Alexis Stewart, York College of Pennsylvania

Abstract

This study explores the impact of multimodal feedback types on student experiences with asynchronous writing tutoring. Through analysis of survey responses from students who utilized Drop-Off Essay Review appointments at a small, private college, this study finds that the combination of written and video feedback enables students to better understand and engage with asynchronous feedback from their tutors. Findings indicate that most students prefer video feedback or a combination of video and written feedback, noting that the video feedback helps elaborate on the tutor’s written comments. Results also suggest that offering multiple feedback options may help writing centers reach a wider range of students, as participants expressed varying individual preferences for different feedback types. Furthermore, the asynchronous format appears to provide a more comfortable entry point into tutoring for some students. This study contributes to the limited research on multimodal feedback in asynchronous writing tutoring and highlights the importance of examining how combined feedback types impact student experiences.

Keywords: asynchronous tutoring, multimodal feedback, writing centers, student engagement, inclusivity

Asynchronous methods of tutoring, in which tutors and students provide and review feedback on their own schedule, have been increasingly introduced in many college and university writing centers. While asynchronous tutoring is not a new concept, such tutoring methods provide the opportunity for students to receive feedback on their writing without ever needing to meet with a tutor, which brought great value during the online times of Covid-19 and led to these methods becoming more widespread during and after Covid restrictions. Often, asynchronous feedback is received in a written format, though asynchronous tutoring can also utilize audio and video feedback from tutors.

As a new tutor providing asynchronous feedback to students, I often noticed students would not review all forms of feedback provided to them; many would ignore the screencast video provided with their written feedback, and this brought forth the question: were both feedback methods necessary? This study aims to understand how multiple feedback types (written feedback, in which the reviewer uses forms of written communication such as imbedded comments, emails, or letters; audio feedback, in which the reviewer records their voice talking through their feedback; and video feedback, an expansion on audio feedback in which the reviewer provides a video both talking through and showing their feedback) impact student experiences with online writing tutoring when used in combination with one another.

This article will first examine previous research on asynchronous feedback methods, looking at comparisons between asynchronous and in-person feedback, considering the specific pros and cons of asynchronous tutoring, and exploring the impact of written versus media feedback, before presenting data from a study that explores student experiences and perceptions of online, multimodal feedback. Overall, I argue that using multiple feedback types creates a valuable relationship between those methods, allowing students to better understand and address asynchronous feedback from their tutors.

Comparing Face-to-Face and Asynchronous Tutoring Methods

Previous research has compared asynchronous and face-to-face tutoring (where tutors and students meet at the same time to discuss that paper), finding that the online format can change various aspects within tutoring. In Bell’s study on 10 asynchronous sessions, she found that “tutors are not simply applying the tutoring techniques and strategies they use in in-person session in a new online setting, but they are adapting these tools and approaches” (2019). Buck et al.’s study investigating online tutoring comments also notes how an online setting impacts feedback, explaining that the asynchronous format “introduces many interpretations of the tone” which can shift how feedback is received (2021, p. 38).

Separate pieces of research investigating the difference between in-person and online formats also comment on how this difference impacts the tutor-tutee relationship. Buck et al. explain that the “tutor and writer cannot have conversations setting the agenda for the upcoming session,” and that this lack of communication among each leads to a shift in focus between the two, with the tutor and tutee often maintaining different priorities (2021, p. 39). These researchers continue to explain that the lack of contact between the two results in the tutor being unable to adjust their tutoring style in ways that is often done within face-to-face sessions. As tutors are unable to see how students will respond to their feedback, they are unable to get to know their student as a writer in their session, which is often vital to adjusting tutoring feedback based on the writer’s abilities (Buck et al., 2021, p. 39). Bell also explores the tutor-tutee relationships in her research, noting that tutors often made more attempts to define roles between themselves and the student in their sessions in order to “define relationships in an asynchronous setting where participants are not both present to otherwise negotiate and establish roles” (2019).

Bell also found that tutors adapted to the online setting by finding different approaches to keeping attention on the subject at hand. Within face-to-face tutoring, it is common for tutors to read papers aloud in order to stay on the same page as their tutees. Within Bell’s study, she found that asynchronous tutors utilized screencast videos as a visual prompt to draw attention to the section tutors focused on (2019).

Other findings on the shifts between in-person and asynchronous tutoring consist of the format itself. Breuch (2005) explains that the media within face-to-face tutoring remains consistent across sessions, with tutoring always occurring within a physical space and through speaking to one another. In online writing centers, however, there are numerous options to communicate, and communications can take place in a variety of formats such as email or Microsoft Word (p. 23). These differences between the tutoring methods can ultimately impact a student’s experience with writing tutoring.

Asynchronous Pros and Cons

Various literature also demonstrates that many students prefer and value online options for tutoring specifically. A study conducted by Bell and others finds three common variables for why students opt for asynchronous appointments: time, physical space, and feedback. Students feel asynchronous options make “best use of what little time” they have available in their busy schedules, provide a space for those with distance to travel to reach the center or that is more comfortable for those not finding the physical center accommodating for their needs, and provide feedback types that students find favorable (Bell et al., 2021, pp. 6-7). Another study highlighting how many students appreciate online options for tutoring found that 40% of participants from asynchronous appointments said that they would only come for online tutoring, while 57% of in-person respondents said that they would only come for in-person tutoring (Barron et al., 2023). This fact highlights the value placed on each tutoring form by students and shows that despite the changes from in-person to online, both options are valued by different students.

