Erin Green, University of Maryland College Park

Abstract

Because many graduate students have never visited a writing center and because Black language has historically been devalued in academic and professional writing, this article reflects on the nuances of working as a Black queer graduate writing center worker and my community-engaged literacy work of enacting linguistic justice in community writing spaces. This article also describes my own experiences as a Black queer graduate student navigating a white academy that is resistant to Black language and literacy practices. Lastly, I describe my process of designing and circulating linguistic justice posters in community spaces meant for writing to affirm the languages and literacies of Black graduate writers. With the combined community literacy work described in this article and my reflection on Black graduate writing center work, this article advocates for the affirmation Black graduate writers’ linguistic diversity and the community literacy work necessary to support them.

Keywords: Linguistic Justice, Reflection, Community Literacies, Black Language, Graduate Writing Centers, White Linguistic Supremacy

I visited my first writing center in my first year of college. At the time I was reapplying to keep all the scholarships that I had earned and applying for more scholarships so that I could take out less money in student loans. In retrospect, I’m glad that I did due to the several concerted efforts of right-wing policymakers and judges to ensure that only specific (i.e., white, straight, cisgender, male, able-bodied, and rich) populations can attend college. Only a few days after writing this, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decided to gut Affirmative Action, which allowed race-conscious admissions at colleges and universities (Totenberg, 2023). Later that week, SCOTUS decided to reject President Joe Biden’s plan to relieve student loan debt (Turner, 2023). About a month later, Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, revealed a history curriculum arguing that enslaved people benefited from the skills they learned while enduring chattel slavery (Luna, 2023). The discursive realities around race, racism, and education are moments rhetoric, literacy, and writing studies can learn from and respond to. Specifically, our field can interrogate how sociopolitical attitudes can influence material conditions in education. Within rhetoric and composition, writing centers remain for many, one of the very last stops before submitting their scholarship essays, cover letters, personal statements, writing samples, or any other kind of application materials. For many, writing centers are the last stop before submitting their final papers which determines whether they pass their course; thus, writing centers play an important part in determining the material conditions for many students.

If essays gon’ be the determining factor on if someone can attend college, or for many such as myself, if they can even afford college, then writing will be at the forefront for consideration of higher education access and opportunity. One way writing has been historically assessed has been through the writer’s language. As a Black queer writing center worker, my Black language has been either ignored or devalued (Faison, 2018). Because many graduate students have never visited a writing center and because Black language has historically been devalued in academic and professional writing, this article reflects on the nuances of working as a Black queer graduate writing center worker and my community-engaged literacy work of enacting linguistic justice in writing spaces. I argue that much of the work that some Black queer writing center workers do to enact linguistic justice is community work: work that happens outside the center. With some storytelling—cuz Black folks always got a story (Smitherman, 1977)—I describe my own experiences as a Black queer graduate student navigating a white academy that is resistant to Black language and literacy practices. In this essay, I also describe my writing center work with clients who were either Black or didn’t speak English as a first language. Last, I explain the community-oriented practices around creating and distributing posters for linguistic justice, and the implications of such advocacy.

To enact linguistic justice in the community, this article describes my process of designing and circulating posters in community spaces meant for writing. These posters include information about Black language, linguistic justice, and language politics. My goal for this poster project is for graduate writers of color, especially Black writers, to see and feel affirmed in their linguistic and language choices. This project works toward this goal by intentionally placing these posters in spaces where graduate writers of color are writing, reading, studying, tutoring, or doing any kind of literacy work. Additionally, the posters I created should prompt non-graduate writers of color to reflect on language politics and white linguistic hegemony. Lastly, by reiterating the connectedness of anti-Black violence happening on campuses and in classrooms with the anti-Black violence happening in the streets (Baker-Bell, 2020; Johnson, 2018), this project broadens its scope of reaching audiences outside of rhetoric and composition and academia (Greenfield, 2019). As our educational spaces become more and more anti-Black (e.g., banning race-conscious admissions, whitewashing Black history, and exacerbating racial capitalism via student loans), our field must not only respond to institutions’ restrictions on how Black folks are writing, but also on what Black folks are writing.

Gleaning a Black Linguistic Consciousness in a White Academy

So, when me and my scholarship essay entered my undergraduate university’s writing center for the first time (shoutout to the Harbert Writing Center!), I was prepared for someone to check my grammar, check my spelling, and essentially tell me if my essay was “good enough”: all the thangs writing center scholars and professionals have debated when discussing the purpose of a writing center. Even though I had never been in a writing center consultation before, I had my mama read over all my papers in high school and my first year of college. I went to the writing center because, for me, this was a matter of being able to afford staying at my university. I didn’t have the language in undergraduate, or Black Linguistic Consciousness (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020; Baker-Bell, 2020), to understand why I felt I needed to write a certain way. What I did know was that the people reading my scholarship essay were most likely going to be white people who spoke and wrote White Mainstream English (Baker-Bell, 2020). I didn’t have the language to know that what I was intending to accomplish was code-switching, but I knew I needed to do it to get the scholarship, and thankfully I was able to get the scholarship.

As I reflect on that scholarship essay, I find it ironic that the prompt requested me to define what outstanding achievement meant to me as an English major and to describe how I had demonstrated outstanding achievement in the English department at my university. I find it ironic because the research around Black language during this time, approximately 2016, was abundantly clear, yet I, a Black queer English major, was unaware it even existed. I was unaware of the decades of scholarship by my people who affirmed Black language as a legitimate language and also advocated against the very politics that sought to silence our language (Fisher, 2009; Gilyard, 1996; Kynard, 2013; Logan, 2008; Richardson, 2002; Royster, 2000; Smitherman, 1977; Young, 2007). I was completely unaware of the fact that the very reason I was going to the writing center had been an ongoing scholarly conversation. I had no idea that while I was trying to code-switch, English educators had written a resolution informing students that we had a right to write and speak the way we did at home (Committee on CCCC Language Statement, 1974). Now I think about how differently my essay would have been had I been aware of the scholarship on Black language and the politics of linguistic diversity. Would I have still written in White Mainstream English (WME) about how there was a literacy crisis in America’s colleges? Would I have still bragged about my analytical skills for interpreting literary texts in addition to knowing how to write in correct grammar, aka WME? Would I have still gone to the writing center asking for help with my grammar? Or would I have challenged the very language politics that I knew was happening with the committee of people reading my scholarship essay? And if so, would my Black Linguistic Consciousness have been seen as an outstanding achievement in English studies, or would I have just been written off as some Black kid who didn’t know how to use spell check?

