Talisha M. Haltiwanger Morrison

Talia O. Nanton

“Take the spill of my words and embrace it. When I feel something it’s felt, and I will not be silenced”

The above epigraph is an excerpt from Talia’s manifesto, a piece expressing the pain and frustration of her experiences of racism, including those in her writing center, where she worked as an undergraduate consultant before being fired/forced to resign. The title stems from Audre Lorde’s (2007) piece, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” in which Lorde argues that Black women must speak their truth, as silence does not offer us protection from suffering. The experiences shared here are those of suffering, experiences which run counter to one of the central themes in writing centers’ narratives, that of a home away from home, a place that has shed its gatekeeping and regulatory history (Boquet, 1999) and made its spaces welcome to all. While it may be worthwhile to interrogate the idea of whether writing centers should be “welcoming” to all and what it means to be welcome or welcoming, that conversation becomes moot when writing centers are overtly unwelcoming and even hostile spaces for certain people.

There have been discussions of writing centers as potentially less welcoming to writers who come in for assistance with their work. In particular, Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2013) notes how writing centers and the physical identities they create for themselves, while intended to make students comfortable and welcome, are often more familiar for tutors than student writers. She echoes Nancy Grimm’s (1999) observation that tutors are often White and middle class (pp. 23-25). But what of tutors who are not White and middle class? What conversations do we engage in when a writing center becomes a harmful space for its own consultants and when the harmful nature of the environment extends beyond physical characteristics to behavior? And to whom do those consultants turn to when their anger and discomfort stems from interactions with their center’s directors?

Faison and Treviño (2017) share their experiences as women of color working in writing centers and how they have not always felt a sense of “home” in writing center spaces. As the authors write, “The WCs attempts at making itself a home by designing a space also shows [sic] a real disconnect from the body. A home is made a home through emotional labor and through acts of love, compassion, empathy.” This article shares Talia’s experiences as an undergraduate writing tutor whose Black, female body made her the target of racism in her center. She was made to feel unwelcome, uncomfortable, and even unsafe, and eventually she was forced out of her position. The two of us, Talia and Talisha, speak to one another and also to the field of writing center studies about how neither Talia, her body, nor her embodied experience were welcome in her center and about the lack of love, compassion, and empathy she felt in a center whose directors spoke often about empathy, and validity, and giving voice to others. Talia’s experiences in her center inspired a manifesto, which we also share in this piece before reflecting on its relevance to larger issues and conversations within the field.

The two authors of this piece met when one author (Talisha) interviewed the other (Talia) for a separate project. The idea for this article originated when it became clear that Talia’s experiences, her need to speak of those experiences, and for the writing center community to hear of them, extended beyond that project. Essentially, Talia, silenced by the oppression of her center and again when she lost her job, needed to follow Lorde’s advice and transform that silence into language and action. Talia had already written her manifesto, but the two authors both saw potential for further action and initiation of change through the sharing of her words and experience with others in writing centers, a field which claims a vested interest in working against racism in its spaces and beyond, but has failed to invite in the voices of those who experience racism, i.e. people of color. In the next part of the article, Talia presents some of the context of her experience as an undergraduate tutor at her writing center and the events leading to the writing of her manifesto. Following this section, we present the manifesto, which has been revised for the purposes of this article. We are aware that manifestos are not common in academic journal articles, but offer Talia’s piece as a demonstration of “the [rhetorical] uses of anger” which provide “spotlights . . . for growth,” particularly from the fear many feel when confronted with angry Black women (Lorde, 2007, “Uses,” 124). The fourth part of the article begins with Talisha’s initial response to the manifesto and includes a back-and-forth analysis and response between the two authors. The article closes with a call to action for those in writing centers, especially White directors. The authors offer this piece as an expression and analysis of experience and a dialogue of support, as well as a challenge to the field. We refute the idea that a diverse center is necessarily a welcoming one, and ask those who are willing to listen to Talia’s story to do so openly, and then to look both inwardly and outwardly toward change.

