brandon out of his chair, and out of our conversation.

Brandon says that it was nice to meet me and to have a nice day as he’s walking out the door. Terry’s just behind him and, before he leaves, he gives me a hug and exclaims, “We’ll talk later!”

I laugh and walk over to my client, ready for this day to assume some kind of normalcy and trying not to feel too let down that Brandon didn’t ask for my number.

“My son thanked me for introducing him to you,” Terry tells me when I work with him next.

I’m blushing. “Yeah, it was really nice to meet him.”

Terry is nodding, clearly happy with himself. “And…he said he was nervous to ask for your number. So, if you want, I could give it to him.”

I’m trying not to sound too eager when I say, “Yeah, that’d be nice.”

Terry claps his hands together, “Great!” He takes out his phone to add my number then asks, “Do you think you could enter it and send it to him? I’m really not good with technology.”

“Of course.” I take his phone, enter my number, and then open up a text message to send it to Brandon.

He takes the phone back from me, hits send, and says, “Excellent, now he has it.”

March, 2016

I’m taking “Introduction to Language Use” and we have a final project that’s a twenty minute presentation on a topic of our choice. I’ve decided to examine the notion of “Standard” English” because I’m still thinking about Peter Elbow’s “Vernacular Englishes in the Writing Classroom?” that I read in W496. In the Center, I’m still wrestling with the balance between helping students use the dialect they’re most comfortable with and helping students use Standard English so they can graduate and get jobs.

For the assignment, I read “The Students’ Right to Their Own Language” and learn of the connection between identity and language: “Since dialect is not separate from culture, but an intrinsic part of it, accepting a new dialect means accepting a new culture; rejecting one’s native dialect is to some extent a rejection of one’s culture” (CCC, 1974, p. 8).

This seems so obvious – why have I never realized it before?

I read “Academic Discourse and the Formation of an Academic Identity: Minority College Students and the Hidden Curriculum” by White and Lowenthal (2011) and realize that not everyone starts on the same “page” when they come to college: “Schools value and privilege specific forms of literacy; K-12 and college-level educators tend to expect all students, regardless of their culture or background, to be experienced in the specific, ritualized, and formal form of discourse/literacy common to most academic environments” (p. 16).

I realize how white I am, to have the privilege to have grown up with and learned “Standard English.”

I’m embarrassed. I’m annoyed. I’m impassioned. No one has ever told me these things. I’m glad I’m learning now.

March 12, 2016

Grandma and Grandfather host dinners at least once a month to bring our family together. We’ve gathered in celebration of St. Patrick’s Day and are all talking amongst ourselves while we’re eating.

I make a passing comment that I want to learn to dance and my dad says, from the other end of the table, “Maybe Brandon can teach you!”

Brandon and I have only been texting for a few weeks. I hardly know him.

“Dad, stop. That’s like…stereotyping.”

My older brother, who is sitting across from me, looks up from his plate, confused. “Why would that be stereotyping?”

“Because he’s black.”

His response is nearly instant, “How black is he?”

I don’t know what to say and I smile, hoping he’s joking. “What do you mean? Are you racist?”

His girlfriend, at his side, laughs and says, “Aww, that’s so cute and innocent” like I’m ridiculous for being surprised.

March 20, 2016

Brandon and I are at Starbucks – it’s the fourth time we’ve hung out since our first meeting at the Writing Center, and I can’t tell if we’re just talking or…like…talking. So I ask.

“I know this is kind of weird,” I say, timidly. “But…like….”

“You can ask me anything; I don’t mind,” he assures me.

I laugh because I’m uncomfortable and he doesn’t know what he’s approving.

“Well, I was wondering if like… we’re just hanging out or are we going on dates?”

He’s obviously taken aback. “Uh… why would you think we’re going on dates?”

“I mean… just because of how your dad introduced us.”

He raises his eyebrows, “What do you mean?”

I tell him about walking in that Monday morning and Terry making sure I’m single before telling me Brandon was coming in.

Brandon takes his glasses off and rubs the bridge of his nose, clearly surprised. He laughs and says, “All he told me was he wanted me to take him to lunch and that he wanted me to meet his friend at the Writing Center.” He shakes his head and replaces his glasses on his face. “Well, now it makes sense why you might think these are dates.” We both laugh and he says, “It’s not that I don’t want to date you or anything but, I don’t really know you.”