In 2018, about two years after I got that scholarship, I joined my university’s writing center as a writing consultant. Again, an assessment of my writing was needed to determine my approval to work in the writing center. And again, I asked people around me to check my grammar and proofread my writing sample and my cover letter. I assumed the purpose of a writing center was to help students conform to WME, and for my entire time working at that writing center, that is what I did. I learned the basics of working in a writing center while still encouraging WME: nondirective tutoring, code-switching, and high-order concerns in revision. Until I graduated college in 2020, I provided nondirective tutoring void of a Black Linguistic Consciousness. It wasn’t til my summer preparing for graduate education in rhetoric and writing studies that I learned about the violence of forcing your language and literacy on somebody else (Stuckey, 1990). Once I was in graduate school and started working in my department’s undergraduate writing center, and later the graduate school’s writing center (GWC) I began to enact linguistic justice.

Disrupting Linguistic Racism in Writing Centers

April Baker-Bell (2020) defines linguistic justice as “an antiracist approach to language and literacy education. It is about dismantling Anti-Black Linguistic Racism and white linguistic hegemony and supremacy in classrooms and in the world” (p. 7). My journey of teaching writing center clients about white linguistic hegemony began with tutoring clients whose first language was something other than English. I, like many writing center workers, tutored international students who were often concerned about their spelling and grammar. When non-native English speakers asked for assistance with their grammar, I decided not to choose between a directive or nondirective approach. I wanted to avoid the binary-oriented approach to writing center tutoring that I had become accustomed to. Radical Writing Center Praxis offers the same line of questioning concerning the decision to think of tutoring as a binary (Greenfield, 2019). I saw affordances and limitations to both directive and nondirective tutoring, so I opted for a combination of both. I first provided a nondirective approach by asking my clients questions I felt would edge them towards a critical reflection of language politics in academic writing: Why are you concerned about grammar? What have you been told about “correct grammar?” Where do you think your “grammar” can be improved? Do you think your “incorrect grammar” distracts from the main arguments in your essay? After that, I opted for an approach that could be argued as a middle ground between directive and nondirective. I made it explicitly known to my clients that there was nothing wrong or incorrect about the way they spoke or wrote. I told them that the issue was not their “inability to write with correct grammar,” but that the issue was that academic writing privileges a particular kind of writing—White Mainstream English. I always ended this moment with “I’m happy to show you areas for improvement regarding your grammar but do know that I can still clearly understand your argument, your evidence, and your analyses.” I attempted to disrupt a common belief of the writing center, what Anna Treviño calls “a site of hegemony, of Standard English, of product-centered and current-traditional rhetoric” (Faison & Treviño, 2017, para. 7). After ensuring they understood my claims, I assisted them with grammatical and mechanical concerns in their essays.

I worked in an undergraduate writing center for my first year of graduate school. A year later, I became a fellow for my university’s GWC. Like Alexandria Lockett’s description of her GWC, mine also was a small office space, almost hidden (Lockett, 2019). My university’s GWC was in an office on the second floor of my library. There were about four to five desks for fellows and our clients to sit at and have our consultations. Most of the writing fellows preferred to have online consultations. The GWC’s training consisted of a few days where we were instructed to read scholarship from the fields of writing center studies, composition theory, and Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC)/Writing in the Disciplines (WID) (Blau et al., 2002; Hyland, 2008; Mackiewicz & Thompson, 2014). Our emphasis was on WID work as we would primarily be working with other graduate students who needed assistance with their thesis papers, dissertation chapters, and journal articles. With only about 20 writing fellows serving about 11,000 graduate students across 230 graduate programs (The University of Maryland, n.d.), only a few departments were represented as fellows in the GWC. Knowing how to read the work of graduate students in various fields was integral to our work in the GWC. While our training stressed WID approaches and mainstream writing center techniques (e.g., nondirective tutoring), my training did not cover linguistic justice.

It was only a few months into working at the GWC that I began to realize the issues of anti-Black linguistic racism that Black graduate student writers were facing. Outside of the fields of sociolinguistics, rhetoric and composition, writing studies, and literacy, Black language is hardly ever acknowledged as an official language (McMurtry, 2021). At the time I was working at GWC, only two other fellows were knowledgeable about linguistic racism and violence, but that was because it was a part of their research.

When a member of my university’s Black Graduate Student Union posted a message on GroupMe saying, “Hey y’all! I have a question for those who are working on thesis and dissertations and what not. How have y’all, if you have, handled not explaining Black vernacular? I was trying to explain to my academic advisor that certain phrases are for the girls that get it, get it,” I knew I needed to respond.

I replied: “I’ve told my advisors that it’s a language with its own linguistic/cultural rules/patterns and that I’m making an intentional rhetorical choice with my audience when I use it for my audience, and because of that, I don’t need to provide context. Also maybe citing scholars writing about Black language to support my rationale.”

“That’s such a great idea to add a citation cause they love those lol thank you!” the graduate student replied.

