Alex Wulff

Following Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s (2013) directive that “[n]ow is the time for peripheral visions” in writing center work, this article is about chasing after one such vision: a writing center where struggling students visit at the same rate, and then return at the same rate, as their peers (p. 88). This might not seem like a peripheral vision, as McKinney means for these visions to represent a substantial breaking and questioning of what has come before. Yet, once the writing center I was directing accepted a definition of struggling students as students who are struggling academically to the point where they were considering withdrawing from our institution, it became possible to see a different vision of what access could mean. Writing Centers are historically and pedagogically tied to questions of access, which is one reason writing center directors and tutors like to talk about centers as being “welcoming” to all writers. University administrators have long understood writing centers to be a place where struggling students can gain access to the kinds of support that will allow them to succeed at institutions that have admitted students they come to admit are underprepared. In response, writing center scholarship has, at least since Steven North’s “The Idea of the Writing Center” (1984), sought to resist the label of remediation and to replace it with what McKinney (2013) has called the “grand narrative” of writing centers: “writing centers are comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-on-one tutoring in their writing” (p. 6).

I believe this drive to make all students welcome obscured my ability to see who was missing at Saint Louis University’s writing center. In order to move towards more meaningful access, struggling students (as opposed to all students) became the focus of our training methods. What follows is a map of how I came to realize the center I was directing was failing to live up to the goals relating to access already in place when I arrived, how my first tutor training class at Saint Louis University worked to investigate the reasons for this failure, and how an advising office ended up being a key difference maker in how tutors were able to turn the center into a place that struggling students not only visited, but returned to at rates approaching their peers.

Moving a partnership with an advising office from the periphery to a central component of our approach to working with students seems like a radical step. It was not a step taken lightly, and the argument here is not that the path followed by one writing center should be followed lockstep by others. Rather, the adaptation of an advising model—Appreciative Advising—to a framework for writing center work may provide other directors and tutors with a different lens to view their own path. The similarities between Appreciative Advising and writing center practices could simply be reason for closer partnerships, or stronger referrals, given other institutional circumstances. Nevertheless, privileging struggling students in our methods and our trainings, over a welcoming approach for all students, would have been an even more difficult transition without the adaption of Appreciative Advising.

Shifting from trying to create a welcoming environment for all students, to focusing on developing tutors who are able to create meaningful bonds with struggling students was a defining moment for our center’s push to be more accessible and inclusive. That push took some time to take shape. It would be through the experience of teaching my first tutor training course at my new institution that the need to privilege what an advising office was already doing would become clear. Only after struggling to help some of my tutors-in-training process the best ways to support struggling students did I realize that the center needed to shift entirely from a training model for all students, to one that privileged struggling students.

The shifts in training that followed made our center more accessible and inclusive. We were simply not in a position to prioritize being welcoming for all at the expense of actually welcoming those who needed the most support on our campus. The parameters of and markers of being welcoming for all students can mask privilege and be limited by their cultural definitions. This does not mean that the desire to be welcoming for all and meaningfully inclusive are mutually exclusive goals. In fact, our focus on working with struggling students dramatically increased the likelihood that all students would visit and return to the center. Yet, time to train consultants is finite. A focus on being welcoming for all and a fear of being linked to remediation can work as impediments to meaningful inclusion.

We were already following the advice of theorists like Beth Boquet (1999) and Nancy Grimm (1999) to be suspicious of comfort. Grimm (1999) especially marks the ways that positioning ourselves as “fair” or “comfortable” spaces means that we are more likely to “avoid situations that produce discomfort, turning to indirect communication when situations make us uncomfortable, and inadvertently sidelining the people who make us uncomfortable” (p. 115). Tutors trained on uncomfortable conversations, yet we had not yet interrogated the ways that welcome might work to similarly exclusionary ends. In fact, I thought being “welcoming” to all students was one of our strengths, that we were moving in a positive direction. By most metrics, qualitative and quantitative, we were. We were quite literally welcoming more students to the center and more students were returning. We worked on greeting writers at the door, guiding writers to workstations, and trying to make writers feel welcomed into our space. In short, we had the kind of welcoming checklist that a lot of centers have:

- We advertised our services as available to all students

- We said we were welcoming and inclusive, and consultant training focused on student populations we knew needed additional support on our campus

- We emphasized our availability to work at any point in the writing process

- We encouraged students to come early in the writing process

- We emphasized student confidence and opposed confidence building to the simple editing of documents

- We emphasized the conversation and dialogue students could expect to have about their writing

- We thought a lot about our space, the furniture in it (round tables and couches) how students entered the space, and what they would see once they did

- We prioritized return visits and celebrated the students my tutors called their “regulars”

A large part of our identity was wrapped-up in the sense that we were welcoming. In fact, when I removed restrictions against instructors requiring students to attend our center, there was pushback from tutors. Yet, once I framed this as our need to simply be even more welcoming of writers who did not feel invited, that pushback retreated.

