Kelin Hull, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Cory Pettit, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis

Abstract

Amidst the jarring backdrop of spring 2020, we asked ourselves how, after years of attention to the making of our writing center community, would we not only embark upon the labor of a suddenly online writing center, but continue to make one another matter (Gellar et al., 2007, p. 8)? Writing centers are messy because they are a confluence of overlapping boundaries, identities, and relationships (Brooks-Gillies, 2018, Gellar et al., 2007, Dixon, 2017), as well as sites of persistent and necessary emotion work that create place alongside the space (Boquet, 2002, p. 4). Therefore, our relationships between one another make and shape reality (Wilson, 2008, p. 7). This makes writing center communities central to writing center labor, but also underscores the excessive (Boquet, 1999, p. 478) complexity and nuanced nature of our communities. Using Jackson and McKinney as inspiration to consider how Discord allows us to “view the writing center from a different angle,” (2011) we consider how digital communities are constructed and intervene in writing center practice, especially during times of upheaval. This article focuses on five main concepts that emerged for us as we shared our experiences with Discord with one another: Space and Place, Embodiment and Relationships, Power and Power Dynamics, Signs and Symbols, and Stories and Archives. We will use these concepts to illustrate how having a writing center Discord server enabled us to negotiate both rosy and messy interactions during the fall 2020 and spring 2021 semesters, when our university was still predominantly online and our writing center was fully online. We will highlight the ways these interactions worked to (re)make community, offer some experiences that foreground the drawbacks of the server, and share insights into starting a Discord server.

Keywords: community, online writing centers, Discord, digital spaces, digital community, COVID-19, emotional labor

Making Community through the Utilization of Discord in a (Suddenly) Online Writing Center

Amidst the jarring backdrop of spring 2020, we asked ourselves how, after years of attention to the making of our writing center community, would we not only embark upon the labor of a suddenly online writing center, but continue to make one another matter (Gellar et al., 2007, p. 8)? What would happen as we could no longer share space in our Center, in hallways, around tables, and other campus places we had come to recognize as integral to our community’s sustainability? How would staff meetings operate, let alone feel, when we could not share food, hand each other written notes (known as Huzzahs in our writing center), and take silly photos? How would it feel to be in a session without the buzz of conversation whirling around us or without the ability to lean over and ask a colleague a quick question? Writing center professionals often lean on the idea of community when talking about our writing centers and our relationships with one another (Boquet, 2002), painting a picture that is uncomplicated and rosy (Dixon, 2017); a place where potlucks and coffee pots bind us together, creating a safe and accessible story of community because it feels good (Gellar et al., 2007, Bouquet, 2002, McKinney, 2013). In recent years we have begun to break open this story, leaning into the messiness of our communities because we now understand the meaning-making such messes provide (Dixon, 2017). Writing centers are a confluence of overlapping boundaries, identities, and relationships (Brooks-Gillies, 2018, Gellar et al., 2007, Dixon, 2017), and are sites of persistent and necessary emotion work that create place alongside the space (Boquet, 2002, p. 4) where our relationships between one another make and shape reality (Wilson, 2008, p. 7). This makes writing center communities central to writing center labor, but also underscores the excessive (Boquet, 1999, p. 478) complexity and nuanced nature of our communities. In short, writing centers require communities, but communities require consistent care, attention, and hard labor to build and maintain.

For our writing center, which consists of undergraduate and graduate peer consultants[1] , community is built into the structure through systems and practices. We orient our community around a central mission statement that “requires respecting and valuing the unique cultural and personal histories, knowledge, and language practices each writer brings into their writing” (Our Mission). All consultants become eligible to work in the Center after completion of a 3-credit course with a strong emphasis in cultural rhetorics, social justice, and decolonial theory and pedagogy. Once hired, consultants are paired with an experienced consultant mentor and, in addition to consulting and other job-related tasks, learn to participate in one of four committees, Language and Cultural Diversity across Campus (LCDAC), Social Media (SM), Research and Assessment (R&A), and Online and Communication Resources (OCR). These committees each have a peer coordinator that is part of our Leadership Team (LT) and have a mixture of core and additional projects that support the work and mission of the Center, both through professional development and through community collaboration. This work is reinforced and utilized in bi-weekly staff meetings, which are a mixture of informal gathering time, official programming, and committee time. The structure of our Center, the decolonial mission of our Center, and the continued emphasis on professional development and collaboration helps make and sustain the community of the Center.

After the onset of the shelter-in-place orders and shifts to online course delivery, however, our carefully tended community felt as if it was retreating into the dislocated boxes of Zoom. We placed emphasis on communication: student shift leaders[2] and the Director and Assistant Director held open office hours that even had fun names in Zoom. We used Canvas to try to encourage interaction in discussion boards and loaded necessary and new information into modules for consultants to reference. Our weekly email newsletter to staff became more frequent and focused on things like self-care and sharing contact information for resources. We gathered as a full staff for Zoom staff meetings, trying to smile and wave and chit chat and even craft silly things with one another, but in reality, we weren’t with. We couldn’t simply recreate the same community-building interactions we had at in-person staff meetings and expect the same results. It wasn’t enough; none of us felt connected. Everything, from Huzzahs to the kinds of professional development programming we facilitated would need to be reconsidered. We could no longer share space with one another; what we did share was our sense of dislocation and isolation, taking an extreme toll on our mental health. Outside of the pandemic, the world felt aflame–racism and racial violence, the election and its aftermath, environmental disasters, financial upheaval and instability—and we, completely displaced from any recognizable notion of our community, felt it slipping through the fingers of all of these digital platforms designed to hold us together.

