Adrian R. Salgado, Florida International University

Xuan Jiang, Florida International University

Abstract

In this reflective paper, the authors share the trials of their writing center’s graduate writing program as it transitioned from fully physical and in person pre-COVID to fully virtual during COVID. The graduate writing program aims to help establish a channel for graduate students from the stage of completing coursework to that of completing graduate degrees when attrition is likely to happen. With four semesters and three phases, the current writing group program includes the following features: multitudinous collaborations, allocated space, appropriate accountability, and progressive reciprocity. These features have increased student retention and improved student isolation, creating opportunities for companionship in academic writing. As a result, this has increased the success of participating graduate programs. The authors’ accumulated reflections contribute to writing center practice with the aim of developing similar writing support programs in other centers and contributing to writing center scholarship as another layer of experiential introduction to more Replicable, Agreeable and Data-supported (RAD) research studies.

Keywords: multitudinous collaborations, allocated space, appropriate accountability, progressive reciprocity

Introduction

Just as Amy Whitcomb (2016) found in her case study, many graduate students pursue their graduate programs as if on an isolated island, only attending their classes and meeting their major professor as go-to support. As a result, many graduate students feel frustrated, anxious, and even depressed. Without support, students are unable to complete their programs within the required years because of the obstacles in completing theses, dissertations, or capstone writing projects (Kells, 2016). Hence, it is necessary to provide systematic and ongoing support for graduate students beyond the classroom or faculty mentorship (Harris, 1982; Kells, 2016) in order to foster “professionalism” and “persistence” in graduate degree programs (Bell & Hewerdine, 2016). One sort of the aforementioned support—a writing group—has been discussed, studied, and merited as a “safe space for cultivating a culture of collaboration and critique among graduate students as colleagues” (Kells, 2016, p. 28; Mannon, 2016).

As discussed in the literature, writing groups are most typically hosted in writing centers (WCs) and facilitated by consultants (e.g., Bell & Hewerdine, 2016; Mannon, 2016). In order to implement the practice, however, WCs need more concrete details to ensure the success of the program and the students they serve.

In this paper, the authors will introduce existing literature pertaining to their writing group—Graduate Writing Mentorship Program (GWMP). In order to situate this discussion, the paper will begin with the exigence for the GWMP. Then, they will describe the evolution of the GWMP, a weekly three-hour-long writing group, while sharing their thoughts, reflections, and critiques in the form of proposed take-aways and best practices. The discussion of the GWMP, as well as its successes and failures, is intended to inform other WC practitioners of more contextual considerations for such programs in order to contribute to existing WC practice. Additionally, it is the author’s hope to inspire potential RAD research, as advocated for decades by scholars, including Harris (1982) and Driscoll and Powell (2015).

Four Features of Writing Groups from Literature

Writing groups are one of the approaches to addressing “the intersection of writing, student, tutor, professor, and graduate school” (Whitcomb, 2016, p. 87). Extending the support from faculty’s own vision (Kells, 2016), it “meet[s] the expanding expectations of graduate school and various professional communities” (Remmes Martin & Ko, 2011, p. 12). Features of writing groups include “personal goal setting, timelines, and accountability…navigating relationships and networking…knowledge-sharing…encouragement” (Remmes Martin & Ko, 2011, pp. 14–15). Building upon this discourse, the authors will elaborate on the following aspects: multitudinous collaborations, allocated space, appropriate accountability, and progressive reciprocity.

Multitudinous Collaborations

One of the main benefits of having multidisciplinary writing groups rather than discipline-specific groups is that “[s]ince students bring different disciplinary knowledge to the table, less emphasis is placed on knowledge linked to a particular discipline, and students can perform as experts within their own disciplines” (Brooks-Gillies, Garcia, & Manthey, 2020, p. 201). In addition to the students themselves, the consultants leading the groups also benefit from multidisciplinary perspectives. By understanding the different types of academic writing styles and research topics, consultants are able to carry this knowledge from the writing groups into their work in the WC. One strategy is novelty moves as “a flexible heuristic used in diverse academic disciplines,” which empowers tutors to engage with writing beyond their content background (Reineke et al., 2018, p. 168). Reineke et al. (2018) mentioned a handout in their chapter, which is from Student Academic Success Center at Carnegie Mellon University, to show how to establish novelty with four rhetorical moves: explain significance, describe the status quo, identify a “gap,” and fill the gap with your current research. Novelty moves can also help develop expertise to equip consultants “with strategies for stimulating student learning” (Bitzel, 2013, p. 1). As tutors gain different perspectives from the students in the groups, they also share their own unique research and writing experiences.

