Bri Lafond, Boise State University

Carolyn Wisniewski, University of Illinois Urbana Champaign

Working from home can pose distinct challenges to writing center tutors. For example, Eleanor was a longtime tutor trained in nondirective, in-person practices. Despite this experience, she struggled to adjust to a fully remote setup due to limited technology access during the COVID-19 pandemic; later, she had to relearn her in-person strategies when she returned to the physical writing center. In contrast, Jeremiah had a well-supported home office with new technology sponsored by his department. Nevertheless, he struggled to balance his work-from-home setup with his home life: he, his wife, and child navigated overlapping Zoom calls for work and school in their two-bedroom home. Nyna began her tutoring career working from home, receiving training for synchronous video and asynchronous text-based tutoring sessions. When she began working at the physical writing center for the first time, she faced challenges adapting to a face-to-face tutoring context. Meanwhile, Maggie struggled tutoring remotely, sometimes resorting to talking with her tutees over the phone when she couldn’t make her own work-from-home technology work.

These consultants’ experiences are not well-represented in scholarship about online writing centers and online tutoring. Early writing center scholarship (Breuch, 2005; Hobson, 1998) conceptualized the creation of online writing centers (OWCs) as a straightforward process of transformation, recreating brick-and-mortar writing centers in virtual spaces. In this perspective, the OWC is a virtual recreation of the physical writing center, and the practices that work in the physical center should be simply adjusted to work virtually. In reality, the “space” of the OWC fluctuates depending on both tutors’ and tutees’ varied technological access, experience levels, and preferences. Though writing center studies scholars have begun to consider how OWC interfaces (Camarillo, 2022; Worm, 2018) and modes (Bell et al., 2022; Denton, 2017; Wisniewski et al., 2020) shape the practice of “online writing tutoring” (Prince et al., 2018), there remains a gap in understanding how online tutoring practices are shaped by the technologies, tools, and resources available to tutors.

In this article, we report on a qualitative study of tutors’ experiences with online tutoring both during and after COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. We found that tutors’ individual material conditions— technological access, resources, and work-from-home spaces—impacted their online tutoring practices, including interaction and collaboration as well as tutors’ affective, cognitive, and professional experiences of OWCs. While lockdown conditions were temporary, these experiences have had a lasting impact on both individual tutors’ and our writing center’s approaches to tutoring both online and in-person. Our findings trouble previous lore-based conceptions of OWCs as virtual spaces that reconstruct brick-and-mortar practices by offering empirical qualitative data on tutors’ practices of online writing tutoring (OWT). Based on our findings, we argue for a shift in emphasis from the online writing center as space to online writing tutoring as practice impacted by material conditions. This reframing affords the potential for tutors to consider how various writing and communications technologies shape the tutoring experience. Moreover, this shift offers the opportunity for writing center administrators to become more aware of how differences in material conditions and access to technology impact tutors’ experience and potentially reprioritize allocation of existing resources, including implementing more flexible tutor training to address these disparities. In doing so, our study contributes to the growing literature on modes of online tutoring (Barron et al., 2023; Neaderhiser &Wolfe, 2009; Wisniewski et al., 2020; Wolfe & Griffin, 2012) while also considering how differing material realities shape tutors’ experiences of online tutoring.

The Space of OWCs

In 1999, Elizabeth Boquet argued that writing center studies as a field has neglected the “politics of location”: a particularly glaring omission considering “the idea of the writing center metamorphoses from being one whose identity rests on method to one whose identity rests on site, and back again” (p. 465). Indeed, the physical space of the brick-and-mortar writing center is an oft-discussed topic in writing center studies: from cultivating a comfortable, “homey” atmosphere for tutees (Grimm, 1996; Grutsch McKinney, 2005) to designing optimal learning spaces (Zammarelli & Beebe, 2019). Others have critiqued those same spatial choices, particularly in relation to the accessibility of these institutional spaces for writers of color (Camarillo, 2019, 2020; Lockett, 2019) and disabled writers (Barron et al., 2023; Dembsey, 2020).

Beyond the brick-and-mortar writing center, many scholars have understood the OWC by employing spatial metaphors. Scholars have described various OWCs as “a home in cyberspace” (Miraglia & Norris, 2000), “an online country cottage” (Thomas et al., 2000), or “an elaborate HTML house” (Pegg, 1998). Indeed, Lee-Ann Kastman Breuch (2005), surveying OWCs’ web presence in the early 2000s, noted that many online sites attempt to “recreate aspects of writing centers as we know them in physical environments,” including “images of couches… to make the centers seem more homey” (p. 29). Embedded in these early, overly literal conceptions of OWCs is an apparent anxiety about the shift to virtual modality, best articulated by Eric Miraglia and Joel Norris’ (2000) contention that “overhyped” OWCs are a result of “cyber-anxious administrators” (p. 71). These anxieties emphasize that while writing center studies often focuses on practice rather than place, the field never strays very far from its “center” with an accompanying focus on space-based understandings of writing center work.

At the same time, the focus on space in relation to OWCs has rarely extended to considering the physical spaces and tools that tutors and tutees join the shared virtual OWC space from (Nadler, 2019). COVID-19 lockdowns—and the accompanying shift to work-from-home tutoring—highlighted how differing access to technology, resources, and spaces shape tutors’ virtual practices. Though many of these pandemic-era shifts were temporary, they were not entirely novel; emergency conditions have led to virtual shifts pre-pandemic (Nanima, 2019) and circumstances may arise in the future that lead to further transformations. Moreover, as the 2020–2021 Writing Centers Research Project Survey notes, nearly 95% of participating centers offer virtual services (Purdue Writing Lab, 2023), underscoring that a majority of tutors are logging on to provide OWC services, whether from their homes or from brick-and-mortar writing centers. The creation of the IWCA Special Interest Group for OWCs in 2015 (Prince et al., 2018) and the founding of the Online Writing Centers Association in 2020 further illustrate the growing interest in OWCs. Given the centrality of OWC sessions to contemporary writing centers, writing center practitioners need to better understand how tutors’ online tutoring practices are shaped by the various technologies, tools, and resources available to them.