“No, I’m glad,” I say in complete agreement. “Really, I think it’s silly to date someone you’re not friends with first.”

“Yeah, me too.”

“So, we’re just friends.”

“Yeah, friends.”

We spend the next two hours together; he doesn’t talk much but he listens well. He’s intelligent and witty and so funny. His smile is wide and dazzling – I get distracted by it more than once in conversation. I leave grateful to have met him and looking forward to getting to know him better.

For my language use presentation, my PowerPoint is entitled “What the What is Standard English??? And why should we care?”

I provide the historical context of the notion of Standard English and make everyone watch a YouTube clip of David Crystal talking about dialects. I explain idiolects and the Sapir-Wharf theory. I talk about language and identity and power. And then I ask everyone to care about it.

I wish I could have more than twenty minutes. I wish I could explain more. I wish more people were in my class to listen to what I have to say.

I tell Marilee about my presentation because I’m still excited about it and I think it connects with our work in the Writing Center.

She’s excited, too, and she agrees. She even tells me I can do an independent study on it. Together, we work out a syllabus and I start reading even though I don’t technically have to until August.

March 29, 2016

Brandon meets me on campus and we spend the afternoon walking around downtown, laughing and talking the whole time.

Brandon meets me on campus and we spend the afternoon walking around downtown, laughing and talking the whole time.

Eventually, we find a perfect view of the sunset and sit down.

It’s cold outside so we sit close to one another. Our conversation lulls for a moment as we watch the sun dip lower down.

Finally, he breaks our silence. “So…there are some people in the world who are…” he searches for words and continues, “perfectly okay with there being black people in the world. But some people are not.” He hesitates a moment, gathering more words. “Not that we’re dating or anything, or that we’re going to date… But, what about your family? What would they think if you dated someone who was black?”

Immediately I hear the “How black is he” from dinner two weeks ago, and say after thinking for a moment, “Well, actually, my older brother is racist. He’s the only person in my family that I guess wouldn’t be okay with it.”

He’s quiet so I add, “I didn’t know until recently…”

“Oh? And how does it make you feel?”

I don’t know how to say everything I’m feeling so I just say, “Honestly, I’m just upset.”

“Why?” he prods.

“Because I like you – and I should be able to bring you around my family no matter what you look like.”

There’s silence between us. I want to apologize but I don’t know what to be sorry for. Instead I say, “If it makes you feel any better, my brother hates me because I’m a Christian.”

Brandon laughs. “So he’d hate me anyway, huh?”

April 9, 2016

Brandon’s become my friend so fast I can hardly believe it and I’m so grateful.

We’re at the Indiana State Museum because he’s never been and it’s one of my favorite museums in the country. We start at the first exhibit, a geographical history of the world, and of Indiana. We look at old rocks and talk about our views on Creationism and Evolution.

We find a giant globe that changes when you push a button to globes that were created in previous centuries.

We look at the 16th Century, it’s off looking but you can distinguish the continents. “I’d still be in Africa,” Brandon says, and points at the blob in the center. We both laugh a little bit.

Next we look at a 17th Century globe and Brandon says, “I probably still would have been in Africa…”

He switches it to the 18th Century. “Now I probably would have been in the U.S. but we definitely wouldn’t have talked.”

Neither of us is laughing now.

April 27, 2016

I’m learning that Standard English is a beast in the imagination of every professor, all of whom expect every student to know what their beast looks like. It is Lewis Carrol’s Jabberwocky, whiffling through the tulgey wood of Academia, burbling as it comes. The Students’ Right to Their Own Language says, “We need to know whether ‘standard English’ is or is not in some sense a myth” (CCC, 1974, p. 3).

As a college student, I don’t get to treat Standard English as a myth because I have an assignment due tomorrow for which my instructions include, “WATCH OUT for comma abuse” and “Do NOT use contractions.” So for my Religious Studies professor, Standard English means no contractions and the taming of commas but for my English professor, perhaps not.

If professors are imposing their different versions of Standard English on every student, this is asking the student to change their language, and so, their identities: “Asking students to change their native discourse patterns to more closely match those of the school may be tantamount to insulting their home culture(s)” (White & Lowenthal, 2011, p. 18).

