Liz A. W. Thomae, St. John’s University

Aleena A. Jacob, St. John’s University

Abstract

This article offers a narrative account of how we, graduate assistants at a private, Vincentian university writing center, confronted and addressed sexual harassment within our space. Beginning in the spring semester of 2022, we saw an increasing number of sexual harassment incidents in our writing center. Desperately searching for more effective practices to protect our consultants and clients alike from these experiences, we drew inspiration from Kovalik et al.’s (2021) concept of a community contract, developing a contract tailored to the specific needs and dynamics of our writing center environment. By recounting our experiences, this article highlights the challenges faced by the consultants we mentor when dealing with harassment in their workplace, as well as how we balance policy and agency when looking for a solution. There is little literature currently on sexual harassment in writing center scholarship, so it is our hope that our experiences will inspire future research as well as fill some existing gaps in the academic landscape. We conclude this essay by reflecting on the outcomes of our initiatives and the lessons learned in the process. We hope that this framework will prove valuable to other writing centers currently dealing with similar problems, and that by implementing a community contract, writing centers may preemptively avoid such situations.

Keywords: student misconduct, sexual harassment, community contract, writing center policy

“Hey, you’re pretty for a brown girl.”

We quickly learn as writing center consultants that one unanticipated comment can throw off an entire session with a student, no matter how well the session had been going before. This becomes even truer when it comes to unwarranted sexual advances, observations about one’s identity, or illicit, uncomfortable conversation topics. This was true for Maya,[1] a senior writing consultant at our center. The session began as most do, exchanging pleasantries, ensuring that the student-client is comfortable, and determining how the next 45 minutes will be best spent. It was not until a few minutes into the session that her client, a white, male peer, derailed the focus of the session with one comment: “Hey, you’re pretty for a brown girl.” In this moment Maya, taken aback, must take stock of her positionality, the student-client’s positionality, what is at risk, and her own emotions, and then determine how to move forward. Does she address the inappropriate nature of this comment? Does she smile and brush off the affirmation of colorism, moving the session forward? Does she find a graduate assistant or another leader in the writing center and escalate the matter higher? In mere seconds, Maya must navigate an unfair and unjust situation with the means available to her. Though there may be resources available and support surrounding her, at this moment it is very easy for her to feel alone, targeted, unsafe, and unsure.

Unfortunately, situations like these are not uncommon. The Association of American Universities (2019) found that on college campuses, 59.2% of women experience some degree of sexual harassment during their time at the university (p. viii). While there is not enough definitive research to confidently assert that these staggering statistics are reflected in writing center spaces, it is clear to those working in these spaces that some level of harassment is making its way through the writing center’s doors from the campus at large. We have found this true in our own writing center especially, a writing center at a private Vincentian university, with the rates of student misconduct growing exponentially in the two semesters following the height of the Covid-19 pandemic (namely Spring 2022 and Fall 2022). From racialized comments like the one Maya endured to inappropriate gestures during consultations, from clients derailing writing conversations in order to ask for consultants’ phone numbers to severe incidents of stalking, our writing center has been the background for an array of concerning incidents.

As we saw the number of weekly incidents rising, we questioned how to move forward and what the best practices were to keep our consultants safe while maintaining the “homey” and welcoming feel we, and many other writing center administrators, desire our writing center to emanate, for better or for worse (McKinney 2013). The way forward was a journey for us, a journey on which we hope many more writing centers will join, as the work is nowhere near its endpoint. With this goal in mind, in this paper, we will discuss our lived experiences in our writing center as graduate assistants through a narrative format and the way we handled the threat of sexual harassment in our space. We share our collaborative process of creating a community contract for our writing center and offer the final version as a foundation for others to build upon. We create a framework that balances student agency and autonomy with necessary, protective policy that can easily be adapted by other writing centers negotiating their way through the muddy waters of student misconduct in their space. We believe that our work bridges gaps in existing research by demanding an intellectual consideration of sexual harassment in writing centers as a focal issue within student misconduct, something that desperately needs recognition within this field.

Our Stories: How Far is Too Far?

We both work at our writing center as graduate assistants, so we are invested in the day-to-day operations of our center as leaders.[2] We toggle between our identities as administrators, mentors, and students, and this gives us a complex and unique perspective from which we conduct our leadership.[3] We see what is going on from a higher level– we know what needs to happen from an administrative point of view, what kind of training needs to happen, and how to keep the center running smoothly. But we also see how the job affects our undergraduate consultants in a very real way as we are “in the weeds” with them.

Our campus is diverse in race, religion, gender identity, sexuality, economic backgrounds, and more. With this diversity at the forefront, we want our center to be a place that celebrates it, that champions students’ voices, and that feels like a safe space. When we started to notice that some sessions were impacting the space in a negative manner – for both consultants and for clients – we responded as both peers and student-leaders. Because of our unique position as graduate assistants, in many cases, we either saw or heard the incidents that occurred in our space, or were notified shortly after. Additionally, because we share close relationships with both the writing center’s director and assistant director, we felt empowered to act on behalf of our staff while knowing we were fully supported from above. While there were an alarming number of incidents, we have chosen to highlight the three that, along with Maya’s story, exemplify the crux of the issue at hand: blatant entitlement.

Creepy and Entitled Behavior

In the spring semester of 2022, our campus was slowly transitioning back to its pre-Covid status quo. Masks were no longer required, distancing was loosened, and students were opting, once again, for in-person classes. This also meant that the writing center experienced higher traffic than it had in over a year, bringing in new students every day. One of these students was Arthur, a nontraditional student who frequented the center daily. At first, consultants found him a bit creepy but had difficulty articulating why. He had a certain suspicious demeanor about him, and many interactions with him seemed off-putting. He would lurk about the center, even if he did not have appointments, and began to make certain consultants uncomfortable with his presence. He had the tendency to “sneak up” on consultants and startle them when he wanted to ask a question and had little to no awareness of personal space. He acted as if the writing center was his alone, to the point that many consultants acknowledged that they felt that they no longer had access to their own workspace.

As his behavior began to worsen, consultants took note. Many refused to be in spaces near him, and others requested to not work with him. When he would make appointments, he refused to make them himself online (as is our center’s policy) but would wait by our front desk until a female staff member was working there and then insist that that staff member make an appointment for him. Similarly, he would consistently book sessions only with our women consultants and come unprepared with no clear goals, thereby putting extra work on our consultants to direct a session that had no inherent direction. Often, he would also demand that these consultants do tasks outside their responsibility, such as plugging in his laptop for him. In one specific instance, one of our strongest and boldest consultants attempted to terminate the session after he presented no assignment to work on; this resulted in his refusal to leave and an attempt to cause an angry scene, demanding to speak to our director (also a woman). After this incident, we asked Arthur to leave our space and deactivated his account on our scheduling platform. He attempted to return in the fall of 2022 and, once again, put up quite the fight with our director, but we were able to stand our ground to ensure the safety and comfort of our consultants. We hoped that this was a one-off incident, but we were sadly mistaken. Our situation with Arthur only seemed to begin an influx of these types of events, heightening our awareness as leaders.

Stalking

In the fall semester of 2022, incidents began to increase both in intensity and number. Lauren, a senior consultant, came to us to report unwelcoming and hostile incidents with a client who happened to be a co-worker in her other campus job as a resident assistant. This co-worker had crossed boundaries multiple times outside of the space, including an instance where he refused to leave her dorm room. This particular client began making appointments with Lauren and usually did not convey clear goals or a specific assignment to work on. Other times, he would neglect bringing in any kind of writing assignment at all; he made appointments simply to chat with Lauren as his consultant. The advances he made during these types of sessions were unwanted and unencouraged, and altogether made Lauren feel unsafe.

To address these incidents, we began by simply moving his appointments to other consultants. The student became apoplectic at the thought of his appointments being moved and complained to both the director and assistant director of the writing center, both of whom kindly explained the policy behind their decision. He responded that working with Lauren was a “clear right” as he pays tuition money that funds the center, and by that logic, funds his access to Lauren’s person. The disturbing nature of his presumptuous ownership over Lauren, a black woman, was made further alarming by their racial identities: as a white man, this client’s rhetoric embodied the financial entitlement that has historically commodified black women’s bodies and their labor. His response to our administrators demonstrated the full extent of his assumed privilege to consultant access, time, and intimacy of the consultation space in the center, a notion that we found to be increasingly shared by a vast number of the student population that utilized writing center services. At the same time, the student began to show up in Lauren’s place of residence, unexpected and unannounced. Because of the nature of these advances, the matter had to be reported institutionally with the Title IX office. This student had access to both of Lauren’s places of work, one of which was also her home as an RA. The harassment cornered her in almost every aspect of her daily life, causing distress and questioning/jeopardizing her safety. We wondered if working with a specific consultant truly was a “right,” and if any codes of conduct existed that would suggest otherwise, but our search into this matter institutionally came up empty, prompting us to fill the gaps.