Conceptual Models of Space

The spatial metaphors that writing center practitioners employ to describe OWCs guide how they understand these “spaces” to function. In fact, Breuch (2005) argues the established conceptual models for brick-and-mortar writing centers can unnecessarily limit how writing center tutors function in OWCs. She attributes these limitations to an inability to “apply what we know (our oral communication practices) as easily, quickly, or as well in the online environment” (p. 31). Specifically, Breuch argues that different writing centers create varying online presences around divergent conceptual models. For example, she notes that some OWCs only function as online advertising for brick-and-mortar centers, others offer online resources and worksheets, while others offer virtual tutoring services. Across these iterations, Breuch directly compares the OWC to its physical predecessor, focusing on recreating writing center dynamics in a virtual space.

However, the OWC’s physical predecessor is itself built upon divergent conceptual models. While writing center sessions arguably evolved out of the one-to-one writing conferences that instructors and students conduct around writing prepared for class (Harris, 1986), writing center sessions are not merely a “new and improved” version of the instructor conference. As writing center scholars have noted throughout the field’s history (Breuch, 2005; Grimm, 1996; Lunsford, 1991), practitioners understand writing center work through multiple and varied conceptual frameworks. For example, Andrea Lunsford (1991) compares three different writing center ideologies: “Storehouse Centers” where tutors provide writers with discrete, objective knowledge; “Garret Centers” where tutors assist writers in articulating their individual genius; and “Burkean Parlor Centers” where collaboration between tutors and writers is facilitated. Hobson (1998) argued early iterations of online writing centers served as virtual “filing cabinets and handbooks” (p. xvii) akin to Lunsford’s “Storehouse Centers,” while Breuch asserted early online writing centers struggled to foster the “Burkean Parlor Center” model within contemporary technological affordances. Other scholars have noted that integrating technology into brick-and-mortar writing center spaces impacts the work of writing center practitioners. For example, Amber Buck (2008) found in face-to-face tutoring sessions where the tutor and tutee looked at a text on a common screen, both tutor and tutee often became hyper-focused on the text itself and did not take advantage of the other affordances a computer might offer, such as using the internet to look up answers to questions that arose in the session. Thus, the history of the OWC is not a linear one in which the singular brick-and-mortar center is virtually remediated into the OWC space but instead a more complex intersection of writing center practices and emergent writing and communications technologies.

Online Writing Center Methods & Practices

While understanding the OWC as a virtual space remains a persistent framework (Brugman, 2019), some recent scholarship has shifted focus away from the space of the OWC and towards the practice of “online writing tutoring” (OWT) (Prince et al., 2018). For Prince et al. (2018), this distinction denotes a focus on multiple modes of tutoring practice (e.g., synchronous, asynchronous, hybrid) and away from the writing center as an online resource page (p. 10). This shift toward modality aligns with Boquet’s (1999) characterization of the field’s cyclical identity crisis: away from site and towards method. Indeed, ever-evolving digital tools and technologies have offered ever-evolving methods for tutors and tutees to connect, share, and discuss writing as well as enhance the accessibility of services for marginalized students (Barron et al., 2023; Camarillo, 2020; Dembsey, 2020).

Many early OWT methods were derived from online writing instruction principles (Hewett, 2005). Earlier OWT technologies were predominantly asynchronous, such as email tutoring (Honeycutt, 2001). Other early OWT technologies were synchronous but predominantly text-based, such as now-defunct MUDs (Multi-User Domains) and MOOs (Multi-User Domains, Object Oriented) (Lerner, 1998). Greater availability of multimedia OWT technologies has led to a proliferation of audiovisually-enhanced tutorials (Grutsch McKinney, 2010), including asynchronous screencasts (Bell et al., 2022) and synchronous multimodal sessions (Bhattarai et al., 2023). Considering these various modes, Anna Worm (2018) argues that foregrounding the discussion of technology within an OWC session can serve as its own pedagogical resource, allowing students to develop “meta-awareness about the implications of [various technologies] for collaborative writing work” (p. 43). Further, Megan Boeshart, Kim Fahle Peck, and Lisa Nicole Tyson (2023) argue that the proliferation of writing technologies and learning management systems that tutees must engage with necessitates that writing center tutors support students’ developing critical digital platform literacies so they can effectively navigate these systems.

With improved internet stability and access to video conferencing platforms (e.g., Zoom, Skype), OWT technologies are increasingly able to offer synchronous, face-to-face interactions that are seemingly equivalent to the kinds of face-to-face sessions that take place in brick-and-mortar writing centers. Nevertheless, as Lisa Eastmond Bell (2020) reminds us, the goal of OWT practices should not be mere replication of in-person tutoring dynamics, but rather learning-centered interactions that are both responsive to individual contexts and mindful of access and equity. Further, while OWT technologies are ever-evolving, both tutors and students’ access to these technologies may be limited (Camarillo, 2020). Increasingly, writing centers studies scholars are examining specific OWT practices across various modes (Barron et al., 2023; Neaderhiser & Wolfe, 2009; Wisniewski et al., 2020; Wolfe & Griffin, 2012) in order to better understand how modality impacts OWT practice from an empirical perspective (Driscoll & Powell, 2015). As Kathryn Denton (2017) notes, adherence to writing center “lore” often leads writing center practitioners to “dismiss ideas rather than explore them through research-based inquiry” (p. 177). Thus, rather than continually striving for OWT technologies that replicate the idealized in-person, face-to-face tutoring dynamic as much as possible, writing center studies scholars should consider what these different modes are able to offer both tutors and writers. Moreover, while scholarship increasingly focuses on OWT practices, the field should not entirely lose focus on the impact of space on shaping those practices. For example, Robby Nadler (2019) calls attention to the collapse between personal and professional identity that takes place when tutors connect with tutees in a work-from-home context and how that collapse can impact interactions between tutors and tutees. Our study aims both to better understand OWT practices and to learn more about how material conditions—particularly work-from-home conditions—shape those virtual practices.

Current Study

This IRB-approved study began as an examination of the material conditions of tutors’ home working environments during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and how those environments impacted tutors’ experiences; however, with the inclusion of follow-up interviews, the scope of the study expanded. In follow-up interviews, tutors compared their more recent in-person experiences to their work-from-home conditions. This research was guided by the following questions:

- What tools, technologies, resources, and spaces do tutors have access to in their work-from-home environments?

- What impact do these tools, technologies, resources, and spaces have on work-from-home tutoring sessions?

