Heather N. Hill, Northwest Missouri State University

Natasha Helme, Northwest Missouri State University

Transfer of learning has become a common topic in composition and writing studies over the past few decades. Much research and discussion has gone into how we might create pedagogies that help students transfer their writing-related skills and knowledge more often and more effectively. In addition, the finding that transfer often needs to be “cued, primed, and guided” in order to be successful (Perkins & Salomon, 1989, p. 19), has prompted writing center scholars to consider how the writing center can help facilitate transfer since, it would seem, writing centers are a perfect place for students to get that kind of cuing, priming, and guidance. Although Bonnie Devet (2015) argues that our writing centers are already tutoring for transfer every day, we can do so more purposefully if we focus specifically on transfer by educating our tutors in transfer theory and making transfer a priority. Although scholarship has begun to look into the role of the writing center in facilitating transfer, this information is often difficult to get into the hands of the writing center practitioners who are often non-tenure track instructors or graduate students. Therefore, in this article, we focus on how I (Natasha), a second year MA student, learned about transfer, began using it in my sessions, and what I have learned about the positive impacts of transfer talk in tutoring sessions. After a discussion of my tutoring practice, we present the results of an IRB-approved focus group of students who had previously had sessions with me in the writing center. These students confirmed my impression that sessions that focused on tutoring for transfer were stronger and more beneficial sessions, and that we should continue to focus on transfer in our writing center.

Definitions of Transfer

In psychology and learning theory, the basic definition of transfer is the ability to learn something in one context and then use it in another. Whenever we ask about how knowledge gained in one context effects learning in another, we are asking about transfer. However, scholars have argued that this “carry and use” metaphor simplifies what students are really doing with their knowledge, and what we are really looking for when we conduct research on transfer (Wardle 2012b; Nowacek 2011; Driscoll 2015). Nevertheless, while we completely agree with these critiques, because transfer has become the most popular and understood term to discuss what we are talking about, we continue to use this term. However, in order to get at some of the complexity of what we are discussing, we want to define several types of transfer that we think are important to discussions of transfer in the writing center: positive vs. negative transfer, near vs. far transfer, high road vs. low road transfer, as well as what we mean when we discuss “transfer talk.”

Transfer of learning is said to be “positive” when the prior learning affects learning and performance in different situations positively, meaning that it helps the person more effectively complete the new task. Negative transfer, on the other hand, happens when people transfer knowledge inappropriately, or, in other words, when prior learning affects the new task negatively, causing the person to be less effective in completing the task. As discussed by Amy Devitt (2007b), negative transfer often causes problems for students trying to transfer their writing-related knowledge because students often attempt to use the same writing conventions in two different situations that require different conventions. For example, many students transfer the five-paragraph essay into First Year Composition (FYC) when instructors in those courses do not want that genre. This problem occurs when students do not accurately discern the similarities and differences between situations. Students may see two situations as similar and use the same genre conventions, when in fact the situations may be different and require different conventions. Recognizing similar situations, Devitt argues, may cause some writing skills to transfer, but only within the same genre. For example, a writer who learns to integrate and analyze quotes for a literary analysis paper will probably be able to use that skill in the next literary analysis paper, but trying to use this strategy in another genre may not work, and thus cause negative transfer.

Another way of talking about different kinds of transfer is the difference between what Perkins and Salomon (1989) call “high road” and “low road” transfer. These terms often correspond to the terms “near” and “far” transfer, but not always. Low-road transfer is transfer that happens automatically without the person making any conscious decisions to transfer that particular learning. For example, people transfer their knowledge of how to spell simple words without having to consciously think back on the time they were taught to spell that word, etc. Low-road transfer often happens in situations that are very similar, or situations that are “near” to the original situation where the information was learned. Negative transfer can occur, though, when students perceive two situations as being similar and use low-road transfer of writing skills or genres when they should not have. This occurred in Artemeva and Fox’s (2010) study of students in an engineering communication course who were asked to write a technical report. Only a very small percentage of students actually wrote a technical report, and these were students who had experience writing technical reports. All of the other students wrote typical school essays. The students automatically transferred in knowledge that was inappropriate because they assumed the situation was similar to other school-writing situations they had been in before. Situations similar to this one are what caused James (2008) to claim that it is not objective similarity that matters in transfer, but rather perceived similarity. If students do not see two situations as similar, they are less likely to transfer their learning between those situations. On the other hand, if students perceive similarity where the situations are actually different, this can cause negative transfer.

In contrast to low-road transfer, high-road transfer requires conscious reflection on past learning and a conscious decision to use knowledge gained in previous contexts. In order to achieve effective “far transfer,” or transfer to situations that are farther away (i.e., less similar) from the context in which the knowledge was gained, conscious reflection is often necessary. High-road transfer is often more difficult to achieve and thus often needs more prompting. For example, a student who is writing a lab report for a biology class might not automatically transfer knowledge gained in composition class without someone prompting them to reflect on their prior knowledge and how that might work in the new situation. This is where “transfer talk” can come into play, especially in a writing center. We are using the phrase “transfer talk” simply to mean any conversation or discussion that might prompt positive transfer. So, any time a writing center tutor is discussing a concept that might cause their students to effectively transfer their writing-related knowledge, they are engaging in transfer talk whether or not they are doing it deliberately.

