Miranda Zammarelli

John Beebe

Introduction

While Writing Centers (WC) are not remedial services, they do most often target students who lack the resources that form good writers and strong communicators. Welcoming students, particularly those intimidated by the writing process, even to simply enter Writing Centers remains a central challenge for WCs to overcome. Discourse around WCs’ pedagogy deliberates greatly on how best to ensure that the students who need the most help feel comfortable enough to work intimately with a tutor in a session and, if necessary, return for another. We question designs for Writing Centers that produce atmospheres which seem more suited to students who already feel confident in their writing skills. Our concern is with a WC’s capacity to perpetuate the alienation of students with its physical design before it can accommodate them with its pedagogy. For a service that requires physical entrance into a WC, the challenge of welcoming students revolves around creating a space suitable for students of all skill levels and backgrounds.

Stefanie Sydelnik, Associate Director of the University of Rochester’s Writing Speaking and Argument Program, defined welcome for her WC as, “making tutoring accessible to different students” (Sydelnik, 2018). In our pursuit of a more efficient definition for a WC’s purpose, we began to compare WCs to therapist’s offices, as both require a professional workspace that allows for informalities between the professional (the Tutor or Therapist) and the client (either a patient or a visiting student). While Sydelnik reminds us that “tutors are not therapists,” she acknowledges that, “because we have to say that so often, it shows how much [that comparison] can encroach.” The popularity of the therapist analogy informs our understanding of how WCs generally appear to a university campus, as places where students go to ‘fix’ their problems in a process affiliated with personal struggles and awkwardly intimate conversations. To welcome students, WCs require a premeditated design that will not alienate or discomfort students. Effectively achieving a comforting WC is difficult considering WCs’ roles as sites of academic progress. Comfort, however, does not exist in opposition to the purpose of WCs. While features of comfort may distract students from the purpose of a WC, they also have the potential to emphasize a WC’s purpose and functionality.

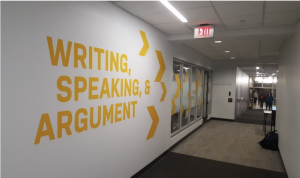

A WC’s goal to productively welcome students is reflected in the University of Rochester’s recent remodel of its WC to have multiple spaces with distinct physical designs. In our research, we investigate the effect multiple different physical designs has on a WC’s ability to welcome students and foster productive writing sessions. We discuss the decisions and goals for our writing center’s spatial redesign as we analyze student surveys to quantify the performance of the University of Rochester’s WC in welcoming tutors and tutees. Based on our observations at the University of Rochester, we argue in favor of spatial designs that feature multiple locations and atmospheres for their potential to welcome more students than a singular location. In this paper, we define physical qualities of the writing center that reinforce a welcoming conversation between tutor and tutee, what we call a “student interface” and identify points where its physical design alienates students with the goal of offering insight into a spatial design idealized to welcome students.

Interface

To describe the unique dynamic of interactions between tutor and tutee that stem from the different roles of these two parties in a tutoring session, we use the term “interface.” It functions as an indication of the power dynamics that dictate a writing session. Tutors and tutees do not truly sit down as equals. The fact that tutors hold power over the development of a session is evident in that they are available for a specific, limited, and productive purpose. As this purpose is carried out to completion, so the tutor-tutee relationship ceases (Handbook, 2014-2015). This term considers the power dynamics and distance between Writing Centers’ parties as a feature of the writing session, which lends itself well to describing the Writing Center’s spatial effects on the tutor-tutee relationship and their interactions. Condensing this dynamic into a single term offers a shortcut to understanding a writing session that allows us to emphasize the effects of space on that session.

For example, we recall waiting in a Writing Center’s lobby at the University of Rochester, listening to a conversation between two Writing Fellows (undergraduate peer writing tutors at the University of Rochester) from the opposite end of the hallway. A potential tutee looking for help walked in the door and heard the chatter. She hesitated, concerned that there was no tutor available in what sounded to all of us like a busy office, until another tutee walked straight through the lobby space and down the hall. Confused, the rest of us followed the other tutee and found the Writing Fellows casually talking, available to help tutees. They laughed and apologized for the conundrum; while we had waited in the lobby, the tutors had been waiting for a tutee to come back down the hallway for a session.

