Sheila Camacho, Middlebury College

Genie N. Giaimo, Hofstra University

Abstract

This study examines the session note taking practices of ~90 undergraduate peer tutors at Middlebury College–an undergraduate small liberal arts college –focusing specifically on reported anti-racism practices in the writing center. In analyzing session notes over six semesters, we observed a noticeable decline in tutor reported engagement with anti-racist themes (broadly conceived to include racial and linguistic justice, as well as emotional labor) from 2021 to 2023. We further found that peer tutors are engaging with academic discussions of race and the emotional elements of racial justice as they arise in tutoring sessions, more often than they are with linguistic justice. In a follow-up training in Fall 2023, we found that tutors report being reluctant to characterize their practices as intentionally anti-racist. From these findings, we believe that anti-racist work is not only cyclical, with some populations of tutors (such as the 2021 cohort, especially BIPOC and queer tutors) taking up the charge of doing this work, but, also that there remains confusion around what can be defined as anti-racist tutoring praxis (despite trainings, onboarding, conversations, and regular nudging). We conclude that anti-racist work, while a vital part of writing center praxis, needs more guidance and clarity around intentional practices as well as broader buy-in from the institution. At a time when DEI and anti-racist work is under threat across higher education, this buy-in might not be forthcoming. To that point, we conclude with a discussion about how institutional values and policies encourage or forestall anti-racist writing work.

Keywords: anti-racism; session notes; writing centers; DEI; assessment.

The Story Behind the Research

For the past five years, Middlebury College has been working towards becoming an anti-racist and more inclusive writing center. Prior to 2019, peer tutors were hired based on an awards system rather than an application system; first year students nominated for a writing prize were given a job as a peer writing tutor in the center. This hiring process overemphasized faculty impressions of student writing “success” (which was often inexorably bound with grades) and reinforced a hierarchy culture wherein the “best” students in the first year writing courses were selected to mentor those who were struggling. Unsurprisingly, this hiring model often meant that white students were hired as peer writing tutors (PWTs), and students of color were identified as those needing writing support. As Grimm (2011) describes, it is not uncommon for writing centers to be staffed by “friendly white people,” which demonstrates how our center is “based on assumptions about language, literacy, and learning that privileged white mainstream students” (p.75). In 2019, members of the writing center, specifically peer tutors, were hungry for change and a new non-tenure track director was hired to implement intentional training courses and establish a new hiring process, which explicitly included recruitment from BIPOC, first-generation, Multilingual, and queer populations. The new process also included a tutor training course and a secondary application hiring stream for students who could not commit to a semester-long class. In its first year, even with the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, which included campus closure from March to September 2020, this new model of recruitment and hiring yielded a far more diverse peer tutor staff (moving from less than 20% BIPOC, to around 40% BIPOC). Along with a shift in tutor staff demographics, new opportunities for leadership, research, and pedagogical training arose, which impacted the retention and thriving of all peer tutors. For example, tutors were mentored in producing research for all-staff training and publications as part of post-college preparation for professional and academic work (see “Statement on Anti-Racist and Social Justice Work in the Middlebury Writing Center” for more detail).

During this time, tutors expressed a desire in anti-racist tutor training as the 2020 summer of protest and activism for Black Lives intensified, once again. Together, tutors and the director of the center crafted a strategic plan to make our writing center not only more diverse and supportive to BIPOC tutors, but, also, to investigate our training practices, our mission, and our ethos. From this work, we made several changes, which included affinity groups and a BIPOC-student specific set of recruitment events. We created a mentorship program. And we developed several in-house training approaches in collaboration with scholars in the field as well as through community-directed and tutor-led research-informed practice. We also held several listening sessions as part of our strategic plan where tutors shared their experiences with race on campus, shared their training on equity and inclusion work, examined models of inclusive and diverse spaces on our college campus, engaged in discussion about current anti-racist praxis in writing centers, and identified pressure points in the work tutors were already doing to support anti-racist work on campus. These meetings were organized and held by the writing center director and head peer tutors during the 2020 – 2021 academic year. Over 95% of the tutors attended these sessions and contributed to our “Statement on Anti-Racist and Social Justice Work in the Middlebury Writing Center” (2020).

Currently, our writing center provides training sessions on anti-racist practices and inclusivity frameworks. Our tutors are taught to actively listen to their peers and engage with their emotions and their thoughts. In training, we highlight signs of whiteness culture, and how it shows up in our work through perfectionism, urgency, defensiveness, and individualism (Camarillo, 2019). Our tutors are also trained to redirect conversations about race and power structures to be more productive and relevant to students’ learning. Our tutors also identify the hidden curriculum of higher education and uplift conversations about power, academic standards, and emphasize the importance of the writing process. They are also trained to engage with the emotional wellbeing of writers alongside community and self-care.

In our center, tutors are both required and trained to complete a session note after each tutorial; while these documents are primarily used for reflective and pedagogical purposes internal to the center, they can also be shared with external parties like professors and writers, upon request. Typically, a tutor will share session notes with students who attend sessions as “proof” for attending the writing center, or course embedded tutors might share their notes with the course instructor. However, this is not standard practice; it is by request of the writer/professor and occurs infrequently (less than 20% of tutorials). Upon reading the session note form–not the tutor responses–a small but vocal set of faculty were angered by the inclusion of questions about anti-racism on our session note form. Though this document has been primarily used internally for tutors to reflect and report on their sessions, a few of these faculty felt like those questions infringed on their academic freedom, and they worried that we were radicalizing the work of the writing center with “Kendi-style” anti-racist materials. Here, the faculty cite the author and public intellectual, Ibram X. Kendi, who has become a shorthand often evoked by the rightwing to signify “anti-racist indoctrination.”

The pushback on anti-racist praxis–even to questions that were used internally for administrative and research purposes–as well as tutors’ reported struggle to talk about race in the writing center during our 2023 listening session led us to wonder how tutors wrote about their anti-racist tutor training and reflected on anti-racism in their session notes; here, we were more interested in tutors’ reported practices as opposed to external perceptions and anxieties about writing center praxis. We ultimately took the external pressure regarding our anti-racist praxis as an opportunity to assess these practices. We conducted a linguistic assessment on session notes created between 2020 and 2023, focusing on notes where tutors intentionally reported engaging in anti-racist training work by clicking “yes” to question 4–Did you engage in anti-racist work (pedagogy, theory, discussion) with the writers in the session? If “Yes” please detail in the comments question, below–in our form. We then sorted notes by thematic references to assignments, student-tutor interactions, and other more descriptive frames (see methods section for more detail). Our analysis found a marked decline in tutor reportage of engaging anti-racist practices from 2021 onward, despite continued discussions and training sessions on both writing session notes and engaging in anti-racist tutoring praxis. To that end, in fall 2023, we held a listening session where we found that peer tutors were uncomfortable with talking about race and identity in tutoring sessions. Several tutors also felt that what they did was not “big enough” to “count” as anti-racist practice.

