Lucia Pawlowski, St. Catherine University

Abstract

I urge writing centers to assume more prominent roles in our institutions as exponents of linguistic antiracism. To this end, I present a scaffolded approach to talking about linguistic antiracism to all writing center stakeholders–especially the skeptics of antiracist work. The scaffold consists of three levels; I suggest that, in our outreach, we begin conversations about linguistic antiracism with the beginner level of “Linguistic Diversity,” then move on to the intermediate level of “Linguistic Equity,” and save the advanced level of “Linguistic Justice” for when our audience might respond to that level without backlash. Developing a strategy like this can empower us to embrace the challenge of advocating for linguistic antiracism. If any campus player can speak to how language, power, and identity are intertwined in the act of writing, it’s writing tutors. Therefore, in terms of doing antiracist work like this: if not us, then who? This article also argues for workplace democracy wherein tutors lay claim to central writing center operations such as antiracist commitments. Finally, this article wrestles with the ethical issues inherent in a white writing center director like myself adopting this particular strategy.

Keywords: Race, Equity, Faculty Development, Pedagogy, Linguistics, Standard Written English, Imperialism, Decolonization, Anti-racism, Linguistic Diversity, Linguistic Justice, Social Justice Movements, DEI, Whiteness, White Supremacy, Activism, Outreach

The What and How of Linguistic Antiracism

The body of research on antiracist writing assessment, antiracist writing center praxis, and linguistic antiracism is growing. The problem is not a dearth of research. And the problem is not always getting buy-in within our field: we see a movement among writing center professionals that at least acknowledges the need for antiracist theory and praxis in our field. Many writing center professionals have even managed to get some powerful people at our institutions on board with the claims of this research. What we need, as I posit here, is a schematic—a more organized techne—of having productive conversations with faculty, students, and staff on our campuses about antiracism, a schematic that takes into account where our audience is in terms of its skepticism or openness to antiracist work.

The focus of much of this movement within writing centers is on one aspect of antiracism in particular: linguistic antiracism. This makes sense because, as writing center professionals, if writing is the centerpiece of what we do, then we must make language, textuality, and writing our object of study—and embedded in writing and especially writing instruction is writer and reader identity. Racial identity, I would argue, should be of primary importance because of the history of writing programs and writing centers as exponents of “white language supremacy” (Inoue, 2021).

For the purposes of this project, my working definition of linguistic racism is racism directed at people of color for speaking a non-English language in the U.S. such as Chinese; or a Global English of the Global South such as Kenyan English; or a marginalized U.S. linguistic variety spoken by BIPOC people such as Black English. The definition I offer here synthesizes definitions gleaned from various studies in the field of Writing Studies, including those by Shapiro, Baker-Bell, Young, and Inoue, whose work I discuss throughout this article.

The intent of this piece is to get writing centers to see our ethical obligation and our power to join this movement. Until writing centers assume a more prominent role in our institutions as repositories for knowledge and vocal practitioners around linguistic justice, it is not just writing centers but academia more generally that will remain linguistically racist. Writing centers must work not just internally to become linguistically antiracist from within; writing center professionals need to make outreach—not just to faculty, but to staff, upper administration, and even the Board of Trustees—central to what we do if we are to create a linguistically just world. “Outreach” in this article is meant to be an umbrella term for everything from how we market ourselves, to the faculty development programming we offer, to even the conversations we have in passing with any university stakeholder. Again, those stakeholders are not just those who teach writing, but students, staff, administration, community members, and/or the Board of Trustees at your institution.

The reason why writing center professionals should make outreach a cornerstone of our operations is because we in fact have the institutional ethos to do so. Writing center workers bear the most intimate witness on campus of the effects of linguistic racism, and the power of linguistic antiracism: in one-on-one consultations, we, first, see the frustration of students who have experienced linguistic (and all types of) racism; and, second, through our expertise with all things textual, we work with the minutiae of how language operates in texts by writers who have been subject to various racisms. We bear this witness. If any campus player can speak to how language, power, and identity are intertwined in the act of writing, it’s writing tutors. When it comes to advocating for linguistic antiracism, if not us, then who?

We must do something with this ethos and not let it go to waste. Although having ethos is not synonymous with having power, certainly ethos can be leveraged to build institutional, social, and political power. When we look at the history of progressive movements in the U.S., for example, we see again and again how often it is those most affected by injustice—those with powerful ethos—who are able to gain enough power to prevail in the struggle for justice. I believe that the same can be true of writing centers: despite what usually feels like a (perhaps too well-documented) dearth of institutional power ascribed to writing centers, in fact writing centers have powerful ethos because of that act of witnessing. This ethos can translate into institutional—and perhaps extra-institutional—power. This article will hopefully offer one way to translate ethos into power.

If we accept that it is in our power to do effective antiracist work, we must take the task of outreach seriously. But how can we actually be effective in our outreach work, and move the needle in terms of skeptics’ attitudes toward our antiracist work? In this article, I propose that we “scaffold” our approach in conversations about race and racism within and outside the writing center. The same way we have introductory, intermediate, and advanced writing courses, so we might imagine a similar curriculum, if you will, for such conversations. I imagine the scaffold being most effective for people at our institutions and beyond who are skeptical of antiracist efforts, especially around linguistic antiracism, and/or people who are new to conversations about race, racism, and linguistic racism1. My hope is that such a scheme will prove more rhetorically effective and actually bring about more meaningful change at our institutions.

