Jing Zhang, Shantou University

Abstract

While rich scholarship has delved into the lives, accomplishments, and struggles of writing centers, the closing, or “death” of writing centers has been largely underexplored. With a survey and a focus group, this study examines students’ perceptions of and reaction to the closing of a satellite writing center on a regional campus of a Northeastern, mid-size, public research university in the United States. This study revealed: 1) the student participants not only viewed the satellite writing center as an important resource but also a community, 2) they expressed sadness and disappointment toward the writing center closing, maintaining that the writing support should be offered to students, and 3) after the writing center was closed, some of them utilized various alternative writing support, while others did not. By inquiring into the death of a writing center, this study enriches and complicates the writing center grand narrative that McKinney (2013) calls us to problematize. Furthermore, based on findings that revealed students’ writing-related help-seeking behaviors in response to dramatic changes, implications are offered to writing center professionals and educators who seek to cultivate students to become resourceful and resource-savvy writers, especially in a time of challenges and changes.

Keywords: Writing center closing, satellite writing center, writing center storying, writing resourcefulness

“It’s been a fun ride: Armstrong State University says farewell to the SWCA Annual Conference”

“Writing center closes due to lack of funding”

“The death of a ‘writing center’?”

“Farewell,” “close,” “death,” … these words are sad, final, and carry a sense of despair. When such words are associated with writing centers, they tell sorrowful stories that dishearten us writing center professionals. As a scholar dedicated to writing center work and research, I have not only heard about such stories but also lived one myself.

With my exciting experience of creating a writing center from scratch with my colleagues in China and directing it for three and a half years, I found it all the more difficult to witness the death of a satellite writing center in a United States university during my first doctoral year as a graduate assistant. Having worked at this small satellite writing center as the assistant director for a semester, I still remember how I felt when I first stepped into the cozy, colorful room that we called “writing center” on that small regional campus, which is about 33 miles from the main campus of a Northeastern, mid-size, public research university: I felt joy, excitement, and promise; I was ready to work closely with student writers, create new initiates, and make real changes within my anticipated two years there—the same kind of vitality and aspiration that I had when I created my writing center at a Chinese university four years ago.

However, I did not have all that much time to compose my chapter in the story of this writing center—my chapter came to an abrupt end in the middle of the academic year. Without much of a warning, the decision to close the satellite writing center was passed down and all of a sudden, I found myself helping my director take down posters and students’ works from the wall, packing books and tutoring records with huge, black plastic bags, and giving stationery away to students. We finished it within a few hours, so quickly that I couldn’t help asking myself: so, this is it? That’s how we ended the life of a writing center after it had served the campus for more than a decade? Had it served its purposes? What about our students? What are they going to do when they need help with their writing? My head was spinning. I didn’t know.

A winter break later, I started my new assignment working at the university writing center on the main campus, but those questions did not cease to bother me. In a quiet corner of my heart, I kept wondering about my closed satellite writing center and the students who I used to spend time with. I wanted to know, out of personal concern and curiosity, whether the disappearance of the writing center had any impact on the students and how they reacted to the loss of this long-existing campus resource; meanwhile, as a writing center scholar who found little literature on writing center closing, I wonder what knowledge we can gain by delving into the death of this small writing center to enrich our understanding of the lives of writing centers.

To me, the life story of my writing center was finished without an ending. To tell its full story and to make meaning that might speak to many other writing centers’ (untold) stories, I conducted an empirical study to probe into my most pressing question: how did the students on the regional campus perceive and react to the closing of the satellite writing center? With a qualitative design that consisted of an online survey and a focus group discussion, I obtained input from the academic students who the satellite writing center had served, striving to draft the final chapter of this writing center’s life through students’ voices. As such, the significance of my study is two-fold: 1) by investigating how students felt about and coped with the closing of a satellite writing center, I examine the impact of the writing center closing through students’ voices, and 2) unlike the more prevalent research that has looked into the vigorous life of writing centers, I seek to tell another side of writing center stories through an iconoclastic inquiry into the death of a writing center, which can enrich and complicate the writing center grand narrative, one that Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2013) calls us to problematize. Furthermore, based on my findings that revealed students’ help-seeking behaviors in response to dramatic changes, I offer implications to writing center professionals and educators who seek to cultivate students to become resourceful and resource-savvy writers, especially in a time of challenges and changes.