From the beginning of this work, there were profound conflicts between stakeholders who see the writing center as a site of literacy regulation and those who see the space as one of racial and linguistic liberation. Though we share here some complaints lodged by faculty and upper-administration about the writing center director and their focus on anti-racism, we also see tutor staff turnover and the chilling effects on DEI work around the country as further impacting anti-racist work in our center. Below, we share findings focused on how tutors describe anti-racist praxis in their session notes. While session notes can only capture what tutors choose to share, we believe that they are an ideal document to get a macro-level view of tutor praxis and training uptake in writing centers, especially over time.

Literature Review

Racism in Writing Centers

Writing centers work as a pillar of support for marginalized students on college campuses, bridging academic resources through peer-led conversations. However, the origins of writing centers are rooted in promoting an institutional systemic norm that emphasizes the use of standardized English and grammar (Boquet, 1999). Despite shifting from remedial models and writing drills, writing centers still hold onto the legacies of instruction that come from institutional pressures (Boquet, 1999).

Even now, writing centers are steeped in classed and racialized framings of “good” and “bad” writers and, while we might believe that the past racist framings of writing center work and mission are behind us (Greenfield & Rowan, 2011), as our experiences enacting anti-racist praxis in our writing center demonstrates, they are not. It’s a consequence of being a part of an institution that benefits from power structures and caters to the upper class. As a result, writing centers are also implicated in reproducing and fostering racism; this undergirds Victor Villanueva’s (2006) argument that writing centers have entered a phase of “New Racism” (p. 11). While writing centers might believe that not interacting with race is an act of resistance against the institution, color blindness is a marker of Villanueva’s (2006) “New Racism.” Yet there are often few avenues to have casual conversations about race and its impact on student writing and experiences (Villanueva, 2006). Villanueva recalls an example of a student of color coming into the writing center hoping to engage in a conversation about race and the character development of his book. However, the conversation of race made the tutor uncomfortable so, instead, the tutor redirected the session to surface-level assistance on grammar and essay structure. Consequently, the student left feeling unfulfilled and insecure about the strength of their argument.

Through Villanueva’s example, Moira Ozias and Beth Godbee conclude that writing centers need to take actionable steps towards committing to becoming anti-racist spaces that dismantle institutional neutrality and standards (Ozias & Godbee, 2011). Neutrality in the writing center can be dangerous especially as staff attempt to make the space welcoming by integrating markers of whiteness and white culture. Eric Camarillo emphasizes this in his article “Burn the House Down: Deconstructing the Writing Center as Cozy Home,” where he asserts that color blindness makes the writing center an inviting and safe space for only white students. Students deserve the ability to challenge “standard discourse” and “the regulatory function of writing centers” (Camarillo, 2019, n.p.). Talisha Haltiwanger Morrisson and Talia O. Nanton’s “Dear Writing Centers” (2020) similarly interrogates whether writing centers are practicing their anti-racist values, arguing that we need to interrogate structural racism and the impact of micro and macroaggressions towards tutors of color on BIPOC practitioners’ well being.

More recent scholarship takes up Ozias and Godbee’s call for more actionable anti-racist praxis in writing centers, including interrogating the politics and stakes of doing racial justice work as accomplices instead of allies (Green, 2016). Wonderful Faison and Frankie Condon’s 2022 edited collection, CounterStories from the Writing Center uses an intersectional feminist framework and counterstory methodology to challenge lore and core assumptions about writing center work, while Talisha Haltiwanger Morrison’s and Deidre Evans Garriott’s 2023 edited collection, Writing Centers and Racial Justice: A Guidebook for Critical Praxis is one of the first to offer clear and actionable guidance on doing racial and social justice work in writing centers. However, even with the proliferation of research about anti-racism in the field, Thompson argues that there is still a dearth of research on how to “operationalize” this work, especially in ways that center peer tutor voices. Thompson further found in a series of interviews with self-described anti-racist tutors that they still frame their work within white discourse (2023). Other scholars, like Kern (2019), have found that tutors resist talking about race and uphold Standard Academic English by teaching others to write as they write. In short, then, there is more work to be done in both articulating what anti-racist praxis looks like in the writing center and how tutors experience being trained in and undertaking this work.

Defining Anti-Racist Tutoring Praxis

Part of the work of creating an anti-racist writing center, for us, was first to develop a common knowledge about the history of writing centers and the power dynamics in the teaching/tutoring of writing. To begin, tutors read about the history of writing centers (e.g., Boquet, 1999; Lerner, 2009; Carino, 1995; Grimm, 2011), as well as the shift, over the second half of the 20th century, from a standardizing and assimilating approach to teaching/tutoring writing to one that offers an asset-based approach to writing where one’s race, class, linguistic background, and other identity markers strengthen student writing and writing process (Flint & Jaggers, 2021; Rhodes, 2022; Shanti & Rafoth, 2009). To facilitate this work, we also read the C’s statement, “Students’ Right to Their Own Language,” the more recent and radical “This Ain’t Another Statement: This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice!,” and resources on enactable anti-racist strategies like code meshing (Isabel C., 2019), code switching, and translanguaging (Choi et al., 2020).

We also examined anti-racist mission statements from other writing centers in order to better understand both the theoretical underpinnings of other centers’ approaches to this work and their mission, goals, and practices. To facilitate our work on mission statements, we collectively read and discussed Asao Inoue’s (2016) “Narratives That Determine Writers and Social Justice Writing Center Work,” which challenges how we define success in the writing center and prompts practitioners to review our mission statements in order to better conceptualize “the frames by which we understand what our work is and how we do it” (p. 96). Together, we then identified what success looks like in our writing center work and ways to facilitate engaging in such anti-racist practices as inclusive pedagogy, writer empowerment, linguistic justice, and emotional support around discussions about race and power dynamics. Part of this work, however, was also taking into account Neisha-Anne Green’s (2018) caution regarding burnout that activists and advocates for racial justice, alongside BIPOC people more generally, experience. To that end, we offered training on wellness that included community and self-care practices alongside fair compensation for training and additional work (Giaimo, 2023). We worked hard, also, to unpack white supremacy culture and whiteness culture (Faison & Treviño, 2017) and how it harms all of us (Okun, 2001).

Below are a sample of the ways in which we envisioned how we will enact the work of an anti-racist writing center. We include the values and practices that tutors and the director collectively created after a year of reading, discussing, and workshopping in order to try to define what an anti-racist writing center looks like (Table 1).