Alarming Subject Matter

During the evening hours at our writing center, a student came in with a creative short story he wanted to get an opinion on. Once again, Lauren was the consultant for this particular session, and by this time, had unfortunately become accustomed to working through difficult sessions. The session began normally, and the story seemed innocent at first. It followed a budding college romance in the residence halls, but the story took a dark turn when the plot morphed from romance to murder. The story specifically explained in detail how the main character kills his love interest, proceeds to rape her inside their residence hall, and later eats her. Reaching this point in the story, Lauren became increasingly uncomfortable and excused herself to alert one of us and asked how she should move forward. At our writing center, we, of course, encourage writings of all types and typically instruct our consultants to help clients even if they disagree with the viewpoints being articulated as it can be a good chance for education and for changing the rhetoric surrounding oppression (Suhr-Systma & Brown, 2011). It is also the responsibility of both the reader and writer to authentically respond (Elbow & Belanoff, 1999). However, with the explicit nature of this story and Lauren’s clear uneasiness, we made the decision to shut down the session. When we explained this to the client, he stated that “he had the right to bring in whatever he wanted ” and work with whomever he likes. We wondered how far is too far with writing, what consultants actually consent to as they enter a session, and how much we can actually protect our consultants from uncomfortable situations.

The Foundations for Our Solution

We share these stories to paint a realistic picture of our writing center and to express the urgency we felt to “deal” with the problem. Stories have a unique way of drawing storyteller and listener together into a relationship, even if temporarily; the hardships faced by one will by proxy be felt by the other (Dixon 2017). With this in mind, we invite you into the weeds of our writing center and share with you our collaborative process for overcoming the sexual harassment we saw.

With our consultants’ safety risk increasing simply by existing in our space and doing their job, we knew we had to find a new way forward as leaders. To begin, we borrowed Dixon’s (2017) framework of accepting the messy, everyday parts of writing center work as integral to what we do. Rather than looking at these incidents as something to overcome, move past, and forget for the sake of trying to create an idealistic – yet unattainable – space, we addressed the discomfort these incidents left behind. In her research on queering the everyday of writing centers, Dixon (2017) suggests that negotiating sexual harassment and other incidents comes from working through unsettling events and asking how they “complicate our understanding of what it means to make meaning in the center.” In our case, what do these new levels of harassment mean? Do they affect how consultants interact with each other and/or with clients? What kind of environment do we want to build, and how do we get there?

Next, we collected whatever resources we could find on sexual harassment and similar occurrences in writing centers. While the scholarship on the subject was relatively limited, a handful of studies aided us in our journey. Harry Denny’s foundational work, Facing the Center, situates sex and gender dynamics in the writing center as a pivotal point of study. He writes that “our sex, our gender, and the politics attendant to them are ubiquitous in writing centers and to the people that circulate through them” (p. 87). To ignore the different power dynamics, privileges, and potentials for harm that accompany sex, gender, and its intersections across multiple identities is to ignore a key component of the work being done in a writing center space. Denny reminds us that though we cannot fight every battle, we must find strategic moments to fight the gender and sex oppressions we see in our centers (p. 111). This sentiment reinforces the importance of the work we are attempting to accomplish.

Dixon and Robinson (2019), and Nadler (2019) pushed us to question the space of a writing center itself – we want our spaces to be welcoming, but what does that mean? And at what cost? Nader (2019) discusses online writing center spaces and what kinds of behaviors and attitudes are welcome there. Specifically, he addresses tutor consent– by entering online space what exactly are tutors consenting to? Is this consent clearly defined (typically, the answer is “no”)? Similarly, Dixon and Robinson (2019) tackle what “welcome” means inside an in-person writing center, especially when institutional positionality is considered. The university places rules and regulations on a writing center that directly impact what shape “welcome” takes and who exactly is welcome. They call us to redefine comfort, space, ideology, and practice in order to consider what “welcome” means in practice. This is a call we took seriously as we strived to address the incidents in our writing center because we did not want our space to welcome harm.

As Dixon and Robinson (2019) express, writing centers are situated in the midst of institutions that, more often that not, have conflicting agendas concerning the handling of sexual harassment. This is an area that writing centers need to tread carefully, balancing institutional responsibility with the well-being of the students who inhabit the space. Prebel (2015) writes of the implicit harm in mandatory reporting. She argues that mandatory reporting in centers, and across the institution, in reality victimize those who have experienced sexual harassment. Meadows (2021) builds on this work, highlighting key ideas that she believes will spark conversations in writing centers and move us toward finding a solution to sexual harassment that does not leave victims isolated and defeated. She asserts that we must start these conversations with each other and push for some sort of institutional reform – two things we look to accomplish through our work here.

Policy and Power

Using Prebel (2015) and Meadows (2021) as a springboard, it seemed clear that we needed to tackle the problem of institutional policies versus internal, departmental policies. We had no internal policy in place to deal with sexual harassment or other forms of student misconduct at the time these incidents began to occur. In our center, we try to have as few hard-lined policies as possible because we believe that policies, no matter how good-intentioned, typically tend to fail to serve the entire population which they are intended to regulate and can easily become tools of oppression. Our greatest desire is for both our consultants and our student-clients to have agency in the sessions, and we find that the best way to ensure that is to lessen the authoritarian policies in place. We adopted this mentality from the work of Natarajan, Cardona, and Yang (2022), who write about the policies on writing center landing pages from an anti-racist lens. They argue that policies even as simple as “no proofreading” or appointment allotments can send subtle yet clear signals as to who is welcome or not welcome in a space. Sometimes, policies are created with implicitly biased rationales. While many policies seem neutral when taken for face-value, underneath they expose roots in racism and ableism, disproportionately affecting already marginalized student writers and tutors.

To combat this potential marginalization, Natarajan et. al (2022) suggest focusing on the students themselves and how policies affect them, rather than focusing on the nitty gritty of the actual policy. They delineate the distinction by focusing on the who rather than the what:

Getting away from the “what” of policies (What is the permitted number of appointments per writer per week? What training will help tutors address grammar concerns pedagogically rather than editorially?) and focusing on the “who” (Who is making this appointment policy, and to whom does it apply?) may pose perhaps the most significant challenge to policy commonplaces. Writing center policies reflecting accompliceship (Green, 2016) cannot be created top-down.

We wanted to adopt their ideology of people-focused versus policy-focused procedures in our space. While policies do help standardized practices so that every student at the writing center, both writer and tutor, has the same foundation, these policies can also affect the students in different ways. This is something that writing center administrators must be aware of while working with students and when creating the policies meant to protect them. We took this thinking to heart in our writing center, wanting to respect the diversity of our space by keeping rigid procedures to a minimum. We intended our space to allow allow creative expression and autonomy for both writers and tutors to set the boundaries of their consultations. Yet, in doing so, we found that when things get dicey in a session for a consultant, especially concerning sexual harassment, the lack of clear, available policy works toward our disadvantage.

Until these incidents, we had almost been scared of power and authority as concepts; it was now our chance to remedy this stance and find a healthy balance between power and autonomy. In writing centers and related scholarship, there is more often than not an acute need to move away from any sort of hierarchy to ensure that work can be done. We know and live by the mantra “produce better writers, not better papers,” focusing on equipping writers with transferable writing skills rather than making sure they have an A+ paper ready to go by the end of a session (North 1984, 438). Similarly, we strive for our centers to be welcoming homes and not stuffy classrooms or remedial-only spaces. Carino (2003) reminds us that peership is elevated in writing center scholarship as the ultimate form of tutoring, a practice we actively promote in our own center. It represents “writing centers as the nonhierarchical and nonthreatening collaborative environments most aspire to be” (Carino, 2003, p. 96). We see consultants and their clients as two equals, two students, two friends. But should friendship truly be the goal of writing consultations?