Aside from students’ preference for the option, online tutoring brings many advantages. As mentioned, previous research establishes the benefits of time, change in physical space, and feedback (Bell et al., 2021, pp. 7-6). Chewning (2015) also comments on the benefit of time in online tutoring, elaborating that such methods provide more freedom to students “particularly in terms of when contributions to the process can be made by either party,” allowing for both tutors and tutees to address the appointment when they are ready and able to (p. 59). Gallagher and Maxfield echo this sentiment, explaining that the online format allows for students to “take breaks and work on certain revisions” before revisiting feedback, allowing for students who might get overwhelmed from large portions of comments to review their tutor’s feedback at their own pace (2019).

Another benefit brought from asynchronous tutoring is the permanence of the feedback. Gallagher and Maxfield (2019) explain, while students have to rely on memory and any potential notes taken in face-to-face tutoring to inform them while making revisions after an appointment, students in asynchronous appointments are left with written or multimodal artifacts to reference at any point when working on revisions. They further explain that such an artifact can be utilized by students “to build a personal library of supplemental material over time” (2019). Bell and others also discuss this advantage in their study, explaining that because feedback is given in a more permanent format through comments or videos, students are able to revisit this feedback whenever they desire (2021, p. 7).

Finally, an interesting benefit brought from asynchronous tutoring methods is that such options provide the ability to reach new students, bringing an aspect of inclusivity that may be lacking from in-person opportunities. In a study that incorporated several new tutoring options onto their campus, including an asynchronous option that they refer to as Written Feedback, it was found that “the more traditional in-person modality was the only modality where a majority (54%) of writers identified as white (191 of 356 respondents)” which suggested that while white students opted for “traditional in-person tutoring,” non-white students tended to prefer non-traditional methods of tutoring (Barron et al., 2023). Thus, this study concluded that nontraditional tutoring such as asynchronous tutoring allowed the typical boundaries of the writing center to be stretched in order to reach students who wouldn’t utilize in-person options. A similar finding came in a study investigating why students choose asynchronous options, stating that “those using online tutoring services may do so because in-person writing center programming is not always easy to access and not always designed to be inclusive” (Bell et al., 2021, p. 8). Thus, various research indicates that asynchronous and online tutoring reaches new audiences, often including students within marginalized groups, who might not feel comfortable visiting the physical writing center.

There are also various findings displaying the disadvantages of asynchronous or online tutoring. For instance, Chewning (2015) explains in his findings through implementing online tutoring in his institution that there is value from in-person tutoring that simply cannot be recreated through online tutoring without proper resources which come with financial cost and the need for more staff or training. Due to this need, he states that a hybrid approach where writing centers offer a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous tutoring options, rather than solely replacing face-to-face tutoring with online options, would be more effective for institutions like his that are unable to provide the necessary funding and staffing (p. 61). Breuch (2005) discusses how the frustration people have with online writing centers stems from expecting these online options to function the same as in-person tutoring, but online writing centers need to have their own approach and adapt to the online format in order to be best suited for their format (p. 32).

Chewning (2015) discusses how personal preference also means that some writers or even professors may be more receptive to face-to-face tutoring over online options (p. 59). Other research establishes, however, that there is a lot of preference for online formats. A study conducted by Wolfe and Griffin (2012) found that “87% of student writers who participated in an online session either preferred the online environment or had no environment preference” (p. 81). Satisfaction with feedback was also analyzed, and the study “found no significant differences in our expert raters’ perception of the instructional quality of the sessions; moreover, participants were equally satisfied with the consultations regardless of environment” (p. 83).

Written Versus Video or Audio Feedback

Research on the use of different feedback methods is also crucial to understanding how asynchronous tutoring works. While there has been investigation of the use of video feedback within instructors’ feedback to students for over 10 years, only in recent years have there been writing center-specific research about asynchronous videos. Despite this drawback, findings from outside of the writing center can still inform how writers interact with different feedback types.

Research on written feedback is wide with many interesting results. First, there are various ways that written feedback can be provided. Gallagher and Maxfield (2019) discuss how asynchronous feedback delivers writing in the format of advice letters, which differs from the common practice of utilizing embedded comments in student papers. These researchers explain how this format “still allows the tutor to address very specific passages, just as embedded comments do, by copying and pasting them into the advice and making them an integrated part of a more global discussion,” allowing the written feedback to focus on larger portions of the text more easily than is done when embedding comments, which focus on a specific section of the paper. Another study incorporated a pilot program testing different online tutoring options. In this study, both email and message board tutorials were utilized as written feedback forms, and it was found that message board tutorials were more effective for this institution (Chewning, 2015, pp. 60-61).

As marginal or embedded comments are a more common form of written feedback, however, most research focuses on this type. A study on the effectiveness of online tutoring (ETutoring) comments found that this feedback type results in effective revision from students, explaining that “student revision in response to tutor commentary is typically of a high quality” (Buck et al., 2021, p. 38). A study utilizing Microsoft Word to make marginal comments as a form of written feedback to students in the classroom found that this feedback type tends not to be perceived as conversational by students, even if the instructor makes specific attempts for feedback to be worded conversationally (Silva, 2012).

In discussing audio feedback, many researchers point out the humanity that this feedback type brings to the table. Gallagher and Maxfield (2019) comment that “A student then knows from page one that the work submitted was reviewed by another person, that a human being has invested time and energy in the student’s success.” This sentiment is echoed within studies done in the classroom setting, in which students comment that their instructor’s video feedback “added a more personal touch” and that “it was fun to put a voice with a name” (Cavanaugh & Song, 2014, p. 126).