In this story, the shape of the WC’s space interrupted the formation of any interface for a session. The potential of the tutor and tutee to comfortably interact was diminished by the physical separation of two parties caused by the hallway. Two sessions were almost preempted by the confusion caused by the physical design, which could have allowed for the sessions to begin with greater ease. If we viewed a writing session as the singular unit that interface describes, we could have moved beyond the scope of the session to notice the effects of the physical design that caused the problem we observed in this story. Adopting the perspective of the interface allows us to view the session from the outside as well as from within in order to more comprehensively understand and react to the unique challenges of facilitating individual writing sessions both as individuals and as an organization.

Defining Space

To understand the effects of physical Writing Centers on the student interface, we first must define space in the context of the interface. Using Lefebvre’s (1991) The Production of Space, we believe that space is a social product. This means space, “serves as a tool of thought and of action; that in addition to being a means of production it is also a means of control, and hence of domination, of power” (Lefebvre, 26). As a result of space, a power dynamic is produced between tutor and tutee in addition to the dynamic produced by the writing process enforced within the interface. Space critically influences the established power dynamic by the concrete foundations of the space, such as hallways and rooms, and configurations including different chair positions, the distance between the tutor and tutee, or the placement of the written work on the table, which can positively contribute to producing an improved piece of writing.

As the session continues in time, power dynamics become more ingrained. Lefebvre theorizes time’s role in production and space by writing, “all productive activity is defined less by invariable or constant factors than by the incessant to-and-fro between temporality (succession, concatenation) and spatiality (simultaneity, synchronicity)” (Lefebvre, 71). The power produced through space is generated by temporal reasoning as tutees become more invested in the session. Time is necessary for the session to continue while the space aids in the success of the productive thought of the session. The product of these two factors, the time of the progressing session and the thought of the students, allows for the student’s temporal reasoning, decisions made during the session, to develop in space. Thus, space is a power produced in the interface through time, which can be transformed into the empowerment of the tutee as they believe in their writing abilities; however, space’s power could alienate potential tutees.

In order to explore the potential for the interface to alienate students, we apply concepts from God Is Red by Vine Deloria Jr. to our spatial analysis. Our purpose in employing this theory is to assess the ways that we may take European models of knowledge for granted as we shape our pedagogy and control the form of the interface in Writing Centers. Deloria (1973) writes of the focus of European models of knowledge and progress as being intrinsically linked to a narrative divorced from the environment in which it functions, and instead intertwined with a mythic sense of social progress not closely linked with an existent reality at all. European epistemology dependent on a linear temporal form of reasoning, including Lefebvre’s, operates on a severed link to the space inhabited by the practitioners of a given epistemology. In terms of educational systems, the alienation from space of the narratives central to a teaching practice isolates the knowledge provided by these practices from the reality of the atmosphere in which they function. This feature of temporal reasoning makes mythic concepts of progress easily injectable into the pedagogy of WCs, which otherwise oppose progress driven models of education.

Rather than depending on a solely temporal model, Indigenous epistemologies focus on spatial-historical reasoning. Spatial models of thought have many advantages for tutees. We theorize that it is the influence of European cultural tradition that puts pressure on students to perform specifically for progressive self-improvement in the form of higher grades. Part of carefully constructing the spatial design of WCs is deliberating on the potential socio-cultural influences in the designs of WC spaces on university campuses. Beyond simply serving students who struggle with traditional pedagogical forms, incorporating indigenous thought into our education system makes WCs more available to students who would historically have been excluded by cultural barriers; this would include indigenous students, the least represented minority group on most university campuses nationwide.[1]

Interestingly, a design that focuses the rhetoric of WCs towards letter-grade improvement already goes against common WC models of education, largely because WCs particularly served students who struggle to perform within university education systems (Sunstein, 1998). We believe that approaching the design of a WC with a focus on space as a site of learning, rather than as a site for delivery of a narrative, links students better to the space and focuses them away from academic progress and more towards personal growth, understanding, and awareness.

Methods and Results

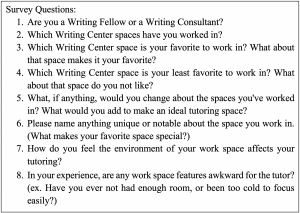

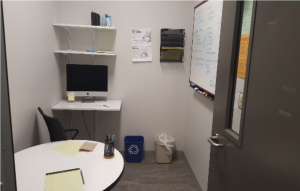

We focused on surveys we conducted in a tutoring training course, which was completed by 15 Writing Fellows, undergraduate writing tutors at the University of Rochester, and six Writing Consultants, graduate writing tutors at the University of Rochester (Figure 1). There are currently three active writing spaces and one inactive space. 95% of those surveyed worked in G-122 (Figures 2-4); 51% worked in the Susan B. Anthony dorm (Figure 5); 33% worked in Carlson Library, a currently inactive space (Figures 6-7); 33% worked in Genesee Hall (Figure 8).

