Reviewed by Mary Helen Truglia

Indiana University, Bloomington

Melzer, D. (2023). Reconstructing Response to Student Writing: A National Study from Across the Curriculum. Utah State University Press.

Dan Melzer’s Reconstructing Response to Student Writing is a significant and positive addition to the realm of writing feedback and student writer perceptions. In this text, Melzer provides clearly explained data from a nationwide study to support pedagogical practices both for instructors and others who interact with student writing, including writing center administrators and tutors. While the primary audiences for this text may be writing program administrators, particularly those working in first-year writing or Writing Across the Curriculum, and teachers themselves, I would argue that this text is also useful to anyone involved in college level writing, and especially folks who work in and with writing courses via the writing center and within a campus teaching and learning center or pedagogy workshop. The first and final chapters provide well-constructed overviews of the central study of student writing and responses, while the middle chapters use Melzer’s constructivist heuristic chart to delineate trends, patterns, challenges, and possible future-oriented changes based upon the data of the study. Tutors may better appreciate certain excerpts from the text, but I found the full book to be of value to writing center administrators and instructors who are connected to the writing center, and thus I would primarily recommend it for those key audiences.

The opening of Chapter 1 is framed by Melzer’s own history of experiencing a lack of student engagement with his feedback on their writing assignments. Following upon that history, he wanted to create a study to begin to answer the following inquiries:

What did teachers across disciplines focus on when they responded, and what were students’ perspectives on the feedback they received from their college teachers? When students engaged in peer response or self-assessment, how did their feedback and self-reflections differ from teacher feedback? Were there national trends in the ways teachers across disciplines respond that could help inform my teaching and the advice I gave to teachers in writing across the curriculum (WAC) faculty development workshops? (p.4)

Melzer notes that this text is the second part of an ongoing study (continuing from his 2014 work Assignments Across the Curriculum) to investigate trends in writing at the university level across institutions in the United States. This current section of the study, he explains, aims to give a more “panoramic view” of various forms of response to college writing and provide more context by considering the “multiple factors and actors” that constitute responses (p.6). He is working with a significant body of data, over one thousand rough and final drafts of student writing as well as self-reflective analysis of the same, and coding analyses of tens of thousands of instructor and peer comments. One aspect that sets this study apart is his consideration of the impact and results of these comments, not only the original comments themselves. I see this echoed in experiences such as student writers bringing in their instructor’s comments to a writing tutoring session and asking the tutor to help them parse what the responses from the instructor are, and how to respond to those.

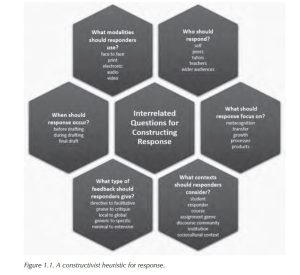

Using constructivist response research as a guiding model, Melzer creates a heuristic chart (pleasantly hexagonal) to visualize the set of practices and contexts that writing instructors and students should consider in providing and working with responses. Constructivist response research prioritizes the socio-cultural contexts of the learning process and the learner’s own uniquely singular role in the creation and recollection of knowledge as well as aiming to facilitate interactive dialogue among and between instructors and students.

Figure 1. Figure showing a chart from Melzer’s book that visualizes the set of practices and contexts that writing instructors and students should consider in providing and working with responses from the author’s book [Reproduced with permission].

None of the individual components are new or struck me as groundbreaking, and yet it was so helpful to see them synthesized and arranged in this visual way through the hexagonal chart because it provides a guide for the multifaceted perspectives and contexts that writer, fellow students, instructor, and at times tutor, should keep in mind as they formulate ways to provide feedback and reflection. Although the chart is by no means all-encompassing, it nevertheless provides an easily consumable synopsis of the exigencies, actants, and actions within the writing and feedback processes. I can imagine this model being particularly useful for early-career instructors as well as departments and interdisciplinary faculty groups looking to reconsider their response patterns and practices, as it could open discussions to align and strengthen practices across a department or multi-section course, pointing to current strengths and gaps. Students too would benefit from seeing and/or using this heuristic as a way of showing transparency about the goals of the writing and response practices they are being asked to do in a given course. Melzer notes this as well, stating that the tool “emphasizes the student: student self-assessment, students’ literacy histories, and students’ ability to transfer knowledge to future writing contexts” (p.9).