Of course, considering friendship is helpful for many consultations, especially when the clients come into their sessions eager and ready to dive into their writing. But more often than not, it can create an awkward dynamic between tutor and writer. Students do not always come into our writing center with the intention to learn and do so happily; many times, students come into our space with the intention of getting extra credit, having someone to write their papers for them, or, in extreme cases, crossing boundaries. If I only see my tutor as a friend, what is keeping me from crossing boundaries and making inappropriate advances? Friendship is a familiar relationship, one that suggests intimacy. Yes, there is inherent intimacy built into the work of consultation as sharing writing is extremely personal and often feels like sharing oneself. Yet, at the end of the day, writing consultation is a job with specific goals. We want clients to feel welcome, safe, and productive while doing their work with a tutor, yet this desire should never come at the cost of our student tutoring staff’s well-being, all for the sake of “friendship.”

There must be some sort of balance between the two extremes of hard-lined policies and idealistic friendship. Tutors need to have agency in their sessions to direct their clients as needed and to add whatever personalization feels right to them, but clear boundaries also need to be established between tutor and client for a safe working relationship to exist. We cannot turn a blind-eye to the power dynamics at play in tutor-client relations for the sake of friendship; this becomes especially important when sessions become difficult. Acknowledging that there is some sort of power dynamic occurring in sessions can help consultants embrace their desired autonomy, not only when shutting down unwanted advances but also in the more predictable difficult sessions, such as when clients are on their phones or clearly have faulty expectations of what writing center consultants can do. Carino (2003) reminds us:

Power and authority are not nice words, but they don’t have to be bad ones, either, when the actions they represent are addressed honestly and responsibly. Writing centers can ill afford to pretend power and authority do not exist, given the important responsibility they have for helping students achieve their own authority as writers in a power laden environment such as the university. (p. 113)

While we do not want to cross the line into an authoritarian regime where administrators dictate exactly what can occur in a session and create rules for every little thing, some level of actual authority given to our consultants and policies in place to help guide sessions truly can be a healthy thing. In order to create policies that brought us closer to this healthy foundation, however, we had to navigate institutional systems and authority, which many times proves to be a much trickier task.

Negotiating Writing Center Ethics and Institutional Responsibility

When it comes to institutional responsibility for a sexual harassment or student misconduct case, the path to accountability and due process can often come with difficulty to alleviate a threatening situation. Institutions are responsible by Title IX to ensure that there is equal access to all University spaces and that such access is not hindered, for example, by another student’s threatening presence. However, institutional responsibility also includes ensuring compliance to reporting, evidence, and investigation standards, some of which have come under scrutiny for taking agency– and consent– away from the victim/survivor.

When writing centers welcome individuals into sessions, they do so with the other person’s consent and right to self-determination, but this culture comes to a halt when mandatory reporting practices bind writing centers to situate the victim/survivor outside of their own autonomy. Holland et al. (2021) write that “lack of consent lies at the heart of both sexual assault and universal mandatory reporting” (p. 3). Regaining this lost sense of autonomy and control is “essential to recovery and healing after individuals experience sexual trauma” (p. 2). However, when an individual– client or consultant– reports to their graduate assistant or directors at the writing center, they may then be subjected to a series of interrogation from one department to another. This may require them to reiterate their stories and endure trauma for the sake of attaining justice, as well as have their consent to privacy be undertaken by university surveillance, the police, attorneys, private investigators, and the perpetrator– all of which came from one nonconsensual report (Know Your Title IX 2021). The ramifications of mandatory reporting become even more pronounced when consultants occupy marginalized racial identities. In these instances, the consequences extend to issues of racialization, mistrust of authority, and the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes.

As with the consultants in our story, the victim/survivor’s racial identity increases their susceptibility to harm from surveillance measures. As Holland (2021) reminds us, mandatory reporting can reinforce the mistrust persons of color already carry as a result of previous racialization, over policing, and personal experiences of police brutality. The fact that “providing safety and support has become synonymous with increasing police presence [and] surveillance” shows what little consideration mandatory reporting policies give to this mistrust (Méndez, 2020, p. 98). In this way, white supremacy becomes enmeshed in mandatory reporting and decreases a student of color’s likelihood of reporting. For Black, Indigenous, and women of color (BIWOC), specific gendered and racialized stereotypes can further inhibit them from reporting out of self preservation. Black women who report face being stereotyped as the “angry black woman” to minimize justified anger over sexual harassment (Morrison 2021). Furthermore, race-specific stereotypes that label Black and Brown women as overly promiscuous can lead institutional authority figures to orient their investigation towards the victim/survivor’s credibility (Buchanan 2002). Surveillance as a result of mandatory reporting then turns into a measure of scrutiny rather than safety for BIWOC victims/survivors.

For writing centers, this dilemma of institutional responsibility and ethics of care is crucial to our commitment to social justice. In her work on mandatory reporting in writing centers, Bethany Meadows (2021) asks, “if we believe students have the right to their own language and voice, then why do we remove survivor agency with mandatory reporting?” If we acclaim students’ self-determination in consultations, then how can we implicate ourselves in processes that remove autonomy, forcibly re-traumatize, and subject survivors/victims to surveillance from institutions that systematically oppress the racial and gendered identities of those who come forward? For writing centers, these dilemmas of institutional responsibility and ethics of care are crucial to our commitment to social justice. Mandatory reporting removes students from a place where they “can experience some distance from institutional authority” to a space where “the center– and consultant– is more in consensus with the institution than in collaboration with the student” (Prebel 2015). In our cases of consultants facing harassment from clients, the balance between institutional cooperation and the culture of collaboration and care we shared for each other became complicated. As Méndez (2021) asks, “to what extent is having Title IX as the only option available to address sexual misconduct one of the preconditions for silencing a diverse range of survivors?” To be able to actualize the work of reducing institutional harm, writing centers must build “viable responses and healing options for the range of survivors who have been deemed systemically disposable” (Méndez 2021). At our writing center, we created our own code of conduct to give our consultants the option to resolve peer harassment without creating unwarranted surveillance or pressure on a student. Doing so, we hoped to enact an ethics of care for our consultants alongside the ethics of care we pursue for student-clients.

Writing Crimes

Throughout the commentary on the newest revisions to Title IX regulations, there is much debate over the requirement that indirect disclosures, such as through an assignment, must be reported. Under these guidelines, “nearly all employees will be required to report when: they have information about conduct that could reasonably be understood to constitute sexual harassment and assault because they… learned about it ‘by any other means,’ including indirectly learning of conduct via flyers, posts on social media or online platforms, assignments, and class-based discussions” (Holland, n.d., p. 186). According to Prebel (2015), “disclosures of sexual assault made in student essays and reflective pieces like personal statements are considered reportable” and under these circumstances, “the mandate to report can thus be interpreted as a form of textual interventionism, a limit on how individual writers might ‘own’ their texts or develop agency through their writing” (p. 4-5). While Prebel references a client’s disclosure about being a victim/survivor, you will remember from Lauren’s story that our writing center was faced with a client’s fictional first-person narrative, whereas the narrator perpetrated sexual violence and murder, including rape, necrophilia, and cannibalism in a dorm setting. The client’s consultant, feeling physical and mental discomfort, removed herself from the session and a graduate assistant explained to the client that he would not be allowed to bring in writing that was harmful to the consultant’s psychological being. The student-writer lodged a counter complaint that they were denied their right to write about and seek consultancy on any subject matter. This is not a debate distant from writing center scholarship as many have reported the complications arising from “questions about whose it is to adopt or accommodate to whom and to what effect” when it comes to working with a client whose writing threatens respect and dignity for the existence of one or many fundamental identities of the consultant (Denny 2010). However, the social injustices that emerge from a passive or indifferent response to these works create a culture that de-prioritizes the consent and inclusivity of consultants and even other clients.

The crux of the issue lies in how a writing center approaches inclusivity. As Dixon and Robinson (2019) write, “inclusivity becomes complicated when writing centers have clients who visit the center with racist, sexist, homophobic, ableist, or otherwise oppressive papers.” Arguments to maximize inclusivity of these clients and their ideas often root in taking a writing-based approach that perhaps challenges sources and evidence, but not ethics. While this more objective angle does enhance the comfortability of the client, it does not serve social justice and through performance, indicates an indifference to the personhood of consultants or clients who share the identities being oppressed. Critical to this proposition is the radical social justice praxis set forth by Greenfield (2019) who addresses the issue of allowing writing consultants to help authors “be more effective in communicating their racism or misogyny” (p. 4). Considering the writing center’s positionality within the larger institution, “our privileging of writers over righteousness risks in both small and large ways our field’s complicity in enabling or even promoting systems of injustice many of us personally reject” (Greenfield, 2019, p. 5). When “the work of writing centers is implicated in these various systems of oppression,” then “we have an ethical responsibility to intervene purposefully” (Greenfield, 2019, p. 6). Others may argue that textual or even verbal intervention in violent writing contradicts the core writing center value of championing a client’s language and voice, but then one must also ask, whose voice and what message is upheld in that apathy? Moreover, where is the consultant’s consent to hear and handle writing directly opposing their existence?

