Kendra Slayton, Georgia Institute of Technology

Jeff Howard, Georgia Institute of Technology

Rocio Soto, Georgia Institute of Technology

Abstract

During the pandemic, lack of physical proximity has the potential to disrupt our work and our communities. COVID-19 has forced many Writing Centers to rethink not only the way they conduct their everyday operations, but also the ways in which consultants and administrators interact and relate to each other and their student clients. Using technology such as Microsoft Teams and video conferencing platforms, our Center has sought to implement creative strategies, including artistic opportunities and outreach events, that allow WC staff to overcome distance and continue to interact meaningfully with their fellow staff members and clients, thus fostering and strengthening our community. As a result of creative community-building during isolation, we have been able to share ourselves with each other in ways that, while different, are still meaningful. The strategies we have practiced during the pandemic, including embracing vulnerability and sharing creativity, will allow us to improve the ways we build an inviting Center community. This will not only facilitate students’ growth as communicators but also more effectively attend to their emotional and social needs–as well as those of WC staff members.

Keywords: Writing Centers; COVID-19; technology; community; games; English Language Learners; mental health; vulnerability; creativity

Introduction

Our last day before Spring Break 2020, the Naugle Communication Center’s schedule was essentially empty. As we waited for walk-ins and the few students who had reserved last minute in-person appointments, we hovered around our laptops watching the numbers of COVID-19 cases rise. We articulated anxieties, cracked jokes, colored pictures, played games, and assembled puzzles. In other words, while we waited for the university’s administration to issue the edict that our lives would no longer be the same, we in the Center continued to socialize as usual. Aaron Colton, one of the Center’s assistant directors, had accepted a job offer from Duke University and would be moving in the summer; he wondered out loud if this might be the last time he would see many of us in person.

Our last day before Spring Break 2020, the Naugle Communication Center’s schedule was essentially empty. As we waited for walk-ins and the few students who had reserved last minute in-person appointments, we hovered around our laptops watching the numbers of COVID-19 cases rise. We articulated anxieties, cracked jokes, colored pictures, played games, and assembled puzzles. In other words, while we waited for the university’s administration to issue the edict that our lives would no longer be the same, we in the Center continued to socialize as usual. Aaron Colton, one of the Center’s assistant directors, had accepted a job offer from Duke University and would be moving in the summer; he wondered out loud if this might be the last time he would see many of us in person.

It was. Or at least has been. Luckily, he and Jeff Howard, the other assistant director, had the foresight to play one more game of Scrabble the day before our collective exodus, thus dispatching a potential regret. Aaron is now in a different state, not too far from us but certainly much farther than before.

Oddly, however, the physics of distance no longer seem to be measured in terms of far and near; distance, in large part, simply is. Characterized not so much by long but by longing. Inconvenient, insurmountable, irrefutable.

One of the many challenges of this new physics concerns the ways we navigate our lack of physical and emotional proximity. We throw around the metaphor of family a lot in our Center, but with virtual communication through videoconferencing this metaphor has taken on a different dimension. Before the crisis, we socialized and shared within the confines of the Center’s physical space. In fact, as Emily Nguyen, one of the student consultants in the Center, recently expressed, “At our core, we are sharers [emphasis added]: sharers of stories, of skills, of research, and of time.” The socially distanced dynamics of our interpersonal relationships have complicated the act of sharing, but those complications have also led to creative new ways of sharing and of improving our consultation practices. Now we experience–frequently–the vulnerability of inviting and welcoming each other into our living spaces, our home offices, dining areas, and even bedrooms. In our collective isolation, like a family, we embrace to variable degrees that vulnerability, as we continue to find opportunities to share our stories, skills, time, and talents with each other and our students.

The Physics of an Online Community

When our lives suddenly changed and work went online in the spring, initially, there was very little time to think about how to transfer our tight-knit sense of community to a digital space. Most of us spent our days in triage mode. It was hard enough to struggle with the fears ushered in by the nascent pandemic while emergency planning how to operate our Center online. Simultaneously, our student workers were mourning the loss of in-person experiences while adjusting to a full slate of online classes.