Research on video feedback specifically, rather than simply audio feedback, finds that “Satisfaction with online asynchronous screencast tutoring was readily visible throughout the data, but the importance of offering other tutoring options was also clear” (Bell et al., 2021, p. 8). In her own study, Bell (2019) also analyzes how screencast videos impacts tutor feedback, explaining that “tutors rarely relied on a single technique or strategy” while creating their video feedback, and that “In addition to providing feedback, tutors appeared to use multiple tutoring strategies and techniques to encourage audience awareness, reflection, and critical thinking, encouraging and engaging writers in the learning process.” Furthermore, in video format, it is found that the combination of visual and auditory feedback provides opportunities for focus on larger concerns while still providing the opportunity to point out specific portions of text (Silva), similarly to how embedded or marginal comments function.

Cavanaugh and Song’s (2014) research also noted some comparisons between the two feedback types. They explain, “Students in the study noted that the instructor’s tone was quite favorable when receiving audio comments. They found this in contrast to the tone communicated in written format” (p. 126). Their research also highlighted another difference between the two feedback types in which the focus of feedback provided shifted depending on the feedback type. Within written feedback, it was found that professors often focused on micro-level issues such as grammar and mechanics, while audio feedback typically focused on macro-level issues such as organization and overall topic of the paper (pp. 126-127). This finding was echoed within Silva’s (2012) research in which she explains that written feedback drew attention to specific sections of the paper such as specific words or sentences, while video feedback “afforded detailed discussion of macro level issues.”

Students further noted that written feedback tended to be more specific, but audio feedback often was more detailed in providing examples (Cavanaugh & Song, 2014, pp. 127-128). In discussion of these findings, the researchers suggest that audio feedback provides a more similar experience to face-to-face instruction, which is echoed by some students’ opinions on how the audio feedback was more engaging in maintaining attention similar to when in the classroom (Cavanaugh & Song, 2014, pp. 128-129). Buck and others (2021) comment on similar findings as it pertains to written feedback, finding that students often utilized written comments from their tutors “to make the most formal revisions, such as changes in spelling, punctuation, and usage” (p. 38). In fact, this study finds that even when tutors do focus on macro-level issues in their written feedback, students “do not respond to those comments most frequently,” and instead opt to focus on micro-level issues (p. 38).

Student preferences for feedback types tended to differ, with these studies by Silva, and Cavanaugh and Song highlighting the importance of both options. Both studies show that students found written feedback to be valuable for the revision process but enjoyed the more personal mode of feedback within the video or audio feedback (Silva, 2012; Cavanaugh & Song, 2014, pp. 127-129). In the case of Silva’s research, the students who participated requested that their professor utilize a “hybrid approach” of the differing feedback types at the end of the study.

While the research above highlights many findings on asynchronous tutoring, this study intends to fill the gap in research on multimodal feedback methods within asynchronous writing tutoring. This study emphasizes the importance of how student experiences may change depending on various feedback types, particularly when one type of feedback is used in combination with another type. While previous research focuses on the impacts of separate feedback types, often not within a tutoring setting, this study investigates how a structure containing multiple feedback methods enables students to engage with their writing feedback in a tutoring setting.

Research Context: Drop-Off Essay Review

At a small, private, comprehensive college in the Mid-Atlantic, Drop-Off Essay Review (Drop-Off) was introduced to the Writing Center in the fall of 2019 to implement asynchronous tutoring alongside in-person and Zoom options. Students are able to sign up their paper, prompt, and rubric through an online submission form for a Drop-Off appointment and receive feedback from a writing tutor by 9 pm the same day as their appointment. Drop-Off utilizes three main forms of feedback: marginal comments left directly on the student’s paper, a cover page attached to the top of the student’s paper, and a screencast video made through Vidgrid provided through a link in the cover page.

Tutors are provided instructions for conducting Drop-Off appointments. Such guidelines include leaving feedback that address higher-order concerns such as organization and local concerns such as grammar and mechanics feedback where appropriate. These guidelines also instruct tutors to utilize their recordings to either summarize or explain the feedback they provide through comments and the cover page summary. Finally, tutor instructions for Drop-Off are to spend up to 60 minutes on each appointment without going over this time limit.

The cover page summary portion of feedback includes various pieces of information for students to review. First, the rubric provides a section for the tutor to greet the student and introduce themself by name. The next section of the cover page provides a link to the video summary or explanation that the tutor created, while the third section is optional for tutors to utilize whenever additional disclaimers are needed. A notable disclaimer is one warning the student that the tutor did not receive the assignment instructions, and, as such, was not able to ensure that the paper met all requirements; however, multiple disclaimers exist for tutors to utilize (Fig. 1).

The rest of the cover page provides the assignment requirements and tells the student which requirements were met, provided that the student attached instructions to their appointment, and gives the three priorities that the tutor focused on when providing feedback. Then, the cover page provides sections for the tutor to point out what the student did well in their paper and what they could change to improve upon their paper. To view the full Drop-Off cover page and its contents, see Appendix A.