- What lasting impacts (if any) have work-from-home tutoring had on tutors’ practices?

Setting

This study took place at a flagship, doctoral-granting, Midwestern university. This writing center holds approximately 7,000 tutorial sessions annually, staffed by 30-40 undergraduate and graduate consultants from across the disciplines. The center began offering synchronous online sessions in 2017. With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, all tutoring moved online in March 2020 and the writing center remained entirely virtual until September 2021. In 2022, the writing center moved to a new physical location; today, it continues to offer in-person and virtual sessions as well as additional workshops and services. In-person sessions are held in the main writing center location in the campus library and in two satellite locations housed in academic buildings. Virtual sessions are offered in a variety of formats: 50-minute scheduled synchronous online sessions, on-demand synchronous online sessions of varying duration, and asynchronous written feedback sessions. These options are described on the center’s website alongside descriptions of additional writing center services (e.g., workshops), writing resources, and links to online scheduling. The center uses WCOnline, a popular schedule management and hosting platform, to schedule writing center sessions, host online tutoring sessions, and deliver asynchronous feedback documents to tutees. In addition to WCOnline, the center uses Zoom to host on-demand synchronous online sessions as well as virtual webinars. While these platforms—the center’s website, WCOnline, and Zoom—constitute the official online presence for the writing center, as noted in the findings below, tutors and tutees often employed additional technologies and/or used officially-sanctioned platforms in new ways.

Participants

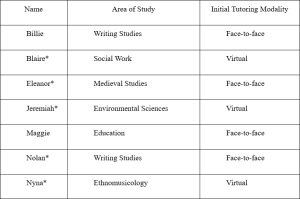

Participants were recruited by announcements made at biweekly staff meetings and through email. The seven participants were graduate students representing a variety of disciplines (see Table 1). All participants are referred to by pseudonyms. Four tutors began their writing center practice in a face-to-face modality before the pandemic while three first began tutoring virtually during lockdowns.

Table 1

Participant Area of Study and Initial Tutoring Modality

Note. * indicates follow-up interview participation

Data Collection and Analysis

All seven participants completed a 45-60-minute semi-scripted interview in May 2021 and five participated in a 45-60-minute follow-up semi-scripted interview between May and September 2022. Tutors were asked to provide basic demographic information, details about their work and school schedules, descriptions of their work-from-home spaces, and a list of the tools and technologies they used during sessions. The initial interviews elicited information about tutors’ perceptions of online learning as students and teachers, work-from-home conditions, goals for writing center sessions, types of services staffed, and recent experiences with synchronous and asynchronous tutoring sessions. The follow-up interviews included similar questions as well as questions gathering information about tutors’ recent experiences with in-person tutoring. During the follow-up interviews, participants were able to reflect on their experiences either returning to (Eleanor and Nolan) or working for the first time (Nyna and Jeremiah) in a brick-and-mortar location. One participant in the follow-up interviews (Blaire) remained fully online.

Interviews were conducted by the co-authors via Zoom; these interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed using Otter.ai, and then transcripts were checked against the original recordings. Data analysis was comparative and iterative (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The lead author read the interview transcripts, coding for the tools, technologies, resources, and spaces that tutors described in their various tutoring contexts. Some of these elements were part of the physical tutoring environment while others were part of the mediated, virtual space of the tutoring session. The lead author discussed these categories with the co-author to iteratively refine the categories, resulting in four categories that were defined and illustrated in a codebook.

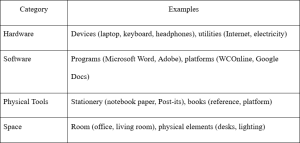

Ultimately, tutors’ responses were sorted into four categories: hardware, software, physical tools, and space (see Table 2). The term “hardware” refers to both literal electronic hardware (e.g., desktop computers, laptop computers, smartphones) as well as to hard-wired utilities (e.g., internet connection, electricity). “Software” refers to the programs (e.g., Microsoft Word, Adobe) and platforms (e.g., WCOnline, Zoom) that tutors made use of during tutoring sessions. “Physical tools” refers to non-electronic tools (e.g., pen, paper, books) used during the course of a tutoring session. “Space” refers to the space(s) that tutors work from (e.g., office, bedroom) and the physical elements that constitute those spaces (e.g., desks, seating, lighting).

Table 2

Code Categories

Results

In this section, we report on tutors’ material work-from-home conditions focusing on four areas: hardware, software, physical tools, and space. Across these categories, disparities in access to institutional and personal tools, technologies, resources, and spaces impacted tutors’ experiences. In response to these conditions, all participants developed ad hoc practices that served to center writing in tutorial interactions.

Hardware

Material resources varied widely among the tutors interviewed. These differences in resource access impacted both how tutors engaged with tutee’s writing and how they interacted with tutees during a given session. For example, one tutor—Jeremiah, situated in Environmental Science—was provided with several resources from his department to develop his work-from-home set-up: “I was able to take home a chair and two big monitors. My advisor got these expensive $100 webcams for us to bring home, so [my] setup is pretty good.” These resources, however, were the exception to the rule: no other tutor reported receiving tools from their department or the school, though nominally the university offered some technology—such as internet hotspots—for check-out early during lockdown.

Other tutors used their existing devices to work from home, adapted personal devices to use for work, or made use of loaned devices from family, roommates, or friends. For example, Eleanor used an old laptop borrowed from a friend: “I have been on a friend’s laptop for most of the school year because [my old computer] kept just literally crashing on me. It’s been kind of a strange way to interact because I am using someone else’s computer, and I was still signed on as [my friend’s account] and that’s not who I am… And the ‘O’ and the ‘U’ keys don’t work, so I have to have this guy [gestures to a peripheral keyboard].” Blaire used her own laptop plugged into her partner’s dual monitors so that she had three screens to virtually “spread out” on: “I [use] the monitors to help look at the documents or to be able to see [the tutee’s] face better on video or to take my notes and write up the client report form.”

The utility that had the most impact on tutors’ working conditions was internet connectivity. Many tutors reported unstable internet connections, particularly when they shared an internet connection with roommates or other family members. Nyna noted that when she experienced internet connectivity problems during a session, she would text her husband the word “Internet,” and he would troubleshoot issues at the modem located in another room. As a result of internet issues, some tutors occasionally had to improvise solutions to continue online sessions. Billie, for example, reported using her phone “to provide data” for her laptop to stay connected; however, she was limited in accessing other online resources while connecting to the internet in this way. Maggie, an older, nontraditional student, reported needing to make direct phone calls to some tutees: “When I was consulting, there were a couple of times when it worked best to be on the phone with somebody and looking at a Google Doc. I did that with a couple of people [when] for whatever reason, it kind of failed.”