The fall semester offered a bittersweet mix of relief and grief. While we were able to do our WC work from the safety of our homes, we were also missing out on valued social aspects of that work, such as collaborating on Center events and learning from each other’s tutoring styles through informal observation and discussion. The everyday things, in their absence, turned out to be some of the most important––playing impromptu Scrabble games, sharing anecdotes from our classes, or talking about our hobbies and creative endeavors. Collectively, we missed sitting in our quirky Center decorated with a disco ball; a cardboard cutout of David Tennant as Dr. Who; and paper narwhals, the unofficial mascot of the Center. (It’s a long story.)

In addition to its bittersweetness, however, the onset of the fall semester also offered a fresh start and a renewed desire to recreate those little Center moments as much as we could in our strange new world. In late August, one of our professional consultants, Alok Amatya, who had been piloting Microsoft Teams successfully with his own students, recommended that we use the platform as a way for WC staff members to stay in touch. While we were still having our usual weekly staff meetings through video conferencing, a Teams space seemed like a way to accommodate additional points of contact. We started off small––just a “General” channel for quick questions and another channel for sharing funny memes, as we all felt we could use a bit of humor. Kendra Slayton, our new assistant director after Aaron’s departure, created a custom logo for the Teams space––a narwhal in front of a disco ball––to provide a small reminder of the ethos of the physical space we normally share. We soon realized that the online Teams space could become an avenue for nourishing our sense of community even in isolation––a way to simulate the kinds of friendly encounters and spontaneous conversations that we would have organically in the Center.

In addition to its bittersweetness, however, the onset of the fall semester also offered a fresh start and a renewed desire to recreate those little Center moments as much as we could in our strange new world. In late August, one of our professional consultants, Alok Amatya, who had been piloting Microsoft Teams successfully with his own students, recommended that we use the platform as a way for WC staff members to stay in touch. While we were still having our usual weekly staff meetings through video conferencing, a Teams space seemed like a way to accommodate additional points of contact. We started off small––just a “General” channel for quick questions and another channel for sharing funny memes, as we all felt we could use a bit of humor. Kendra Slayton, our new assistant director after Aaron’s departure, created a custom logo for the Teams space––a narwhal in front of a disco ball––to provide a small reminder of the ethos of the physical space we normally share. We soon realized that the online Teams space could become an avenue for nourishing our sense of community even in isolation––a way to simulate the kinds of friendly encounters and spontaneous conversations that we would have organically in the Center.

Sharing Creativity: Theme of the Month

Community does not automatically arise only because consultants engage in the same kind of work. It also emerges from the informal conversations, interactions, traditions, and relationships we build and share between sessions. One of the initial ways that we began using Teams to maintain and build our sense of community involved the creation of a “Theme of the Month” channel. Near the beginning of August, Kendra was brainstorming for her upcoming class syllabus and found herself doodling in the margins of her notes. The doodling became an hour-long art session. At the end of it, Kendra was surprised by how refreshed she felt. She had not done much art in years, and it had felt incredibly therapeutic, clearing her mind of the concerns provoked by the prospect of an all-online semester during a pandemic. The doodling was also the kind of thing that we might find ourselves doing in the Center between appointments; for example, we used to bedeck our whiteboards with little notes to each other, encouraging phrases, or seasonal drawings. Kendra’s doodles and the accompanying restorative feeling inspired her to create a “Theme of the Month” channel for the whole WC staff. Its purpose included providing a creative, therapeutic outlet to help staff stay connected with each other despite the distance. For each month, the idea was to collectively choose a specific theme (for example, “nature”). Over the course of the month, anyone who wanted to could submit a response to the theme. Media could include drawings, photographs, poems, videos, and so forth.

The first theme, for October, was “Autumn.” Early submissions included photos of pumpkin-flavored baked goods and fall-themed arts and crafts. Toward the end of the month, we shifted to sharing the little ways we were celebrating Halloween at home, including carved pumpkins and spiderweb nachos. Emily even shared the costume photoshoot she did with her sister.

