Caitie Leibman

The Peer Review, Volume 1, Issue 2, Fall 2017

Following the 2016 presidential election, the International Writing Centers Association crafted a post on its website to reassert “its long commitment to civil discourse, inclusive language, and collaborative practice.” On my own university campus, I witnessed no similar affirmations: diversity and inclusion organizations and the administration remained publicly silent. I sensed, however, that many students and community members were struggling to process the results.

For instance, behind closed doors, a Muslim student told me they were feeling isolated: when they tried to voice their fear of potential violence, hatred, and policy changes that would disproportionately affect them and their family, their (white) Christian friends continuously dismissed their feelings.

I opened the floor for conversation in a writing class two days after the election, and an LGBTQ student emailed to thank me for being their only teacher to even mention the results that week.

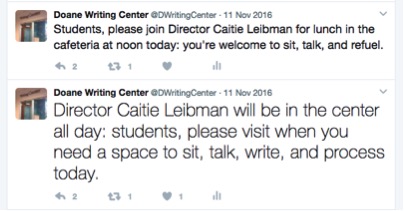

As a writing center director, I reacted to these experiences by doing what I could: I tried to communicate that the center was an available space—even without knowing what exactly I meant by that—and that I was available (Figure 1).

With available time and an office housed inside the center, I was able to use Twitter on the Friday after the election to make these gestures to students.

Despite these invitations, I didn’t feel I was “doing enough” for my students in this moment, as a teacher or director. By the end of election week, I was imagining something bigger. I decided to leverage our Writing Center’s existing public events series to offer a new type of space for students—a visible, inclusive presence, that would hopefully signal to marginalized members in our community that the Writing Center saw them, heard them, and was them. I organized an event called “Speaking Truth to Power,” promoted as part of our Write Out Loud (WOL) reading series; the series celebrates original writing across campus by inviting writers to reserve a 10-minute slot to read or perform their writing at one of our four annual, themed evenings.

The idea thrilled me, but I was scared. I had already felt anxiety just trying to compose tweets that week, and now I was going to create a public event centering on what was a kairotic moment for our campus and our country? I witnessed our campus environment become clouded by dismissal, silenced, and lack engagement.

Choosing to engage, however, posed risks. I was manufacturing a loaded opportunity for myself and the other speakers: each of us would be vulnerable, sharing our truths, concerns, and pleas on a literal stage, to whatever audience chose to attend. While many educators employ the concept of a “safe space” to foster a sense of “trust and safety,” particularly when engaging difficult topics and conversations, I found myself questioning how safe a space I could possibly create given the risks (Hardiman et al. qtd. in Arao and Clemens, 2013, p. 138). How could I ensure that this event helped campus more than it would hurt? How could I protect my fellow participants or the audience from further strain in an already tense (and intense) political climate? In fact, Arao and Clemens (2013) suggest that a common resistance to the safe space concept is the implied “conflation of safety with comfort” (p. 135). They propose revising the term to “brave space” to reflect a more emotionally dynamic concept, one that highlights “the need for courage rather than the illusion of safety” (2013, p. 141). I quickly realized bravery, not safety, would be the heartbeat of this event.

I chose to center this experience in scholarship for the many gifts it’s given and continues to give me. Most things I learned from this one-hour event happened outside those sixty minutes. Indeed, as Diab et al. (2012) write, “In contrast to defining writing center work as a time-bound conference, we find that generative writing center work happens before, during, and beyond any timed unit of analysis and production.” I believe the sentiment reaches beyond consultations as the traditional site of writing center work and extends to any space our work may enter—or create.

While I’d like to ground this discussion in a wealth of scholarship from writing center studies, I can’t. In my research, I’ve discovered that while many practitioners engage in conversations like what I’m developing here, such communication happens in our informal spheres: blogs, listservs, and private social media groups. Practitioners discuss public events in places like WLN’s blog Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders and the Facebook group Directors of Writing Centers, where active members will be aware of common types of events such as Long Nights against Procrastination or International Write-Ins.

These conversations, however, hardly offer a comprehensive overview of such an event. With such a dearth of available descriptions, one writing center intern wrote the WCenter listserv seeking advice: although they had found some information on a particular type of writing center event, it “[wasn’t] exactly helpful for planning the event” (Scott, 2015). In addition, these conversations also center mostly on public events that support student writing by providing the space and company in which to write. While I’ve seen indications that the conversations I seek do happen in other spaces, such as conferences, I’m still in search of writing center scholarship directly addressing public events emerging from kairotic, civic moments.