Additionally, the feedback I had from my tutors and the sessions I was observing made it seem like we were working with students who were struggling. We were asked to track grades before and after consultations (using mid-term and final grades in the same course) and we were certainly not just working with students with Bs trying to get As. We were working to make low performing students “welcome.” Without a clearer way to count what a struggling student looked like, I thought our work was at least moving in the right direction. Yet, I would find—hidden in a simple bar graph—that the center I was directing was not being utilized—and when utilized, not returned to—by students who were truly struggling. That bar graph was a graphic representation that our sense of being “welcoming” was a false sense of security, but that bar graph was not the first time I had ever questioned a writing center’s understanding of welcoming.

The desire to be welcoming has a long history in writing center practice and scholarship.[1] Fifteen years ago, when I began my career in writing centers as an Assistant Director, we offered to make writers tea or coffee when they first arrived. Spending 5-10 minutes talking with a student as the tutor prepared a cup of coffee was meant to be emblematic of our “welcoming” environment. Undergraduates and graduate students both like coffee and tea; the University had just spent a good deal of money to build a coffee shop not 50 yards from our center (see Figures 1 and 2). Yet, almost none of our writers accepted that free cup of coffee. Given the line at the new coffee shop, what was going on?

Simply put, that free coffee was going to cost something students did not want to pay: 5-10 minutes of the time they were hoping would be spent helping to make their piece of writing better. This made visible the tension between what we said we wanted to do for students and what students wanted us to do. We wanted them to feel a sense of welcome, even belonging—and they wanted to make their writing better. We could see the connection between the two, but writers did not see the writing center as integral to feeling “welcome” at the University.[2] Peter Carino (2003) moves this same tension inside the tutoring session by examining the conflict between non-directive and directive tutoring techniques in his seminal chapter “Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring” from The Center Will Hold. Carino draws a distinction that many centers have taken to heart: writing centers needed to know they were not “the local coffee house” while keeping the status of “safe hous[es]” (p. 109). Carino links coffee houses to purely nondirective centers, while “safe houses” combine the directive and nondirective without becoming “just another impersonal office on campus” (109). Like Carino, I thought moving our center away from non-directive methods would solve the problem symbolized by students not accepting our not-so-free gift. Yet, what if the directive and nondirective balancing act suggested by Carino does little for the students who need the most support?

Nine years later, after becoming the director at a different writing center in 2013, I found that students not accepting free coffee did not scratch the surface of students refusing what a writing center was offering. Simply put, the students who needed the most support on campus rarely set foot inside our center. Even worse, when those students did come to the center, they returned at a rate of about half of their peers. It would not be until I learned what a few of those “impersonal office[s] on campus” had to teach me about welcoming students who do not feel welcome at the university that we would be able to align our center with our goal of increasing access for students. That is, my understanding of what it meant to “welcome” someone to a writing center was blinding me to the work my center had to accomplish before we could do any real, meaningful work on inclusion. I had all the biases Carino reveals when he calls the other offices on his campus “impersonal.” I had all the biases created by watching the “welcoming” environment of multiple writing centers. We needed to shift from a focus on traditional (culturally-embedded) markers of welcome to evidence-based practices of accessibility and inclusion.

North to Carino

I did not think I was running a non-inclusive center when I began my first job as a writing center director. In my first three months, we had multiple meetings and trainings concerning directive/non-directive tutoring, anti-racism efforts in writing centers, working with international students, and a number of others that would be familiar to everyone reading this article. I emphasized the importance of being able to work with diverse student populations, as my predecessors had done prior to my arrival. There was an existing training course for undergraduates and a short training period for graduate students. The part-time staff were experienced.