Transfer and Classroom Writing Instruction

Early studies of FYC show that relatively little of what was taught in these classes transferred when students moved on to their other courses (Beaufort 2007; Carroll 2002; McCarthy 1987; Wardle 2007a). However, transfer is a fundamental goal of writing instruction. If students are unable to use what they learn in a writing class in other contexts, the value of the class is called into question. One major problem for transfer of writing-related knowledge is the fact that writing is context-specific, there is very little that can be called “general skills” in writing. Elizabeth Wardle (2017c) has recently argued that there is no such thing as “writing in general,” which makes it difficult for writing skills to transfer from FYC to other classes. Many studies (Carrol 2002; McCarthy 1987; James 2006; Bergman & Zepernick, 2007; Wardle 2007a; Beaufort 2009) have supported the notion that transfer of writing can be elusive. For example, “Understanding Transfer from FYC: Preliminary Results of a Longitudinal Study” (Wardle, 2007a) found very little evidence of transfer from her FYC class, even when students were taught with a focus on transfer. Even though students in her study claimed to have learned a lot in her course and could articulate what they had learned, they claimed they rarely needed to use what they learned. Students wrote very little and the writing assignments they did have were simple enough and similar enough to writing they had done in high school that they didn’t feel they needed to use anything from FYC in order to get good grades.

Because of the above studies, as well as others, it is now more commonly recognized that transfer does not happen automatically (Carillo, 2017). Transfer of learning, rather, has been found to be difficult for several reasons, not least of which is that knowledge is context-specific and thus difficult to generalize in ways that might be useful in new contexts. For example, David Smit claims that “there is reason to believe that what a writer knows or is able to do is very local and context-dependent and will not transfer to another situation” (p. 122). Theorists of situated learning (especially Lave 1988; Lave & Wenger, 1991) suggest that transfer may not exist at all, since knowledge cannot be decontextualized. Similarly, Devitt (2007b), in her “Transferability and Genres,” argues that transfer is difficult because different rhetorical situations call for different writing conventions. She claims that “any skills so generalizable as to be transferable from one situation to another would be so generalizable as to be virtually meaningless” (p. 217). These kinds of issues are what caused Perkins and Salomon (1999) to conclude that “transfer often simply does not occur” (p. 5).

In the wake of the studies showing failures in transfer, Composition scholars began to think about ways that we might change how we teach composition to make transfer more likely. What emerged is several pedagogical approaches that aimed at teaching composition with an eye towards transfer. Specifically, Amy Devitt’s (2004a) “genre awareness,” Downs and Wardle’s (2007) “writing about writing,” and Yancey, Robertson, and Taczac’s (2014) “teaching for transfer” all emerged as powerful alternatives to the ways composition had previously been taught. Although these approaches are not exactly the same, they have some major similarities. In each, the idea is that students leave the course with the vocabulary to be able to talk about writing in more accurate and complex ways. In each approach, students learn about writing. They learn that writing is context-dependent and that in order to be effective writers, they have to adapt to the particular situations they are writing for. They learn that there is no universal set of writing rules that can be learned in one context and then just used in multiple other places. They learn that they must be adaptive and flexible with their writing skills and that they must analyze each new writing situation to figure out the appropriate response. All of which (as argued by these scholars) are concepts that will likely transfer to other writing situations. These teaching for transfer approaches can only do so much, though. As mentioned in the introduction, a major finding of Perkins and Salomon’s (1989) research, is that transfer often needs to be “cued, primed, and guided” in order to be successful (p.19), which has brought the focus on transfer into the writing center because writing centers are a great place for students to get that cuing and guidance.

Transfer and Writing Center Research

In order to work toward the goal of helping students transfer their knowledge more often, writing center scholars have begun investigating ways that the writing center can (and already does) facilitate transfer. Many scholars agree with Devet’s (2015) claim that “transfer studies and writing centers are made for each other” (p. 138). One reason for this is, as Driscoll and Harcourt (2012) argue, “transfer is in accord with Stephen North’s (1984) all-too-well-known statement of centers helping to make better writers, not better texts (p. 438), especially since centers focus on writers transferring knowledge between assignments” (Devet, 2015, p. 139). Tutoring for transfer helps students reflect on their learning so that they can remember and use all of the broad knowledge they possess; it helps them understand how to approach new writing situations, how to analyze situations for their similarities and differences, and helps them understand key writing terminology (such as genre and rhetorical situation) that makes transfer more likely. Thus, in tutoring for transfer, we are not just helping students to improve the paper they bring with them to the writing center; we help them to become better writers overall. Hopefully, in transferring the knowledge they gain from the writing center, students will improve their approach to writing and thus be more prepared for the multitude of writing situations they may encounter in their futures.

