Meghan Woolley, Idaho State University

Jacqueline Allain, Bard High School Early College

Abstract

Building on a growing body of work that reflects on writing center history and archives, this article explores the process of constructing writing center archives and reflects on their utility. In particular, it illustrates the usefulness of collecting oral histories from writing center consultants. It analyzes sample interviews from previous writing center consultants of two different university writing centers and considers how they might be useful for strategic planning and creating institutional memory. The results show the importance of centering staff experiences within writing center histories and institutional archives. Overall, this article contributes to theorizing what a writing center archive can look like and provides practical insight into how writing center administrators might collect and use oral histories, as well as other archival materials.

Keywords: writing centers, archives, oral histories, institutional memory

Introduction

Building on a small but growing body of scholarship on writing center history and writing center archives (Carino, 1995; Bouquet, 1999; Smitherman, 2003; Nall, 2014; Austin, 2020), this article offers a nascent attempt at theorizing what a writing center archive might look like and the analytical and planning uses to which such an archive could be put. Drawing on both our professional training as historians and our engagement with writing center praxis through our work as writing center consultants, we explore the following questions: what would a writing center archive consist of, and what would be the utility of such an archive? Our contention is that in the face of aggressive budget cuts and increased precarity, the safeguarding of writing center institutional memory is crucial for strategic planning purposes.

This article is anchored in eleven open-ended oral interviews conducted via Zoom with former writing consultants at the On-Campus Writing Lab (OWL) at Purdue University and the Writing Studio (WS), part of the Thompson Writing Program (TWP) at Duke University [1]. In part because many institutional records provide an administrative perspective, these oral histories focus on writing consultants in order to highlight staff experiences. Although these interviews are too few, arguably, to constitute an archive in themselves, they offer a proof-of-concept hermeneutic through which we explore the purposes toward which a writing center archive might be put. Many writing centers may benefit from building their own collection of oral histories, which can work alongside other historical materials, such as staff documentation, reflections, and interviews. Consultants’ histories, as the following analysis will show, can be particularly useful for reflecting on staff training and support. These oral histories are complemented by an additional three interviews conducted with writing center administrators who have worked with oral histories at their own institutions, providing reflections on how these materials can be resources for building institutional memory, organizing community partnerships, and supporting staff professional development. It is our hope that the following analysis of oral histories demonstrates possibilities for how writing centers can actively use these materials. When managed proactively and made accessible, writing center archives have the potential to support staff training, pedagogy, and programming.

Archives and Institutional Memory

Writing center archives are an underutilized resource within the broader field of the history of higher education. The utility of university archives to anyone interested in the history of higher education is overt. Many a fine study on college student activism, student social organizations, institutional decision-making, and employee labor organizing has been conducted on the basis of material housed in university archives. Beyond the history of higher education, these studies offer valuable insight into the history of the state, social movements, gender formations, labor, and intellectual and pedagogical trends and shifts.

This article focuses on yet another important use to which writing center archives, in particular, could be put: institutional planning. Although attempts at constructing writing center archives have been infrequent, they are not non-existent. Those professionals and organizations at the helm of such attempts have been motivated, for the most part, by a desire to preserve institutional memory for planning purposes. As early as 2003, Carey Smitherman Clarke was urging writing center professionals to begin building institutional archives, especially through the collection of oral histories. As she argued, “these archives can be an invaluable resource for writing center administrators. Historical information may help with budget negotiations, grants, and the further professionalization of writing center administrators at a particular institution” (p. 3). Moreover, the collection of oral histories “is urgent for the historical understanding of the writing center community by providing documentation of the perspectives of early and influential writing center administrators as well as the politics of important events in the writing center movement” (p. 3). Oral histories are an important component of The Writing Centers Research Project (WCRP), currently housed at the University of Central Arkansas, which is a leading effort to form an inter-institutional repository of “scholarly materials related to writing center studies” (“Writing Centers Research”). In addition to books, academic articles, and tutor training materials, the WCRP collects oral interviews with “historically significant writing center professionals,” such as writing center founders.

Other writing center oral history collections include those at the University of Louisville, begun in 2015, and at Michigan State University (MSU), initiated in 2019. MSU’s project includes interviews of past consultants reflecting on their experience working at the writer center, including topics such as training, organizational culture, and different programming initiatives, conducted by current consultants. According to the project’s website, “critically examining our storytelling practices and how our organization’s stories are situated within institutional ecologies will inform our strategic planning process moving forward” (“The Writing Center”). This project illustrates how both archival materials themselves and reflecting on archival practices can inform institutional planning, uses that are further explored below in the discussion section.

More recently, rhetoric and composition scholars Stacy Nall (2014) and Roger Austin (2020) have contended, similarly, that individual writing centers must build their own archives for strategic planning purposes. Austin (2020) emphasizes the importance of pairing oral histories with the systematic collection of physical documents. Nall (2014), in particular, advocates for incorporating more perspectives from staff members, student writers, local community partners, and on-campus collaborators into writing center archives. We second Nall’s view that the collection of oral histories from all levels of writing center employees, not just administrators, is vital to the project of institutional memory-building. This project takes a small step towards filling this gap, building on work such as that by MSU. By collecting oral histories from writing consultants, we prioritize staff experiences, told in their own voices. In our analysis of these histories, we highlight the different themes that consultant oral histories might illuminate, and how they might productively inform our writing center practices.