As the spring semester drew to a close and summer plans were upended in university-level financial decisions that caused our writing center to remain closed, an undergraduate consultant, Cory, suggested we start a Discord server for our staff. Kelin, the Assistant Director, in conjunction with our writing center’s Director, saw that the server would centralize communication about writing center work. We were less sure about how it would impact our community slippage but hoped it would become a space that would allow for the “everyday exchanges” (Gellar et al., 2007, p. 6) we lost in the online upheaval. Using Jackson and McKinney as inspiration to consider how Discord allows us to “view the writing center from a different angle” (2011) in this article, we consider how digital communities are constructed and intervene in writing center practice, especially during times of uncertainty. This article will focus on five main concepts that emerged for us as we shared our stories and experiences with Discord with one another: Space and Place, Embodiment and Relationships, Power and Power Dynamics, Signs and Symbols, and Stories and Archives. We will use these concepts to illustrate how having a writing center Discord server enabled us to negotiate both rosy and messy interactions during the fall 2020 and spring 2021 semesters, when our university was still predominantly online and our writing center was fully online. We will highlight the ways these interactions worked to (re)make community and offer some experiences that foreground the drawbacks of the server. Lastly, we will forecast how Discord might become integrated into the practices of our writing center beyond the pandemic and share some guidance on starting a Discord server.

An Overview of Discord

Discord began life in 2015 as a gaming-focused alternative to platforms such as TeamSpeak and Skype, which were oft-used but not well-liked solutions for voice chatting in gaming communities. The platform also offered text-based channels for communicating while not in a voice call, similar to Slack. Discord’s initial popularity came as a result of the combination of these two functions, with Discord’s voice chat functionality receiving a great deal of development and honing to the point where it achieved a status far superior to the other options communities had at their disposal. While the platform has always been used for communities focused around things other than gaming, with as many as 30% of servers surrounding unrelated topics since the early days of the service, COVID sped up Discord’s transformation from a gaming-centered platform to a community-centered platform. It provided a sort of digital representation of the third place, something between the ideas of home and workplace (Pierce, 2020), which is a fitting description for it in the context of our writing center. Our Discord server is just that for many consultants: a complex mix of workplace and lounge, where consultants are free to come and go as they please, leaving messages for others to read later or participating in a synchronous conversation. Very often, participation comes down to leaving an emote or emoji reaction attached to a message, showing support for an individual, or expressing laughter or sadness, for instance.

While Discord does have the aforementioned screen sharing and webcam functionality integrated into its voice channels, the vast majority of communication on the platform takes place via messages sent in text channels. These text channels are organized into categories, typically, which allows server administrators to communicate a clear purpose for each set of channels. Both channels and categories can have an individual set of permissions applied to them; for example, anyone who joins our Discord server will see only two of our 46 text and voice channels until they are given a role which enables them to see the set of text and voice channels available to that role. These roles serve sometimes as a marker of hierarchy, such as our roles of Director and Assistant Director, while at other times as a function of visibility, such as the role that shift leaders have, which is intended to make obvious to consultants who is available to answer questions or handle any concerns which need to be addressed during a shift.

Experiences in Making Community in Discord

Unsurprisingly, when our writing center moved to online programming in response to the onset of the pandemic in spring 2020[3] , Kelin and the Director were unable to make time that was purely focused on administrative labor without also including time spent, in so many words, freaking out. As WCAs, Kelin and the Director had to “function as programmatic crisis responders who must act before, during, and after a crisis on behalf of the larger institution” (Clinnin, 2020, p. 132), for the writing center, and for the people within it. The emotional and relational were woven among the more obvious details vying for our time, energy, and attention, pushing the need for community to the forefront. Community, write Powell and Bratta, “is not a state to be achieved, but a process of making, a practice that is always intersectional, negotiated, nuanced, and changing; a practice that can’t be taken for granted” (2016). In spring of 2020, community became impossible to take “for granted.” Removed from physical proximity and spaces, the question of community became one of the most pressing administrative concerns for our writing center. While community has often been positioned as something outside of the purview of more professional writing center work, much recent scholarship has been devoted to the topic of how much more is contained within our work: the invisible, relational, and emotional aspects of it that are “beyond [emphasis added] the center’s physical space” (Jackson and McKinney, 2011) and standard notions of one-to-one consulting. Because community is made through relations and emotions, we view community as a clear focus that is emerging for writing centers.

After trial and error with several platforms available for social networking and connection in the past, our experiences with Discord over the last year have told us a story that centralizes relationships through incidental interactions and supports and makes visible the shared emotion work that continuously makes and remakes our community during the pandemic. Not unlike a physical writing center, Discord fosters connection and communication alongside occasional disagreements and miscommunications. We therefore see Discord as a digital manifestation of Boquet’s call for seeing writing centers as a “liminal zone where chaos and order coexist” (Boquet, 2002, p. 84). The stories we share here center the continued necessity and messiness of writing center communities and labor and highlight the ways in which Discord is similar and different to physical spaces in supporting the work of community making.