Melzer notes that this heuristic draws upon not only his own national study but a wide-ranging literature review encompassing key aspects from Writing Studies, English as a Second/Foreign Language, Writing Across the Curriculum, and even international scholarship (published in English). For his study begun in 2018, he focused on digital student portfolios. He acknowledges that there is a significant skew towards first-year writing courses (70% of the data corpus), but this “reflects the greater availability of ePortfolios from [FYW] and not any intent on [his] part to have a larger representation from first-year writing courses” (p.11). The other 30% of data points range from across disciplines and go beyond students in their first year. He does a thorough and thoughtful job explaining his process for data analysis, which first required a review of literature on not just teacher and peer response to college writing but also university-level student self-assessment of their writing. This review, in addition to providing background sources and methods for data analysis, also filled a gap Melzer identifies to synthesize teacher, peer, and student response as well as theories from Writing Studies, WAC, and ESL/EFL and domestic and international publications on response. He has chosen these all with a focus on undergraduate level college writing (to somewhat limit the scope). I also appreciated that he takes time to not only thank but also explain the level of assistance provided by Lombardi and Quinn, PhD students at UC Davis, who contributed to the project via the portfolio “sense-checking” (Creswell 2009). This explicit note to include and respect the amount of graduate-level research assistance emphasizes Melzer’s focus on students’ value and their importance in the writing and feedback process, at all ranks. This research by the team builds upon a relatively limited body of studies on response by students upon teacher and peer feedback. In a brief limitations section, Melzer reiterates that his goal with this text, and with the study, is to look with a wider panoramic lens to see patterns in writing and responding at institutions across the United States.

Chapter 2 delves further into how Melzer decided upon the questions included in the central constructivist heuristic for response (see page 8 of the text) and uses the six questions and their subcategories as a way to organize his literature synthesis. The chapter opens with further details on how Melzer conducted the literature review using a snowballing technique (reading all relevant sources cited in the bibliographies of books and journal articles found via library database searches). He begins with well-known research from Nancy Sommers, Lil Brannon, and C.H. Knoblauch from the 1980s, which focused on teacher commenting and looks at the patterns and gaps moving forward to a very recent addition, Stephanie Crook’s 2022 article “A Social-Constructionist Review of Feedback and Revision Research” in College Composition and Communication, which was coming out as he was making final edits to this text. This capacious and historical range enhanced my view of Melzer’s argument, as it showed an attentiveness to relevant and related sources from the past five decades, and as a bonus, provides a list of sources for the reader in the bibliography without the need for them to perform their own “snowballing” on this specific topic. This chapter presents the findings of that research and the ways in which they influenced the study Melzer conducts. I do not have space here to enumerate the many useful examples he raises but would encourage researchers interested in this aspect of writing practices to of course consider reading this full book, but particularly this chapter as they begin their own reviews. One evidential aspect that stood out to me was that in ESL/EFL courses, the traditional way of thinking has assumed an expectation that “teacher response would lead to more significant revisions than response from peers who are language learners [but] researchers have found that, with the exception of courses made up of beginning English language learners, peer response is nearly equivalent to and sometimes even more helpful than teacher response” (p.25). This is mitigated by studies that do support that English language learners “may be skeptical of the value of peer feedback and may value teacher feedback far more” (p.26). For both English language learning students and native speakers, the research shows that students need training, scaffolding, and even explicit scripts to give one another useful and actionable feedback. Melzer is careful to note that this positive use of peer response does not mean that instructors should replace teacher responses with peer feedback.

There is a too brief section on writing tutors and their place in this response network on pages 28-29. I appreciate the inclusion of these other agents but wish this section had been expanded, especially since the literature review of writing center tutors’ impact cited here was consistently positive, and the most recent study cited was 2018 (pre-pandemic). Granted, this interaction does not as broadly affect large swaths of the student populations being reviewed, since it of course is contingent upon students who both went to the writing center and then did something with the responses that they received during tutorials. This non-classmate-but-still-peer and non-teacher response is, in my opinion, a valuable place for further research. Later in the chapter, when focusing on Transfer and Metacognition, Melzer describes transfer as a “neglected subject in US research on response, with the exception of a recent increased interest in transfer and writing center tutoring, including a [2020] transfer-themed issue of The Writing Lab Newsletter” (p.34).