Closing of Writing Centers

Amid scholarship that documents and theorizes the lives of writing centers, the “deaths” of writing centers are largely underexplored, and research that specifically examines writing center closing is rare. With the bulk of our scholarship focusing on the development and improvement of writing center praxis, we tend to perpetuate the writing center grand narrative, which depicts writing centers as “comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-to-one tutoring on their writing” (McKinney, 2013, p. 3). However, if we honor this representation as if it were the solely true version of writing center story, we risk creating “a sort of collective tunnel vision” (McKinney, 2013, p. 5) that fails to capture the complexity and richness of writing center storying—writing centers do struggle, they get eliminated, and their closing is by no means inconsequential. Writing center closing deserves scholarly attention, because they are not only a phase of writing center life, but also a generative component of writing center storying. Thus, one promising research direction is to delve into how the closing of a writing center impacts the students it used to serve. As such, this study aims to contribute new insights to the writing center community through an investigation of students’ perceptions of and reaction to the closing of a writing center. To do so, I review extant literature on writing closing as follows.

Outside of traditional academic publication venues, brief reports of writing center closing have appeared on webpages, such as McDonald’s (2016) online article reporting on students’ and staff’s anger over the New Jersey City University’s plan to shut down their writing center, Spitzer-Hanks’ (2016) blog post about the shutdown of tutoring services at the University of British Columbia Writing Center, and Farley and Nealey’s (2017) report on the closing of the writing center at Savannah State University due to the lack of funding. However, all of these sources only report on the closings without in-depth discussion about their impact.

On the other hand, writing center scholarship, especially empirical research, rarely investigates the reasons, processes, and repercussions of writing center closing, except for bits and pieces that scatter over literature. For example, in her study that examines how writing centers are positioned in the political-educational climate in the United States, Salem (2014) mentions in her method section that with a sample of nearly 400 accredited institutions, “a number of institutions included in the original sample ultimately had to be dropped from the analysis. Some had closed or lost accreditation, and others had stopped offering baccalaureate degrees” (p. 21). This statement reveals that some writing centers closed due to the closing of their housing institution, which is only one reason for writing center closing. Similarly, Essid (2018) states that the integration of writing centers to learning commons has appeared to be a means to re-structure academic entities, while Reese (2017) suggests that the merging of universities has led a university writing center to become a satellite institution. However, little research appears to delve into the disappearance, closing, and “deaths” of writing centers, which calls for thorough inquiries into the impact and consequences of writing center closing.

An exception is Cirillo-McCarthy’s (2012) year-long comparative study of two writing centers through ethnographic and textographic methodologies: The University of Arizona Writing Center in the U.S. and London Metropolitan University’s Writing Center in the U.K. Cirillo-McCarthy (2012) discusses three crises that these two writing centers reacted to, including crisis of access, crisis of literacy, and crisis of funding. In particular, despite their director’s efforts of gaining support from international writing studies and writing center scholars through support letters, London Metropolitan University’s Writing Center was rendered in a reactive instead of proactive place and was finally eliminated due to the lack of funding. In contrast, although it was also faced with a funding cut, the University of Arizona’s Writing Center survived by reacting strategically, including finding a new home in a centralized student tutoring space and charging a nominal fee to all students. The struggles of these two writing centers portray a realistic picture of the various and mundane crises that writing centers face as well as the different fates of writing centers resulting from different reactions toward crises. In the case of the present study, the satellite writing center in question had also suffered from different crises prior to its closing: 1) it received little funding from the university (e.g., when activities such as a scavenger hunt was held at the satellite writing center, the director brought home-baked muffins rather than receiving financial support from the university), and 2) the drastic shrinkage of academic student enrolment on the regional campus—from several hundreds to around twenty five—called the necessity of the satellite writing center into questions and further threatened its already peripheral status, which all contributed to its final closing.

In short, because the limited literature on writing center closing are either brief reports on closing or studies that approach the issue from the administrator’s perspective rather than the student’s perspective, our knowledge about writing center closing is limited to the reasons for closing and the fight against closing—which tends to end with the closure itself. Therefore, by investigating the impact of writing center closing in a post-closure fashion and through students’ voices, the present study is the first of its kind. With a focus on how the students perceived and reacted to the closing of a satellite writing center, I aim to draw writing center scholars’ attention to and initiate much-needed conservations about writing center closing.

Methods

Research Site and Participants

The writing center in question was a satellite writing center on a small regional campus of a Northeastern, mid-size, public research university in the United States. Having served the students on the regional campus for more than a decade, this writing center provided one-on-one writing support in all phases of writing, including brainstorming, outlining, drafting, revising, proofreading, and editing. Besides the routine one-on-one tutorials, other featured activities were offered to involve students in writing-related events and promote a culture of writing. For instance, a pen-pal project was initiated at the beginning of fall 2017 to pair students on the regional campus with Chinese college students from a university in China, so that students could practice real-life writing through email exchanges while also enjoying cross-cultural experience and friendship. Meanwhile, a monthly Writers’ Meeting was held by the assistant director to gather students at the writing center to discuss their pen-pal experience and brainstorm potential contributions to the local newspaper. In addition, two posters were hung on the wall of the teaching building to invite students to write six-word memoirs and Thanksgiving notes with markers. The writing center was staffed with a graduate assistant (assistant director) and a professor (director), the latter of whom taught English composition classes on the regional campus; the director and assistant director worked as the only tutors at the satellite writing center.