Quite popularly, Alok also shared pet costume photos and hosted a poll for Center staff to vote on which costumes his dogs, Cheeko and Luna, should wear for Halloween.

All these posts, in their way, reenacted the kinds of community-building events that normally occur in the physical Center––sharing baked goods, working on erasure poems between appointments, or gathering for a Halloween potluck and costume contest.

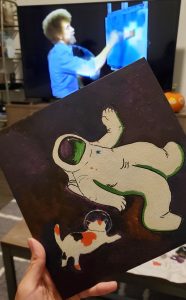

For November’s theme we chose “Survive.” We knew that our professional and student staff members alike would soon be facing the pressure of a sharp increase in Center appointments in addition to the looming stress of final projects and exams. The responses to this theme were just as creative as those for October. Kendra, for example, shared a picture of a breakfast feast with the advice, “Fueling up is the key to survival!” Emily posted a picture she had painted of a cat astronaut while watching Bob Ross, along with a recommendation to turn to art to de-stress.

For November’s theme we chose “Survive.” We knew that our professional and student staff members alike would soon be facing the pressure of a sharp increase in Center appointments in addition to the looming stress of final projects and exams. The responses to this theme were just as creative as those for October. Kendra, for example, shared a picture of a breakfast feast with the advice, “Fueling up is the key to survival!” Emily posted a picture she had painted of a cat astronaut while watching Bob Ross, along with a recommendation to turn to art to de-stress.

These new ways of creating community through a digital space certainly enhanced the mental health of our entire staff. In addition, they also reminded us of our core mission–in every consultation, we create a mini-community between client and consultant. The student clients who come back to us do so because of the quality of the relationships we build with them. As with our own internal staff relationships, we have had to learn how to adapt our relationship-building strategies so that our clients would be more comfortable in an online space. Our staff activities on Teams have made us more adaptable digital communicators, which has allowed us to become more effective “sharers of stories.” This increased facility with digital communication has allowed us to help our clients share their stories with us during virtual consultations.

Sharing Vulnerability: Max’s Movies

In addition to increasing our general facility with digital communication, our online space has increased our understanding of the role vulnerability plays in growing communication skills. This, in turn, has allowed us to practice creating safer online spaces for our students to be vulnerable in.

One of the ways we have practiced vulnerability through our online Teams space is through embracing the already thin line between personal and professional. For example, Jeff’s three kids (who are all age six and under) are constantly interrupting his video conference meetings. Consequently, nearly everyone who knows Jeff professionally also knows Max, Jack, Chris, and Penny personally. They barge into WC staff meetings to say hello, steal his headphones, and share pictures they have drawn. It does not matter who is on the other side of the video conversation; the kids want to participate and engage. Because of the pronounced proximity of his personal and professional life, Jeff not only invites people into his home but really shares his entire family with his coworkers, including their moods and their accomplishments.

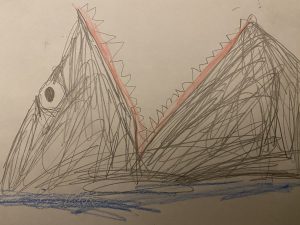

Jeff gradually embraced the vulnerability of his family’s unavoidable presence, and even saw it as an opportunity to help his children learn about the importance of vulnerability in growing their creativity and literacy. This led to the directorial debut of Jeff’s oldest son, Max. His first homemade movie appeared on our November “Survive” channel.With Jeff’s help, Max continued sharing his homemade movies about sharks (and other subjects that many six-year-olds love), including a stop-motion production Jeff refers to as “The Year in Retrospect.” Max drew all of the pictures, picked out music and colors and titles, and created storylines. Jeff helped him by doing the editing and other technical work, and together they assembled a substantial oeuvre. Each time their collaboration produced a new movie, staff meetings and the Theme of the Month channel became venues for sharing Max’s work with an audience. Not only did the members of our WC family receive the opportunity to witness a significant stage in Max’s development, but because of their enthusiasm and validation for works such as “Dinosaurs,” “Cardboard People,” and “Dolphins and the Angel Fall,” they became participants and facilitators in his developing creativity. This is––not coincidentally––exactly the function we, as communication consultants, serve for the clients who visit our Center.