Ultimately, these differences in access to devices and utilities impacted consultants’ ability to provide effective writing center sessions, as many needed to improvise and troubleshoot on the fly, leading to markedly different OWC experiences for tutors and writers.

Software

Programs and platforms were often chosen in consultation with individual tutees to preserve writer agency and to encourage collaboration. While the writing center employs WCOnline as both a scheduling tool and a means to video conference with tutees, many tutors and tutees preferred using alternative platforms or using WCOnline as part of a multi-platform tutoring session. For example, Nyna noted that “many people” she worked with regularly—“especially older writers or writers working on bigger projects”—would include both a Zoom link and a Google Docs link in their WCOnline appointment form. Though Nyna generally preferred this set-up—the combined use of Zoom and Google Docs—she would not “initiate” a shift in platform unless she was experiencing a “problem” with WCOnline. In general, she would “walk [tutees] through their different [platform] options,” but she would allow the writer to choose which platform(s) they wanted to use for a session. Nyna also reported using different platforms for specific purposes: “We sort of work our way toward having both Google [Docs] open with the document and WCOnline as sort of a playground space. That’s been really helpful as well.” In this instance, while WCOnline could host both the video and the document itself, Nyna and the student used WCOnline as a place to take notes separate from the document on Google Docs. Eleanor similarly noted that she preferred using Google Docs because it is “an interface where I can highlight or underline what we’re talking about… I think without that, it’s easy to get lost.”

While greater familiarity with platforms like Zoom could mean the tutor would need to dedicate less time introducing WCOnline’s interface to a student, some of these outside platforms’ other features could lead to awkward interactions. Eleanor described one session during which the student gave her remote control: a Zoom feature that allows one user to take control of another user’s screen. Eleanor expressed discomfort with having control of the student’s screen: “I really don’t like when I do get remote access over people’s computers because it feels very invasive to me. I feel like I’m invading [their space].” At the same time, she also felt uncomfortable directing students too much in controlling their own shared screen during a session: “That’s actually one reason why I don’t like [using] Zoom with a shared screen… I don’t really feel comfortable that I have to boss [tutees] around and be like, ‘Now you scroll up [on your document]’ or something. I just don’t like that.”

Zoom also afforded the ability for tutors and tutees to look at more specialized programs and formats than might not have been possible in other modalities. For example, Billie described working with a graduate student on revisions for an article manuscript. The student used Zoom’s screenshare function to share his own computer screen where he used Overleaf, an online program that allows users to revise LaTeX-formatted documents (LaTeX is a typesetting system that formats text for publication) to produce “a clear, clean copy of the PDF.” Zoom’s screenshare function allowed the student to share the document in a form that Billie otherwise could not access since she did not have the Overleaf program. Billie also used another Zoom functionality in these sessions to offer feedback by “read[ing] on his screen and [making] suggestions using the annotation function.” Zoom’s annotation tool allows users to add text or drawings to the shared screen; in this instance, the student was able to see Billie’s suggestions and then make changes himself using the Overleaf interface.

In addition to Zoom, another platform frequently used during tutoring sessions was Google Docs: all seven tutors reported using Google Docs with tutees, typically in conjunction with other synchronous technology (i.e., WCOnline, Zoom, direct phone call). While WCOnline offers a virtual whiteboard with real-time collaborative writing capabilities, many tutors preferred—and noted that their tutees preferred—using Google Docs during sessions to look at writing. Tutors suggested that greater familiarity with Google Docs and WCOnline’s tendency to restructure formatted text were the main advantages to using Google Docs rather than WCOnline’s whiteboard. Additionally, as Nyna noted, Google Docs allows users to “see the other person’s cursor and where they’re highlighting” which is “so helpful” during virtual sessions; Google Docs’ commenting feature allows tutors to comment on specific sections of a given text in ways that WCOnline’s separate whiteboard and chat function do not.

Finally, some tutors employed additional software for their personal note-taking use during sessions. For example, Blaire developed her own system of note-taking using Microsoft Word: “If I have multiple sessions in a row and I know that they’re going to be longer, I just have one Word Doc and [write] separate pages for each person that I’m working with.” She then went back and edited those notes into a narrative, adding links to various resources (e.g., pertinent Purdue OWL pages, campus resources like the Career Center), then copied and pasted the revised narrative into the client report form on WCOnline to send to the tutee. Jeremiah and Maggie also mentioned employing Microsoft Word during sessions in a similar way. At the start of a session, Jeremiah would draft a session agenda in collaboration with the tutee in Microsoft Word: “I usually type down… a couple bullet points, and then kind of peek over at it again [during the session] making sure we’re staying on course.” Maggie took notes in Microsoft Word during sessions then saved those notes in a work folder labeled “with the date and the name of the person” to refer back to in case the tutee made another appointment.

Participants reported navigating a range of programs and platforms, including WCOnline, Zoom, Google Docs, and Microsoft Word. Tutors and writers found varying affordances and constraints across these platforms, with software impacting communication, text-sharing, revision, and notetaking. Through exploration and collaboration with writers, consultants found by trial-and-error the programs and platforms that would best facilitate their tutoring sessions without pushing past boundaries of authorship and agency.

Physical Tools

While tutoring sessions took place in a virtual space and the materials that both tutors and tutees interacted with were virtually mediated, tutors still made use of “old-fashioned” technologies beyond the screen. Nolan, for example, noted that he would keep his “journal and notebook” ready on his desk during sessions. Both Maggie and Eleanor mentioned integrating books into their work-from-home set-ups not for their content but as props; Eleanor noted, “I have [my friend’s] little MacBook on several books to make it kind of higher” and thus at a more comfortable angle to work with. Other tutors employed physical tools to support their individual thought processes during tutoring sessions. For example, Eleanor reported keeping “a pen or pencil” and “a stack of index cards” or Post-its near her computer during sessions so that she could take notes on writers’ “concerns” or “goals.” Pre-pandemic, Eleanor would take similar notes; “I worked a lot with [a mentor tutor] who works with yellow legal pads, and I think that kind of stuck with me.” Eleanor asserted that the notes she typically took near the start of a session—in either the in-person or the virtual context—tended to serve as “a planning meeting” or agenda-setting in order to guide the session. As a session progressed, though, the notes would become “something that [the tutee] can take home with them.” In the work-from-home context, these notes wouldn’t be literally taken home by writers, but Eleanor continued the practice as a means of supporting her own cognitive process during sessions.