During fall 2017, the writing center was open for six hours on Monday and three hours on Wednesday. The student body on this regional campus consisted mainly of two groups, academic students and culinary students, with the former group visiting the writing center more regularly. During that semester, only 25 academic students enrolled in the regional campus, and two of them dropped out mid-semester. A tight class schedule combined with a small enrolment resulted in a low visiting rate of the writing center, with only 23 tutorials in one semester (i.e., about 1.8 tutorials/week) and limited participation in the featured activities, which contributed partially to the closing of the writing center. The closing occurred in the middle of the 2017-2018 academic year; after the writing center was closed, composition classes were still offered to academic students on the regional campus.

Research Procedures

After obtaining IRB approval (Log No. 18-106) from my university in spring 2018, I administered an online survey and conducted a focus group interview to examine students’ perceptions of the writing center closing. Specifically, with the help of the administrative assistant on the regional campus, I distributed an anonymous Qualtrics survey to the remaining 23 academic students on the regional campus, to examine their usage of the writing center during fall 2017 and their perception of the writing center closing. Then, based on the preliminary findings of the survey, I developed a set of interview questions and recruited six participants for a focus group interview in two ways. First, with the help of the administrative assistant of the regional campus, I sent an email invitation to the academic students to recruit voluntary interviewees. Then, after two volunteers signed up for the focus group, two of them invited four friends of theirs, which demonstrated a snowball sampling method. All six participants were academic students who studied on the regional campus, with five female students and one male student. Although I did not intend to exclude non-users of the writing center, all the participants had experience using the satellite writing center during fall 2017 according to their self-report in the survey and the focus group.

Limitations

One limitation of this study stems from the fact that I assumed dual roles both as the researcher of this study and the former assistant director and tutor of the satellite writing center, which could affect the validity of my research findings, especially for the focus group where students might feel compelled to offer answers that please me due to my former role as their tutor. Therefore, I invited a fellow student from my doctoral program to help me lead the focus group discussion, while I took field notes. During the focus group, my participants responded mostly to my research assistant, with whom they had had no previous contact. As such, I weakened the impact of my previous role as the assistant director and tutor at the satellite writing center with the hope to elicit more candid responses. On the other hand, my past connection with the writing center provided me with a thorough understanding of my research context and participants, which gave me a unique lens to conduct this study. Additionally, because this study relied mainly on self-reporting data, I focused on students’ perceptions of the writing center closing without directly assessing the impact of writing center closing in terms of students’ writing performance, which is an interesting direction worthy of future research.

Data Collection and Analysis

Seven responses were collected through the Qualtrics survey, resulting in a 30% response rate. These responses accounted for the students’ participation in the satellite writing center during fall 2017, their perceptions of their writing center experience, their writing-related help-seeking behaviors, and their feelings about the closing of the satellite writing center (see Appendix A). The focus group discussion led by my research assistant was semi-structured, with a set of prompting questions along with spontaneous follow-up questions (see Appendix B). The focus group was videotaped and then transcribed.

Data were analyzed in two parts: 1) Participants’ answers to multiple choice questions in the survey were synthesized to present a big picture of the participants’ use of the writing center during fall 2017; 2) Participants’ answers to the open-ended questions in the survey and the transcript of the focus group discussion were coded through an open thematic analysis in NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software. Specifically, after reading the responses to the open-ended survey questions and the focus group transcript iteratively, I first conducted an exploratory thematic coding and assigned a list of codes and categories to capture the salient features of the responses; then, I performed Saldaña’s (2016) pattern coding to generate themes that grouped the codes and categories into patterns, which will be presented in the next section.

Results

In this section, based on participants’ survey responses and themes that emerged in my data analysis, I present the results of this study in four parts: 1) students’ self-reported participation in the writing center during fall 2017, 2) students’ perceived writing center experiences, 3) students’ perceptions of the writing center closing, and 4) students’ self-reported alternative writing support.