While consultations often defer control to student-clients in order to practice student-centered approaches, it does not mean that consultants also drop their subjectivity. The process of recognition and response is alive on both ends, and both clients and consultants work to balance the inherent power dynamics in their relationship. However, when a client presumes entitlement to a consultant’s right to self-determine their boundaries in a session, including a consultant’s right to remove themselves from a space where their existence or autonomy no longer felt welcome, power is wielded to enact control and oppression. An ethics of care for clients grounds much of our considerations on what “comfortable” and “welcome” mean for a given space. However, it is time that an ethics of care for consultants is also closely considered. It is in that deeper examination that we found the larger implications of student misconduct on our space. Primarily, student misconduct reveals gendered assumptions of consultant work and a client’s rights to the consultant’s mobility, time, intellectual resources, and emotional faculty.

Race Consciousness in Sexual Harassment

Writing center staff is typically female-dominated, perpetuating the stereotype of women as helpers. The notion that women should exist in remedial spaces and provide help to the men that need it and/or desire it, though the men (more often than not) are reluctant to accept such help, is a persistent problem. Denny (2010) writes of this issue:

[Writing centers] strive to be safe spaces or contact zones where facial difference is generally celebrated. More often than not, these inclusive domains have disproportionate representation of women, as tutors or clients, a reality that confirms stereotypes of men’s reluctance to seek help (and women’s comfort doing it). This gendering of support and peer mentoring becomes all the more intense when a space doubly signifies as remedial, somewhere a person who is deficient goes. I’m not saying that in reality, women are any less reticent about deficiency or getting “fixed;” there’s just more of a perceived social stigma that goes along with men seeking help, as if reaching out diminishes our masculinity. (p. 100)

Thus, how we interact with gender in a healthy manner is of utmost importance for the safety of all students that inhabit our spaces, consultants and clients alike. Denny (2010) writes that “our gender and sex are among those political and historical variables that cut through the scene of tutoring. For some, the point of entrée into this conversation vis-à-àvis writing centers revolves around gendered notions of writing—that there are uniquely male, female, feminine or masculine ways of doing and learning it” (p. 89). Gendering in writing centers cannot be escaped– gender is such an outward-facing expression of our innate identities that it is difficult to hide or ignore, even if we wanted to. Similarly, as Morrison (2021) points out, consultants do not leave their race at the door of writing centers, and “racism itself is not dropped at the door of the writing center by anyone” either (p. 120). In and out of the writing center, “experiences of women of color are frequently the product of intersecting patterns of racism and sexism” (Crenshaw, 1991, p. 1243). At these intersections, the dual axis of marginality imposes extra layers of emotional taxation in addition to being stereotyped as nurturing “helpers.”

For women of color, their racial identity presents an additional axis that increases the emotional labor placed on them. BIWOC consultants are placed “in a position of constant negotiation” of identity politics, having to perform what Morrison (2021) calls a “balancing act” of filtering responses to racialized hostility to maintain a hospitable work environment, especially if it’s lacking a conscious commitment to anti-racism practices (p. 124). The lack of a conscious commitment to anti-racism practices amplifies the challenges that women consultants of color face, perpetuating an environment where racialized sexual harassment can thrive. For example, while some instances of racialized sexual harassment may be more overt, such as “hey, you’re pretty for a brown girl,” other instances may be more covert, making it harder to validate feelings of racial targeting within sexual harassment. Such experiences “can be incredibly direct and personal for those who live them, while those who perpetrate the acts may deny them or fail to notice them and their exclusionary effect” (Morrison, 2021, p. 128). In the case of Lauren’s client, implying that access to Lauren was “paid for” by his tuition may have been just one final attempt to pre-approve his harassment; but for Lauren, these comments may invoke a scary reminder of the present manifestations of racial capitalism. The sexual harassment here was apparent. However, the racism Lauren felt may go unacknowledged for multiple factors: its covert presentation, the consultant’s need for self-preservation from gaslighting, and the racial consciousness of the writing center at hand. To cultivate an ethics of care for all consultants, it is essential for writing center culture to commit to addressing overt and subtle expressions of systemic racism and the emotional labor they require to overcome.

Student Consumer Culture & The Gendered Service Industry

Because writing center spaces offer a welcoming environment that encourages empathy and collaboration, they can often be misinterpreted as informal environments where anything goes. Regardless of gender, consultants have to engage in various forms of emotional labor as part of their daily work. It follows, then, that women consultants are already doing a great degree of this type of labor before adding in the gender bias that disproportionately affects them. Navigating gender bias itself takes a great degree of emotional labor, a labor that could easily weigh on a consultant long after the session concludes.

This begs the question of what kind of emotional labor is required of students in writing centers, especially of consultants. Mannon (2021) asserts that emotional labor is typically something we simply expect of writing center consultants without training. It is something we believe is central to working in a writing center, yet we treat emotional labor as if it is something consultants should inherently understand and know how to navigate. It is not something trained or taught; rather, it is simply expected. However, when we ignore this type of work as a very real and very valid part of the writing center experience, we create a space “where the work of managing writers’ emotions is invisible, devalued, and disheartening” (Mannon, 2021, p. 145).

Complicating further the consultant’s emotional burden is the neoliberal idea that students at a university are consumers whose needs must be met at any cost. As displayed in the three stories we shared, there is an overarching theme of entitlement– entitlement to the consultant herself, her time, to the writing center space, to have any sort of behavior accepted, etc. Universities do everything in their power to attract high performing (and high-paying) students, promising an array of services in return, ranging from state-of-the-art gyms to trendy residence halls and to, of course, writing center and tutoring services (Mintz, 2021, p. 88). In this kind of framework, the “customer is always right,” which leads consultants in writing centers to consistently navigate what the client expects of them– another emotional juggle that is not taught, and further, should not have to be. This becomes extremely problematic in writing centers where the front-facing consulting service is primarily conducted by women. The underlying notion of client-as-consumer tips the scale of the power dynamics between client and female consultant before the session even begins.

When dealing with the emotional labor and trauma that accompany sexual harassment in sessions, the conjunction of neoliberal ideals and gendered expectations exacerbates the problems faced by our women consultants. By failing to create a space where emotional labor is validated as hard work as well as having limited policies in place that empower consultants in this emotional labor, both consultants and clients suffer. Nadler (2019) affirms this when writing about student consent for both student-consultants and student-clients. What do we consent to? What do we not consent to? How is this communicated? How does this change depending on the space we find ourselves in? He asks, “when consultants lose agency because of undesirable circumstances they have no choice in entering, how is that not the ultimate form of harassment?” (Nadler, 2019, pt. IV). We centered this question when attempting to find a way forward in our own sexual harassment situation and determined that lacking space for the acknowledgement of emotional labor and the protection of agency in our own center was becoming increasingly problematic. Protecting the consultant’s agency and giving them a clear route to achieve this became our top priority.

Searching for a way forward proved difficult as we wanted to strike an appropriate balance between policy and agency. Denny (2010) raises the question of gender and sexuality in the writing center, asking, “whose burden it is to adapt or accommodate to whom and to what effect. Like the dynamics around sexuality, these moments of gender conflict are fraught with policy and political complications” (p. 93). How do we protect consultants? How do we have clear policies while steering clear of total authoritarian attitudes? We found a solid foundation in the work of Kovalik et al. (2021). Their work in community contracts for online spaces gave us a foundation for our own solution and ushered in a new way to handle policy in writing center spaces. Given the problem of emotional labor Mannon (2021) makes clear, the weight of responsibility writing tutors have when sessions go awry is clearly problematic, especially considering power structures, different identities, and different uses of language. The issue of harassment and misconduct in a writing center muddies the waters for tutors and can cause harm in a space that is supposed to be open and safe (Kovalic et al., 2021). Additionally, because students are typically not trained to handle misconduct (and we must ask – should they be? Is this their responsibility? In their pay grade?), the responsibility falls solely on the tutor experiencing the problem, isolating them and asking them to negotiate in the moment far more than a session agenda. Many tutors shrug “off their uncomfortable interactions, thinking they would never come into contact with the student again– so why bother?” (Kovalik et al., 2021, p. 2). Their idea to combat these inequitable dynamics was to create a community contract, specifically for their online sessions, to take the full responsibility off of their tutors and to share the responsibility equally across the tutor-client relationship. The contract stated what a session is, what its purpose is, what will happen in the session, and what is not to happen in a session. Everyone must sign the contract, ensuring that everyone understands what is expected. This study by Kovalik et al. (2021) became the bedrock of our own– it revealed to us an equitable way forward and promised a bright solution to the problem that had been darkening our center.