Methods

To recruit interviewees, we contacted former employees at the Purdue OWL and Duke WS. In some cases, we had personal relationships with our interviewees. In other cases, we found them through simple Google and LinkedIn searches, or through snowball sampling. Following the best practices laid out by the Oral History Association, we provided interviewees with the objectives of our project in advance and our expectations– “what [we] want[ed] to get out of the process, what topics [were] meaningful to [us].” We also provided interviewees with questions in advance. We conducted all of our interviews via Zoom and recorded them.

We selected the Purdue OWL and Duke WS because of our former professional affiliations with these institutions, enabling richer insight into their institutional histories and practices, as well as the ability to use personal connections as a starting point for recruiting participants. Both writing centers are located in R1 universities with large multilingual student bodies. Both universities also have relatively large writing centers with both professional and student staff. The two universities also differ in meaningful ways. Purdue University is a public university with an acceptance rate of about 50%. As of Fall 2024, approximately 46% of its student body comes from in-state, and the university serves local rural student populations (“Student Enrollment”). Duke University is a private university with an acceptance rate of about 5% (Lu & Penner, 2024). As of 2024, approximately 84% of its student body comes from out of state (Eng, 2024). Including both universities within this study enables us to analyze trends in writing center experiences across similar types of institutions, while also exploring how oral histories can reveal experiences and needs that are unique to individual writing centers and connect to distinct campus cultures.

Purdue University On-Campus Writing Lab (OWL)

Purdue University’s Writing Lab is uncommonly rich in archival materials, benefiting from past and present directors with a commitment to maintaining an institutional history. Since its establishment in 1994, Purdue’s Online Writing Lab, which receives hundreds of millions of annual pageviews, has cultivated attention to the Writing Lab’s history. This prominent public profile informs the OWL’s commitment to record keeping and also its awareness of a public audience. The Purdue OWL therefore faces a heightened challenge that many writing centers may share, between archives as internal recordkeeping and archives as public-facing narratives.

In its archives, the Writing Lab has digitized annual reports dating to 1975, detailed data on Lab usage by the Purdue community since 2015, and even a couple of outdated hard drives that used to house the entire OWL website. Since 2021, the Purdue University Library has also preserved a collection of physical archival material including administrative files, pamphlets, handouts, and training guides. In addition, the Lab maintains an online collection of research, publications, and research from its staff and students. These materials present opportunities for academic work on writing center activities, writing center studies more broadly, and the more practical development of programming and partnerships. Beyond these centrally organized materials, individual staff members have additional information such as survey data, workshop repositories, and video interviews with past clients and consultants. For writing centers with similar materials, efforts to place files from different staff members within a shared, accessible system, to the extent that privacy concerns and IRB procedures allow, can create additional resources for research and institutional planning.

The former Purdue OWL employees from whom we collected oral histories were as follows:

-

Stacy D., who worked as a Graduate Teaching Assistant (GTA) from 2012 to 2016 while completing a doctorate in Rhetoric and Composition. Stacy also provided content development work for the OWL website.

-

Carrie K., who worked at the OWL from 2014 to 2018 while she was a PhD student in the Theory and Cultural Studies Program in the Department of History. She first worked solely as a GTA, and then as both a GTA and Introductory Composition liaison. As liaison—a position that no longer exists—Carrie worked ten hours a week to incorporate the writing center into first year composition and other classes.

-

Colleen A., who worked as a Business Writing Consultant (BWC) from 2017 to 2019 as an undergraduate Computer and Information major and English minor. BWCs offered specialized tutoring in business-related and job documents, such as resumes, cover letters, memos, and reports.

-

Nathan M., who worked as an Undergraduate Teaching Assistant (UTA), copy editor for the OWL website, and Writing Fellow from 2016 to 2018 while completing a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology and Philosophy. Between the fall of 2022 and the winter of 2023, Nathan also worked as a Professional Writing Specialist (PWS), a full-time staff position, at the OWL.

-

Jacqueline B., who worked as an UTA from 2010-2012 while studying Linguistics and a GTA from 2021-2022. Jacqueline has also worked as a PWS since 2022.

Assignment Types

The oral histories show a trend in assignment types of increasing numbers of graduate student writing and professional documents, such as resumes and graduate school applications. From her days as a UTA in 2010-2012, Jacqueline remembers working on mostly undergraduate student papers, including work on “everything,” from a range of disciplines. From 2012 on, the consultants recall a wider range of types of writing and an increasing amount of graduate student work. Jacqueline identified this as one of the biggest changes between 2010 and 2022, reflecting that she spends the majority of her more recent sessions working with graduate students. Both Carrie and Nathan also highlighted working with graduate student writing such as dissertations, theses, conference papers, and book chapters. Between 2016 and 2018, Carrie found that “the genre that I saw the most was dissertations,” particularly from students in STEM. These sessions were often with repeat clients, many of whom were multilingual writers, who “would feel safe” booking weekly sessions to keep working on their dissertations. Nathan reflected that during both of his roles as UTA (2016-18) and PWS (2022-23), he worked with many graduate students working on theses and dissertations as well as conference proposals and manuscripts for publications, particularly in the 2020s.