Yet, when I was asked how many international students my center had served in the past year…the data had not been collected.[3] In putting out an all-points bulletin for data on student populations, I gained access to a graph depicting usage by “at-risk” students. These were students the university considered to be “at-risk” of not being retained. While I do not have access to the exact algorithm for determining these risk factors, grade point averages, standardized test scores, first generation students, Pell-grant recipients, African-American male students, students with disabilities, and students with mental health concerns featured prominently in the calculus. Only 80 students out of 350 students who were designated as “at-risk” had even visited the center in the previous year. Only 16% of that number had returned.

Every writing center is different. At a small enough institution with a long wait list for appointments, these numbers might not have been as eye opening. This was not our center. We had a staffing budget that ran into hundreds of thousands of dollars. We also had availability. Our fill-rate was hovering around 60%. We had resources. I thought a lot about that 16% return rate for struggling students. I knew we were on a path for reproducing that number because I could not even explain why it was so low.[4]

As McKinney (2013) indicates in her chapter critiquing the grand narrative that “Writing Centers are Cozy Homes,” we were trying to “construct a space different than classrooms and other impersonal spaces” (p. 22). I had not yet seen the value and connections writing centers have to these “other impersonal spaces.” Instead of looking outside the center to explain why struggling students were not returning once they came, I looked inside the center. Specifically, I looked to confirm a bias that I had about why students might not be returning to the center: I thought perhaps our practices were too nondirective, that “at-risk” students who were not returning were not getting the support and scaffolding they needed to find our services valuable.[5]

As I have often done, I tried to teach my way to an answer. I was already designing the first iteration of the writing tutor training course I would offer in the spring semester. Having taught writing center training courses as an assistant director, I was following a familiar path in designing the course, but I wanted the class to explore specific ways they thought the center could live up to the accessibility and inclusive promises already found throughout our training materials. The final project became an institutional analysis of the writing center. What promises were we making? Were we living up to those promises? Were we too nondirective?

Unlike my previous institution, I did not have students tutor until after the first half of the semester. They spent the first half of the semester observing, interviewing staff tutors, and interrogating the practices they were observing. I tried to create space for them to be critical about what they were seeing. This was no small challenge. I was asking them to learn how to be tutors, but also to be able to point to a specific moment they were seeing and talk about what a more experienced staff tutor might be missing. I opened the course with John Paul Tassoni’s “Should I Write About My Grandparents or America? Writing Center Tutors, Secrets, and Democratic Change” (1996). In Tassoni’s take on nondirective practices, support was being denied to students who most needed support. I wanted my students see how they could place access and inclusion at the core of their institutional analysis of the center.

I followed Tassoni with North’s “The Idea of the Writing Center” (1984) and “Revisiting ‘The Idea of the Writing Center’” (1994). These pieces open up a space for students to imagine the writing center as different from, and more powerful than, other educational spaces. I closed our discussion with an exercise asking my students to think through situations and student populations who would be left out by the kind of talking cure for what ails writers found in North’s piece. This is not a terribly difficult exercise after reading Tassoni, and it prepared them to read Peter Carino’s “Power and Authority and Peer Tutoring” (2003). Carino believes writing centers balance directive and nondirective methods effectively, but that they promote themselves as nondirective as a way to maintain the sense of the center as a “safe-house” (p. 109): an alternative space on campus, one where students are offered something fundamentally different than other support options.

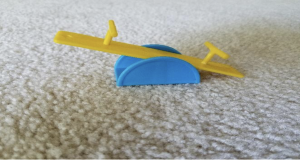

How do we know effective management of directive and nondirective methods when we see it? Carino offers a simple answer, a “sliding scale” based on knowledge: “More student knowledge, less tutor knowledge: more nondirective methods. Less student knowledge, more tutor knowledge=more directive methods” (p. 124). As my students pointed out, Carino’s scale quickly turns into a teeter totter in practice (see Figure 6), as a tutor may have less knowledge about a lab report, and more knowledge about paragraphing at another moment. So long as the tutor ensures that knowledge is being used as the fulcrum, the balance of directive and nondirective methods is being achieved. But what happens when knowledge fails to work as a fulcrum?

Teetering past Carino

What happens to Carino’s teeter totter when we add gender differences, class differences, religious difference, and ethnic differences? While Nancy Grimm’s Good Intentions: Writing Center Work for Postmodern Times (1999) came out four years prior to Carino’s “Power and Authority,” I taught Grimm’s text after Carino’s precisely because her book complicates any easy answer to that question. I was hoping that, through observations and mentoring, my students would be able to use Grimm to shed light on why struggling students were not returning to our center.