All of this culminates into a question about my role in academia, as a consultant. People like my Religious Studies professor are sending students to me: “If you have doubts or concerns about grammar,” he says in his syllabus, “I recommend you make use of the University Writing Center.”

I grew up with the “right” dialect to enable me to write in “Standard English” without really having to think about it. Like the Students’ Right to Their Own Language says, “Students who come from backgrounds where the prestigious variety of English is the normal medium of communication have built in advantages that enable them to succeed [in college]” (CCC, 1974, p. 4). This, in turn, allows me to talk to other students about Standard English.

But should I?

Is that my place?

June 4, 2016

My grandma hugs Brandon the moment she sees him. She takes a lot of pictures, as she always does, and comments on how handsome Brandon is.

My grandma hugs Brandon the moment she sees him. She takes a lot of pictures, as she always does, and comments on how handsome Brandon is.

We’re at a nice Italian restaurant for dinner. We eat delicious food and talk the whole time. My grandfather tells us how he met my grandma and then how he proposed.

“He didn’t propose at all!” Grandma exclaims. “He just started talking about a wedding and I realized, he was talking about marrying me!”

In the car on our way home, Brandon asks if I noticed the black woman who was staring at us during dinner. “You know about this right?” he says when we get in the car. “You know why she was staring at us?”

In the car on our way home, Brandon asks if I noticed the black woman who was staring at us during dinner. “You know about this right?” he says when we get in the car. “You know why she was staring at us?”

“Because you’re so handsome and she’s jealous I’m with you?”

“That’s cute but no. Say it. You know why.”

I don’t want to say it. I won’t.

He says it. “She was mad because I’m a black man and you’re a white woman.”

“Oh.”

“Do you know why she would be upset?”

“No,” I admit.

“Okay. Well let’s just look at the numbers. 40% of black men are in jail, did you know that?”

I don’t.

“So that leaves 60% that aren’t in jail. Then let’s narrow that down to men who are between twenty and thirty. And then men who don’t do drugs or drink. And then men who don’t already have kids.”

He pauses and then asks, “Who does that leave?”

“You.”

He laughs. “Me, and I know two other guys.”

July 7, 2016

I’m leaving for South America with my family in a few hours so Brandon comes over to say goodbye.

I’m leaving for South America with my family in a few hours so Brandon comes over to say goodbye.

We pray together for my trip and for my family. We thank God for bringing us together and ask Him to keep us until we can be together again.

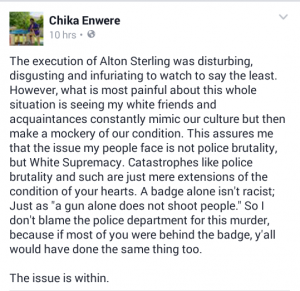

When we hug, I feel like crying because he’s alive and he’s here with me now. I want to tell him about Chika’s Facebook post, but I can’t. I don’t know how to say I’m hurting or why so I just keep saying, “I’m going to miss you so much” and “I love you.”

July 16, 2016

I’m in the Santiago airport in Chile, waiting for my flight to Easter Island and I’m reading “Listening to Ghosts” by Malea Powell for my independent study.

My dad is sitting on my right, and my little brother, Riley, is on my left, his head on my shoulder as he sleeps. The sun is coming up over the mountains, beautifully illuminating Chile – but I’m acting as a pillow and devouring Powell’s words, so I don’t get up to take pictures like everyone else.

I keep reading, instead, about language and power and oppression:

“I do this ‘alternative’ work to save my own life, to give sense and meaning to my existence as a human, that the simple possibility of what I have elsewhere called ‘mixed blood rhetoric’ is at the center of my having a story to tell at all, and that I am haunted by that having.” (Powell, 2002, p. 14)

Haunted by having a story to tell…

What is my story to tell?

What am I haunted by?

The night before we left for South America, five police officers were killed in Dallas, Texas; earlier that week, two black men were killed by cops. I was up until 2am praying and crying – one of those cops could have been my dad, a Brownsburg Police Officer for the last 20 years. One of those black men could have been my boyfriend, or anyone in his family – our church.

This sits heavily on my chest.

I am haunted by this.