Table 1

An articulation of the anti-racist values and practices of Middlebury Writing Center

| Values | Tutoring Practices |

| Writing Centers are community-focused and encourage writers to connect. When they are at their best, writing centers are also compassionate—rather than disciplinary or punitive—spaces. | We will take non-judgemental and compassionate stances in our tutoring work. |

| Tutoring isn’t a remedial practice—all writers benefit from sharing their writing with others—and in most non-academic spaces, as well as advanced academic spaces, sharing writing and receiving feedback is a critical feature of the writing process. | We will value and honor the role of collaborative and peer learning in our center. |

| We believe our writing center can and ought to push back against the institutional power of the College in order to challenge micro and macroaggressions that students experience in their education. | We will openly discuss social justice issues as they come up in writers’ prompts, essays, and/or writing processes. |

| We value the agency of all writers and aim to empower writers through inclusive and high impact tutoring approaches. | We will be advocates for students, especially in course-based tutoring work. |

| We know that there are many ways to write; therefore, the writing center guides writers in intentionally developing their own writing, rather than solely moving towards the goal of what is conventionally considered “good writing,” which, as many scholars have noted, often perpetuates white supremacist notions of “excellence” in academic writing. | We will empower writers to “take control” of their writing support and education. In other words, we will not edit or write for students. Instead, we will engage with writers in writing activities and discourse with the goal of supporting writers in finding their writerly voices. |

| We recognize that there are disparities in privilege that compound educational access and inclusion and believe writing centers can help bridge those disparities and act as sites of inclusion and access. | We will share what we learn about anti-racism with faculty, even as we also advocate for implementation of anti-racist writing pedagogy. |

| We support writers working in and across a wide array of languages and varieties of English. We legitimize non-standard writing styles/language and a writer’s right to their language(s) and their experiences. | We will work against hegemonic, colonialist, and assimilationist notions of writing education. |

| While tutoring is an example of an educational high impact practice, we recognize that not all tutoring is equally efficacious or impactful; therefore, we are committed to intentional and inclusive program design and implementation. | We will not withhold information from writers. We will provide writers with ways to be more aware of grammar as a set of rhetorical choices with various consequences. |

| We are committed to professionalization and academic training in writing center studies, which prepares us to be reflective, proactive, intentional, and skilled in our tutoring practices. | We commit to continuous learning and evaluating our work in order to improve. |

| We are committed to fair labor practices—which are critical to racial justice. | We pay our tutors for their work (including tutoring, prep-work, scholarship, and professional development). |

Session Notes

Session notes play a key role in our discussion about anti-racist praxis and inclusion efforts. Many of the emotions and perspectives that students bring to a session emerge from traumatic experiences or crises. Students come into sessions looking for answers and are often stressed, upset, or overwhelmed with feelings of insecurity over their assignments. However, even when students are not sharing deep trauma, the act of writing can be profoundly stressful, especially at a highly selective institution with incredible amounts of assigned work. The writing center and its workers operate inside of an institutional pressure cooker. Our research, then, explores session notes for information about how our tutors interact not only with student identities and writing about topics like race and power but also with the affective dimensions of doing such anti-racist tutoring work.

Session notes are an integral part of the writing center. They document tutor practices, reflections, and can be used internally and externally for student growth and development (Dadugblor, 2021). It’s a common practice in our center (as it is in many centers) for tutors to take time after each session with a student (or students) to summarize the work they’ve done in-session and document next steps for the student or use the space for personal reflections (Modey et al., 2021). Historically, this record keeping was used externally for administration and faculty (Pemberton, 1995). Recently, session notes have become a great assessment and research tool within the writing center to prepare tutors for future sessions, analyze moments of conflict, and reflect on tutor praxis (Bugdal et al., 2016; Giaimo et al., 2018; Giaimo & Turner, 2019). While there is growing comfort with sharing session notes, ethical questions about sharing session notes with professors remain. If the writing center is frequently a separate space from the classroom, and its mission involves protecting student privacy and autonomy, then communicating our work to faculty becomes complex and fraught (Pemberton, 1995). The Weaver model takes “a middle road of allowing students the choice of sending notes to instructors“ (Bugdal et al., 2016, p. 17). Our center follows this approach to sharing session notes with external audiences.

In recent years, tutors have become resistant to filling out session notes and view it as a waste of time. A lot of these sentiments come from the belief that there is no one on the other end receiving the session notes and reviewing them–as many students opt out of the Weaver model. As a result, the practice can feel mundane, time-consuming, and almost as if the tutor is being asked to justify their session to the center (Cogie, 1998). To reverse this sentiment, there needs to be more emphasis on the importance of session notes and their role in the writing center outside of faculty review (Gulino & Giaimo, 2023).

Methods

Participants

This study analyzed and coded session notes written by ~40 undergraduate student tutors, from a larger set of notes written by ~90 tutors. Notes were collected from WCOnline over six semesters from Fall 2020 to Fall 2023 at Middlebury college–an undergraduate small liberal arts college with a population of ~2700 students in the Northeastern United States. The tutor population is comprised of undergraduate students who are between their second and fourth year of college; they study in a range of disciplines and are demographically diverse by race and class (60% identify as BIPOC, ~45% as first generation, and 40% as LGBTQIA+), if not by gender (~80% are female identifying). Tutors start their position at the beginning of their second year, after taking either the tutor training course or applying and undergoing intensive summer training. The course and summer training focus on pedagogy work, feedback models, tutor strategy, linguistic justice, translanguage pedagogy approaches, and anti-racist tutoring praxis, including counterstorying. For more information on training, see this guide developed by the director and head tutors as part of the 2020 vision plan work.

In the Fall, the majority of the tutors are embedded in a First Year Seminar where they provide mentorship and writing-based assistance to first year students. Other tutors are paired with a required upper-level College Writing course or work drop-in or online hours. Unlike other tutoring programs at our institution, where the turnover rate is high from semester-to-semester and year-to-year, peer tutors are highly likely to continue their work throughout their undergraduate career, cycling out of the center due to study abroad or graduation. The retention rate, excepting these situations, is 95%; this means that our tutors receive years of standardized training through initial onboarding and new tutor programs as well as through ongoing professional development. About half of the staff also complete a semester-long tutoring writing issues and methods course.

Materials

This study analyzed and coded 5,223 session notes written over 3 years, or six semesters (fall and spring terms, only). After a tutor completes a session, they fill out post-session notes (Table 2), which help the writing center put the session in context and frame the strategies being used. The session notes, as shown below, include guided questions for tutors not only to describe their appointment but also to provide space for tutors to explore unanticipated or complex experiences via the open-ended comments question. Our data for this study was pulled from session notes that responded “Yes” to Question Four, the only checkbox question, and further detailed their experience in Questions Five and Six (Table 2).