In addition to cognitive enlightenment or enrichment of the writing group participants, the benefits of such multidisciplinary collaborations also involve emotional comfort and support via “empathic listening and responding” (Costello, 2018; McBride et al., 2018, para. 1). Such support reflects the WC philosophy of acknowledging that academia is not emotion-free and regarding students as “people first and writers second” (McBride et al., 2018, para. 2).

Allocated Space

Brooks-Gillies et al. (2020) emphasize allocated space and describe how “the groups provide a particular kind of space: one in which graduate students from across disciplines can talk about their writing, their advisors, their classmates, and their non-academic lives without the stress of assessment and disciplinary judgment” (p. 206). Brooks-Gillies et al. (2020) share the same thought about the merit of such spaces and highlight that “they provide support and community, structure and accountability, and multidisciplinary perspectives to their participants” (p. 191). The spaces can be even therapeutic in “negotiating the discourses, conventions, and expectations of multiple faculty, disciplines, and students” (Costello, 2018, para. 11), with its “openness, hyper-awareness, attentiveness, and self-reflection” (Costello, 2018, para. 22). With guidance from a mentor within the same space, reaching writing goals allows graduate students to generate and maintain the motivation needed to complete their projects.

As Bell and Hewerdine (2016) state, “[a] combination of formal and informal groups may help students to find the community of writers that works best to move them towards completion” (p. 51). The advantage of such a community includes “providing motivation and encouragement to each other” and “sharing knowledge (e.g., resources, literature, teaching strategies, research methodologies, and statistics)” (Remmes Martin & Ko, 2011, p. 13). The WC, as the third space (i.e., not in class or off campus), can be and should be an extended academic contact zone beyond classroom or mentorship discourse. In this “egalitarian relationship” (Rollins, 2015, p. 3), the WC discourse predominantly “situates the tutors as peers” (Bitzel, 2013, p. 1). Peer tutors are more coaches and collaborators than instructors (Harris, 1982, p. 6), generating “more intimate and personal” communities (Rollins, 2015, p. 3). They serve “as agents of emotional, psychological, and personal support” (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012, p. 79). These types of allocated spaces are essential to student success but are most effective when paired with accountability.

Appropriate Accountability

In the context of a writing group with allocated space, embedded accountability “provide[s] consistent scholarly, human [virtual] contact which…can help students completing exams and dissertations maintain productivity” (Brooks-Gillies et al, 2020, p. 201). The accountability in the writing groups is necessary to keep students on track because the consultants are able to meet with the students and ensure progress between the student’s meetings with their advisors. Such a structure has demonstrated efficiency and higher retention of enrolled graduate students.

Accountability leads to retention which is the key to graduation. Retention secures graduate students’ continuity of their programs till graduation; attrition, as an antonym of retention, is a universal crisis in graduate programs. Bell and Hewerdine (2016) discuss the role attrition plays in academia and the standing of graduate students within it by stating, “[g]raduate students transitioning to becoming scholars may lack a strong sense of self or their identities as scholars, creating challenges to writing impacted by shifting agency in a liminal place in academia” (p. 51). Along with the transition, students who have completed their coursework and moved to the thesis/dissertation stage often feel lost and powerless along their journeys of such high-stake academic writing. Within writing groups, graduate students meet and work with other students to reach their ultimate goals of becoming scholars. In turn, this long-term empowerment helps the students gain agency and self-efficacy (Bell & Hewerdine, 2016). Additionally, within the writing groups, students share individual struggles and vulnerabilities which decreases isolation and stress through companionship and reciprocity.

Progressive Reciprocity

Graduate writing groups aim at generating and maximizing benefits of reciprocity in “a horizontal process” within peer collaboration; this idea is supported by the research of Emma Flores-Scott and Maresi Nerad (2012, p. 74) and more recent research of Katrina Bell and Jennifer Hewerdine (2016). According to Flores-Scott and Nerad (2012), the role of peers in graduate study should be classified as “learning partners” (p. 81). This is effective because “[e]mphasizing mutual learning between peers can in fact help better prepare doctoral students for the role of an academic, in which practices like peer review are used regularly” (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012, p. 81). Similarly, in their research, Bell and Hewerdine (2016) provide an explanation for the aforementioned idea that the motivation to conduct collaboration with peers is vital for students to understand their role as scholars within and outside their fields (p. 53). Reciprocity allows for both the mentors and the graduate students to engage with each other in discourse about writing. While keeping accountability as the main concern, these groups are able to focus on how to write effectively and mostly achieve the writing goals those students set for.