The role of writing centers in society is an important issue at stake in this discussion. Although it comes to me from over twenty years ago, Nancy Maloney Grimm (1996) names a key tension in the identity of writing centers when she explains “[w]riting centers are the handmaidens of autonomous literacy—a value-free, culturally neutral notion of literacy—which although extensively challenged theoretically is still strongly at work in the academy” (p. 524). Indeed, in their activist work, other scholars have addressed resisted this persistent illusion; James A. Baldwin (2007) suggests that change—specifically, in anti-racist efforts—must be “transformational,” not “transactional” (p. 104). Engagement is an active, not passive, experience for all those participating.

In addition, I’m discovering that the experience of planning such events offers a rich site of professional development for directors themselves, although little literature has begun to explore this idea either. In Composition Forum, Rebecca Jackson, Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Nicole I. Caswell (2016) describe their research on the emotional labor of writing center administration and the “responsive attention to the emotional aspects of social life.” Gleaned from their research following nine new writing center directors, their findings suggest the “invisibility” of emotional labor leaves it “valuable yet undervalued, fulfilling yet fraught”—and its intensity often surprises and challenges inexperienced directors. Here I’d like to make my own process visible and offer a deep, sustained attention to the complex experience of creating, hosting, and reflecting on the Speaking Truth to Power WOL.

First, in Locating the Tension, I identify concepts from a variety of areas to ground my discussion. Then in Easing into the Tension, I describe the process of planning and organizing the event. Navigating the Tension offers details about how the evening of the event unfolded. Finally, Reflecting on the Tension poses some theories emerging from my experience as well as calls and suggestions for other writing center practitioners. From this exploration, I hope we can start to more carefully consider what centers stand not only to risk but also to gain from such public events.

Locating the Tension: Relevant Literature and Framing

The idea of “locating” works here on a few levels. As I mentioned, I’m processing my experience through the lens of spatial metaphors such as the “safe space” and “brave space,” describing an actual experience in a shared physical space on my campus, and—in this section—orienting my thinking in the wider landscape of available scholarship. Specifically, I’d like to frame the discussion that follows with several key concepts: emotional inquiry, a pedagogy of discomfort, and rhetorical listening.

In her work Doing Emotion, Laura Micciche (1999) writes that emotion is best thought of as performative: it’s “always already present in meaning-making activities” (p. 24). Therefore, her work suggests one can develop a capacity or skill for emotion, since it’s not something one simply has. Unlike a traditional definition of emotion as a rhetorical appeal (pathos), Micciche’s definition focuses on emotion’s rhetorical power to do things—to “shift, nudge, hurt, and heal”—as it manifests through our interactions with each other, with texts, and so on (p. 49). This lens helps clarify the potential power of events like the Speaking Truth to Power WOL: through both embodiment and the performance of emotion, speakers have the opportunity to invite intense, personal engagement, while also making their voices, bodies, and messages available to the scrutiny of an audience.

Beyond the rhetors themselves, audience members must also understand emotion as both performative and active. In fact, for audience members to participate in emotional inquiry as they process a public event, they must engage not only the details of an event but also how they experienced the event. Rhetorical instruction sometimes coaches students to pit logos against pathos, to imagine them as opposites or barriers to each other. Educator Wendy Ryden (2003) writes about the challenge of denying her students access to their emotional responses, even as readers.

While giving feedback on a particularly “angry” set of student reading reflections, Ryden says, “I responded to pathos with logos, and forced students and myself to frame emotional responses in terms of rational debate,” but she then wondered what “would have happened if I had asked people to write down not what they were thinking but rather what they were feeling?” (2003, p. 90; 2003, p. 89). Likewise, I want to consider how writing center events such as the Speaking Truth to Power WOL provide an opportunity to engage rhetoric on multiple levels; our emotional and bodily experiences of interacting with a text or performer inform how we process even the most “logical” arguments, after all.

This work, however, can get messy. I’m inclined to draw on a particular concept from feminist scholar Megan Boler (1999), arguing for a “pedagogy of discomfort” where our beliefs themselves become a productive site for inquiry. A pedagogy of discomfort not only addresses the affective dimensions required as a person grows but also the self-reflexivity required for such a process. As Julie Prebel (2016) writes of this type of pedagogy, many students recognize the connection between writing and emotion yet struggle with their uncertainty about how to handle emotional elements in the writing itself. Acknowledging the presence of discomfort becomes a crucial step in the process of emotional inquiry.