I did receive final papers that conducted an institutional analysis along those lines. These papers focused on specific student populations and moments those populations were not being supported. My students used their observations and authors like Tassoni or Grimm to call for support that was more self-aware and nuanced. I also received papers that defended North and expressionistic approaches to tutoring more generally. Like the authors in the collection Critical Expressivism: Theory and Practice in the Composition Classroom (2015), my students wanted to update the expressionist emphasis on dialogue and the writer’s “self” with increased awareness about serving different populations. Both of these strategies (pushing against the center and its current practice through Tassoni and Grimm) and buttressing the center (through an attempt to revitalize North) did make me feel that some of my concern about directive and nondirective practices was warranted.

At the same time, I was more concerned that two of my strongest students struggled to write very different papers. Both of them were writing within a fairly common trope in writing center discourse: the difficult writer. I have always struggled with this trope for the exact reason that my two students had selected their examples. While they were both writing about writers who were difficult to work with because of a lack of motivation, they both could see why their writers were so unmotivated.[6]

One of my students was working with a student who had a mental disability that made composition difficult, and the other was working with a student who felt so self-conscious about his writing that it brought his belief that he belonged at the University into question. Simply being in a composition classroom and being asked to write at the level of his peers seemed to be enough to push him towards leaving assignments for the last minute, or incomplete. He was open about his thoughts about transferring. Trying to turn lore into a small sample size, I checked and found that both students had been flagged as “at-risk” by the University’s algorithm. Both students had returned, but both cancelled frequently and my students felt overmatched in their interactions. Tellingly, neither one of my students felt that the directive and nondirective scaffolding of the course really helped them see how to better support these particular writers. It gave them techniques and options, none of which seemed to reach these writers in meaningful ways. They wanted to be able to help motivate these writers in ways that our training did not currently support. I needed to find a way to help them.

Appreciating Advisors

Discussing my students with a director of an advising office pushed something from the periphery into focus: there was an awful lot about working one-on-one with “at-risk” students I did not know because I had been working under a Carino-like premise that this was something writing centers knew how to do but just were not explaining well. While the consultants and I would end up making extensive use of writing center scholarship to inform and flesh-out the framework we created for working with these struggling students, making struggling students the focus of our training did change our methods and our practice.

My colleague ran an advising office for students with undeclared majors, and a number of his students were found in that 350 student “at-risk” grouping. We discussed advising models and their impact on student retention. He introduced me to the model our University had chosen for its new “at-risk” advising office: Appreciative Advising. As I did more research, I was hoping to find ways that writing center practitioners and theorists had been in dialogue with Appreciative Advising, or advising more generally. With only a handful of exceptions, I found what Neal Lerner documents in his 2014 article, “The Unpromising Present of Writing Center Students”: writing center scholarship cites writing center scholarship.[7] There were no substantial links being built from writing center scholarship towards academic advising. While writing center scholars and practitioners had published outstanding articles and books on specific student populations, there was not much that I could find that would help a writing tutor work with a student struggling with financial difficulties. What methods or practices should best be deployed with this distressed student? My training in a more traditional writing center gave me what I thought of as some helpful answers to that question, and I am sure that there are those of you reading this who can list approaches that might help. Yet, I could find no substantial evidence that these approaches would work.

On the contrary, Appreciative Advising came with a substantial data set, and its utilization was being tracked across a wide array of campuses featuring wildly different student populations (Hutson 2010, Bloom et al. 2010). Fully explained in The Appreciative Advising Revolution (2008), Appreciative Advising is a framework for working with students who are “at-risk” of leaving the university. It is a positive, strengths-based framework.

At first, I was not sure how we would adapt Appreciative Advising, or even if adaptation would be the right word. I did find Appreciative Advising promising because the language used to discuss the framework sounded akin to writing center work. Bloom, Hutson and He defined the framework as “the intentional collaborative practice of asking open-ended questions that help students optimize their education experiences and achieve their dreams, goals, and potential” (n.d.). While this would not be my gloss for what happens in a writing consultation, it seemed similar enough to pursue a link to writing center work.