Demonstrating the potential of the writing center to help facilitate transfer, Bromley, Northway, and Schonberg’s (2016) “Transfer and dispositions in writing centers: A cross-institutional mixed-methods study” investigates what students are able to transfer from their writing center tutoring sessions to the writing tasks they complete subsequently, as well as how the writing center helps students take on the dispositions that make transfer more likely. Their cross-institutional study used exit surveys and focus groups at three colleges of various types and sizes to investigate students’ perceived potential for future transfer and reported transfer of writing strategies they had learned in the writing center. The survey results showed that students believed they would be able to use things they learned in their writing center sessions when completing future writing tasks, and in later focus groups, students reported having actually used the strategies learned in the writing center. In addition, the findings indicated that writing center sessions sparked meta-cognitive awareness, increased confidence, and caused positive dispositions that have been shown to increase the likelihood of transfer (Reiff & Bawarshi 2011; Wardle 2012b).

Many of the other studies that investigate transfer in the writing center focus on the education tutors need in order to effectively facilitate transfer in their sessions. For example, working under the assumption that if we want tutors to be able to do this kind of work we have to teach them how to do so, Hill (2016a) gave half of her tutors a one-hour class on transfer theory and then had them (as well as those who had not been in the class) record their tutoring sessions for the next 3 months. She then analyzed the recordings in order to see the differences. The major findings of this research showed that those who had been in the transfer course engaged in transfer talk with their students at a much higher rate than those who had not. However, a more important finding for our purposes is that even those who had been in the class were unprepared to do this kind of work in a really effective way. The tutors needed much more education than a single one-hour class could give. They needed to have a much more complex understanding of both transfer and other writing concepts that lead towards transfer: genre, discourse community, disciplinary writing conventions, rhetorical situation, etc.

Agreeing that tutors need education in transfer theory in order to effectively facilitate transfer, several scholars have published guides to teaching tutors how to do that kind of work. In Transfer of Learning in the Writing Center (2020), three articles focus on tutor training (Bowen & Davis 2020; Hastings 2020; Hill 2020b). While the approaches to educating tutors in these articles are not exactly the same, they have some significant overlap. For example, these scholars agree that tutors need to have a deep understanding of transfer theory in order to effectively facilitate transfer. In addition, while Hastings focuses on teaching tutors about theories of how people learn, Bowen, Davis and Hill agree that tutors must have an accurate and complex understanding of how writing works, and they must be able to accurately discuss key concepts about writing that encourage transfer (concepts such as genre, discourse community, disciplinary writing conventions, etc.). Specifically, Bowen and Davis adapted the approach in Teaching for Transfer (Yancey et al., 2014) to classroom teaching to the writing center. Ultimately, these scholars argue that tutors need to have a strong understanding of transfer theory as well as other theories of how people learn, have an accurate and complex understanding of how writing works, understand key concepts that encourage transfer, and recognize the benefits of reflection and meta-cognitive practices. As we will see in the next section of this paper, these are the same kinds of theoretical knowledge that Natasha possessed, which enabled her to facilitate transfer effectively in our writing center.

Although we have highlighted several studies that take diverse approaches to writing centers and the question of transfer, the common thread throughout this scholarship is the idea that transfer is a complex process that does not happen automatically, that the writing center is an ideal place for students to get help in transferring their learning more effectively, and that tutors need to be educated in transfer theory if we want them to be able to do that kind of work. In this article, we hope to be able to show how having a high level of knowledge of transfer and how it can be applied to writing center sessions benefit the students who come to the center. The graduate student in this study (Natasha) had an original tutoring education experience that was not focused on transfer. However, she had been studying transfer as a graduate student and had done extensive secondary research on transfer for an International Writing Center Association presentation. In addition, she had worked as a research assistant on a project on transfer in the writing center. Therefore, she was highly educated in transfer theory and used it regularly to help improve her practice. In the next section, she will explain her practice in her own words, and we will follow with the results of a focus group with several of her students. We hope that this discussion will give some insight into how tutoring for transfer can be accomplished and support the argument that writing centers should put transfer at the forefront of their tutor education programs.

Tutor Transitions: From Tacit to Explicit Tutoring for Transfer

I (Natasha) am a second-year graduate student and graduate assistant for the Writing Center at our university. As a graduate assistant at the Writing Center, I put together our schedule and helped tutors learn about tutoring practice and, specifically, how to implement transfer into their sessions. I also went to the same university as an undergraduate and worked at the writing center during that time as well. During my time as an undergraduate student, I worked at the Writing Center for three years as a writing tutor and for two semesters as a writing fellow in our Introduction to College Writing courses. I also worked for the Student Success Center as the Western Civilizations II Supplemental Instruction Leader and the Western Civilizations tutor. So, as you can see, I had a good amount of experience in tutoring. However, I did not discover the idea of transfer theory until the Senior year of my undergraduate education.

I was educated in tutoring practice by someone who no longer works at our university. My training consisted of taking our writing center training class, which was taught by the then Writing Center Coordinator. In that course, we focused on how to tutor outside of our academic discipline, handling various situations that could happen during a session, and crafting our personal tutoring philosophies. We were also supposed to have a tutor mentor who would have us sit in on some of their sessions, sit in on some of our sessions, and then debrief about the sessions after they were over. However, I ended up being mentor-less for the majority of my training because the returning trainer who was assigned as my mentor left the center. As a result, I developed a tutoring style that was rather different from many of the other tutors because I was essentially dropped into the deep end of a swimming pool without floaties and having no idea how to swim because I didn’t know anything about writing tutoring beyond “don’t edit their papers.”

