Luke R. Beckstrand, Brigham Young University

Abstract

There has been a recent explosion of research surrounding writing centers’ relationships with the many multilingual students they serve. This research has led to the development of new resources for multilingual writers within the writing center context, including longitudinal peer-tutoring, that have yielded significant and positive results. However, much less research has taken place surrounding multilingual writers’ experiences within a composition classroom. Throughout a semester embedded as a tutor inside of two first-year multilingual composition courses, I was able to gather research and test possible applications of longitudinal peer-tutoring inside the classroom. Multilingual students need, and desperately want, writing help in all contexts. Many multilingual students flock to writing centers, who are more than happy to help, but many multilingual students’ experiences with university writing continue to take place solely within the classroom. My research indicates that a single peer-tutor embedded within the classroom can give these students the help they desire through a similar longitudinal peer-tutoring relationship that has been achieved at some writing centers.

Keywords: Writing Center, Multilingual Tutoring, Longitudinal Peer-tutoring, Classroom Applications, One-off Sessions,

Helping Multilingual Writers

Background: Challenges Multilingual Students Face

Some of the most consistently challenged people in universities are multilingual students. I have had the opportunity to work with many of these students, a majority of whom were either international students or immigrants. Several of them have confided in me how trying it is to move to the U.S. and the complicated difficulties they face: saying goodbye to everything familiar, learning a new language, adapting to a new culture, trying to work and educate themselves, and doing it all while feeling painfully alone. Despite these challenges, attending college and pursuing an education is a dream come true for many of them.

Yet this dream comes with its own assault of daunting challenges. They arrive at the university with varying levels of language skills and are still expected to produce writing on the level of their native peers (Mitch & Kennell, 2020; Watkins et al., 2023). Having lived in Argentina for various years, I consider myself fluent in Spanish, but I could never write an essay in Spanish that could ever rival that of a native speaker’s ability. This gives me empathy for the difficulties of these multilingual students and the desire to see them with the help they deserve. Fortunately, as the field of second language writing grows, many universities have begun addressing the needs of multilingual students (Matsuda, 2012). Even so, considering these students’ valid needs, there remains a necessity for more comprehensive faculty training and more resources to be available to the students (MacDonald, 2007; Bruce & Rafoth, 2016, de Kleine & Lawton, 2015).

The central question of all student-centered research, irrespective of the context, remains the same: how can we best help the student? Writing centers have boldly charged through the difficult and sometimes ambiguous fog that surrounds this question, creating a helpful corpus of data for us to work with. Of course, the question of how we can best help students becomes even more nuanced and complex when taken to the world of multilingual students and their wide variety of language learning and cultural backgrounds.

What is Multilingual?

In this paper, I have chosen to use the term multilingual. Initially, this appears to be a term for anyone who speaks multiple languages. While this is true in a broad sense, in this paper, I am referring to anyone whose only native language is not English. Over the years, a host of terms have been coined and given to different demographics of language learners, including ESL, L2, Gen 1.5, and bilingual (Fitzgerald & Amendum, 2007; Flores, Kleyn, & Menken, 2015; Friedrich, 2006: Otte & Mlynarczyk, 2010; Bruce & Rafoth, 2009). All these terms can be helpful, especially when used to specify who is being discussed. For the purposes of this paper, multilingual will be used as an umbrella term to all the rest. I will use it to refer to any student who is speaking or writing in a language that is not their only native tongue (Alvarez, 2018; Hanci-Azizoglu, 2020; Vieira, 2022).

I decided to use multilingual because I feel that it is the most constructive and least ambiguous term available, especially considering the demographic I was working with for my research. Many of the students I interacted with were immigrants with varying amounts of experience in the U.S. Some had been in the country for only a handful of weeks, others a few months, and others a couple of years. But there were also students who had come to the U.S. at a very young age, or were even born and raised in the U.S. but grew up in families that spoke more than one language, making English one of several “native” languages (Vieira, 2022). I also worked with many international students—students who grew up in other countries and were only living in the U.S. to attend university (de Kleine & Lawton, 2015). Multilingual encompasses students in all the possible circumstances as well as highlights these students’ strengths. The ability to communicate in multiple languages is an impressive and helpful feat and should be celebrated!

The goal of my research was to discover new ways of structuring aid for these multilingual writers in a university setting. Of course, before we can properly address that issue, we must first understand what kind of help they actually need and want.