Data Collection

This study was conducted through an online survey composed of both open- and close-ended questions. This survey was created through the use of Google Forms which provided the opportunity to divide questions into sections. For the purpose of this survey, questions were divided into three separate sections. The first section covered informed consent and allowed participants to opt in to the survey or to select that they do not consent to participate. The second section covered demographics to give a sense of who was utilizing Drop-Off Essay Review. The third and final section instructed participants to reflect on their most recent drop-off appointment when responding, and aimed to understand student experiences with Drop-Off and the various feedback types. The second and third sections utilized a mix of closed- and open-ended questions, while the informed consent section consisted of one closed-ended question. To view a full list of the survey questions, view Appendix B.

The participant pool for this survey consisted of current students at this institution, who had made a Drop-Off appointment during the current Spring 2023 semester and prior to the survey’s start. As the survey was sent out on March 1st, students must have had a Drop-Off appointment on or before March 1st during the Spring 2023 semester, which started on January 25th. Following these parameters, I was left with a potential participant pool of 50 students.

To reach participants, I drafted a recruitment letter and sent out this email to the fifty students’ official institution emails. This email was sent from the official Writing Center email account rather than using my personal email in order to show students that this survey was an official study through the Writing Center. The email noted that the first 20 respondents to the survey would be eligible to receive a small participation prize, with options varying but all equivalent to $5.

The survey was opened to responses on March 1st, 2023, the same day that the recruitment email was sent to the possible participants. The same recruitment letter was sent again on March 14th from the official Writing Center email to serve as a reminder before the survey would close. This survey was open for responses through March 17th, after which point the survey was closed to further responses.

To analyze responses, open-ended questions were coded for similar themes among each student’s responses.

Results

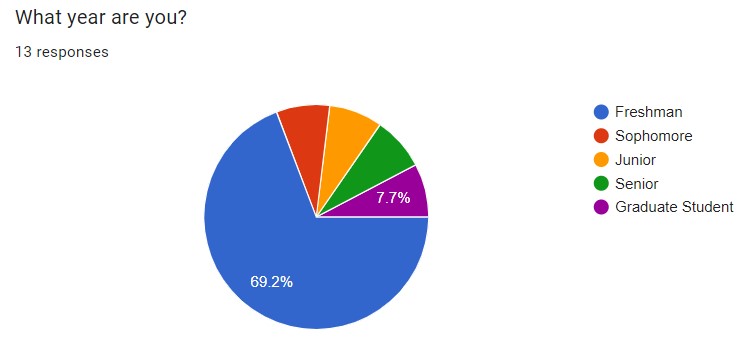

The survey gathered a total of 13 responses which is 26% of the possible participant pool. Out of these participants, nine indicated that they identified as female and four indicated that they identified as male. The majority of these participants were on-campus residents, with 10 out of 13 (76.9%) living on campus and 3 out of 13 (23.1%) commuting to class. Most respondents were freshman, with nine indicating that they were freshman and the remaining four being a sophomore, a junior, a senior, and a graduate student (Fig. 2).

There was hardly any overlap between selected majors between the participants, with only two sharing a major between each other of Nursing. The rest of the students’ majors were Intelligence Analysis, Environmental Science, Undecided, Elementary and Special Education, Finance, Second Education Social Studies, Sports Management, Criminal Justice, Business Administration, Music industry and Recording Technology, and Masters of Business Administration majors.

Most students had experienced Drop-Off prior to the semester in which this study was conducted, with eight students indicating they had a Drop-Off appointment before the Spring of 2023. The same amount of students also indicated that they had experienced in-person or Zoom tutoring in the Writing Center. Around half of the students had used Drop-Off to fulfill a class requirement to visit the Writing Center, with seven indicating they used Drop-Off to fulfill a class requirement.

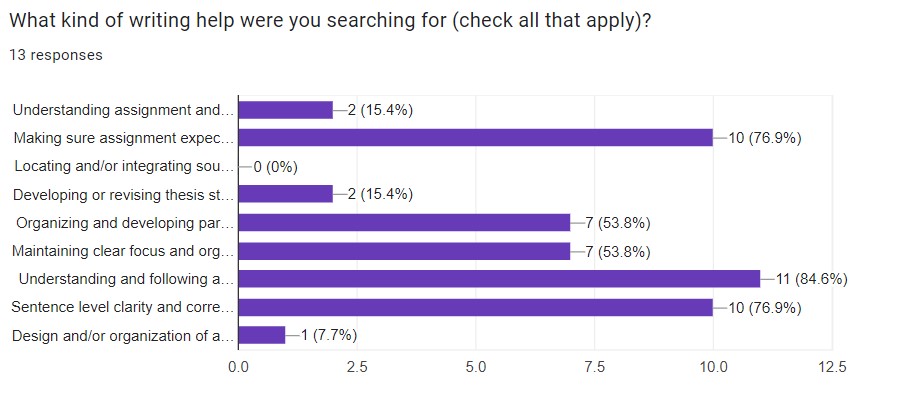

Answers to what stage of the writing process students were in shows that most students used Drop-Off appointments when they had already written a full draft of their assignment. Of the 13 students, 12 submitted full drafts of their papers and four of these drafts already received previous feedback from a peer or instructor. Student responses to what help they were seeking varied, with the most frequent answers being 11 wanting help understanding and following a citation format, 10 wanting tutors to help ensure the student had met all assignment requirements and expectations, and 10 wanting help with sentence level clarity and correctness such as grammar and mechanics (Fig. 3).

Students had a variety of answers for why they selected a Drop-Off appointment instead of Zoom or in-person tutoring. The most frequent answers included the time and convenience, though a select few responses also explained that their situation did not feel necessary for face-to-face tutoring or that Drop-Off was more comfortable than face-to-face tutoring. One respondent skipped this question, so a total of 12 students provided reasoning. Coding student responses, six indicated time as a reason, eight indicated convenience as a reason, three indicated face-to-face did not feel necessary for their situation, and two indicated comfort as their reason. To see examples of each coding response, see Table 1.

