Maria Isabel Galiano, Florida International University

Xuan Jiang, Florida International University

After brainstorming what to post about on our Writing Center’s Instagram for International Women’s Day, one thought came to mind. I wanted to spotlight Dr. Xuan Jiang as she has had much impact on my and other tutors’ lives, both personally and professionally. In only one afternoon, I was able to collect 14 written testimonies via email from eager tutors who wanted to be involved in spotlighting.

—Maria

Introduction

A single Instagram post can capture more than a moment—it can reflect a network of relationships, care, and growth. This article, in its form of cross-inquiry between a peer tutor, Maria, and a writing center administrator (WCA), Xuan, starts exploring the untold story of and behind an Instagram post. The Instagram post was designed by Maria, featuring Xuan’s co-mentorship and collaborations with 15 tutors through their voluntary testimonies. Inspired by the Instagram testimonies as the showcase of those individuals’ growth, we delved into our own stories connected with this post. Building upon the theoretical framework of feminist ethic of care (Wenger, 2014), we conducted duoethnography through individual narrations and reflections as well as Zoom interviews for dialogic storytelling (Norris & Sawyer, 2012), aiming to answer the following research questions: How does the WCA-tutor co-mentorship and collaborations scaffold the growth and empowerment of peer tutors, many of whom are L 1.5 writers? How does social media amplify such an impact happening within the WC and spreading over to student writers at the institution?

Many writing centers (WCs) hire peer tutors, which positions WCAs in a potentially dual role of academic and professional mentors. Their academic mentorship, if available, starts from a tutor-training class, and the professional mentorship continues at the WC as a workplace. Although there are studies in general sharing peer tutors’ academic and professional takeaways and growth (e.g. Hughes et al., 2010; Hutchinson et al., 2023), studies with specific institutional contexts (e.g. Hispanic-Serving Institution) and staff population (e.g. L 1.5 writers) would advance the pluralistic facets of this topic. L 1.5 writers, as described by Liliana M. Naydan (2016), include members of the first generation in their family to speak English as a first language, or writers whose language-use patterns deviate from the expectations of Standard Edited American English (SEAE). This article adopts the term L 1.5 writers to reflect a wider scope, encompassing multilingual and international students, monolingual speakers with non-SEAE uses beyond classrooms, and first-generation college students.

As researchers about L 1.5 writers and L 1.5 writers ourselves, we thread the Instagram post snapshots with our reflexive journals of developing, designing, and reading this post, exploring a WCA’s mentorship as an action of feminist ethics of care and its reciprocal impact of mutual empowerment for L 1.5 writers serving as the writing center staff. We both decide to organize and present our findings as a cause of actions, metaphorically called a “treasure hunt,” as we emphasize the unexpected and abundant discoveries along with our research journey, very akin to the essence of duoethnography. Like treasure hunters charting unknown terrain, we follow clues in our narratives and artifacts, uncovering connections that might have otherwise remained buried, each of which prompts new questions and shares meaning-making.

The significance of this article is tri-fold: a reminder about the importance and synergy of reciprocal mentorship between WCAs and peer tutors, a showcase of Instagram as a public-facing (mainly student-facing) social media platform to represent such a multifaceted relationship and the writing center as a writers’ community, and an urge to complicate writers’ identifiers and foreground L 1.5 writers to better understand and more effectively serve student writers. With this knowledge and awareness, peer tutors and WCAs may find notable ways of connecting with one another and bringing in new perspectives into WC praxis.

Theoretical Framework: WCAs’ Feminist Ethic of Care

The term feminist ethic of care refers to “a moral and egalitarian means of leadership, one that spreads out rather than reaches up” as “a means of flattening hierarchies and redefining professional relationships” (Wenger, 2014, pp. 120-122). Accordingly, power under such leadership “is shared and facilitative, built through relationships and governed by support[,] not control” (Wenger, 2014, pp. 122-123). This brings the needed role played by WCAs not only as leaders in disturbing the dominant structure (Blair & Nickosen, 2018) by building flattened hierarchies (Huseby & Thierauf, 2023) but also as mentors in supporting peer tutors.

Seeing the pivotal role of WCA’s feminist ethic of care in steering WCs as shared space, we decide to coin this term as a lens to look at one direction—concrete collaborative practices of WCAs and peer tutors with respect to their outcomes, processes, population, and public-facing channels through social media, as detailed below in the literature review.

Literature Review

We start our literature review from the co-mentorship and collaboration of WCAs and peer tutors, as we see it as the impetus strengthening WCs’ productivity and fueling WCs’ outreach. Then, we continue with the impact of such collaborative mentorship in three directions: professional, scholarly, and institutional. In addition to the three conventional paths, we add social media as the other venue to enhance WCs’ visibility. We conclude this section with a key concept—L 1.5 writers, a term referring to the population vital to the significance of our study.

Co-mentorship of WCAs and Peer Tutors

We believe it is pivotal to redefine mentorship in a way that benefits all individuals involved in collaborative processes and lends to feminist co-mentoring. There needs to be a clear definition of mentorship where the environment is shaped to support “horizontal feminist co-mentoring” where guidance can come from any individual, including reciprocal mentoring between WCAs and peer tutors (Godbee & Novotny, 2013, p. 192).

In many cases of training peer tutoring through curriculum, WCA-tutor mentorship is the continuation of instructor-student relationships in the WCs, further reforming the teacher-student power asymmetry or Brian Huot’s “decenter[ing] the writing classroom” (2002, p. 169). Hence, learning takes place formally (i.e. structured professional development), informally, and even incidentally (i.e. hallway conversations) (Huseby & Thierauf, 2023). To encourage such learning to continue and come to fruition, WCA-tutor mentorship and collaboration can be, at least, the starting point. Mentors can share calls for proposals, offer strategies for academic conferences, assist students with publishing processes, and introduce their mentees to their networks (Moore et al., 2022).