Space and Place

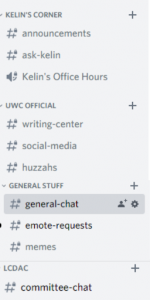

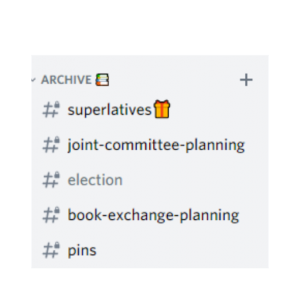

At first glance, Discord seems to be well-ordered. Each channel in our server has its own hashtag by its name, with its own permissions and notifications, like a map with clear boundaries and borders, resonant with Jason Farman’s call to map digital spaces to make them visible “as a lived social space experienced in a situated and embodied way” (2012, p. 85). When we first set up the server, we tried to consider what kinds of labor happen in a writing center that would need to be made visible, bound, and mapped, with each category of that labor its own labeled and navigable location. Indeed, at first glance of the sampling of our server’s channels featured in Figure 1, it might even appear as if we succeeded.

There is a #general-chat channel and its professional counterpart, the #writing-center channel. There are channels for shift leaders (#office-hours-chat) and for administrators (#ask-kelin). Each committee has its own channel to connect around projects. Yet, as we experience and use Discord, it has quickly become apparent that not all channels are stable, nor are they necessarily discrete, with many channels evolving over time or new channels springing to life only to be archived in a few weeks. This highlights the “frontier” aspect of digital spaces, where users can reconstruct “freely to fit their particular needs” (Farman, 2012, p. 85), making digital spaces unstable and difficult to map in a traditional sense.

Space is negotiated through how the bodies within use it, whether physical or digital. According to De Certeau, a space considers variables such as time and is “composed of intersections of mobile elements” so that “space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function” (1984, p. 117), making Discord a space that is in constant flux. For example, in the fall 2020 semester, we had an #election channel that enabled us to connect over news articles, speeches, debates, and eventually, the polls. In the final weeks of October and early November, the #election channel generated 1,471 messages in just 16 days’ time. However, its utility expired when the moment of its use had passed, and the channel soon became archived. Additionally, a conversation that begins in one channel inevitably spills over into others, not unlike the buzz and noise of our physical writing center locations where what happens at one table eventually makes its way around the room in conversations that range from debriefing over challenging sessions to inside jokes.

Indeed, while Discord remains a digital space, and is therefore limited in the kinds of interactions it can support, we have nonetheless been pleasantly surprised by the variety and depth of our Discord community. Our physical locations are spread across two spaces on a large campus and the administrative offices for the Assistant Director and Director are not near either location. Getting quick support and answers from the entire community is almost impossible. Discord, however, has condensed into one digital space what used to cross different writing center locations and campus places, like a big digital hallway filled with labeled doors. We each can walk in one door and find a group of people discussing food, some of them cooking or eating, and then across the hall, walk-in another door and find a group of people discussing citation styles. And yet, once in a room, we are not only in that room. We can bounce between channels in seemingly limitless abandon. Discord offers notifications with a variety of setting choices to help us navigate between channels and conversations. Discord’s affordances of space are reflexive and responsive to the changing needs of our community in ways our physical spaces are not. Rather than considering Discord a visual map of the kinds of labor a writing center requires, we consider it a way to encapsulate and experience the inherently relational nature of our work—how the work constitutes and shapes our relationships with one another and to the Center.

Embodiment and Relationships

Our bodies are rooted in a place that is isolated from the community, while at the same time experiences taking place in Discord have real effect and affect on us. To Wysocki, our bodies are our “primary medium” (2012, p. 3). They “are not fixed” (2012, p. 4) but are instead “always already embedded—embodied—in mediation” (2012, p. 4). Writing, then, is a “technology that enables us to experience our bodies as our bodies while at the same time mediat[ing] those bodies” (2012, p. 22). We are moved (in the Aristotelian sense) by what takes place in Discord, helping us generate and sustain emotional connections, even as we are in possession of less context about the other bodies we are in relation to. While our bodies are “embedded” and mediated within Discord, the dislocation of material reality and bodily affect can sometimes make interactions in Discord messy and complicated. Wysocki and Johnson-Eilola write about digital literacies as “between places” where space and time are “collapsing into one another” (1999, p. 363) and are being made and changed through “constructed relations” (1999, p. 365). Bodies exist in space and time, forming relationships and eventually communities through the everyday uses and practices the bodies undertake together, whether they exist in third spaces like Discord or in physical spaces.

Our bodies, as Micciche says, are already “in the room” (2007, p. 19), despite the room’s physicality and materiality suddenly vanishing. Like Michelle Gibson et al., we recognize “the narratives told about social institutions are embedded in or with the narratives of individuals” (2000, p. 72), so that “relationships with and among” our community are central to “the everyday work of the Center” wherein those relationships “are informed by institutional status, disciplinary credentials, lived experiences in and outside of the writing center, social identities, material and embodied realities, and emotion (Hull & Brooks-Gillies, in press). Our identities—all of our identities—and their attached emotions and contexts are in our bodies and so are in play in our interactions in Discord. For example, in an interaction in #ask-kelin meant to address a consultant’s concerns about supporting a particular citation style quickly, Kelin typed “Purdue Owl,” only to soon be corrected by the Director (“Purdue OWL”). Being corrected in a public way felt bad because Kelin was already not feeling well, and her capacity felt limited. However, the Director did not know Kelin was not feeling well—there are no bodily cues such as pale complexion, body posture, or even dress, to use in a text channel—and Kelin had not disclosed that she was not feeling well in writing. We are missing context and situation in most of our Discord interactions unless they get directly communicated, meaning that while our bodies are implicated in Discord, it is hard for us to fully reconstruct the bodies of others.