This moment was just one where I felt the urge to affirm other Black graduate student writers’ languages and literacies. Many of the clients that I assisted told me that they had never visited a writing center before, and the ones that had were taught techniques to exchange their Black language for WME in their academic writing. I was fortunate to be in a graduate program—Language, Writing, and Rhetoric—that not only supported the research of Black language and the cultural politics associated with it, but also affirmed my decision to write in Black language. I knew other Black graduate students would not receive the same kind of support and affirmation as I did because they were coming from programs that had not invested time in Black language scholarship. Additionally, many graduate student clients came to me with their drafts and their margins were full of faculty/advisor comments telling them they needed “serious help with grammar.” I found this process to be similar to the contemporary hush harbors that Carmen Kynard describes in “From Candy Girls to Cyber Sista-Cipher” because this GroupMe was only accessible for Black graduate students and our literacies, hidden in plain sight, where we were discussing and finding ways to resist institutional racism (Kynard, 2010). Similar to how Kynard explains in her article, this GroupMe provided Black graduate students the opportunity to enact Black rhetoric, and regarding these specific messages, it prompted discursive possibilities for responding to anti-Black linguistic racism. This experience is certainly what prompted me to consider including foundational and definitional knowledge about Black language in my posters. It was clear to me that even Black graduate students lacked a rhetorical education of Black language.

Working in the GWC, I recall one international graduate student of color having a paper where a professor wrote something along the lines of: “I have corrected your grammar for the first five pages, but I refuse to correct it for the remainder of the document. Please get assistance with your grammar.” This student wanted to spend our entire time on grammar. While I was able to assist them with their grammar, I framed our consultation around white linguistic hegemony. This student’s first language was not English, and while I don’t know the professor’s race, the attitude from their marginal comments was givin’ white linguistic hegemony. This professor’s dismissive comments about grammar are what inspired me to have a set of demands directed at a specific audience. Furthermore, discursive moments of professors telling students of color—especially Black students—to “fix our grammar” even after the publication of the 2020 CCCC Special Committee’s Demand for Black Linguistic Justice only solidified that teachers outside of language and literacy education were probably unaware of the research dating back decades.

Many of my final consultations before the end of the Spring 2023 semester were with Black women graduate students. One of these graduate students was a Math Education scholar whose research centered on critical race theory (CRT), Black critical theory, and Black girls in STEM. Working with her had been one of the few moments where the consultation truly felt like a kiki cause baby, we was cuttin’ up talking about being Black graduate students in predominantly white academic spaces. Because so much of my literacy education had been English educators teaching me to code-switch, I subconsciously always code-switch in professional settings. For most of my writing center appointments I code-switched. As I currently work through my dissertation though, I’m unlearning the violent literacy education that forced me to write and speak WME in academic settings. With this graduate student, we both not only spoke Black language, but we also spoke about research centering Blackness, race, gender, writing, and education. Because the consultation centered our experiences as Black researchers and educators, it allowed me to actualize the Black dispositions necessary for work in the research and teaching of Black Language (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020). The consultation also allowed me to execute one of the principles of Johnson’s “Critical Race English Education,” specifically addressing “issues of violence, race, whiteness, white supremacy, and anti-black racism within school and out-of-school spaces” (Johnson, 2018). I see the racist feedback she had received on a draft of her work about utilizing CRT and Black critical theory to study Black girls in math as inseparable from anti-Black linguistic racism—that’s the power of white language supremacy, or, assisting “white supremacy by using language to control reality and resources by defining and evaluating people, places, things, reading, writing, rhetoric, pedagogies, and processes in multiple ways that damage our students and our democracy” (“CCCC Statement on White Language Supremacy,” 2021). In other words, they ain’t just wanna restrict how she was writing, they wanted to also restrict what she was writing.

Later that spring semester, I also had the privilege to speak with a Black first-year PhD student in my department about linguistic justice. He was doing a project for a class, and it centered Black language. I was thrilled to recommend Geneva Smitherman’s Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America as a good starting point for researching and writing about the topic. I also made sure to tell him how that book was special to me because it was so affirming of my identity, language, and writing as a Black person. When I told him this, it made me think back to an episode I had recorded on my Black queer podcast, called Black Brew, specifically about the politics of Black language (Green & Love, 2021). This podcast episode, I would argue, is just another medium—public scholarship and Black queer community literacies—in addition to my #BlackLanguageMatters posters that enacts linguistic justice. Again, it’s very clear based on my experiences with other Black graduate students that the nuances of working as a Black queer graduate writing center professional wanting to enact linguistic justice always entail some form of community-engaged literacy work.

Community-Oriented Action for Graduate Writers of Color

One year into this position at the graduate school writing center led me to want to do more work on enacting linguistic justice; thus, I decided to create and place artwork in community spaces where people were writing, tutoring, or doing some form of literacy work. I worked on this poster project independently of my writing center duties, and since most of the work for this poster project occurred during the summer, it was also unpaid work. I used my personal funds to print the posters at an office supply retail store. Approval was not needed to hang my posters in public spaces like bulletin boards, but for office spaces I received approval. While later the posters would become a part of a collaborative process during training, most of the initial work (i.e., conceptualizing the project, designing and printing the posters, and distributing to public spaces) was done independently of my writing center position and was truly a demonstration of how Black queer writing center practitioners commit to linguistic justice work in our communities.

To emulate the community language and literacies of Black Lives Matter protests, signs, and t-shirts (Richardson & Ragland, 2018), this artwork would be a poster defining Black language and linguistic justice and would also include demands and affirmations from Black people. I started by conceptualizing what information I would want to include on the poster. I knew there would be terminology and definitional work that I would need to include on the poster because not everyone looking at it—despite being a writer or assessing someone else’s writing—would know about the scholarship behind Black language and linguistic justice. I decided that I would define three major terms: Black language, anti-Black linguistic racism, and linguistic justice. Just like the Black graduate student that I assisted in that GroupMe, I was certain there were many more graduate students who were unfamiliar with the scholarly validation and amplification of Black language.