Between WCAs and peer tutors, mentorship and collaboration advance the definition and practice of research with knowledge of “empirical methods and the ethics of human subject research” (Fitzgerald, 2022, p. 28). Such a statement was supported by Emma Saturday, a peer tutor mentored by her WCA, with respect to “the critical thinking and writing skills” as she learned through her English program and via peer tutoring where she constantly engaged with “thinking and information drawn from sociology, linguistics, rhetoric, and other fields” (2018, p. 27). Moreover, the one-on-one WCA-tutor mentorship “supports ongoing communication about—and enthusiasm for—research” (Moore et al., 2022, p. 19).

Multi-layered Impact of WCA-Tutor Collaborations

Many WCA-tutor coauthored publications emerge in writing center studies or in general writing studies (e.g. Fishman et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2022), and more broadly, their WCA-tutor collaborations have exerted a synergistic and phenomenal impact on not only themselves but also WCs and university members. Here unfolds three dimensions of the impact: professionally, scholarly, and institutionally.

Professionally, many scholars call for collaborations between WCAs and peer tutors, such as Patricia Haney (2020) who signified such practice as a way to shift the hierarchical dynamic at the writing center. In order to bridge the gap between WCAs and peer tutors and redefine what professional development means, Haney emphasizes how allowing tutors to co-create and lead professional development opportunities cultivates a feeling of shared authority and mutual trust. Further, a study from peer tutor Saturday found that because of her WCA-tutor collaborative research, she “was not only helping [the students she worked with] grow as writers but pushing them to think in new directions about their identities as students” (2018, p. 27). The self-perceived identity change does not only happen to peer tutors but also to WCAs. Sharing parallel vulnerability and contingency, WCAs’ experiences may be similar to those of peer tutors in more ways than expected. This article addresses the marginalized status that many WCAs may hold, compared to other tenure-track or non-tenure track faculty who appear to have a higher standing professionally (Brooks-Gillies & Moore, 2024). Stephen North (1994) notes the feeling that WCAs encounter as if they are regarded as “lower in institutional pecking orders” as opposed to lecturers (p. 13). The advocacy of institutional equity for WCA efforts may shed light on some of the experiences peer tutors go through personally and academically, lending a hand in the similarity both parties may face. Through this distinctive perspective, WCAs may assist peer tutors in developing their professional agency while supporting and affirming the expertise that peer tutors manifest in the writing center field.

Scholarly, there have been calls for tutors’ voices to be heard in writing centers and for connections to be made within the staff. Opportunities for peer tutors and WCAs to work together can benefit both parties and have an impact on the research community and pedagogy (Efthymiou & Fallert, 2022). The connections being made can expand farther to cultivate a culture of academic conversations, helping all WC staff find ways to strengthen their academic and professional portfolios. Collaboration stems from various areas in the writing center field, greatly impacting how individuals interact with one another whether they are WCAs or peer tutors. There may be instances where a WCA and peer tutor find research interests that align and, therefore, it benefits both parties to work together and build on each other’s knowledge. These connections travel “across institutional hierarchies” where they may lead to these individuals finding common ground (Efthymiou & Fallert, 2022, p. 640).

Institutionally, the WCA-tutor collaboration, for instance, told from the point of view of a librarian exemplifies how peer tutors and WCAs can connect with other members and facets of the university setting (Zauha, 2014). With the creation of the university-wide event WriteNight, Janelle Zauha (2014) discusses an event where librarians, peer tutors, and WCAs all come together multiple times a semester to assist student writers with all stages of the writing process. In this activity, different divisions of the university come together to focus on the joint goal of helping students improve their writing, covering the stages and aspects of writing: brainstorming, researching, and citations (Zauha, 2014). It sets up a comfortable space for casual conversations about academics, allowing all members involved to learn from one another and to adapt unique ways of creating bonds. This may lead to discussions amongst not only peer tutors and WCAs but also faculty in other departments that may bring in a new perspective and challenge the common structure for communication.

Besides the three dimensions of the impact of such co-mentorship and collaborations, peer tutors in our WC utilize social media to share uplifting updates with our student population, seen in the next section.

Instagram as Student-facing Platform of Writing Center Praxis

While much of the existing scholarship frames writing center social media—particularly Instagram—as a promotional tool or an addition to their marketing strategy, it can also open doors to be reimagined as a “digital extension of universities” (Bales & Dunaway, 2019, p. 156). This idea of viewing social media as a “digital extension” allows peer tutors to contribute to the WC’s identity and community-building more actively, presenting the WC as a collaborative space—not just for writing but also for the representation and co-construction of its public narrative. Integrating peer tutors into the process of content creation of social media at WCs can amplify student voices in ways that shape and humanize the center’s public narrative. Peer tutors are students too and, therefore, share the unique aspect of navigating both academic and tutor roles, which in turn, offers them unique insight into how to best make posts fun and meaningful for the student body (Bales & Dunaway, 2019). This affirms the notion that peer tutors are uniquely positioned to create content that truly resonates with students. By centering student voices in a WC’s outreach, peer tutors are not just promoting writing support; they are inviting all students into a space that already belongs to them.

In regard to engagement, visual elements, like photographs, play a key role in boosting interaction with image centered posts on Instagram generating significantly more interaction than text-only content (Crowley-Watson, 2019). These images help rhetorically promote the WC by celebrating its staff—peer tutors, WCAs, and even alumni—thus encouraging broader participation and sustained connection (May, 2022). As many centers adapt to hybrid or virtual spaces post COVID-19, social media has become a vital space for tutors to engage with the WCs and be involved in the center’s community. Amanda May (2022) notes that the COVID-19 pandemic “drastically altered tutoring pedagogies and labor conditions,” thus forcing WCs to reconsider how they remain visible and connected to students during remote operations and in the aftermath in more hybrid spaces (p. 83). As a response, platforms like Instagram provide a virtual space for tutors to create discourse with the student community through activities, such as sharing events, celebrating each other’s work, and co-creating content that reflects the evolving WC culture and enhances the WC’s visibility. Florida International University’s Center for Excellence in Writing, for instance, tries to prioritize Instagram as the main social media with weekly updates, as Instagram is the most popular social media among the FIU student body. This practice is feasible to avoid overburdening staff who volunteer working on social media and keep our CEW visible and reliable through its posts. This kind of intentional presence online allows the center to stay connected with the broader university community, even in moments of physical disconnection.