Table 2

Detail of session notes questionnaire from the Middlebury College Writing Center

| Question One | Describe the writing/project the writer brought in. |

| Question Two | Describe the writer’s concerns regarding the writing/project. |

| Question Three | Did you share any resources or handouts with the writer? |

| Question Four | Did you engage in anti-racist work (pedagogy, theory, discussion) with the writers in the session? (If “Yes,” please detail in comments below). |

| Question Five | Describe any strategies you utilized with the writer, in-session. |

| Question Six | Open-ended Comments. |

Procedure and Analysis

Session notes were collected from WCOnline over six semesters from Fall 2020 to Fall 2023. In this period, the Middlebury Writing Center had 10,000 sessions, about half of which had attached session notes, resulting in 5,223 sessions for analysis. Of these 5,223 appointments, tutors reported explicitly engaging in anti-racist work in 301 notes, though only 253 session notes shared further textual details. ~6% of session notes referred to anti-racist practice.

We first identified session notes that responded “yes” to Question Four (Table 2) and then reviewed all responses to Question Five and Six to identify any further reference to anti-racist practices. Coding occurred between Summer 2023 and Fall 2024 with an initial review of the notes, and several (4) subsequent coding stages. The researcher and the PI discussed codes throughout the process and determined agreement on definitions and themes (Table 3). Our codes were selected based on recurring themes, identified as academic, emotional, and linguistic justice in relation to anti-racism. The emotional category was further broken down into additional but related subcategories of redirection and reflection (Table 3). A fourth category of “no textual response” was also created to identify tutors who checked “yes” on Question Four but did not include any further details in their notes.

Table 3

Detail of full coding rubric for session notes

| Code | Definition | Examples from Session notes |

| Academic | Any discussion of race, class, or power inequality. The discussion is usually motivated by class material, an assignment/writing prompt, or client’s writing. These notes demonstrate critical awareness and reflection of classroom material and emphasize that discussions of race can be common in the writing center. | We talked about how prejudice in Frankenstein <Academic> translates into prejudice in the real world, and how both mediums have certain correlations in the US education system.

He was focusing his ideas/questions on decolonization <Academic>and what that means, and so we ended up working towards a definition <Academic> and talking a lot about examples and about anti-racism and anti-racist work that goes along with that. We discussed Blackness and the theory of Post-Blackness <Academic> and Post-Black arts, we looked at potential sources for this essay. |

| Linguistic Justice | Discussion that highlights client unfamiliarity with standard academic writing style or conversations that challenge systems of language discrimination. Discussion and tutor strategies normally redirect to confidence building and reassurance. They may identify client vulnerabilities and limitations when writing (with key words such as “professionalism, non-native, multilingualism, grammer) | The more we talked about it the more he wanted instead to talk about academic tone <Linguistic Justice> and then grammar.

She knows she’s capable of writing an engaging essay but smaller things that make an essay formal like grammar and tone <Linguistic Justice> were difficult for her as an ESL student. Session took a bit longer than what I was anticipating because we began to have a more emotionally charged conversation about being ESL and struggling in classes/<Linguistic Justice> with feedback from professors. |

| Emotional | Discussion that centers the emotional and social well-being of the client and may offer reflective notes from the tutor. Conversation may be rooted in themes of identity and personal experiences. Some discussions lead to further direct action such as connecting to other resources. | She was worried about her MED school applications and as a woman of color myself I understood the client’s worries <Emotional>, and we engaged in a discussion in which I tried to relate to her and make her feel heard <Emotional>.

We dove into storytelling and they talked about their family’s migration story <Emotional> starting off with their great grandfather. I felt as if the client, after knowing some of my identities as a first-generation immigrant<Emotional>, was able to elaborate more on their essay and what they wanted out of the session. |

| Emotional <Subcategories> | ||

| Redirection | Reframing conversations or writing that is a micro/macro-aggression about race. Tutor redirection of the conversation or writing to be more inclusive and critically aware of stereotyping and vocabulary choice. | Being intentional in talking about marginalized people <Redirection> other than POC – Inputting more personal thought on the other prompt questions What is justice…Can true justice ever be achieved?

We chatted about the use of “slave” vs enslaved people <Redirection> and how that change in vocabulary shifts the power hierarchy. Sweeping generalization can further marginalize already-marginalized communities, and I tried to explain that casually. I didn’t want to make her feel like I was accusing her of being inconsiderate or ignorant, just letting her know that there can be important connotations that underlie word choice <Redirection>. |

| Reflective | Reflective statements that tutors make specifically about themselves and their engagement during the session; they may identify limitations or successes of their tutoring approaches or regarding their ability to address or handle the writing prompt/assignment. | Reflecting back on what I saw <Reflective> working with students on the first assignment and primarily how much more work (female/) students of color had to do in engaging with the prompt compared to others in the class.

She said that she had never considered herself a good writer. I sympathized with her as I remember <Reflective> feeling the same way entering college. I was privileged enough to be able to admit my lack of skill and ask for help without fearing excessive judgment. |

Results

The practice of writing session notes was new to the Middlebury writing center as of 2020. Only a semester prior (Fall 2019), the center had migrated to WCOnline from a combination of paper form and Google form record-keeping. Although it is required for tutors to complete session notes, the completion rate hovers around 50%, and, lately, it has been dropping (~30%). As part of their onboarding, all tutors undergo a 1 – 2 hour training where they review past session notes, code notes for thematic, affective, and key terms, and discuss the purpose of these notes. Session notes are a main driver of our internal assessment, so we also refer to them in other training, such as on role conflict and politeness, counterstorying (Martinez, 2020), and emotional labor. Therefore, tutors are trained in writing detailed and discursive session notes that include reflection of tutoring strategies and practices, and are routinely reminded to complete session notes, yet the practice of completing notes is uneven. There is also a wide variety in the response styles and lengths of session note responses with some tutors writing only a descriptive sentence or two about their practices and others writing up to a paragraph or more (~150 words) about what took place in the session. The notes often have very little detail beyond the checked box indicating completing a specific tutoring practice like anti-racist pedagogy.