Students’ Participation in the Writing Center

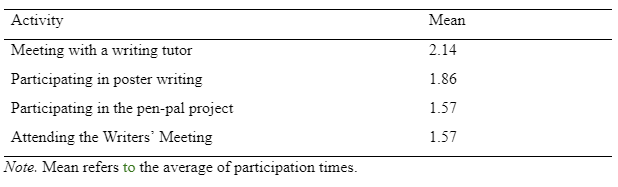

All seven survey respondents reported having used the writing center during fall 2017. In response to the survey question, “Which one(s) of the following writing center activities did you participate in and how many times?”, the seven responses are presented in Table 1. Among the seven participants, their most frequent contact with the writing center was consulting with a tutor about their writing, resulting in an average of 2.14 writing center visits during fall 2017. Even though 2.14 visits per semester does not seem too low of a frequency on average, it is worth noting that all the participants in the survey used the writing center, while the majority of those who did not take the survey were non-users of the writing center. In other words, the more active writing center users, who participated in this study, skewed the visiting frequency, while the actual average of tutorials that happened at the satellite writing center per week was only around 1.8 tutorials. In addition, participants reported writing on the posters 1.84 times, while participating 1.57 times in the pen-pal project and the Writers’ Meeting. These numbers show that tutorials—the most standard writing center service—was used most frequently by students. As featured activities, poster writing gained more participation perhaps because it was quick, easy, and anonymous, while the pen-pal project and the Writers’ Meeting were more demanding due to their interactive and time-consuming nature.

Students’ Writing Center Experiences

Both students’ responses to the survey and the focus group discussion reflected their positive experiences of having a physical writing center available on the regional campus. In response to the survey question, “Which activity/activities do you consider the most helpful? Why?”, the responses from the participants were coded thematically in NVivo and revealed that across the seven participants, five of them reported finding the experience of working with a tutor “helpful” because of the advantages of meeting “one-on-one,” “face-to-face,” “with direct feedback,” and the expertise of writing tutors. Two participants reported “liking” the pen-pal project and one reported enjoying meeting “other people who liked to write” during the Writers’ Meeting.

Similarly, the focus group participants reported beneficial experiences working with a tutor. For instance, Tom[1] talked about how working with a tutor helped him get an A on a paper “for the first time.” Others discussed the benefits of having a satellite writing center, including its convenience and the expertise of tutors. For example, Grace discussed an experience when she had a problem with her memoir, she simply “ran up” to the writing center to discuss her problem with a tutor, which helped her realize the convenience of having a writing center available on the regional campus. Likewise, both Katie and Laura said that it would have been “easier” to have a physical writing center compared with using the online writing center[2] , and Katie, in particular, voiced her preference to “having the writing center that would strictly for helping you with writing and having someone who knows what they are doing.” Thus, in the participants’ eyes, the writing center used to be a helpful tool associated with positive experiences.

Besides tutoring, another important aspect that the participants attributed to enjoying the satellite writing center was the featured activities, which offered them opportunities to connect with more people by forming new communities. For instance, Susan, Katie, and Grace all said that they enjoyed learning about others’ interesting culture and life through the pen-pal project: Susan talked about how this experience helped her realize that there was “a whole, like a big world out there.” Katie said that she appreciated the kindness of her pen-pal, who wrote to check on her after she did not reply for a while. Grace shared her back-and-forth conversations about political and cultural topics with her Chinese pen-pal and mentioned happily that her pen-pal invited her to visit the UK, where her pen-pal would start her master’s program soon. Similarly, an anonymous survey response mentioned the enjoyable experience of “meeting more people” by visiting the writing center. Although the survey responses and the focus group addressed two negative experiences including not receiving a reply from a pen-pal and low participation in the Writers’ Meeting, the excitement that the participants demonstrated revealed that they valued the featured activities offered by the writing center. This indicates that the satellite writing center was not only a tutoring service limited to providing writing support; rather, it also functioned as a social and cultural community where students built connections and explored cultures.

Students’ Perceptions of Writing Center Closing

To examine students’ perceptions of the writing center closing and their experiences without the writing center during spring 2018, two sets of data were analyzed: 1) participants’ responses to the survey question, “The Writing Center was closed at the end of fall 2017. How do you feel about it?” and 2) the transcript of the focus group.

Overall, participants reported that they perceived the writing center closing as sad, disappointing, and disadvantageous. Words such as “sad,” “saddened,” and “disappointed” appeared in six out of seven survey responses. The focus group participants also articulated that they missed having face-to-face help at the writing center, along with an anonymous survey response mentioning missing seeing one of the writing tutors.