By being classified as “learning partners,” there is a stronger focus on reciprocity. In the sessions the mentor and the mentees are constantly learning from one another and so are the mentees amongst themselves. For instance, mentees feel comfortable sharing their drafts and internal reviews before submission for publications; and, mentors practice and reflect on the tutoring strategies across disciplines and beyond writing. The practices and reflections of the consultants contribute to the profession and WC scholarship (e.g., the current paper). Such reciprocity in progress essentially transforms individual writers’ solitude into companionship. In this way, they feel less alone on their writing journeys and are less likely to give up. This leads to less student attrition and more student success.

Exigence

Florida International University (FIU) is a large public research university with an enrollment of over 56,000 students, of which over 8,000 are graduate students. It is also a commuting university where approximately 90% of its students live off campus. Many of the graduate students who work and live locally visit campus only for class; as a result, they are more likely to lack awareness of the on-campus resources, underuse their advisors’ office hours, and delay forming their peers’ academic network. During a meeting to better meet graduate students’ writing needs with the associate dean of FIU’s graduate school in Fall 2019, the second author, Xuan Jiang, proposed the idea of adding a graduate writing group as a weekly activity to the existing regular consultation service; both were free to all students, hosted in the WC. So, the graduate writing group started in November 2019 and continued thereafter. With the goal of using this pilot program to learn and grow, the three main factors under consideration throughout and moving forward were exit survey results from the GWMP participants, the feedback from facilitating graduate consultants, and the GWMP retention rates.

Overview of the GWMP in Three Stages

The final stage of the GWMP stemmed from three evolutionary stages, where the first stage had a more informal structure, and the current stage had more formality and organization in terms of attendance and accountability. The following will introduce the initial stage through the most current one and the features of each.

The initial writing group program aimed at providing a physical space and maximizing time for writing. A graduate consultant provided minimal intervention, and there was no cohort formed. The name of this program was called the Graduate Writing Circle. It was created on the basis that graduate students had a set time (i.e., three hours on Fridays) for writing without any distractions. The consultant served as a mentor and answered any questions that arose. All graduate students who had received the information via email about the circle were free to come. It was a come-and-go mode, so graduate students came and left freely. The turnout ranged from 6 to 14 students on those Fridays. This stage had high attrition and low returning rates, as seen from their sign-up forms.

The second stage of the writing group program was then named the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program (GWMP). The program took place fully online because of the university’s transition to remote learning in March 2020 due to COVID-19. This stage began the use of a virtual format using Zoom with an application-based cohort. Two cohorts composed of one graduate consultant to twelve graduate students were formed. No attendance was required, consultants left their cameras off, and many students simply utilized this service as they had previously, coming briefly when needed for a few minutes of feedback. The retention rate was very low (i.e., below 20% from the consultants’ records) and so was the response rate of the exit surveys which was shared by FIU’s graduate school.

With the progression of the two initial stages, the authors learned which features of the writing group program are more likely to yield success of the current GWMP. The current GWMP, which was piloted in Summer B 2020 and officially implemented from Fall 2020, added attendance regulation and withdrawal consequences of two unexcused absences. Predicting more and longer conferences with each student and the heavier workloads for the consultants, the WC secured more support from FIU’s graduate school. Using this additional funding, three cohorts, consisting of one graduate consultant to 10 graduate students, were formed. These groups met weekly for three hours on a chosen day of their preference. Revealed in participant conference responses and surveys, graduate students were better able to regulate their writing schedules and manage their writing progresses. In addition, another favorable outcome included the fortification of participants’ writing mindsets and behaviors through metacognitive enhancement. Equally importantly, the beginning and ending conversations of the whole cohort provided a relaxing platform for them to share feelings and exchange resources, strategies, and experiences; the peer network developed in this program helped participants be more engaged and more strategic for their writing progress. Overall, the current structure of the GWMP has been most successful. The three-hour-long weekly activity was useful, manageable, and enjoyable according to participants’ reflection and feedback.