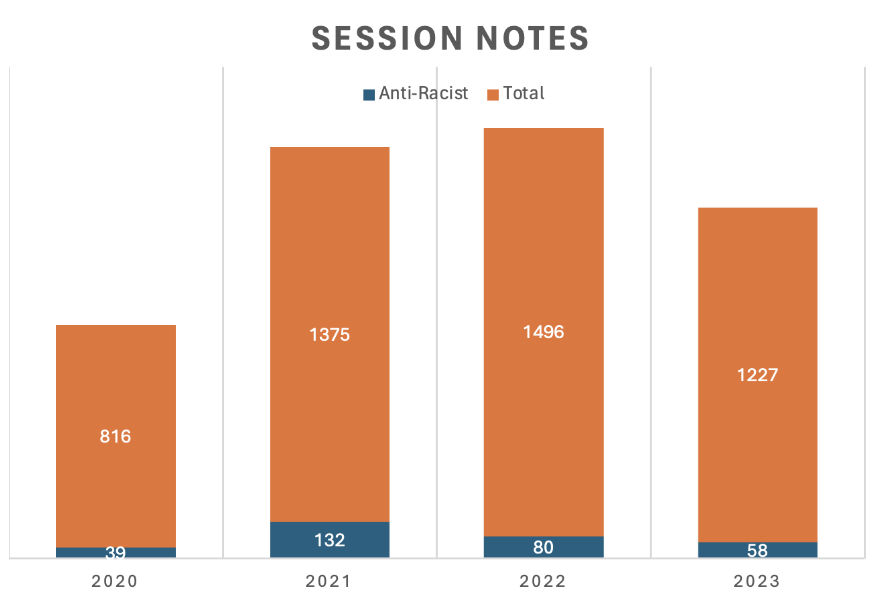

Figure 1. Figure showing the number of completed session notes per year from 2020 to 2023, differentiating between total number of session notes and those focused on anti-racism praxis.

In coding and analyzing session note responses from Spring 2020 to Fall 2023, we found that 2021 had the highest response rate for reported engagement in anti-racist tutoring practices (Figure 1). In subsequent years, there has been a gradual but observable decline in the number of tutors reporting engagement with anti-racist practices in their session notes. Despite strong tutor advocacy for the writing center to adopt anti-racist practices, the session notes show low reportage of tutors using these practices in their work, with a gradual decline in response rates on this topic starting after 2021 (Figure 1). There is a change from a ~10% response rate in 2021 to ~5% in subsequent years. Further, 65% of session notes on anti-racism were written by BIPOC tutors while 35% were written by white tutors. Of the white tutors who wrote about anti-racist tutoring practices in their notes, 65% identified as LGBTQIA+.

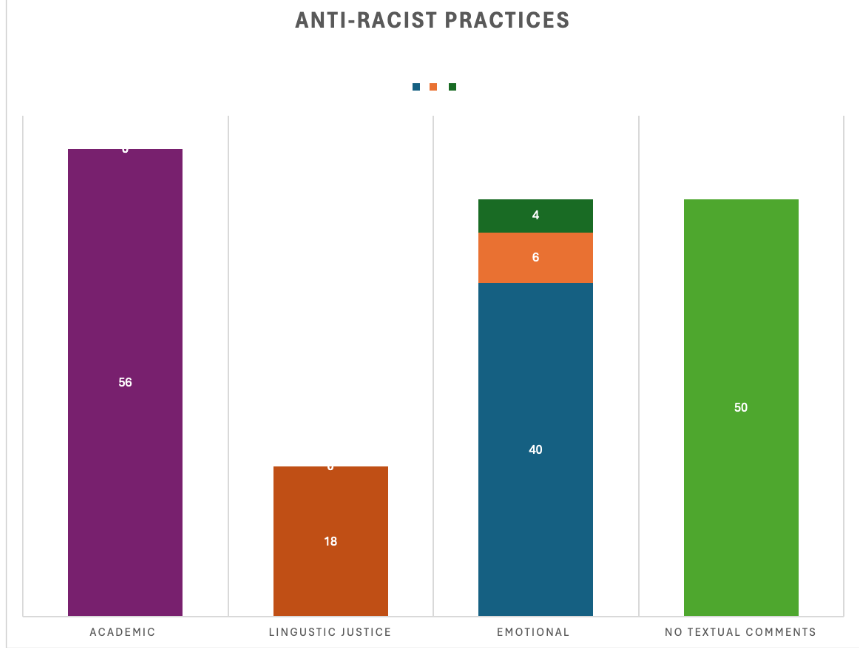

Figure 2. Figure showing the breakdown of session notes coded by specific themes (academic, linguistic justice, emotional, and no textual response). The emotional category includes writer-based emotional support (40), as well as two subcategories related to tutor emotional labor including redirection (4) and tutor reflection (6).

The notes were coded by four categories: Academic Support, Linguistic Justice, Emotional Support, and No Textual Comments (Figure 2). Academic support is the most common way in which tutors reported engaging in anti-racist practices; this approach involves tutors working through assignment prompts that include issues of power and race. The tutor engages actively in these conversations with the writer through cuing and question prompting on these topics (Table 3). Emotional support regarding anti-racism (we only focused on notes identified as engaging in anti-racist praxis) is the second most common way that tutors report engaging in anti-racist practices with their writers. This approach includes several sub-approaches which can be described as emotional support for the writer around issues of racism and identity-related challenges, tutor self-reflection on issues related to race, and tutor redirection of harmful and racist language. Linguistic justice–the least-occurring category–is one in which tutors addressed the intersection between race and language support, such as normative writing feedback, lower order concerns, and linguistic justice. Finally, notes that did not have any follow-up comments were coded as a fourth “no comments” category.

Discussion

Explaining the Session Notes Trends

The response trend might follow national events that impact engagement in anti-racist work. For example, low reported engagement in 2020 was expected because of the unfamiliarity with the training and the impacts of COVID-19 which shifted tutoring to online platforms. In 2021, the writing center shifted back to an in-person model during a time when students were pushing for institutional spaces like the writing center to engage in anti-racism. Then, there is a decline in reported engagement in this work which coincides with the backlash against social justice work and DEI initiatives, nationally. At the same time, this trend also reflects the “lifecycle” of a tutor (who works on average for 2.4 years with the writing center). Here, we see a groundswell of advocacy to do this work in 2020 – 2021, a height of reported engagement in 2021, and a decline in 2022 and 2023. Many of the peer tutors who spearheaded these efforts graduated in 2022 – 2023, thereby causing a culture shift that was further uncovered in our 2023 listening session where newer tutors disclosed reluctance to do anti-racist work.