I also knew that I would want the poster to have a list of demands and affirmations, with the demands targeting individuals who encourage Black writers to code-switch. Harkening back to that graduate student of color whose professor told them “to seek assistance with their grammar” and that Black woman graduate student who studied CRT and math, I saw the opportunity to extend the concept of code-switching in academic writing. As I argued earlier, the power of white language supremacy is its racist insistence on restricting both how and what people of color are saying. Code-switching is traditionally defined as people of color being taught, requested, or forced to communicate in two different ways: one for the hood and one for the school (Young, 2007). We shouldn’t see code-switching as just the respectability politics of reserving Black language for the fam and not the workplace. In fact, we should extend our conceptualization of code-switching to also the reservation of certain topics (e.g., critical race theory, Black History, intersectionality, racial justice, abolition, etc.) as a way to achieve upward mobility and survival in white academia. This practice, just like the traditional definition of code-switching, requires us folks of color to separate our authentic identities for white people’s comfort and convenience.

As illustrated in Figure 1, I focused on teachers, tutors, and editors. These demands mirror the same demands in the CCCC Position Statement on Black Linguistic Justice (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020). While the demands were targeted at individuals who were using approaches and strategies to stifle Black language, the affirmations were targeted at Black writers. I wanted to address the arguments that I heard about Black language before I developed a Black Linguistic Consciousness: “It’s not a real language; it’s grammatically incorrect English; code-switching is the best option.” The quote “Code-switching will not save Black people,” actually inspired the first major quote in the poster. The CCCC Committee on Black Linguistic Justice explains that many of the pedagogical approaches that writing and literacy teachers have encouraged to their Black students have been code-switching. They note that this is not a celebration of Blackness or our language, but instead is actually a form of anti-Black linguistic racism. They argue that code-switching is racist because it centers whiteness and WME (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020). Encouraging code-switching also continues the myth that learning, speaking, and writing in WME, or other literacies and languages grounded in whiteness, will allow the most social mobility, success, and opportunity (Gee, 2012; Prendergast, 2003; Richardson, 2002; Stuckey, 1990; Wible, 2013; Young, 2007). The first quote in Figure 1, “Telling children that White Mainstream English is needed for survival can no longer be the answer, especially as we are witnessing Black people being mishandled, discriminated against, and murdered while using White Mainstream English, and in some cases, before they even open their mouths” (Baker-Bell, 2020) connects the language and literacy pedagogy to the Black community politics happening outside of the classroom. Specifically, Baker-Bell mentions George Floyd who, before he was murdered, used what many would call Standard American English (SAE). Floyd, begging in SAE/WME, “I can’t breathe,” was still murdered. His murder prompted a series of #BlackLivesMatter uprisings; thus, many Black language scholars noted that the anti-Black violence happening outside the classroom could not be separated from the anti-Black violence happening in the classroom (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020; Baker-Bell, 2020).

For these reasons, I decided to title my poster “#BlackLanguageMatters (#BLM).” At the very bottom of Figure 1 is a QR code. Originally, I had intended to include a list of Black language scholars for people to research if they wanted to know more information, but because of design choices, I was unable to include that list. Instead, I decided to leave a link to the Black Language Syllabus, a resource created by April Baker-Bell and Carmen Kynard to celebrate Black language and promote linguistic justice. I believe providing the QR code to a more extensive digital resource would be more beneficial for early learners of linguistic justice than a list of scholars to research themselves. Additionally, this resource was curated for people wanting to re-educate themselves about Black language and to discover the connection between our language and Black liberation (Baker-Bell & Kynard, 2020).

Figure 1

#BlackLanguageMatters Poster

![Figure 1. Flyer with light brown background and black text over white boxes. The flyer reads: "#BlackLanguageMatters. “Telling children that White Mainstream English is needed for survival can no longer be the answer, especially as we are witnessing Black people being mishandled, discriminated against, and murdered while using White Mainstream English, and in some cases, before they even open their mouths” —April Baker-Bell. Black language: “A style of speaking English words with Black Flava—with Africanized semantic, grammatical, pronunciation, and rhetorical patterns. It comes out of the spirit of U.S. slave descendants” —Geneva Smitherman. Anti-Black Linguistic Racism: “the linguistic violence, persecution, dehumanization, and marginalization that Black Language speakers endure when using their language in schools and in everyday life” —April Baker-Bell. Linguistic Justice: “an antiracist approach to language and literacy education [that dismantles] Anti-Black Linguistic Racism and white linguistic hegemony and supremacy in classrooms and in the world” —April Baker-Bell. Teachers: Stop teaching Black students to code-switch. Tutors: Stop advising Black tutees to code-switch. Editors: Stop forcing Black writers to code-switch. Black language isn’t inferior. Black language is beautiful. Black language isn’t grammatically incorrect. Black language has a grammatical system. White Mainstream English will not save Black people. Black language matters. Your Black language matters."](http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Figure-1.jpg)

After printing the posters, I decided to make a list of locations where I would hang the posters. I decided the first place I would hang the poster would be my graduate student instructor (GSI) office, as seen in Figure 2. This hallway is full of GSI offices and people pass by my office door often, so I knew this location would be where a lot of traffic occurred. Additionally, by placing the poster in the hallway where offices are, students who would be attending office hours would also see the poster. I placed it on my door because I wanted my students—or any English department member—to know my stance on Black language and linguistic justice.

Figure 2

#BLM Poster on my GSI Office Door

The second place I decided to hang my poster was with an English department office that has been invaluable for my community-engaged research: The Center for Literary and Comparative Studies (CLCS). Figure 3 shows one of my posters along with a series of other posters. I also chose CLCS because of its two-year Antiracism initiative that centers on research, teaching, public engagement, communities, and collaboration. CLCS is also integral in supporting graduate students, early and mid-career scholars, and scholars of color. CLCS’s antiracist mission and community-engaged projects make it a hub for the intended audience of my poster: teachers, tutors, and Black writers.