Some Context

In September 2017, I (Talia) was working twenty plus hours as an undergraduate tutor in the writing center at my university, a mid-sized, religiously-affiliated university in the Northeast. This was my first job, so I wanted to make a good impression and be a helping hand. I had taken on the earliest shift three days a week. I was the first to prop the door open in the morning. I was never late, and I was careful not to complain. Yet, during my time at the writing center, the appreciation and dedication that I grew to feel for tutoring, as well as the writing center itself became overshadowed by the overwhelmingly negative experiences that I continue to associate with the writing center and my time there.

The idea of the writing center feeling like ‘home’ or even a ‘safe space’ in which I was welcome became so non-existent due to everything I had been subjected to, and because of the feeling of being too afraid to speak up against both visible and invisible injustices.

As a Black woman, I was called “aggressive” by a peer and accused of “creating tension” and taking conversations “out of hand” when I stuck up for myself in debates where it seemed as though the opinions of others were welcome but not my own. I was reprimanded for being disrespectful after not saying “hello” to another co-worker, however unintentionally, all under the guise of making sure the center remained “a safe space.” I was berated for the actions of other consultants, such as playing music too loud, and accused of not taking criticism well.

It is these memories that most shape my experience at the writing center and therefore allow me to express and identify changes needed regarding race and racialized narratives and the idea of validity for minorities and minority voices which too frequently go unaddressed or are overshadowed by a disingenuous rhetoric of acceptance and inclusion. It is these memories, and my most potent memory, being patronized by my directors after being called into their office, a conversation which became so verbally abusive that I left in tears, feeling worthless, alone, and afraid.

Experiences like mine, and other negative experiences of exclusion by other Black women and people of color within these spaces, limit the accessibility of a variety of voices within the writing space, and thus make it harder for oppressive spaces and one-sided narratives to be eradicated.

My writing center environment had become so toxic that I continuously blamed myself, fearing that I was being watched and critiqued even when it seemed no one was looking. I began to exchange only pleasantries with my co-workers and speaking to my directors only when I had no other option. I did not want to draw attention to myself and felt I could not afford to be anything less than perfect in order to keep my job. It was a kind of vulnerability I had never felt.

However, it eventually became clear that I was no longer welcome at this writing center. One day, when checking my appointments, I saw that I had been removed from the schedule without notice. At that point, although it seemed I had already been let go, I decided to send in a letter of resignation that afforded me some sense of dignity and control. I had been given only one chance, while it seemed others were given more, even being promoted after also having conversations about their words or behavior with the directors.

Before my dismissal/resignation, feeling silenced, but also full of fear and anger, my manifesto, which exemplifies my experiences as a Black woman within racialized spaces, including within the writing center, was written. In this piece, I challenge the notion of silence and being silenced in a way which transcends traditional academic structure and form but which may stimulate a conversation about racism within writing centers. As Lorde writes, responses to racism do not always take the form of “theoretical discussion” (2007, “Uses,” 124). So, I offer my manifesto, in the form of a letter to myself, as a truthful expression of my experience and my anger. This is both for my own personal expression, and also to identify the parallels between what I have experienced within the writing center space and within society in general, demonstrating the change that has yet to be realized.

Silence into Language: The Manifesto

“Dream, Dream Caged Bird”

Dear Future Self,

Do you remember when you were a child, and you could fall asleep in tiny places and dream of wonderful worlds and shield yourself away from all the racism? The sexism? All the damn prejudices? What was ugly, and spiteful, the hatred, the malice. Ignorance in all its forms, behold societal norms. You had no idea it was there, we had no idea. When my mom used to say it wasn’t ok to watch the news cause of all the violence? Reverted. When you screamed and dreamed without being silenced. Those were the days.

To refresh the memory, you’d probably never forget, growing up from state to state, place to place, literally no grace ‘cause you lost all your shit all the time. All the fucking time (where’s my shit!?) Like wanderers you packed and carried and carried and drove…dove into the unknown, grasping at life, at little, at soul, the soul of a little Black girl grown, hold the phone, while I share my story, our story.