A Close Look at the Current GWMP

The current GWMP consisted of three virtual cohorts which took place on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. The graduate consultants sent reminder emails one day in advance with a sign-up sheet for the individual meetings. At the beginning of each three-hour session, the consultants welcomed every participant in the main room. This was followed by a five-minute free write, any announcements, and general questions. Based on the sign-up sheet, the consultant then conducted one-on-one conferences with each student using Zoom breakout rooms (see Figure 1).

While the individual conferences occurred in the breakout rooms, the other participants stayed in the main room and continued to write (for session notes, please see Appendix B). If they had questions, they wrote them in the chat. Upon returning to the main room, the consultant read the questions and either immediately responded in the main room or addressed them individually in that student’s conference. In addition, the group also used the chat to share resources. The synchronous and asynchronous communication kept the community and moved the participants’ writing forward. Students could apply a maximum of 150 minutes to writing with scaffolding when needed.

The last 20 minutes were saved for a group wrap-up. One of the routine activities was to ask individuals to share the word of the day. For example, some students chose “positivity,” “controversy,” and “imagine” as their word of the day. The word would be followed by the participants’ explanations of how they used the word to speak about their writing or other relevant factors affecting their writing on the day. That time period formed a relaxing virtual forum to share, value, and appreciate each members’ feelings and thoughts. A celebratory coda every week motivated students to continue this program and their writing progress.

Best Practices for Other Writing Centers

These iterations improved over time and allowed for multitudinous collaboration, allocated space, appropriate accountability, and progressive reciprocity. With each version, these frameworks became more central to the development of the current writing program and its success. When forming a graduate writing group, WC directors or other partnering contingencies may consider the following factors:

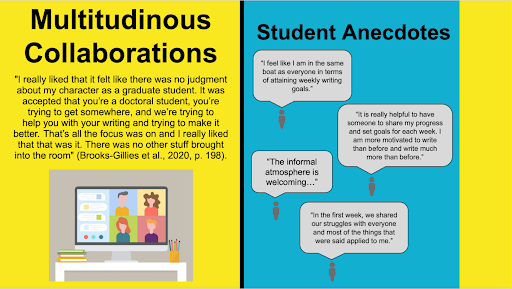

Practically, multitudinous collaboration has two foci—one-on-one conferences and valuing participants’ voices. Breakout sessions with one-on-one conferencing ensure that the student is progressing with their writing on a weekly basis. Creating weekly goals allows for graduate students to break down a high-stake writing project into achievable low-stake chunks and make their way along its completion. The participation of graduate consultants communicates that graduate students are not alone, have community, and are supported throughout the process by peers in addition to advisors. Consultants also bring their “personal and social identities” as well as their emotional support in the cohort (Bitzel, 2013, p. 2), via “empathic listening and responding” (Costello, 2018; McBride et al., 2018, para. 1). The current GWMP also promotes engagement in the beginning and the end of the program without taking too much time from writing. If participants have any general concerns, questions, or would like to discuss any writing resources that they may have found helpful during their week of writing, they can share them with others. Some welcoming activities include five minutes of freewriting and a word of the day. The video below ends with students’ anecdotal statements about their emotional and psychological assurance from the GWMP (see Appendix C for its transcript).

Additionally, allocated space may be the most important factor in such a writing program for cultivating a comforting and welcoming environment that increases students’ ability to focus and write. Through the stages of the GWMP, it became clear that space, physical or virtual, is a vital component in these groups. The virtual space that is shared on a Zoom session is vastly different from one in a designated room on campus, but they both encourage graduate students to focus on writing, share knowledge, and motivate each other (Remmes Martin & Ko, 2011). The following may be considered in creating a physical space: room temperature, enough space for each student’s books and materials, conferences needing extra space, soundproofing, location, and budget for possible snacks and refreshments. A virtual space might include greetings and a welcoming atmosphere, logistic flows and conflicts, virtual background, and technical support. The current GWMP, as a regular routine of weekly activity, creates a peer-like community and space between consultants and tutees and among tutees.