Powel (2002) tells me what I’ve been doing since April: “A metaphor, then, for a kind of scholarly work that listens, and speaks, doubly. We gather up the strands from our multiple participations + we love them, name them as relatives and take them home = alternatives to academic discourses = listening to ghosts” (p. 19).

Those who haunt me make all that I’m studying real. I don’t have to name them because they already have names, they are “Dad” and “Brandon” and “Terry” and “Shantinique” who goes by “Shan” because, otherwise, she can’t get an interview.

They’re “Alton Sterling” and “Philando Castile” and “Trayvon Martin.”

“Senior Cpl. Lorne Ahrens,” “Officer Michael Krol,” “Sgt. Michael Smith,” “Officer Brent Thompson,” and “Officer Patricio Zamarripa.”

I hold the weight of them closer to my chest and walk with them further with every one of Powell’s words.

But how do I show everyone around me?

I’m listening. How do I get them to listen?

Powell (2002) ends her story, “. . . with an invitation, an invocation for all of us to listen, listen, listen to the whispers of those continental ghosts. To feel their shadows skim along the surface of our skin. To write our bodies into text and reinvent our writings in another voice, another language. To use history and family to remember the land upon which we play. To play these language games lovingly, tenderly, remembering that ‘all acts of kindness are lights in the war for justice’ (Harjo 1994, xv), all acts of scholarship are battles in a war of words, and of worlds” (p. 21).

I’m crying in the airport and Riley (who is awake now) and my dad are looking at me, concerned.

I tell them how language and culture are married and what it means when a language dies. I tell them how much my heart aches for the murdered men we flew away from a few weeks ago.

I’m asking them to carry the weight too.

I hope they’re listening.

August 28, 2016

It’s a Sunday after church service and Brandon’s mom pulls me aside to talk to me. We find an empty corner of the church building so we can speak in quiet.

She hesitates and I’m starting to get nervous.

Then she says something I don’t expect at all. “Sydney, I need to apologize to you.”

She hesitates again and then says, “I have to apologize because I had some racial prejudice in my heart that I didn’t even know about until my son started dating a Caucasian woman.”

First I’m confused.

Then I’m crushed.

“It’s one thing to have friends who are white. I have had white friends my whole life, some of my best friends,” she continues. “But when my son chooses to date a white woman, I think why wouldn’t he want to be with a woman like me?” She’s crying now. “But I know that’s not right and I see what he sees in you and I think you’re great and I’m sorry that I held that against you.”

I’m crying, too. I don’t know what to say.

After a minute, we’re both sniffling and she says, “Look Sydney, I really love you, so I just want you to know you can talk to me about anything, whenever you need.”

I tell her how grateful I am to be dating Brandon and to be so included in the family. I cry more, thinking of how blessed I am to know, and be a part of, a family that is so close, so open, and so loving.

We hug and leave for dinner.

Later, though, I think more about our conversation.

I feel bad for being white.

I’m thinking of that woman that was staring at us at dinner with my grandparents. I’m thinking of my older brother and “How black is he?” Of Brandon’s mom.

I’m thinking about the kids B and I talk about having some day: will they be called “not-actually-black”? And why does it matter?

I’m thinking of “Racism: Naming What Hurts” by bell hooks and of white supremacy. hooks (2013) says, “We can move beyond the us/them binaries that usually surface in most discussions of race and racism if we focus on the ways in which white supremacist thought is a foundational belief system in this nation” (p. 11). White supremacy is an undercurrent throughout all of the United States…but I didn’t even know it was real until April.

It is everywhere.

Is it in me?

September 22, 2016

I’m sitting at Starbucks, listening to music and reading through my notes from Students’ Right to Their Own Language even though I should be working on my Philosophy of Language paper that’s due on Tuesday.

I care about this more, though, and I’m feeling inspired from my walk and talk this morning with Marilee.

A black woman and her young daughter walk in the door in front of me; I glance up long enough to offer a small smile, before looking back at my notes.

After she’s ordered, she stands at the counter near my table and waits for her drink. She says something to me with a grin, and I take out my headphones so I can hear her repeat herself:

“You at it hard!”

Somehow I laugh and sigh in the same breath, “Yeahhhh.”

“You studying?” I nod my head and she asks, “What is it?”