Interestingly, in the return to a physical writing center location, Eleanor’s practices in relation to the use of physical tools once again shifted. Post-pandemic, the writing center moved to a new location, so not all tutors were familiar with where various tools and resources were located. In the follow-up interview, Eleanor noted that she hadn’t yet found “pens and paper and stuff” in the new space and that she felt “kind of naked” without these tools. She further noted that not having physical tools made her feel as if she was “trying to keep everything in [her] head,” thus slowing down her thinking in sessions. Eleanor admitted that she hadn’t reached out to the director to ask about these tools, though she knew that the issue “would be immediately fixed” when she did bring it up. She hadn’t taken the steps to remedy the issue, though, as she tended to now just go into the center, tutor her sessions, then leave.

Whether working in-person or online, many tutors still used physical tools to support their cognition, facilitate agenda setting, and modify their work environment. Such tool use suggests that OWCs are never fully online, and tutors are always navigating multiply-mediated environments. As such, the various material conditions that tutors inhabit always already impact the work they are able to perform.

Space

The spaces tutors worked from affected both their OWT practices and shaped their interactions with tutees. Tutors discussed how both their work-from-home spaces and the brick-and-mortar writing center impacted their approaches to OWT.

Work-from-Home Spaces

Work-from-home spaces varied widely: tutors worked from private office desks, kitchen tables, couches, and beds. Moreover, these spaces were further shaped by the people and pets who occupied them. Accordingly, these disparate spaces had varied impacts on the tutors, their practices, and their construction of identity in spaces that potentially blurred professional and personal boundaries.

The presence of other people in the home impacted several tutors: tutors who lived with roommates or family members and who did not have a dedicated, private office space often had to accommodate the needs of their co-habitants. For example, Nolan’s limited space—a two-bedroom apartment shared with a roommate—meant that he had to “work exclusively in my bedroom, but I don’t like to… My roommate has sort of monopolized the living room.” He would take care to angle the camera so as not to show his bed, noting that he wanted to present a “semi-professional identity on my camera.” In this way, Nolan used the hardware available to him to shape how his personal space was represented to tutees. Blaire’s working conditions were similarly impacted by the presence of her partner: “I’m in a one-bedroom apartment. Right now, I’m in the bedroom because my fiancé’s home. Usually during the day [when] he’s at work, I will be at a desk [with] two monitors set up in addition to my laptop. Very nice setup… For my 7pm to 10pm appointments, I just use my laptop [in the bedroom].” This shift in working conditions marked a number of changes: in ease of access to various electronic resources, as Blaire no longer had dual monitors on which to virtually “spread out;” in physical comfort, as she no longer had a backed chair on which to sit; and in personal comfort, as she now had to meet with writers from a much more personal space.

The intermingling of personal and professional selves was also a concern for Jeremiah. Early in the lockdown, Jeremiah worked from a desk set up in the bedroom he shared with his wife. He noted that between himself, his wife, and their daughter, “a third” of their two-bedroom apartment was devoted to “workstyle for Zoom.” While he possessed a better tech set-up than many other tutors (as noted in the “Hardware” section), the lack of private space meant each family member’s work and/or school activities ended up impacting the others. During the follow-up interview, Jeremiah mentioned his family had moved to a larger place: “Now there’s three bedrooms, so it’s a lot better. I don’t have to kick anybody out or close the door. It’s a much better, more comfortable home situation.” While the move meant that he had a dedicated workspace to tutor from, Jeremiah did still have to share that tutoring space with his side business and its employees: frogs. Jeremiah began running a frog breeding business, meaning his dedicated workspace was lined with terrariums featuring occasionally croaking frogs: “It’s more awkward than I thought it would be because it seems so normal… It can be a nice, like, intro to online sessions because they have something to talk about… [but] also it can be kind of weird… if it was just a plain white background… maybe it would be easier.” The frogs also provided occasional distractions: “I’ve been [working] afternoons, and [the frogs] do [make a lot of noise] in the morning after we’ve misted the terrariums. Usually, it would get pretty loud here. But afternoons it’s not too bad.” While the visible and aural presence of the frogs could occasionally disrupt tutoring sessions, their presence mainly served as a means of developing a rapport with tutees.

Jeremiah was not the only tutor to mention the impact of animal co-workers. For example, Billie enjoyed having her small dog with her when she worked from home because of his companionship, but she had to keep the blinds down in her communal workspace because the dog would “start barking if he sees anything else out the window.” Nyna’s young cat would occasionally act out during tutoring sessions, necessitating that she “step out for a second and just make sure that everything was okay.” She explained that she didn’t feel she could let the cat into her office during work hours because the few times she had let her in, she would sit on the desk next to Nyna, meow loudly, and swat at the screen.

Brick-and-Mortar Spaces

In follow-up interviews, participants discussed how their virtual practices were remediated into face-to-face sessions, some for the first time. The space of the physical writing center impacted tutors’ experiences across multiple dimensions, including social dynamics, different access to hardware and physical tools, navigating multiple tutoring modalities across one work shift, and general approaches to tutoring.

Nyna—who had previously only ever tutored online—emphasized the shift in interpersonal dynamics both among tutors and between tutors and tutees in the physical writing center space. For example, she mentioned that working in the communal space of the writing center felt strange because of the “lack of privacy” afforded to students writing about more personal topics: “I do have some regular [tutees]… we had met so regularly for the two years that I was a consultant [online] that they had disclosed some pretty personal information. I personally cannot imagine doing those sessions in a space that has other people in it. That sounds really weird, but I can’t imagine having gotten to that place and having actually given these writers the support that they needed to write about these very sensitive things in a public space.” She also observed that working from the physical writing center is “nice because people can talk to each other between sessions, but it’s also not nice that [tutors] can’t actually mentally leave work for that long” like they could working from home. Essentially, the social dynamic of the brick-and-mortar writing center evolved in response to tutors’ enculturation into OWT for an extended period of time.