Figure 3

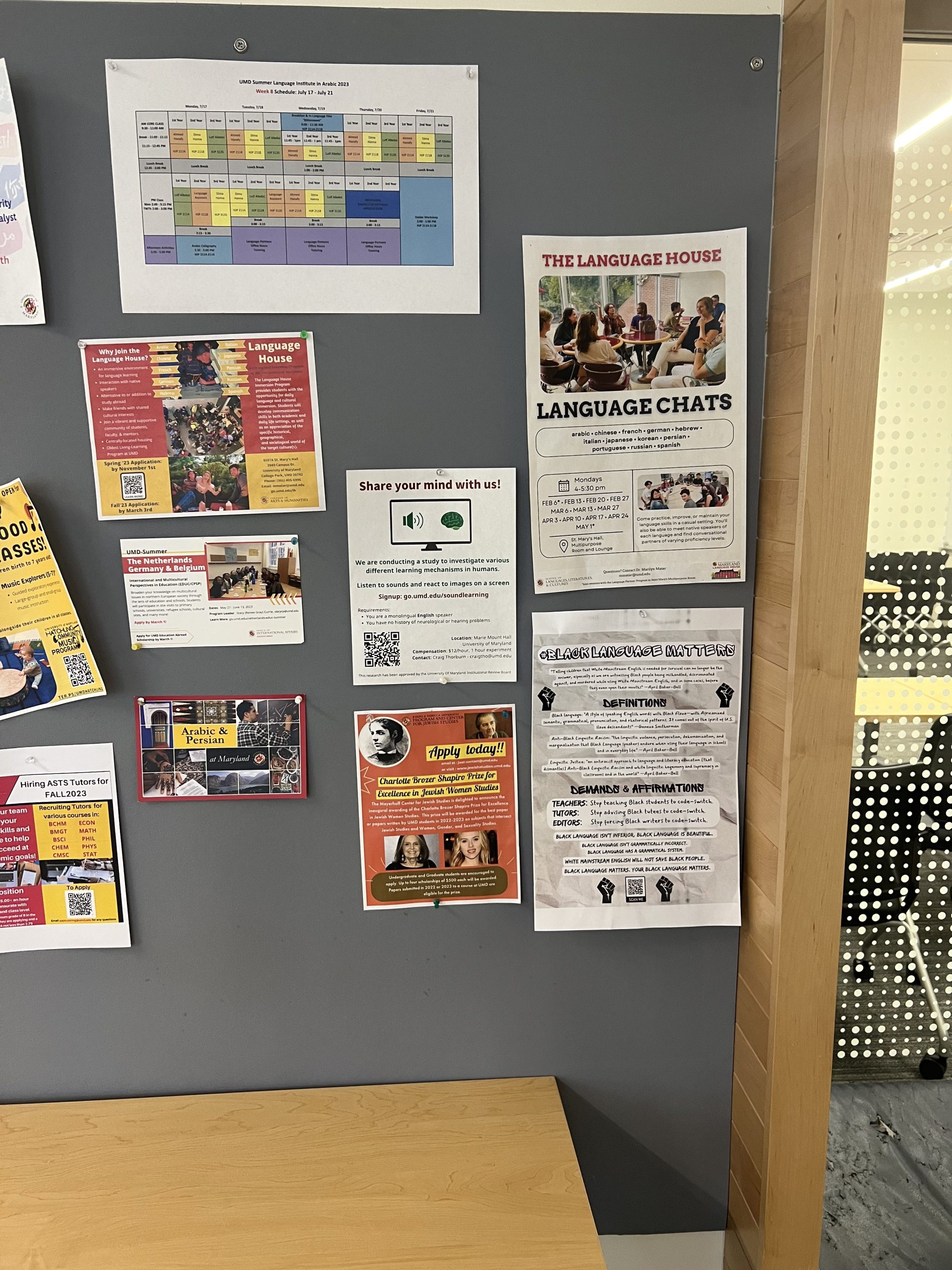

#BLM Poster in CLCS Window

Graduate students are in a unique position as we can both endure linguistic racism from our professors and advisors and perpetuate linguistic racism onto our students. Figure 4 shows my poster hanging in my department’s graduate student lounge. I chose this location because many first-year PhD students and master’s students use this space as a writing space. The lounge is also a space for graduate students to prepare their lunches and sometimes just socialize. In the lounge, there is a bulletin board where other graduate students have hung posters and flyers that might appeal to graduate students. This location might have been the least effective place to hang the #BLM poster simply because the bulletin board has a lot of flyers attached to it and no one has maintained the board. Because I hung the poster in this lounge, I can reach the many graduate students who use the room as a writing space and for some, a space to lesson plan for their first-year writing courses.