As seen above, members in this virtual and in-person community through active collaboration or subconscious immersion can benefit in this multifaceted, academic ecosystem. We argue that some student writers, elaborated below as L 1.5 writers, would benefit even more.

L 1.5 Writers as the Majority in this Institutional Context

Liliana M. Naydan’s (2016) points out that many so-called native users of English are actually L 1.5 writers, members whose language-use patterns deviate from Standard Edited American English (SEAE). From our own experiences as L 1.5 writers, we both experience the process and toll of linguistic marginalization with deviation from the expectations of standard English (Herzl-Betz & Virrueta, 2022). Beyond writing, our upbringing (e.g. working class, immigrant families, and speaking other languages and dialects outside of the classroom) does not prepare us for hidden curriculum, implicit instruction, and untold expectations in school and college (Delpit, 2006). McCrory Calarco exemplified the hidden curriculum as “how to do, write about, and talk about research” and “how to navigate complex bureaucracies” (2020, p. 2). Having not been explicitly taught these, we have been “other people’s children” (Delpit, 2006), seen as unprepared, deficient, and unteachable, until we empower each other.

Now acting the role of a WCA and a peer tutor, we see and enjoy our reciprocal benefits academically and professionally in our WC community, and we strive to empower more L 1.5 writers. L 1.5 writers, as we two believe, represent a predominant student population in this large urban R1 Hispanic Serving Institute (HSI). The HSI has a diverse student population: 65% Latinx, 12% Blacks, 10% Whites, and 3% Asians (Robertson, 2022). Besides its racio-ethnic diversity, the 55,000-student population includes 33% first-generation students (Florida International University – Digital Communications), 58% Pell grants recipients (Florida International University – Digital Communications), and 92% commuters (Florida International University Student Life – US News Best Colleges). We argue that L 1.5 writers (in our context referring to both tutors and tutees) are abundant in their language repertoires and life experiences across cultures, languages, and accents. Their lived knowledge, once recognized, would enrich the collective funds of knowledge at the institution and in fields.

To help students become better writers, it is important to know the unique assistance provided for L 1.5 writers from the perspective of WCAs and peer tutors. Our added connection as L 1.5 writers ourselves can naturally contribute to our transcultural backgrounds and translanguaging approaches to WC praxis for diverse student writers (Thonus, 2003). The WC at our HSI offers a supportive environment for student writers while fostering an inclusive atmosphere to acknowledge the strengths and challenges of these L 1.5 writers. Such acknowledgement is seen through but not limited to WCs’ social media, exemplified through Instagram below.

Methodology

We employed duoethnography for the current study, reflecting relational and reciprocal collaboration between a WCA and a peer tutor. Driven by our research questions, we chose duoethnography as it embraces individual narrations and reflections of us as L 1.5 writers with marginalized and silenced experiences; moreover, it values dialogic intimacy (Valdez et al., 2022) and dialogic storytelling (Norris & Sawyer, 2012), which in our study took place as Zoom interviews. Foregrounding personal connections and individual feelings to academic and professional arenas of writing centers, our study was strengthened by employing duoethnography as it combined personal and collaborative views through critical and relational dialogues.

Our Exigencies

Besides our common identifier as L 1.5 writers, we share our individual feelings relevant to the Instagram post here in order to better position ourselves in the duoethnographic explorations.

Maria’s exigencies lie in her desire to propel the voices of peer tutors and examine the effects that a critical mentorship may provide both parties: peer tutors and WCAs. Her focus for the Instagram content derived from promoting the WC to student writers and making peer tutor voices heard, many of whom are L 1.5 writers. Through highlighting Xuan in an Instagram post regarding International Women’s Day, her aspiration was to feature the impact a WCA’s contributions and inspirations have on peer tutors in a light that is not typically explored.

As the highlighted individual in the Instagram post, Xuan humbly agrees with the deeds peer tutors listed and appreciates their recognition in this public-facing social media platform. Xuan’s long-term drive in establishing such equitable and reciprocal mentorship roots in her belief in a rapport mechanism built within the WC but extending beyond the WC through peer tutoring. Xuan refers to empowering grassroots’ voices and thoughts from bottom-up as the means to the end—flattening top-down power structure in academia.

Data Collection

Building on the parameters of Natali Valdez et al. (2022), we developed our protocol of duoethnographic exploration after our first meeting to start this co-authoring journey in Summer 2024. That summer was Maria’s last semester at the Center for Excellence in Writing (CEW) as an undergraduate tutor before pursuing her master’s degree and being a graduate assistant at Florida International University.

We each wrote our individual anecdotes and narratives by retrieving our memories related to the Instagram post independently, Maria as the designer and testimony provider and Xuan as the reader and spotlight. To provoke our lived stories about the aforementioned topic as data in this study, we also prepared a list of interview questions respectively prior to our interviews.

Nevertheless, follow-up questions or other spontaneous questions out of intuitive curiosity were filled in along the process of the interviews (Valdez et al., 2022). During the interviews, we decided to take shift in asking questions with the flow of our dialogue. After reflecting on those questions and answers as well as watching the whole recorded video of our first interview, we wrote our reflections on our own Word documents and developed second-round questions for the second virtual conversation. At the end of the second recorded interview, we reached the point where we had no more questions about our shared thoughts and deeds. Then we concluded the data collection process. We both sensed our dialogue went from the surface to the core via conversations—feministic, dialogic, relationship focused, and inquiry based (Cox & Riedner, 2023, p. 15). We also felt that our relationship grew dialogically intimate not only seen from the audios and notes but also felt by us inside. The data collection process itself to us is a journey of co-mentorship.