In the local context, the main location of the writing center moved to a new building during the campus’s return from the pandemic. In the previous writing center location, tutors and tutees often worked together in semi-private cubicles; Eleanor realized that when she began working in the new space that she “gravitated toward the first cubby that I saw, so I think I’m trying to recreate the old space in some way.” In contrast, most folks in the new location tend to spread out more, often resulting in tutors and tutees looking at texts on their own devices rather than on a shared screen or printed draft. Eleanor described a group tutoring session that took place in the center between herself, a student-tutor, and a tutee in which she and the tutee worked off “two separate copies” of a draft while the student-tutor accessed the draft from her laptop. Eleanor noted that she felt “less prepared because I had just not brought my laptop.” She also explained that while the writing center has a couple of desktop computers to work from, she often finds these devices less usable than her own since she doesn’t have all her passwords memorized to access useful platforms (e.g., Google Docs).

Continuing concerns about COVID-19 have also led to lasting changes in social dynamics within the writing center. For example, there can be an additional level of negotiation involved with in-person tutoring with regard to choices about masking. Nyna explained to tutees that she would keep her mask on and that sometimes led to “awkwardness” with the tutee asking if they needed to “distance” themselves from her during a session. Eleanor noted that tutees tended to be “pretty respectful” of her own decision to continue masking: usually, “if they see the mask, they put one on” to work with her.

While many of the tutors now regularly work in the physical writing center location, many tutees continue to book online appointments, meaning that virtual tutoring practices have continued despite the individual tutor’s location within the brick-and-mortar center. In fact, tutees select whether they want to meet with a tutor in-person or online, so while the tutor works in the center, they might go from an in-person session to an online session and back again over the course of a single shift. Eleanor noted “going from doing this [online session] to meeting with someone at a table is very interesting, that kind of switch. I don’t know that I have a specific thing to name that feeling, but it’s very peculiar to move from [online] to go meet someone at a table.” Similarly, Nyna said she was “interested to see what that constant shift in modality does not even just for the logistics of our lives but how we think about things and how we learn.”

Discussion

While early conceptions of OWCs focused on re-creating the experience of face-to-face sessions in virtual spaces (Breuch, 2005), there remains a gap in understanding how online tutoring practices are shaped by the various technologies, tools, resources, and spaces available to tutors. This qualitative study of seven graduate writing tutors found that variable material resources impacted tutors’ access and interactions: software was chosen in consultation with tutees to preserve collaboration and writer agency, physical tools supported tutors’ cognition and session structure, and spaces shaped tutorial practices and tutors’ negotiation of personal and professional identities. By highlighting how consultants centered writing during tutoring sessions, our study contributes to the recent turn in writing center scholarship toward OWT practices (Prince et al., 2018). However, as evidenced by the disparate experiences of the research participants, the role of space—specifically, the spaces beyond the screen that tutors (and tutees) inhabit—cannot be entirely discounted.

The focus on space in OWC scholarship (Breuch, 2005; Hobson, 1998) has rarely extended to consider tutors’ access to hardware, software, physical tools, and spaces. Our participants’ experiences underscore how variable access to resources accordingly affected tutorial practices. For example, Eleanor’s typical tutoring practice focused on nondirective approaches, such as taking her own session notes on a separate sheet of paper and having the student control their own document. In virtual tutoring sessions, platforms like Zoom challenged this hands-off approach since students could enable Eleanor to remotely control their computers without asking her first. She had to learn how to manage these tutees’ expectations in the virtual environment in new ways than she had in the physical center.

Other differences in tutor experience and practice resulted from differing institutional resources and personal material constraints; for example, while Jeremiah received ample technological support from his home department, his individual living situation constrained his at-home working conditions. In other instances, differences resulted from tutors collaboratively negotiating with their tutees the platforms and tools utilized during a given session. As one example, Billie working with her tutee to employ Zoom, Overleaf, and LaTeX during a session allowed them to utilize technological affordances that WCOnline does not possess. Some differences resulted from directly translating existing in-person tutoring practices to virtual ones. For example, Eleanor continued to take notes with pen and paper even though the practicality of that method shifted in the context of virtual tutoring. While tutees would no longer receive the handwritten notes at the end of the session, Eleanor still used them as a personal resource and cognitive aid while tutoring. Finally, differences manifested from the varied spaces inhabited by these consultants as well as their human and animal companions; constructing and controlling their workspaces necessitated consultants’ negotiation of personal and professional identities (Nadler, 2019). For instance, Nolan took care to position his camera so as not to reveal that he was working from his bedroom in order to appear “semi-professional” to tutees.

Our study finds that some tutors do remediate their existing in-person tutoring practices for the online environment, such as Eleanor’s use of handwritten notes during sessions. This use of existing practices in new interfaces aligns with earlier writing center literature regarding the development of OWCs (Breuch, 2005); specifically, that the OWC should recreate the physical center’s non-directive discursive practices (Lunsford, 1991). However, our study also demonstrates that this transfer of practices is not a unidirectional phenomenon: a reverse trajectory occurs as well. Some tutors who participated in the study had never tutored face-to-face before the pandemic; their practices were what we might call “born digital.” These tutors weren’t directly remediating their experiences from face-to-face practices but building their own practices online. For example, Blaire’s system of note-taking in Word grew organically from her day-to-day OWT practice as opposed to being handed down to her during tutor training, like Eleanor’s note-taking practices learned from working with a mentor-tutor in the physical center. As a result of the varied experiences that tutors brought to virtual tutoring, what any given tutoring session looked like and how it functioned shifted widely. As such, we might argue that our institution does not have one online writing center but instead offers several means of connecting writers with tutors to discuss their work: from one online writing center space to practices of centering writing online.

To center writing online means to take advantage of technological affordances to develop a conversation around writing that isn’t limited to one approved virtual “space.” For writing center practitioners, our business is “centering writing” in conversations about the products and processes of writing. Whether we have these writing-centered conversations in the physical center or across multiple virtual platforms simultaneously, the idea of centering highlights the practices that tutors engage in across the varied spaces they occupy. Integrating this writing-centered perspective has implications for how tutors think about their pedagogical approaches, such as Nyna considering how privacy (or lack thereof) might impact the work she was able to do with tutees in sessions. Tutors often embraced the possibilities afforded by working beyond the standard platforms, but that same flexibility also led to new practical challenges, such as Eleanor’s discomfort with tutees using technology to challenge her nondirective approach.