I really didn’t know what transfer theory was until Heather became the writing center director in my third year of tutoring and told me about it. However, while I didn’t know what it was called, I had already been using it to some extent during my sessions for the two previous years I had been tutoring. As Devet (2015) has claimed, writing centers are already tutoring for transfer all the time, and that was the case for me whether I understood what I was doing or not. I remember first encountering something like transfer theory during elementary school. I had an individualized education plan, or IEP (which is typically used for someone with learning disabilities), from third to seventh grade and I remember several of my IEP teachers in elementary school saying stuff like “x is a lot like y” and that it always helped me better understand whatever I was working on, so I decided to try using that model during my tutoring sessions.

I first used this model during a session with a first-year science major. They were struggling to understand what a thesis statement was and why it had to be in their FYC paper. After talking with them about what they thought a thesis statement was, I realized they didn’t know that a thesis statement is supposed to state the paper’s central claim. I asked them to describe what a hypothesis was and how it functioned in a lab report. They told me that it was a statement that told the person reading the report what the report would be about. We were then able to work towards the idea of a thesis statement because of its similarities to a hypothesis. We were able to take something the student already knew and apply it to a new writing situation. In that student’s own words, a “lightbulb clicked” and they were able to write an effective thesis statement for their paper. Since this session was successful, I decided to use that method whenever it was possible. I have found that this approach works for most students, and that knowledge, combined with what I was learning about transfer and genre theory in my graduate studies, prompted me to explore other ways of using transfer during my sessions.

One of the things I started to talk about a lot during my sessions is how we tend to build puzzles as we learn to write in different genres. I talk to my students about how one piece of a puzzle will not work for a different puzzle simply because they are from different puzzles, just like how a writing convention can work for one genre but not work for a different one. An example of this would be a student who was trying to force a five to six page historical analysis into a five-paragraph essay. The student genuinely believed the only way to write a paper was to have an introduction paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion paragraph, and that anything other than that would result in a failing grade. We talked about how historical analyses are not the same kind of paper they would have written in high school because while they are a similar genre, they are much more complex, which means that they really can’t fit into five paragraphs. We ultimately concluded that the historical analysis was like a 1,000-piece multi-chromatic puzzle while the five-paragraph essay was like a ten piece puzzle, and that it would be very difficult to successfully cover all the information required by the prompt in five paragraphs because there would be many different ideas in each paragraph. We also talked about how some genre conventions will have some overlap, such as every paragraph being indented or words from different languages being italicized, or how both a five-paragraph essay and five to six page historical analysis typically have a central claim and evidence to support that claim. This helped the student understand when to transfer their knowledge and when they might have to adapt that knowledge for slightly different writing situations.

Another example of how I use transfer talk is in the ways I talk about formatting and citation styles outside of the student’s academic discipline. Because I was an undergraduate history major, I know Chicago/Turabian formatting and citation styles pretty well, so I tend to either be scheduled with the students with Chicago/Turabian questions or asked questions via our center’s GroupMe. During these instances, I’ll often say something like “footnotes are a lot like MLA’s in-text citations, but you have a number in the text and word at the bottom of the page instead of parentheses and words in the middle of the text.” I think that using this type of transfer talk is incredibly beneficial for students because it helps them feel like they are not learning something completely new. I know I and many of my historian peers felt very nervous and lost when we first started to learn and use Chicago/Turabian in our notoriously difficult introductory history class. I’m sure that if my peers and I felt nervous and lost, then the students I tutor probably feel the same way. However, by saying something like “this is a lot like something you already know,” we help our students feel more comfortable with what they’re working on, and therefore have a more productive session and take one step forward on their journey to becoming a better writer.

Although not all sessions can use transfer theory, the sessions that I can and do use transfer theory always seem to be better than the ones where I could have but didn’t use transfer theory. The students who engage in transfer-talk in their sessions seem to have a better understanding of the concepts we cover during their session than those who did not have transfer discussions. I’ve also seen a significant difference in my fellow students when transfer theory is used during their sessions. For example, I will ask them what their greatest writing challenge is at the end of their sessions and talk about what they identified as their greatest weakness. About half the time, their greatest weakness stems from a writing convention from a different genre than what we are working on in their basic writing class, so we’ll talk about how and why they are different. As a result, we’ll look over notes they have from class, what is stated in their textbook, or I show them something I do during my own writing process. I also help them decide the pros and cons to each approach, if they think it would be an effective strategy to them, and how to implement it in their writing process if they choose to do so.