Jeff gradually embraced the vulnerability of his family’s unavoidable presence, and even saw it as an opportunity to help his children learn about the importance of vulnerability in growing their creativity and literacy. This led to the directorial debut of Jeff’s oldest son, Max. His first homemade movie appeared on our November “Survive” channel.With Jeff’s help, Max continued sharing his homemade movies about sharks (and other subjects that many six-year-olds love), including a stop-motion production Jeff refers to as “The Year in Retrospect.” Max drew all of the pictures, picked out music and colors and titles, and created storylines. Jeff helped him by doing the editing and other technical work, and together they assembled a substantial oeuvre. Each time their collaboration produced a new movie, staff meetings and the Theme of the Month channel became venues for sharing Max’s work with an audience. Not only did the members of our WC family receive the opportunity to witness a significant stage in Max’s development, but because of their enthusiasm and validation for works such as “Dinosaurs,” “Cardboard People,” and “Dolphins and the Angel Fall,” they became participants and facilitators in his developing creativity. This is––not coincidentally––exactly the function we, as communication consultants, serve for the clients who visit our Center.

By being vulnerable in WC meetings and our Teams channels, Jeff introduced his son to new situations and audiences that could foster his development. Jeff also helped everyone else learn the value of vulnerability when communicating and consulting. In our WC work, of course, we ask this vulnerability of our student clients in every session. By flipping the script and embracing vulnerability ourselves as consultants, we can break down the binary between acting like an editor and acting like a peer. An editor might consider themselves the ultimate authority, whereas a peer negotiates and transparently embraces the limits of their own understanding with their student clients. Through shared vulnerability, we invite clients to a safe space where they can ask questions and become active participants in refining their work.

Sharing Transitions: Adjusting to Change Together

Vulnerability is also essential for integrating new members into a community even in “normal” circumstances. On the one hand, new members are in a vulnerable position as they try to join and navigate an established community. On the other hand, existing members of that community likewise must show vulnerability to really open their community to the new member. Unsurprisingly, trying to integrate new members into a community during remote work can present additional challenges. In the Fall 2020 semester, the Center was only able to hire one new consultant due to recent budget cuts; all of the other consultants knew each other from before the pandemic forced us into isolation. Eric Lewis, the new professional consultant, was still in South Bend, IN, and all of our interactions with him occurred via video conferencing. He had plenty of opportunities to acquaint himself with other professional consultants (who are postdoctoral fellows like him) in faculty meetings, but his opportunities to develop connections with the student consultants were limited.

To help integrate Eric into our community, we invited him to an online student consultant meeting near the beginning of the semester so that he could meet everyone and introduce himself. Afterwards, we proposed a collaborative publication project in which Jeff and Eric would interview the student consultants about their experiences and reflections on the shift to online consultations. The hope was that through these interviews, Eric would start to develop a rapport with the consultants even though he could not have the sustained in-person engagement that many of us had relished. These sessions put both Eric and the student consultants alike in a vulnerable position. On the one hand, Eric asked students to specifically convey their experiences during the remote shift–including their negative experiences–which is intimate information to share with an outsider. From the perspective of the students as representatives of the Center, there was risk of sharing something that could be misinterpreted. On the other hand, from Eric’s perspective, there was pressure to represent himself, a relative outsider, as friendly and approachable, while also acting as a formal interviewer. This shared vulnerability, however, was a catalyst for building rapport and community. Eric enjoyed the opportunity for one-on-one interactions through email and video conferences with these consultants. Additionally, he also shared in their professional development; the resulting piece was for all the students their first publication in WC studies.