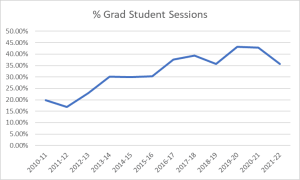

These consultant observations reinforce a pattern visible within the OWL’s usage statistics. Between 2010 and 2022, the percentage of sessions held with graduate students climbed from 19.8% to a peak of 43.2%, as seen in Figure 1. Consultant oral histories add an element of personal narrative to this data, highlighting the day-to-day impact shifts in usage can have on the experience of consulting.

Figure 1

Percentage of OWL Sessions Held with Graduate Students, 2010-2022

Another significant increase was in the amount of graduate school application materials. Between 2012 and 2016, Stacy worked on many personal statements for graduate school applications, recalling that “some weeks it felt over half, if not more, of my sessions were personal statements.” Speaking about personal statements, Carrie also noted that “I saw a lot of those, always.” Nathan also mentioned that in addition to academic papers, he worked on “a lot of resumes, cover letters, [and] graduate school application essays like personal statements, statements of purpose.” This type of reflection from writing consultants could be useful to administrators to identify priorities for future staff training.

In addition to the types of writing, these interviews showed how working with different genres impacted the experience of consulting. Some consultants reflected on working with technical writing in different fields as a difficult component of writing center work. Stacy noted that working through technical language in genres like advanced engineering papers was a challenge, noting that specialized training in topics such as preferred sentence structure in STEM fields could have been a “good area for further professional development.” On the other hand, consultants noted that the variety of writing they worked with could be rewarding. Jacqueline told us that working on different kinds of things was her “favorite part of the job,” describing how she learned about topics ranging from bridge inspection in Indiana to Chinese settlers in the Mexican borderlands. Working with writers from across the disciplines, therefore, is simultaneously a challenging and enriching part of being a writing center consultant.

Professional Development and Specialized Training

Oral histories can be an excellent source to show what elements of training writing center staff found most useful. For undergraduate students at the OWL, becoming a consultant requires taking a training course. Colleen recalled, “you had to take a one-credit hour course with the faculty leaders at the time,” which involved “reading multiple different writing lab books, learning how to properly mentor somebody and coach somebody in their writing, and then also in general learning what a good document looks like and being able to identity [that].”

Graduate student consultants also participated in extensive training. When Carrie began working as a tutor at the OWL, she took part in a once-weekly hour-long practicum taught by the interim director of the lab. Carrie described this training as a “pretty traditional writing center practicum” that consisted of reading writing center scholarship, reading the Bedford Guide, and going over hypothetical tutoring scenarios. She also recalls there being “a lot of training involved in our staff meetings,” which occurred every other Tuesday morning. Representatives from different departments sometimes attended these meetings to alert tutors to upcoming assignments and explain their expectations for the assignments, which Carrie recalls finding helpful in preparing to tutor students from a wide range of departments. During her first two years as a consultant, Carrie also took part in monthly brown-bag workshops on various themes. As with the staff meetings, these workshops “had the effect of preparing you as a tutor to see different types of assignments.” For most of the time she worked at the OWL, Carrie remembers that every graduate-level tutor was required to facilitate two workshops a semester on various writing topics. While there were “a couple vocal opponents to that requirement” on the grounds that it was logistically inconvenient, Carrie found the requirement “tremendously useful for my career going forward.” While these workshops were mainly attended by students, Carrie was eager to encourage university staff to attend.

Multilingual education was a particularly important theme within consultant training. Carrie recalled that every spring, tutors took part in an “intense” English as a second language (ESL) training, which she described as “incredibly helpful.” Colleen also pursued training in ESL, as well as required business writing training. She remembers training in cross-cultural competency and pedagogy as being a significant component of the training she received. Nathan, like Colleen, spoke of taking a training course in writing center studies. “There was a lot of reading involved, we did shadowing in the lab, and there was an end of semester project,” he recalls. He also remembers undergoing significant training “centered on multilingual and ESL writers.” This training occurred asynchronously, through Blackboard.

This type of specialized training corresponds to the growing enrollment of international students beginning in the 2010s. Between 2010 and 2019, the enrollment of international students at US universities increased from approximately 723,000 (3.5%) to over 1 million (5.5%) (“Enrollment Trends”). Many writing centers subsequently saw an increase in the number of multilingual students visiting them (Best, 2018; Rentscher & Kennell, 2018). The OWL met this need in part by hiring an associate director with a specialty in multilingual education in 2012. Consultants’ oral histories show the centrality of this specialized training within their memories; dedicating staff and resources to training in working with multilingual writers had a noticeable impact.