One of the issues related to transfer theory is that it will not always occur in every session. Sometimes we can’t really initiate transfer talk in our sessions for a variety of reasons, or it doesn’t really make sense to bring in transfer talk. Sometimes we just get so focused on the assignment or something else that transfer talk doesn’t happen. An example of this is when one of the upper-division history student comes in for a session with me, particularly those in the history department’s capstone class: Research Seminar. A lot of times, we end up brainstorming research questions, looking through databases and catalogs, or searching our university’s microform archive. In these cases, it doesn’t always make sense to bring in transfer discussions, and that’s fine. Transfer doesn’t need to come up in every single session. However, the sessions where it can, organically, be part of the discussion typically seem to be better sessions than those where it doesn’t.

Another major benefit of transfer theory in writing center sessions is how it can help to minimize the possibility of negative transfer. I’ve learned different methods of reducing the chances of this happening and reducing how much it affects students. I’ve mentioned this a few times in the examples above, but I would like to reiterate and emphasize how transfer theory helps reduce negative transfer. In the case of the first semester science major, once we acknowledged that her lack of knowledge about thesis statements was hindering her writing, we were able to discuss how thesis statements are like hypotheses. However, it was imperative that we made sure that she understood that thesis statements and hypotheses are not the exact same thing because she would not refute her thesis statement because that would defeat the purpose of the genre she was writing in. So, in helping this student discover both the similarities and differences between a thesis and a hypothesis, it helped her transfer their knowledge effectively without negative transfer.

In the case of the student writing the five to six page historical analysis, discussing different genre conventions helped them see that a five-paragraph essay cannot work for a five to six page historical analysis because they require specific genre conventions, just like how a puzzle requires specific puzzle pieces. However, through our discussion, the student also discovered that many genres (especially academic genres) will have some overlap. Again, the student discovered the similarities and differences between the two genres so that they could transfer their knowledge effectively.

Similarly, in the case of students learning citations and formatting, the student came to recognize that the new guidelines and styles are not like an isolated island because we identified similarities between the new and uncomfortable guidelines and styles with a guideline and style they are more familiar and comfortable with, but again, we made sure to discuss that even though certain aspects of the formatting styles and citation guidelines are similar, they look and function differently. Therefore, negative transfer is less likely to happen to this student when it comes to citation guidelines and formatting styles because she was able to identify and understand the similarities and differences between various citation guidelines and formatting styles. In addition, these discussions helped her have a less stressful experience while learning something that tends to make most people nervous, which is always great because many of our students experience stress when they write.

Finally, in the case of going over what the professor says, what the textbook states, and sharing personal writing process procedures, the student and I collaborated to isolate information they may need from their professor, textbook, or myself and figured out how to implement those into their writing process. However, we always want to make sure students are aware that there are always other options and other ways to implement something into their writing process. Therefore, negative transfer is less likely to occur because the student identified multiple sources of information, learned how to distill that information, and how to implement it into their writing process if they feel it would be beneficial.

These are only a few of the ways that I have used transfer in my tutoring sessions. In the following section, we discuss the results of a focus group of my students in which they discuss the effectiveness of my practice and which sessions they felt were stronger and more beneficial to them.

Student Focus Group

Five of Natasha’s students were chosen at random to participate in a focus group about the effectiveness of the tutoring sessions they had with her. All of them had met with her at least once within the previous month; several of the students had met with her multiple times over the course of the previous year. None of the students originally requested to work with Natasha; they were either assigned to her or she was the one available when they came as a walk-in. However, the two who had worked with her more than once had requested her. All of the students were either currently taking our First Year Composition course or had taken it within the past year and had originally come to the writing center to work on papers for their FYC class. All of the students were freshmen or sophomores and came from a variety of majors.

To get the most objective and candid answers from the students, Natasha was not present at the focus group meeting. The focus group was conducted by Heather, instead. Because we wanted them to be able to recognize and specifically talk about moments of transfer talk, I (Heather) first defined the word “transfer” for the students. The questions then focused on whether the students thought a transfer approach was beneficial to them and other students who came to the center, if and how Natasha used transfer in their sessions, and whether they thought that was helpful to them. The purpose of the focus group was to help us see how Natasha’s practice affected the students she worked with and how effective they thought it was. While it is possible that the students in the focus group told me what they thought I wanted to hear, I was very clear in telling them that we were investigating the effectiveness of our current focus in the center and thus wanted to get their honest feedback about whether they thought it was helpful or whether they thought we should change to a different approach. While there may have been other ways of gathering this information, a focus group was the best way of getting feedback on whether Natasha’s approach in her sessions was helpful to her students.