Creating the Contract

Contracts and Collaboration

In brainstorming sessions with upper administration, there were questions about what this contract posed theoretically for the power dynamics within writing center culture. Contracts, in a broad sense, are prescriptive agreements between two parties, a set of rules and regulations to abide by that are designed to protect individuals by limiting interpretation and scope. Given that writing center practice prioritizes anti-hierarchical and student-centered approaches to collaboration, contracts in the space can seem too authoritative on the consultant’s end, considering the power they inherently bring to the session. However, according to the collaborative theory of contracts (Markovits 2004), a shared sense of intention and obligations actually sustains cooperation and collaboration better than otherwise. Framed as a legal theory in this context, Markovits’ theory the sustainability of collaboration and community through contracts or promises holds profound implications for how writing centers can reassess the importance of establishing healthy, clear, and secure boundaries. This reconsideration can enhance the comfort of both clients and consultants, fostering a collaborative environment where they can work towards a common end-goal without apprehension of inappropriate motives.

Having a community-contract certainly changes the relations among the clients and consultants who engage in them, but these changes can enhance opportunities for collaboration despite their formality. Markovits (2004) writes that promises “increas[e] the reliability of social coordination and promot[es] the efficient allocation of resources” (p. 1419). This is because promises “establish a relation of recognition and respect– and indeed a kind of community– among those who participate in them” (Markovits 2004, p. 1420). Recognition and respect are the feedback loop which defines the bond between a consultant and a client. As Trachsel (1995) writes, “the intersubjective dynamic of recognition and response, the relational self in close connection with another self, is crucial to the successful enactment of a learning process centered around the student” (p. 38). Even more so, staying honest to a promise or contract “enable[s] persons to cease to be strangers by sharing in the ends of the promises” and fulfillment of their joint intentions (Markovits 2004, p.1447). When clients and consultants can each hold up their end on the promise to conduct themselves with respect for the other’s boundaries and self-determination, they “cease to be strangers and come to treat each other, affirmatively, as ends in themselves, by entering into what I call a collaborative community” (Markovits 2004, p. 1451). Within the nuances of this theory and its application on our own writing center community contract, one can see how what seemed authoritarian actually comes to be integral in sustaining a respectful community.

Brain Dump Doc

With the spirit of collaboration and an ethics of care, our methodology for designing a contract included an all-staff meeting as well as an accessible brain-dump document where all consultants could anonymously pose suggestions for what boundaries would allow them to ensure safety and self-determination in a session. It was easy for us to invite the consultants into these conversations as non-hierarchical collaboration is modeled to us through our own position as graduate assistants, and because their voices are incredibly important to a document that directly affects their experience in their workplace. Consultants were eager to be a part, and were active participants throughout the process. Our writing center staff is committed to one another, as friends and as colleagues, so everyone took the drafting seriously in the hope it would strengthen the already existing bonds in our space. As we can see here, many of our consultants posed their concerns side-by-side in what textually feels like solidarity to protect each other and themselves. The root of many of these issues– such as phone distractions, expecting a consultant to “fix” papers, crossing personal boundaries– rested in the harmful assumption that a consultant’s time and intellectual resources could be disregarded and disrespected. In this document, the staff brought together what they believed defined the contractual obligations or promises of the relationship between consultants and clients from their personal experiences. Most of all, they emphasize a need for shared intention to be present and active with writing to work on in a session. Shared intentions, as per Markovits’ (2004) analysis, is the foundation to coordination. For example, one of our consultant’s suggestions, “must have intention to work on their own writing” better allows for both client and consultant to move forward with the session. When one party does not share this intention, then the consultation moves backwards in progress.

Drafting the Contract

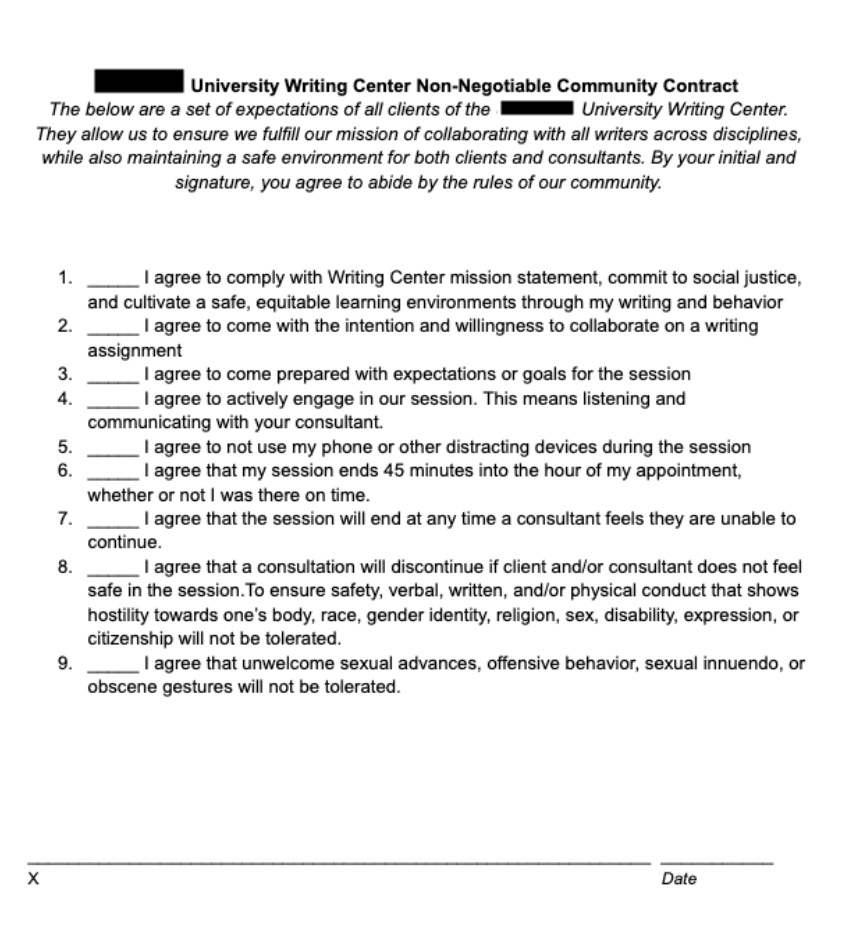

These statements relate to our mission, to the expectations of a client so that a consultation can be collaborative, and to the non-negotiable behavior in a workplace. We wrote this first draft of the contract towards the end of the semester, when student misconduct and sexual harassment reports had lessened, but we still felt its impact across the space. Examining the language here, such as posing every statement with “I agree” and requiring initials, one can interpret how we feared losing the safety of the writing center space, alerting us of a need to be stricter with policy writing and interpretation. To the process of initialing and signing, we also added that these were “non-negotiable” rules for a client to “abide by.” While the language here emerges from the anxiety and need to protect interpretation so that another client could not bend our policies to justify their inappropriate behavior, it nonetheless exacerbated power dynamics in client-consultant relationships. It was focused on giving the power to dictate rules and control interpretation to the hands of writing center staff, rather than welcoming collaboration from our community– something we would later revisit and revise.

Writing this draft, there was much concern about how certain terms would be interpreted and how we could best enforce a culture of accountability that served social justice. One critical method we implemented here was writing what would be considered a breach of this contract. As Markovits (2004) theorizes, “contracts enable persons who are not intimates nevertheless to cease to be strangers; and breaches do not just reinstate the persons’ prior status as strangers but instead leave them actively estranged” (p. 1463). This means that a contractual relationship allows for community building (rather than remaining strangers post-consultation) when recognition and respect of intentions, goals, and obligations are met. However, when they are breached, the contract itself contains the codified authority that allows for a clear discontinuation of that relationship. Because we did not have a clear policy on student misconduct and what breached appropriate behavior in our writing center, clients often felt not only entitled to returning to the writing center but also entitled to working with the same consultant that they had harassed. By having a written document that clearly defined what constituted a breach of appropriate behavior and the consequences for such, consultants and clients could easily point to their right to remove themselves from a consultation and disengage in any unwanted future relationship.