Appointment Structure

Oral histories also provide useful insight into what makes appointments successful from a consultant standpoint and how changes in technology have worked in practice. Many of our interviewees from Purdue reflected on the differences between online and in-person tutoring. According to Carrie, when she worked at the OWL, most appointments were in-person, but synchronous and asynchronous online sessions were also available. Though specialized training was provided for asynchronous tutoring, Carrie reported feeling that asynchronous consulting can “veer so easily into editing” and preferred synchronous modalities, including online synchronous. The only software available for online synchronous tutoring was a “chat function” without video conferencing. Even without a video conferencing feature, this system “worked pretty well,” because writers were able to chat with tutors and edit their writing in real time. Carrie was not alone in her ambivalence about asynchronous tutoring. At first, Colleen found the asynchronous sessions “stressful” because students used them as a copy-editing service. “I remember the asynchronous tutoring sessions being really really stressful because it was basically like you were being handed off a document to copy edit.” She noted that the director and the rest of the staff were very responsive in writing new rules for the expectations for writers sending in asynchronous documents, and that they were proactive in responding to consultant input. Today, the OWL dedicates significant training to asynchronous tutoring.

Purdue OWL interviewees indicated that tutoring slots ranged in length from 30 minutes to an hour. Some reflected on the merits of different session lengths, with both Jacqueline and Carrie indicating that they felt the 30-minute slots were too brief. Nathan noted that a 30-minute session did not allow enough time for goal setting. Colleen, on the other hand, who worked primarily on business on job documents, found that clients who booked 30-minute sessions were “arguably more driven” and “prepared” than those in hour-long sessions. She found that more ESL students booked hour-long sessions, which provided more time to work through language barriers.

When discussing how they structured appointments, multiple OWL interviewees recalled taking time at the beginning of the session to set agendas and leaving time at the end of the appointment to wrap up the session. This “wrap up” time became especially important once the OWL began including session notes sent to writers as a standard part of each appointment. Depending on the session and consultant, these notes can be filled out collaboratively with the client or independently by the consultant. Prior to 2022, the OWL suggested that consultants leave five to ten minutes at the end of each session for composing these notes. For some consultants, this felt insufficient. “I definitely felt the pressure,” Jacqueline noted, “and many of us would get behind on our session notes in that format.” Beginning in the summer of 2022, the OWL adjusted the format to set hour-long appointments as the default, with forty-five to fifty minutes spent tutoring. The extra ten to fifteen minutes are dedicated to session notes and a small break between sessions. Jacqueline emphasized how helpful this change has been, stating that, “I do not get behind on my session notes anymore.” In practical terms, having time to use the restroom or get water also makes a shift of consulting easier. This change in session structure is a positive example of responding to staff needs. Administrators often receive this information from real-time staff feedback, but oral interviews can provide an additional opportunity to explore this kind of consultant experience that can inform administrative decisions.

Staff Dynamics and Community Building

Oral histories provide insight into behind-the-scenes aspects of writing center work that are less visible in published sources. Multiple participants brought up the importance of community and collaboration among staff. Colleen noted that in her time at the OWL, a helpful practice was participating in organized social sessions, where she was able to get to know other people at the lab. Nathan, whose time at the OWL overlapped with Colleen’s, also shared that the undergraduate consultants spent a lot of time together outside of the writing center and were able to have informal conversations in the lab’s back room. These connections formed the foundation of collaborations during sessions. According to Colleen, when faced with a document she felt less comfortable with, she would ask other undergraduate consultants, graduate students, or senior staff for advice, or even trade documents based on expertise. Colleen and Nathan’s interviews showed that consultants felt comfortable turning to each other as resources and regularly collaborated during sessions.

This kind of organic dynamic can shift subtly over time. In 2022, the OWL moved to a new building on campus, with consultations held in a shared student work space. The new space has brought some advantages. Jacqueline commented, “I think that we’ve gotten more visible. It feels less like our space, which can feel very intimidating to students.” The OWL usage statistics support this increase in visibility and accessibility; on-site traffic increased from 1,192 face-to-face sessions in the 2021-22 academic year to 2,770 in 2023-23. Unlike the previous location, however, the new space does not include a “back room” that consultants regularly congregate in. Nathan observed, “we don’t have as much opportunity to kind of informally interact with other tutors or other staff members…that’s affected the interpersonal dynamics.” As a result, the new lab culture feels “a little more rigid.” Jacqueline, who has also been at the lab during the transition to a new space, echoed this sentiment. “The spontaneous connections we used to make” including “asking a quick question about e-tutoring or just chatting about what we’re doing for today…are not occurring.” She reflected that this could be especially challenging for new undergraduate consultants and hoped that after transitioning, the lab would cultivate more informal connections between staff. Nathan and Jacqueline’s experiences are also reflected in survey data collected by Jacqueline in a study on space, in which a number of additional consultants reported a drop in spontaneous interactions with peer colleagues and with administrators (Borchert, 2024).

These changes associated with a move across campus affirm the emphasis in a wave of recent work on the importance of space for writing centers (Azima, 2022; Zammarelli & Beebe, 2019; Purdy & DeVoss, 2017; McKinney, 2013). Although writing centers may have limited control over their space on campus, they can use oral histories like those above to check in on staff responses to their environment. Especially during moments of transition, writing center administrators can draw on this type of insight to preserve a collaborative culture.