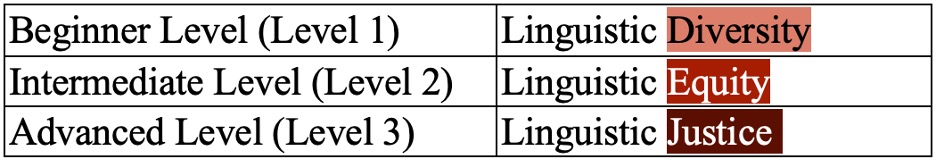

In this article, I synthesize some of the scholarship on antiracist writing pedagogy into three distinct claims that I see in that scholarship. I have labeled these three claims (1) Linguistic Diversity, (2) Linguistic Equity, and (3) Linguistic Justice. I used these three claims that I see in the scholarship to construct an outreach scheme in which each claim provides the content of one level in that scaffolded curriculum. As illustrated in Table 1, the beginner level is Diversity, the intermediate level is Equity, and the advanced level is Justice. For example, claims I see in scholarship that advocate for linguistic diversity are the claims used to inform the Linguistic Diversity level.

Table 1

Three Levels of Antiracist Scholarship and Practice

Level 1, the Beginner Level which I call “Linguistic Diversity,” teaches first that all languages and linguistic varieties are equal in their capacity for communicating accuracy and nuance. No language is better than any other language. Second, it teaches that language is inextricably tied to one’s identity, culture, and history.

Level 2, the Intermediate Level which I call “Linguistic Equity,” engages notions of power and privilege through an open discussion of systemic inequity, and this level attributes the prestige that some linguistic varieties enjoy to this systemic inequity.

Level 3, the Advanced Level which I call “Linguistic Justice,” contains three key claims: first, there is no such thing as Standard Written English (SWE) to begin with (it is actually white English) (Greenfield, 2011). Second, this level claims that code-meshing, not code-switching, should be the norm in academic spaces (Young, 2009). Finally, this level insists that all of this is a matter of justice (Baker-Bell, 2020), wellbeing (Green, 2018), and life or death (Inoue, 2019).

This scaffold raises some ethical concerns, as any scaffolding scheme around DEI work might, concerning who is speaking and how much they are heard no matter how appropriate the delivery is. Should we not just speak the hard truths without attenuating them for a where a particular audience might be in this scheme? This concern will be addressed later in this article in a discussion about utopianism and pragmatism in social movements.

Our Writing Center Context

The three levels I developed are the result of practice as much as research in writing center studies. The practice piece came from my work as the director of a writing center at a private SLAC (small liberal arts college) where approximately 30% of the student body identifies as students of color, and approximately 30% of its population is international students—many of whom are EAL (English as an Additional Language). At the time, our writing center staff consisted of around 25 undergraduate peer tutors, and me, the director.

The praxis from which the scaffold emerged was the antiracist initiative my staff and I undertook starting in 2020. Ten tutors formed the Social Justice Committee, and they were responsible for everything from decolonizing the contents of our center’s bookshelf to facilitating staff meeting discussions on antiracist readings2. To do this work, these tutors were equipped with antiracist concepts that they learned in our tutor education course—from the classic by Anzaldua (1987) “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” to work on translingualism (Horner et al., 2011), to work by Young (2009) on Black English and code-meshing.

It was the Social Justice Committee that was the engine of our antiracist outreach. I could not have undertaken this work without staff who were committed to social justice work and identified as students of color and EAL students. In this way, the racial and linguistic composition of the staff was key to carrying out antiracist outreach. Given this, we set about to ensure a staff composition equipped to carry out our antiracist work. A year into my directorship, my tutors and I were able to transform our recruitment and hiring practices in an antiracist direction, resulting in a much more diverse writing center staff—one that was 40% students of color, including three EAL/multilingual tutors.

The new recruitment process I employed minimized the formerly central role of faculty in the recruitment process, and instead centered tutors and tutor expertise. In this way, I worked more horizontally than vertically in the power structures of the university: instead of asking someone in a position of authority (like a professor) to recommend applicants, the tutors reached out (horizontally) to their peers for names of possible tutors. Instead of identifying candidates from faculty recommendations, for example, I reached out to student clubs that were racially diverse and committed to social justice. The tutors on staff helped me lead this charge: a tutor who was also a member of the Black student union on campus, for example, spoke at one of their meetings to describe what it was like to work at the writing center. I was not present at this meeting, and I think that is key to working horizontally by centering tutor expertise and ensuring tutor autonomy in the recruitment process.

I also relied on university staff to identify students who played important roles on campus to advance justice and equity outside the classroom. For example, I reached out to the community engagement office to get names of students who were passionate about changemaking work; in antiracist initiatives I conducted at other institutions, I reached out to the first generation student office and the TRIO office to recruit marginalized students; and my first stop, no matter what institution I work in, is always the diversity and equity office to learn of students whom these staff collaborate with on their DEI programming.

However, these collaborations did not mean cutting faculty out of the process altogether; painting faculty in a negative light is certainly a trope writing center directors should avoid. Some faculty did play a role in our recruitment process: I worked closely with faculty whom tutors identified as committed to social justice, and faculty who had significant inroads to communities of color and other marginalized groups on campus.

To inform the conversations in our outreach efforts, we knew we needed data on linguistic racism on campus. So we undertook a campus study on linguistic racism. In summer 2021, two tutors received an institutional grant for an IRB-approved study. As part of this study, these tutors conducted four focus groups and eight interviews to get a sense of how students of color, especially EAL students, at our university experienced and responded to linguistic racism. In a preliminary analysis, the data we collected suggested that BIPOC and EAL students on campus were experiencing significant linguistic racism on campus (in and out of classrooms), and in the town in which the university was located. Our hope in this study was that those stories would continue to fuel our antiracism initiative3.

Workplace justice was foundational to that writing center and structured all of our efforts; that is, whomever worked on the “shop floor,” as it is said in labor organizing circles, should control what happens on the shop floor. As I have written about elsewhere4, I believe in labor literacy being a part of tutor education; that is, tutors should be given a space to reflect on and learn about their workplace rights as part of any tutor education with a social justice emphasis. Workplace justice means that leadership should emerge from the rank and file, and workers should be paid for all forms of labor. For this reason, the work of the Social Justice Committee was always paid and tutor-led. The tutors on this committee would lead our weekly staff meetings, where the committee members would bring their ideas to the wider staff for the latter’s feedback and approval. In addition to this paid activism, tutors were paid an hourly wage to work on the aforementioned scholarship that emerged from our antiracist initiative (see conference presentations by Borden, Brouillet, Burns, Schnier, Toledo and Turner in the References).