What do Multilingual Students Need?

Grammar: The Priority or a Priority?

Some existing research suggests that multilingual students primarily require (and desire) grammatical aid (Eckstein, 2018; Severino, Swenson, & Zhu, 2009). Much of the data indicates that multilingual students wish to sound more like their peers, more “native” in their writing, and that they believe the key to unlocking this wish lies in improving the grammar of their papers (Denny, Nordlof, & Salem, 2018; Denny & Towle, 2017).

However, recent research has challenged the idea that grammar is the dominant priority for multilingual students, suggesting instead that multilingual writers also want help with a wider set of writing and writing adjacent skills, such as understanding their assignments, learning different rhetorical patterns, and expanding their vocabulary, among others (Nakamaru, 2010, Kennell, 2019; Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Harris & Silva, 1993). This should give us pause, force us to reconsider what kind of help we are offering multilingual students, and make us wonder about the best possible resources for them.

Longitudinal Peer-Tutoring: Understanding Multilingual Students’ Goals

The writing center at Brigham Young University (BYU) recently piloted a longitudinal program in which multilingual students were paired with tutors for the course of a semester. Within this program, tutors and students met once a week for an hour-long session, fostering a helpful and collaborative tutoring relationship between the consultants and the students. A research group that I participated in analyzed differences between the goals made by multilingual students inside the program, and those that did not participate (instead visiting the writing center intermittently and working with different tutors most of the time). This research is currently undergoing the process of publication (see Watkins et al., 2023), and the results of the study support the emerging notion that multilingual students do really need, and want, a wide variety of help when it comes to their writing skills. For the students within the longitudinal program, grammar remained a priority, but it was surrounded by the desire to improve skills, such as the speed of their writing, reading comprehension, assignment comprehension, speaking, time management, procrastination, motivation, study skills, and research skills, among others, all of which have nothing, or very little, to do with grammar (Watkins et al., 2023).

This study demonstrates that the range of writing skills that students wish to improve are much wider and more nuanced than was previously believed. Because of this, the writing center at BYU has acknowledged that perhaps occasional one-off sessions may not be entirely sufficient for all multilingual students and has begun advocating for their longitudinal program.

The Proper Setting

All the research suggesting that multilingual students primarily want grammatical aid is well founded. There is a host of research indicating that most multilingual students primarily ask for grammatical help when visiting the writing center. However, most of this research is based on one-off sessions. One-off sessions at writing centers generally last half an hour to an hour, where the student meets with a tutor they may or may not have worked with before, and they get as much done in that time as they can. These sessions typically begin with an agenda-setting conversation, where the tutor asks the student what they would like to accomplish in their short time together. Having only half an hour to an hour, the students are forced to triage the needs of their paper. It is not surprising that grammar almost always rises to the top of the hierarchy of their needs. If multilingual students wish to sound more like their peers and avoid what they feel might be embarrassing mistakes, focusing on grammar feels like the obvious choice.

As stated before, my research group’s study at BYU offered evidence suggesting that multilingual students do indeed have other priorities. However, one of our research group’s major findings was that multilingual students are only interested, and able, to work on a deeper and wider variety of goals when facilitated by the proper setting. This “proper setting” includes being free from time constraints and having the ability for the tutor to coach and collaborate at length with the student (Watkins et al., 2023). Both of these requirements can be met through longitudinal peer-tutoring. This leads to a tutoring relationship that offers much more inclusive and holistic help to the students and has yielded significant student satisfaction for BYU’s writing center’s pilot program (Watkins et al., 2023).

Classroom Applications

As heartening as all of that is, that sort of longitudinal peer-tutoring for multilingual students mainly only exists, as mentioned before, within writing centers, and even programs like BYU’s are still in their natal stages of life. Fortunately, the advantages of embedded peer-tutoring in general are being recognized more and more, and several embedded peer-tutoring programs exist across a myriad of courses, including classes of science and engineering such as those discussed in the Journal of College Science Teaching (Dansereau et al., 2020). As the field of second language writing continues expanding, hopefully the incredible value of an embedded tutor specifically for multilingual composition classes will become increasingly acknowledged. Optimistically, this will inspire university support for many such embedded tutoring programs for multilingual composition courses, especially considering that multilingual students need and want this kind of help.