Figure 4

#BLM Poster in the Graduate Student Lounge

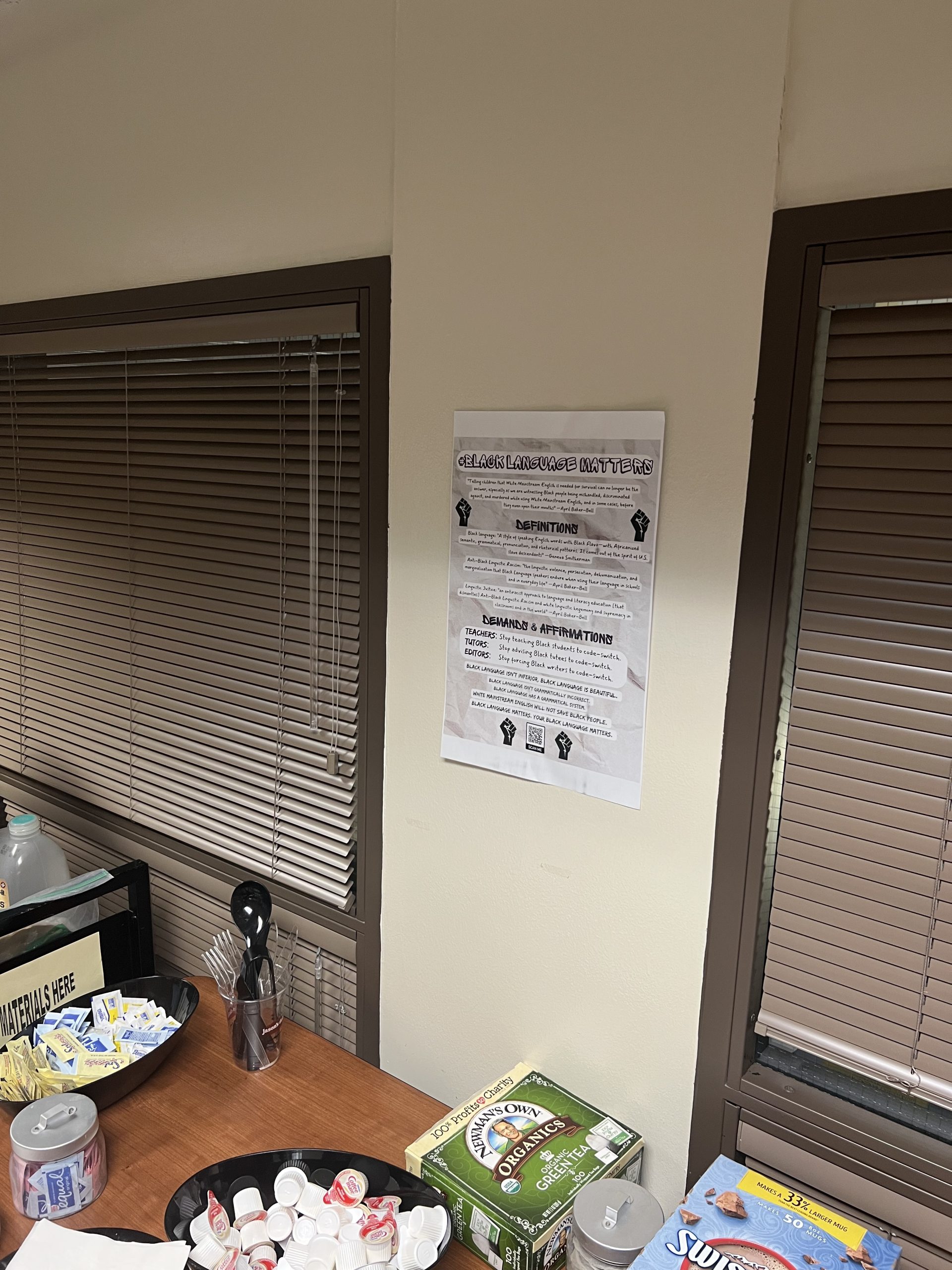

I currently serve in an assistant director role of our FYW program, which has, for the last few years, been working on professional development that centers curricular and instructional approaches toward linguistic justice. In terms of writing center professionals’ allies and community members who can help us enact linguistic justice, my university’s FYW program, in addition to CLCS, is one of them. Figure 5 shows the #BLM poster hung in one of the offices of our first-year writing (FYW) program. I strategically placed the poster in the office where the graduate writing program administrators work. Our graduate writing program administrators have a bifurcated role where we can enact linguistic justice programmatically—when we train new graduate instructors—and instructionally—when we teach our own courses. FYW programs and writing centers work hand in hand with one another, and as someone working in both an FYW admin role and a writing center professional role, I thought placing this poster in the program’s office would help bridge two places that often don’t connect: first-year writing and the graduate school writing center. In order for linguistic justice to touch all writers, it must extend across all academic levels from early childhood education to composition courses to dissertations.