At the same time, as tutor-centered and tutor-led as the Social Justice initiative was, I was responsible for any interfaces with faculty and other people in positions of institutional power. This is because I believe that, as a person in power myself—despite how powerless and institutionally marginalized writing center directors can feel at times—it was my responsibility to be on the “front lines.” This is especially true for me as a white writing center director supervising a staff of many tutors of color. I saw myself as working for the tutors, not them working for me. They kept me accountable, ever pushing me to do more faculty development work so that faculty could be part of the change the tutors hoped to see in the world. After all, the tutors were guiding the charge and designing the plans. I was there to support, provide resources—and represent the writing center to faculty.

Level 1: Linguistic Diversity

Key Claims

- All languages and linguistic varieties are equal in their capacity for communicating accuracy and nuance. No language is better than any other language.

- Language is inextricably tied to one’s identity, culture, and history.

The first level, Linguistic Diversity, is designed for an audience’s first brush with ideas about writing and racial identity. The central message of this level is that there are a lot of ways to communicate, and these ways are all equal in their capacity for communicating accuracy and nuance; no language is better than any other language. Although I think “difference” and “diversity” can be used interchangeably, I intentionally call this level in the scaffold linguistic diversity and not linguistic difference because I am attempting to echo the language of social and institutional DEI efforts which use the word diversity and not difference. Much more than the word difference, diversity is a word that is in the cultural zeitgeist right now. For example, see Figure 1, a photograph of the widely popular “Celebrate Diversity” bumper sticker.

This level emerged in the scaffold when, during interfaces with faculty, other staff, and administration, I found myself needing to slow down the conversation so that we eased into talk of linguistic antiracism. In these moments, I started to suspect that I needed to start with just the general idea of linguistic difference.

Figure 1

Celebrate Diversity Bumper Sticker

Note: Reprinted from @Portlandia n.d., Retrieved January 21, 2024 from https://giphy.com/gifs/portlandia-season-5-episode-7-l4Ep65WYRISNi9UAM

Exemplary of the claims at this level include John Russell Rickford (2000) in his work on Black English, Jennifer Jenkins’ (2015) work on World Englishes, and the highly influential NCTE (1974) statement “Students’ right to their own language” (SRTOL). One of the central claims of Rickford is that Black English is not slang; it is a rule-governed, systematic, complex language. Jenkins proves the same thing about varieties of English spoken around the world. And I believe that SRTOL spans two levels of my scheme—Diversity and Equity—but its central claim that all languages are equally legitimate belongs in this first category of Linguistic Diversity.

What kind of evidence can we use when working at the Linguistic Diversity level? Just as my work aims to center tutor voices and strengthen tutor agency, other student voices need to be centered as well. As we worked at the Linguistic Diversity level, student testimonials became a powerful resource. In my faculty development work in particular, I find that amplifying student voices through the testimonial genre (when the students’ identities are protected and their consent to disseminate the testimony is explicit, of course) provides faculty with the empirical data they require in order to understand that students have expertise—that students can teach faculty about concepts like linguistic diversity. In this way, students are not just on the receiving end of oppression; they create more antiracist futures by reporting on their own language practices.

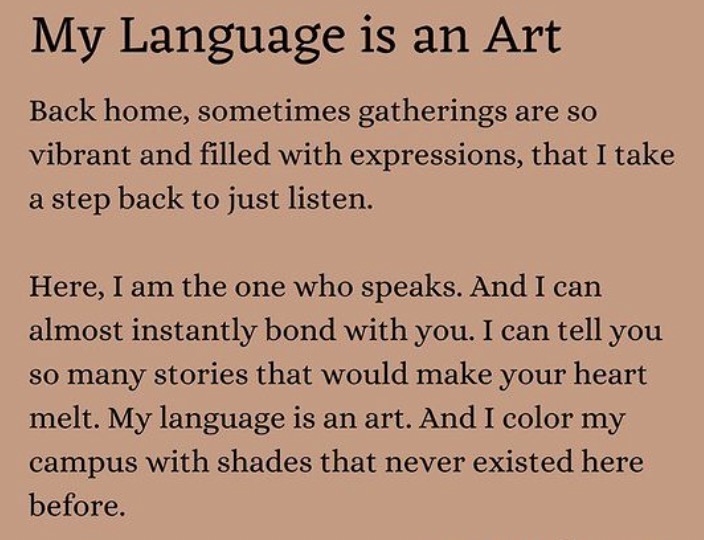

But where might we find these voices? They may already be around you (or you may have to support the effort to create that venue). At my institution, that venue was already there: an Instagram page, called “[Name of University] Speaks,” was formed to include anonymous testimonials from BIPOC and EAL students about the racial and/or linguistic discrimination that they have faced on campus. I’d like to highlight one of these testimonials because I think it exemplifies a key claim of Linguistic Diversity: this notion that there is more than one right way to speak and write, and minoritized linguistic varieties are as legitimate as any other linguistic variety. Figure 2 is one such post from that Instagram account.

Figure 2

My Language is an Art Instagram Post

Note: Reprinted from [Name of University] Speaks Instagram page. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

In this post, we see two key claims of the Linguistic Diversity level: first, the author makes a case for the equality of her language with other languages through the affective dimension of celebratory vocabulary to describe her home language, using words like “art” and “vibrant.” Second, the author situates these artful language practices within the author’s identity by using the opening phrase, “Back home.” The author also draws a connection between language and not just identity, but racial identity in particular when the author self-identifies in terms of racial diversity at the end of the post with the metaphors of “color” and “shades.” In this post, we see the two key claims of the scholarship on Linguistic Diversity come to life through personal testimony.