Students’ disappointment in the writing center closing was understandably warranted by their voiced writing challenges and needs for writing support. During the focus group discussion, four participants articulated their perceived difficulties with writing. For instance, Susan stated that she was “not very good with revision” and tended to “just write and say I’m done,” which made it helpful for her to learn about “ways to improve” and include “different ideas and concepts” in her papers. Similarly, Tom and Laura also tended to “just write and don’t think about it anymore.” These habits of writing without revisions and reflections necessitated students’ desire to gain support from writing tutors. Another writing challenge addressed by Tom and Laura was procrastination, with which others agreed. When talking about these writing difficulties, Susan, Tom, and Laura all shared positive past experiences of getting help from a writing tutor, who provided them with feedback, guided them to revise, or helped them finish writing and overcome procrastination. For example, Laura talked about how a writing tutor helped her generate a reverse outline, which guided her to construct her paper by organizing the “random thoughts” that she had had thrown in her paper.

Furthermore, the loss of the writing center seemed to reflect a sense of marginalization that participants felt on the regional campus. For example, Tom emphasized several times about the lack of support on the regional campus: “well there’s just not very much support here in general and now we’re removing even more support.” Similarly, Katie talked about how she could not depend on professors for help with writing because “they have to leave” the regional campus soon after class. Although this sense of marginalization might have existed due to the physical location and limited resources of the regional campus, the participants’ input indicated that the closing of the satellite writing center might have exacerbated this sense of marginalization.

Interestingly, while some participants perceived the influence of the closing as minimal on themselves personally—they either currently lived near the main campus or would move to the main campus in the next semester—Allie and Tom expressed concerns about the potential negative impact on future students: “especially like new people that will be coming you know next year.” Except for one survey response that stated “understanding it being closed,” most participants claimed that the writing center should be offered to students on the regional campus as a resource, despite their recognition of the low usage rate. To summarize in Katies’ words: “I don’t think you should take it from the people who, like, do want to use it even there aren’t a lot of students.” Therefore, it can be seen that students seemed to have a common attitude: regardless of the actual usage of the writing center, the writing center, as a form of support, should be available to students on the regional campus. Now, with the writing center closed, how would students deal with the writing challenges they faced? The next section presents the alternative writing support that students reported using.

Students’ Self-reported Alternative Writing Support

Based on the survey responses, I first present the additional writing support that students reported using in fall 2017, that is, prior to the closing of the writing center; then, based on the focus group discussion, I present students’ self-reported alternative writing support in spring 2018, after the writing center closed.

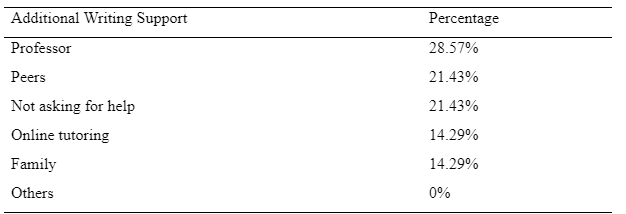

For the survey question, “Besides the Writing Center, where else did you obtain writing support during fall 2017?”, as Table 2 shows, the most frequently used writing support in addition to the writing center was from professors at 28.57%, followed by help from peers at 21.43%. Another 21.43%, namely by three participants, reported not asking for any support. The online tutoring service (offered by the university writing center on the main campus) and help from family were less often used, each at 14.29%, while no one checked the “Others” option. These percentages reflect that students mainly focused on support that was familiar or readily available to them within the academic context, such as help from professors and peers, while asking for less support that they were less familiar with or support from outside their immediate context (the regional campus), such as online tutoring and family. Additionally, three students reported not using any additional writing support, which means that the writing center was their sole writing support during fall 2017. Thus, the support from the satellite writing center was not only an important resource that students felt comfortable using, but also for some students, it was the only writing resource that they utilized.

The discussion in the focus group surrounding the interview question, “This semester, when you need help with writing, who do you turn to or where do you obtain help?”, revealed students’ use of alternative writing support after the writing center was closed. The participants described gaining writing support from their parents and the online writing center. For instance, Laura and Tom reported occasionally asking for help from their parents, while Susan and Laura had experiences using online tutoring offered by the university writing center on the main campus. Both Susan and Laura described their experience with online tutoring as “nice” and “helpful”. For example, Susan said, “I can hear her talking to me and it was nice hearing her like reading my paper back to me. I liked that experience so I could, like, listen to the flow of it and like the language.” Despite their positive experience using online tutoring, Susan and Laura both voiced their preference to working with a writing center tutor face to face, which echoes the anonymous responses in the survey that expressed appreciation for the face-to-face experience and direct feedback: “While there is an online writing center, I prefer to see someone in person and it’s more convient [sic] to me.” The others in the focus group had not had experience using the online writing center and Tom, in particular, “didn’t even know about the online thing.” The low participation in the online writing center and students’ preference to the physical satellite writing center reflect that although the online writing center was an available writing resource for all students, including those on the regional campus, students’ unfamiliarity with this service kept students from exploring and utilizing this resource.