Finally, I also find the concept of rhetorical listening helpful to this discussion. Defined by Krista Ratcliffe (1999), rhetorical listening is an inventive trope that puts listening on par with the other interpretive modes (speaking, reading, and writing). She suggests it can “promote cross-cultural dialogues on any number of topics” (p. 210). Listeners can more responsibly and fully investigate how a text or performance might be operating. In fact, this process can encourage audience members to imagine the possible intentions behind a performer’s rhetorical choices and—to bridge this concept with emotional inquiry and a pedagogy of discomfort—to consider how they as audience members might be choosing to perform emotions such as anxiety, revulsion, or anger in response to the performer’s rhetorical choices.

This framing feels especially relevant in light of discussions surrounding the idea of civil discourse. Although I feel I know what the IWCA means by this concept, in their note of commitment to it following the election, I hear cries across social circles and types of media calling for a “return” to “civility,” an art seemingly lost “in today’s society.” I know what this is code for: arguments (somehow) ought to be devoid of emotion and personal perspective, which only cloud argument and prevent discussion. On my campus, I attended a forum in which faculty shared their challenges and ideas for engaging students in classroom conversations. After several people chimed in to suggest that, indeed, their own students’ emotions often prevented them from thinking logically during discussions, one faculty member shouted, “Yes! Students are just so damn emotional!” The irony of this performance of excitement and anger was not lost on me. In the wake of the election, I feel the need for these capacities to engage all the more strongly. For these reasons and beyond, I’m called to emotion, discomfort, and listening as frames—and tools—to engage intense and pertinent topics on our campuses.

Easing into the Tension: Planning a Post-Election Speaking Truth to Power Event

At our small liberal arts institution, the Writing Center serves a fairly homogeneous, residential undergraduate campus of about 1,050. In my third year as director—the only administrative position for a staff of 15 to 20 peer consultants each year—I’ve been working on increasing the center’s visibility and presence in life on campus. I’ve also been trying to center the concepts of difference and identity in consultant preparation practices to better prepare the staff for the complex and political work of a writing center. As a white, heterosexual, graduate-educated woman with a middle class background, I’ve been keenly aware of the importance of reflecting on how the center represents or fails to represent students on my campus and how the center provides or fails to provide paths of access to a variety of students. A social justice theme for a public event felt a natural endeavor to pursue as I continued to develop in my role as director.

This particular theme itself had been on my mind, though I can’t say what exact moment or inspiration led me to choose it. The phrase “speak truth to power” is used in a variety of social justice contexts as a slogan for the peaceful resistance of oppression. One of the first places the phrase appeared in print was a 1955 Quaker pamphlet, which suggests that the phrase came from Quaker teachings of the 18th century. The pamphlet, published by the American Friends Service Committee (2006), whose text is available on a website of collected Quaker materials and resources, explains that speaking truth to power involves three levels of thinking: speaking back to “those who hold high places in our national life and bear the terrible responsibility of making decisions for war or peace;” speaking back to “the American people who are the final reservoir of power in this country and whose values and expectations set the limits for those who exercise authority;” and speaking back to “the idea of Power itself,” suggesting that power is a dynamic, changing force that is socially constructed.

My hope for the social justice theme was that it would attract socially-conscious allies to alert them to what they could expect from this WOL and would at least signal to the general campus community that this event was related to social justice and “speaking back.” For an event of this nature, I wanted other entities on campus to help expand our attendance beyond the typical group of about 30 students; as a professional, I think I also sought the reassurance that if other faculty or staff sponsors agreed to work with me, it would mean that this endeavor must be a worthwhile idea after all.

This drive dovetailed nicely with another thought that had been percolating. In the 2015–2016 academic year, students on campus had created an organization called IDEA, to promote (like the acronym suggests) inclusion, diversity, equality, and access. For months I had considered asking the IDEA group to partner with the center for a WOL event. Their goals, I realized in November, could bring a powerful sense of purpose to this event in our series, and we could provide a public venue for some of their members in return.

I started planning the Speaking Truth to Power WOL by calling on the IDEA members and my own staff’s local knowledge about the campus community. During Monday afternoon, on November 14, I emailed members of both groups to seek some concrete guidance. After describing the exigency for the event, I asked them specific questions in the email: “Do you think this would fill a need on campus right now?”; “Who would you invite to speak at this event? Would you want to speak at this event?”; “What goals would you have for an event like this?”; and “What other groups would want to be invited to sponsor an event like this?” (Liebman, 2016).