I project this anonymous Instagram post at faculty development workshops that argue for the value of linguistic diversity because it drives home the message that all languages are equal—and that because students already seem to know this, faculty should learn this fact too. This essential fact, I argue in this article, lays the foundation for the next level we can go to in our discussions with people inside and outside our writing center.

Level 2: Linguistic Equity

Key Claims

- Offers a critique: How did we get here? Through systemic inequity.

- Explicitly addresses why some linguistic varieties enjoy privilege and others are repressed.

Level 2, the Linguistic Equity level, follows up on the Linguistic Diversity level by reasoning that we may not see this equality among languages because some languages and linguistic varieties have, by design, more power and prestige than others. That is, the Linguistic Equity level explicitly addresses why some linguistic varieties enjoy prestige and others are repressed: because of systemic inequality—inequality by design.

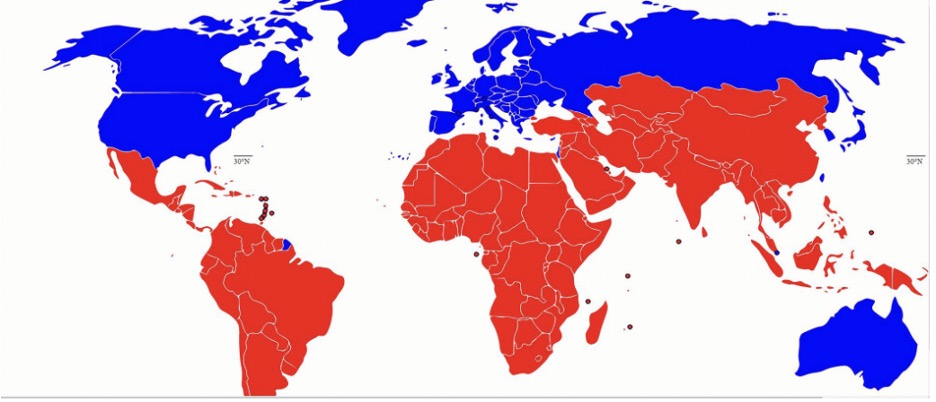

The Linguistic Equity level asks: why are some languages held in higher esteem than others? The explanation I offer here has to do with the political economy (i.e. how power flows) of language policy. From a global perspective, the unequal status conferred on different linguistic varieties is a consequence not of the value or worth of those varieties. Rather, this unequal status is rooted in political economy.

When we talk about political economy, some useful terms include the terms “Global North” (see blue land in the map in Figure 3) and “Global South” (see red land in the map in Figure 3). The idea behind these terms is that the distribution of wealth we see wherein countries in the north are typically rich and countries in the south are typically poor is not due to fortune, luck, or even natural resources; it is due to the Global North’s power over the Global South through the history of colonialism, capitalism, genocide, and land dispossession. In other words, these inequalities we see are the result of power, not chance. They are by design.

This notion of power is central to the key claim of the Linguistic Equity level.

Figure 3

The Global North and the Global South

Note: Reprinted from Braff, L. & Nelson, K. (2022), “The global North: Introducing the region” in K. Nelson & N.T. Fernandez (Eds.), Gendered lives: Global issues. SUNY Press. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/genderedlives/chapter/chapter-15-the-global-north-introducing-the-region/

Level 2 applies this logic of political economy to language policy by holding that it is not the inherent value of the linguistic variety that determines that variety’s elevated status; rather, it is the prestige conferred onto certain linguistic varieties that determines status. In other words, it is all about who has power, and what they do with it.

Which claims in the field of Writing Studies exemplify this second level? I believe we can find Equity claims in the work of education scholar Delpit (1995) on code-switching, literary scholar Spack (2002) on indigenous languages in the U.S., linguist Lippi-Green (1997), and Shapiro (2022) in her work on Critical Language Awareness.

A key example of scholarship that provides the content of this level is work by Lippi-Green (1995). Lippi-Green helpfully theorizes what she calls “standard language ideology,” recognizing that SWE is enforced because of hegemony rather than some inherent superiority of SWE. These scholars’ claims emphasize the role of power and privilege, hence their utility when we are teaching at the level of Linguistic Equity.

Some scholars I place at the Equity level make claims that bleed into the Justice level, some just plant the seeds for the Justice level, and some make claims that actually contradict claims in the Justice level. As an example of the scholarship that works at the Equity level to plant seeds for the Justice level, Spack (2002) chronicles how genocide is responsible for the erasure of indigenous languages in the U.S. In the way, she points to power and privilege (hallmarks of the Equity level). However, it is outside the scope of her study to highlight what role indigenous resistance and institution-building played and still play in the Native American Language Reclamation movement5. As an outcome of social justice movements, institution-building belongs to the Justice level. Level 2 is about recognizing power and privilege; as I will discuss in the next section, Level 3 is about creating alternative structures of power.

On the other hand, some claims in some scholarship that I include at this level, Equity, in fact ultimately contradict the claims of Level 3, Justice. For example, Delpit (1995) believes that while it is true that Black English is unfairly denigrated because of social inequality, she ultimately argues that Black students must code-switch in order to survive in educational and professional settings. Young (2009), a scholar whom I identify with the Justice level, helpfully critiques this position.

To illustrate how I started at Level 2 with staff professional development, I will give the example of a workshop I did for the Admissions Office on linguistic antiracism. After a public presentation that the tutors gave on our writing center’s antiracist initiative to the university, the head of the Admissions Office approached me to ask if I’d give a workshop on linguistic antiracism to her staff so that they would read the incoming applications for first-year classes through an antiracist lens.

What I know about my audience there—admissions counselors—is that they are tasked with creating a diverse incoming first-year class. At the same time, they sometimes work under the very common assumption that any deviation from the norms of SWE in a paper is categorically an error. Taking stock of these two observations, I started at Level 2 with this audience, the Linguistic Equity level. I did not start with Level 1; after all, this group already valued diversity.