Table 1. Coding participant reasons for selecting Drop-Off instead of face-to-face tutoring.

| Response | Coded Reason(s) | Keywords/rationale | |

| Student A | “The asynchronous option was great for me because I could send in my essay, and then revise my edits within my own time! It was a great option because I have a busy schedule with work and classes!” | Time, convenience | own time, busy schedule |

| Student B | “It takes less time to submit my essay and wait for feedback, than to actually take time out of my day to go to an appointment.” | Time | takes less time, take time out of my day to go to an appointment |

| Student C | “I just needed someone to look over it and fix my commas and things in that manner. It doesn’t seem like something that requires me to actually meet with a person.” | Face-to-face not necessary | Doesn’t seem like something that requires me to actually meet with a person |

| Student D | “I had other work I had to work on, and I understand they’re all nice people, however im not a people person, so if the drop-off is an option without any social interaction I will always pick that. I also found that it’s working for me, when I get my essay back from a drop offer I can understand all their recommendations, if I had questions on them I may go in person so I can understand it more, however so far drop off has worked perfectly fine for me.” | Comfort, face-to-face not necessary | not a people person, option without any social interaction, if I had questions on on them I may go in person…so far drop off has worked perfectly fine |

When responding to which forms of feedback each student reviewed, 12 students reviewed the screencast video, nine reviewed the marginal comments, and seven reviewed the cover page summary. Only a total of six students reviewed all three forms of feedback in their appointment. Of the remaining seven students, three indicated that they reviewed the video feedback only, one indicated that they reviewed the marginal comments only, two indicated that they reviewed both the video and marginal comments, and one indicated that they reviewed both the cover page summary and video.

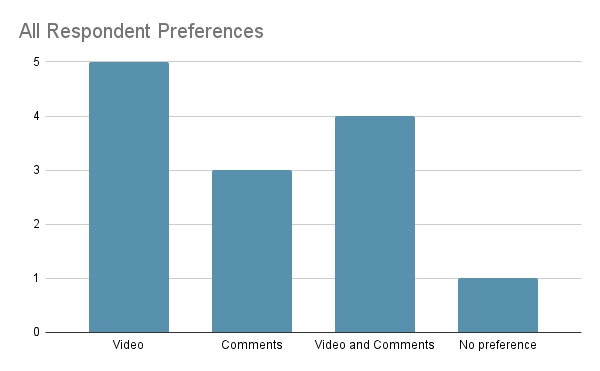

General responses show favor for the video and marginal comments. Of the participants, five indicated favor for video, three indicated favor for the marginal comments, and four indicated a preference for both the video and marginal comments together. One student indicated no preference between the three, and no responses indicated a specific preference for the cover page summary (Fig. 4).

Respondents sometimes elaborated on their preferences. For the singular student who indicated no preference between the different feedback forms, they stated that “videos help elaborate on comments.” Of the students who indicated preference for both the video and marginal comments, one noted that the video was “conversational and displayed where in the paper the comments corresponded to” and that the marginal comments “displayed areas for correction or review.” Another response that indicated a preference for both types commented on the connection between the two, stating “I like the video walking through the process of the edits and then the margins to remind me of the changes to make as I am editing.”

When explaining their preference for the video or the comments separately, students would often comment on what they found valuable about that feedback. One student, who preferred the video feedback, explained “it was better to understand what exactly they wanted me to do to fix my draft. It also was useful because it allowed the tutor to explain more in-depth.” One student who preferred marginal comments explained “they give me the exact changes they think I should make,” echoing a similar response that stated they prefer “Marginal comments, because I can see exactly where needs to be fixed.” One respondent explained why other feedback types weren’t as helpful to them as the comments, stating “The video and cover page give me a summary of the whole document, which is not as helpful for fixing smaller grammar errors.”

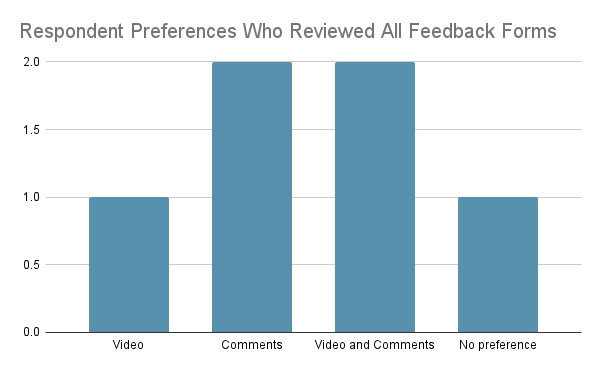

Feedback preference was also considered for the six students who had taken the time to use all forms of feedback. When reviewing the preference of the six specific students who used all three forms of feedback, two preferred marginal comments, one preferred the video, two preferred both marginal comments and the video, and one indicated no preference (Fig. 5).

Various trends were observed in the answers to what students found helpful in their tutor’s feedback. Common answers include value behind tutor feedback on grammar and structure, with six responses mentioning grammar and/or structure in their explanations. Another area of appreciation for tutor feedback was the tutor’s ability to ensure assignment requirements were met, with two responses specifically mentioning this appreciation. Other responses had no overlap; these responses included appreciation that the tutor provided multiple options for approaching suggested revisions, helped with following a citation style, provided honest feedback, and generated ideas for additional content in the essay.