This knowledge was the motivation behind the research that I recently conducted. As an embedded tutor for two first-year multilingual composition classes from January to April 2023 at Brigham Young University, I had the opportunity to test firsthand what the possible applications of such longitudinal peer-tutoring could be within the classroom setting. My hope was to create the proper environment in which multilingual students could not only identify broader goals, goals that stretch beyond grammar, but also have the time and ability to work on improving them.

Methods

An Embedded Tutor

In 2022, I had the opportunity to work as an embedded tutor in various ELING 150 classes, which is the first-year composition class for multilingual students at BYU. This gave me experience working with the professors and, on occasion, the opportunity to act as a substitute professor and teach some of the class material. During the semester, the professors required their students to meet with me a few times to offer one-on-one help for their papers. These meetings occurred sporadically, with some students meeting with me only once and a few not at all.

Between January and April of 2023, I was able to take advantage of my continuing position as an embedded tutor to conduct some research. During that time, I was an embedded tutor for two separate ELING classes with different professors and different (though similar) curriculums. Though several of the assignments were nearly the same, many were completely unique to each class. One of the classes had 12 students while the other had 17, giving me a total of 29 students to work with during the course of the semester. These 29 students designated themselves as “multilingual” by signing up for the course, which indicates that it is “for non-native English speakers only.” On the first day of the class, the professor always re-announces this, and any native speaking English students who signed up for the class by accident are asked to leave, transferring instead to the mainstream section of first-year composition writing. Any student who feels that their situation is ambiguous, having grown up as a Gen 1.5 student or something of a similar situation, is left with the choice of whichever class they would like to attend.

At the beginning of this semester, I met with both the ELING professors as well as the administrators of the writing center and we discussed how I could be better utilized as an embedded tutor within the classroom. I described what my experience had been like up to that point, and the professors expressed their concerns and priorities. In the end, I asked the professors of these two ELING 150 classes if they would be willing to experiment with me more consistent, longitudinal peer-tutoring within the classroom. I asked them to require their students to meet with me once every two weeks, giving me the opportunity to tutor each student one-on-one seven times—every other week through a fifteen-week semester.

Only one of the professors indulged my experiment in its entirety. The other professor, instead of requiring the students to meet with me every two weeks, required her students to meet with me once for every major writing assignment they had, with an additional meeting at the beginning of the semester for goal-setting and again at the end of the semester as a reflection. This resulted in the students meeting with me five times—two less than the other class.

These circumstances worked well for my research. It gave me two groups to work with that had different variables. As an embedded tutor and as a part of my research, I wanted to attend the classes once per week to get to know the students as well as to be present during the professors’ explanations of the class assignments. This helped me answer specific questions the students may have had when coming to me during our consultations.

The Research

Having been an embedded tutor for these classes before, I was able to concretely track the differences between my experience in 2022 (where the students consulted with me occasionally and sporadically) and my experience in 2023 (where the students met with me much more often and consistently). Being able to compare these experiences was instrumental for me in understanding exactly how helpful I was for the students.

The first and one of the most significant differences that I immediately took advantage of was my ability to make my time with the students more purposeful. During my time as an embedded tutor in 2022, my sessions with the students would most often play out much like a one-off session from the writing center. The student and I would have about half an hour together, they would describe to me the kind of help they wanted, and we would get to work. However, having more time with the students in 2023, we were able to make much more thorough use of our time. For example, the first consultation I had with all the students, regardless of which class they were in, constituted an extended “agenda setting” session for the semester. This mimicked BYU’s writing center’s longitudinal multilingual program exactly, seeing as the first consultation for the students in that program was also focused on creating goals for the semester. During this agenda setting consultation, we discussed the students’ relationships with writing and what they were hoping to accomplish that semester, not only with me as their tutor, but within the composition classroom. We set a minimum of three goals together, giving me a total of 87 goals.

After collaborating with the students about these goals during our first consultation, they went on to write essays for their classes on their own time, and then returned to me, either on a biweekly basis or once for each assignment. The hope of my continued tutelage of the students was to help them progress in the goals they set with me at the beginning of the semester by using the classes’ assignments as a vehicle for that learning.

Each of my consultations with the students was slated for a half an hour, though many were slightly shorter than this, and several were much longer. I made a sign-up sheet on Google Sheets that was given to the students indicating which times I was available to meet with them, and they were responsible for putting their names in at the appropriate places. At the time of the consultation, I sent the students a Zoom link via email for the meeting. If none of my time slots worked for certain students, they also had the option to email me personally to set up an individual time to meet.