Besides doing extensive research on Appreciative Advising and its link to retention efforts (Bloom, 2010; Tinto, 1999), I was able to include myself in the Appreciative Advising trainings paid for by my university. Bloom herself visited the campus and the trainings she facilitated emphasized the positive, strengths-based nature of the framework, which I saw as deeply applicable to what writing centers try to accomplish with their students. The framework was designed to work extensively on student confidence and motivation, and emphasized that simply “breaking the ice” with students did not count for enough of an opening engagement. I felt a twinge as I thought about all of our training materials with words “breaking the ice” as the first step of a tutoring appointment. There was also significant emphasis placed upon helping students transfer skill from one environment to another. Rather than simplifying the attempt to get skills to transfer, Bloom registered it as the difficult, messy endeavor I was familiar with and that research has supported (Anson and Moore, 2017, p. 1-6).

The academic advisors to “at-risk” students, marketed as “Academic Coaches,” were trained for an entire summer before beginning to work with this population. While I was certainly jealous of the human resource investment that went into training seven full-time professionals for three months, having access to parts of their training process, and to the advisors themselves, convinced me that an adaptation was possible. It also meant I had close-enough bonds with these colleagues that cross-training would be possible in the future.

As it turned out, I was not the only person to notice that what Bloom and others advocate for academic advisors bears a striking resemblance to writing center work. I eventually found that, in 2001, Jenna Grogan had published “The Appreciative Tutor” in the Journal of College Reading and Learning. Grogan “proposes merging [Ross] MacDonald’s Tutoring Cycle with the six phases of Appreciative Advising to create a new Appreciative Tutoring Cycle (p. 80). Grogan replaces the framework created by Bloom with eleven phases: welcome, identify, prioritize, apply, confirm, and foster independence. I was tempted to try and implement Grogan’s phases, but she only explores the possibility in her article. More importantly, in discussions with long-time staff tutors, it became clear to me that it would be far more beneficial if tutors were extensively involved in the creation of what it would mean to focus on “at-risk” students using what we saw as valuable from the appreciative advising model. We would take what we found beneficial, and use it to frame what we thought of as best practices within our center. We would also use it to challenge those practices and create new ones.

Because it was being utilized as a retention tool, I did have to wonder about having the center painted as a remedial center. Given my training, I thought that was something I needed to be concerned about. Even if we were successful at reaching out to this subset of struggling students, would there be other students who might resist coming to the center because of the stigma attached? After the fact, the solution to this problem seems so obvious that I cringe to think that I ever had these concerns. We advertised our services for all students, and we trained to work with struggling students. Almost none of our public facing documents changed. I expanded my marketing efforts to offices who had substantial contact with students identified as “at-risk” and maintained partnerships with more general offices. The problem with welcoming all students is not that a center does actually welcome all students, it is that that rhetoric of welcoming all students can mean missing the ways a center is failing to welcome the students who most need support. It can create the assumption of welcome, rather than the need to work towards meaningful inclusion and access.

The link between retention and remediation in writing center discourse meant that while this was an easy enough solution to enact at the administrative level, it was a more difficult one at the consultant level. Trained to avoid the sense that the center was a “fix-it-shop,” some of the more experienced consultants were concerned that focusing on methods for dealing with struggling students was a return to the days before North. Using the framework for Appreciative Advising actually helped here. There is nothing in Appreciative Advising that talked about a fix-it-shop or the demand for grammar instruction and feedback. Advisors are not asked to proofread assignments very often. Instead, the consultants were able to think about where error correction fit within the framework.

I do not mean to suggest that Appreciative Advising offers some kind of universal model or metaphor for all writing centers. Writing centers do not even agree on what we should call our tutors (consultants? advisors? coaches?), and I believe this is a good thing. What the center gained from Appreciative Advising was a framework for focusing on a student population we were underserving and a chance to build a training curriculum around improving that service. This did mean rejecting some of the writing center grand narrative: “writing centers are comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-on-one tutoring in their writing” (McKinney, 2013, p. 6). We had certainly problematized comfort and welcome, and (while the tutors and I certainly thought of ourselves as embarking on a kind of iconoclastic confrontation with what our writing center had been) it does cede some iconoclastic ground to say that writing centers and advising have some similarities. Most importantly, rather than being focused on being welcoming for all, we were focused on working with struggling writers. We still used writing center scholarship to guide the ways in which we fleshed out the Appreciative Advising framework and adapted it to writing center work.