Have you ever been called a nigger? If not, you’ve dodged a bullet, one headed straight to your heart and your ego, your purpose and position. So, when that happens, if that happens how would you react? Hard “er” leave a scar, much like this story from a child’s point of view. Remember that first time when Amy G. said you couldn’t have a strawberry because you were Black, and you realized for the first time how hard life was gonna be? When you realized that the world was against you, is against you, and really you have no idea why.

You have no idea girl, but when you grow up, it’ll get worse, be worse. It was a little before this age that we learned what working 10 times harder and being 10 times faster meant. Are you faster? Do you work harder?

Do you still feel censored? Like you can’t speak your mind openly and honestly, like whatever you say will be shut down, shot down, blown out like the flame or spark that initiated the talk? Have you found that perfect audience yet? The one with the whoops and the hollers? The hell yeah’s and the Black powers?

It’s always really interesting when people look at you, poke at you, mock you, stare, and spill their guts to you when you don’t give a shit about them, their thoughts, you were once friends but that has changed. When I feel invalidated, the world goes cold, it goes black. I get angry, I get mad, and I think. I don’t care about you, not you, you but the feelings that you share the negativity that you feel. I’m not invalid and neither are my thoughts so why do you make me feel like they are? We are, it are.

How can I be me? When I get angry the world shuts me down? “Ohhh that Black girl’s angry.” How can I be sure that what I am saying matters? What if I crawl in a hole without letting them know, the people, the ex-friends, the acquaintances, those who invalidate me. Everyone’s a hypocrite, they’re all hypocrites; stop smiling in my face and acting like we’re all friends everything’s cool, safe space bullshit, co-worker I’m talking to you.

Mansplaining. Gas lighting. I remember my first time. Our first time. One first time.

As I listen when you hear him talking about Kanye, I see your face old friend, and I wonder. When I speak all you hear is…blah blah, blah and all I hear is maybe this, maybe that, maybe you’re being irrational, maybe if you look at it from this angle, maybe this maybe that. Fuck this, Fuck that. I’m learning fast, you’re not one of us, stop pretending.

You have a lot of shit to say when I say this and I say that, and when other people talk about this and that, Black this and that, Black feminist opinion and this, hip hop’s soft that, you have everything to say. Everything, but nothing. I talk about identity, about what it is like to be me, but you sign up for Black Diaspora classes and listen when other people talk, White people talk, but your friend your FUCKING FRIEND decides let’s celebrate Black History Month with coal on his face. Because that’s Black right?

Set yourself free, dream, dream caged bird. Take the spill of my words and embrace it. When I feel something it’s felt, and I will not be silenced. When my fucking cards are dealt, I’m not holding my best back and waiting for you. Waiting, waiting always waiting until there’s a time, for me to spill, for me to win, for my bingo, my eureka, my golden moment…but by then, by then you’ve won. Won the minds of many, won them. What have I won? When will I win?

It’s my fucking turn, here’s some advice. Be who you want to be, say what the fuck you’ll say, with an open mouth that won’t be filtered. Be kind and love, spread wings and fly, and trample, and stomp, and fuck shit up, and tear shit down. Hierarchies, social stigmas, prejudices, can kiss our asses, give voice to the lonely, marginalized, minority masses, take classes and internalize that shit. Educate ourselves. Believe in yourself. Set yourself free.

For the love of God, set yourself free.