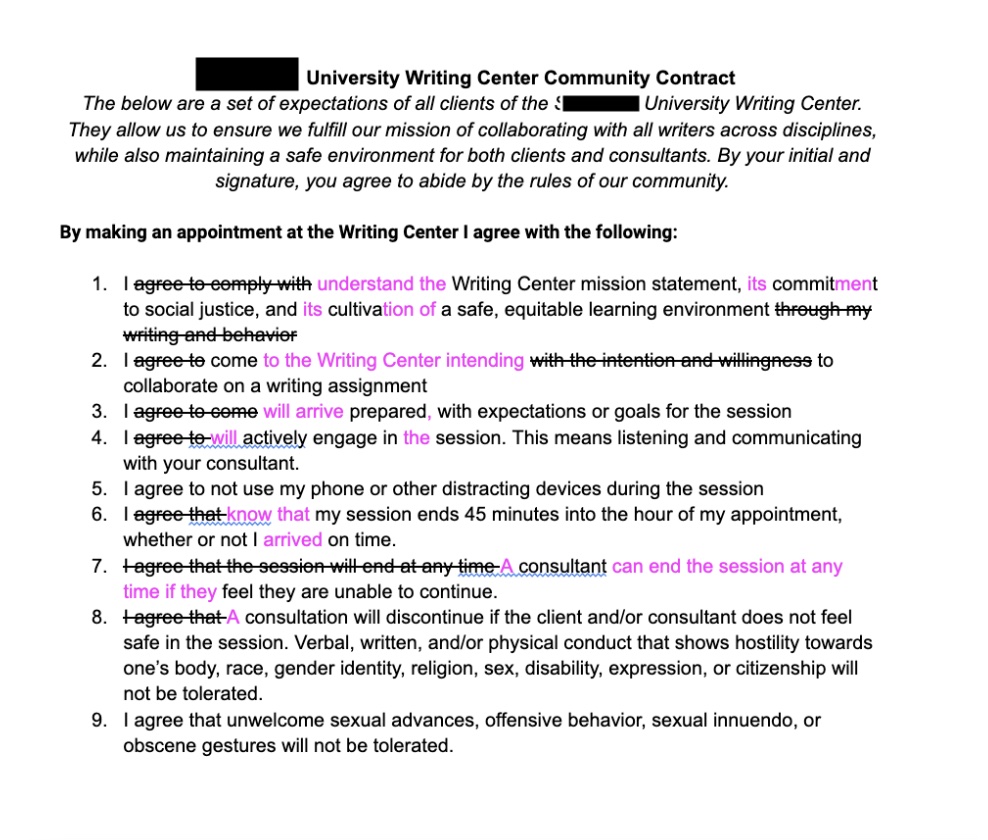

After we had returned from break, graduate assistants and upper administration sat down with our previous draft of the contract. Significant changes were made as we had returned to the community contract with our mission to practice care, collaboration, and non-hierarchical praxis in mind. We removed the initials and replaced “I agree” statements with language to indicate these terms as expectations rather than rules. Removing initials and signatures came from our desire to emphasize that this is a shared community document and to maintain a horizontal relationship with our clients and each other, rather than the traditional vertical hierarchy of promisee and promisor often found in more traditional contracts. By doing so, we also hoped to reiterate these guidelines as part and parcel of community-building in the writing center. We removed the term “non-negotiable” from the title as we began to realize that “writing centers become arenas where the support they provide and the cultural assumptions that go along with them present unfamiliar points of contact between people who might not otherwise be thrown together” (Denny 2010, p.100). As Denny questions in his article, we too considered how we might ensure the safety of our staff while still maintaining spaces that “embrace a diversity of bodies, identities, and practices?” To this point, we altered the language of this contract to match our embrace of restorative rather than punitive approaches toward clients who commit misconduct while still upholding the consultant’s autonomy and feelings as valid and deserving of a righteous response.

Implementing the Contract

Our final community contract and its terms represent a culmination of emotions, thought, scholarship, and advocacy we all experienced in the previous year. Outside of structuring the contract in a more welcoming and supportive tone, we also hoped that our specific terms would assist us in facing interpersonal as well as larger institutional issues we encountered. Our first item establishes our intentions and goals as consultants by pointing clients towards our mission statement. Items two and three as well as term five continue on the mission of creating available and clearly stated expectations to be shared between consultants and clients for greater cooperation. Item four is designed to lower instances where a consultant feels overburdened in the emotional labor they provide to a session. As Mannon (2021) writes, “affective engagements are central to writing center practice” (p.144). By asking clients to come to a consultation when they are ready to be actively engaged and indicating exactly what that labor of engagement involves, clients can hopefully better imagine this often-invisible emotional laboring on the client and consultant’s part. For consultants, “emotional labor might take less of a toll in environments that define it, value it, and establish conditions where it resonates positively” (Mannon 2021, p.161). Mindful of this, term seven also seeks to validate a consultant’s autonomy by authorizing their feelings as sufficient enough reason to end a consultation.

Items six, seven, and eight are designed to protect consultants and clients psychologically and physically. Specifically, in term eight, we sought to clearly answer what Dixon (2019) asks writing centers to contemplate: “We perpetuate the idea of comfort to foster a setting for vulnerability, yet how do we know what is comfortable, what welcome means, for everyone who comes into our space? Who do we prioritize welcome for and how?” In term eight, we assert consultations as spaces with professional boundaries despite being peer-to-peer relationships. In both of these terms, we also hoped to “intervene purposefully” (Greenfield 2019) in the institutional taking of survivor/victim consent through mandatory reporting. By asserting the right of clients and consultants to end a session without having to report to others, we hope this contract can provide one template by which writing centers can “expand anonymous and voluntary reporting options that survivors can control” (Holland 2021, p.3).