For instance, we used the work of Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Thompson (2013) to tailor Appreciative Consulting to the needs and techniques of writing consultants. The importance of communal goal setting for getting students to “work at the appropriate level of challenge” (p. 43) is built into each stage of Appreciative Consulting. Linking cognitive and motivational scaffolding addresses the readiness of the student and “pairs it with the consultant’s ability to listen, paraphrase the student, list alternatives and guide novice writers to arrive at their own solutions to problems” (40).[8]

The impact was also wide-ranging. Because Appreciative Advising emphasizes the counterintuitive nature of really being strengths-based and positive with students, the consultants and I developed a paid mentorship and observation program that emphasized ways of counting and measuring positivity and an emphasis upon building bridges between student strengths. Trainings were created on reading methods that would allow for tutors to avoid emphasizing errors if asked to read a student’s paper aloud. The new observation and mentoring programs had found that we often stopped reading to address errors as they arose, rather than prioritizing those errors. In reflective documents tutors discussed how they prioritized errors, but that was not what they saw when they observed each other with an eye towards being strengths-based and positive. When students read their own papers, this was easier to manage, but when this was not possible, errors controlled the direction of the session rather than the tutor. As a result, tutors trained on reading texts without emphasizing error and then going back after having prioritized errors that needed addressing.

The results of our efforts were dramatic, and they were dramatic for all students. Over the next three years, visits went up from nearly 4,000 to more than 7,000. The in-year return rate for all students climbed from 29% to 50%. Students the university had identified as “at-risk” of leaving had an in-year return rate of 49% by year three, a dramatic improvement from the initial mark of 16%. Notably, we did not achieve our goal of having writers the university labeled “at-risk” return at the same rates as their peers.

Using the expertise of advisors who work with “at-risk” students did not mean giving up on the lessons from someone like Carino. Carino continued to be featured in the training course, and was often written about in consultant reflections. It also did not mean promoting the writing center as a place of remediation, at least not in the ways writing centers have traditionally figured remediation. The center was even still advertised as a service for all students. It did mean that there was a stark difference in how tutors trained in comparison to our marketing. Tutor training focused almost exclusively on working with struggling students. This meant paying more attention to student motivation and strengths, and looking at ways to make directive and nondirective feedback the right balance of supportive and challenging. Balancing directive and nondirective methodologies needs to remain an important aspect of any writing center, but getting students to return who are struggling is, I believe, a defining element of a writing center that is working towards meaningful inclusion

To close, I would like to propose a basic and clear standard for measuring meaningful inclusion: unless students we can clearly identify as struggling are utilizing, and returning to, writing centers as often as their peers, we have failed to live up to the goals for increasing access set for our field by scholars like Nancy Grimm, Beth Boquet, and Jackie Grutsch McKinney. We will have allowed our sense that our spaces are “welcoming to all” to exclude the students who most need support on our campuses. This does not mean that if we achieve this goal we have achieved an adequate measure of inclusion. Writing centers can do more than just get struggling students to return as often as their peers. One way to think about the history of writing centers is as an expansion of what it means to be accessible and inclusive. For instance, getting struggling students to return is not going to achieve the goals outlined in Albert Deciccio’s (2012) “Can the Writing Center Reverse the New Racism?”: “Writing center workers are agents of change whose practices might reverse the resegregation and new racism occurring in our country” (Deciccio, para. 1). I would simply add that if we are not getting struggling students to return at the same rates as their peers, we have even further to go in being change agents than we already believe.

I realize that this is a complicated standard to put forth. The definition of a struggling student is not one that I imagine even a majority of centers could agree upon. Even the definition promoted here, a student struggling to the point of nearing withdrawal from the university, would vary from institution to institution. Institutional context matters, and comparisons across institutions would be difficult. The same demographics at a different institution would fail to translate as struggling. It was only because of preexisting analytic data about which students were most likely to withdraw from the University that I was able to get a sense of which students were really struggling. Producing such data without institutional support would be nearly impossible, but I believe generating that support is effort well spent.

Author Biography

Alex Wulff is an Assistant Professor and the Director of Writing and Multimodal Composition at Maryville University. He teaches writing and rhetoric courses with an emphasis upon writing across the disciplines. His research interests are in writing center scholarship, composition studies, and the long nineteenth century.

References

Anson, C., & Moore, J. (Eds.). (2017). Critical transfer: Writing and the question of transfer. Fort Collins, CO: The University Press of Colorado.

Beagle, D. (2012). The emergent information commons: philosophy, models, and 21st century learning paradigms. Journal of Library Administration 52(6-7), 518-537.

Boquet, E. (2002). Noise from the writing center. Logan: Utah State UP.

Boquet, E. (1999). ‘Our little secret’: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication 50(3), 463-482.