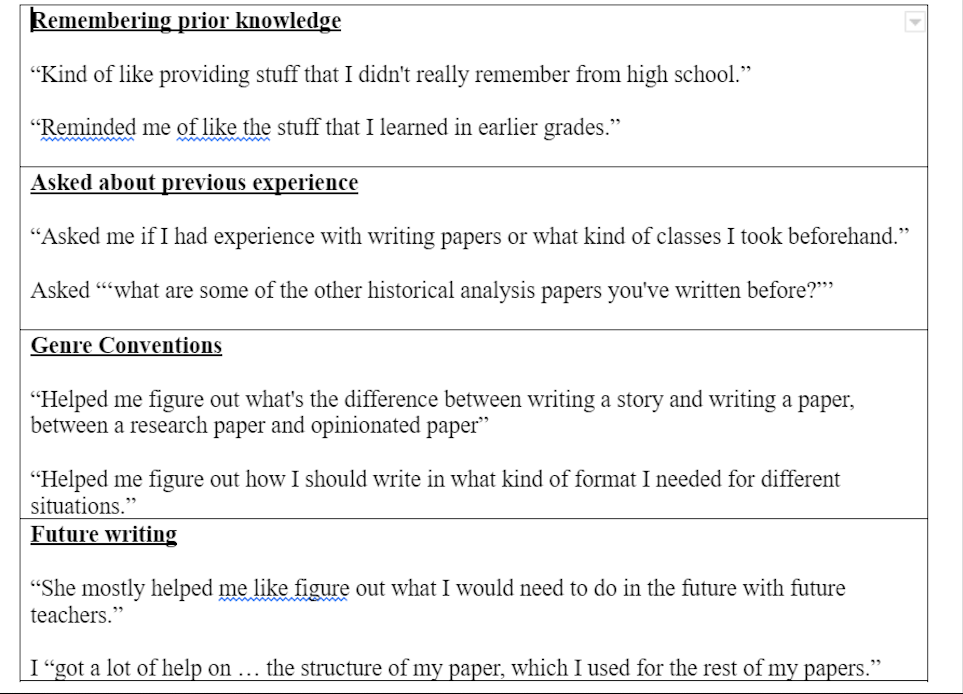

The students focused on four main ways that Natasha helped them transfer their knowledge: By helping them to remember specific things they had learned in the past, by asking them general questions about their previous writing experiences, by helping them understand the similarities and differences in genre conventions, and thus avoid negative transfer, and by teaching them writing skills that they were able to transfer to subsequent writing situations. The students unanimously agreed that focusing on transfer of learning seemed like a good approach. For example, one student said, “I think it’s a really good idea. Just to kind of keep at that information … how you kind of want to implement the stuff that you’ve learned and keep building off of that.” Another student said that “the concept of learning from what you did [previously] from the writing center is a lot more helpful than most people would think.” A third student answered that the transfer of learning approach “is actually helping students with a lot more than just writing a paper.” Chiming in after that, student four argued that it “helps you not with just that specific paper, but future papers too, since you can take what, you know, what they can teach you for other stuff, other than just that one paper.” So, as you can see, the students thought the transfer of learning approach was beneficial to them.

When we moved on to talking about their experiences in sessions with Natasha, they began by focusing on the ways that she helped them to remember things they had learned in the past that would help them in the current writing situations. While Student one said that she “just went in for citation help,” everyone else mentioned transfer and ways that Natasha had helped them transfer their knowledge. For example, Student five stated that Natasha “kind of reminded me of like the stuff that I learned in earlier grades, like kind of like the basic stuff to writing a paper. [She] kind of reminded me of that … which I think was really helpful instead of just focusing on like the content.” Student two added that she had “kind of forgot kind of how like the basics of writing a paper, like how important those were,” but that Natasha reminded her of what she had learned previously and “that was something that definitely helps me moving forward.” Student four added that in “school today, like you kind of learn the stuff for the test and then you kind of forget about it and then move on. So, I thought that was nice to kind of revisit some of the old stuff that I’ve done and what worked for them. I thought that was a helpful approach.”

In addition, Natasha helped students remember previous knowledge by asking general questions about their previous experience writing similar papers or writing for similar classes. Student three said that Natasha “asked me if I had experience with writing papers or what kind of classes I took beforehand for writing so she could get a better knowledge on how she would approach and what kind of examples she could have given me to like make my paper all the more better.” This type of general transfer talk was echoed by others as well. For example, Student 4 said she:

was asked [those kinds of questions] a couple of times throughout my different visits. It usually started [with] what classes have you taken? Like how many of, what kind of papers have you written? And those kinds of questions. And then … because I was writing a historical analysis paper, she was actually like, “okay, so what are some of the other historical analysis papers you’ve written before?” And I told her about two of them. And she was like, “okay, what kind of comments did your teacher give you there that you could implement in this paragraph? Or like this paper here?” And I thought that was helpful.

Student three agreed, stating:

She did ask me kind of what papers I’ve written in the past. And if I had done anything kind of with like the citations like that, just to help me try and understand it, not just be able to just tell me like what to do. She was trying to get me to like, think more about other things I’ve done and how I could help with this paper specifically … She was just trying to help me understand with like what I’ve done in the past, trying to, I don’t know, like made it easier since I’ve already done something similar kind of like an explanation.

The students also mentioned ways in which Natasha helped them understand that different writing situations require different writing conventions (thus helping them avoid negative transfer). For example, Student five stated that she “just went in for help for a topic that [she] was talking about. But after talking, she [Natasha] helped me figure out what’s the difference between writing a story and writing a paper, between a research paper and opinionated paper, versus like a story that I’m writing.” Student 4 agreed, stating “she mostly helped me figure out how I should write in what kind of format I needed for different situations and stuff like that, which really became helpful in the long run when I needed to write reports whenever I need to write stuff for my job, and stuff like that. So, it actually helped me out in real life and in school.”