I stand up, realizing it’s a good time to get a refill and answer, “Um, I’m majoring in Linguistics.”

“Ooooo,” she says like she’s excited to meet me. “How many languages you know?”

I laugh at her question; I’ve heard it many times. “Just English – I’m studying different dialects of English.” I want to tell her more but I’m nervous to, so I hold back.

“You know,” she offers, “I think about that a lot. Cause, see, I speak Ebonics and I notice now that she,” she motions to her daughter, “writes like us at school and I never even thought of that. Her spelling’s all wrong because of how we talk at home.”

I fight the urge to cringe. “Yeah, actually, I study what you call ‘Ebonics’ but some people call Black English or African American Vernacular English, as well as like Appalachian English, and Mexican or Chicano English – all of those forms of English are actually completely valid and good. There’s nothing wrong with speaking that way. So I’m studying how we need to work with people to use all of their forms of language how they want to.”

“Oh wow,” she says, still smiling. “You know, I’m gettin’ my Masters in business and I have to think about that all the time. ‘Cause I can write just fine, you know? But if I go into an interview talkin like I do, I won’t get the job! That’s corporate America.” She sighs. “Well we gotta go. You get back to it!” She says, with a smile that’s somehow more encouraging than the ones she gave me before.

So I do.

Later, Brandon and I are on our way to get pizza and he asks me how my independent study is going.

“It’s going well,” I say simply and after a moment I add, “I’ll probably write about you, if that’s okay.”

He laughs. “Why would you write about me?”

I don’t know where to start and I don’t know how to talk to Brandon about race. It’s like I’m afraid he’ll realize I’m actually white and run away.

“I mean, I met you at the Writing Center.”

“Yeah, I guess that makes sense.”

I let the rest of the truth wait for another day.

October 4, 2016

Brandon is dropping me off at my car after a walk at the park when I say, “I feel stuck in my independent study.” It’s time for me to say all the things I haven’t been saying.

“Hmm,” he says simply. “Did you schedule an appointment at the Writing Center?”

“Yeah, for Thursday.”

“That’s good,” he says. “It’ll help if you talk to someone about it. I’m sure you’ll figure it out.”

“Yeah… I feel like I have all these stories but I don’t know where to start.”

My heart is full of those stories.

Why haven’t I been telling him?

“Like… did I tell you about the woman I met at Starbucks?”

“Maybe. Remind me.”

I tell him about the black woman and her daughter who used “the wrong English,” as she put it.

He listens intently and, when I conclude my tale, with my inspirational words, “I’m studying how we need to work with people to use all of their forms of language how they want to” he pats my hands and says, “Good job, Babe. I’m proud of you.”

I smile shyly. But I haven’t said all I want to – all I need to, so I keep going.

“Thanks,” I offer. “It’s just…hard.”

“Why?”

I sigh. “Because I’m dealing with these really big topics and I just can’t figure out how to talk about them.”

Then I tell him everything – about his mom’s apology, and Students Right to Their Own Language, and how it all connects with the UWC. I talk about the murdered cops and black men that haunt me, and the question I ask myself almost daily, “What’s my place in studying this?”

Brandon listens, his arm around me, nodding his head.

I start crying twice.

He tells me about rap music and all that he’s learned from it. “People act like rap is so much less than other kinds of music but so many rappers are very intelligent but people say it’s a lesser form of music because they make judgements of the people who perform it.”

It’s almost like he’s quoting some of the scholars I’ve been reading for the past seven months. Laura Greenfield (2011) explained it like this:

Ebonics is stigmatized because it is spoken primarily by black people. . . Our attitudes towards language . . . are often steeped in our assumptions about the bodies of the speakers. We assume an essential connection – language as inherently tied to the body. In other words, language varieties – like people are subject to racialization. (p. 50)

We assume a connection between language and bodies and, as Ta-nehisi Coates (2015) wrote to his son, “In America it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage.”

I talk about the racist notion of “appropriate” places to use a home dialect (that isn’t “Standard English”), trying to quote Other People’s English: “Given the close relationship between language and identity, terms like inappropriate simply reinforce the view that expressions of African American identity are unwelcome in public settings that are dominated by Whites” (Hill, 1998, p. 51).