In this email thread, the center, and my office, these students voiced their excitement and gave me more than a dozen names of students and faculty that the theme brought to mind; they also suggested campus organizations and departments they thought would be interested in joining forces with us.

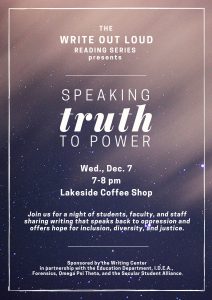

As the ideas started taking shape, I created an event poster to (hopefully) communicate something about the nature of the event in our advertising. As I’d been doing for most of our promotional materials, I used a template on Canva, a free online graphic design program. I chose a layout with a starry sky background and bright white text (Figure 2), perhaps hoping to communicate something about how our event might transcend boundaries or explore new frontiers. Or, again, maybe the choice was a bit more personal: maybe my brain thought the design reflected something about the vast and unknowable space we were entering.

With the poster prepared, I used it to entice more sponsoring organizations beyond the Writing Center and the IDEA group. Based on my consultants’ and IDEA members’ recommendations, the list quickly grew: the event was also co-sponsored by the Secular Student Alliance, the Forensics (speech) team, Omega Psi Theta sorority, and the Education Department. Co-sponsoring (strategically) required very little commitment: I told co-sponsors they would be recognized on the poster (Figure 2) and announced at the event in exchange for help promoting attendance from their respective areas of campus. That was all.

The image was disseminated digitally to the community (via all-campus email listservs and Twitter) and printed on standard-sized paper to post in public spaces on campus.

I let the co-sponsors know that, like all our WOL events, this evening would be hosted in our campus center’s coffee shop, a tiered area both industrial– and modern–looking: the higher-level cuts diagonally across one corner of the rectangular space, creating a stage-like area about three feet high. With its various seating options—including booths, couches, cocktail tables with tall chairs, and squat square tables with chairs—the area is both a site for students to socialize and a thoroughfare as they move among campus services, meals, classes, and activities. The space is more public, more dynamic, and bigger than, say, the Writing Center itself.

In the meantime, I contacted all 14 faculty members and students recommended by my staff or the IDEA group. Throughout the last two weeks of November 2016, I emailed each person to explain the event, to tell them they’d been recommended to me, and to invite them to contribute. After some discussion, three faculty members and three students agreed to participate as writers. Five of the six prepared at least some original material specially for the event, while one faculty member presented something relevant she’d prepared for a previous public speaking engagement.

Before the event, I offered all six writers my time and attention to support their drafting and revising processes. Two of the writers were comfortable proceeding with their work as it was, so I offered these two positive affirmations about the strengths I saw in their writing and ideas. A third writer didn’t ask for any specific type of feedback, so I simply offered this student a suggestion about the order in which they might perform their poems. I worked actively with the other three writers in the center or over email. I encouraged all writers to also visit with consultants in the center to continue revising their pieces, though I don’t believe any had official sessions.

My involvement with the writers differed from our typical WOL events, which function more like open mic nights: students only need reserve a time slot to participate in any of the other WOLs. Perhaps, again, my anxiety drove this decision. At any rate, as I watched everyone’s work develop, I was heartened that these six voices would be able to offer the audience a range of topics through which to experience the theme.

As the event began to take shape, I wondered how it might have come together differently than it was. My organizing principle—taking recommendations from sponsoring organizations, inviting all recommended writers, and working with any writers wanting to engage in the drafting and revision process—happened to foster voices speaking truth to power, expressing liberal ideas, and resisting oppression.

In a different version of this event, I might have made this observation and responded by proactively seeking out, say, conservative voices or individuals who met the election results with joy (an emotion not performed by any of the six speakers). Thus, the event might have included a more representative spectrum of beliefs; it might have welcomed anyone to speak any truth, no matter its relationship to oppression or privilege. This type of event would have more likely to directly addressed those students in the majority on our campus: those from conservative, rural communities, whose values might have been challenged by the event that was being shaped before my eyes.

This leveling approach, however, might have privileged comfort to the detriment of potential engagement. Arao and Clemens (2013) suggest educators rethink “safety as a prerequisite for effective social justice education” (p. 138). I, too, had to “question to what degree the goal of safety was realistic, compatible, or even appropriate for such learning” (p. 138). I couldn’t guarantee, or even predict, how this event would make a given audience member feel. I just knew I wanted to create something engaging for campus in this moment.