Just because our bodies do not share the same physical space does not mean they are divorced from the places where they currently are, no matter how different those might be for each of us. Our spaces still press on and influence our bodies in meaningful ways. For example, every semester the LCDAC committee hosts Difficult Conversations, which is a three-to-four part series open to the entire campus organized around a particular reading or topic meant to engage participants in conversations surrounding concerns of social justice. To reinforce this event, the entire staff is tasked with reading a few chapters of the selected text and discussing it together at a staff meeting. To support this work, we created a channel with the name of the text. In fall, it was April Baker-Bell’s Black Linguistic Justice and so we had a #linguistic-justice channel. In spring, we read Asao B. Inoue’s Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies and so renamed the channel #antiracist-writing-assessment-ecologies. While these channels are connected to the larger mission and overall committee structure of the Center, the interactions that take place in these channels are considered in their orientation to bodies, especially members of staff whose bodies may be marked or othered. Using the digital affordances of Discord to be intentional in our orientations to bodies does help us attend to them and to bring bodies more clearly into certain interactions.

While messy interactions and even conflicts occur, we believe that creating channels purposed to bodies has helped us foster a more conscious attitude towards bodies in our server. For example, a consultant recently experienced an emotionally difficult session with a writer. During the session, she was able to communicate her experiences in #writing-center and find immediate encouragement and resources to share with the writer, with consultants using gifs and memes, emotes, pinned messages, and supportive words. After the session, she was able to debrief about this experience with the community in #general-chat, adding context to her own difficult emotions and finding support. The shift leader and the Assistant Director offered to debrief in a voice channel with the consultant, and then finally the Assistant Director offered some resources in the #self-care channel. This sequence gradually narrowed the focus from managing the situation in a professional capacity to care and attention to the consultant’s embodied experiences in the challenging session.

In addition, since spring of 2020, we have introduced 7 new consultants into our community, people whom none of us have actually had the pleasure to meet “in-person.” At a recent meeting discussing the promotion of two new committee coordinators, one of whom is one of these newer consultants introduced during the pandemic, many of us remarked that it seemed odd that we hadn’t actually met. We felt like we had done so because of the quality of our interactions in Discord. New consultants can meet with experienced mentor consultants in voice and video chat channels. They can participate in low-stakes, fun channels such as #food, #pets, and #music-and-culture, allowing them ways to interact with the community outside of conversations about consulting. New consultants are able to make room for themselves in our community because of Discord. Indeed, these more positive examples are some of many we could have shared. For all of its potential messiness and its lack of embodied contexts, our experiences using Discord for relationship-building have been overwhelmingly positive. Discord remains consistent in its ability to provide nearly-synchronous written and fully-synchronous verbal and video interaction, which provides space for community-making that feels authentic and relational.

Power and Power Dynamics

As we pulled reports[4] from Discord to back-up our impressions of our experiences for this article, it became clear that we needed to question not just whether the body is in the room, but whose bodies are in the room. Who participates most? Who doesn’t? And what kind of power and/or social status is derived from that (non)participation? The reports reveal that there is high-level participation among members of the LT. This makes sense — LT members are also shift leaders, and therefore handle on-the-ground support issues during open hours in addition to their committee coordinator roles. However, we can divide participation between channels, and not all LT participation is limited to the so-called professional channels, such as #writing-center and #office-hours. Indeed, of the 71,314 messages sent since spring 2020, 53,355 have been sent by a member of the LT. This is analogous to the physical space, where committee coordinators run meetings, oversee committee projects, mentor new consultants, facilitate staff meeting programming, and carry the weight of reception duties. The size of the LT’s participation does not necessarily mean that others are not participating. As expected, everyone in our community has communicated and been present in Discord in some way, with one third being high-level participants, and two thirds being more intermittent. As in the physical space, participation in community is dependent on many factors such as time, level of comfort using digital spaces, position to and in the Center, level of investment in the Center, and individual identities. People should feel as if they can use Discord when they need support and community, but also not as if they have to. Although, as we examined these numbers, we became mindful that a lack of participation in Discord is something many consider to be cause for concern.

Participation in the physical space is inherent, with other things counting and showing as engagement. In Discord, however, all we have is presence—the green dot indicating we are online—and communications sent and/or reacted to. As we have seen in other stories we’ve shared, Discord does not allow for contexts, situations, and material realities of bodies outside of the digital space unless they are directly communicated in the server. Consulting, however, is embodied; in the physical space it is obvious, but in Discord it remains hidden. Consulting can be cross-referenced with a glance at WC Online, but it is not immediately apparent in the space of Discord, which is standing in for the physical space of the Center. In other words, the more obvious work of the writing center is not taking place in the community space of the writing center, and that creates tension between what counts as participation in the community. When we analyzed a log of all text communications sent by consultants in our Discord, we found that consultants doing a lot of consulting did not correlate to consultants doing a lot of participating in Discord. In addition, consultants may be meeting with one another or direct messaging one another to discuss projects but not talking about it in Discord, just as someone may be reading a lot of communications in Discord but not reacting or replying. We can reconstruct their participation ourselves, but this requires an extra step. Therefore, people participating less in Discord are seen as perhaps less involved in the community (which is opposite to the grand narrative of writing centers that privileges the one-on-one consulting aspect of the job).