Or, like Geneva Smitherman (1974) says, in a way I’m not capable of saying, “Tellin kids they lingo is cool but it ain cool enough for where it really counts (i.e., in the economic world) is just like tellin them it ain cool at all. . . . See, we all time talkin bout preparing people for the mainstream but never talkin bout changing the course of that stream” (p. 731).

When I finally stop ranting Brandon says, “Well, I see why you’re stuck. You do have a lot of big topics and they’re all really important to talk about. I guess I didn’t realize this is what you were studying – now it makes a lot more sense why it’s taking so long for you to study it.”

“Yeah, I could research this my whole life.”

This research is my life.

I’m seeing it all like I’m looking at the stars at night. In the beginning, God created these.

They have always been but, now that I’m looking, I can see them – really see them.

The longer I look, the more I see.

Psalm 8:3-4 (English Standard Version) When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?

Who am I to be looking?

How do I get everyone else to look, too?

November 5, 2016

We’ve done it.

Our families are both together at my grandma’s house celebrating our birthdays.

Everyone is talking to each other. Everyone is laughing. Everyone is sharing.

Dinner is almost ready and my dad announces in the front room that we’re going outside to the gazebo to pray over the meal.

This is odd because my family doesn’t pray together – they don’t even talk about God.

I’m so excited. Brandon must have organized this. This is such a great idea.

We all mosey out to the gazebo and my grandma has us stand in front of it for a group picture. Terry exclaims, “Wait, we need some more white over here – to balance the color scale!” Everyone laughs.

I can’t stop smiling. I look around and all of my favorite people are together.

Terry prays and it’s beautiful, of course. He prays for the meal and for my family – my grandparents – and he prays for our time together. He thanks God for orchestrating our meetings.

I’m smiling the whole prayer. I can’t stop.

When we all say “amen,” everyone is staring at me and Brandon.

Brandon stands, pulling me up with him, and says, “Oh one more thing. Sydney, I love you.”

He’s down on one knee.

Englishes, Racism, and Me: An Epilogue

November, 2017

Reader, I married him.

I can’t believe that it’s only been five months since we were married. A year ago we started wedding planning and the reality of committing to spend the rest of our lives together started to sink in.

It was also a year ago, after Brandon proposed, that I finally knew how I would bring all my research together: I would combine my experiences and readings to exemplify how they support one another – and Brandon’s proposal would be the perfect conclusion.

In my research as I was questioning what the basis of standards in English were, I questioned standards in research methods as well. Shawn Wilson’s Research is Ceremony, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ letter to his son (an excerpt from Between the World and Me), and Malea Powell’s “Listening to Ghosts” showed me that I didn’t have to present anything linearly (although, in the end, I decided to). They showed me that I didn’t have to present my knowledge or research with a clear thesis statement or hypothesis at the beginning of my piece and a clean cut conclusion. They showed me that I have the freedom to re-present what I had learned and ask my readers to participate in my learning by walking them through a year of my life. Shawn Wilson (2008) writes that “Relationality requires that you know a lot more about me before you can begin to understand my work” (p. 12).So, my challenge last November was to sift through my litany of life experiences and research to find the most relevant of both so I could present them in a way that would allow my reader to see them as clearly as I did.

It was clear to me that my research would not be important if I could not show my readers why it mattered. People don’t seem to care about language biases unless you can explain who is harmed by them and how. And so I got to work piecing together all my strained and awkward talks with family members and friends. I translated all my emotional hours spent annotating texts about institutionalized racism and writing center pedagogy. I salvaged what I could from my independent study meetings with Marilee that I spent crying over questions I didn’t have the language to ask. I tried desperately to share this ever-growing weight that builds in my chest as I am constantly reminded that I will never have the privilege again to ignore any of this and that I have a lifetime to keep learning.

Now I realize, in a way I couldn’t a year ago, that, as I said at the conclusion of my piece, this research is my life. I don’t mean that to say that this is all I do or all that I am, but rather that all of it is intricately woven into me. Now, as I continue to do this research, I see how it connects to everything else in me and around me, including my work at the Writing Center.

Since I was engaged on November 5th last year, and concluded my original paper for my independent study, I’ve had a myriad more stories that I could use to expand this piece. These stories exemplify changes that go beyond me and reach into the lives of writers and other consultants. So now I ask that you do me the favor of reading one more story to try and give you a glimpse into those changes which were made possible because of an ever-growing and constant conversation that happens in our Center.