Navigating the Tension

The evening unfolded as smoothly as it could have. This audience was larger than our past WOL audiences. Though my opening remarks were longer and more structured that those as emcee for other WOL events, I felt calm and powerful, if a little jittery. I tried to introduce and frame the evening using the same concepts that had brought me to it: emotion, discomfort, and listening. Early in my remarks, I said:

Why did I want to organize this event, now? I fear that our campus has not done enough to help our community members practice speaking truth to power. In the wake of the presidential election, I fear that we as a community are practicing too many moves that silence or stall dialogue. I fear that we are not listening to each other.

I then offered (in a generalized way) some of the same experiences I mentioned here, to give the audience of about 50 students and faculty some context. I then led the audience through the yoga stretch called “eagle arms,” in which the arms are stacked and then intertwined front of the body, palms pressed together at the top of the tangle, because, as I told them, “there’s nothing more powerful in the fight against oppression than a white woman with a microphone talking about a thing she learned in yoga.” I explained,

Sometimes yoga is about winding, not unwinding. … I learned very quickly in yoga that if you want to stretch and grow and change, you have to dwell in a lot of discomfort first. It’s true in my teaching, too. As a woman who’s been harassed, is it hard for me to talk about sexism with my students and colleagues? No, not so much. I’ve felt it; I’ve had time to hang out with those experiences. As a white person, is it hard for me to talk about race? Yeah, sometimes. But as a person with power, if I remain silent, I become complicit with oppression. I have to have a tolerance for discomfort, for thinking out loud, for having my thinking challenging, and for listening. And I need to be able to bear witness to others’ thoughts and feelings.

And that’s what I invited the audience to do, to bear witness.

The six speakers shared topics that reflected a variety of social justice concerns, and three of the six writers explicitly discussed the election results. Writers were free to choose mode and genre, and three shared poetry while three shared prose. A student speaking about “invisible” differences, such as their atheism, tried to use their rhetoric to enlighten and provoke awareness. Another student offered a dynamic slam poetry performance, including a piece about righteous anger and race entitled “Fuck Donald Trump.” The third student also performed poetry, using metaphors about hunting and stealing a bicycle to discuss sexual assault and the objectification of women. The faculty member with the prepared presentation discussed the powerful experience of attending a ceremony welcoming new immigrants to the United States, using

audiovisual elements projected on a screen.

In all, the audience responded much as they did at other WOL events. Some people came and went as their schedules allowed; some folks stopped to watch for a few minutes on their way through the coffee shop. In that “Midwest nice” way, they clapped before and after each performance. In that slightly more interactive way, some students snapped or said, “Mmm,” in response to particularly poignant moments. As I suggested, the most powerful parts for me surrounding this event were just that: the parts surrounding. Specifically, working with the other two faculty members on their drafts and revisions was inspiring enough that I decided to conduct interviews with each of them in the months following the event. I sensed that I had more to learn from our experiences.

That night, the first faculty member, Ramesh Laungani—an assistant professor of biology—prepared and performed a poem that used the relatability of the act of shaving to explain his experiences as a sometimes-bearded “brown man” in a society where, by the weeks following the election, his fellow citizens had committed hundreds of hate crimes invoking the country’s new leader. The piece repeated the line “just like me” with descriptions of his morning routine to connect with members of the white majority through the first section of the poem before reaching a turning point that drew attention to the emotional reality and physical dangers of living in the United States as a person of color.

The final faculty member, Tim Hill—a professor of political science—wrote and read an essay narrating the ways the election challenged his pedagogy, one of checking his values at the classroom door. He explored how Donald Trump’s candidacy and now presidency forced him to consider his position not only as an authority in his field but also as a teacher wanting to engage all his students:

I remain committed to speaking truth to power, but how does one do that when speaking that truth is also an abuse of one’s own power, at least in the minds of some of those under one’s care? How do I communicate to students that there is a difference between “this policy is more conservative than I would prefer” and “this policy is a violation of democratic norms (or evidence of rank incompetence)”? How do I provide a space where all are welcome to speak their views without simultaneously contributing to the normalization of undemocratic behavior?

These faculty members’ desire to engage their students—both on campus and through this event—challenged me to dig more deeply into my experiences as a writing center director. Even as the night came to end and I thanked our speakers and audience for attending, I sensed my work was not complete.