In brief, it can be seen that both before and after the writing center closing, participants had access to and utilized some alternative writing support besides or in place of face-to-face tutoring at the writing center; however, the participants emphasized their preference for a physical writing center.

Discussion and Implications

In U.S. higher education, writing centers are a common institutional resource that provides writing support and writing-related events for students, and scholars have produced rich scholarship that focuses on the operations, functions, and impact of writing centers to legitimize, develop, and innovate writing center praxis. However, few inquiries have been conducted into the closing of writing centers, a starkly opposite line of investigation. With writing centers as important resources that facilitate college students’ writerly growth, how did the closing of a writing center impact the students it used to serve? How did the students cope with the loss of services previously offered by the writing center? The students at my writing center had a lot to say: although they acknowledged the low usage of the satellite writing center, they viewed it as an important resource that helps improve their writing and grades; additionally, they reported enjoying a sense of community and forming an attachment to the writing center by participating in featured activities. Toward the writing center closing, the students expressed sadness and disappointment, maintaining that the writing support should be offered to students. Meanwhile, after the writing center was closed, some of them utilized alternative writing support such as gaining feedback from family and using online tutoring services offered by the university writing center, while others did not seek out alternative writing support at all.

Students’ reactions—both emotionally and behaviorally—seemed natural and understandable. I was glad to be able to document their feelings, perceptions, and reactions through an empirical study, which not only composed the last chapter of my closed writing center through students’ own voices, but also enriches and complicates the writing center grand narrative (McKinney, 2013): rather than always depicting the writing center as “a cozy, homey, comfortable, family-like place” (p. 20) that is always there for students, writing centers can also be vulnerable and unstable despite the warmth and coziness on the surface; worse even, they can be taken away from students overnight, rendering them “homeless writers.” Gazing at the story that my participants constructed in their own voices through the survey and focus group, we can clearly see that the struggling and closing of writing centers are never inconsequential events that should be taken lightly; instead, they strike students emotionally, practically, and writerly, posing pressing questions for writing center practitioners and university administrators: what meaning can we make of the death of a writing center? How can we turn such meaning into useful knowledge that productively improves our practices as educators and administrators, especially during a time of constant changes and unpredictable challenges? Below, I offer discussion and implications based on my findings.

Writing Centers as Communities

As my findings illustrate, the participants in my study repeatedly voiced their appreciation of the featured activities sponsored by the satellite writing center, such as the pen-pal project and the Writers’ Meeting, which offered them opportunities to see a bigger world and meet more people, especially on a somewhat peripheral regional campus in a small town. Hence, the satellite writing center meant more than a tutoring service to the students; instead, they perceived the writing center as a community, where they not only sought for writing support but also built relationships, enjoyed exchanges of ideas, and explored the world and cultures outside of the regional campus. Cooper (2018) discusses the benefits of building community within the writing center, which “lead to high retention rates, more successful students post-graduation” (p. 2). In our writing center, the value of community was confirmed by the students: in their eyes, the existence of a writing center represented a form of support and a gesture of care, which contributes to the “campus life and climate” on the marginalized regional campus (Lerner, 2003, p. 73). Furthermore, my participants described their personal histories and connections with the satellite writing center—in detail and with emotions. Therefore, a careful look at the closing of the writing center offered students an opportunity to reflect on their personal connections to and experiences with the writing center, their perceptions and usage of campus support, and how they coped with the loss of a campus resource. For university administrators, this study urges them to revisit writing centers through its connections with students: when the decision of closing a writing center is made, a community collapses—so, which costs us more, sustaining a writing center, or losing a community? In cases where the closing of a writing center is inevitable, what can we do to sustain the sense of community that student writers experienced in the writing center?