Love, Talia

Language into Meaning: A Dialogue

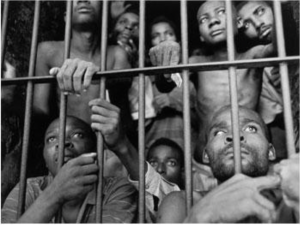

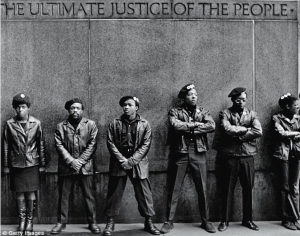

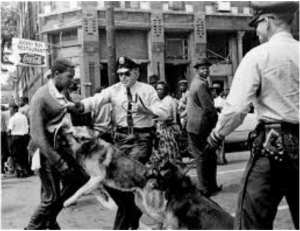

When I first read your manifesto, I was blown away by the power of it. The other thing that struck me was how naturally you connected your experiences of racism in the writing center to experiences at your institution that occurred outside of the writing center and also things you experienced earlier in life. There are also connections to broader historical and societal movements. One of the things I’ve emphasized elsewhere (Haltiwanger Morrison, 2018) is how the racism Black tutors experience in the writing center isn’t isolated from other experiences of racism. When you’re a person of color, you’re a person of color all the time, and you can compartmentalize some things, but racism is difficult and traumatizing for a lot of people. And when you’re moving across spaces, racism and other experiences move with you. And I think there is something really special, but also really difficult about being a Black woman in the United States. And very often we learn about being a Black woman from other Black women, and seeing the Angela Davis quote and the images of Black women in your manifesto, as you contemplate your own experiences as a Black American woman, was really interesting for me. I think what those in writing centers must realize is that one of the reasons we must work not to harm our students, tutors, colleagues, and others, is that we are not working with blank slates. This is not the first time you in particular or Black women in general have been made to feel unwelcome. It’s simply a new context.

I think I was able to connect my experiences in the writing center with that of historical and current societal movements, primarily because, like you said, “the racism Black people experience in the writing center isn’t isolated from other experiences of racism” and that “when you’re a person of color, you’re a person of color all the time.” It was immensely difficult going through something like what I experienced in this writing center, going in, and being told you have found a safe space, where your voice will be heard and your experiences validated, just to have the complete opposite happen, in such a stark and uncompromising way. It is heartbreaking as a person of color to realize that safe spaces so very rarely exist, and that there is still a need for caution even when those spaces might present themselves. What I have experienced at this writing center, I now will take with me for the rest of my life, to every job I have, and this will sadly more than likely never change. I will almost always feel as though I cannot trust my co-workers, or my bosses, particularly with personal or even workplace grievances. I will always feel as though I am the Black woman in the room, rather than a woman, or a person, who too can contribute ideas and allow for the growth of ideas and the sharing of a diversity of voices. Particularly as a Black woman, having this realization is uniquely more difficult, because there are all of these stigmas attached to our bodies and our existence, stigmas and stereotypes that we appear to be feeding into from the point of view of others, should we stand up for ourselves or vocalize our disdain for the inequalities we so often face. Frankly, being a Black woman, and reiterating, even in your head, the struggles that lie ahead of you, the inevitable struggles that lie ahead, sometimes, facing this sort or reality is incredibly disheartening. That is when I remember other strong, incredible Black women who have pushed the limits and have achieved what was once considered unachievable. It is in their music, their writings, listening to them speak, seeing them on my favorite TV shows and in movies, that I am lifted up and taken out of that dark place where I wonder if I can even keep going. It is in their strength that I decided to share this manifesto, even if it only started as an assignment for my English class, but became a coping mechanism for everything that has inspired it. So yes, being a Black woman is hard, but we have consistently proven that we cannot, and will not be stopped nor silenced.

As I noted earlier, one of the things that really stood out to me was the way you connected other experiences of racism with your experiences in the writing center. You told me the story of Amy G. and the strawberry during one of our previous conversations, and then it came up in your manifesto as well, how she refused to share with you because you were Black, and that was one of your earliest experiences of racism. Hearing and reading about that experience with a young White girl, in the context of your experiences later with an older White woman, I was reminded of, well, many critiques of White feminism and how it repeatedly fails Black women and other women of color. Terese Jonsson (2016) uses this term, “white feminist racism.” She defines it as “a form of racism and gendered whiteness that is specific to feminist politics and that can be understood only by recognising white feminist politics as entangled with white supremacy and histories of slavery and colonialism” (p. 52). I see that in your manifesto, with the interweaving of text and images of the past and present, but also in the experiences you shared during our talk. It seems as though your director, the White woman with whom you most often interacted failed to see 1) her own racism, and 2) the connections between forms of oppression. I remember you mentioning that she tried to bond in somewhat unusual ways with the women on staff. She said she wanted the women to feel comfortable talking to her about their birth control. I wonder if she felt that simply being women was enough to bind you together, not thinking about other forms of intersecting oppressions that some women, in this case women of color, are experiencing and that she might be contributing to. She failed to interrogate her own practices and assumptions, rooted in her Whiteness, and thus enacted the racism that, I think, she wanted to avoid (Grimm, 2011, “Retheorizing,” p. 78). There is an important lesson here because so many writing center directors are White women, and many of them are excellent directors and many of them are making sincere efforts to support their tutors of color, but if they aren’t mindful of their Whiteness and aware of the microaggressions that they are committing, then they are unaware of the unwelcoming spaces they are creating, and they are doing harm.