When we moved into talking about whether Natasha had helped them think about how they might transfer their knowledge to future situations, Student one stated that “she didn’t really help me think about like the future.” However, others disagreed. For example, Student 2 stated that she “helped me like figure out what I would need to do in the future with future teachers … She talked about her experiences with teachers and how most of them wanted types of formats, types of ways that they like papers being written and stuff like that. So that mostly helping me out with some of my teachers in the long run.” Student three added that Natasha “said that I could use what she had kind of shown me about like transitions and citing for other papers that were similar, like research papers. I’d have to tweak it just a little bit. So it’d be more appropriate for that specific paper, but I could use it as like a general starting place.” Student five added that she “got a lot of help on … how to structure my paper, which I used for the rest of my papers. I learned about like thesis statements and then about citations. Those are stuff that I directly, I observed really quick. And then I was able to implement in later papers. So that was really helpful.” So, while Natasha might not have helped every student think about future writing situations, most students claimed that they learned things in their sessions that they were able to use in future writing situations.

In the end, students seemed very receptive and even grateful for the transfer of learning approach in their tutoring sessions (Table 1). Student three summed it up nicely when she said:

I really liked how she made me think about like previous papers I’ve written to try and show me like examples of, I have actually kind of done something like this before. So it wasn’t like, it wasn’t completely new … once she kind of reminded me of things I’ve done in the past, it did make a little bit more sense because I was like, Oh yeah, I guess I did do something pretty similar to this. It just made it easier for me to understand.”

Table 1: Examples of Student Responses

Implications: Where to Go from Here

In Hill’s 2016 study of writing centers and transfer, she discussed five pedagogical conditions that can help students transfer their knowledge more often and more effectively: 1. Having a high level of initial knowledge; 2. Understanding the similarities and differences in writing situations; 3. Reflection on past writing situations; 4. Certain dispositions towards transfer (active learning, internal motivation, etc.); and 5. Understanding abstract concepts about writing that transcend individual situations (p. 80-82). Throughout Natasha’s discussion of her practice and the focus group with her students, we see that many of the transfer discussions were about these kinds of things.

Students come to the writing center to get additional help on things they are learning in their classes, and tutors help reinforce that learning so that students will remember it and be able to use it later. So, helping students have a high level of initial learning is exactly what the writing center is doing every day. Natasha specifically helped students with this when she helped them with improving their thesis statements, their use of citations, and other things they were learning in their courses. Secondly, many of the transfer-facilitating discussions focused on reflecting on past knowledge or helping students see the similarities and differences between writing situations. In addition, none of the students in this study were forced to go to the writing center as part of their course requirements, so this already shows initiative and a disposition towards active learning and motivation. Thus, these students seem to be the kinds of students that would be more likely to transfer their learning (Wardle, 2012b). Lastly, the fact that writers must adapt their writing to each new writing situation is also a more abstract concept that could help facilitate effective transfer because it transcends the individual paper the students brought with them to the writing center. Also, when Natasha mentioned the puzzle metaphor in her narrative of her tutoring practice, she gives us a good example of an abstract idea that students can take with them and use in subsequent writing situations.

To distill this down to an easy-to-use reference: here are four ways that transfer talk can be used in tutoring sessions to help students transfer their writing-related knowledge more often and more effectively (and avoid negative transfer):

- Help them see how what they are currently doing is similar to what they have learned to do in the past. It’s as simple as saying something like “X is similar to Y” and showing them how to apply what they already know how to do. This is especially helpful if the tutor knows that students have learned something in previous classes. For example, asking students about what they have previously learned about writing thesis statements can help them remember their previous papers and how they were taught to write thesis statements in those papers.

- Use metaphors and analogies to show them why things work (or don’t work) in certain ways. The puzzle metaphor works very well when talking about genres, but other tutors have used sports metaphors and other analogies. For the directors, this could be a great activity for your tutor education course: have tutors come up with metaphors and analogies that they could use to help their students understand how to transfer their knowledge more effectively.

- Help students understand the differences in writing situations, which is essential for preventing negative transfer. Students often come to college thinking that the five-paragraph essay is all they need to know, and as Natasha showed, they often try to use that genre in situations where it shouldn’t be used. Helping them understand how the situations are different, will help them avoid negative transfer and write more effectively in future situations as well.

- Help students understand abstract concepts such as “genre” or “disciplinary writing conventions” or “discourse community,” etc. These abstract concepts apply to multiple writing situations and an understanding of these will help them write more effectively overall. In Yancey et al.’s (2014) teaching for transfer approach to teaching first-year composition, teaching these kinds of key concepts is essential to helping students transfer their knowledge. Thus, a writing center focusing on tutoring for transfer should also work on teaching students these kinds of abstract writing concepts.