Thus, our data collection started with anecdotes about the Instagram post instinctively provoked as storytelling. The data also includes answers to those questions about the Instagram content, mentorship defined and received, and backstage stories about the Instagram post during the two virtual interviews. Last but not least, our individual notes and reflections cross inquiries before, during, and after the two virtual interviews complement our data.

Data Analysis

Our data analysis started with our individual observations, analyses, and reflections on the first recorded virtual interview. The outcomes of the primary analyses steered the second virtual interview. We continued with individual notes and reflections subsequent to the interviews. After individual data analysis and during our continuous post-interview meetings, we pooled analyses and collaboratively inquired and reflected on each other’s notes and reflections by asking further relevant questions. Through cross inquiry and mutual agreement, we integrated our notes to identify themes which echo with our research questions and existing literature (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

We co-wrote about these themes, individually written on a shared document differentiating our agentic voices with our preferred text colors and collaboratively consolidated through regular meetings. During our meetings, we discussed our written content to make decisions for the co-authoring manuscript and assigned ourselves to the upcoming tasks. Maria took the lead in the data about social media because she was deeply positioned in the topic; Xuan took the lens of feminist ethic of care and reread the data about co-mentorship and WCA-tutor collaborations. We each decided what analyses to write on our own for the best of this manuscript, keeping in mind to reach an overall balance of descriptive, interpretative, and reflexive accounts (Braun et al., 2022). Our virtual meetings were set up to discuss our analyzed data as critical readers and to conceptualize themes (Braun et al., 2022). Through conversations of cross-inquiries and collaborative reflections presented through our “treasure hunt,” we felt “the treasure map” (as we metaphorically referred to our analyzed data) was deeper and clearer. Meanwhile, we co-wrote our manuscript by revisiting the theoretical framework, literature review, and our research questions. With mutually agreed data representation and completion of our first draft, we believed that we reached the point of data consolidation and triangulation to enhance the richness and trustworthiness of findings.

Findings Deriving from Our “Treasure Hunt”

Our findings follow the original discovery path, showcasing the reciprocal mentorship from the tangible to the core. This section starts with our anecdotes about the post (see Figure 1), continues with our agentic experience in social media and WC work, and concludes with the re-merge of WC work showcased in Instagram, as the treasure we both metaphorically refer to.

Figure 1

Glimpse of Instagram Post: Slides 1 & 3

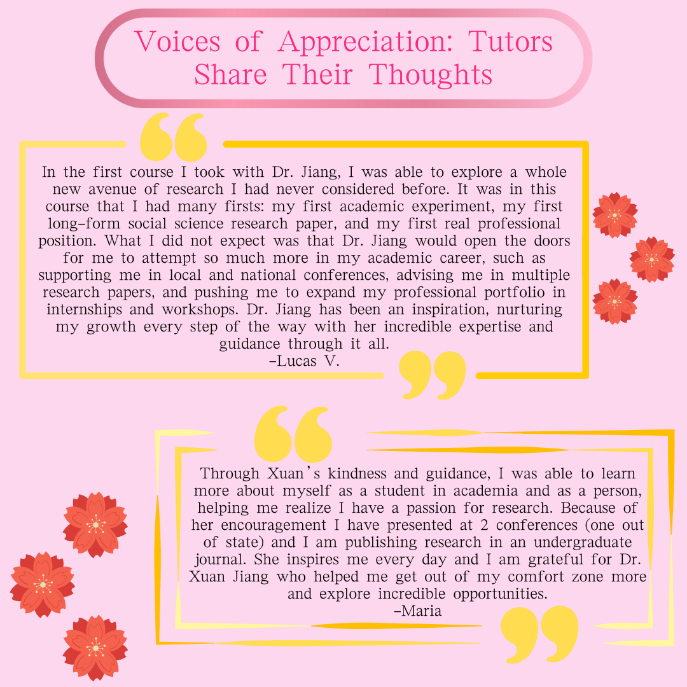

Maria’s anecdote: When I realized that International Women’s Day was coming up, I knew that I wanted to make a post that would spotlight Dr. Xuan Jiang, as she has been an impactful figure in not only my time at the writing center but for numerous other tutors. I sent out a mass email that included every peer tutor asking them to fill out a Google Form if they had the time and were interested. I shared with them that I wanted to spotlight Xuan. I received 14 responses from enthusiastic peer tutors who expressed with me, both in person and through email, that they loved the idea of making a post for Xuan.