Having access to statistics about Discord usage makes the divisions between engaged/not engaged more apparent. This is a good thing administratively—as the Assistant Director, Kelin has often drawn on Discord participation to consider who might need a “check in” and more administrative and emotional support. However, this can also exacerbate long-standing notions of community power dynamics, such as who has the most say in the forming of the community. In the physical space, consultants are often left alone without direct oversight for hours at a time. They are free to critique and express opinions that might contradict administrative decisions or administrative power without administrators knowing about it. This is not unwelcome but can be complicated in a physical space where, in our experience, such interactions can contribute to community instability[5] . Discord creates a community where open questions and critique of leadership decisions are easier and available to all, which we feel creates authenticity and transparency in our community, helping fuel our trust in another. However, it also reinforces the observational nature of Discord when Kelin or the Director may enter these interactions, which could hinder freedom of expression. Writing centers have historically been spaces of flattened hierarchies. The LT is an attempt to bring administration into relation with consultant voices and perspectives, and to provide all consultants the opportunity to make knowledge and community, thereby exercising power (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 43). However, because participation right now is limited by our use and perceptions of Discord, our hierarchy might not be as equitable and flat as we would like. Just as in a physical space, Discord is a space where whoever participates most gets more power in what the community does and how it behaves. However, because participation depends on activity instead of presence, participation is being marked.

Signs and Symbols

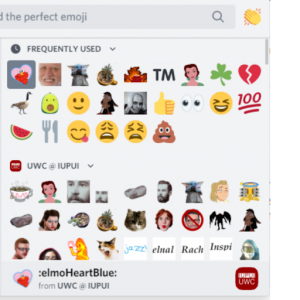

Aside from text communications in channels, the other participation that can be “read” in Discord is the use of reactions, which is also data that can be pulled from Discord for reference. Reactions exist as standard emojis similar to other social media platforms, and as emotes, which are custom. Custom emotes in our server have an agreed-upon community function and are born out of relational practice, most often requested in the #emote-request channel after a particularly memorable text communication exchange in another channel. There does not seem to be a relationship between people who send the most text communications in Discord versus people who react the most. There are different people participating at high levels through reactions. This is important to mark participation. We use De Certeau’s idea of names and signs as “imaginary meeting points,” that have been “detach[ed] from the places they were supposed to define” (1984, p. 104) to help us contextualize our experiences with reactions. According to De Certeau, reactions act as signs and/or symbols that signify what is “possible or credible,” what is “repeated or recalled,” and what is “structured,” in spaces (1984, p. 105). While we may have a rock or a picture of Foucault as an emote, which are pictured in our frequently used emojis and custom emotes in Figure 2, these emotes are only given meaning because they refer to something else, usually text that has come before.

In addition, by themselves they may stand-in for an inside joke or a story, but they are also given meaning by the text above it that they are reacting to. The text is written in relation to other texts produced by other people, sometimes nearly synchronously, and at other times, asynchronously. Emotes are then added by those not even writing the texts—they stand in place of a textual cue, or, what would be a bodily cue if we could physically see one another. In this way, emotes also help convey tone (in place of bodies) in writing, and so become integrated as structures into text communications. For example, when Kelin adds a smiley face emoji to the end of an announcement, or when consultants insert :hidethepain: into the middle of sentences to convey a grimace.

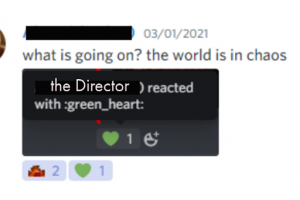

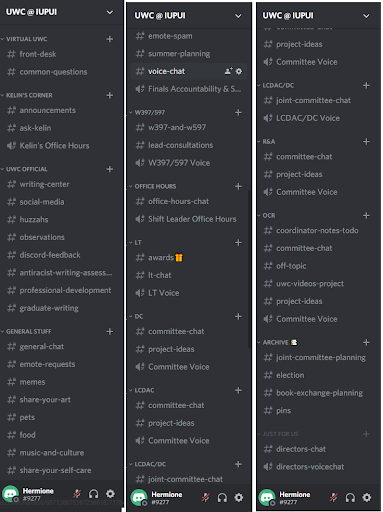

Emotes, then, are both signs and symbols in and of themselves, but also stand in for bodies in a digital space. This is why some of our more popular emotes are bodies. They are a way of marking a body’s presence in an interaction without participating directly, like smiling at someone or laughing at a comment across the room in a physical space. Indeed, certain reactions have become marked as a particular body. For example, Kelin’s favorite color is green, and so early in our use of Discord, she began using green hearts to react to text communications. Similarly, the Director’s favorite color is yellow and so uses a yellow heart. In one memorable interaction, the Director used a green heart to react to a written communication and the consultants immediately noticed, responding as pictured in Figure 3:

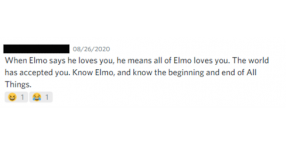

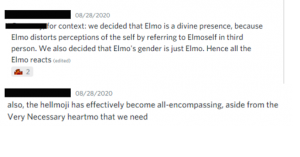

Other emotes are closely associated to the bodies of a particular consultant and are used to therefore mark that consultant’s body in response to a written communication or to refer to that body in a written communication, such as the :goose: emote, and earlier last spring, the :todd: emote, both of which referred to or were primarily used by a specific consultant in each instance. Reactions have evolved over time as we (re)make community through our interactions in Discord. One of our first custom emotes was the :elmoHeartBlue: pictured in Figure 2, that rose in popularity because it was clearly defined in a text communication by a consultant, as shown in Figure 4.