Of the notes analyzed, we see trends where tutors more readily name anti-racist praxis such as in the academic code. Tutors noted that students were coming into the writing center with an agenda to talk about race in the context of their classes and the world. Margaret, a white tutor, wrote, “He was focusing his ideas/questions on decolonization” and David, another white tutor, emphasized, “We talked about how prejudice in Frankenstein translates into prejudice in the real world.” In 2021, especially, students and tutors alike were excited and open to conversations about race, prepared to connect classroom knowledge and personal experiences. As we detail below, however, in the intervening years, there have been direct national and local attacks on DEI work and anti-racism that might have had a chilling effect on tutors’ reportage of engaging in such topics in session notes. Similarly, course curriculum might have been impacted by anti-DEI policies being instituted in higher education and other spaces around the United States.

Another main finding, however, is that, even when anti-racism was a topic routinely discussed across our campus, we found that predominantly BIPOC, queer and trans, and other marginalized tutors reported engaging in these practices. Below, we share session notes from 10 different tutors; six identify as white and four as BIPOC, while half identify as queer. Tutors who report engaging in anti-racist practices tend to hold similar identities to their clients and use that as a bridge to talk about race and shared experiences. Our challenge here is ensuring that the emotional aspect of this work is upheld by all tutors and not only BIPOC or queer tutors. To push for open and vulnerable conversations about identity among tutors who are white, we turn to Talisha Haltiwanger Morrisson and Talia O. Nanton’s “Dear Writing Centers” (2020), in which Nanton shares experiences with racism and the emotional toll of working in a hostile and overtly racist and sexist work environment. In the article, the authors provide an excellent framework for how to move from silence into action as white tutors and administrators, which includes changing training and hiring practices, remaining open to feedback, “conducting a case-study on your center’s “safe-ness,’” along with “drawing on the voices and experiences of tutors of color to inform the practices and scholarship of our field” and co-writing with colleagues of color. In this way, both decentering whiteness–insofar as allowing it to uncritically drive the day-to-day functioning of a writing center–and interrogating “echoes of whiteness” (Faison & Treviño, 2017) in tutor praxis are ways to create a welcoming, yet critical space that examines implicit whiteness and undertakes reflective and investigative work about race.

Our listening session also found that tutors struggled with naming their work as anti-racist if they’re not explicitly working with a writing prompt that has themes of racial injustice. Several tutors worried that incremental work on the topic of race and belonging wasn’t “big enough” to “count” as anti-racist. The challenge we’re facing is breaking the misconception that anti-racist work has to “solve” inequity to be meaningful. This work, then, requires us to un-learn perfectionism and “getting it right” immediately, as well as creating space for identity-based exploration and reflective work for new tutors. It is hard to maintain the momentum of grassroots justice initiatives in writing centers.

Academic Support

The most common way our tutors report engaging with anti-racist practices is through academic support. This describes writing prompts or assignments that have themes of injustice, race, or identity. The reason for this is because tutors are more likely to engage in anti-racist practices when given guidance within a session. This guidance normally comes from the assignment prompt or questions that the student has for the tutor. As Margaret wrote: “He was focusing his ideas/questions on decolonization and what that means, and so we ended up working towards a definition and talking a lot about examples.” Bella a white queer tutor wrote:

[The] client wants to discuss intersectionality as it is related to race and queerness in their essay. Discussed the importance of noting the impact of race in queerness, especially noting how white queer folks have been historically privileged in the queer liberation movement.

In both of these examples, the student came into the tutoring session looking to have a conversation with a tutor to talk through their ideas about race and power in relation to their essay. This appears to be an easier path for tutors to follow than for them to initiate conversations about race within sessions that are emotionally charged. Tutors also have an easier time defining this as anti-racist work because of the clear guidelines and promptness, unlike emotional support which can be a gray-area for tutors.

Emotional support

Emotional work is the second largest category of anti-racist practice that tutors perform; it is also the one that BIPOC tutors more consistently report engaging in, despite training that asks white tutors to step into these conversations more intentionally. In session notes, tutors report utilizing their anti-racist practices to engage with the emotionality of a writer or navigate through writing that involves identity and personal experiences. This is where tutors often engage in affective connection with the writer and empathy building, especially within first year writing courses, where mentorship is an integral part of the tutor role. Elijah, a BIPOC, First-gen, queer tutor wrote: “I felt as if the client, after knowing some of my identities as a first-generation immigrant, was able to elaborate more on their essay and what they wanted out of the session.” Nancy, another BIPOC queer tutor, wrote: “She was worried about her MED school applications and as a woman of color myself I understood the client’s worries.” Here, both tutors see their identities as an important element of facilitating the tutoring process. Elijah was able to build a shared connection with the first-year writer through acknowledging their first-generation and immigrant identities whereas Nancy builds a shared connection, as well as empathy, with their client as they apply to medical school.

Though BIPOC tutors are not asked to bring their identities to the table in tutorials–we do not, for example, ask tutors to showcase their identities as a way to build mutual understanding as BIPOC people are relied upon to “teach” others about their experience and identities–here, the tutors have a chance to reflect on how shared experiences and mutuality as well as empathy building (in Elijah’s case with the writer and in Nancy’s case with the tutor) help facilitate the process in the tutorial nonetheless.

Reflective

Reflective session notes make up a small subset of emotional anti-racism work. This type of session describes a reflective post-session debrief about the effectiveness of the session, overarching commentary, or conflict that arose. The majority of tutor reflections were written by white tutors who were reflecting on their own privilege after a session and embracing feelings of discomfort.

Cynthia, a white tutor, wrote, “Reflecting back on what I saw working with students on the first assignment and primarily how much more work (female) students of color had to do in engaging with the prompt compared to others in the class.” Here, the tutor is reflecting on the impact of the prompt given by the professor and noticing how different demographics of students interact with classroom material. This could be potential feedback that the tutor relays to their Professor or an experience they can bring with them to the next tutor training session. Kevin, another white tutor, reflected, “She said that she had never considered herself a good writer. I sympathized with her as I remember feeling the same way entering college. I was privileged enough to be able to admit my lack of skill and ask for help without fearing excessive judgment.” The tutor was able to sympathize with the student because of their shared experience, and they were able to acknowledge the uncomfortable feelings of judgment and fear that can be associated with asking for help.

These reflections further emphasize the importance of anti-racism training and the rationale for educating tutors about why we should continue educating tutors about cultures of whiteness in the writing center. We want to expand the ability of tutors to connect with different writers and accommodate their identity into the writing session instead of pretending their identity doesn’t hold weight in their writing.

Redirection

Redirection occurs when a tutor is engaging with a student that is committing a micro or macroaggression against a marginalized community, either vocally or in their assignment, and and redirecting them and reframing the conversation to be more inclusive. Oftentimes students don’t recognize when their vocabulary or their lack of a wider perspective is hurting a community or projecting a stereotype.