Overall, the least favorite location was Carlson Library. We speculate there are many reasons for tutors disliking Carlson Library. It is known for being a far walk from on-campus dorms compared to the three open locations. Surveyed tutor one acknowledged that “it was so far and no one ever came in.” Surveyed tutor two claimed that because of the clear panels surrounding the space, “other people could easily look in and watch the session…so there was not really any privacy within the space.” The space also had a revolving location within multiple office spaces. The movement could be confusing to tutees looking for a consistent spot to receive help.

Tutors identify the Susan B. Anthony dorm as their least favorite active Writing Center because it is too dark, sessions are too close together leading to a feeling of lack of privacy, and tutors face a blank wall while working. Tutor three responded to the survey saying that “the lights are also really dim in that room which also makes it really depressing.” Tutors felt that all spaces would benefit from more decorations and lamps because they made it feel like home. Surveyed tutor four, referring to G-122, requested to “add more decorations and softer lighting… the rooms are too stark right now with the un-decorated white walls.” Decorations relevant to generating a comfortable environment were mentioned multiple times, even for the most preferred locations.

Ultimately, tutors preferred more confined spaces that offered more privacy to the open spatial configuration characteristics of the Genesee Hall Writing Center location. As reported by many tutors surveyed, G-122 is the favored space even with its flaws because of its privacy. Tutors expressed difficulty navigating and focusing in the busy and largely unstructured room, and many reported feelings of anxiety over sessions that stemmed from sensations of exposure elicited by open space, such as Genesee Hall. Interestingly, tutor anxiety was one of the most commonly mentioned concerns with the space with regard to locations with open floor plans. In response to question seven, tutor five complained, “I feel like I am a far better when I am not worrying about other tutors judging me and listening to me without my agreement.” Even tutors who are in control of their sessions felt powerless because of the lack of privacy as the sessions continued. A distinct lack of privacy may cause tutors hesitant to use certain tutoring tactics and strategies. Their hesitancy to do what they believe may be best is certainly a limitation of this design.

Discussion

In light of the work of Hadfield et al. (2003) in designing ideal spaces, the limitations of a universal design are too frequent to make employing any singular model feasible. The University of Rochester WC, for example, has some design similarities that suggest possible influence from Hadfield et al.’s model. However, this WC was forced to stray from a singular ‘ideal’ in order to reach its own individual goals. The University of Rochester WC’s process of deciding its configuration answers the question of maximizing the positive benefit yielded by the space of the Writing Center to tutors, students, and administration. To answer this question as well as possible, WCs must strike a careful balance in their design.

The risks and benefits of any design must be carefully weighed for an individualized approach to maximize the ability of the tutor to develop beneficial rapport, neutral, and personable comforts. An example of how WCs weigh these decisions can be illustrated with Carlson Library’s unsuccessful attempt to draw in more STEM students. The close proximity of the office from the locales of STEM research and education at the university did not succeed in connecting it to the academic culture it pursued. Instead, its distance proved inconvenient to tutors who worked there, marking it for denigration as a space. Its “fishbowl” quality, which arose from its occupation of a space already devoted to other tasks, created a tutoring environment that amplified the scrutiny that STEM students were perceived to hold towards WCs.

Closing Carlson Library’s space and adding a space in Genesee Hall offered a space that better welcomes all students, as the Genesee location facilitates connections of student interfaces to other accessibility resources through the nearby Center of Excellence in Teaching and Learning, a campus tutoring service, and normalizes these resources in a space where students can see that everyone is being tutored. This space’s design focuses on all students who feel uncomfortable entering a tutoring interface, but the often loud and bustling multi-purpose space can occasionally distract those who enter the interface. Though the decentralization of WCs made it more accessible to students, the nebulous form it took on as a result made it harder for many of those students to utilize it.

The concept of lacking a central location out of which a WC operates extends back through the history of WCs and the pursuit of idealizing their design. Bonni Sunstein (1998), for example, displayed many of the advantages of the spatial, and disciplinary, liminallization WCs often experience. “Moveable Feasts, Liminal Spaces,” identifies a correlation between the decentralized forms WCs take on and their hard-to-pin-down purpose. Instead of defining themselves by a central location, or the academic pieced they produce, the WCs Sunstein describes derive their identity from, “oak table[s], carpets, [..] stuffed chairs, [..] coffee pot[s] and potted plants,” all of which served as the, “stable spatial constants.” that produced what Sunstein calls a “culture” for her WC.