In the spring of 2016, I had a session with a young black man named Maurice. Maurice was graduating in May and it was his first time to the Writing Center; he clearly did not want to be there. He sat at a corner table with his laptop open and his arms crossed, waiting for me to join him.

When I did, he explained that he’d always been told he was a good writer but now he had a communications professor who told him he “needed to go to the Writing Center.”

Not even getting into the frustration of hearing that a professor was sending someone to us for “help,” I asked why the professor might say that. He shrugged and suggested that I look at what he had written for an online discussion thread to see if I could pinpoint his professor’s reasoning for sending him in.

He pulled it up on his laptop to read out loud to me (as reading out loud is strongly encouraged in our policy) and, as he read, I knew why his professor had not seen him as a strong writer.

Maurice combined African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and standardized dialects of English. His voice and opinion were strong, he made connections to the class notes and readings and he included personal experiences, but he did so with AAVE grammar patterns that many deem “broken.”

Of course, a year before, I wouldn’t have known any of that, but I knew it then and I tried desperately not to seethe openly.

When he got done reading, I said, “Well… how do you feel about it?”

He shrugged, exasperated. “I think it’s good,” he said.

“Yeah, I do too. Your ideas are clear and you write almost poetically.”

“I think that’s what she doesn’t like about it,” he said, still annoyed, but warming up a bit after my comment. “I think she just wants me to write it like everyone else but I don’t want to write it that way.”

I couldn’t help but laugh, “I actually do research on how professors want students to write in a ‘standard’ English, even though one doesn’t exist.”

His eyes got big and he leaned in a little closer, “Right?”

“Yeah, not everyone learns the same dialect of English growing up, so expecting everyone to use the same kind in school or in college is just unrealistic.”

“It’s kind of racist,” he asserted.

“It’s definitely racist.”

We both looked back at his paper and after a moment I asked, “So what do you wanna do?”

He closed his laptop. “I’m going to keep going like I am. I like how I write.”

“Good,” I said, trying not to beam, “You should.”

The conversation about institutionalized oppression and the Writing Center’s place in the institution is a cornerstone in our Writing Center. It is clear from the first class period in the Writing Center Theory and Practice class that we are not a fix-it shop for troubled writers, neither are we simply a place for writers to come to discuss their writing – but the Writing Center is a place where real change can take place.

When I gave the presentation that started it all in my linguistics class about the notion of standard English (see “March 20, 2016”), I thought I was getting my feet wet in a puddle of “Is this actually such a bad thing?” Instead, I fell into an ocean of institutionalized racism, white privilege and supremacy, education standards, tradition, family photos, and my future.

The presentation itself, however, was sparked by readings and conversations we had in the Writing Center class in the fall of 2015 and in the Center itself at bi-weekly staff meetings, often led by one or more of our committees which include: Writing Across the Curriculum and Outreach, Research and Assessment, Digital Resources and Online Consulting, and Language and Cultural Diversity.

We don’t talk about institutionalized oppression in every single staff meeting but it remains as an undercurrent throughout all of our work. For example, the Research and Assessment Committee led a staff meeting in which the committee members explained the consultant assessment form they developed and asked for feedback on how to improve it. Although this staff meeting was not about institutionalized oppression, the information gained from it (and the assessment sheet which was the topic of the meeting) can help us in identifying and uprooting ways that we perpetuate institutionalized forms of oppression in our Center. The point of the assessment sheet is that we can observe each other’s sessions and see what strategies we are implementing in the Center and if those align with our mission, goals, and values. Because student agency is key to a consultation there is an entire section on the sheet entitled, “encouraging writer autonomy and agency.” Our staff meeting, then, was still related to actively working against institutionalized oppression because we value our writers’ autonomy and agency and make it clear in the way we assess our sessions in the Center.

As a member of the Language and Cultural Diversity committee, I led a workshop with another committee member about Laura Greenfield’s “The Standard English Fairy Tale.” Every UWC staff member was asked to read the article before the staff meeting and at the meeting, discussed questions I developed from the reading in small groups which was followed by a large group discussion. This staff meeting was clearly more explicitly about the topic of institutionalized racism and oppression, but both meetings were important in different ways as we continue to grapple with the realities of being part of a system that so often oppresses people. Our staff meetings are opportunities for us to engage with Writing Center research and discuss how it applies to our Writing Center – especially if that research could possibly help us produce positive change in our Center, our University, and ourselves.