Figure 5

#BLM Poster in FYW Office

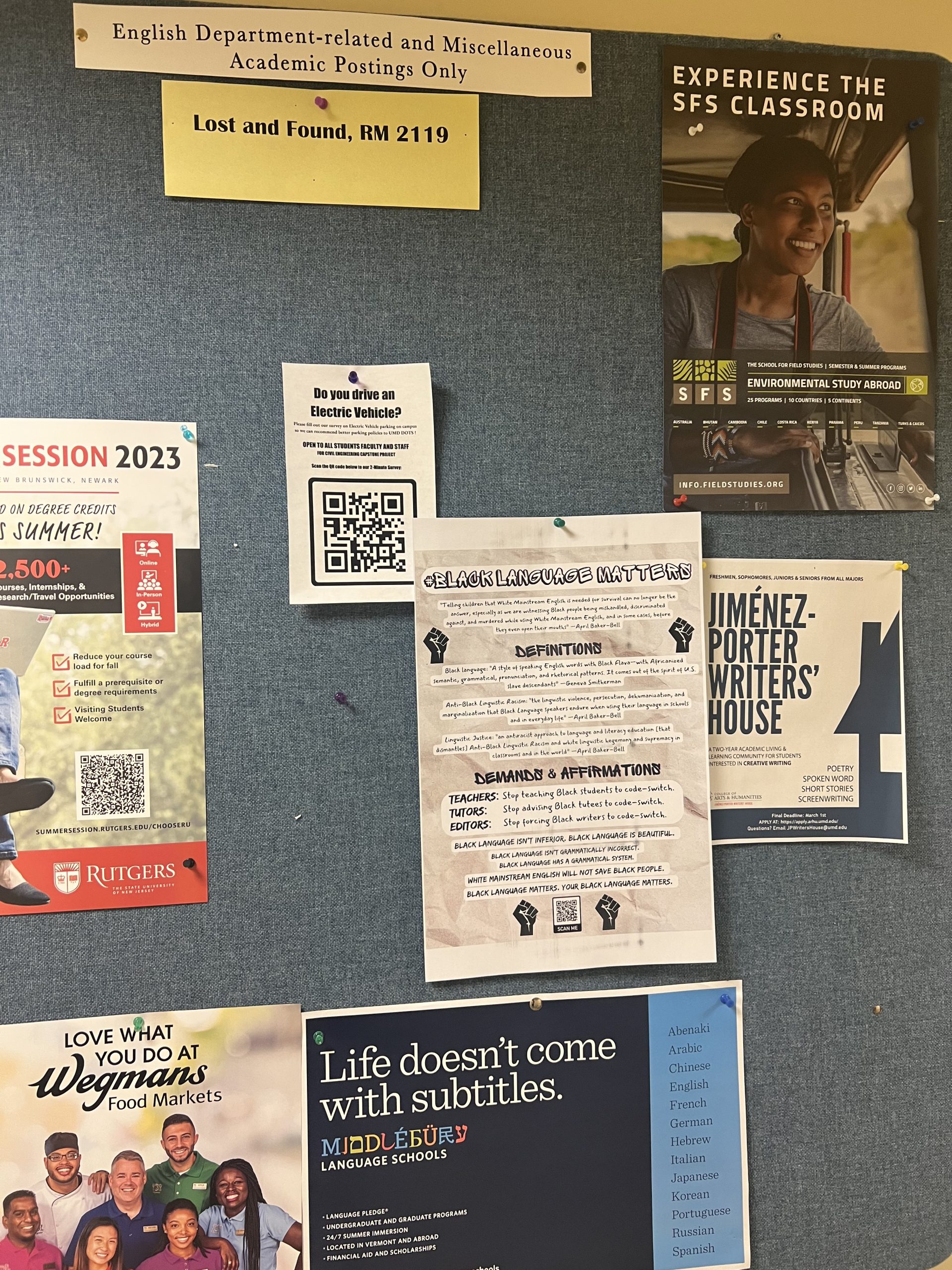

The last place in my department’s building, as shown in Figure 6, where I hung a poster is in high-traffic areas that had bulletin boards. Many of these bulletin boards were located near elevators.

Figure 6

#BLM Poster on Bulletin Board

Our GWC requests fellows to create a “writing-in-the-disciplines” project, and ultimately this is how I conceptualized this community-oriented art project. While this project is oriented in the field of rhetoric and composition, I also see writing center studies as a discipline; therefore, the next place to hang my posters was in the GWC, as shown in Figure 7. I emailed our GWC director to ask if I could hang the poster in the office, and she said yes. She also asked for a copy of this journal article to include training material around linguistic justice. I’m hoping this poster can prompt more conversations between fellows in our GWC as many of our clients are international students and students of color who are being told by advisors, professors, and journal editors to conform to WME. While the decision to code-switch, or conform to WME, is ultimately up to the writer, I’m hoping that my #BLM poster can be generative for GWC tutoring approaches as we expand our consultations to include conversations about white linguistic hegemony and white language supremacy. After distributing this poster in the GWC, our director invited me during the subsequent training to discuss the poster I had designed and how we could enact linguistic justice in our center. At this training, I was able to speak with a range of graduate students from different disciplines and backgrounds.

Figure 7

#BLM Poster in GWC

My university’s Language Science Center (LSC), as shown in Figure 8 was the final place where I hung my #BLM poster. The LSC is dedicated to research around psycholinguistics, second language acquisition, natural language processing, and more. I found this place to be a particularly interesting place to add to my list because, like many language and literacy scholars/educators, they too are conducting research around linguistics. Part of their mission statement is to “Improve awareness and public understanding of language issues.” The LSC is an interdisciplinary center with program members from English, Computer Science, Psychology, Education, Engineering, Neuroscience, Communication, and more. After hanging this poster in the LSC, I decided to apply to join as a member. Joining would allow me more opportunities to interact with other graduate students and professors and do more of the Black queer writing center community work that I’m doing now. I’m expecting to attend LSC events and speak with other academics who are doing work in linguistics and to ask them about their pedagogical approaches when it comes to linguistic diversity and to help promote the scholarship and activism of Black linguistic justice. I’m hoping that the interaction that I had with the Black graduate student in the GroupMe isn’t the last one and that I can meet more Black graduate students interested in this work. Additionally, by engaging with the LSC, I have the possibility to establish more campus allies who want to enact linguistic justice around campus. Since joining the LSC, I have attended one research talk by Black literacy and language scholar Dr. Shenika Hankerson.

Figure 8

#BLM Poster on Bulletin Board in LSC

Conclusion

I had a lot of reflection after hanging my posters and writing this article. Most of the reflection was frustration with me wanting to do more. In my mind, I kept telling myself: “all you did was hang some damn posters.” While I was not financially compensated for this work, my hope is for it to reach Black writers and for them to feel affirmed. Since hanging these posters in writing spaces, I have had numerous graduate students ask me if I hung the posters or tell me that they really liked the posters and were glad that someone had hung them. This feeling of me wanting to do more came from the fact that a lot of academic research, even in the humanities, doesn’t see lived experiences as rigorous research, despite CCCC saying otherwise (2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice, 2020). Devaluing the lived experiences of Black people as research underscores my argument for why our field in rhetoric, composition, and writing centers is especially qualified to respond to these current political moments seeking to assert a white supremacist agenda in education. Right-wing policymakers and racist educators aren’t just restricting how Black folks are writing but are also restricting what we’re writing. Working with the Black graduate student whose work centers on CRT and Black girls in math exemplifies this conundrum. What good is writing in Black language if we can’t even write about our lives, cultural experiences, politics, social movements, and more?

Thinking back to my undergraduate scholarship essay on “outstanding achievement” as an English major, I wonder if this poster project would have been considered outstanding achievement in English studies—or more importantly, would I have considered this work outstanding achievement in English studies? Even after gaining a Black Linguistic Consciousness and understanding that my Black language matters, I still must navigate a profession that still sees my research-affirmed language as “not scholarly.” Additionally, the content of my Black language, such as my research on critical race theory, prison abolition, Black queer activism, and storytelling, is also criticized and deemed unscholarly. Even now as a doctoral candidate applying for summer funding to external sources outside of my department or field of rhetoric and writing studies, I sometimes reflect on how I write and what I write as a Black queer person will impact the material conditions of my life. This concern is evidenced by the graduate writers I meet during my appointments in fields that don’t recognize Black language as a legitimate language or by graduate students who must endure anti-Black linguistic racism from their advisors. Moreover, with the continued rise of Black women professors and CRT scholars losing their jobs, Black folk’s writing needs defending now more than ever. This poster project and article attempts to do just that by affirming Black language and amplifying linguistic justice in community spaces outside of rhetoric and composition.