Transitioning to Life without a Writing Center: Cultivating Resourceful Writers

An interesting finding in this study is: some students reported not seeking out alternative writing support at all after the satellite writing center was closed; in other words, the loss of the satellite writing center left the students supportless. Such help-seeking behaviors, or lack thereof, brings us to the discussion of writerly resourcefulness. When examining graduate-level writing support, Simpson (2012) points out that graduate student writers need a network of available writing resources with multiple points of entry; similarly, Mannon (2016) argues that graduate writers tend to seek writing support from a large feedback ecosystem, with writing center tutorials as one type of resource. Simpson’s (2012) and Mannon’s (2016) findings about graduate students’ help-seeking behaviors can be meaningfully extended to account for all student writers, and especially those who lack and/or are losing support. In the case of my study, besides empathizing with students who were rendered resourceless due to the loss of the writing center, more importantly, we could turn this disadvantage to an advantage by educating students to become resourceful writers. First, we should bring the concept of “writing resource network” to students. In my study, after the satellite writing center was closed, some students sought out no alternative writing support, and some of them stated that they had had no idea about the existence of online tutoring services offered by the university writing center on the main campus. This revealed how important it is to raise students’ awareness of writing resourcefulness and teach them to identify various available writing resources, such as online writing resources, office hours with professors, formal and informal peer reviews, writing groups, etc. As such, we could help students gradually customize and build an effective writing resource network based on the affordances of available resources and their own writing needs. Second, we should guide students to adjust their writing resource network in light of the changing reality and to actively seek out alternative writing support. For instance, after I completed this study, I developed a handout that lists various available writing resources for the students on the regional campus, which could be the first step to help them transition from the academic life with an in-person writing center to one without it. Therefore, by raising students’ writing resource awareness and guiding them to adjust their writing resource network, we could cultivate them to become more resourceful writers.

Not Only Resourceful but also Resource-savvy: Promoting Online Tutoring as a Flexible Form of Writing Support at the Time of Changes

While some students in my study reported not seeking out alternative writing support after the satellite writing center was closed, others reported their experience using online tutoring offered by the university writing center. Interestingly, these students, along with those who never used online tutoring, all expressed their preference for the availability of a physical writing center and the convenience of working face to face with tutors. This univocal preference for a physical writing center might be due to their lack of awareness of or familiarity with the online writing center, which is particularly worth our attention during a time of pandemic. As Williams and Takaku (2011) argue, “what affects students’ writing performance is not the writing center tutoring per se but rather the students’ help-seeking behavior—whether it is frequent and based on perceived needs” (p. 6). In my study, students clearly voiced their needs for writing support, regardless of the existence of the satellite writing center. Thus, the essential question here is: how can we reach students effectively, especially during the time of changes, such as when Covid-19 severely complicates and threatens the functioning of educational institutions in general and writing centers in particular? In other words, how can we help reshape students’ help-seeking behaviors and promote online tutoring as a flexible form of writing support? In my study, students preferred physical writing centers and face-to-face tutoring, due to its availability, convenience, and interaction; in addition, they valued the community offered by the writing center. Therefore, when we promote online tutoring during a pandemic, we should consider: How can we cultivate students to become resource-savvy writers who utilize writing support flexibly? Besides more marketing on the online writing center and teaching students to use online tutorials and workshops to increase their familiarity with online writing centers, how can we replicate the sense of comfort and community and, as Carpenter (2008) questions, “convey the inviting and supporting aura in our virtual spaces and consultations” (para. 1)? Slayton et al. (2021) offer innovative technological solutions to build an inviting online community at the writing center by embracing vulnerability and sharing creativity. Such discussion should go on in our field, because it is high time that our students become not only resourceful but also resource-savvy writers who can take advantage of available resources dexterously in the face of challenges and changes.

Conclusion and Future Research

When my satellite writing center disappeared abruptly, it did not even have the time to bid farewell to its students. Life continued on the regional campus and students kept writing papers. However, invisible repercussions might have occurred somewhere in some way; if such repercussions had remained unearthed, the story of the writing center would have been incomplete. The full story deserves to be told, and when it is told through students’ voices, knowledge is constructed about the significance of a writing center and how students responded to the loss of a valuable campus resource. To some extent, I am initiating a much-needed conversation at the writing center’s parlor: for writing center professionals in a similar situation—be it closing due to the lack of funding or indefinite shutdown due to the outbreak of a pandemic—let’s consider how to productively reach and serve our students in the face of drastic changes.

In light of the findings of this study, I invite future research to explore the following questions: How does the closing of a writing center impact students’ writing performance, in both qualitative and statistical terms? By the same token, how did students perceive and react to the temporary loss of face-to-face tutoring due to Covid-19? How have their writing-related help-seeking behaviors changed? How do they perceive and react to online tutoring, which might become the new normal for writing centers? What actions have been taken by writing center professionals to help students navigate this new normal and how effective are they? Although “farewell,” “closing,” “death,” and “shutdown” are not the most exciting words we desire to hear in the writing center narratives, inquiries into this side of the writing center story are nonetheless generative, intriguing, and meaningful.

Notes

- All the names used in this study are pseudonyms to maintain the confidentiality of the participants. ↑

- The online writing center service was provided through the university writing center on the main campus; in other words, when students from the regional campus utilized the online writing center, they would work with unfamiliar tutors rather than the two tutors at the satellite writing center. ↑

References

Carpenter, R. (2008). Consultations without bodies: Technology, virtual space, and the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 6(1). https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/62265

Cirillo-McCarthy, E. L. (2012). Narrating the writing center: Knowledge, crisis, and success in two writing centers’ stories (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Arizona). http://hdl.handle.net/10150/265336

Cooper, C. (2018). Building community within the writing center (Master’s thesis, University of South Carolina). https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5534&context=etd

Essid, J. (2018, February 22). From writing center to learning commons. [Conference session]. 2018 Southeastern Writing Center Conference, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States.