As we engage in this research and have these conversations, we must remember that we do this work to empower writers and give them opportunities to use their voices. The following is a response to an anonymous survey we ask every writer to complete after each session. I don’t know who this writer was, what dialect of English they grew up speaking, or their thoughts on language standards. In fact, I don’t remember the session at all. However, I know that in this session, I did my job and gave the writer the space to “be heard.”

Sydney gave me space to talk about my fear and confusions for my psychology research paper. Before the session, I felt lost. After the session, I felt heard and capable. I appreciate how I can freely talk about my entire writing process and catch what is going on and start to see my capability as a writer. . . The writing center is a great place for me to not only use my voice, but to be proud of my voice and my worth as a writer. (Emphasis added).

My session with Maurice and this survey response were isolated instances in which student agency was promoted and writers were encouraged to use their voices. They were given the space they needed to make decisions for themselves. However, these isolated instances are part of something much bigger – and that it what I have to constantly remind myself of when this work feels idealistic or tedious or anything in between.

The conversation about empowerment is not limited to people of color, but people of color are forced to live so much of their lives silenced by the dominant culture and by the institution. As a part of the institution we are able to acknowledge this truth and begin to uproot it. At the IUPUI University Writing Center, this has started to happen because it is such a part of the curriculum of the class and is therefore woven into the fabric of our culture as a writing center. To work in our writing center means being willing to contribute to this conversation and to take it very seriously – it is the foundation to everything we do.

For some, entering this conversation may happen through a provocative reading or engaging in a discussion about language rights and biases.

For me, entering the conversation was meeting an African American man whose talk about “equality versus equity” and “true diversity” irritated me – and the beautiful privilege and pleasure I now have to call him “Dad.”

References

Barrett, R. (2013). Be yourself somewhere else. In Young, W. A., Barrett, B., Young-Rivera, Y., & Lovejoy, K. B. (eds.), Other people’s english: Code-meshing, code-switching, and african american literacy (33-52). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Brooks-Gillies, M. (2016, February 26). Wonderful st. hermione’s day celebration! Thank you all for your wonderful spirit and generosity! [Facebook post]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/groups/250712609674/permalink/10153915461414675/

CCC. (1974). Students’ right to their own language. College Composition and Communication. 25, 1-23.

Coates, T. (2015, July 4). Letter to my son. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/07/tanehisi-coates-between-the-world-and-me/397619/

Enwere, C. (2016, July 7). The execution of Alton Sterling. [Facebook post]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/chika333/posts/1033342316703168.

Fleck, S. (2016, April 9). In a relationship. [Facebook post]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/637249526/posts/10153716332214527/.

Fleck, S. (2016, November 5). In case you missed it. [Facebook post]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/sydney.fleck/posts/10154219930549527.

Friere, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Greenfield, L. (2011). The “standard english” fairy tale: A rhetorical analysis of racist pedagogies and commonplace assumptions about language diversity. In L. Greenfield & K. Rowan (eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 33-60). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Harjo, J. (1994). The woman who fell from the sky. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Hill, J. H. (1998). Language, race, and white public space. American Anthropological Association, 100(3), 680-689.

hooks, b. (2013). Racism: Naming what hurts. In, Writing beyond race: Living theory and practice (9-25) New York, NY: Routledge.

North, S. (Sept., 1984). The Idea of a writing center. College English. 46(5), 433-46. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/377047

Powell, M. (2002). Listening to ghosts: an alternative (non)argument. In P. Bizzell, C. Schroeder, & H. Fox (eds.), Alt dist: alternative discourses and the academy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Smitherman, G. (1974). Response to Hunt, Meyers, et al. College English, 35(6), 729-732. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/journals/ce/issues/v35-6

White, J.W., & Lowenthal, P.R. (2011). Minority college students and tacit ‘codes of power.’ Review of Higher Education, 34(2), 283-318. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2010.0028

Wilson, Shawn (2008). Getting started. In, Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods (12-21). Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.