Reflecting on the Tension: Towards Pedagogies for Making Brave Spaces on Campus

As figures with authority within the institution, I was interested in investigating how these two faculty members and I processed our own emotions (about the election and its implications for campus and our teaching) as well as how we processed the opportunity of the WOL event. In my own reflection and in the interviews with these two faculty members, I’m able to consider to the threads of emotion, discomfort, and listening more deeply—all of which lend well to spatial metaphors such as the brave space concept and literal spaces such as public events.

Emotion certainly drove the other faculty members’ experiences leading to the event as well. Laungani (2017) commented that while his own catharsis was part of his motivation to participate, he wanted to offer students a “window” into someone else’s experience: Aas a minority faculty member,” he told me, he wanted to “provide context and provide experience to our students.” My own rhetoric in my opening remarks spoke back to my sensation of fear, and Laungani suggested the event invited all the writers to air any “concerns” arising from the election results. He even suggested that this type of event would’ve been important to campus “regardless of the outcome [of the election], because of the stark differences” that this election cycle highlighted across the nation and across our campus (Laungani, 2017). This observation highlights the necessity of emotional awareness, no matter the context.

At the same time, expressing his personal concerns through his writing brought some anxiety. He feared being too “easily dismissed as a whiny liberal,” although in the poem itself he even explained, “This is not about the election results. It’s about what is a result of the election” (Laungani, 2017). Similarly, Hill (2017) feared dismissal, feared the possibility that his participation would shut down rather than engage students on campus. He half-jokingly suggested he participated “because [I] asked” and feared what it would mean “being associated with an event called Speaking Truth to Power” (Hill, 2017).

Both suggested that the event had the potential, however, of getting people in the same room and making connection possible. In fact, Laungani (2017) suggested that the Writing Center had the power to create such spaces and that as an institution, the university has an obligation “to talk about these things, but I don’t think it’s the institution’s job to make everyone kumbaya and hug.” To Laungani, projecting an intended set of positive emotions would create a “false” experience, especially compared to the exploratory opportunity that writing and speaking can provide.

Instead, people should be invited to explore and experience their role in that shared space for themselves. That’s not to say that being an audience member in such a space is an easy or comfortable role: as I’ve suggested, imagining a public, writing center event as a brave space foregrounds a challenging experience. This challenge, I believe, can be especially poignant for students in the audience while their faculty members are performing original writing. As Hill (2017) suggested to me, the challenge for us as writers and performers at the Speaking Truth to Power event was to identify the difference between “grappling with ideas that make you uncomfortable and sitting in an environment that makes you feel unwelcome;” for those of us with power and authority, “that line is so hard to walk.”

Hill’s strategy was to model the reflection he was trying to engage in his teaching. By plainly saying to the audience, “Here’s where I am,” he hoped students would be able to hear that he was not simply a “liberal bully professor” (Hill, 2017). While the event was “an opportunity to work through [his] own sense of displacement and anxiety”—calling on his own spatial metaphor—he hoped students would see the process he was trying to model. In this way, his effort echoes Boler’s (1999) call to inquire into his own affective experiences with the election, a process that disrupts before it clarifies.

Perhaps we found the work around this event especially useful because it forced us to reckon with our own positionality. “As a prof,” Laungani noted, “I’m in a position of power.” He suggested it’s “harder, particularly for our students, to be entirely dismissive of the words coming out of any prof’s mouth, whether [they] agree or disagree.” To a certain extent, this made me, as a writing center director, think more deeply about my power to create certain types of spaces, towards certain ends, for certain audiences.

I asked my own students to listen thoughtfully at the event, but I soon recognized that I needed to listen more thoughtfully to conversations in my institutional context. For instance, an editorial posted to the student newspaper’s website the same day as the event suggested campus lacked a “diversity of thought.” The next morning, reading these students’ writing, I felt defensive, as though I wanted to say, “No, you’re just not listening!” Then I heard the irony.

Indeed, Hill suggested that one implication of participating in the event was a reminder to take the time to “write [his] way out” of such tensions. As he wrote his piece and I wrote my opening remarks, we both felt the ways writing for an audience and occasion forced clarity: with the pressure and scrutiny of a potential audience, we both did our best to articulate our thoughts at that particular moment. This exercise, though, is something we as faculty—and writing center practitioners—can take up as a regular practice. It could even become a communal process among the center’s staff, a way to inquire into, develop, and share our thinking of pressing social issues.