These challenges highlight the need to address flexible practices of centering writing in staff training. As one example of what centering writing in staff training looks like: our center’s virtual staff meetings during lockdowns often focused on ways to use and incorporate different technologies into sessions, such as how to change share settings on collaborative Google Docs or how to use a smartphone as a makeshift document camera to capture handwriting. These strategies looked beyond the WCOnline platform to afford tutors new ways to discuss writing with students in virtual sessions. In particular, these techniques were intended to support tutors to respond in the moment to tutees’ specific needs and their own technological limitations. While our center focused on empowering tutors with new technological possibilities during lockdowns, what our results demonstrate is the need to further address the implications of embracing new technologies in OWT, including how to establish professional boundaries with and adapt pedagogical practices to tutees across varied platforms.

Our study further contributes to the scholarly conversation around the efficacy of various OWT practices and technologies (Bell, 2020; Denton, 2017). We argue that rather than striving for OWT technologies that replicate idealized face-to-face tutoring dynamics (Breuch, 2005), writing center studies scholars should consider what different modes are able to offer tutors and writers. This study illustrates how tutors developed learning-centered interactions responsive to their individual context (Bell, 2020). Our study therefore offers implications for tutor training that emphasizes this focus on centering writing, both in taking advantage of new technologies and in learning how to set new boundaries in virtual spaces. Training that focuses on “centering” explicitly addresses the material conditions in which tutoring takes place and explores how shifts in those material conditions shape tutors’ practices. While OWT has the potential to greatly increase accessibility for marginalized students (Barron et al., 2023; Dembsey, 2020), writing center practitioners need to remember that tutors’ access to both OWT technologies and space can be incredibly varied. These differences can potentially marginalize tutors who struggle to work with inadequate devices or from shared living spaces. By focusing on “centering,” administrators can better accommodate both students and tutors. For example, if a tutor voices concerns about meeting with students synchronously using their own technology, an administrator might work with that tutor to either secure a more reliable device or schedule the tutor to work on asynchronous feedback during a work-from-home shift.

Further, focusing on “centering” in tutor training opens up opportunities for new pedagogical approaches. For example, tutors can learn to integrate more collaborative technology choices and metadiscussion about those choices in sessions. As Worm (2018) notes, specifically discussing interfaces with tutees during sessions provides instructional value beyond the tutorial, such as demonstrating how the tutee might employ similar collaborative writing technologies to work with other students on a group project. Indeed, facilitating discussions with tutees about their various options for centering writing might be part of a larger pedagogical approach, helping tutees to develop digital platform literacies (Boeshart et al., 2023).

Paying closer attention to how technologies shape tutoring sessions can also help tutors to better support tutees’ specific needs. For example, if a tutee wants to discuss particularly sensitive work, tutors can review their different session options (e.g., in-person, synchronous online, asynchronous written feedback) in order to select a session mode that the tutee will be most comfortable with. Emphasizing practices of centering writing rather than adhering to mandated OWC tools affords tutors and tutees flexibility: the flexibility to integrate the platforms they are comfortable with into a session as well as the flexibility to utilize proprietary technologies that may not be licensed by the writing center.

The varied resources available to tutors constitute their ability to center writing online and can subsequently constrain their choices. These choices (or lack thereof) have implications for how administrators approach OWC design and training. Tutors would benefit from training that directly addresses how varied technological access impacts OWT practices; for example, how they might negotiate personal and professional boundaries with tutees when they work from home (Nadler, 2019). Additionally, providing technology for tutors to take home (e.g., Internet hot spots, laptops, webcams, headsets) would be one way to increase tutor access to a variety of pedagogical options. Further, given the enhanced infrastructure that most brick-and-mortar writing centers have built-in, making better spaces within the physical writing center for tutors to offer virtual tutoring services is an important step. For example, in follow-up interviews, all the tutors who returned to in-person tutoring noted that the echo of the new tutoring room made it difficult to hear tutees in online sessions; in response, the writing center director was able to obtain sound-dampening panels for the room to improve tutor (and tutee) experience. This study demonstrates that while not all tutors employ the same tools and resources, all tutors (and tutees) would benefit from having the choice to use a variety of tools and resources rather than being forced to choose from what may be available to them. Indeed, we are not arguing that the pendulum should swing fully back to “method” and away from “site” (Boquet, 1999); rather, we are drawing attention to how the different material realities that tutors embody beyond the screen shape OWT practices.

Conclusion

While this study considers tutors’ OWT practices, there are some limitations in our approach and much more work to be done. Our study only considered the experiences of a relatively small number of graduate writing consultants: no undergraduate tutors volunteered to participate, and our site does not employ professional tutors. Though we interviewed our participants both during and after COVID-19 lockdown conditions were in place, the long-term impacts on tutoring practices are yet to be seen. For example, as Nyna noted, we have not yet studied the implications of “constant shifts in modality” on tutors. Additionally, our study is situated within our local context; it remains to be seen whether ad hoc practices are common across institutions, particularly different types of institutions.

Nevertheless, this article joins recent scholarship in encouraging a reconceptualization of OWCs, re-centering writing center practitioners’ focus away from the center-as-space and towards centering-as-practice (Prince et al., 2018). This study also joins the turn away from theoretical and lore-based scholarship and toward empirical research (Denton, 2017). Future studies should continue to explore the specific practices that tutors employ across the varied spaces in which they center writing. By continuing to “question our assumptions about online tutoring” (Wisniewski et al., 2020), we are able to better understand both what online writing tutors do and subsequently, what tutors need from writing center administrators to do that work.