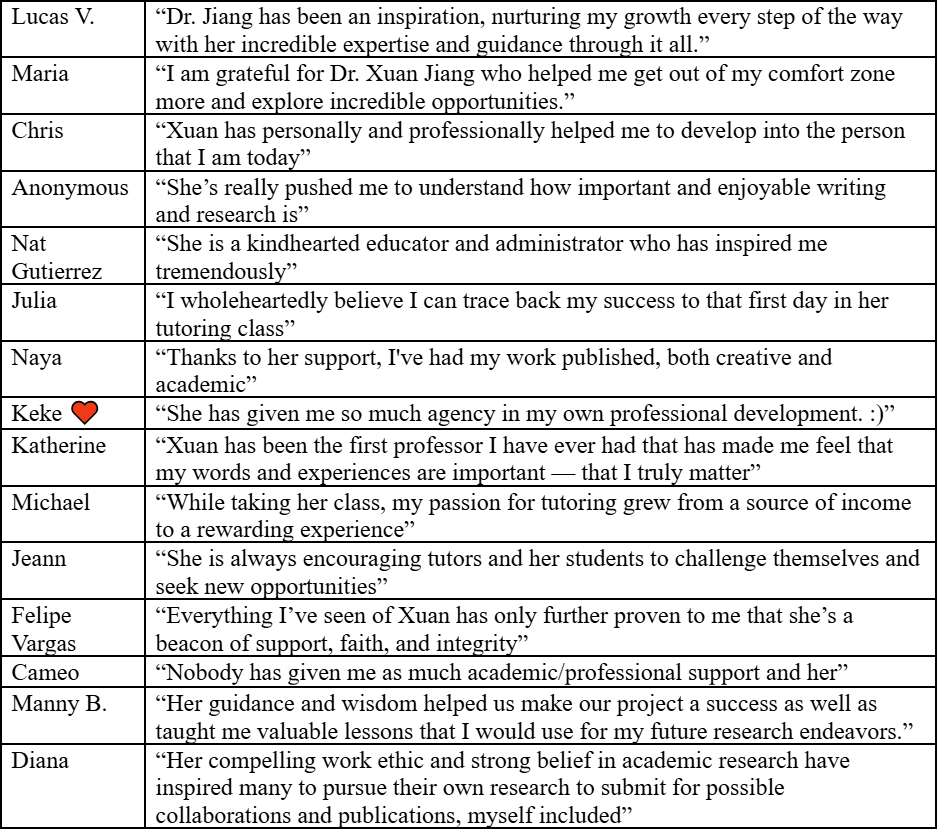

The Instagram post highlights the connection between WCAs and peer mentors with highlights of their testimonies in Table 1 and full testimonies in the Appendix.

Table 1

Glimpse of Student Testimonials

Xuan’s anecdote about the Instagram post: As a novice Instagram user who follows only two users, I did not realize that I could flip right to see more pages of an Instagram post. Two months later after I noticed the Instagram post about myself, I eventually found and read 14 testimonies of peer tutors in the SAME post! By simply flipping to the right, it was like one day I found a treasure box and weeks later I discovered the treasure box was a music box. What a double joy I was honored to have (See Figure 2 below).

Figure 2

A Treasure Box

Inspired by Xuan’s metaphorical narrative of her experience discovering this Instagram post, we both decided to position ourselves as “treasure huntresses” to share the subsequent findings of our untold stories.

Maria as a Huntress for her Instagram Post Treasure

One of my first encounters with the Center for Excellence in Writing (CEW) social media was hearing the WC director—during a staff meeting—ask if anyone wanted to volunteer to work on the Instagram account. As the staff meeting continued, ideas started to swirl in my mind. Visions of my creativity shining through challenged myself to accomplish things I’d never done before. At the time, I had been looking to get out of my comfort zone more socially and practically—and this was the perfect opportunity for it. However, it was more than just that. I sought to give back to the WC and help contribute to it in any way I could. The WC was a beacon of hope for me when I was looking for purpose and a way to quantify my passion for writing. With its community and support system, I was truly able to grow, not just as a tutor but as a person, learning more about myself in this academic, welcoming space, as I found the motive to write more, not only for myself but for writing center fellows who care about me. I wanted to show others what a wonderful place the WC is and could be for many individual students, and the best way for me to do so was to promote it through Instagram which I had some previous experience with.

After discussing with one of the WCAs, I got access to social media and started working. The first graphic I ever posted was on the kinds of writing that the CEW helps with.

As time went on, I gained more insight on best practices for posting and what kind of graphics and images did best. When focusing on the design I “try to express myself . . . I try to make them more like colorful and creative something that like can engage with students” (interview in June 2024). I started to note that posts with images did really well compared to posts that maybe only had information on them. Whenever there was a post that included either an image of a tutor or a group picture from a conference, we were likely to get more engagement on the post in the form of likes, or even comments and shares. Such that, a post regarding World Book Day garnered one of our highest likes at the time and presented several images of tutors and receptionists reading books. I was always sure to incorporate vibrant colors and fun fonts in order to grab the audience’s attention. In addition to this, I found that Instagram reels caught people’s attention. The main focus of the two Instagram reels I had was on the WC plushies we had exploring different parts of campus. My aim with this idea was to make the writing center a core part of college life; showing that while we could be serious and help with assignments, it was also a friendly and welcoming environment to go to.

Something I noted throughout my time posting was the encouragement the posts received from Xuan through the comments section. On a post I made on February 13 about “Top 5 Tips for Critical Thinking Skills,” she commented saying they were great tips for writers and thanked the CEW Instagram. Again, on June 13, I tried my hand at a different style of post—an Instagram reel—featuring some of our beloved WC plushies visiting different spots on campus, and Xuan commented with encouragement, saying “Love it! Cutest video ever :)” in the comments section. A third time, July 19, I created a post for the “CEW Tutor of the Month”—sharing images, fun facts, and a quote from the tutor—and Xuan can be seen in the comments section congratulating the tutor.

Xuan as a Huntress for her WCA-tutor Mentorship Treasure

Years before the WC had its Instagram account, I started to ask myself what it is like to be a WCA. Shared in the conversation with Maria in June 2024, I admitted “first, kinda negate myself, because I know I am not professional enough. I don’t want to be seen with power.” After emptying myself with all those default features as an administrator, or WCA, I sought to discover my own definition of professionalism and followed Shapiro’s notion—Critical Language Awareness with the two prongs progressive-pragmatic (2022). I realized and confirmed the two prongs in my WCA’s role as that “being personal is part of being professional.”

Not only have I secured myself with my own definition of professionalism as a WCA, but I have also harvested a big number of publications with peer tutors through collaborations and co-authorship. Over six years of being a WCA, I have had 18 publications, among which 4 as collaborations with undergraduate tutors and 6 with graduate tutors. We together study our praxis and publish; we advance our praxis through research.

Such intensive and extensive scholarly collaborations have transformed the WC into a site of peer learning and collaborations. The tutoring schedule can be used as meetups between WCAs and tutors as well as tutors and tutors which offers an abundance of one-on-one contact points; the takeaways from ongoing readings and literature can be discussion points; the noticing from tutoring praxis can be talking points; the staff meeting can highlight achievements and carry rewarding momentums.