During the workshop, I indeed discovered that this group valued diversity. However, they struggled over how to think about—and ultimately rate—essays displaying linguistic diversity. They worried over written accents and linguistic varieties that people in power consider incorrect or non-standard. The admissions counselors asked: should we penalize essays with such usage? Shouldn’t these multilingual and multidialectal students know how to code-switch and write “correctly” for an application essay?

In my Level 2 mindset, I asked them: And who gets to determine what standard English should be? Professors, they replied. (The implication there being: professors at this university who will look down on the Admissions office for admitting students who “can’t write!”) To which I replied, “No, you are determining what counts as correct English. Right here in this room. You are gate-keepers, just as much as professors are, as much as I am. Take your responsibility seriously. You have that power. Use it to put your money where your mouth is with diversity.” In this way, the claims of Linguistic Equity aided me in making the argument that there’s a reason why some linguistic varieties are valued over others, and that the reason is determined by those in power. Moreover, if that is true, more people have the power to change the status quo than we might initially think. In this moment, I was merely echoing the mic-drop moment at the conclusion of SRTOL (1974): “English teachers who feel they are bound to accommodate the linguistic prejudices of current employers perpetuate a system that is unfair to both students who have job skills and to the employers who need them” (p. 21). In other words, people in power (in this case, writing professors and admissions counselors) need to own the power they have to not be a part of the system of linguistic inequity.

After this exchange, I stayed with Level 2 logic by sustaining the conversation about what power and privilege have to do with linguistic diversity. In particular, I focused on power structures in the university that prevent us from valuing all languages equally. I invited a conversation with these fellow staff members about how we feel as staff when our work is judged out of context by our colleagues who are faculty, and I suggested that we cope with the faculty-staff cultural divide that we commonly see by offering to have conversations with faculty about our work and why we do what we do. We can show to faculty our rating rubrics for those application essays, and the Admissions office could collaborate with me to provide to faculty a bibliography of writing pedagogy research that defends their equitable rating practices. Ultimately, I encouraged the staff to consider Level 2 insights by revising their rating rubric to not penalize essays written with an accent or in a different linguistic variety, and to count me as an ally when it came time to stand by that rubric.

At this point, I did not feel that Level 3 logic would have landed—that is, I was not sure that the Admissions staff would have received well my message about how SWE is itself a form of white supremacy. It seemed important to stay with the conversation about institutional power—for now—because the political economy of the university seemed to be a pain point for them in adopting Level 2 insights. However, I would argue that there is certainly room for that Level 3 conversation—at the right moment.

Level 3: Linguistic Justice

Key Claims

- There is no such thing as SWE to begin with (it is actually white English) (Greenfield, 2011)

- Code-meshing, not code-switching, should be the norm in academic spaces (Young, 2009)

- All of this is a matter of:

- justice (Baker-Bell, 2020)

- wellbeing (Green, 2018)

- life or death (Inoue, 2019)

I call Level 3 “Linguistic Justice.” Linguistic Justice is a term used by many scholars who have forwarded claims that populate this level in the scaffold.

Importantly, the Linguistic Justice level:

- Emphasizes revolutionary praxis in and out of schooling

- Offers a vision of what is possible; imagines new futures

- Is both utopian and pragmatic

- Bears connection to social movements

- Incorporates claims at the other Levels of this scaffold into this revolutionary space

Figure 4

Chicano Park Mural

![Painting of a group of people gathered with a flag that reads, “La Tierra Mia… Chicano Park” [translation into English: My Land…. Chicano Park”] and another flag that reads “SI SE PUEDE” [translation to English: “It is possible”].](http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/figure-4.jpg)

Note: Reprinted from Department of Ethnic Studies, “Chicano Park 2015 Murals Documentation Project: Guide to the Murals of Chicano Park” (2015). Ethnic Studies Books. https://digital.sandiego.edu/ethn-books/1. Mural created by Toltecas en Aztlán, S. Barajas, G. Aranda, A. Román, V. Ochoa, J. Cervantes, G. Rosette, G. M. Lujan, D. Reyes, & M.E.Ch.A. (1973). San Diego, CA, United States.

The mural you see in Figure 4 is part of a larger mural created by artists Toltecas en Aztlán, Salvador Barajas, Guillermo Aranda, Arturo Román, Victor Ochoa, José Cervantes, Guillermo Rosette, Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, Daniel de Los Reyes and M.E.Ch.A. to support the people-led occupation of a Chicano neighborhood in San Diego. The purpose of the occupation was to prevent the demolition of the neighborhood for the construction of a highway. The occupation led to the successful community-led development of “Chicano Park” in 1973. Of all the social movements I could highlight as a model for how we might imagine our own antiracist work, the 1973 movement for Chicano Park comes to mind because of how integral Chicano Spanish was to the movement, as illustrated in a San Diego mural which portrays signs with this particular linguistic variety.

I use this particular movement also because it presents both a utopian and pragmatic road to liberation. By utopian I mean dreaming big no matter what the chances are of your dream becoming a reality. By pragmatic I mean framing liberation as the art of the possible by valuing strategy. When we assume that the audience for these murals was not just Spanish-speakers, we might conclude that, by using Chicano Spanish, the artifacts of this movement (like the mural in Figure 4) could be called utopian because the artists did not limit their strategy based on what might be most effective with a non-Spanish-speaking audience. These muralists refused to be limited by narrow notions of what is possible, and what might be most strategically effective. In this way, the movement, at least according to the artifact in Figure 4, could be called utopian.

On the other hand, the movement is deeply pragmatic in the sense that the actions of the Chicano movement mirrored other movements across the U.S. that aimed to prevent highway construction through non-white neighborhoods. In this way, Chicano activists knew what was possible, and dreamed within the possible.

I believe that effective movements need utopianism as much as they need pragmatism. What might be the equivalent of a utopian vision in writing pedagogy? Instead of moving incrementally toward liberation, we might imagine the bold work of creating a wholesale curriculum, for example, that teaches linguistic power to youth—regardless of the pragmatic consideration of whether or not that curriculum is likely to be replicated across the U.S.