This project was an opportunity for community-building at a time when the kinds of projects that we had done in the past to build community were no longer available to us. Due to pandemic budget constraints, the Center could not replace student consultants who had graduated, and we had to repurpose professional development hours into consulting hours for remaining student consultants. Previously, during these hours student consultants were able to collaborate with each other, professional consultants, and clients to promote and improve the Center’s services, such as designing public exhibits or medical school application workshops. Many of these projects led to vital community building for our student consultants and even initiated key Center traditions. It was also through these projects that students were able to co-create an environment within the center conducive to their mental and emotional health. However, with the temporary hiatus of development hours and the increased workload due to understaffing, the emotional and mental health of students became an increasing concern. In WC work, you have to be “on” for the duration of each consultation and be emotionally available to student clients–something very difficult to do if you are emotionally drained yourself.

Supporting consultants’ emotional well-being and promoting community building in an online space requires innovative thinking. As a result of our situation, Lead Student Consultant RocioSoto had to reevaluate the student consultant meeting format of previous years to address the consultants’ needs in these areas. Instead of focusing on training, something all the current consultants had already received, she reoriented the meetings to a more open forum-based discussion where students could bring questions and concerns regarding online consulting. She also began to integrate games at the end of each weekly meeting. The games became a crucial strategy for improving student mental health and building community. From virtual Pictionary on Skribble.io to Wiki Relay, a game in which players attempt to find a word by clicking hyperlinks in Wikipedia pages, each game focused on encouraging the student consultants to engage with each other. These games gave us the chance to talk to each other more organically than in a formal meeting, like we used to do in person. They also gave us an opportunity to emotionally recharge by having fun. Ultimately, the games helped us to continue building community with each other and remain emotionally available to our students during consultations.

Supporting consultants’ emotional well-being and promoting community building in an online space requires innovative thinking. As a result of our situation, Lead Student Consultant RocioSoto had to reevaluate the student consultant meeting format of previous years to address the consultants’ needs in these areas. Instead of focusing on training, something all the current consultants had already received, she reoriented the meetings to a more open forum-based discussion where students could bring questions and concerns regarding online consulting. She also began to integrate games at the end of each weekly meeting. The games became a crucial strategy for improving student mental health and building community. From virtual Pictionary on Skribble.io to Wiki Relay, a game in which players attempt to find a word by clicking hyperlinks in Wikipedia pages, each game focused on encouraging the student consultants to engage with each other. These games gave us the chance to talk to each other more organically than in a formal meeting, like we used to do in person. They also gave us an opportunity to emotionally recharge by having fun. Ultimately, the games helped us to continue building community with each other and remain emotionally available to our students during consultations.

Sharing Community: Expanding Student Outreach

Of course, Center staff were not alone in adjusting to a remote semester; we also shared this transition with our student clients, who are vital members of our Center community too. We were particularly conscious of the loss of community for our English Language Learner (ELL) and international student clients. The sudden transition to online learning during the spring semester was particularly chaotic and even painful for many of them because of confusing directives from the university. Furthermore, national visa and immigration policies seemed to be changing on a daily basis well into the summer, and troubling Anti-Asian sentiment and xenophobia were fomenting locally and nationally.

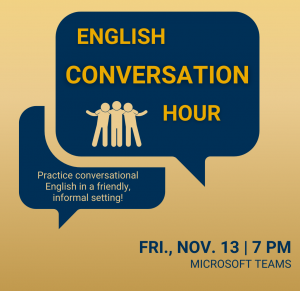

Our Center has long been committed to serving ELL students, particularly with the hire of our current ELL specialist, Rob Griffin. In September 2019, Rob worked with Kendra to pilot an English Conversation Hour program; once a month, we invited ELL students to come to the Center for an hour of snacks, friendly conversation, and communication-themed games. Given the traumatic climate many of these students were facing in the wake of the pandemic, it was important for us to clearly communicate to these students that they were valued and welcome members of our Center community. Rob and Kendra worked together to offer a video conferencing version of Conversation Hour in April and May 2020.