In terms of WCA-tutor mentorship beyond collaborations, I see my interactions with tutors as an approach to “transgress the definitions of colleagues and friends, flatten the hierarchy between teachers and students or WCAs and tutors . . . inviting everyone to participate [as much in the collaborations] as possible” (interview in June 2024).

Both for the Instagram Post about WCA-Tutor Co-Mentorship Treasure

Maria discussed how “I even got emails back with people telling me how great it was that I was doing this for Xuan, and how she totally deserved it” (interview in June 2024). The peer tutors were thrilled to have this opportunity to share their thoughts on Xuan and how much of an impact she had made in their lives. This was something Maria could highly relate to as she stated: “Xuan has been such an impact for me ever since I took her class” (interview in June 2024). Emotionally connected, Maria decided to participate as a testimony provider, in addition to her role as the Instagram post designer. While Maria was the one creating the post, she felt strongly about Xuan’s impact in her life and wanted to be a part of the voices sharing their testimonies. She felt that Xuan’s mentorship had been pivotal in shaping her academic and professional journey but also her personal motivations and dreams. Maria also hoped to inspire others to seek out meaningful connections in their own educational paths. She felt that Xuan’s unwavering guidance and encouragement deserved to be highlighted, and she wanted to be a gear in this music box.

Viewing the Instagram post, Xuan felt her emotional support vividly from peer tutors publicly and loudly as her years of devotion to student research and redefining WCA-tutor mentorship got recognized by peer tutors, the other party. More importantly, Xuan noticed that, “[Peer tutors] share one of the common messages that their first presentation was with Xuan, or because of Xuan” (interview in June 2024). These tutors’ first co-presentation and further co-authoring publication experience with Xuan as a seed has yielded more scholarly activities of their own—conference presentations, fellowship applications, graduate studies, and leadership roles.

Discussion

Our discussion converges the vantage point of reviewed literature and analyzed data through the theoretical lens of a feminist ethic of care. Corresponding to our two research questions, we organize this section into two components: one focusing on how social media elevates the agency of people in our WC and the WC itself, and the other highlighting collaborations and co-mentorship as the WC’s impetus driving the growth of WC individuals many of whom are L 1.5 writers.

Amplifying Contingent Agencies through Social Media Posts

Social media has become essential to represent what WCs are and what WCs can do, especially after 2020 when COVID-19 broke out. As many WCs transitioned to fully online services, the digital sphere became more than just an extension—it became a necessity to stay connected to students (May, 2022). As Kristen Bales and Billie Jo Dunaway (2019) note, social media platforms now function as digital pathways to connect students and amplify their presence within the university community. Maria, utilizing her digital literacy skills and strategic communication during working hours, amplifies such advancement on the students’ most used social media—Instagram. One of the vivid themes Maria focused on in the interview was to highlight our WC and our WC individuals, rewriting the default image of our WC with a plethora of talents and knowledge as a collective of students, a multitude of cultures and languages within WC staff and student writers, and a sense of belonging via tutor-led student-centered weekly events and routine tutoring service.

WCs are not only the nexus of students’ writing campus-wide but also the pioneer in social changes, in particular, to facilitate structural changes in society, disciplines, and the institution itself (Inoue, 2016). We believe WCs still carry such missions; our WC being one of them. Streamed through the interactive channel on Instagram, our WC showcases feminism, linguistic justice, vocalization of students’ knowledge as well as other overlooked assets through rhetoric display and interactive features. Maria’s Instagram strategy reflects this ethos by uplifting voices from within and representing the WC through the very students it serves. In this way, our center resists top-down branding and instead leans into authentic, peer-driven communication. Peer tutors are uniquely positioned to do this work as “their authentic voices guide our messaging” (Bales & Dunaway, 2019). This kind of authentic, student-centered engagement is not only impactful—it’s also sustainable when approached intentionally. May (2023) discusses how writing centers with limited resources can maintain social media presence through tools like Canva, weekly posting schedules, and tutor-led teams. Maria’s leadership reflects this balanced model. As the person running the account, Maria developed not only technical communication skills but also a stronger sense of voice and purpose. It helped her see her own identity and bilingualism not as limitations but as assets to center in our messaging. For future tutors, seeing peers like themselves running these platforms offers a roadmap for authentic advocacy. It demystifies the process and shows that their lived experiences are valid and needed in public-facing representations.

The WC Instagram, run by and for tutors, provides a platform for tutors to manifest their dual roles. As L 1.5 writers themselves, many of our WC tutors now “see themselves as writers with the ability and even responsibility to write for action in the world” (Godbee et al., 2015, p. 5) by advancing an approach to bridging their identity work and academic work. Highlighting their assets as L 1.5 student writers, tutors using their professional roles as peer mentors lead student-centered weekly conversation circles in Spanish, English, Japanese, Mandarin, and Haitian Creole (before). This multilingual presence on Instagram not only validates the linguistic practices of our student population but also signals a more inclusive and responsive WC ethos. It communicates to multilingual students that their voices and home languages are embraced in academic spaces. They advance anti-racism and linguistic justice work in writing center studies and writing studies through praxis at the frontline of constant interactions with students.

Leading from Individual Vulnerability to Collective Strength

Xuan has relatable identities and positionalities as an L 1.5 writer. She has experienced linguistic marginalization with the same deviation from the expectations of SEAE as her students and peer tutors (Herzl-Betz & Virrueta, 2022, p. 172). A lack of confidence in language proficiency gives Xuan the powerful tool to genuinely empathize with her L 1.5 student writers, who are also less confident and less familiar with academia. This is parallel to Xuan’s professional contingency, which echoes with writing center research about WCAs in lacking her professional pathways and protection from any faculty handbook (Brooks-Gillies & Moore, 2024; North, 1994). A lack of professional pathway gives Xuan a connection with her colleagues who are peer tutors, including Maria at the time of the study, who also feel less secure and perhaps worried with their part-time student employment situation. Being seen not just as a student employee but as a collaborator in knowledge production made Maria feel that her academic insights mattered. It built her confidence to pursue scholarly questions rooted in her lived experience.