WC “culture” seems welcoming to the extent that Sunstein’s WC physically resonates with its pedagogy. The cultural liminality Sunstein describes positions physical WCs at the same margins as those students who struggle to find their own place in academics that so thoroughly rely on writing in one form or another. The space, in essence, cannot simply be brought to the students who need it physically, but culturally as well. In our dialogue of spatial design between Deloria and Lefebvre, the relevance of Writing Center pedagogy to its environment becomes clear. WCs are affected by a narrative of progress at an individual and structural level. A focus on abstract concepts of academic success prevents WCs from fully functioning in the interests of their students because the ability to produce academically valued writing is prioritized over student’s individual needs. For WCs to link themselves to unique students’ realities in time and space, instead of to narrative of progress, the student interface must be alienable from WCs’ historical narratives in all aspects of its design, including physical.

Recalling Lefebvre’s notion that space is a form of power produced through time, we hold that WCs should be designed to encourage tutees to enter the interface and trust their own writing skills. We must be able to deliberately shape physical Writing Centers to allow for a diversity of student interfaces that preempt student alienation to more effectively welcome the actual diversity of students who may come in for help. Integrating WCs’ interfaces in places such as residence halls and libraries provides students with productive physical place. Establishing strong identity with space makes WCs easily locatable and, optimistically, more welcoming by transforming the concept of the space into a central point dedicated to the personal development of individuals and not simply a space for tutoring sessions. This is an example of a WCs’ ability to adapt its goals to the design, and thus purpose of the space.

Conclusion

The stratifications of class, educational opportunity, race, ethnicity, nationality and language difference, and available accommodations for students disabilities all present Writing Centers with challenges in equitably serving every student in the university. In response to cultural and physical barriers to students, Writing Centers should carefully consider the effects a physical design has on all of the university’s students.

In comparison to maintaining a single WC design, multiple location designs provide students with opportunity to a diversity of places, which they are more likely to find comfortable and accessible. In our WC, we observed many elements of influence from the ideal space described by Sunstein (1998), who employs many different room designs in a central location to perform many different functions in a singular identifiable location. Though we do not find singularity of location to be necessarily good or bad, we question the functionality of the diversification of space without the anticipation of change to the interface. The utilization of multiple locations is able to achieve diversity of function with more advantages.

A diversity of available Writing Center locations could help prevent the alienation of some students from WCs. Multiple locations could reduce anxiety in the interface as students get to choose where they feel more comfortable being tutored. They may decide between a more casual space or a professional space. Writing Centers designed with variability of location allow more students to be tutored in familiar, convenient, and accessible environments. It is clear that a diversity of physical design is important because the WC has a diversity of purpose and a diversity of students.

Author Biographies

Miranda Zammarelli is an undergraduate student at the University of Rochester studying Anthropology and Brain and Cognitive Science. She currently works for the University’s Writing, Speaking, and Argument Program as a Writing Fellow.

John Beebe is an undergraduate student of Linguistics and English Literature at the University of Rochester, and proudly works in his University’s Writing Speaking amd Argument Program.

References

Deloria, Vine Jr. (1973). God is Red (3rd ed.). New York: The Putnam Publishing Group.

Fitzgerald, L., & Ianetta, M. (2016). The Oxford Guide for Writing Tutors. Oxford University.

Hadfield, L. &. (2003). An Ideal Writing Center: Re-Imagining Space and Design. Center Will Hold, 166-176.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1991). The Production of Space. (D., Nicholson-Smith trans.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Sunstein, B. S. (1998). “Moveable Feasts, Liminal Spaces: Writing Centers and the State of In- Betweenness.” The Writing Center Journal, vol. 18, no. 2. 7–26. (2014-2015).

University of Rochester – CollegeData College Profile. (2018). Retrieved October 7, 2018, from https://www.collegedata.com/cs/data/college/college_pg01_tmpl.jhtml?schoolId=117

“University of Rochester Writing Fellows Employee Handbook.” University of Rochester Writing Center. 5-6.

- At the University of Rochester, for example, indigenous students make up about 0.1% of the school undergraduate population, about one tenth of the ethnic population ratio (COLLEGEdata, 2018). ↑