Thompson Writing Program Writing Studio, Duke University

Established in 2000, the TWP offers a selection of programming, including a sequence of mandatory writing seminars for Duke freshman, a Writing in the Disciplines certificate for graduate students, and the services of the Writing Studio (WS). Over the years, WS staff have produced an abundance of handouts that provide guidance on, among other things, genre, process, and style. Some of these handouts exist as hard-copies for distribution at Writing Studio locations, but most can be found on the WS website as PDFs (“Writing Resources” ).

The former TWP WS employees from whom we collected oral histories were as follows:

-

David S., who worked at the WS in 2000. At the time of his employment at the WS, he held a BS and MS, both in engineering, and an MDiv. He was a PhD student in Religious Studies.

-

Felicity T., who worked as a WS tutor during the 2006-07 academic year while a PhD student in the Department of History, at which point she held a BA and MA in history.

-

Bradley B., who worked at the WS from 2009 to 2013 as a PhD candidate at a separate institution, at which point he held a BA and an MDiv.

-

Zackary V., who worked at the WS from 2010 to 2014 while a PhD candidate in English at a neighboring university, at which point he held a BA and MA in English.

-

Yair R., who worked at the WS from 2018 to 2020 while a PhD candidate in the Program in Literature. He held a BA in political science.

-

Andrew W., who worked at the WS from 2020 to 2022 as an embedded writing consultant within an Engineering 101 course and as an undergraduate writing consultant. He was completing an interdepartmental major in history and art history with a second major in public policy.

Assignment Types and Writing Genres

With the exception of Brad, who recalls working with writers on “everything” in terms of genres and assignments, the oral histories collected from former WS employees who worked at the WS prior to 2018 convey significantly less variety in the types of assignments and genres of writing that writers came to work on than did Purdue OWL employees. David recalled working with writers primarily on “standard research papers.” Felicity, according to her recollection, saw mostly humanities and social science essays, and very few STEM papers. Zackary mentioned working with writers on papers from the university’s freshman writing seminar sequence. Yair and Andrew, who worked at the WS most recently, indicated working with writers on the widest range of genres, from the widest range of disciplines. Andrew recalled working on “a little bit of everything,” including freshman writing assignments, policy memos, resumes, cover letters, and poetry. He worked with writers from different fields, including STEM fields such as engineering, and both undergraduate and graduate students.

These interviews, although representing a limited sample, show an increase in the diversity of assignments and writer fields from 2000 to 2022. This speaks to the importance of writing centers advertising their services widely across the disciplines. In particular, it suggests that embedding writing tutors in STEM classes, such as Andrew’s role within Engineering 101, can work effectively to bring more STEM students into writing centers. The fact that consultants at both writing centers reported an increase in disciplinary diversity and usage by graduate students shows a broader trend of more kinds of student writers viewing university writing centers as a valuable tool.

Professional Development and Specialized Training

All six WS interviewees recalled receiving some degree of training and professional development. Andrew, reflecting on the WS’s most recent training practices, recounted participating in a weekend of professional development at the beginning of each year, followed up by meetings a few times a semester. Brad relayed that he took part in a training at the beginning of the year in which more experienced tutors shared their experiences and participants took part in sample sessions with other tutors, among other activities, which he found helpful. David recalled taking part in a multi-day training “retreat” that required “a lot” of reading. Part of his professional development involved creating handouts. He remembers working on a handout titled “How to Make a Claim and Support it with Evidence.” According to Felicity, the onboarding training was “rigorous,” lasting one or two days, supplemented by shadowing appointments. She also recalled being required to hold workshops for students and update handouts, the latter of which, like David, she counts as a form of professional development. In contrast to David and Felicity, Zackary recalled receiving “Some training, not a lot.” An explanation for this disjuncture might lie in the fact that what constitutes “rigorous” is ambiguous.

Some participants noted gaps in their training. Zackary did not recall receiving training in anti-racist pedagogy, an “ever-present issue that I think we should have had more training on.” Similarly, Felicity expressed the wish that she had received training in working with ELL students. While Yair found the DEI-centered training useful, he felt that many of the professional development sessions were “abstract.” Instead, he preferred the ones that offered more practicable tips, especially in terms of working with culturally and linguistically diverse students. Andrew reflected on a particular challenge presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the fall of 2020, the WS transitioned from in-person sessions to holding online video sessions over WC Online. Consultants did participate in some training on remote tutoring practices, such as respecting student privacy when video conferencing from personal spaces. However, he found ongoing challenges in adapting to the new platform and encountering different expectations from writers. His account suggests that proactive, ongoing training and staff reflection would be useful in circumstances that require consultants to learn new technology or adjust their tutoring strategies. Overall, these consultants’ interviews reveal important priorities when it comes to tutor training: anti-racist pedagogy, working with multilingual writers, and adapting to change.