With only a few exceptions, the students were impressively responsible in their signing-up to meet with me. Of course, having these consultations be a part of their grade was an excellent motivator. However, many of the students met with me more than was required, which was a pleasant and welcome surprise.

All the meetings, with a few exceptions, were held over Zoom. This was to alleviate the need for both the student and I to find a physical place to meet and made the whole process significantly easier for me. If the students came with writing they wanted me to review, they would share their screens with me, and we would read through their work together, out loud, and discuss the student’s concerns, what improvements could be made, and clarify any points of the rubric. This collaborative tutoring process mimicked almost exactly the kind of consulting available at writing centers, with the exception that I was intimately acquainted with the students’ professors and most of the class assignments.

Results

The main advantage of longitudinal peer-tutoring in writing centers was being free from time constraints, allowing the tutors and students to work on goals that exceeded grammar. This was accomplished by the tutors and students being paired with each other and meeting for an hour-long consultation once a week throughout the course of a semester. In exploring what the classroom applications of this could be, I believe I have found some very helpful answers.

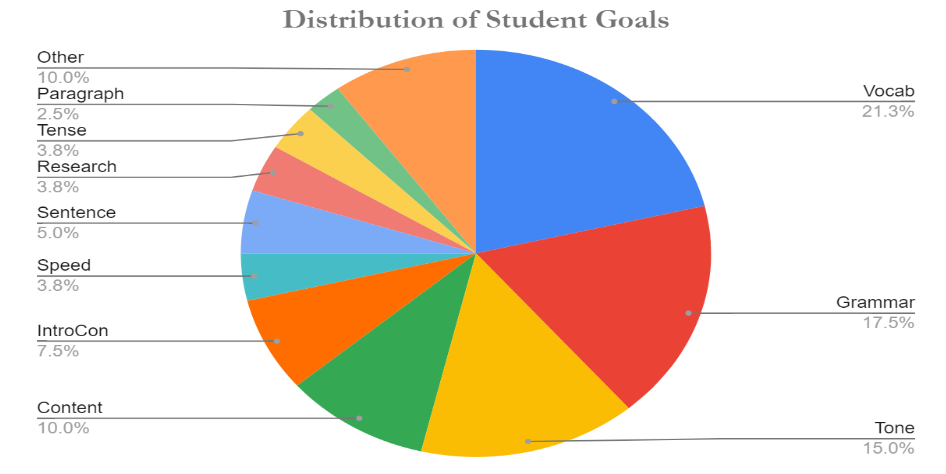

By myself, as a single tutor with 29 students to work with, I was able to preserve in a classroom almost everything about longitudinal peer-tutoring that occurs in the writing center. Evidence of this lies in the goals the ELING students made with me. I analyzed these 87 goals and created a set of deductive codes to qualitatively categorize them. I used that data to create a distribution chart as featured in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Figure showing distribution of coded categories

As we can see, many of the students did set grammatical goals, but they also set goals pertaining to vocabulary, writing speed, research comprehension, and other writing and writing adjacent goals reminiscent of the goals set by the students in BYU’s writing center’s longitudinal program.

Yes, grammar remains a major priority, but in this longitudinal setting, we are able to see other goals come to the surface, including expanding their vocabulary (a lexical goal), creating professional tone in their writing, and honing their ability to create sufficient, relevant content. The ability to identify and work on these goals are the advantages that BYU’s writing center found that come from longitudinal peer-tutoring, and I was able to preserve them in the classroom setting, even with students that I wasn’t meeting with on a biweekly basis.

It is worth noting that a large majority of the students that made goals in the vocabulary section told me that the largest reason they wanted to expand their vocabulary was to improve their tone. They felt that they sometimes didn’t know the correct words or terms for certain things, or that they fell into redundant patterns because they were unable to use more elaborate descriptors. With this desire to improve their vocabulary, they were hoping to achieve greater professionality in their papers.

Comparing Longitudinal vs. One-off Goals

As I facilitated a longitudinal environment with my ELING students, I was hoping to be able to move beyond grammatical goals. As seen in Figure 1 (above), I know that I succeeded. But how much do these goals differ from normal one-off sessions goals from the writing center?