In addition to emotion and discomfort, the concept of rhetorical listening resonated with me after the event in a more profound way than I could have imagined. I had encouraged my own students to attend and reflect on the experience—yes, by shamelessly offering them extra credit. For a chance to earn bonus points toward their course grade, I gave them until the next class period following the event to respond to the following prompt for me via email:

Tell me about a listening moment you had during this event, where you really tried not only to hear but also to understand one of the speakers. What do you think the speaker was trying to communicate? What strategies were they using? What did you feel as you listened? What do you know about yourself that might help explain whether it was challenging or easy to listen and relate to the speaker?

In a pedagogy of discomfort, rhetorical analysis requires both listening and emotional inquiry because affective experiences influence “what we choose to see and not see, listen and not listen to, accept or reject” (Stenberg, 2011, p. 361). In this rhetorical listening activity, my students confronted plenty of discomfort to answer my questions: one identified with the student who shared poetry about their sexual assault, while one talked about how they realized the limits of trying to identify with Laungani’s experience.

Looking back at the prompt I wrote, I realize my students, the other writers, and myself were up to the uncomfortable challenge of confronting our own positionalities and privileges in the process of bearing witness to each other. My students didn’t even need to use the vocabulary of privilege to process how it had affected their listening experience: I heard its role in their reflections.

I wonder how writing centers might provide more opportunities to practice emotional inquiry, productive discomfort, and rhetorical listening. Because of my specific goals for the evening, I had decided not to facilitate any public discussion during or following the Speaking Truth to Power WOL event. It’s an element I would consider at future events, however, given the relative success I felt upon reading and responding to my own students’ listening reflections.

Perhaps this would be an opportunity for other centers to create robust experiences: at such events, the emcee and consultants could prompt the audience to write on their own, then share in small groups during or after the event, or the center could provide some sort of communal writing activity such as an audience-generated poster to display in the center after the event. Directors could even invite discussion facilitators from across the community. On many campuses, representatives from multicultural centers, counseling services, communications faculty, and international studies programs could provide support for this type of activity.

I should note that in my research, I was excited to discover one interesting artifact that spoke directly to my concerns: the call for papers for the South Central Writing Centers Association 2008 Conference, in which the organizers offered the following prompts on the conference theme, “Writing Out Loud.” Although I was not involved in the conference and am unsure what work resulted from these prompts, I share them as they echo the calls I feel:

- What about writing centers makes writing out loud easier, harder, better, scary, or rude?

- To what extent do we consider our writing/student writing as a public address? As activism?

- How can a writing center work to make itself heard?

- What kinds of practices support the vocal, public writing experience?

- How can writing center directors and tutors theorize and practice the aural aspects of writing by attending to the importance of listening and/or silence?

- Can/should all writing be imagined as something to be read out loud?

- To what degree do writers/tutors/directors need to listen to what’s said/read out loud?

- How can a writing center be a place for texts to be performed/received out loud? (SCWCA, 2007)

In the spirit of these questions and more, future research should compile ideas, strategies, and themes for public writing center events, especially to the benefit of new and inexperienced directors. Such resources could paint pictures of what’s even possible in creating brave civic spaces.

I’d also like to suggest we as a community choose common terms for such events—if I could be so bold, I’ll encourage others to adopt the name “Write Out Loud” for reading series celebrating the performance of original writing—making these conversations easier to track and link across our scholarship. In time, a common set of practices could begin to form a foundation for even deeper analysis and theorizing in the future.

Engaging and Staying Open

In February 2017, members of the WCenter listserv engaged in a brief conversation considering “how writing centers might respond to this historical moment” following the inauguration. Some wrote to share how they tried to incorporate discussion about the election into staff meetings; after five days with only one short response appearing on the thread, Andrew Rihn of Stark State College replied in a way that modeled both observation and introspection:

I’ve been surprised by the hesitation and silence following [the thread’s] initial email—specifically, my own feelings of hesitation and silence. I’ve written this email in my head a bunch of times, and started writing—only to delete it—two or three times now. I feel like I should be better prepared for what is going [on in] the US, and yet I feel just the opposite.

These feelings of inadequacy mirror the discomfort I think the faculty members and I felt, too. I want these feelings, however, to become instructive, and I want us to become more comfortable with discomfort. I couldn’t have imagined the opportunities this event offered me to engage with other faculty as fellow writers, to consider the merits and risks of performance, and to invite intense experiences into our shared campus spaces.

As I continue my journey as a director, I want to remain open to the possibilities of this work. Muriel Harris wonders:

Do we choose our special areas of professional interest and research within the larger world of composition, or do they choose us? What prompts or tightens the connections that draw us deeper into one world rather than another? In what ways do we—every one of us—shape our particular corner of expertise as it shapes us? What choices were made in the process of becoming specialists? How consciously were such choices made? On what bases? What are the rewards of these choices? What parts of us have thus gone dormant or lie undeveloped? What problems and losses are incurred by the choices?