Many of the WS interviewees expressed that working at the WS enhanced their pedagogical facility and their own writing. Andrew described how the training course to become a writing consultant, alongside taking a first-year writing course, “made me fall in love with writing all over again.” As someone who entered college not feeling “super confident about writing,” he was able to build confidence in both his own writing and his ability to support other writers. For David, training as a writing center consultant has also informed his longer-term career accomplishments. David is currently a professor at a theological seminary in the midwest, where he also co-directs a prison education program. For him, working at the WS was “formative for me to really get me to think about both writing myself as well as how to teach other people how to write.” When he arrived at his current institution, he helped found a writing center based roughly on Duke’s WS, and the prison education initiative he directs contains a peer-tutoring program. Although he is no longer involved in his school’s writing center or in the training of peer tutors through the prison education program, working at the WS familiarized him with the workings of a writing center “from the inside-out,” helping him become a “good organizer of these services.” Zackary, who is now an associate professor of English at UNC Chapel Hill, has also built on what he learned at the WS in his later work. He told us that when he used to teach writing, he frequently used the studio’s handouts, many of which he had helped create.

Interviewees also highlighted the positive impact of working with students. Felicity recounted working with an undergraduate writer who reported that when she found herself “stuck,” she did her writing in the bathroom, because growing up, the bathroom was the room in her family home where she could find a quiet space to write. “I learned something there from that student,” Felicity reported. “I learned a lot about myself and the kinds of assumptions I had come to have about Duke students.” By this, Felicity was referring to the stereotype of Duke University students as being predominantly from elite backgrounds. She also learned more about how writers’ habits and preferences vary. Yair, who has left the world of higher education, expressed that the experience he gained in mentorship improved his career readiness by helping him cultivate a transferable skill set. In these ways, the WS interviewees conveyed that working at Writing Studio better prepared them to reflect on their own writing, to meet the needs of diverse students, to oversee the administration of academic programing, and to teach writing.

Staff Dynamics and Community Building

The Duke oral histories demonstrated the importance of community building and a collaborative environment to their experience as consultants. In his interview, Brad indicated that he found the WS’s “team” atmosphere helpful. Scheduling multiple tutors per shift allowed tutors to collaborate and troubleshoot while working. Andrew’s testimony, similarly, highlighted that he particularly valued the collaborative culture of the studio, which included opportunities for student consultants to develop their own programming through committees. When describing his experience, he emphasized that how the staff, including both undergraduate and graduate student consultants, viewed each other was not hierarchical. Instead, they viewed each other as co-workers and peers. “Over time,” he recounted becoming “pretty close with a lot of the other writing consultants.” This also aligned with the pedagogical mission of WS to be a welcoming space, where consultants did not impose what to do on writers. In this way, the culture and writing instruction at Duke’s WS were mutually reinforcing.

Andrew also described a unique element of professional development and programming at the WS: committees led by student members of the staff. Each committee was dedicated to a different topic, such as racial equity or environmentalism. As a member of the environmental committee, Andrew spearheaded a program for student re-use, creating “the only permanent drop-off spot for reusable items on campus at the time.” At a table in the WS, members of the campus community could drop off items such as notebooks or clothing, or take what they needed. He felt this fit with the way the WS interacted with student writers, encouraging them to “generate ideas, reuse ideas.” Andrew’s interview demonstrates that by supporting staff-led initiatives, the WS cultivated creative programming that could advance staff priorities and help the campus community. This evinces an approach other writing centers may wish to try in order to expand their connections with the broader campus and to fill staff-identified gaps in training and programming.

Discussion

One of the limitations of our interview sample is that the majority of our interviewees identify as white. Our interviews did not include direct questions about how gender, sexuality, or other identity categories may have affected their experiences as writing center tutors, and none of our interviewees broached the topic. Previous studies, however, have shown the importance of identity for both tutoring and staff dynamics (Denny, 2010; Lockett, 2019; Natarajan & Morley, 2020; Haltiwanger-Morrison, 2021; Sicari et al., 2021). Understanding how identity and embodiment shape the experiences of writing center staff is an area that future writing center oral histories can contribute to. Writing center administrators may also find that collecting oral histories that reflect on identity may help them to support diverse staffs.

A few general conclusions can be drawn from these interviews. For one thing, the majority of our interviewees from both institutions expressed to us that the training and professional development they received while working at their writing centers was useful, and many provided specific examples of what in particular they found instructive. In some cases, interviewees expressed a desire to have received more intensive training in multicultural tutoring and intercultural pedagogy. Some of our OWL interviewees emphasized the importance of community building among writing center staff. Our WS interviewees conveyed that they consulted with writers on a more limited range of genres and assignments than did our OWL interviewees, indicating a potential need for more aggressive outreach across the disciplines. These tacit observations provide but a snapshot of the kind of analytical purposes to which a more systematic, broader collection of oral histories could be put. Writing center administrators and staff could use such interviews to plan for training and professional development, appointment structure, advertising and outreach, and staff community-building.