Farley, A., & Nealey, J. (2017, October 3). Writing Center closes due to lack of funding. The Tiger’s Roar. http://www.tigersroar.com/news/article_18362824-a865-11e7-a24d-9ff2c03abf1d.html

Lerner, N. (2003). Writing center assessment: Searching for the “proof” of our effectiveness. In M. A. Pemberton, & J. Kinkead (Eds.), The center will hold: Critical perspectives on writing center scholarship (pp. 58-73), Utah State UP.

Mannon, B. O. (2016). What do graduate students want from the writing center? Tutoring practices to support dissertation and thesis writers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 59-64.

McDonald, T. T. (2016, June 28). Students, staff angry over NJCU’s plans to shut down writing center. Nj.com. https://www.nj.com/jjournal-news/2016/06/students_staff_angry_over_njcu.html

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. University Press of Colorado.

Reese, D. (2018, February 22). It’s been a fun ride: Armstrong State University says farewell to the SWCA annual conference [Conference session]. 2018 Southeastern Writing Center Conference, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

Salem, L. (2014). Opportunity and transformation: How writing centers are positioned in the political landscape of higher education in the United States. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 15-43.

Simpson, S. (2012). The problem of graduate-level writing support: Building a cross-campus graduate writing initiative. WPA, 36(1), 95-118.

Spitzer-Hanks, T. (2016, March 30). The death of a ‘writing center’? http://www.praxisuwc.com/praxis-blog/2016/3/30/the-death-of-a-writing-center

Slayton, K., Howard, J., & Soto, R. (2021). “We are sharers”: Finding community in isolation. The Peer Review, 5(1). http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-5-1/we-are-sharers-finding-community-in-isolation/

Williams, J. D., & Takaku, S. (2011). Help seeking, self-efficacy, and writing performance among college students. Journal of Writing Research, 3(1), 1-18.

Acknowledgment

I extend my greatest gratitude toward my dear professors, friends, and family for their help and support, including Dr. Lynn Shelly, Dr. Ben Rafoth, Dr. Gloria Park, 梁丹凝, 赖财兰, 王丽文, 王宝, 阎栩, 阎杰, and 张云生.

Appendix A: Survey

1: During the fall 2017 semester, did you use the [Name of the Regional Campus] Writing Center, e.g., to meet with a writing tutor, participate in the Pen-pal project, attend the Writers’ meeting, leave your six-word memoir/thanksgiving note on the red poster on the wall right next to the library in the learning center, etc.?

A. Yes, I did

B. No, I did not

2: Which one(s) of the following writing center activities did you participate in and how many times? (You can select more than one.)

-

- Work with a writing tutor

- Write an email for the Pen-pal project

- Attend the Writers’ meeting

- Participate in poster writing

3: Which activity/activities do you consider the most helpful? Why?

4: Besides the [Name of the Regional Campus] Writing Center, where else did you obtain writing support during Fall 2019? (You can check more than one of the following sources.)

-

- My professors

- My peers, such as my classmates, friends, etc.

- My family, such as my parents, siblings, etc.

- The online tutoring service provided by the University Writing Center at [Name of the University]

- Others: _______________

- I did not ask for any additional support.

5: The [Name of the Regional Campus] Writing Center was closed at the end of Fall 2017. How do you feel about it?

Appendix B: Focus Group Questions

- I’d like to start our conversations with your experience with the [Name of the Regional Campus] writing center. During the last semester in fall, the [Name of the Regional Campus] writing center was still open and it provided different service and activities such as tutoring, the pen-pal project, Writers’ Meeting, and writing on the red posters at the learning center. Could you talk about your experience participating in any of these activities? How did you like it? For those who did not participate, could you talk about why you did not?

- The [Name of the Regional Campus] writing center was closed at the end of last semester. How do you feel about the closing of the writing center? Does it affect you in any way?

- This semester, when you need help with writing, who do you turn to or where do you obtain help?

- The University Writing Center of [Name of the University] offers online tutoring services in two forms: 1) You could schedule an online tutoring session and discuss your writing with a tutor through screen sharing. 2) You could submit your paper to the writing center and receive feedback from a tutor within 3-4 days. Has anyone used the online services before? Would you consider using this online tutoring service in the future? Why or why not?

- What does “not having a writing center” mean to you?