This made the :elmoHeartBlue: a “safe” emote to use as we negotiated meaning of reactions as a community. Occasionally a reaction will get used and a text communication exchange will have to clarify the reaction’s intent. An example of this occurred when Kelin used :hellmo: as a nod towards the popular “this is fire” phrasing as a reaction to a text communication by a consultant. The community had already defined :hellmo: as effective in this context (as outlined in Figure 5), but this consultant was not aware of this prior exchange.

The author of the text it was reacting to, however, did not understand and thought Kelin might be saying something like “hell no!” Similarly, after both Kelin and the Director added positive emojis to a difficult conversation taking place between consultants, a consultant communicated with Kelin in a direct message that he felt our positive emojis were approving of comments he was disagreeing with in the conversation. He perceived Kelin and the Director to be taking sides, which felt bad. Micciche draws on Ahmed to contend that emotions, such as the consultant’s mentioned in this example, “transform signs into ‘objects of feeling,” (Micciche, 2007, p. 28). If signs define spaces in structure, memory, and possibility, according to De Certeau, then Micciche highlights that these signs are also symbols that circulate emotion in and around the space, to both positive and potentially negative effect. Reactions, then, can become a way to validate and invalidate text communications, which can be tricky to negotiate, especially as we negotiate power dynamics and as certain emotes ebb and flow with community use.

Stories and Archives

The examples we have shared here to help theorize community in Discord are stories because “there is story in every line of theory” (Powell, 2012, p. 384). Stories are the way we communicate about our own lived experiences and cultures with one another. They are how we relate to one another. Emotes, text communications, links, and images shared in Discord are also all stories. We agree with Powell that “stories take place. Stories practice place into space. Stories produce habitable spaces” (2012, p. 391). Stories can be shared across time and space, whether first-hand or not. They are how we create a culture for our community. To Powell and to De Certeau, however, there is no measurable distinction between physical and digital space—the activity of sharing stories transforms anywhere into a space, because “space is a practiced place” (De Certeau, 1984, p. 117). While our bodies are in the room of Discord and our relationships may be helped or complicated by relations of power, it is the ability to share, repeat, review, and recall stories that makes Discord such a powerful engine for community-building. Discord acts as a cultural archive, collecting stories (like the ones shared in this article) in an accessible, efficient manner for years to come, creating a stable culture, deliberately crafted through the activity of its members. In our physical space, we have non-digital archives containing photos, blog posts, social media posts, staff meeting agendas, articles written and shared, and memories of experiences. They exist on a shelf, available to everyone who cares to read them. However, Discord is different in two ways: it is not curated, as is the archive in our physical space, and it is also a searchable archive. Discord is a space that collects everything that was said, indiscriminately. While we may wish to digitize our existing archives, and they will then be searchable, they will still be curated.

In considering participation levels and potential drawbacks to Discord, we both shared experiences of intensely personal and vulnerable exchanges taking place in #general-chat and other non-professional channels of the server. These exchanges range from community members losing jobs and housing, family illness and even death, all the way up to members feeling confused and frustrated about a particular professor or class. We stated earlier that channels come and go as the community uses them and moves on, just as conversations do in physical spaces. In Discord, however, conversations are not constrained to speech acts—they are in writing that exists in digital space and time, a third space that allows them to exist beyond the point of utterance. Things stay “in the room,” even if they have been archived[6], as in Figure 6.

We are concerned, therefore, that there are limits on the freedom of expression because the expression must be assumed for a wide audience unless it takes place in direct message. In addition, both Kelin and the Director are more present in Discord, observing and reading these incidental interactions. In the physical space, things could be said out loud and dismissed, forgotten, or kept secret in ways unavailable in Discord. These concerns bring the storied and archived nature of Discord to the forefront and begs us to consider, for example, questions of whether to delete certain kinds of posts from the server or how (and if) alumni should continue to have access to all, some, or none of the channels in the server even after graduation.

Finally, the reports we can pull from Discord are also stories, and allow us to quantify the previously invisible and undervalued interactions that work to make the writing center: the persistent emotional and relational labor. We see these reports as a way to “embrace the power of storytelling” to guide our pedagogical and theoretical approaches to writing center labor (Costello & Babb, 2020, p. 5) and a way to make the “often unrecognized and therefore unsupported” (Clinnin, 2020, p. 135) emotional labor of writing centers visible and archived. This could have potentially far-reaching implications for our writing center and for our discipline if more writing centers decide to host a server.

Emotions are subject to individual interpretation and experience but can also be a subject of community discussion and even tension. While everyone in our community undertakes emotional labor, not everyone practices and experiences emotional labor evenly because emotions are informed by our own experiences, identities, and relationships (Micciche 2007, p. 105). What one person might read as a barb or even a reprimand, others likely will not. What once was spoken to a select few on a shift and vanishing in time is now available to everyone in the community, perhaps permanently. Stories are not experienced in the same way across communities. The stories we choose to share, react to, highlight, archive, and even maybe delete, are determined by the institutional positions, the identities of the place, and the embodied experiences of the place in a digital space being remade through a daily rewriting.