Building up writing center archives does not need to be a labor- or time-intensive endeavor. The oral histories that informed this article were twenty to thirty minutes long and simple to record using a video conferencing tool. One concrete strategy writing centers could employ would be to invite their consultants to record annual reflections or exit interviews, either in interview format or by individually recording answers to a set of pre-written questions. Another model, employed at the University of Louisville Writing Center, is likely to be easily replicable by other small- to medium-sized writing centers: at the start of every spring semester, when traffic into the center is low, student consultants complete “January Projects.” One of these projects was an oral history project. Students completed training in oral history methods and conducting virtual interviews, then conducted oral histories with former directors and consultants. Bronwyn Williams, former director of the University of Louisville Writing Center, noted that student consultants got an enormous amount out of conducting oral history interviews, shaping “how they thought about their work going forward” and connecting them to a larger, ongoing writing center community. This kind of model creates minimal work for administrators and also supports student consultants, who can develop a skill set in oral history while also building connections to their own writing centers.

Writing centers could also encourage their student consultants to use their centers’ own collection of oral histories for class assignments, conference papers, small research projects, or master’s theses. This might be an especially appealing option for writing centers that train new consultants through a semester-long course and ask those students to complete individual projects. Oral histories could furnish new material for student research into writing center studies while also helping to familiarize incoming consultants with the center’s work. By involving student consultants as the subjects, interviewers, and researchers of institutional oral histories, writing centers can enhance institutional insight and staff professional development at once.

As the overviews of archival materials at our two universities have demonstrated, most writing centers already have material that could be considered an archive: annual reports, student papers, staff surveys, exit interviews, program reflections, past workshop materials, desk journals, marketing materials, and so on. Many of these materials are digital, which can make materials accessible but also poses new challenges for administrators, historians, and archivists (Carbajal & Caswell, 2021). These resources can regularly be of service to writing center administrators and staff. A key challenge, in most cases, is making these materials accessible, both in terms of availability and organization. In the process of researching this article, the authors learned about materials at their own institutions they had previously been unfamiliar with. Many writing center staff surely have similar gaps in their knowledge and miss the opportunity to learn from their predecessors. Recognizing the value of these materials as an archive and storing them within a centralized system can go a long way in preserving institutionalized knowledge. Some writing centers may find it useful to create separate collections for internal and public-facing materials, which could encourage staff to save more material.

Moreover, when possible, we encourage writing center administrators to liaise with librarians and archivists, who often possess specialized knowledge in the logistics of archive-building and administration, at their institutions. Many university and college libraries already house university archives, to which writing center archival materials could make useful additions. In the absence of such archives, it is still worth collaborating with library personnel. One area in which librarians and archivists may offer insight is organization. Writing center materials are often stored across individual administrators’ devices or grouped together in unwieldy folders. Tim Johnson at the University of Louisville, for example, noted the challenge of navigating a Google Drive folder holding twelve years’ worth of material. University librarians and archivists could be essential collaborators in developing systems–or applying pre-existing university systems–to organize and tag these materials, making them easier for future users to find and use. Partnering with librarians could also be important in the service of fostering cross-institutional collaborations that could potentially expand the institutional reach of writing centers.

Our analysis above suggested that oral histories can be useful for strategic planning, training, programming, and institutional memory. Discussions with writing center administrators who have access to writing center archival material have revealed to us that such material is indeed useful. Cary Smitherman Clark, for instance, oversees oral histories as part of the Writing Center Research Project. She believes that this material is useful to both tutors and directors. For tutors, especially new tutors, archival material gives context and a sense of what they are stepping into. For directors, the material can help inform staffing decisions and help buttress demands for funding, because arguments for funding can be made through real experiences. Additionally, these materials can serve as a recruiting tool for administrators and tutors alike.

Brownwyn Williams and Tim Johnson, past and current directors of the University of Louisville Writing Center, made similar observations about their use of oral histories. Both Bronwyn and Tim found that oral histories were particularly useful for understanding the development of on-campus programs, such as dissertation writing retreats, and community partnerships. Collaborations with community partners, in particular, often face high turnover on both sides. As Stacy Nall (2014) has noted, this can make it challenging to trace the development and strategies of these programs. When staff at the University of Louisville were developing new community writing projects, Bronwyn pointed them to the center’s oral histories to gain context. Tim also found these histories helpful to understand how community partnerships came about and to bridge gaps in institutional knowledge among staff turnover.

Like Cary, Bronwyn and Tim both emphasized the utility of oral histories for building long-term institutional narratives. As Bronwyn noted, writing centers often need to “continually re-institutionalize” themselves and make the case for funding and staffing to university-level administrators. Oral histories can provide directors with more narrative details about why programs were developed in certain ways, how they have met campus needs, and their impact over time. This may be especially important for new writing center directors. Tim, who began serving as writing center director in 2023, explained that the writing center’s oral histories helped prevent the loss of institutional knowledge. By consulting those histories early in his term, he learned from stories by past administrators about “what didn’t work” and “how they thought,” in a way that encouraged experimentation and trying things out, rather than only seeing the final product of successes. “For me,” Tim reflected, “the oral histories gave me a picture of decision making. . .but also, in our history, the things that had and hadn’t worked.” By inheriting this institutional knowledge, he was also able to speak to external administrators in the university and answer questions about the writing center’s long-term work.

Cary, Bronwyn, and Tim represent some of the few writing centers that have made substantial use of oral histories. They demonstrate that these materials can be advantageous for consultant professional development, programming, strategic planning, and advocacy for funding and resources. These are illustrative examples of how oral histories can serve as practical administrative tools and also enrich the experience of writing center work for professional staff and student consultants.