The first two stages, in particular their logistic data and feedback from the students and consultants, informed the growth and evolution of the GWMP. An addition to the early structures was appropriate accountability. Currently, the GWMP consists of a fully online format using Zoom with an application-based cohort and a waiting list. Attendance is mandatory to retain a spot in the program as are one-on-one breakout sessions, which are used for setting goals. Most GWMP students in the current cohorts expressed at times how they enjoy that this program is every week for a set period of time and that the consultant is there to keep them motivated and accountable for the goals they set for themselves. Students are also held accountable by their peers who rely on the group for shared information, knowledge, encouragement, and other emotional support (Brooks-Gillies et al, 2020). Additionally, accountability also refers to the program itself. The success of this writing program did not happen immediately or in the first trial; it took time to contextualize the program to maximize meeting students’ needs and boosting students’ academic and professional success. Such a process needs support in personnel, budget, and assessment to reflect the potential positive outcomes.

Finally, the outcome of this program has been progressive reciprocity. One significant impact of this program has been seen on graduate students’ “retention, learning, and the social and emotional development” (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012, p. 73). Keeping track of the progress of the writing group participants and asking participants’ feedback is necessary to evaluate the effectiveness and popularity of the program both in the short term and the long term (see Appendix A for some questions in the exit survey). In addition to its outcomes and evaluations, the statements of GWMP students’ and consultants’ take-aways over the horizontal process would add a rich description of peer learning and peer collaboration (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012).

Conclusion

With growth, adaptability, and evolution, the GWMP has grown into a successful program which serves graduate students by breaking down final goals into small manageable goals every week, having graduate consultants mentor them and arranging learning or writing partners to write on, and by establishing a community to share thoughts, feelings, strategies, and vulnerabilities. The GWMP, like successful programs of writing groups in other universities, provides a clearer pathway for graduate students to continue their academic journey and become their own motivators. This way, they are able to meet their goals of graduating on time. The success of the current GWMP is attributed to multitudinous collaborations, allocated space, appropriate accountability, and progressive reciprocity. As the result, the authors have proposed them as several considerations for best practices in other WCs. The authors welcome readers’ feedback and collaborative efforts to move forward with an empirical study that would provide “a common language to reach external audiences” and “legitimize” WC practice (Driscoll & Powell, 2015, para. 1).

References

Bell, K. & Hewerdine, J. (2016). Creating a community of learners: Affinity groups and informal graduate writing support. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 50–55. http://www.praxisuwc.com/141-final

Bitzel, A. (2013). Who are “we”? Examining identity using the Multiple Dimensions of Identity model. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 11(1), 1–6. http://www.praxisuwc.com/journalpage111

Brooks-Gillies, M., Garcia, E. G., & Manthey, K. (2020). Making do by making space: Multidisciplinary graduate writing. In M. Brooks-Gillies, E. G. Garcia, S. H. Kim, K. Manthey, & T. G. Smith (Eds.), Graduate writing across the disciplines: Identifying, teaching, and supporting (pp. 191–209). The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/ATD-B.2020.0407.2.08

Costello, K. M. (2018). From combat zones to contact zones: The value of listening in writing center administration. The Peer Review, 2(1). http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/relationality-si/from-combat-zones-to-contact-zones-the-value-of-listening-in-writing-center-administration/

Driscoll, D. L., & Powell, R. (2015). Conducting and composing RAD research in the writing center: A guide for new authors. The Peer Review, 1. http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-0/conducting-and-composing-rad-research-in-the-writing-center-a-guide-for-new-authors/

Flores-Scott, E. M., & Nerad, M. (2012). Peers in doctoral education: Unrecognized learning partners. New Directions for Higher Education, 2012(157), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20007

Harris, M. (1982). Growing pains: The coming of age of writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 2(1), 1–8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441754?seq=1

Kells, M. H. (2016). Writing across communities and the writing center as cultural ecotone: Language diversity, civic engagement, and graduate student leadership. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 27–33. http://www.praxisuwc.com/141-final

Making the Case for Your Research: Four Novelty Moves. (n.d.). Student Academic Success Center. Retrieved September 11, 2021, from https://www.cmu.edu/student-success/other-resources/handouts/comm-supp-pdfs/establish-novelty-four-moves.pdf

Mannon, B. O. (2016). What do graduate students want from the writing center? Tutoring practices to support dissertations and thesis writers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 59–64. http://www.praxisuwc.com/new-page-29-1

McBride, M., Edwards, B., Kutner, S., & Thoms, A. (2018). Responding to the whole person: Using empathic listening and responding in the writing center. The Peer Review, 2(2). http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-2/responding-to-the-whole-person-using-empathic-listening-and-responding-in-the-writing-center/

Reineke, J., Glavan, M., Phillips, D., & Wolfe, J. (2018). Novelty moves: Training tutors to engage with technical content. In S. Lawrence & T. M. Zawacki (Eds.), Re/Writing the center: Approaches to supporting graduate students in the writing center (pp. 163–181). Utah State University Press.