For writing center folks, I would argue, transfer and ‘feedforward’ are almost always a part of a tutor-student interaction because tutors themselves may never see this same student or same assignment moving forward. As writing centers/tutor impacts were one small part of this literature review and not really a part of this study, I cannot entirely fault Melzer for not dedicating much further space to investigating them (tutors are mentioned briefly across the other chapters), but I would strongly encourage TPR readers to use this book as a source for their own research into writing center practices and effectiveness, and/or as a starting point for proposing a parallel study to Melzer’s that focuses on these same concerns within writing center practice. I also wanted to point to an important section from pages 37-42 that considers the identities and contexts (including but not limited to race, gender, goals, previous writing literacy experiences, and many more) of the student writer and the responder, and how those will influence their response, as well as how students might receive and interact with those responses. Writing center administrators and teachers of tutor training courses (who often are one and the same) could easily excerpt this section for use as a training text in concert with scholarship on these categories by writing studies scholars.

Chapter 3 shifts to focus on teacher response, using the 600+ teacher responses from Melzer’s study. Due to the nature of the dataset (available student ePortfolios), the study “only [has] the teacher comments that students chose to include [… and does not include] evidence from classroom observations or interviews with the teachers” (p.53). While this does limit what can be drawn from the study, I believe that it also usefully pushes to the forefront the nature of the responses themselves. There are several fascinating connections between the teacher response and the student reflections upon those, one notable aspect being the propensity for teachers to connect their responses to the genre within the course, to focus on correctness, and to praise strong aspects of student writing, but rarely to comment explicitly on how aspects of the current assignment or task could be applied to students’ future writing contexts. I was also unsurprised, based on my own teaching experience with undergraduate students, to see that the perception of “teacher as evaluator/judge” rather than “teacher as guide/mentor” is pervasive across the majority of students, and there were a limited number of teachers in the study, who explicitly gave the students a recognizable audience beyond themselves. I look forward to further research on ways that instructors can help to shift that towards a growth and learning mindset, both from the instructor and student perspectives. In another short but useful section on the intermediary audience of the writing center tutor, several students in the study described that “tutor response helped them rethink their focus and organization and improve their writing,” followed by some excerpts from student reflections on working with a tutor (p.57). This section reiterates what writing center folks are already deeply aware of, however it could serve as an excellent piece of evidence for upper administration or other stakeholders looking for external research to support the value and return on investment of a writing center/tutoring program. This section also references the pervasive myth that teachers unfortunately sometimes perpetuate: the writing center is a place where students can go to fix up their papers or have them fixed, especially with lower-order sentence level issues. Although too brief, the subsequent section on friends and family serving in the respondent role as quasi-teachers or additional teachers, “hoping for an extra layer of feedback on organization, development, and editing” (p.60) was helpful and interesting. Later in the chapter, data from the study reveals that “teachers rarely make the connection between the work of the class and the work of academic discourse communities” and that they frequently “fail to consider the sociocultural contexts of writing in their response” (p.69, 70); teachers or individuals working with instructors may want to consider sharing this with them/with colleagues to provide evidence-based changes and improvements to their feedback systems and habits.

Chapter 4 is also framed by the constructivist heuristic, but here focuses on peer-to-peer responses to student writing. I wanted to cheer and print posters to share that effective peer feedback is possible, but absolutely needs to be scaffolded and guided throughout the course and for each assignment with instructors. Melzer here argues that, as per the results of this study, well-organized and supported peer feedback is as, if not more, effective than teacher response. The study shows that across 400+ peer responses, “peers focus on global concerns, make specific suggestions, are generous in offering praise, and ask open-ended questions that lead to further content revision”; this is particularly the case when teachers guide peer review and response with “scripts that encourage specific response focused on content” (p.91). The chapter takes time to address two well-anthologized perceptions by some student writers: one, that peer feedback is not useful either because they are being reviewed by someone at the same or a lower writing level than themselves, and two, that even if the response is helpful, it may not fit what the teacher is looking for in the assignment.

Luckily, in their self-reflections, many students will admit that going through the peer review process was a boon to them, even if they were originally skeptical. The section on process memos on pages 95-97 is fascinating and could be shared with any instructor looking to modify their current practice; it offers a model of how to structure a process response for instructors who may not have asked students to perform this reflective writing previously. This could also be used to structure a verbal version of this reflective mental work within a tutorial context. As writing center folks are well aware, sharing one’s writing and giving feedback are both deeply personal and vulnerable processes, but, at times, teachers do not always explicitly acknowledge that same writing context for peer-to-peer response; Melzer finds this context of vulnerability and fear is a vital aspect for teachers to consider in providing response to student writing. At the heart of the chapter is Melzer’s repeated point that through peer response, students learn “the constructivist lesson that writing is a social process, and this caused many of them to change their entire conception of their writing processes” (p.110).