Baker-Bell (2020) does just that. Baker-Bell studied a group of Black high school students in her native Detroit for how they view Black English. She uncovers their deep-seated hatred of their own linguistic variety, which she calls ABLR (anti-Black linguistic racism). In the book, she describes a curriculum she created to teach students that a) Black language is systematic and rule-governed, as opposed to street slang b) racism is the reason it has not been taught as such and c) you don’t need to code-switch in order to survive.

This third claim is what I think of as Justice because, in my schematic, the Justice level offers the most progressive and radical vision, and the one I strive for in my writing center work (but often fail at doing so, as I discuss in a later section). I see this level as the most radical and progressive for three reasons: first, this level calls for action: it is a solution-based vision. Baker-Bell created a concrete curriculum; the Chicano movement in San Diego created concrete social change. Second, it presents not just a call to action, but a call to action directed by the imagination of a new future so foundational to social movements. That is, the picture of what we want and need may be blurry because it may not exist in the world yet. However, as labor and civil rights organizer Myles Horton says, “we make the road by walking.” For these reasons, I am using more social movements than academic scholarship as examples of this level because I believe that social movements, like the Chicano movement, indeed offer the kind of more progressive and radical ideology that scholars like Baker-Bell also offer.

So, who on my campus was ready to hear Baker-Bell? The peer tutors, of course! I’ll highlight one such peer tutor in particular. Toledo, in his 2021 International Writing Center Association paper “Critical Consciousness in the Linguistically Just Tutorial,” asks the question: yes, language is about justice—but how do I enact linguistic justice in the nitty-gritty of an actual tutorial? He paraphrases his International Writing Center Association paper like this: “Say to the tutee: ‘These are the rules, but they are bullshit. Take em or leave em. If you want to talk about how they’re bullshit, I’m game6.’”

Because of the power, agency, and subjectivity that the peer tutors in our writing center practiced in the operations of the writing center—especially in the work of the Social Justice Committee—they were able to “be the change” they wanted to see on campus by having conversations about linguistic justice with each other, with their non-writing center peers—and with their tutees.

Learning From Failure

I will leave this description of the levels with a scenario of when scaffolding was not in place—to everyone’s detriment. A member of a STEM department who had been doing some antiracism work in her department reached out to me to invite me to a department meeting because she heard I had some antiracist initiatives going, and she wanted to join forces. I was game. I came with material about Linguistic Diversity and Linguistic Equity, the first two levels, so I was ready to talk to these STEM faculty about how marginalized linguistic varieties are as legitimate as the linguistic varieties they use in STEM. If they seemed to accept this claim, I’d then broach the notion that STEM is an exclusionary language, and that the reason it is held in high regard is because of who gets to be an authority and who does not.

But the faculty member who invited me got ahead of this and said, “Our department is racist as long as it requires papers to be written in the language of our discipline.” I was then dismayed to see her colleagues disparage her remarks and facetiously suggest that we no longer require lab reports but choreograph interpretive dances instead. That felt like a fail. I didn’t know how to recuperate the discussion because I hadn’t planned ahead with this faculty member on how we would proceed in that department meeting. This was a lesson I learned about the art of collaboration so central to writing center work.

The question remains, however: in our collaboration, what level would I have recommended we start with her departmental colleagues? In preparation for the department meeting, I could have discussed with this faculty member what her own beliefs were around linguistic diversity, equity, and justice. We could then strategize at which level to start with her colleagues in that meeting. If we were to start at Level 1 (Linguistic Diversity) for example, I would ask her if I could bring evidence from WAC scholarship that demonstrates how many STEM publications are written in an accent. Then, in the meeting, we could have workshopped some of these examples from a translingualism lens to illustrate how written accents in published STEM writing are negotiated similarly to how oral accents are—that is, meaning in STEM publications is negotiated effectively. Instead of jumping to level 3, Justice, by locating STEM writing standards as racist, we could have started at level 2, Equity, by discussing who sets these standards and how these standards exclude many STEM writers and would-be STEM writers. Whether or not we had strategized to start at Level 1 or at Level 2, planning ahead more could have ensured that we didn’t get so far ahead of ourselves that we would lose our audience as we did.

The Ethics of a Scaffold

All this scaffolding raises the question that should intrigue and often confounds every rhetorician: should speakers care about what people are willing to hear or just say what needs to be said? I believe that these two options are not the same because what a writer wants to convey and what a reader needs in order to concur with the writer are often opposed. When we graft this classic question at the heart of rhetoric onto the landscape of antiracist work with tutors, other students, faculty, staff, administration, or the wider community—especially if they are new to or skeptical of antiracist work—this question takes on a political dimension that involves white power and privilege, white fragility, and the potential of centering white comfort in these tough conversations about race. Speaking for myself, perhaps there is a way in which I, as a white person, have the luxury of a scaffold because I’m not the target of racist harm—is it that because I am removed from the danger of racism, I can justify the development of an elaborate scheme to ease myself and other white people into the work of linguistic justice?

In my antiracist community work, there is a framework that has helped me understand why scaffolding is not just an effective way to do social justice work, but one that is responsive to how humans develop psychologically. I speak of “racial identity development.” This framework, developed by psychologist Helms (1993), began as a way of understanding how white people in particular can evolve into antiracists. (Later, she collaborated with other researchers to develop a theory of how other racial groups develop their racial identities and racial consciousness).

What I will introduce here is specifically for the white people to whom I present linguistic racism. Of course, that said, it is not always the case that the only skeptics of linguistic justice work are white people: I find in both my community work and my writing center work that members of any racial identity group can be just as skeptical about radical liberation politics as so many white people are.