Final Considerations

After two semesters of use, Discord has been and continues to be frequently praised and “Huzzahed” by consultants as a space dedicated to community making. Discord has afforded us a place to gather when no other places were an option, and together through shared practice we have made it a “habitable space” (Powell, 2012, p. 391). At its best, it allows us to interact informally in relation to each other, strengthening our professional community and fostering social connections in an otherwise isolated time. Because Discord is a space determined through relationships and use, however, it can also be a place of disorder and even conflict. This mess of interwoven relationships and identities is not unusual for a writing center, but the way in which Discord acts as an archive, recording the messy, emotional interactions of our day-to-day labors is unique. This storied lens of who we are together can centralize the focus of our community and our practice. It can foreground and normalize struggles and even frustrations with our work or with life. It can provide necessary emotional support and strengthen relationships. It can even make common concerns searchable. But it can also keep records of vulnerable information that may not be interpreted or used evenly as people enter and exit the community. It can both allow for greater critique and involvement in leadership and administrative decisions but its affordances for participation may engender instability between community roles and titles, creating a need for intentional and practiced narrative reinforcement by those with more power.

It is not new to consider the ways in which relationships and bodies are implicated in the construction of spaces and places, but it is a slight shift for many of us to consider the way in which digital spaces are constructed through bodies in relation. Community, write Ahmed and Fortier, is an effect of:

how we meet on the ground, as a ground that is material, but also virtual, real and imaginary. This ground that is ‘common’ is an effect of the meetings we have with others and the tread of feet that are weary across the land – a treading that shapes the land to come and allows it to surface differently (2003, p. 257).

In spite of its lack of physicality, Discord is common ground that roots us as a community to an imagined place. In the contact zone of the writing center, it is more than one-to-one sessions, but the constant negotiation of relationships and emotions among the bodies—all the bodies—contained within the space. Our bodies are present in the digital space, working to create community, what Ahmed and Fortier term the “effect of the very relations of proximity and distance between bodies” (2003, p. 255). In other words, the further away from the physical and material bonds of our relations with one another, the more pressing the question of our bodies and relations. Discord has become a digital community because of the “effect” of our “relations,” the movement of separate bodies experiencing shared emotions, even those that are complicated and messy.

As we considered how participation is marked, how our stories are told, reviewed, and archived, and how we use relationships to make community in this digital space, we consider again that community does not imply safety, similar experiences across identities, relationships, and contexts, or even consistent goodwill (Wenger et al., 2002, p. 144). Community, therefore, is “never fully achieved” and should be considered as something made through a “desire for” community, rather than as a space that “fulfills and ‘resolves’ a desire” (Ahmed and Fortier, 2003, p. 257, emphasis original). Over this past year, Discord has been a place of shelter, laughter, of shared frustration, outrage, and confusion, of trouble-shooting and resource-sharing, and of advice, support, and encouragement. Discord has sustained us and, in many ways, remade us as a community, as we all participate in varying ways, working to make the community together out of a deeply shared desire for it.

While the impetus to start a Discord server is attached to the global pandemic, we are mindful of the ways in which Discord has facilitated and eased communication and community collaboration. It is likely our writing center will be returning to the mixture of online and in-person consultations we offered prior to the global pandemic in fall 2021. However, we believe that our Discord server will remain an important, if not isolated, community resource even when some or all of us can share a physical space. Discord’s flexibility as a social and professional space make it particularly complimentary to writing center spaces, and is especially apt for writing centers that exist across multiple spaces. We also consider the ways in which Discord might serve as a site of disciplinary community across regional and even international writing center organizations that create their own servers. The use of Discord is now so interwoven into our community that, while use may shift, we do not foresee a time in the near future where it is no longer considered valuable by the members of our community.

Appendix A: Guidance on Starting a Writing Center Discord

While we believe every writing center will have its own approach to Discord (because Discord is made by the individuals within a community), we wanted to offer some guidance on how we introduced Discord to our community with the hopeful intent that it will prove useful to those interested in setting up their own writing center servers. We began Discord, as stated previously, based on the recommendation of Cory, the undergraduate committee coordinator for the OCR committee. The subject line of his email communication was “Maintaining Community Online via Discord,” which is remarkably similar to the title of this article. At the outset, Kelin and the Director had concerns as to whether participation in Discord would be required, whether it would confuse people to add (yet another) communication pathway to the mix, whether it would feel accessible to everyone, and whether this would complement, connect with, or maybe even replace certain practices we’d implemented hastily at the outset of the pandemic. Since participation was not required, then we could not guarantee engagement. What amount of labor would we spend setting up the Discord only to have it sit idle and unused? And what kind of engagement were we hoping for, exactly? None of this was certain, especially to Kelin and the Director, who had never even heard of Discord. We were wrapping up the spring 2020 semester and were exhausted and surrounded by institutional uncertainty that made us suspicious of trying something new that felt like it might be more work than we could support. Nevertheless, we decided to try it out first with just the LT on the practice server Cory had started. The initial setup of the server included a limited set of channels: #writing-center, #general-chat, and #ask-kelin. Once the LT began using it, it became clear that, while new to almost all of us, the functionality of Discord was relatable to existing platforms that made it approachable and easy to use.