While it was difficult for students to attend these spring sessions during the sudden transition to online learning, the start of the Fall 2020 semester offered another opportunity to redesign and advertise the program for the online format. Kendra created a Microsoft Teams space for Conversation Hour participants, including separate channels that could function as breakout rooms. Each event has included ELL students, professional consultants, student consultants, and Center assistants. We typically begin with the whole group in the main call and some general small talk. Participants then receive a list of 2–3 potential conversation topics (for example, “What’s your favorite place to visit?” or “What do you like to do to de-stress?”). We then split into breakout rooms of 3–4 people. Each room is facilitated by either a Center staff member or one of our campus partners in the student International Ambassadors program.

While it was difficult for students to attend these spring sessions during the sudden transition to online learning, the start of the Fall 2020 semester offered another opportunity to redesign and advertise the program for the online format. Kendra created a Microsoft Teams space for Conversation Hour participants, including separate channels that could function as breakout rooms. Each event has included ELL students, professional consultants, student consultants, and Center assistants. We typically begin with the whole group in the main call and some general small talk. Participants then receive a list of 2–3 potential conversation topics (for example, “What’s your favorite place to visit?” or “What do you like to do to de-stress?”). We then split into breakout rooms of 3–4 people. Each room is facilitated by either a Center staff member or one of our campus partners in the student International Ambassadors program.

Our revamped, online English Conversation Hour has been a great success. Before the pandemic, we averaged 5–10 participants in each Conversation Hour. The online format has allowed us to extend our reach, and we now average 10–20 participants in each event. Our participants are happy to talk with one another in a live but informal space. The event offers our ELL student clients a chance to synchronously practice English conversation during an academic year sorely lacking such community-building opportunities. Additionally, we have found that Center staff greatly benefit from the event as it offers an opportunity to form meaningful relationships despite social distancing. While we are not sharing a physical space, through Conversation Hour, we can nonetheless share much of the emotional space that makes the Center so special. We can collaborate to implement the event; overhear how other consultants talk to students, thus refining our individual tutoring styles; and most importantly remember that even in isolation, we can always find a community through the Center.

Conclusion

In the past, we relied on physical proximity and coinciding schedules for communal connection; who you worked with was who you got to know the most. Now that these coincidences no longer throw us together like quirky characters in a Nora Ephron film, we have resolved to become more intentional in building and maintaining our Center community. One key takeaway from this ongoing experiment in the technological mediation of human relationships is that while the immediacy of our former interactions is diminished, the quality of our relationships is not. Indeed, we would argue that our desire to fill the void produced by physical distance has motivated many of us to share more of ourselves than ever. We anticipate that these new technological solutions and strategies for creative sharing and community building will continue to exist and function in tandem with our in-person interactions within the Center’s physical space.

Furthermore, through these experiences, we have developed practices that we will carry forward into our WC work long after the pandemic ends. This unique year has taught us the importance of innovative thinking in our professional and personal lives, as well as the value of collapsing the line between those lives. Having seen the impact of vulnerability on our work and our ability to affect the lives of our student clients, we will continue to practice this important characteristic in our sessions, whether by having franker discussions about the messiness of the composition process during consultations or by sharing our own work during Center events. In doing so, we can invite student clients to likewise embrace their own vulnerability and form a peer relationship rather than a hierarchical relationship in each consulting session. Ultimately, establishing this kind of peer relationship encourages the exchange of stories between us and our students, which in turn allows us to identify and utilize creative approaches to communication. This openness likewise fosters individual and collective well-being; positive and memorable rapport between clients and consultants; and a welcoming environment to which our clients will be more likely to return.

In the early days of the pandemic, we feared that we would not be able to share ourselves with each other anymore. These fears, however, have blossomed into a facility with new ways of communication that enables a closer community than eve–both among Center staff and with our clients. Rather than our sharing being centered around our physical Center, we learned that our sharing is at our core no matter where we are. The community that we have become in isolation has not been simply a temporary alternative to the kind of community we used to be. Rather, it has shown us a more fully realized version of the community we have always been and how we can more intentionally share that community with our students.