Nevertheless, Xuan agrees with and believes in the abundance of peer tutors who can “identify their own research questions and generate insights that administrators and faculty members are not in a position to develop” (Fitzgerald, 2022, p. 28). This model demonstrates how feminist co-mentorship values relationality and care, especially for L 1.5 tutors and student writers who may otherwise be sidelined in academic knowledge-making. It shows a pathway for reimagining who gets to participate in scholarly discourses. For instance, Maria’s class paper on the effectiveness of online tutoring to writers’ anxiety was beyond Xuan’s position to conceive as a research idea. Acknowledging tutors’ funds of knowledge, Xuan has played her role as a facilitator and research project advisor in scaffolding undergraduate collaborators development of technical skills, methods, and techniques in the pre-service tutoring training class she teaches and through their collaborations (Moore et al., 2022). The collaborative fruition is tangible with multiple publications and presentations which help shape the landscape of scholarship with unrecognized knowledge from undergraduate researchers, including L 1.5 writers; the collaboration also builds the culture of academic research in the professional space for more outcomes to come.

Such collaborations transform tutors’ mindsets from thinking of research as an abstract concept or working on research projects only in course contexts to envisioning themselves as scholars who can do public-facing work in academia (Sohan et al., 2025). Maria presented her research in a humanities undergraduate research conference at the university and advanced her research interests by collaborating with two other peer tutors to present in a national peer tutors’ conference in the same year. Now Maria is a graduate student and graduate assistant in the English department, but she still comes back to the CEW and connects with staff through their reading club every week. Maria is not the only alumni tutor coming back which signifies the community this WC has been built into as a unit always advancing their collective strengths and collective impact on the landscape of academia and the institution. Moreover, Maria is one of many current and alumni tutors (e.g. individuals in Table 1) who continue to articulate their voices in scholarship, showing collective strength and resilience in academia. The synergy shared in but not limited to Maria’s testimony from one individual to many more is evidently seen and vividly felt. The trajectory from a tutor to a scholar that Maria has experienced can serve as a model for future tutors who may initially see writing center work as short term. Our collective stories show that this work can be a foundation for lasting academic and professional engagement.

Conclusion

Looking back, the co-mentorship experiences of Xuan, Maria and other tutors—brought to life through our WC’s Instagram—align with many scholars’ coauthoring journeys, exemplifying WCA’s feminist ethic of care and empowering co-writers and community members to write for action for themselves and for the world. These co-mentoring experiences foreground our agency in our projects and amplify those unspoken and unheard lived stories—stories that now gain visibility and resonance through a public, peer-run digital platform. We, researchers, are part of the change-making landscape in academia as subjects and, many times, objects of academic work and identity work. The process and outcomes are reciprocal and synergistic, vividly represented from the Instagram post as a public-facing platform and show-not-tell invitation to student writers, who might be L 1.5 writers, to join in this writers’ community as both writers and potentially tutors. Although Maria and Xuan as well as many WC tutors fall under the category of L 1.5 writers, it is not inferred that WCAs who don’t have such an identity cannot apply such a mentorship model in their own contexts.

Looking forward, Maria and Xuan plan to expand this duoethnography to conduct an IRB-approved study, further exploring the tutors’ rich stories. In doing so, we aim to better understand how digital platforms like Instagram support reciprocal mentorship and make tutor-led identity work visible, replicable, and transferable. We both believe the significance of such sharing helps find notable ways of connecting with one another and bringing in new perspectives. We envision that building such a learning and research ecosystem advances the definition of professional identities as a substantial way to change our employment contingency and counter our professional vulnerabilities. Finally, we call for WCAs to explore resources via the vision of abundance and flexibility—including the creative use of social media—and to strategically navigate these tools to foster professional spaces rooted in welcome connection and essential support. Instagram, in particular, offers a space where tutors can actively shape the writing center’s ethos and visibility one authentic post at a time.

References

Bales, K., & Dunaway, B. J. (2019). Shared voices: Writing centers and social media. Communication Center Journal, 5(1), 156-161. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1269437

Blair, K. L., & Nickoson, L. (2018). Introduction: Researching and teaching community as a feminist intervention. In K. L. Blair & L. Nickosen (Eds), Composing Feminist Interventions: Activism, Engagement, Praxis (3-16). UP of Colorado.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and psychotherapy research, 21(1), 37-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Hayfield, N. (2022). ‘A starting point for your journey, not a map’: Nikki Hayfield in conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about thematic analysis. Qualitative research in psychology, 19(2), 424-445.

Brooks-Gillies, M., & Moore, G. R. (2024). Negotiating relationships at the writing center: Removing roadblocks and building bridges. College Composition and Communication, 75(3), 558–584. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc2024753558

Calarco, J. M. (2020). A field guide to grad school: Uncovering the hidden curriculum. Princeton University Press.

Center for Excellence in Writing [@fiucew]. (2024, March 8). Happy International Women’s Day, Panthers! We’re thrilled to showcase Dr. Xuan Jiang’s contributions to the Center for Excellence in Writing [Photographs] Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C4Q-LruPAiD/?igsh=MTAxc2s5OGRxY3ZhZQ==

Cox, A., & Riedner, R. (2023). Persistence, coalition and power: Institutional citizenship and the feminist WPA. Peitho Journal, 25(2), 14-28.

Crowley-Watson, M. (2019). Social media, aggregators, analytics, and the writing center. Communication Center Journal, 5(1). Retrieved from https://janeway.uncpress.org/ccj/article/id/1050/

Delpit, L. (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. The New Press.