While we have argued for the value of using a transfer approach in the writing center, we understand that no approach is perfect and that in deciding to use one approach over another, there are always pros and cons. For example, there may be fear that tutors begin to act as disciplinary experts when they should not do so. However, if tutors are focusing on abstract principles of writing studies that facilitate transfer (genre, disciplinary writing conventions, reflection, etc.), there is less likelihood of that happening. Overall, we believe that using transfer theory in sessions will improve most sessions if we operate on the principle that we, as tutors, help make better writers and not better papers. Transfer theory is about helping writers see connections between writing contexts, genres, and anything else writing related they may or may not recognize by themselves. It helps them learn how to be better writers and how to become better writers independently from their professors and tutors. At the end of the day, our job as tutors is to help our students recognize their strengths and weaknesses as writers, show them different methods and tools to improve, and encourage them to learn how to help themselves during their writing process. Transfer theory helps all this happen. This research illustrates the good work that can be accomplished in this area when tutors are highly educated in transfer theory. Thus, we advocate for a tutor education program that focuses on teaching tutors to facilitate transfer in their tutoring sessions.

References

Artemeva, N. & Fox, J. “Awareness Versus Production: Probing Student’s Antecedent Genre Knowledge. Journal of business and technical communication, 24(4), 476-515.

Beaufort, A (2007). College writing and beyond: A new framework for university writing instruction. Utah State University Press.

Bergman, L., & Zepernick, J. (2007). Disciplinarity and transfer: Students’ perceptions of learning to write. WPA: Writing Program Administration, 31(1-2), 124–149.

Bowen, L.M. & Davis, M. (2020). Teaching for transfer and the design of a writing center education program. Transfer of learning in the writing center: A WLN digital edited collection. Devet, Bonnie, and Dana Lynn Driscoll, editors. https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection2/.

Bromley, P., Northway, K., & Schonberg, E. (2016). Transfer and dispositions in writing centers: A cross-institutional mixed-methods study. Across the Disciplines, 13(1), 1–15.

Carillo, E. (2017). Writing knowledge transfer easily. In C.E. Ball and D.M. Loew (Eds.), Bad ideas about writing (pp. 34-37). West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute.

Carroll, L. A. (2002). Rehearsing new roles: How college students develop as writers. Southern Illinois University Press.

Devet, B. (2015). The writing center and transfer of learning: A primer for directors. The Writing Center Journal, 35(1), 119–151.g

Devitt, A. (2004a). Writing genres. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Devitt, A. (2007b). “Transferability and Genre.” The locations of composition.Weisser, C. R., & Keller, C. J., Eds. State University of New York Press.

Downs, D., & Wardle, E. (2007). Teaching about writing, righting misconceptions: (Re)envisioning “first-year composition” as “introduction to writing studies.” College Composition and Communication, 58(4), 552–584.

Driscoll, D. L., & Harcourt, S. (2012). Training vs. learning: Transfer of learning in a peer tutoring course and beyond. Writing Lab Newsletter, 36(7–8), 1–6.

Hastings, C (2020). Playing around: Tutoring for transfer in the writing center. Transfer of Learning in the Writing Center: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. Devet, Bonnie, and Dana Lynn Driscoll, editors. https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection2/.

Hill, H. N. (2016a). Tutoring for transfer: The benefits of teaching writing center tutors about transfer theory. The Writing Center Journal, 35(3), 77–102.

Hill, H.N. (2020b) Strategies for creating a transfer-focused tutor education program. Transfer of Learning in the Writing Center: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. Devet, Bonnie, and Dana Lynn Driscoll, editors. https://wlnjournal.org/digitaleditedcollection2/.

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge University Press.

James, M. A. (2008). The influence of perceptions of task similarity/difference on learning transfer in second language writing. Written Communication, 25(1), 76–103.

McCarthy, L. (1987). A stranger in stranger lands: A college student writing across the Curriculum. Research in the Teaching of English, 21(3), 233–265.

North, S. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446.

Nowacek, R. S. (2011). Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Southern Illinois University Press.

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1989). Are cognitive skills context bound? Educational Researcher, 18(1), 16–25.

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1999). The science and art of transfer. The thinking classroom: The cognitive skills group at Harvard Project Zero. Retrieved from http://learnweb.harvard.edu/alps/thinking/docs/trancost.htm

Reiff, M. J., & Bawarshi, A. (2011). Tracing discursive resources: How students use prior genre knowledge to negotiate new writing contexts in first-year composition. Written Communication, 28(3), 312–337.

Smit, D. (2004). The end of composition studies. Southern Illinois University Press.

Wardle, E. (2007a). Understanding “transfer” from FYC: Preliminary results of a longitudinal study. WPA: Writing Program Administration, 31(1-2), 124–149.

Wardle, E. (2012b). Creative repurposing for expansive learning: Considering “problem-Exploring” and “answer-getting” dispositions in individuals and fields. Composition Forum, 26(1), 3.

Wardle, E. (2017c). You can learn to write in general. In C.E. Ball and D.M. Loew (Eds.), Bad ideas about writing (pp. 30-33). West Virginia University Libraries Digital Publishing Institute.

Yancey, K. B., Robertson, L., & Taczak, K. (2014). Writing across contexts: Transfer, composition, and sites of writing. Utah State University Press.