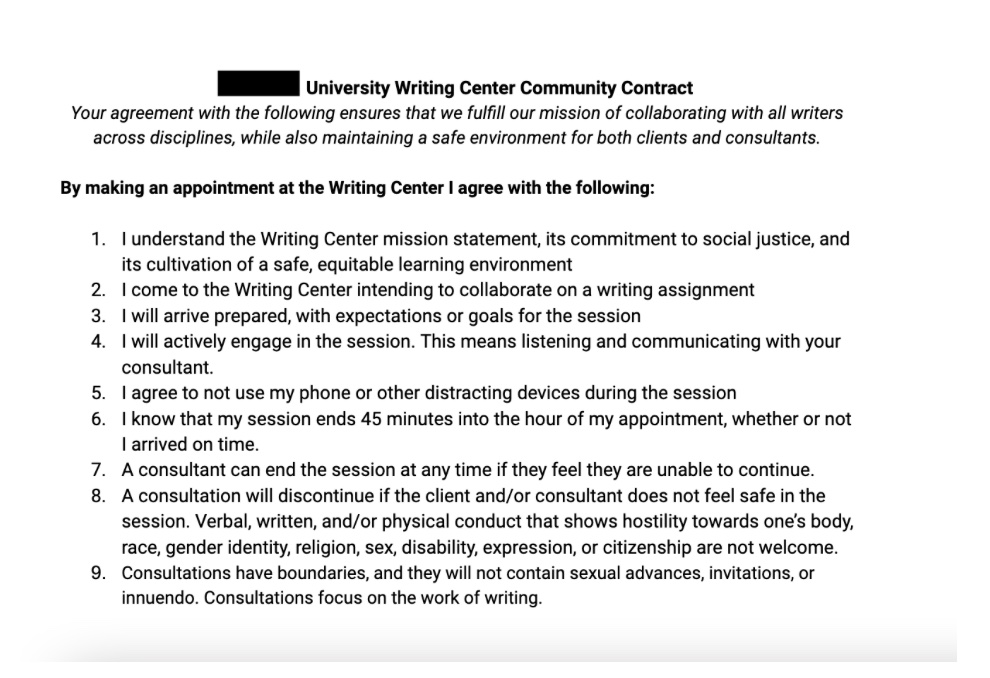

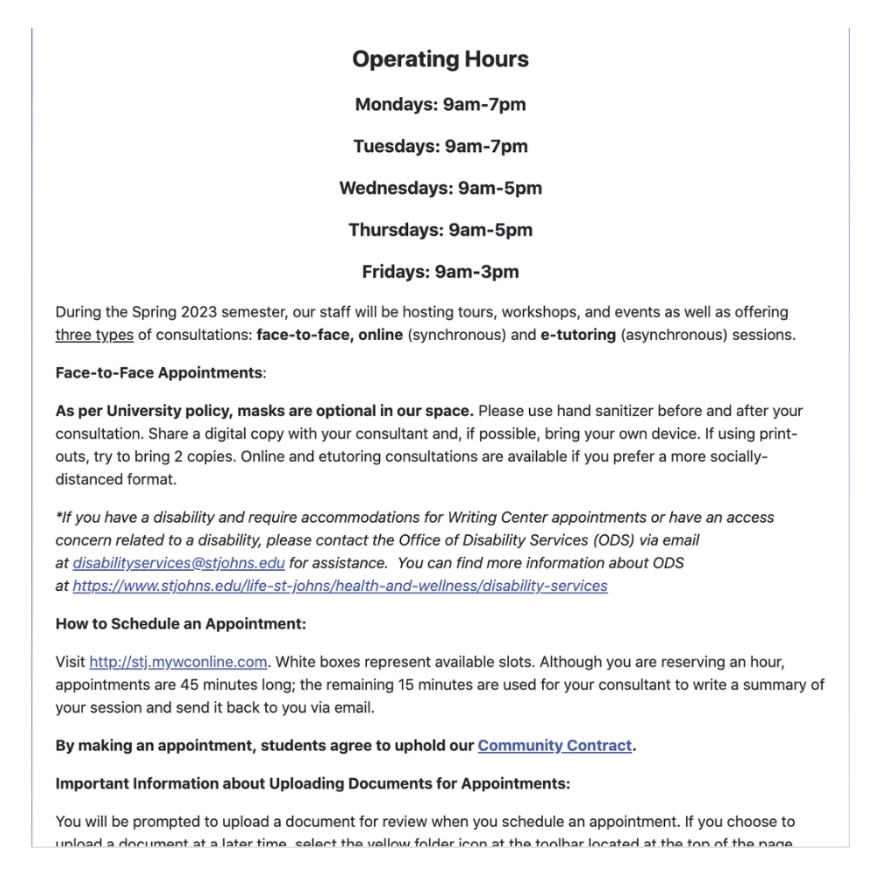

Following our student-centered model, this contract as a whole provided our writing center the status of a community with a heightened sense of empowerment and choice. Rather than enforcing the hierarchical practice of signing the contract, which demands a client’s acknowledgment toward the higher power of the staff’s voice against theirs, we decided to place the contract at the bottom of our homepage for clients to view and know before entering a session (see figure 4). While the client still retains the responsibility of knowing the terms of the contract, we do not necessarily present the contract in a way that might fashion hostility before the consultation even begins.

At its end result, this contract shows how collaboration works best when boundaries are clearly drawn, rather than ambiguously assumed. This becomes increasingly important as the writing center at our university is a female-majority space where consultants’ identities are publicly visible via our scheduling platform. With high rates of sexual harassment on campuses, a female-majority space requires distinct protections necessary for collaboration to flourish. While there is a concern that boundary setting will enforce too much formality, thereby prohibiting consultants and/or clients from feeling comfortable in their sessions, it is important to note that these boundaries in actuality enhance the comfortability of both clients and consultants to work without fear of losing their agency or of tolerating inappropriate behavior (Carino 2003). With the contract in place, consultants and clients enter sessions with clear expectations of what comprises successful sessions, and they have a written and agreed upon exit strategy should a session go awry for any reason.

Looking Forward

It is our deepest desire that the steps that we took at our writing center will bring a tangible lasting change. As both of us are moving on from that university, our involvement in the day-to-day interactions with consultants will be at a minimum, so we lose a little of our ability to monitor the contract’s success. However, we left ways for the future graduate assistants in the space, as well as other administrators and consultants themselves, to keep track of the safety of our consultants. We employed, like Kovalik et al. (2021), a behavior log to keep track of student misconduct and the circumstances surrounding it. This will help our writing center keep track of incidents and potentially be able to predict them before they occur if we see patterns form. We will do this through the center’s scheduling platform, WCOnline. Typically, consultants create client report forms to send to the client as a recap of the session, but they can also be internal reports for the center itself. If there is any problem, discomfort, or misconduct in a session, we can make a report that stays in our system. This will be useful for any future research that will be done in the space and will be helpful for us as we monitor the appropriateness of sessions.

Additionally, we suggest that the future graduate assistants do regular well-being checks with the staff at staff meetings, to see how things are going from their perspective, as well as work to educate new staff on the contract. Because we are a staff completely composed of students, there is much turnover, a problem any academic knows too well. While the student staff that helped create the contract knows the contract well and understands its importance, it is imperative to continually educate future hires of the contract as well, so that it does not lose its credibility or its place in our center. In the same vein, it is our hope that this contract will be a living document, constantly evolving to suit the needs of the writing center population. As new staff comes in and learns of the importance of these policies, we invite new conversations to be had and new iterations of the contract to be created. This is not a project to be sealed shut and packed away– active contributions will keep it alive and ensure that the spirit of the project remains.

We share this process in the hopes that other writing centers across universities will be able to adopt and transform this framework in ways that accommodate their unique spaces and students. We also share the process with the keen desire that we see more scholarship addressing these issues as our work is in no way comprehensive. There is an array of different writing center environments and factors that could change the scope of this work and must be considered. We pose a few lingering questions for future researchers: what happens when misconduct occurs in a center that has evening hours when no administrators are around? What happens when the sexual harassment or misconduct occurs between members of the staff, rather than between a staff member and a client? Even more severe, how do we come alongside students that may feel harassed by their own administrators, beyond whatever institutional measures are already in place? And, lastly, while this work accounts for the sexual harassment of women, especially BIPOC women, how might we consider the other communities that may be at risk of this type of harassment, namely the LGBTQIA+ community?

We also want to encourage the administrators who deal with student misconduct in their centers to remember that they are not alone. Because of our deep level of care for our center and for the students we interact with everyday, we experienced extreme fatigue while working towards a solution. We often speak of protecting the emotional labor of the writing consultants, but confronting and mitigating these incidents requires emotional labor on the part of the administrators as well. Unfortunately, as administrators, there is sometimes no higher authority who can offer the validation of having your needs and labor recognized. This further adds to the emotional labor taken upon by administrators. We experienced this in real-time, and we want to acknowledge how painful it is to juggle institutional expectations and personal commitments. It can sometimes feel fruitless, especially when the atmosphere of your space has changed, and you work desperately to get it back. It is hard but meaningful work. If you are feeling these things, give yourself some grace. Know that the work is worthwhile.

All in all, we believe that the community contract is a helpful tool to writing centers to make concrete policy that protects student workers and student clients alike, all the while maintaining the collaborative, non-hierarchical feel that most centers desire to achieve. We are incredibly grateful to have been able to work with each other and with the undergraduate staff at the writing center to develop this community contract. After seeing the toll that these numerous accounts of student misconduct had on our undergraduate consultants, it feels good to know that we have something in place that will hopefully be able to help. Sexual harassment is an ongoing and under-researched problem in writing centers, something we would like to see change in the near future. We hope that these narratives along with our solution provide inspiration to other centers to begin to tackle the problems of sexual harassment head-on. The work is not over, and it will take all of us, writing center staff and students alike, to change the writing center landscape for the better.

Footnotes

[1] Throughout this paper, all names will be changed, and stories anonymized to protect the identities of our student population

[2] We would like to take a moment here to acknowledge and thank the third graduate assistant in our WC, Chris Ingram, who worked closely with us as a student-leader as these incidents were occurring. He was instrumental in helping us mitigate these issues in real-time, as well as helping us consider alternate strategies of addressing the misconduct, some of which can be found in Appendix B.

[3] Our position is relatively undefined. We exist in a liminal space between the WC’s administrators, the director and assistant director, and the undergraduate staff. We work closely with the center’s assistant director and help him with any administrative tasks (such as scheduling and leading staff meetings) that need to be done. Our primary role, however, is still one of consulting and working with students one-on-one. Approximately 30% of our work is administrative. This makes our position as graduate assistants very fluid; no one day is the same. We often find ourselves liaisons between the administrators and the staff, simply because we are part of both “worlds.”

References

Buchanan, N. T. P. D., & Ormerod, A. J. P. D. (2002). Racialized Sexual Harassment in the Lives of African American women. Women & Therapy, 25(3-4), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v25n03_08

Carino, P. (2003). Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring. In M. A. Pemberton & J. Kinkead (Eds.), The Center Will Hold: Critical Perspectives on Writing Center Scholarship (pp. 96–113). University Press of Colorado.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing Sex and Gender in the Writing Center. In Facing the Center (pp. 87–112). University Press of Colorado.

Dixon, E. (2017). Uncomfortably queer: Everyday moments in the writing center. The Peer Review, 1(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/uncomfortably-queer-everyday-moments-in-the-writing-center/

Dixon, E., & Robinson, R (2019). Welcome for Whom: Introduction to the Special Issue. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/welcome-for-whom-introduction-to-the-special-issue/

Elbow, P. & Belanoff, P. (1999). Sharing and Responding (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Humanities.