Sure, I sprinkled some AAVE up in this paper, but being “allowed” to write in my tongue should not be, and is not, the extent of Black linguistic justice. The function of white language supremacy is for us to see and write about the world through a colorblind and apolitical lens. Writing about anti-Black linguistic racism and Black language is just one example of how linguistic justice is enacted to combat white language supremacy. Restricting Black folks from writing about our own experiences, from learning accurate Black history, and from studying Black feminism is just as racist as restricting Black folks from using Black language in our writing. And when politicians craft arguments against race-conscious admissions and student debt relief, they are simply reifying a racial capitalist system that denies Black people equal access and opportunity to education and a fulfilling life. Their rhetoric, grounded in white language supremacy, influences the material conditions of Black people just like the work we do in writing centers. Our work as writing center practitioners should not stop at tutoring and we shouldn’t confine ourselves to the walls of our center or academia. The work we do actually affects people’s livelihoods—no cap. So, in an era where white supremacy’s presence seems unceasing, we in rhetoric, writing, literacy, and writing centers must commit to enacting linguistic justice so that we can stop the systemic restraints on how Black people are writing and what Black people are writing.

References

2020 CCCC Special Committee on Composing a CCCC Statement on Anti-Black Racism and Black Linguistic Justice. (2020). This ain’t another statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice! Conference on College Composition and Communication. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/demand-for-black-linguistic-justice

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic Justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Baker-Bell, A., & Kynard, C. (2020). #BlackLanguageSyllabus. Black linguistic justice. http://www.blacklanguagesyllabus.com/

Blau, S., Hall, J., & Sparks, S. (2002). Guilt-free tutoring: Rethinking how we tutor non-native-English-speaking students. The Writing Center Journal, 23(1), 23–44.

CCCC Statement on White Language Supremacy. (2021, July 7). Conference on College Composition and Communication. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/white-language-supremacy/

Committee on CCCC Language Statement. (1974). Students’ right to their own language. College Composition and Communication, 25(3), 1–32.

Faison, W. (2018). Black bodies, Black language: Exploring the use of Black language as a tool of survival in the writing center. The Peer Review, 2(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/relationality-si/black-bodies-black-language-exploring-the-use-of-black-language-as-a-tool-of-survival-in-the-writing-center/

Faison, W., & Treviño, A. (2017). Race, retention, language, and literacy: The hidden curriculum of the writing center. The Peer Review, 1(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/race-retention-language-and -literacy-the-hidden-curriculum-of-the-writing-center/

Fisher, M. (2009). Black literate lives: Historical and contemporary perspectives. Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2012). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. Routledge.

Gilyard, K. (1996). Language and politics. In Let’s flip the script: An African American discourse on language, literature, and learning. Wayne State University Press.

Green, E., & Love, J. (2021). The politics of AAVE. Retrieved July 10, 2023, from https://open.spotify.com/episode/2JqFXAlS2UIp88XlneOoWX?si=5468ffcaaa744d48

Greenfield, L. (2019). Radical writing center praxis: A paradigm for ethical political engagement. Utah State University Press.

Hyland, K. (2008). Genre and academic writing in the disciplines. Language Teaching, 41(4), 542–562.

Johnson, L. L. (2018). Where do we go from here? Toward a critical race English education. Research in the Teaching of English, 53(2), 102–124.

Kynard, C. (2010). From candy girls to cyber sista-cipher: Narrating Black females’ color-consciousness and counterstories in “and” out “of School.” Harvard Educational Review, 80(1), 30–52.

Kynard, C. (2013). Vernacular insurrections: Race, Black protest, and the new century in composition-literacies studies. State University of New York Press.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: A critical examination of race, place, and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2). http://www.praxisuwc.com/162-lockett

Logan, S. W. (2008). Liberating language: Sites of rhetorical education in nineteenth-century Black America. Southern Illinois University Press.

Luna, I. (2023, July 27). New slavery curriculum in Florida is latest in century of “undermining history.” USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/07/27/historian-warns-against-floridas-slavery-curriculum/70463676007/

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2014). Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies, 42(1), 54–78.

McMurtry, T. (2021). With liberty and Black linguistic justice for all: Pledging allegiance to anti-racist language pedagogy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 65(2), 175–178.

Prendergast, C. (2003). Literacy and racial justice: The politics of learning after Brown v. Board of Education. Southern Illinois University Press.

Richardson, E. (2002). African American literacies. Routledge.

Richardson, E., & Ragland, A. (2018). #StayWoke: The language and literacies of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Community Literacy Journal, 12(2), 27–56.

Royster, J. J. (2000). Traces of a stream: Literacy and social change among African American women. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Smitherman, G. (1977). Talkin and testifyin: The language of Black America. Wayne State University Press.

Stuckey, J. E. (1990). The violence of literacy. Heinemann.

The University of Maryland. (n.d.). Graduate programs. The Graduate School. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://gradschool.umd.edu/graduate-programs, https://gradschool.umd.edu/

Totenberg, N. (2023, June 29). Supreme Court guts affirmative action, effectively ending race-conscious admissions. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/29/1181138066/affirmative-action-supreme-court-decision

Turner, C. (2023, June 30). What the supreme court’s rejection of student loan relief means for borrowers. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2023/06/30/1176839127/supreme-court-student-loan-forgiveness-decision

Wible, S. (2013). Shaping language policy in the U.S.: The role of composition studies. Southern Illinois University Press.

Young, V. A. (2007). Your average nigga: Performing race, literacy and masculinity. Wayne State University Press.