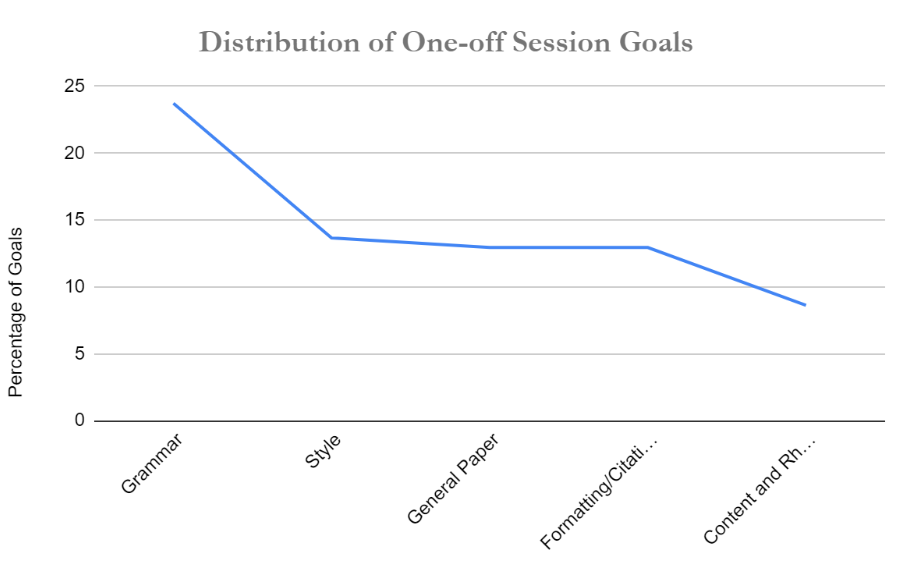

Below is a chart showing the top five most frequent goals made in one-off sessions at BYU’s writing center by multilingual students over the course of a school year (from Fall 2021 to Winter 2022). As we can see, 23.74% of their goals were grammatical, and another 12.95% were “General Paper” goals. This means the goals were ambiguous or general enough not to be categorized anywhere else, usually taken from a goal such as “I want my paper to be better.” That’s over 36% of student goals that are either purely grammatical or unhelpfully vague.

Figure 2

A line chart showing the top five most frequent goals made in one-off sessions at BYU’s writing center for multilingual students over the course of a school year

Contrast Figure 2 with the student goals in Figure 1, where only 17.5% of my ELING student’s goals were grammatical, and all other goals were helpfully specific. This shows us that a longitudinal peer-tutoring relationship is indeed the “proper setting” for students to be able to collaborate on their goals, narrow them down, and express them in specific ways.

Conclusion

I entered my research pondering this question: are there applications for longitudinal, multilingual peer-tutoring in the classroom? The easy answer I discovered was: of course! And none of the advantages of this type of tutoring need to be lost in the transition from writing center to classroom. But what exactly are the applications for longitudinal peer-tutoring in multilingual classrooms? The embedded peer-tutor. The environment I was able to create as an embedded tutor in these ELING classes was suitable for the students to be able to work on goals beyond grammar. This was also accomplished without the manpower or resources available to writing centers. I was a single tutor, embedded in two different classrooms and working with 29 students.

As stated previously, multilingual students both need and want help beyond grammar, but they seldom ask for it because of the lack of the proper setting. The ability for writing centers to offer longitudinal peer-tutoring programs to these students, to be able to foster the growth of non-grammatical goals, has already yielded great results, and this same experience can be replicated within composition classrooms. Not surprisingly, the advantages of longitudinal peer-tutoring can be very similar within the classroom setting.

Unfortunately, embedded peer-tutoring for multilingual students in a classroom setting raises a host of challenges. Beyond the evident lack of manpower and resources, the embedded tutor would also require training, both with tutoring praxis and to work with multilingual students. Once the tutor is trained, they would need university support and willing coordination from the composition professors before they could begin their embedded tutoring. All of this doesn’t even include the challenges of compensation for the tutor, which would require further university and department support.

Despite these obstacles, longitudinal peer-tutoring for multilingual students is possible, and the outcomes speak for themselves. In such a longitudinal, collaborative setting, the students can move beyond grammatical goals and have the time and space needed to work on them. This is a needed resource. Multilingual students tackle diverse and unique challenges as they face expectations “to produce professional and academic writing throughout their studies, [despite coming] from a variety of different language-learning circumstances and unique cultural backgrounds” (Watkins et al., 2023). On top of all that, specialized training is not always given to faculty and staff to help them be better equipped to work with multilingual writers in the classroom, in spite of the fact that these students frequently have valid and unique needs (Bitchener & Ferris, 2012; MacDonald, 2007; Matsuda, 2012; Bruce & Rafoth, 2016). It is therefore our responsibility to give them as many resources as we can, and while writing centers begin experimenting with longitudinal, multilingual peer-tutoring, composition classrooms should as well. My research indicates that it is not only needed but entirely possible.