That experience with the strawberries was my first time being discriminated against, and I could not imagine that story not being included in the manifesto because I often think of that moment. Not because I really wanted that strawberry, or even because I had been discriminated against (for the first, but definitely not the last, time), but rather because I was so young at five years old. Including that story and Amy G. in the manifesto, alongside a range of experiences that I reflected upon that happened at the writing center allowed me to conceptualize the two in a way that encompassed the idea of a lack of safe spaces or safe ages, or the idea of innocence being stripped away, repeatedly and throughout my life. When I first started at the center, I felt like what had happened to me, could have never happened, specifically because it was almost as if my directors had set everything up perfectly, as to where that would never happen. But that in itself became so toxic and dangerous because it never allowed problems, however minor, of discrimination, or microaggressions, which were extremely pervasive in the writing center, to be evaluated and discussed in a way that helped those who were suffering under those problems. And furthermore, it created an environment where even speaking about such things in the context of the center could be considered dangerous. That is why, even though I could supposedly have spoken up about what was happening around me and what I was experiencing because I had been told up and down what a safe space the writing center was, I knew that the only safe space I had at the time, was in writing this manifesto. As for the idea of White feminism, and how it fails Black women, it reflects this framework of appearing so “open” and forward, to the point where other voices are being silenced because they become unfathomable in the space. I definitely believe that my female director, like so many White feminists, or even liberal White Americans, fail to realize their own racism and the role they have in reinforcing oppressive structures primarily because they also fail to consider how they may need to continue discussions on racism and how it exists within a variety of forms and within many, if not all, institutions, as well as realizing that those discussions cannot only be held solely amongst themselves and without real inclusivity.

So, you were called “aggressive” a few times, which is not surprising, but still worth noting because you’d think that a stereotype like that of the “Angry Black Woman” is one people who study language would be aware of and be mindful to avoid. I say “stereotype,” but the “Angry Black Woman” is really more of a controlling image (Collins, 1990), a concept with roots in the slave era that relies on negative depictions and ideas of Black women to justify their oppression (p. 7). Collins also says that, because such images of Black women have been around for so long, they come to seem for some as “natural, normal and inevitable” traits of Black women (p. 7), which perhaps explains your co-workers’ responses. As a Black woman, it was natural that you would be overly aggressive. And your directors, it seems, also took it your “aggressiveness” as natural. And then, the legitimate anger you felt after having your character attacked, you’re unable to show because as Melissa Harris-Perry (2011) notes, the controlling image of the angry or aggressive Black woman “does not acknowledge Black women’s anger as a legitimate reaction to unequal circumstances; . . . it can be deployed against African American women who dare to question their circumstances, point out inequities, or ask for help” (p. 95). I’m thinking specifically of the time you were called “aggressive” after asking for help with what eventually became your manifesto. Someone you had never spoken to, a White graduate tutor, mentioned that you were asking for help and “being really aggressive.” In your manifesto you write about how you felt pressure to perform academically, like you had to do better than your White counterparts to achieve the same things. This is what Burrows (2016), and others have referred to as the “Black tax,” the idea that Black students have to do everything better to achieve the same results. Burrows provides four themes of the “Black tax” two of which are “presenting an acceptable form of blackness” and “recognizing that the African-American subject is an intrusion to the White institution.” You, by daring to express your opinion in these institutions (the larger university and the writing center itself), presented an unacceptable form of Blackness. By asking for help, by being “aggressive” (i.e., not invisible) you did not respect your position as someone allowed into a White space, despite the inconvenience of having you there. This instance illustrates very clearly what Sherri Craig, Assistant Professor of English at West Chester University described to be as “Invited, but not Welcome,” which distinguishes between physical representation and actual participation and inclusion in a community (personal communication, 2 September 2018). You’ve been invited into the space, perhaps in the name of “diversity,” perhaps because those who’ve invited you thought they wanted you there, or thought an invitation was enough. But just because you are there doesn’t mean you can participate or contribute, doesn’t mean you are welcome to do so. Craig’s concept is an excellent reminder of what Denny (2010) tells us, which is that increasing the numbers of tutors of color is not itself enough to create change.