Many students had no feedback to provide on what their tutor could have done differently, though two students mentioned that they wished the tutor had provided marginal comments. But by using the Writing Center’s client report forms, I was able to review these students’ feedback from their Drop-Off appointments and note that their tutors had included marginal comments on all submitted papers. Another two students mentioned that they wanted more elaboration from their tutor. One explained that, in their specific appointment, their tutor recommended rewording a sentence, and the student wished they would have provided ways to approach rewording that sentence. The second student simply said that they “wish [their tutor] would have gone more in-depth while discussing things that ‘need more.’”

Responses to participants’ overall experience with Drop-Off Essay Review were generally positive. In total, 12 students responded positively. The singular student who responded negatively simply stated that they did not “have a good experience” but did not elaborate further.

Finally, most students did not provide any feedback for what could be done to improve Drop-Off in the future. Only three students commented on the possibility of a change to Drop-Off. Of the three students, one recommended incorporating more specific examples into Drop-Off feedback, one suggested incorporating different genres into Drop-Off such as specific genres for history papers, medical papers, creative writing papers, and so on, and one simply responded that “going into the writing center is more beneficial.”

Analysis

Demographic results bring an interesting topic to the table, which is that students don’t solely use asynchronous methods of tutoring because in-person tutoring would be out of the way for them. While many students did cite convenience as a reason for utilizing Drop-Off in this survey, the results also show that most students utilizing Drop-Off live on campus. As 10 students live on campus, only three participants would have to drive to campus for their appointments. So, this statistic likely demonstrates that having easy access to in-person tutoring does not simply make students more likely to use such services over remote options.

Furthermore, the repetition in responses that students chose Drop-Off because of a lack of necessity for in-person tutoring potentially shows that students believe that certain situations call for different types of tutoring. Most students indicated that they only needed feedback on their grammar when noting that in-person tutoring didn’t feel necessary. Another student noted that they did not have any questions about their feedback or paper or else they might have opted to have an in-person or Zoom appointment instead of a Drop-Off appointment. These responses show a likelihood that students perceive different types of issues as needing to be addressed face-to-face, such as larger topic issues, whereas smaller writing problems like grammar and mechanics are not considered necessary areas to be discussed in-person.

Students’ favor for tutor feedback of structure and grammar further highlights the perceived usefulness of asynchronous tutoring for students. The placed value in these specific areas of feedback by their tutors, indicated by students’ response to what they liked about their tutor feedback as well as included in reasoning for which feedback types students preferred, shows that students likely view Drop-Off as a helpful tool for checking their grammar and formatting in their papers. This feedback also potentially shows that students are more comfortable with getting feedback on these smaller topics in an asynchronous format.

Respondents’ answers to what they sought help with in their appointments further give insight into student perceptions of the use for Drop-Off. Students often indicated that they wanted tutor feedback to focus on grammar and mechanics, correcting citations, and ensuring assignment requirements are met. These most common responses highlight the types of feedback that students feel are suited for the asynchronous format.

The lack of responses to this question also potentially highlights the types of feedback that students feel are not suited for the asynchronous format, and that may require a face-to-face appointment instead. No students wanted help locating or integrating sources for their paper, only one wanted help designing a visual assignment, and only two sought help understanding the assignment or developing and revising a thesis statement. This data shows that students do not feel that Drop-Off is suited for appointments that need help with brainstorming; they, however, feel more comfortable utilizing Drop-Off strictly for essays rather than on visual assignments such as presentation slides.

Results also indicate a value that stems from mixing different feedback methods together. Both students who had utilized all three feedback methods and students who had only looked at a few tended to comment on the usefulness of the video and marginal comments together if the student reviewed both feedback types. Students even explained in multiple cases that the video often helped elaborate on the marginal comments, allowing students to make sense of the written feedback provided to them by their tutor.

This relationship between the two feedback methods suggests that, in asynchronous settings such as Drop-Off, the combination of feedback types makes up for the lack of interaction between students and their tutors. The video feedback within Drop-Off appointments may provide students with that sense of connection with their tutor as well as providing the means of feedback that is more familiar to in-person appointments, which is spoken feedback. Therefore, the video allows the asynchronous appointment to move closer to what a student experiences in face-to-face tutoring. While the two still clearly have their differences, and face-to-face still provides different advantages that are still missing from Drop-Off, such a combination of feedback types makes this format of asynchronous tutoring more understandable to students while still providing that aspect of flexibility and convenience that comes with the asynchronous format.

Results also indicate that Drop-Off could be altered to make feedback more accessible to students. Two separate participants in this study indicated a lack of marginal comments from their tutor’s feedback despite the Writing Center’s client report form data showing that these students’ appointments did contain marginal comments. As tutors utilize Microsoft Word to leave comments, the settings in this program must be selected to show all comments on a document in order for students to view tutor comments, so these students likely had the wrong settings and did not know to turn the comments on.

It is interesting to note that Buck and others encountered the same issue with one of their participants in their study, who did not know how to make marginal comments visible in Microsoft Word and as such was unable to review their tutor’s feedback. After this discovery, they advise that any institutions with a similar style of feedback should incorporate a video tutorial showcasing how to turn comments on in Microsoft Word (2021). While the appointment confirmation that students receive via email explains how to make marginal comments visible through Microsoft Word, these instructions are not included in the actual feedback that students receive. Many students likely do not read the full email or might not even open it in the first place. Therefore, changing the cover page summary to include information about how to display marginal comments would likely benefit students to ensure that all feedback and instruction is easily found.