Based on hundreds of counseling sessions with psychological clients from across racial categories, Helms (1993) proposes that white people pass through six stages of development as they develop their identities toward becoming antiracist (which is what Helms calls the ultimate “Autonomy” stage). The first stage, “Contact,” is where a white person has their first brush with acknowledgement of race and racial difference (not racism, however—that comes later). I would say that white people in this first phase of racial identity work might respond best to the Diversity side of the linguistic racism scaffold because both acknowledge difference and even celebrate it, but don’t go as far as acknowledging inequity. In this way, we see how the categories that Helms lays out make a scaffold necessary—to respond specifically to whatever phase of development our white audience is in.

The second phase in Helms’ scheme for white people’s racial identity development is what she calls “Disintegration.” This is white people’s first brush with the reality of racism, and white people in this phase find themselves in conflict over their own part in the reality of racism. I would argue that a white person in this phase is likely to be very receptive to Level 2 of the scaffold, Linguistic Equity, because this audience is at least clued into notions of power and privilege.

However, what is so resonant about Helms’ theory is that the phases of development are far from linear. White people take two steps forward and one step back with every phase. We see that in her next step of racial identity development: stage 3, “Reintegration.” In this phase, white people who were on the cusp of change and growth in the “Disintegration” phase backslide into reactionary thought patterns that work to justify their privileged social position.

I find a great many white faculty and staff who seem to be in the Disintegration phase. In this case, I find that introducing such an audience to the last phase of the scaffold (Linguistic Justice) would just inspire more backlash. Take, for example, comments like this one from white faculty at antiracist faculty development workshops I’ve led (a composite paraphrase of such moments): “Everyone has a cross to bear, as do I. I don’t whine about it or go start a movement about it. I learn to cope. I play the game. Why can’t this generation [gloss for: students I don’t understand] learn to do the same?”

On the one hand, in those tense moments, I could take them back to the first phase, Linguistic Diversity, and argue for valuing diversity. However, I hesitate to do that because this audience bears indicators of Helms’ third phase, Reintegration, where they are working hard to justify the status quo of racism. On the one hand, to take them back a step on the scaffold to arguing for valuing diversity might inspire further backlash; on the other hand, to attempt to plow through to the third phase, Linguistic Justice, would risk alienating them further. Rather, it is important that—once we see signs of Reintegration in this audience—we stay with the claims and evidence of the second phase, Linguistic Equity, and work within it together, really grapple with these claims and the evidence.

Interestingly, according to Helms, the next stage, Stage 4: Pseudo-Independence (part of a group of phases that move toward a personal commitment to antiracism), can be achieved only through an event that jolts the white person into the next phase. The jolt, as opposed to a sustained cerebral reasoning process, is an experience that creates such dissonance with the white person’s justification of the status quo that they can no longer sustain their Stage 3 views. The white person in this phase often has to “see” or “hear” blatant racism for themselves; they have to have (what counts to them as) “hard evidence” from a trusted source. For example, a white person may be most convinced of the existence of racism while reviewing a video of police brutality toward a Black teenager; a friend of color may testify to being called a racial slur that week; a student relays in that white professor’s office a racist incident she experienced in the dorm.

But unless a white faculty member in our faculty development workshops reports a good friend being called a racial slur that week, faculty development facilitators must create those jolting moments—or at least prime our white audience for the time when they should experience such moments. Student testimonials to the racism that they experience on campus have the power to be that jolt. Figure 5 is another testimonial from the aforementioned Instagram page that can provide that empirical evidence that many reactionary skeptics need in order to move through Helms’ phases.

Figure 5

Trump Rally

![On green background, the Instagram post reads: Let’s get the trump rally going. Freshman year, three friends and I were sitting at the [dining hall] booths. Like many [university] students, once we have dinner, we usually stay long just to talk. Being Spanish speaking Latinas, we’re having our conversation in Spanish. At the table next to us were a few white guys, and all of the sudden my friend notices one of them looking at us and say “Let’s get the trump rally going.” Our reaction was to speak louder. Their comment might have flew past them, but three years later we still remember it.](http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/image2.png)

Note: Reprinted from [Name of University] Speaks Instagram page. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

But we also need to be deeply skeptical of any sanguine insistence that the only way to move past the Disintegration phase is to essentially exploit BIPOC trauma to extract lessons that will aid in the racial enlightenment of white people. First, as previously suggested, the fact that white people need “hard evidence” (or what to them seems to—subjectively—add up to that) in the first place should invite our deep scrutiny, as it is a common deflection tactic used to deny the existence of racism. But perhaps more problematic is the fact that this evidence sometimes takes the form of testimonies about BIPOC trauma, like the ones we see on the aforementioned Instagram page where students of this university posted their stories of the linguistic racism they experienced. This ethical conundrum goes back to the utopian vs. pragmatic question I raised earlier: is it better to do what we think will be most effective, even if you have to hold your nose as you do so? I do not have an answer to this question, except to make sure that the testimonies one might use are ones that students have already released to the public in such a way that we do not doubt they want their voices to be amplified; consent must be the bare minimum in this ethical dilemma. Certainly the issue of how to think about the ethical use of the power of testimonies about BIPOC trauma bears further research.

If we take the pragmatic view, the more we know about how humans develop psychologically, the more we can scaffold to where white skeptics might be at that moment. That said, this is much easier to do in one-on-one conversations, of course, as opposed to large groups where, inevitably, white audience members are in very different stages of racial identity work. In the case of group workshops, however, white faculty who are further along in their antiracist development can also provide the necessary jolt by persuasively bringing in such powerful empirical data. This is why faculty development requires superb listening skills on the part of the facilitators so that we as facilitators know when to move back and let the participants educate each other.

The Long Road We’re On

I hope what I’ve presented here testifies to three points that have emerged from my writing center research and from my writing center practice toward antiracism: first, that we might consider being pragmatic in our antiracist work, even when we are forwarding a utopian vision; second, that we must consider the ethics of a more pragmatic strategy; and finally, that no one is the object of our work—writing center practitioners must honor the subjectivity of all players by collaborating closely with fellow tutors and with faculty, staff, and other institutional stakeholders. I encourage you to ask yourself: who on your campus is at which level, who seems most ripe to move to the next level, and what opportunities might you help put in place to move us all toward a more antiracist future?