I absolutely agree with this. The idea of not being aggressive in the first place, and then, on top of that, having to force yourself not to get angry or even defend yourself, especially when you are in the right, and know it. This scenario was extremely difficult and something I consciously remember dealing with in the writing center. I remember after I was called “aggressive” I had to make sure that any inquiries I had about why I had been called that were asked in a “controlled” way, meaning I kept in mind my tone, attitude, and the nature of my questions that whole time. Even being sure to work in a few concocted smiles in between, so they would be comfortable, you know? It was hard, and what made it even harder was the feeling that I was extremely alone in my experiences. Chances are, and looking back now I understand, that there were probably others who had similar instances during their time at the writing center. But again, we were all vulnerable given our lack of power, as well as our financial dependency on the center itself and our jobs there. I mean, the same student who called me aggressive had a graduate assistantship, and therefore I viewed him as having more authority in the center, although not my actual boss or one of them, if that makes sense. He had their ear, and I believe he also had enough influence to get me another meeting in that office or possibly even fired. As you mentioned, it could be expected that someone in his position would know the one of the repeated or utilized stereotypes for Black women is that of being angry and hostile. I was angry, and I was the problem. This is so dangerous to Black women and especially Black women working in spaces that are portrayed as “safe spaces.” Safe for whom, is the question, and for how long? How many times do Black women have to stifle their voices, and be sure not to ruffle any feathers? This entire concept feeds into the same stereotypes that writing spaces have argued that they work to break down. I heard many times while working in the writing center conversations about breaking down the patriarchy, yet, it was this White-male co-worker who had called me aggressive, and potentially aided in my removal from the center, as well as my male director, who I very seldom spoke with, who did most of the berating during our one-sided conversation in the office. “Patriarchy” in this writing center, becomes synonymous with “hierarchy,” as it so very clearly continues to establish who has a right to say what and when, as well as who is believed, who is protected, and who is attacked and criticized, especially when my white female director helped uphold the hierarchy by standing by while I was belittled and brought to tears, which goes back to our previous point about how white women fail women of color. In my case, there was no question on whether or not they were wrong, but only how and to what extent I was wrong, and how I must be held accountable for my wrongdoings. I believe that in itself speaks to the nature of the institution.

Something that has come up repeatedly in our conversation is the idea of “validity.” You shared how your writing center often spoke about making people feel validated, that their voices were important, but you felt invalidated during your meeting with your directors, and then again when you were witnessing the conversation about hip hop. The conversation was mostly about Black male hip hop artists, but what was upsetting was that your colleague claimed to be applying a Black feminist lens for his analysis, and yet suggested male rappers shouldn’t show any emotion because that made them “soft” or feminine, so his comments were also disparaging to women, especially Black women. The conversation happened in front of you, at the same table, but you weren’t invited to participate, and didn’t think you should speak because of your previous experiences being called “aggressive.” The way you interpret that experience in your manifesto echoes the rhetorical strategies Gwendolyn Pough (2004) writes about Black women her book, Check It While I Wreck It. Pough provides an analysis of Black women’s challenges breaking into the hip hop industry and their struggles for respect and recognition, as well as how their rhetorical strategies have roots in both rhetorical traditions and larger systems of oppression against Black American women. She discusses how Black women have had to fight back against silencing efforts and societal expectations, against patriarchy, and one particular strategy they’ve used for this is channeling their anger into their art. We discussed earlier the trope of the “Angry Black Woman.” However, the anger in your manifesto is justified and appropriate. It is a response to racism. Audre Lorde (2007), in another essay, “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” says that the response to racism should be anger and is a response to anger: “Women responding to racism means women responding to anger; the anger of exclusion, of unquestioned privilege, of racial distortions, of silence, ill-use, stereotyping, defensiveness, misnaming, betrayal, and co-optation” (p. 124). This quote speaks to so much of your experience, conveyed through the manifesto, and so much of what cannot happen in a writing center if it is to be, not even a home, a place where people feel both invited and welcome (Craig), but even a place where people feel they can come and simply do their job.