As noted by Lilly, a BIPOC and queer peer tutor, “Being intentional in talking about marginalized people other than POC – Inputting more personal thought on the other prompt questions What is justice…Can true justice ever be achieved?” Lilly noticed that the student’s writing was leaning towards a white savior complex, and they wanted to redirect the student to write from personal experiences and widen their perspective on the prompts. They addressed this microaggression by encouraging the student to engage with other parts of the prompt and asking questions. Mary, another BIPOC peer tutor said, “We chatted about the use of “slave” vs enslaved people and how that change in vocabulary shifts the power hierarchy.” Mary used a direct approach and highlighted the power difference between the language being used. This approach is less commonly used by tutors because it can be uncomfortable to point out and address. Usually, students come to get their papers and assignments read for lower order concerns like grammar or the more nebulous “flow” related to writing structure, and the tutors take the extra step to pause the session and kindly, but intentionally, point out harmful vocabulary.

Linguistic Justice

The least common way our tutors report engaging with anti-racism practices is through addressing linguistic support and race, or linguistic justice. The session notes amplify that when working with multilingual writers, there is an underlying emotional support of confidence building and reassurance. Kevin also wrote: “She knows she’s capable of writing an engaging essay but smaller things that make an essay formal like grammar and tone were difficult for her as an ESL student.” Sarah, a white and queer head tutor, wrote: “Session took a bit longer than what I was anticipating because we began to have a more emotionally charged conversation about being ESL and struggling in classes with feedback from professors.” Here, both tutors bring linguistic identity into their reflection on their sessions. In the latter note, however, Sarah needed to dedicate more time to the writer to engage in the emotional elements of receiving difficult feedback from professors. Kevin discusses the multilingual writer’s confidence level and structural needs as they navigate writing in Standard Academic English. Emotional support, then, is an integral part of anti-racism work, particularly as it relates to linguistic background and one’s identity. Here, we see the tutors trying to create space for vulnerable conversations even as they support the students’ writing processes and rights to their own languages.

Conclusion

From observing the low percentage of session notes that address anti-racist keywords and themes, as well as our listening session in fall 2023, what comes into relief is that tutors report using anti-racist strategies in particular ways and often are affected by the emotional labor. However, white tutors have noted that they struggle to initiate conversations about race within sessions and in training, which tracks with our finding that session notes engaged in anti-racist work were overwhelmingly written by BIPOC tutors (65%). This is challenging because anti-racist work involves a heavy amount of emotional labor to support other students through their writing process and that labor ought to be more evenly distributed among the staff, not just marginalized tutors. Our goal is to nurture conversations about race and racism in training to prepare tutors to engage in this work during their sessions, yet, given our assessment of tutor session notes, we wonder what barriers are there to engaging in this work for our tutors?

In part, we believe that the work that a student brings into the writing center equally matters to upholding anti-racist practices. Students and tutors alike need to have other opportunities outside of the writing center to critically engage with issues of race and identity. Initially, our college was engaged in such conversations, but both authors have noted a drop-off in college-wide conversations about race and language justice. The ongoing humanitarian rights abuses in Ukraine and Gaza add further international emphasis on race, religion, and national identity as compared to a more local and domestic focus on race and belonging during the height of BLM protests. Further, national and more local attacks on DEI work in higher education (Gretzinger & Hicks, 2024), including the shuttering of DEI initiatives (Kennedy, 2024), the scrutiny or outright culling of diversity-focused curricula (Quinn, 2024), and the many multipronged attacks on DEI and social justice work in educational institutions (“The Assault on DEI”) around the United States add to the chilling effect on such local initiatives.

Though Middlebury College is a private institution, we have seen many such private colleges called to Congress to account for social justice activities over the last year. Closer to home, writing centers around the country have been challenged in their DEI efforts, including having right-wing media attack gender neutral statements and policies (Targ, 2018) or DEI work; such attacks are likely to accelerate as we move into an election year. At our own institution, as we detailed at the beginning, a small but very vocal minority of faculty challenged the writing center’s anti-racist pedagogical focus and demanded changes to our internal session note form; this conversation rose to the level of a departmental conversation and a conversation with senior administration, including the Provost of the College. The second author of this article was also asked if they “discriminate against white male students,” in their hiring process. Here we see traces of institutional hostility to anti-racist writing center training and reportage as well as hiring practices. To imagine such national and local challenges to social justice work does not have an impact on our critical discourse around race and belonging then would be naive at best.

This leaves us with an uncomfortable and incomplete ending, especially since Genie–the Director of the writing center–will be leaving the institution for a more stable tenure track position in August, and Sheila will be graduating in a year. We agree that the writing center cannot be the only academic space doing anti-racist pedagogical work on campus. For one, this makes the writing center a target for different kinds of internal and external smear campaigns about the work that we do. Furthermore, it places the onus on contingent workers like peer tutors and contingent writing center administrators to do this work day-in and day-out in a highly stressful and privileged space that has profound inequalities built into its culture; our institution has one of the largest number of students from the top 1% of income earners in the U.S. (The Upshot, 2017). Additionally, it places a lot of responsibility on the writing center to carry forward ethical practices that might come at the expense of the good faith actors engaging in this work. Of course, we hope that the writing center will be an inclusive space where students from all different backgrounds come in for empathetic support, but educating students about racial injustice or guiding students who are experiencing such racial injustice in their education can be deeply isolating if it is not supported by other stakeholders in the institution. Additionally, the annual decline in tutors reporting anti-racist praxis on session notes, coupled with the majority of tutors who do report doing anti-racist work being marginalized themselves, suggests that more work should be done to prepare white tutors to do this work. BIPOC and queer tutors should not carry the weight of this reflective, affective, and academic work, even if they are particularly impacted by racism and other intersections of injustices.

Despite our misgivings, and our findings that our training yielded more complicated outcomes in terms of tutors reporting engaging in anti-racist praxis in their work, we still believe in making writing centers sites of inclusion and advocacy on campus. In our research, we have found that centering anti-racist praxis in our trainings and missions did impact the work of the writing center and shift the culture on our campus. The writing center also provided a space on campus where students and tutors hungry to talk about race and power would find sympathetic and empathetic listeners. While not enough, not by a long shot, it is more than what we previously had at our writing center. This, in the end, is what matters; the incremental changes one program can make to an institution. We hope future research will continue to study how DEI efforts, inclusion work, and anti-racism are enacted in and through the writing center but, also, work that responds to the chilling effect on this work which is happening around the United States in Higher Education.

References

Boquet, E. Our little secret: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463-482.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth, B. (2009). ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors. Heinemann.