Efthymiou, A., & Fallert, R. (2022). Redefining collaboration through the extended work of writing center tutors: How undergraduate research expands opportunities for collaboration in higher education. College English, 84(6), 638–651. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce202231993

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical social research/Historische sozialforschung, 36(4), 273-290. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23032294

Fishman, J., Hovland, K., Leonhard, A., & Randhawa, S. (2022). Conducting consequential research: The access writing project. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Culture, and Composition, 22(1), 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-9385590

Fitzgerald, L. (2022). Writing centers: The best place for undergraduate research. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Culture, and

Composition, 22(1), 27-30. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-9385386

Florida International University – Digital Communications. (n.d.). Financial aid. FIU in Washington, D.C. https://washingtondc.fiu.edu/solutions/financial-aid/

Florida International University – Digital Communications. (n.d.). Generation initiatives at FIU. First-Generation Initiatives at FIU. https://firstgen.fiu.edu/index.html

Florida International University Student Life – US News Best Colleges. (n.d.). Florida International University Student Life. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/fiu-9635/student-life

Godbee, B., Bazan, J., Glise, M., Gonzalez, A., Quigley, K., & White, B. (2015). Stretching beyond the semester: Undergraduate research, ethnography of the university, and proposals for local change. PURM: Perspectives on Undergraduate Research and Mentoring, 3(2), 1-15. https://epublications.marquette.edu/english_fac/302/

Godbee, B., & Novotny, J. C. (2013). Asserting the right to belong: Feminist co-mentoring among graduate student women. Feminist Teacher, 23(3), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.5406/femteacher.23.3.0177

Haney, P. (2020). Collaborative practices to increase representation in the writing center. The Peer Review, 4(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-2/collaborative-practices-to-increase-representation-in-the-writing-center/

Herzl-Betz, R., & Virrueta, H. (2022). Perdiendo mi persona: Negotiating language and identity at the conference door. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Culture, and

Composition, 22(1), 169-172. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-9385624

Hughes, B., Gillespie, P., & Kail, H. (2010). What they take with them: Findings from the peer writing tutor alumni research project. The Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 12–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442343

Huot, B. (2002). Toward a new discourse of assessment for college writing classroom. College English, 65(2), 163-180. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce20021283

Huseby, A. K., & Thierauf, D. (2023). Cultivating a political learning ecology: An experimental cross-institutional course on climate change amid global precarity. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Culture, and Composition, 23(3), 435-460. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-10640022

Hutchinson, G., Jiang, X., & Avalos, M. (2023). Writing tutor alumni takeaways. The Writing Center Journal, 41(1), 69-86. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.2018

Inoue, A. B. (2016). Afterword: Narratives that determine writers and social justice writing center work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 94-99. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3dca9d9b-784e-4659-a950-f74d1af374b1/content

Jiang, X., Peña, J., & Li, F. (2022). Veteran–novice pairing for tutors’ professional development. Writing Center Journal, 40(2), 31-49. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1021

May, A. M. (2022). On networking the writing center: Social media usage and non-usage. Writing Center Journal, 40(2), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1022

May, A. M. (2023). Social media and the writing center: Five considerations. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 48(2), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.37514/wln-j.2023.48.2.03

Moore, J. L., Myers, A., & McConnell, H. (2022). Mentoring high-impact undergraduate research experiences. Pedagogy, 22(1), 17-21. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-9385352

Naydan, L. M. (2016). Generation 1.5 writing center practice: Problems with multilingualism and possibilities via hybridity. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 28-35. http://www.praxisuwc.com/naydan-132

North, S. M. (1994). Revisiting “The Idea of a Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal, 15(1), 7-19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442606

Robertson, D. L. (2022). Equifinality, equity, and intersectionality: Faculty issues in pursuit of performance metrics. Innovative Higher Education, 47(4), 683-709. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10755-022-09594-w

Roy, R., & Uekusa, S. (2022). Collaborative autoethnography: “Self-reflection” as a timely alternative research approach during the global pandemic. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(4), 383-392. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-06-2020-0054

Saturday, E. (2018). Tutors’ Column:” Reflecting (on) the research: Personal lessons from the IWCA collaborative”. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 43(3-4), 26-30. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A597253279/AONE?u=anon~e6d57daf&sid=googleScholar&xid=d0d376fb

Sawyer, R. D., & Norris, J. (2013). Duoethnography: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford UP.

Shapiro, S. (2022). Cultivating Critical Language Awareness in the writing classroom. Routledge.

Sohan, V., Peña, J., Jiang, X., & Rodriguez, G. (2025). Scenes from behind the scenes: Fostering reciprocal faculty-undergraduate coauthorships via feminist communities of practice. In L. Grobman & J. Greer (Eds.), Coauthoring with Undergraduates in Writing Studies: Revising Identities and Institutions (pp. 159-173). Utah State University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.36195817

Thonus, T. (2003). Serving generation 1.5 learners in the university writing center. TESOL Journal, 12(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1949-3533.2003.tb00115.x

Valdez, N., Carney, M., Yates‐Doerr, E., Saldaña‐Tejeda, A., Hardin, J., Garth, H., … & Dickinson, M. (2022). Duoethnography as transformative praxis: Conversations about nourishment and coercion in the COVID‐era academy. Feminist Anthropology, 3(1), 92-105.

Visse, M., & Niemeijer, A. (2016). Autoethnography as a praxis of care–the promises and pitfalls of autoethnography as a commitment to care. Qualitative Research Journal, 16(3), 301-312. https://doi.org/10.1002/fea2.12085

Wenger, C. I. (2014). Feminism, mindfulness and the small university WPA. WPA: Writing Program Administration-Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators, 37(2), 117-140.

Zauha, J. (2014). Peering into the writing center: Information literacy as collaborative conversation. Communications in Information Literacy, 8(1), 42741–42746. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2014.8.1.160

Appendix

Full Table of Student Testimonials