The idea of Black women facing a lack of appreciation and respect in terms of our identity really is highlighted in Lorde’s words. Black women are seen as angry and hostile, yet we are not allowed to be vulnerable, show fear or weakness. Not only because the idea of vulnerability surrounding the Black woman has been deemed almost unrealistic given that we are so “loud and defensive,” but also because, truth be told, there is no one there for us to show the compassion Faison and Treviño (2017) discuss or simply to understand us when we show that kind of vulnerability, and therefore it almost becomes risky in a whole other way. When I was crying in the office while my bosses belittled me and invalidated my voice, I felt vulnerable and weak. I could not defend myself. I couldn’t explain to them how they were making me feel, and why it was so wrong. I cried, and showed that I was not only apologetic, but defenseless and scared, and the same man who wrote that piece on hip hop had been called into the office before like I had been, many times according to other co-workers and himself, yet he retained his job at the writing center (and eventually even received a graduate assistantship there), while I was not allowed.

What really upset me, beyond my colleague’s idiotic idea that hip hop becomes soft when Black men show emotion, and therefore they should not or cannot show emotion as a result, was his use of Black feminist literature, narratives, and ideas to construct his argument. Yet, he completely disregarded the position of Black women, not only in hip hop, but also in the eyes of society. As a tutor in the writing center, I felt I would not have only been ignored or invalidated had I given my opinion on the subject (I was physically ignored as I was sitting there beside him), or given him much needed facts to reconsider his theory, I would have been, like I so often was, deemed a troublemaker of some sort, or, my personal favorite, blamed for “[taking] things out of hand.” The irony of this is ridiculous. In his own words, the male tutor writing about hip hop said “…I thought I could just look up Black feminist opinion and that was it . . .”. The ability of White men, in this context, to find a way of justifying the use of the voice of the Black feminist, and twisting it to fit their agenda or within their framework of study, which by no means considers those behind the work, whom the work is about, or how they may be warping their narratives and discussions against those people, is inexcusable.

Conclusion: Silence into Action

As mentioned earlier, one of the reason’s Talia’s experience was so difficult was because she was so surprised it was happening in this setting, a writing center with so much surface-level diversity and where it seemed so unlikely that she would experience such blatant racism. What the experiences described here remind us is that representation is not enough. And yes, it is important to be mindful of the experiences of writers of color who come into our center and to do our best to make them feel “welcome,” but one of the things repeatedly mentioned as a way of doing this is increasing the number of tutors of color on staff, so that writers coming in feel more comfortable. Talia’s experiences demonstrate clearly that numbers on staff do not mean inclusion in a community or a sense of safety or welcomeness. If the tutors on staff do not feel comfortable or welcome, they will have a hard time doing their job well or making writers feel welcome. While working at her writing center, Talia spent a lot of time wondering if she was the only one having difficult experiences, but later found that she was not. It is easy, and so tempting, to say “not at my center,” especially if you have made an effort to hire a diverse staff. And hopefully, if you are an administrator, you are not bringing your tutors to tears and calling young Black women “aggressive,” but this does not mean your center is not “rife with unresolved identity politics around race” (Denny, 2010, p. 38). It does not mean that tutors of color do not feel the pressures, the unease, the unspoken Whiteness that Faison and Treviño spoke of and that makes spaces unwelcoming to them and those like them.