Bugdal, M. et al. (2016) Summing up the session: A study of student, faculty, and tutor attitudes toward tutor notes, Writing Center Journal: 35(3), 13-36. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1840

Camarillo, E. C. (2019). Burn the house down: Deconstructing the writing center as cozy home. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/burn-the-house-down-deconstructing-the-writing-center-as-cozy-home/

Carino, P. (1995). Early writing centers: Toward a history. The Writing Center Journal, 15(2), 103–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43441973

Choi, J. et al. (2020). Introduction to the special issue: Translanguaging as a resource in teaching and learning. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v3n1.283

Cogie, J. (1998). In defense of conference summaries: Widening the reach of writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 18(2), 47-70. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1400&context=wcj

Dadugblor, S. K. (2021). Collaboration and conflict in writing center session notes. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 18(2). http://www.praxisuwc.com/182-dadugblor

Faison, W. & Condon, F. (Eds.). (2022). Counterstories from the writing center. University Press of Colorado.

Faison, W. & Treviño, A. (2017). Race, Retention, Language, and Literacy: The Hidden Curriculum of the Writing Center. The Peer Review, 1(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/race-retention-language-and-literacy-the-hidden-curriculum-of-the-writing-center/

Flint, A. S., & Jaggers, W. (2021). You matter here: The impact of asset-based pedagogies on learning. Theory Into Practice, 60(3), 254-264. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1305357

Green, N. A. S. (2016). The re-education of Neisha-Anne S Green: A close look at the damaging effect of “A Standard Approach,” the benefits of codemeshing, and the role allies play in this work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 72 – 82. https://www.praxisuwc.com/green-141

Green, N. A. (2018). Moving beyond alright: And the emotional toll of this, my life matters too, in the writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15-34.

Giaimo, G. N., & Turner, S. J. (2019). Session notes as a professionalization tool for writing center staff: Conducting discourse analysis to determine training efficacy and tutor growth. Journal of Writing Research, 11(1), 131–162. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2019.11.01.05

Giaimo, G. N. et al. (2022). It’s all in the notes: What session notes can tell us about the work of writing centers. The Journal of Writing Analytics, 2, 225– 256. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/jwa/vol2/giaimo.pdf

Giaimo, G. N., & Gulino, J. (2023). Communicating work-related conflict: textual analysis of politeness strategies and linguistic cues in tutor session notes. The Peer Review, 7(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-7-2/communicating-work-related-conflict-textual-analysis-of-politeness-strategies-and-linguistic-cues-in-tutor-session-notes/

Giaimo, G. N. (2023). Unwell writing centers: Searching for wellness in neoliberal educational institutions and beyond. University Press of Colorado.

Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (2011). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. Utah State University Press.

Gretzinger, E. and Hicks, M. (2024, June 28). Tracking higher ed’s dismantling of DEI. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/tracking-higher-eds-dismantling-of-dei?utm_source=Iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=campaign_10047309_nl_Academe-Today_date_20240604&cid=at&sra=true

Grimm, N. M. (2011). Retheorizing writing center work to transform a system of advantage based on race. In L. Greenfield & K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change (pp. 75–100). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk6s.8

Haltiwanger Morrison, T. & Evans Garriott, D. (eds.) (2023). Writing Centers and Racial Justice A Guidebook for Critical Praxis. Utah State UP.

Isabel, C. (2019). Creating conversation: Code meshing as a rhetorical choice. UCWbLing. https://ucwbling.chicagolandwritingcenters.org/creating-conversation-code-meshing-as-a-rhetorical-choice/

Inoue, A. B. (2016). Afterword: Narratives that determine writers and social justice writing center work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 94-98. https://www.praxisuwc.com/inoue-141

Kennedy, J. (2024, May 31). Students left unsure about future of UT as DEI programs go away. CBS Austin. https://cbsaustin.com/news/local/students-left-unsure-about-future-of-ut-as-dei-programs-go-away

Kern, D. S. (2019). Emotional performance and antiracism in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2), 43-49. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/f3c73545-8df1-4948-ab90-94fa49b7bdff/content

Lerner, N. (2009). The idea of a writing laboratory. SIU Press.

Martinez, A. Y. C. (2020). Counterstory: The rhetoric and writing of critical race theory. National Council of Teachers of English.

Modey, C. et al. (2021). Session notes: Preliminary results from a cross-institutional survey. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 18(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/183-modey-et-al

Morrison, T. H., & Nanton, T. O. (2019). Dear writing centers: Black women speaking silence into language and action. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/dear-writing-centers-black-women-speaking-silence-into-language-and-action/

Okun, T. (2001). White supremacy culture. In K. Jones and T. Okun (Eds.), Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups. https://www.thc.texas.gov/public/upload/preserve/museums/files/White_Supremacy_Culture.pdf

Ozias, M., & Godbee, B. (2011). Organizing for antiracism in writing centers: Principles for Enacting Social Change. In L. Greenfield & K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing Centers and the New Racism: A Call for Sustainable Dialogue and Change (pp. 150–174). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk6s.11

Pemberton, M. (1995). Writing center ethics: Sharers and exclusionists. Writing Lab Newsletter, 20(3), 13-14. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v20/20-4.pdf

Rhodes, R. (2022). Investment and praxis in asset-based assessment: Exploring transnational identity and perspectives for academic english writing pedagogy. In O.Z. Barnawi et al. (Eds.), Transnational English Language Assessment Practices in the Age of Metrics (pp. 153-168). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003252382

Statement on anti-racist and social justice work in the Middlebury writing center. (2020, December). Retrieved from https://www.middlebury.edu/sites/default/files/2021-01/Statement%20on%20Anti-Racism%20and%20Social%20Justice%20Work–Middlebury%20Writing%20Center.pdf

Targ, H. (2018, March 5) Letter: Why did Purdue let fox news push university around on writing guidelines? Journal & Courier. https://www.jconline.com/story/news/opinion/letters/2018/03/05/letter-why-did-purdue-let-fox-news-push-university-around-writing-guidelines/394666002/

The Assault on DEI (2023). The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/package/the-assault-on-dei

The Upshot (2017, January 18). Some colleges have more students from the top 1 percent than the bottom 60. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/01/18/upshot/some-colleges-have-more-students-from-the-top-1-percent-than-the-bottom-60.html

Thompson, F. (2023). “How to play the game”: Tutors’ complicated perspectives on practicing anti-racism. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 21(1). https://www.praxisuwc.com/211-thompson

Quinn, R. (2024, March 18). Virginia officials scrutinize two universities’ DEI course syllabi. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/diversity/2024/03/18/va-officials-scrutinize-2-universities-dei-course-syllabi

Villanueva, V. (2006). Blind: Talking about the new racism. The Writing Center Journal, 26(1), 3–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442234