In a meta fashion, Chapter 5 reflects on the study by investigating students’ self-assessment of their own writing. As in Chapter 3, this portion of the study shows that students value not only achieving success on individual assignments, but also clear responses that they can understand how to transfer and apply across other contexts. Again, for those searching for evidence to confirm this, the chapter presents data from the study to show that students have a strong ability to “assess their own writing and meaningfully reflect on their writing habits, processes, and growth” (p.112). This becomes particularly useful when there is space in the course for students to create a dialogue between their self-assessment and response from their teachers. Melzer suggests an “easy to implement tool for self-reflection […], a brief process memo submitted with a draft” but also notes that the study shows very few instructors entering into dialogue with these memos (p.113). The good news in this chapter also includes the fact that within the study, students are more likely to consider transfer, even when not specifically prompted to do so. Another wonderful moment is the excerpt where a student comes to a realization about their writing as a process. There are also less philosophical reflections, including students who view the revision process not as a re-seeing, but a way to achieve a stronger grade. The important takeaway from this chapter reinforces the multiple agents at work in the learning process: student self-reflections should be considered in concert with peer and teacher responses, but shifting the focus from teacher to student response places agency again in the writer’s hands, as all good tutoring sessions aim to do.

Chapter 6 moves to zoom out a bit again to connect the various findings described in earlier chapters, including asking questions about how to implement the broader findings, and offering suggestions for further research in these areas. As I envisioned during the first introduction of the constructivist heuristic, Melzer here suggests that the heuristic is not only for researchers but for instructors across the disciplines. As he notes, this suggested constructivist approach to considering response in all of its forms “encourages us to go well beyond the teacher/student dyad […] and consider a variety of contexts that shape response: the students’ literacy history, the genres we assign and their discourse community contexts, our own preferences and biases as teachers, the modes in which we respond, and the broader institutional and sociocultural contexts that inform the entire response construct” (p.129). One small critique I had here was the emphasis on “faculty” as the primary teacher role, when often, especially at the first-year level, the “faculty member” giving response feedback and creating scaffolding for peer response and facilitating self-reflection is a graduate student instructor, adjunct instructor, or member of the faculty with a high teaching load, who does not have the affordances of time or even syllabus creation autonomy that a faculty member who has the combined privileges of being full-time, perhaps tenured, and with a limited teaching load might. To help with some of that issue, this chapter does offer a few suggestions for deemphasizing grading and grades as a focus for a course. Contract or ‘specs’ grading, where many assignments are completion based and focus more on student process and labor, is one approach. Another would be leading entire courses that are credit/no credit, if your institution offers such an option. This argument also supports the writing center’s position that tutors do not promise to affect grades or to “fix” student work, but instead offer another place for the student writer to get feedback, reflect on their own process, and gain/practice writing techniques that will be part of a repository beyond this one particular assignment or grade.

I fully agree with Melzer’s claim that “in shifting response and assessment away from teachers and toward students, the ultimate goal is to empower students to have the self-efficacy as writers to be able to monitor their own writing processes and learn to better assess their own strengths and challenges as writers” (p.134). As with the conclusion of the previous chapter, Melzer’s study results show clear data points of efficacy for practices that are often already common within the writing center but harder to track because of the nature of tutorials and student reporting of impact. My main issue with the postscript was that it created too many ideas – a good challenge to have! Melzer, learning from his own study, reflects on his two decades of researching college writing and response, and provides a sense of the importance and implications of this study and response to student writing broadly for not only teachers, but writing program administrators and upper-level administrators, who often want to have evidence-based solutions to present to funding boards and so forth. These implications are also significant for writing center tutors, and this was unsurprisingly of particular interest to me, and made me want to conduct a parallel study of student response to tutor feedback. Much of the postscript is comprised of categories of suggestions for places where the findings of this book can be implemented. These range from the assignment level where Melzer suggests that instructors could try a ‘writing to learn’ assignment, like a reading journal, to the curricular and university level, where administrators could design a coordinated vertical sequence of writing and response experiences from the first-year/lower division coursework into writing within the majors. This section culminates with a call for a deeper investment, both intellectually and fiscally, in Writing Across the Curriculum. I deeply hope that readers of this book from those various audiences can utilize the data presented in Melzer’s study and this excellent textual guide to effect change in ways that make sense for their program or institution, and perhaps even more importantly, are useful and agential for student writers.