As a final note, we cannot expect perfection in liberatory work—in the context of our communities or within higher education. The work is hard and the road is long and, as Helms teaches us, far from linear. But, again, I am reminded of the words of antiracist organizer Horton that we make the road by walking it. I imagine the scaffold I’ve presented here as that long, twisted, recursive road wherein whomever we meet along the way has a part to play in the struggle.

Notes

- [1]However, I do hesitate to collapse these two categories (of those “new” to antiracism and those who are “skeptical” of antiracism) because it puts us in danger of equating lack of exposure (newness) with innocence. Instead, I would contend that “newness” to the reality of racism and the concept of antiracism is a privilege that results from white supremacy itself, which masks racism. For example, when white people claim that they don’t know much about race not because they’re at fault for that, but rather because they have not been exposed to people of color, we must point out to them that it is not a matter of accident that they grew up, went to school, and work in all-white spaces; rather, it is white supremacist policies such as redlining, public defunding of public schools, and discriminatory hiring practices that have constructed this racist reality—and benefitted white people. White people’s newness/lack of exposure to these conversations about race is indeed a consequence of policies that have in the end benefitted white people. White people, in this way, cannot claim innocence. As I make my case for how to reach both those new to or skeptical of antiracism, I urge us to keep in mind how both the skeptics and the newbies must be held equally accountable for their views and for their actions—because innocence is itself a product of white supremacy.

- [2] The mission and evolution of the Social Justice committee is documented in a conference paper: Brouillet, G., Schnier, A. & Burns, E. (2021, November 12). Achieving Anti-racism: How tutors can be engines of social justice in higher education [Conference presentation]. National Conference on Peer Tutoring in Writing, Online.

- [3] Preliminary data analysis is available in a conference presentation: Pawlowski, L. (2024, April 6). Building a more just future: BIPOC students respond to linguistic racism [Conference presentation]. Conference on College Composition and Communication. Spokane, WA, United States.

- [4] See chapter, Pawlowski, L. “Exposing Exploitation: Myths in Writing Center Supervision,” in the forthcoming book The Reluctant Supervisor: Recognizing and Rethinking Power in Writing Center Supervisory Practices (Eds. Azima, R.; Levin, K.; Steck, M.; Tang, J.K.).

- [5] One recent work that highlights some of this movement-building and institution-building in linguistic preservation is Ross Perlin’s (2024) Language city: The fight to preserve endangered mother tongues in New York (Grove Atlantic Press). In the book, he chronicles the work of the Endangered Language Alliance.

- [6] For the full argument, see Toledo, A. (2021, October 20). Critical consciousness in the linguistically just tutorial [Conference presentation]. International Writing Centers Association 2021 Conference, Online.

References

Anzaldua, G. (1987). How to tame a wild tongue. In Borderlands la frontera: The new Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Braff, L., & Nelson, K. (2022). The global North: Introducing the region. In K. Nelson & N.T. Fernandez (Eds.), Gendered lives: Global issues. SUNY Press. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/genderedlives/

Brouillet, G., Schnier, A., & Burns, E. (2021, November 12). Achieving Anti-racism: How tutors can be engines of social justice in higher education [Conference presentation]. National Conference on Peer Tutoring in Writing, Online.

Delpit, L. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom (1995). W.W. Norton & Co.

Green, N.-A. (2018). Moving beyond Alright: And the Emotional Toll of This, My Life Matters Too, in the Writing Center Work. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15–34. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26537361

Greenfield, L. (2011). The “standard English” fairy tale: A rhetorical analysis of racist pedagogies and commonplace assumptions about language diversity. In L. Greenfield, & K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable action and change, (pp. 33-60). UP Colorado.

Helms, J. E. (1993). Black and white racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Praeger.

Horner, B., Lu, M.-Z., Royster, J. J., & Trimbur, J. (2011). Opinion: Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English, 73(3), 303-321. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1065&context=faculty

Horton, M. & Freire, P. (1990). We make the road by walking: Conversations on education and social change. Bell, B., Fabenta, J., & Peters, J. (Eds.). Temple University Press.

Inoue, A.B. (2019). How do we language so people stop killing each other, or what do we do about white language supremacy. College Composition and Communication, 71(2), 352-369.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Global Englishes: A resource book for students. (3rd Ed.) Routledge.

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology and discrimination in the United States. Routledge.

NCTE, Committee on College Composition and Communication Language Statement Committee. (1974). Students’ right to their own language. College Composition and Communication 25(3), 1-32.

Pawlowski, L., T. Borden, & Toledo, A. (2021, October 9). Responding to Greenfield’s call to radicalize the writing center [Conference presentation]. International Writing Centers Association Conference, Online.

Rickford, J. R. & Rickford, R. J. (2000). Spoken soul: The story of Black English. Wiley.

Shapiro, S. (2022). Cultivating critical language awareness in the writing classroom. Routledge.

Spack, R. (2002). America’s second tongue: American Indian education and the ownership of English, 1860-1900. University of Nebraska Press.

Toledo, A. (2021, October 20). Critical consciousness in the linguistically just tutorial [Conference presentation]. International Writing Centers Association 2021 Conference, Online.

Toltecas en Aztlán, S. Barajas, G. Aranda, A. Román, V. Ochoa, J. Cervantes, G. Rosette, G. M. Lujan, D. Reyes, & M.E.Ch.A. (1973). Historical Mural [Mural]. San Diego, CA, United States.

Turner, C. (2021, November 12). Linguistic antiracism in STEM writing [Conference presentation]. National Conference on Peer Tutoring in Writing, Online.

Young, V. A. (2009). “Nah, we straight:” An argument against code switching. JAC, 29(1-2), 49-76.