After this trial period with the LT, we used limited hourly clock-ins over the summer (due to the financial constraints that prevented us from opening for consultations) to provide modeling language in Discord and to develop guides and materials for fall orientation when we introduced Discord. In the weeks leading up to the fall semester, we emailed the staff on how to accept Discord invitations, provided them an overview of the channels and their basic functions, and decided on how Discord would operate in an official capacity in place of the Zoom office hours that shift leaders and administrators had been holding during the spring 2020 semester. Cory developed an image-rich pdf walk-through of the invitation and login process. Cory then worked with his committee to develop an overview video that we could load into our fall Orientation Module in Canvas. We reinforced the image-rich texts, emails, and videos by dedicating time at our fall Orientation and our first staff meeting of the semester to questions and answers about Discord. Participation in the server was limited as the semester began, and many of the earliest messages were those sent by Cory in an effort to model how those less familiar with Discord would be able to use it in the coming months to build community and support each other professionally. Within the first three weeks of the semester, everyone on staff had logged-in to the server and 8,112 messages had already been sent.

Appendix B: A Full View of Every Channel in our Discord

Notes

- In spring 2020 we had 36 consultants. ↑

- Shift leaders are experienced consultants and normally consult during their shifts. However, in the move to a fully online writing center, we decided shift leaders should be available for communication and support at all times. We felt having shift leaders available was important to maintaining the community focused and collaborative consulting model we had built together in our physical space. ↑

- Understandably given the situation, and as with many other education institutions, we were given very short notice and uncertain timelines, which made planning and coordination particularly challenging. ↑

- Discord provides reports of all text communications in the server. It cannot track direct messages or voice/video chats. ↑

- More description about these experiences can be found in Kelin and the Director, Marilee Brooks-Gillies’ chapter entitled “Emotional and Embodied Relationality in Writing Center Administration: Attending to Institutional Status, In-Betweenness, and the (Re)Making of Community” in the forthcoming collection Affect and Emotion in the Writing Center edited by Janine Morris and Kelly Concannon. ↑

- As an administrator, Kelin can access all archived channel. ↑

References

Ahmed, S. & Fortier, A. M. (2003). Re-imagining communities. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(3), pp. 251-259.

Bouquet, E. (1999). ‘Our little secret’: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. CCC, 50(3), pp. 463-482.

Boquet, E. (2002). Noise from the writing center. Utah State University Press.

Brooks-Gillies, M. (2018). Constellations across cultural rhetorics and writing centers. Writing Centers and Relationality: Constellating Stories, special issue of The Peer Review.

Clinnin, K. (2020). And so I respond: The emotional labor of writing program administrators in crisis response, In C. A. Wooten, J. Babb, K. M. Costello, & K. Navickas (Eds.), The things we carry: Strategies for recognizing and negotiating emotional labor in writing program administration (pp. 129-144). Utah State University Press.

Costello, K. M. & Babb, J. (2020). Emotional labor, writing studies, and writing program administration, In C. A. Wooten, J. Babb, K. M. Costello, & K. Navickas (Eds.), The things we carry: Strategies for recognizing and negotiating emotional labor in writing program administration (pp. 3-16). Utah State University Press.

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Steven Rendall, translator. University of California Press.

Dixon, E. (2017). Uncomfortably queer: Everyday moments in the writing center. The Peer Review, 1(2).

Farman, J. (2012). Information cartography: visualizations of internet spatiality and information flows, In K.L. Arola & A. F. Wysocki (Eds.), Composing(media)=Composing(embodiment): Bodies, technologies, writing, the teaching of writing (pp. 85-95). Utah State University Press.

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., & Boquet, E. H. (2007). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Utah State University Press.

Gibson, M., Marinara, M., & Meem, D. (2000). Bi, butch, and bar dyke: Pedagogical performances of class, gender, and sexuality, CCC, 52(1), pp. 69-95.

Hull, K. & Brooks-Gillies, M. (In press). Emotional and embodied relationality in writing center administration: Attending to institutional status, in-betweenness, and the (re)making of community, In J. M. Morris & K. Concannon (Eds.), Affect and Emotion in the Writing Center.

Jackson, R. & McKinney, J. G.. (2011). Beyond tutoring: Mapping the invisible landscape of writing center work, Praxis, 9(1).

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Utah State University Press.

Micciche, L. R. (2007). Doing emotion: Rhetoric, writing, teaching. Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Our Mission. (n.d.). University Writing Center. Retrieved May 10th, 2021, from https://liberalarts.iupui.edu/programs/uwc/about-us/our-mission/

Pierce, D. (2020, October 29). How discord (somewhat accidentally) invented the future of the internet. Protocol. https://www.protocol.com/discord.

Powell, M. (2012). Stories take place: A performance in one act. College Composition and Communication, 64(2), pp. 383-406.

Powell, M. & Bratta, P. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: Entering the cultural rhetorics conversations. Enculturation, 21.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Harvard Business School Press.

Wysocki, A. & Johnson-Eilola, J. (1999). Blinded by the letter: Why are we using literacy as a metaphor for everything else, In G.E Hawisher & C.L. Selfe (Eds.), Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies (pp. 349-368). Utah State University Press.

Wysocki, A. F. (2012). Introduction: Into between—On composition in mediation, In K. L. Arola & A. F. Wysocki (Eds.), Composing(media)=Composing(embodiment): Bodies, technologies, writing, the teaching of writing (pp. 1-24). Utah State University Press.