Conclusion

Writing centers have been a regular feature of American colleges and universities for over half a century, and we join the call for a more systematic collection of materials— digital, print, and oral— in order to preserve the institutional memories of these important institutions. Oral histories, such as the ones analyzed in this article, are a valuable tool to incorporate the voices of individual staff and consultants within our institutional histories. In addition to the practical benefits that these histories can serve for strategic planning and development, they also affirm the value of writing center staff and their experiences. Amidst challenges of staffing limitations and turnover, oral histories pause to reflect on and preserve individual narratives and insights into writing center work. By creating and using oral histories and other archival materials, writing centers can create communities that span generations of staff and affirm that their staff are worth listening to.

References

Austin, R. (2020). The Reifying Center Archive Process: Sustainable Writing Center Archive Practice for Praxis, Research, and Continuity [Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University]. ScholarWorks. https://doi.org/10.57709/12493204

Azima, R. (2022). Whose space is it really? Design considerations for writing center spaces. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 19(2). https://www.praxisuwc.com/192-azima

Best, K. (2018). Writing center + ESL program: Collaboration in support of multilingual Writers. Another Word. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/writing-center-esl-program-collaboration-in-support-of-multilingual-writers/.

Borchert, J. (2024). Outer and inner space: How a space change impacted consultants. ECWCA Journal, 0(1), 39-56.

Boquet, E. “Our little secret”: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463-482. https://doi.org/10.2307/358861

Carino, P. Early writing centers: Towards a history. The Writing Center Journal, 15(2), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1279

Carbajal, I.A. & Caswell, M. (2021). Critical digital archives: A review from archival studies. The American Historical Review 126(3), 1102–1120. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhab359

Denny, H. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Utah State University Press.

Eng, E. (2024). The Duke common data set. AdmissionSight. https://admissionsight.com/duke-common-data-set/

“Enrollment trends.” IIE Open Doors. https://opendoorsdata.org/data/international-students/enrollment-trends/

Haltiwanger-Morrison, T. (2021). A balancing act: Black women experiencing and negotiating racial tension in the center. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1960

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: A critical examination of race, place, and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2). https://www.praxisuwc.com/162-lockett

Lu, J. and Penner, M. (2024). Duke admits record-low 4.1% of RD applicants to Class of 2028, overall acceptance rate 5.1%. The Chronicle. https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2024/03/duke-university-admissions-admits-record-low-4-1-regular-decision-applicants-class-of-2028-overall-acceptance-rate-5-1-early-decision-supreme-court-ruling-undergraduates.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. University Press of Colorado.

Nall, S. (2014). Remembering writing center partnerships: Recommendations for archival strategies. The Writing Center Journal, 33(2), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1771

Natarajan, S., & Morley, P. (2020). Threads, woven together: Negotiating the complex intersectionality of writing centres. Discourse and writing/rédactologie, 30(1), 43-61. https://doi.org/10.31468/cjsdwr.801

“Oral History Best Practices.” Oral History Association. https://oralhistory.org/best-practices/#:~:text=Four%20key%20elements%20of%20oral,of%20one%20or%20many%20interviews

Purdy, J. P. & DeVoss, D.N. (2017) Making space: Writing instruction, infrastructure, and multiliteracies. University of Michigan Press.

Rentscher, M. & V. Kennell. (2018). “Getting to the roots of L2 writers experiences.” Another Word. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/writing-center-esl-program-collaboration-in-support-of-multilingual-writers/

Sicari, A. R., Naydan, L. M., & Efthymiou, A. (2021). Faith, secularism, and the need for interfaith dialogue in writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 191-210. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1963

Smitherman, C. (2003). “Conducting an oral history of your own writing center.” Writing Lab Newsletter, 27(10), 1-4. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v27/27.10.pdf

“Student Enrollment, Fall 2024.” Purdue University Undergraduate Admissions. https://admissions.purdue.edu/academics/enrollment.php

“The Writing Center at Michigan State University’s Oral History Research Project.” Michigan State University. https://onthebanks.msu.edu/Object/162-565-7095/Writing-Center/

“Writing Centers Research Project.” University of Central Arkansas Center for Writing and Communication. https://uca.edu/cwc/wcrp/

“Writing Resources.” Thompson Writing Program, Duke University. https://twp.duke.edu/twp-writing-studio/resources-students

Zammarelli, M. & Beebe, J. (2019). A physical approach to the writing center: Spatial analysis and interface design. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/a-physical-approach-to-the-writing-center-spatial-analysis-and-interface-design/

Footnotes

- We chose to focus on these two institutions because of our former affiliations with them. Woolley worked as a Writing Studio consultant in 2017 and 2019 and taught a course through the TWP in 2020 as a graduate student at Duke. From 2022 to 2024, she was a postdoctoral research associate at the Purdue Writing Lab. During her time as a graduate student at Duke University, Allain worked at the TWP intermittently between the years 2018 and 2023 in various capacities, including as a Writing Studio consultant. It should be noted that we do not speak on behalf of either the TWP or the Purdue OWL in any official capacity.↩