Finally, results show that students may utilize asynchronous methods such as Drop-Off to ease them into other tutoring situations. While the majority of students in this survey indicated prior experience with face-to-face options, a substantial portion of students also indicated that they had not yet experienced in-person or Zoom tutoring. As the vast majority of students in this survey were also freshmen, they are still adjusting to college life. Many of these students may be out of their comfort zone, and going to meet with a stranger to discuss their writing may not be something that they feel comfortable to do while still settling in. One participant in this study even specifically stated that the lack of human interaction was a large factor in selecting a Drop-Off appointment over in-person or Zoom tutoring. Thus, it is possible that Drop-Off and other asynchronous tutoring options provide a more comfortable space for students to familiarize themselves with tutoring.

Discussion

Various findings connect back to past research. One such finding is in the reasons why students opted for Drop-Off tutoring over in-person alternatives with time and convenience being large factors. This finding is in agreement with findings by Bell, Chewning, Bell et al., and Wolfe and Griffin, though convenience is often either grouped in with reasons of time or described as freedom instead.

Another similarity between this study’s findings and existing literature is in how online options provide the ability to reach more students. Barron et al. and Bell et al. both point out that online options have the potential to reach new populations who might find in-person options to lack inclusivity. As 5 out of 13 (38.5%) respondents in this survey indicated that they had not utilized face-to-face options, this fact can also highlight how asynchronous options serve a purpose in reaching a wider audience that in-person options fail to reach. I would also suggest that, based on research that asynchronous options provide more inclusivity, providing more options in feedback to students could have a similar effect. This study established that students have differing preferences, with some preferring solely written feedback, others preferring solely video feedback, and others still enjoying the combination of these feedback types. Incorporating asynchronous options that provide these opportunities allows reach to all of these students despite their differing preferences.

Furthermore, many of the findings from Cavanaugh and Song’s (2014) study in the classroom setting carried over into this study. Cavanaugh and Song’s analysis of student interaction with their professor’s feedback in different formats found that students valued the written feedback for the directness and specifically how this format tended to focus on the topic of grammar (p. 127). Meanwhile, students also noted that the audio feedback was better with explaining and providing examples, leading to an easier understanding of feedback (Cavanaugh & Song, 2014, pp. 128-129). The results from students utilizing Drop-Off also indicated that students had a high appreciation for comments on grammar, and those who selected marginal comments as their preferred feedback type often cited how this method is where they received grammar feedback. In addition, those who preferred both video and grammar often commented on how the video provided a better understanding of the tutor’s feedback, similar to how students in Cavanaugh and Song’s study felt the audio feedback provided more explanation and better understanding of the instructor’s feedback.

Limitations and Future Research

There were some limitations to consider in this study. First, it became clear through student responses that there was some confusion in what the cover page summary referred to in the survey. Many students indicated that they did not review the cover page summary but that they did review the video. The only way to get to the video is through a section in the cover page summary, which shows that some students may have reviewed the cover page summary without realizing.

It is also possible that students skimmed until they reached the video link, which is at the top of the cover page summary, and truly did not review the cover page summary; however, one student specified that they did not receive the cover page summary in their feedback despite also indicating that they reviewed the video feedback. This feedback shows that at least one of these students definitively misunderstood what the cover page summary was and falsely believed that they did not receive this form of feedback. Thus, the results in this study are more telling on student perceptions of the video and marginal comments feedback, and conclusions on student use and opinions of the cover page summary cannot be made.

Another limitation from this study stems from the time of the year in which it was conducted. At this institution, all freshmen are required to take a Rhetorical Communications class within their second semester. As most freshmen are in their second semester during the spring, this fact means that the spring semester is filled with many Rhetorical Communications courses. These courses are intended to teach students the basic writing skills that they will need for the rest of their college experience. These courses also require that their students regularly visit the Writing Center for appointments. Therefore, many freshmen utilize Drop-Off appointments solely to fulfill this requirement. Due to this fact, the participant pool in this survey may look vastly different from a pool from fall semesters.

Future studies on this topic should be done to further investigate student experiences with combined feedback types in other institutions. Doing so would give an insight as to how students interact with multiple feedback types in other methods of asynchronous tutoring rather than just how students who interact with Drop-Off Essay Review interact with multiple feedback types. Such studies could also explore differences between mediums as findings in this study are specific to the fact that this institution provides feedback through Microsoft Word. Google Documents is also a popular medium for writing and maintains an option for commenting, allowing it to function for marginal comment feedback similarly to Microsoft Word, so studies investigating the impact of these different mediums on student experiences could broaden beyond Microsoft Word to include Google Documents or other similar programs/applications.

Additionally, a recreation of this survey could be done at this institution in the fall semester in order to see how the semester changes results. Further, this recreation should make each feedback type more clear in order to ensure understanding from students on what feedback types they are discussing. Doing so would allow the Writing Center at this institution to better understand student perceptions of the cover page summary in Drop-Off Essay Review as this current study was unable to draw any conclusions due to lack of comments suspected to stem from confusion on the feedback type. Race and ethnicity were not included in this study but would be helpful for future studies to further analyze how asynchronous options can be more inclusive and reach different populations of students.

Finally, I suggest in this paper that incorporating many feedback types may make a more inclusive tutoring option. This possibility should be further explored in future studies to demonstrate how the reach of a writing tutoring program will differ based on the types of feedback options it provides to their students.