Talia was not just made to feel unwelcome, she was silenced, several times. However, by daring to speak again when she has been silenced, she takes action. Writing center practice is grounded in scholarship, some of it on anti-racism, which must involve action. Geller, Eodice, Condon, Carroll and Boquet (2007) inform us that “Sometimes, anti-racism work involves naming assumptions, behaviors, policies and institutional practices as racist” and that as tutors or administrators, “any of the range of strategies we might employ are meaningless unless they are framed by a grasp of the theories, philosophies, and scholarship that informed their development” (p. 94). We name the assumptions, behaviors and practices Talia endured as racist. We see the field’s focus on writers of color and silence on the very real experiences of racism faced by tutors of color in writing centers as maintaining silence, and we offer this piece to disrupt it. We also ask you to join us in this disruption, to take action with us.

Audre Lorde tells us that the response to racism should be anger, and that silence will not protect us. As Black women working in a field dominated by Whiteness and White people who may be inclined to deny the privilege of their positions due to a “lack of institutional power,” we call for an interrogation of Whiteness by White administrators and tutors. We recommend further action that is open, direct, and if need be, loud. We ask for accomplices instead of allies. We ask you to acknowledge your privilege, and be willing to give some of it up (Green, 2019, p. 29). We recommend specific actions such as implicit bias training for all staff, including tutors of color; conducting a case-study on your center’s “safe-ness”; revamping tutor training and hiring practices; creating time for informal check-ins with tutors (being open and accessible to discuss issues in the center); and drawing on the voices and experiences of tutors of color to inform the practices and scholarship of our field. And if you are a White scholar, we recommend choosing to co-author with a tutor or colleague of color, rather than offering, always, your own single perspective on matters of racism and anti-racism in writing center contexts, which limits what scholarship is available for tutors and administrators to understand the issues in the field. We ask for a “willingness to be disturbed” (Diab, Ferrel, Godbee, & Simpkins, 2013) and a commitment beyond surface-level representation. We have spoken, and we know it has been worth it. We hope you believe so, too.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank IWCA for their support of research leading to this publication.

Author Biographies

Talisha Haltiwanger Morrison is an Assistant Teaching Professor and Associate Director of the University Writing Center at the University of Notre Dame. Her research interests include writing center studies, community literacy and engagement, critical race theory, and disability studies. Talisha’s approach to writing center studies draws on critical race theory, Black feminisms, and intersectionality.

Talia O. Nanton is a senior at St. John’s University and former undergraduate writing tutor. She is pursuing a dual degree program with a B.S. in Communication Arts and an M.A. in Government & Politics with a subset in International Relations.

References

Boquet, E. H. (1999). “Our little secret: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions.” College Composition and Communications, 50(3), 463-482.

Burrows, C. D. (2016) “Writing while black: The black tax on African American graduate writers.” Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14.1 http://www.praxisuwc.com/burrows-141

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought. New York, NY: Routledge.

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP.

Diab, R., Ferrel, T., Godbee, B., & Simkins, N. (2013, August 7). Making commitments to racial justice actionable. Across the Disciplines, 10(3). Retrieved from https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/race/diabetal.pdf.

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., and Boquet, E. H. The everyday writing center: A community of Practice. University of Colorado Press.

Green, N. (2018) “Moving beyond alright: And the emotional toll of this, my life matters, too, in the writing center work. Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15-34. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26537361

Grimm, N. (1999). Good intentions: Writing center work for postmodern times. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Haltiwanger Morrison, T. M. (2018). Nooses and balancing acts: Reflections and advice on racism and antiracism from Black writing tutors at predominantly White institutions. Retrieved from Proquest Dissertations and Theses.

Harris-Perry, M. V. (2011). Sister citizen: Shame, stereotypes, and Black women in America. Hartford, CN: Yale UP.

Lorde, A. (2007). “The transformation of silence into language and action.” In A. Lorde (Ed.), Sister outsider: Essays and speeches by Audre Lorde (40-44). Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

— (2007). “The uses of anger: Women responding to racism.” In A. Lorde (Ed.), Sister outsider: Essays and speeches by Audre Lorde (124-133). Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Pough, G. (2004) Check it while I wreck it: Black womanhood, hip-hop culture, and the public sphere. Lebanon, NH: Northeastern UP.