For the other faculty and I, we are now called to consider how we might best respond to kairotic moments such as the one we shared on our own campus post-election. As Laungani (2017) noted, we have to think of the ways students might be challenged as they listen to us, as they start to make that “nuanced distinction of ‘this person has studied a lot in this area and read a lot in this area and has been doing this for a long time, and so he or she has something interesting to say’ … but ‘that doesn’t mean this person is going to do everything perfectly in the classroom or even has all the answers in their field.’” This reality is something I want to remember as a writing center practitioner: public events as brave spaces might require more humility and more reflexive practice, but I will continue to write out loud to better the communities I serve.

About the Author

Caitie Leibman is the Writing Center Director at Doane University, where she teaches English courses and liberal arts seminars. She is a doctoral candidate in composition and rhetoric at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Her creative and scholarly work have appeared in New Delta Review and Prairie Schooner, and she has scholarly work forthcoming in The Peer Review and the edited collection Women’s Ways of Making (Southern Illinois University Press).

References

American Friends Service Committee. (2006, October 3). A Quaker Search for an Alternative to Violence [webpage]. Retrieved from www.quaker.org/sttp.html

Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces: a new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In L. Landreman (Ed.), The Art of Effective

Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators (pp. 135–150). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Baldwin, J. A. (2007). Everyday racism: anti-racism work and writing center practice. In Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., Boquet, E. H. (Eds.), The Everyday Writing Center: A Community of Practice (pp. 87-106). Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Boler, M. (1999). Feeling Power: Emotions and Education. New York: Routledge.

Diab, R., Godbee, B., Ferrell, T., & Simpkins, N. (2012). A multi-dimensional pedagogy for racial justice in writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 10(1). Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/diab-godbee-ferrell-simpkins-101

Grimm, N. M. Rearticulating the work of the writing center. (1996). College Composition and Communication, 47(4), 523–548.

Harris, M. (2001). Centering in on professional choices. College Composition and Communication, 52(3), 429–440.

Hill, T. (2017, March 31). Interview by Caitie Leibman. Doane University, Crete, NE.

Hill, T. (2016). speaking truth to power-Hill [Unpublished personal essay]. Crete, NE.

International Writing Centers Association. (2016, November 30). Civil Discourse and

Democratic Ideals [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://writingcenters.org/2016/11/civil-discourse-and-democratic-ideals/

Jackson, R., McKinney, J. G., & Caswell, N. I. (2016). Writing Center Administration and/as Emotional Labor. Composition Forum, 34. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/writing-center.php

Ryden, W. (2003). Conflict and kitsch: the politices of politeness in the writing class. In Jacobs, D., and Micciche, L. (Eds.), A Way to Move: Rhetorics of Emotion & Composition Studies (pp. 89–90). Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Boynton/Cook,

Laungani, R. (2017, March 30). Interview by Caitie Leibman. Doane University, Crete, NE.

Leibman, C. (2016, December 7). EXTRA CREDIT opportunity [Electronic mailing list message].

Leibman, C. (2016, December 7). Speaking Truth to Power Write Out Loud remarks [unpublished script]. Crete, NE.

Micciche, L. (2007). Doing emotion: rhetoric, writing, teaching. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Boynton/Cook.

Prebel, J. (2016). Engaging a “pedagogy of discomfort”: emotion as critical inquiry in community-based writing courses. Composition Forum, 34. Retrieved from http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/discomfort.php

Ratcliffe, K. (1999). Rhetorical listening: a trope for interpretive invention and a “code of cross cultural conduct.” College Composition and Communication, 51(2), 195-224.

Rihn, A. (2017, February 6). Re: [wcenter] WCs responding to this historical moment [Electronic mailing list message].

Scott, K. (2015, June 28). Late Night Writing Center Event Advice [Electronic mailing list message]. Retrieved from http://lyris.ttu.edu/read/messages?id=24664473#24664473

South Central Writing Centers Association. (2007, September 11). CFP: South Central Writing Centers Association 2008 Conference [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://writingcenters.org/2007/09/11/cfp-south-central-writing-centers-association-2008 conference-writing-out-loud/

Stenberg, S. (2011). Teaching and (re)learning the rhetoric of emotion. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 11(2), 349–369.