Remmes Martin, K., & Ko, L. K. (2011). Thoughts on being productive during a graduate program: The process and benefits of a peer working group. Health Promotion Practice, 12(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910383687

Rollins, A. (2015). Equity and ability: Metaphors of inclusion in writing center promotion. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1), 3–4. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/62623

Whitcomb, A. (2016). “I cannot find words”: A case study to illustrate the intersection of writing support, scholarship, and academic socialization. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 87–93. http://www.praxisuwc.com/141-final

Appendix A

GWMP Exit Survey in Spring 2020

- What are your writing goals in quantity during each session?

a. below 3 pages

b. 3-5 pages

c. 6-8 pages

d. above 8 pages - How much of your writing goals do you usually achieve during each session?

a. below 50%

b. 50-70%

c. 71-90%

d. Above 90% - Which area do you mostly need mentors’ support? You may choose more than one.

a. Literature review

b. Formatting

c. Grammar and sentence structure

d. Organization

e. Time management

f. Stress and anxiety

g. Communication with committees/advisors

h. Other___________________________ - Was the support provided sufficient?

a. Yes

b. Maybe

c. No - Which part of the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program do you find most useful? You can choose more than one.

a. More knowledge in what to write

b. More knowledge in how to write

c. More confidence in writing on and writing up

d. More self-regulation to motivate myself in writing

e. More confidence in graduating (on time)

f. More awareness of writing resources from the institute and online

g. Less anxiety about deadlines

h. Less anxiety to share my writing with others

i. Less nervousness to talk about my writing with peers and mentors

j. Others ___________________________

Why? ________________________ - Which part of the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program do you find least useful? Why? _______________________________________________

- How can we improve the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program? _______________________________________________

- On a scale of 1-5, how satisfied (i.e., 5) or dissatisfied (i.e., 1) are you with the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program?

5 extremely satisfied

4 somewhat satisfied

3 neither satisfied or dissatisfied

2 somewhat dissatisfied

1 extremely dissatisfied - Would you be interested in the Graduate Writing Mentorship Program in the next semester? Why? _______________________________________________

- When do you expect to graduate? _________________________________

Appendix B

Notes from the One-on-One Sessions

| Graduate Writing Mentorship Program Notes (Thursdays) | |

|

Student 1 |

The student had a question about citing indirect sources. I showed them the Purdue OWL and a specific resource about citing indirect sources. They’ve been keeping up with three pages a day, and they will continue onto next week. Their goal is to reach 15 single-spaced pages. |

|

Student 2 |

The student was able to submit their proposal for a conference. They are looking to repurposing that into a journal article. They want to start working on their PhD applications. I advised them how to get started, and how to approach the application process. |

|

Student 3 |

They have started their situational analysis, but they wanted to go over the writing more in-depth. I suggested making an appointment with the writing center so they can have more one-on-one attention. |

Appendix C

Transcript—Multitudinous Collaborations Video

Key:

S1 = Speaker 1

[ ] = Transcriber Notes

S1 00:00 — When it comes to collaborating with students, it’s important to keep in mind that

they’re actually working on a long-term writing project that has many different parts and many different emotions attached to it as well. So, the act of collaborating with one another and creating a space of inclusion allows these graduate students to have an awareness with those who are also working on various writing projects like dissertations, grant proposals, theses, etc.

S1 00:28 — By collaborating with one another, a writing group becomes a space for creating a

community of support. In “Making Do by Making Space,” Brooks-Gillies et al. (2020) discuss a research study on writing groups where one student commented how they “liked that it felt like there was no judgment about [their] character as a graduate student. It was accepted that you’re a doctoral student, you’re trying to get somewhere, and we’re trying to help you with your writing and trying to make it better. That’s all the focus was on and [they] really liked that that was it. There was no other stuff brought into the room” (p. 198).

S1 01:01 — In a similar way, a current student in the current Graduate Writing Mentorship

Program expressed how they are appreciative of the fact that the university created this group for students like them. They feel that they’re not alone and they feel that they’re in the same boat as everyone else in the group. Collectively, students also find that the atmosphere is a welcoming one where they feel free to discuss their writing progress. [END OF VIDEO]