References

Barron, K. L., Warrender-Hill, K., Wallis Buckner, S., & Ready, P. Z. (2023). Expanding writing center space-time: Tutoring, modality, access, and equity. The Peer Review, 7(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-7-1-featured-issue-reinvestigate-the-commonplaces-in-writing-centers/expanding-writing-center-space-time-tutoring-modality-access-and-equity/

Bell, L. E. (2020, September 4). Rethinking what to preserve as writing centers move online. Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders. https://wlnconnect.org/2020/07/20/rethinking-what-to-preserve-as-writing-centers-move-online/

Bell, L. E., Brantley, A., & Van Vleet, M. (2022). Why writers choose asynchronous online tutoring: Issues of access and inclusion. WLN: Writing Lab Newsletter, 46(5-6), 3-10. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v46n5/belletal.pdf

Bhattarai, P., Colton, A., Kim, E., Manning, A., Schonberg, E., & Zhou, X. (2023). Reading the online writing center: The affordances and constraints of WCOnline. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 20(2). https://www.praxisuwc.com/202-bhattarai-et-al

Boeshart, M., Peck, K.F., & Tyson, L.N. (2023, October 11 – 14). Platform literacy as essential for tutor development in the increasingly multimodal writing center [Conference presentation]. IWCA 2023 Conference, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Boquet, E. (1999). ‘Our little secret’: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463-482. http://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/english-facultypubs/2

Breuch, L. K. (2005). The idea(s) of an online writing center: In search of a conceptual model. Writing Center Journal, 25(2), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1527

Brugman, D. (2019). Brave and safe spaces as welcoming in online tutoring. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/brave-and-safe-spaces-as-welcoming-in-online-tutoring/

Buck, A. (2008). The invisible interface: MS Word in the writing center. Computers and Composition, 25, 396-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2008.05.003

Camarillo, E. C. (2019). Burn the house down: Deconstructing the writing center as cozy home. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/burn-the-house-down-deconstructing-the-writing-center-as-cozy-home/

Camarillo, E. (2020, April 30). Cultivating antiracism in asynchronous sessions. South Central Writing Centers Association Blog. https://writingcenter08.wixsite.com/scwcaconference/post/cultivating-antiracism-in-asynchronous-sessions

Camarillo, E. (2022). A parliament of OWLS: Incorporating user experience to cultivate online writing labs. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 19(1). https://www.praxisuwc.com/191-camarillo

Dembsey, J. M. (2020). Naming ableism in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 18(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/181-dembsey

Denton, K. (2017). Beyond the lore: A case for asynchronous online tutoring research. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 175-203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44594855

Driscoll, D. L., & Powell, R. (2015). Conducting and composing RAD research in the writing center: A guide for new authors. The Peer Review, 0. https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-0/conducting-and-composing-rad-research-in-the-writing-center-a-guide-for-new-authors/

Grimm, N. M. (1996). Rearticulating the work of the writing center. College Composition and Communication, 47(4), 523-548. https://www.jstor.org/stable/358600

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2005). Leaving home sweet home: Towards critical readings of writing center spaces. Writing Center Journal, 25(2), 6-20. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1526

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2010). Geek in the center: Audio-video-textual conferencing (AVT) options. Writing Lab Newsletter, 34(9-10), 11-13. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v34/34.9.pdf

Harris, M. (1986). Teaching one-to-one: The writing conference. NCTE.

Hewett, B. L. (2005). Synchronous online conference-based instruction: A study of whiteboard interactions and student writing. Computers and Composition, 23(1), 4-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2005.12.004

Hobson, E. (Ed.). (1998). Wiring the writing center. Utah State University Press.

Honeycutt, L. (2001). Comparing e-mail and synchronous conferencing in online peer response. Written Communication, 18(1), 26-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088301018001002

Lerner, N. (1998). Drill pads, teaching machines, and programmed texts: Origins of instructional technology in writing centers. In E. Hobson (Ed.), Wiring the writing center (pp. 119-136). Utah State University Press.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: A critical examination of race, place and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2), 20-33. https://doi.org/10.26153/tsw/2679

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3-10. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441887

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Miraglia, E., & Norris, J. (2000). Cyberspace and sofas: Dialogic spaces and the making of an online writing lab. In J. A. Inman & D. N. Sewell (Eds.), Taking flight with OWLs: Examining electronic writing center work (pp. 71-84). Routledge.

Nadler, R. (2019). Sexual harassment, dirty underwear, and coffee bar hipsters: Welcome to the virtual writing center. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/sexual-harassment-dirty-underwear-and-coffee-bar-hipsters-welcome-to-the-virtual-writing-center/

Nanima, R. D. (2019). From physical to online spaces in the age of the #FeesMustFall protests: A critical interpretative synthesis of writing centres in emergency situations. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, 57, 99-116. https://doi.org/10.5842/57-0-812

Neaderhiser, S., & Wolfe, J. (2009). Between technological endorsement and resistance: The state of online writing centers. Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 49-77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442314

Pegg, B. (1998). UnfURLed: 20 writing center sites to visit on the information highway. In E. Hobson (Ed.), Wiring the writing center (pp. 197-215). Utah State University Press.

Prince, S., Willard, R., Zamarripa, E., & Sharkey-Smith, M. (2018). Peripheral (re)visions: Moving online writing centers from margin to center. WLN: Writing Lab Newsletter, 42(5-6), 3-10. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v42n5/princeetal.pdf

Purdue Writing Lab. (2023, July). 2020-21 writing center research project. Purdue OWL. https://tableau.it.purdue.edu/t/public/views/WCRP2020/2020-21WCRPResults

Thomas, S., Hara, M., & DeVoss, D. (2000). Writing in the electronic realm: Incorporating a new medium into the work of the writing center. In J. A. Inman & D. N. Sewell (Eds.), Taking flight with OWLs: Examining electronic writing center work (pp. 59-64). Routledge.

Wisniewski, C., Carvajal Regidor, M., Chason, L., Groundwater, E., Kranek, A., Mayne, D., & Middleton, L. (2020). Questioning assumptions about online tutoring: A mixed-method study of face-to-face and synchronous online writing center tutorials. Writing Center Journal, 38(1-2), 261-296. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/27031270

Wolfe, J., & Griffin, J. A. (2012). Comparing technologies for online writing conferences: Effects of medium on conversation. Writing Center Journal, 32(2), 60-92. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43442393

Worm, A. (2018). A new window: Transparent immediacy and the online writing center. In C. E. Ball et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of the Computers and Writing Annual Conference, 2016 & 2017 (Vol. 1, pp. 41-47). The WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/proceedings/cw2016/worm.pdf

Zammarelli, M., & Beebe, J. (2019). A physical approach to the writing center: Spatial analysis and interface design. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/a-physical-approach-to-the-writing-center-spatial-analysis-and-interface-design/