References

Alvarez, S.P. (2018). Multilingual writers in college contexts. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy. 62(3), 342-345.

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center: Towards an evidence-based practice. Peter Lange.

Bitchener, J., & Ferris, D. R. (2012). Written corrective feedback in second language acquisition and writing. New York: Routledge.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth B. (2009). ESL writers, a guide for writing center tutors second edition Boytnton/Cook Publishers Inc.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth B. (2016). Tutoring second language writers. Utah State University Press.

Dansereau, D., Carmichael, L., & Hotson, B. (2020). Building first-year science writing skills with an embedded writing instruction program. Journal of College Science Teaching, National Science Teaching Association. 49(3). https://www.nsta.org/journal-college-science-teaching/journal-college-science-teaching-januaryfebruary-2020/building

de Kleine, C. & Lawton, R. (2015). Meeting the needs of linguistically diverse students at the college Level. CRLA College Reading and Learning Association.

Eckstein, G. (2014). Ideal versus Reality: Student expectations and experiences in multilingual writing center tutorials. University of California.

Eckstein, G. (2018). Goals for a writing center tutorial: Differences among native, non-native, and generation 1.5 writers. Writing Lab Newsletter, 42(7–8), 17–23.

Fitzgerald, J., & Amendum, S. (2007). What is sound writing instruction for multilingual learners? In S. Graham, C. A. MaCarthur, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Best practices in writing instruction. Guilford Press. 289–307.

Flores, N., Kleyn, T., & Menken, K. (2015). Looking holistically in a climate of partiality: Identities of students labeled long-term English language learners. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 14(2), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15348458.2015.1019787

Friedrich, P. (2006). Assessing the needs of linguistically diverse first-year students: Bringing together and telling apart international ESL, resident ESL and monolingual basic writers. Writing Program Administration, 30(1.2), 15-35. https://associationdatabase.co/archives/30n1-2/30n1-2-friedrich.pdf

Hanci-Azizoglu, E., & Kavakli, N. (2020). Futuristic and linguistic perspectives on teaching writing to second language students. Mediterranean University.

Harris, M., & Silva, T. (1993). Tutoring ESL students: Issues and options. College Composition and Communication, 44(4), 525–537.

Denny, H., & Towle, B. (2017). Braving the waters of class: Performance, intersectionality, and the policing of working class identity in everyday writing centers. The Peer Review, 1(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/braving-the-waters-of-class-performance-intersectionality-and-the-policing-of-working-class-identity-in-everyday-writing-centers/

Denny, H., Nordlof, J., & Salem, L. (2018). “Tell me exactly what it was that I was doing that was so bad”: Understanding the Needs and Expectations of Working-Class Students in Writing Centers. Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 67-98.

Kennell, V. (2019). Writes well with others: Developing L2 expertise in writing center tutors. Purdue University

MacDonald, S. P. (2007). The erasure of language. College Composition and Communication, 58(4), 585–625.

Matsuda, P. K. (2012). Let’s face it: Language issues and the writing program administrator. Writing Program Administration, 36(1), 141–163.

Mitch, H. & Kennell, V. (2020). Working with multilingual student writers, A Faculty Guide. Purdue Writing Lab.

Nakamaru, S. (2010). Lexical issues in writing center tutorials with international and US-educated multilingual writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 19(2), 95—113.

Otte, G., & Mlynarczyk, R.W. (2010). The future of basic writing. Journal of Basic Writing, 29(1), 5–32.

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions… decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147–171.

Severino, C., Swenson, J., & Zhu, J. (2009). A comparison of online feedback requests by non-native English-speaking and native English-speaking writers. Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 106–129.

Vieira, K. (2017, August 24). An introduction to multilingual writers at UW-Madison. University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/wac/an-introduction-to-multilingual-writers-at-uw-madison/

Watkins, K., Stegman, H.B., Fox, E., Beckstrand, L., Eckstein, G., & Gardner, T. (2023). Writing without constraints: How multilingual writers’ goals expand in longitudinal writing center settings. Unpublished manuscript.