Meadows, B., T. (2021). Cracks in the system: Ethics and tensions of mandatory reporting for writing center professionals. The Dangling Modifier. https://sites.psu.edu/thedanglingmodifier/cracks-in-the-system-ethics-and-tensions-of-mandatory-reporting-for-writing-center-professionals/

Greenfield, L. (2019). Introduction: Justice and Peace are Everyone’s Interest: Or, the Case for a New Paradigm. In Radical Writing Center Praxis: A Paradigm for Ethical Political Engagement (pp. 3–28). University Press of Colorado. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg5bszx.4

Holland, K., Hutchison, E., Ahrens, C., Goodman-Williams, R., Howard, R., & Cipriano, A. (n.d.). Academic Alliance for Survivor Choice in Reporting Policies (ASC) Letter on Proposed Title IX Regulations. https://psychology.unl.edu/sashlab/ASC%20Response%20Letter%20to%20Proposed%20Title%20IX%20Mandatory%20Reporting%20Regs.pdf

Holland, K. J., Hutchison, E. Q., Ahrens, C. E., & Torres, M. G. (2021) Reporting is not supporting: Why the principle of mandatory supporting, not mandatory reporting, must guide sexual misconduct policies in higher education. Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, 118(52), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116515118

Know Your Title IX. (2021). The Cost of Reporting: Perpetrator Retaliation, Institutional Betrayal, and Student Survivor Pushout. Retrieved from https://www.knowyourix.org/wp- content/uploads/2021/03/Know-Your-IX-2021-Report-Final-Copy.pdf

Kovalik, J., Haley, M., & DuBois, M. (2021). Confront student misconduct at the writing center. The Dangling Modifier, 27.

Mannon, B. (2021). Centering the emotional labor of writing tutors. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 143–168.

Markovits, D. (2004). Contract and collaboration. The Yale Law Journal, 113, 1419–1514. https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/224_ah6tbit6.pdf

Méndez, X. (2020). Beyond nassar: a transformative justice and decolonial feminist approach to campus sexual assault. Frontiers, 41(2), 82–104.

Mintz, B. (2021), Neoliberalism and the crisis in higher education: The cost of ideology. Am. J. Econ. Sociol., 80: 79-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12370

Morrison, T. H. (2021). A Balancing Act: Black Women Experiencing and Negotiating Racial Tension in the Center. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 119–142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27172216

Nadler, R. (2021). Sexual Harassment, Dirty Underwear, and Coffee Bar Hipsters: Welcome to the Virtual Writing Center. The Peer Review, 3(1).

Natarajan, S., Galeano, V., Cardona, J. B., & Yang, T. (2022). What’s on Our Landing Page? Writing Center Policy Commonplaces and Antiracist Critique. The Peer Review, 7(1).

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433.

Prebel, J. (2015). Confessions in the writing center: Constructionist approaches in the era of mandatory reporting. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 40(3–4), 2–8. https://wlnjournal.org/archives/v40/40.3-4.pdf

Suhr-Sytsma, M., & Brown, S.-E. (2011). Theory in/to practice: addressing the everyday language of oppression in the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 31(2), 13–49.

Trachsel, M. (1995). Nurturant ethics and academic ideals: Convergence in the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 16(1), 24-45. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43441986

Appendix A: Title IX

On Title IX’s 50th anniversary in 2022, the U.S. Department of Education under the Biden-Harris administration proposed new amendments which sought to revise new regulations imposed under the previous Trump administration in 2020. The 2022 update to Title IX would broaden the definition of sexual harassment and eliminate the requirement for live cross-examination in grievance procedures (Holland n.d.) but it expanded mandatory reporting measures unfavorable to a victim/survivor’s psychological healing process. Commenting on this very matter, the American Alliance for Survivor Choice (AASC) wrote a letter to the U.S. Department of Education as one of nearly 240,000 comments sent to the department of education on this matter. Namely, the research found by the AASC confirms that mandatory reporting as an institutional requirement runs against the grain of ethics integral to the writing center space.

Writing centers care, welcome, and collaborate with a pedagogy rooted in non-hierarchical, cooperative, and experience-affirmation. In the minds of many writing center personnel, it is a space of liberation and comfort, an oasis to the other departments in a University that come with stricter regulations. However, “a center’s positionality within an institution creates a layered notion of power and hierarchy that can complicate how and to whom ‘welcome’ is made” (Dixon 2019). Holland et al. (2021) write that “lack of consent lies at the heart of both sexual assault and universal mandatory reporting” (p. 3). Regaining this lost sense of autonomy and control is “central to recovery and healing after sexual trauma” (Holland et al. 2021, p. 2)However, mandatory reporting enforces an indifference to the fundamental principles of trauma-informed work– “empowerment, voice, and choice–” (Holland et al. 2021, p. 2) regardless of its weight on a department’s culture or values.

Appendix B: Other Anti-Harassment Strategies

Encouraging Physical Closeness

Beyond the community contract, we also developed different protective and communal practices for the well-being of our consultants, practices that could easily be implemented in other writing centers. The first step we took to ensure the safety and security of our consultants was to have consultants sit together. Our writing center is rather large (larger than many others we have encountered), consisting of 10 long wooden tables and three distinct groups of couches, and is a shared space, meaning that students can come in even if they do not have a writing center appointment. To encourage camaraderie and safety, we now have the first two rows of tables reserved for consultants and consultations only. This security measure enables the leadership of the writing center to have an “insightful” view of our consultants, in that we can both see them to build visibility and comradery and can ensure that the interactions between clients and consultants run smoothly, without any negative exchanges.

Small Mentor Groups

Additionally, we emphasize community to foster well-being in our space. Being in a community is important to us at the writing center; it is where we get to share ideas as well as collaborate with and be there for one another. In our writing center, we have had a long-standing tradition of having what we call “small mentor groups.” Each graduate assistant is paired with 3 – 5 undergraduate consultants who meet bi-weekly to discuss important issues inside and outside the writing center. When experiencing the height of the sexual harassment incidents, we saw the small mentor groups as a therapeutic space to relieve stress for our staff, to discuss the issues of sexual harassment and student misconduct, and to determine how to move forward. Some of the feedback we received from our staff made its way into the community contract, exemplified by the brainstorming document shown in Figure 1.

Special Initiative Groups

Another way we promote community, collaboration, and inclusivity in our writing center is by having “special initiative groups.” Led by graduate assistants or by undergraduate consultants, these groups focus on a specific topic of interest and advance the values of the writing center. Two special initiative groups that students collaborate on at our writing center are the Black Writers Initiative Group and Social Media Initiative Group. Within the Black Writers Initiative Group, consultants who identify as Black collaborate by reading Black authors work, by discussing the issues of race in the writing center and on campus, and by curating events to promote African American History and Culture. This past semester, The Black Writers Initiative group hosted an “Hip-Hop showcase” event to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Hip-Hop. The Social Media Initiative group is open to all consultants who have an interest in the outreach and marketing of the writing center. During meetings, they brainstorm weekly Instagram posts, identify who is doing what within the group, and how to increase follower count and foot traffic on our page. Overall, these groups do the important job of bringing consultants together to foster partnership and promote a safe environment while working to achieve a larger goal. They advance the peer-to-peer support that is crucial when fostering an environment that protects its students.

All-Staff Boundary Workshops

Lastly, we used one of our weekly staff meetings to hold a boundary workshop for our consultants in the spirit of conversation. Taking the format of a roundtable discussion, the administration and consultants worked together to determine where the issues and confusion stemmed from in these types of sessions. We learned that boundary setting proved difficult in some cases, and consultants were not sure how much discomfort they were supposed to be able to handle. We discussed what the job of a consultant is and what it is not, what is our role as emotional guides, should we have that kind of a role at all, etc. We reviewed boundary setting language, such as clarifying a consultant’s exact abilities, referring clients to the counseling center if it was clear that they needed emotional support more so than writing support, and asserting the right to terminate a session. Examples of this kind of language include questions like, “What are your goals for the next 45 minutes?” and clarifying statements like “Let me clarify how a consultation works…” or “This is a professional relationship– please refrain from making inappropriate comments.” These kinds of conversations assured consultants that administrators were on their side and ready to help them and build camaraderie between consultants moving forward. Simple conversations and minor changes can lead to tangible change, as these different strategies show, which is why we hope to encourage it here.