Conclusion

This study reaffirms previous research suggesting that asynchronous tutoring allows writing centers to reach a wider range of students, including those in minority communities that may feel uncomfortable within the physical environment. Feedback from the participants displays an increased level of comfort when receiving asynchronous feedback, which may allow more shy personalities to ease into the tutoring setting. Furthermore, the findings on multimodal feedback methods display a relationship between video and written feedback which allows students to better understand and interact with asynchronous feedback from their tutors. The usage of both written and video feedback allows tutors to expand upon their explanation to deliver feedback in a way which would not be possible without both feedback types.

References

Barron, K. L., Warrender-Hill, K., Buckner, S. W., & Ready, P. Z. (2023, January 14). Expanding writing center space-time: Tutoring modality, access, and equity. The Peer Review, 7(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-7-1-featured-issue-reinvestigate-the-commonplaces-in-writing-centers/expanding-writing-center-space-time-tutoring-modality-access-and-equity/

Bell, L. (2019). Examining tutoring strategies in asynchronous screencast tutorials. Research in Online Literary Education. http://www.roleolor.org/examining-tutoring-strategies-in-asynchronous-screencast-tutorials.html

Bell, L. E., Brantley, A., & Vleet, M. V. (2021). Why writers choose asynchronous online tutoring: Issues of access and inclusion. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 46, 2–10. https://doi.org/https://www.wlnjournal.org/archives/v46/46.5-6.pdf

Breuch, L. K. (2005). The idea(s) of an online writing center: In search of a conceptual model. The Writing Center Journal, 25(2), 21–38, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442221

Buck, C., Nolan, E., & Spallino, J. (2021). “I believe this is what you were trying to get across here”: The effectiveness of asynchronous etutoring comments. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 18(2), 33–49. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/13359

Cavanaugh, A., & Song, L. (2014). Audio feedback versus written feedback: Instructors’ and students’ perspectives. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10, (1), 122-138. https://jolt.merlot.org/vol10no1/cavanaugh_0314.pdf

Chewning, B. (2015) “The expanding center: Creating an online presence for the UMBC Writing Center. Young Scholars in Writing, 5, 50-62, https://youngscholarsinwriting.org/index.php/ysiw/article/view/73

Gallagher, D., & Maxfield, A. (2019). Learning online to tutor online. (K. G. Johnson & T. Roggenbuck, Eds.). How We Teach Writing Tutors: A WLN Digital Edited Collection. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/GallagherMaxfield.html

Silva, M. L. (2012). Camtasia in the classroom: Student attitudes and preferences for video commentary or Microsoft Word comments during the revision process. Computers and Composition, 29(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2011.12.001

Wolfe, J., & Griffin, J. A. (2012). Comparing technologies for online writing conferences: Effects of medium on conversation. The Writing Center Journal, 32(2), 60–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442393

Appendix A: Cover Page Used for Drop-Off Essay Review Appointments

Directions:

- Copy & paste this document at the beginning of a student’s work (or if student only submitted a pdf, submit this table as a separate document).

- Fill in any highlighted information with personalized information for your appointment and/or delete irrelevant information.

| Hi ___________________. My name is Lexi and I reviewed your assignment today.

You will find an overview of my feedback in this document AND feedback in the margins of your document, if you submitted as a .doc, .docx, or .rtf file. |

|||||||||||||||

| I created a short video for you…

It explains some feedback in more detail. You can view it at: [insert URL] |

|||||||||||||||

| Please note…

[Only include when relevant- Otherwise, delete] [Use when reviewing for classes/subjects outside your knowledge] When reviewing my feedback, please know I am not versed in [insert major/program], but I have provided general writing feedback. If you have questions or concerns about specific content for this assignment, I recommend reaching out to your professor. [Use if you did not complete the entire paper during your review] Tutors spend up to 60 minutes on an appointment, and I wasn’t able to finish reviewing your entire submission during that time. I reviewed up to page: ___. Feel free to make another appointment to have your assignment reviewed. [Use if no assignment prompt included] I didn’t see a specific assignment prompt included, so I’ve done my best to provide general writing feedback. I recommend reviewing the assignment prompt and rubric to make sure you have met all requirements. |

|||||||||||||||

| [Delete this section if no assignment prompt included]

I looked at your assignment prompt/instructions… I pulled out what I saw as the major requirements and noted whether or not you’ve met them.

|

|||||||||||||||

| I focused my comments on the following 3 priorities (indicated by X)…

They may be the same as or different from your selected priorities based on what I see as the most important areas for revision given the assignment expectations (if prompt was included) _ Understanding assignment and getting started (brainstorming, outlining, etc.) _ Making sure assignment expectations/requirements have been met _ Locating and/or integrating sources from research _ Developing or revising thesis statement _ Organizing and developing paragraphs/ Expanding and developing ideas _ Maintaining clear focus and organization throughout assignment _ Understanding and following a format/citation system (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.) _ Sentence level clarity and correctness (grammar, mechanics, etc) _ Design and/or organization of a visual/multimedia/multimodal assignment |

|||||||||||||||

| I think you did a nice job with…

— |

|||||||||||||||

| I think your work would benefit from considering the following…

— — |

|||||||||||||||

| Thanks for your submission to the YCP Drop-Off Essay Review service!

After revising your work, feel free to make another Drop-Off appointment. You can also access writing resources 24/7 on the ASC/WC Canvas site. |