Bloom, J. L., Hutson, B. L., & He, Y. (2008). The appreciative advising revolution. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Bloom, J. L., Hutson, B. L., & He, Y. (n.d.). “Appreciative advising.” Retrieved from http://www.appreciativeadvising.net/what-is-appreciative-advising.html.

Bruffee, K. (1984). Collaborative learning and the conversation of mankind. College English 46(7), 433-46.

Carino, P. (2003). Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring. In J.A. Kinkead, & M.A. Pemberton (Eds), The Center Will Hold (pp.96-113). Logan: Utah State UP.

DeCiccio, A. (2012). Can the Writing Center Reverse the New Racism? New England Journal of Higher Education.

Hutson, B. L. (2010). The impact of an appreciative advising-based university studies course on college student first-year experience. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 2(1), 4.

Grimm, N. (1999). Good intentions: Writing center work for postmodern times. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Grogan, J. (2011). The Appreciative Tutor. Journal of College Reading & Learning, 42(1), 80-88.

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2013). Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring. Writing Center Journal, 33(1), 38–73.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan: Utah State UP.

North, S. (1984). The idea of the writing center. College English 46(5), 433-46.

Oweidat, L. & McDermott L. (2017). Neither Brave nor Safe: Interventions in Empathy for Tutor Training. The Peer Review 1(2).

Lerner, N. (2014). The unpromising present of writing center studies: author and citation patterns in the writing center journal, 1980 to 2009. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 67-102.

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions… Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?. Writing Center Journal, 37(1/2), 147-171.

Solberg, J. (2011). Becoming learning commons partners: working towards a shared vision and practice. Journal of Organizational Transformation & Social Change 8(3), 243-260.

Tassoni, J. P. (1996). Should I Write about My Grandparents or America? Writing Center Tutors, Secrets, and Democratic Change. Journal of Teaching Writing, 15(2), 195–209.

Tinto, V. (1999). Taking Retention Seriously: Rethinking the First Year of College. NACADA Journal, 19(2), 5–9.

- The emphasis upon space in writing center scholarship is emblematic of this desire to be welcoming. Beth Boquet’s “A History of Writing Centers, Pre- to Post-Open Admissions” (1999) links the argument for space with arguments for professional validation. In this sense, Writing Centers striving to be “welcoming” spaces really begins with the resurgence of writing center scholarship in the late 1970’s: Kenneth Bruffee’s “The Brooklyn Plan: Attaining Intellectual Growth through Peer-Group Tutoring” (1978) can work as a rough point of beginning that is codified in Stephen North’s “The Idea of the Writing Center” (1984). ↑

- This is empirically true and common sense. Writing support is not going to help you feel like you belong in the same way a residential learning community might. It is hard to find examples where more than one third of a university population is utilizing a writing center. The National Survey for Student Engagement (NSSE) and National Census of Writing (NCW) can both be used to mark college student’s significant resistance to being tutored in general. Writing centers are sites of belonging for only a small percentage of university students. ↑

- This is not a reflection on previous directors. There had been a gap in staffing the position of director. ↑

- The number would rise slightly to 21% at the end of that year. ↑

- In some ways, I was looking to do something akin to what Lori Salem accomplishes in her 2016 article “Decision…Decisions: Who Chooses to Use the Writing Center?” Salem points out that “It is a peculiar feature of writing center research that there has been no meaningful investigation of the decision not to come to the writing center” (p. 151) and then goes on to look at correlations between demographic data and usage. I do not have access to the formula used to label students “at-risk,” where Salem goes to some length to establish the relationship between markers of privilege and utilization. Interestingly, Salem’s data from her center’s utilization was what I imagined that I would find at mine: that struggling students were using the center more than other students. Yet, the data I obtained about “at-risk” students was focused on students “at-risk” of withdrawing from the University, rather than markers that tend to be associated with privilege. While I echo Salem’s critique that trying to serve all students, and fearing the label remedial can mean not supporting students who need the most support, I came to disagree with her conclusion that non-directive methodologies are one of the primary reasons struggling students do not return. I think writing centers have done more to move on from allowing nondirective methodologies to dominate than Salem allows. ↑

- All too often—in training videos, in handbooks, and in published articles—we allow the story of a difficult writer to sit unchallenged. Stopping at difficult means that we have left the writer’s story untold, and only responded with the tutor’s experience of being inconvenienced. Sometimes we never get the writer’s story and sometimes writers do far more damage than inconveniencing the tutor. I do not mean to suggest that strategies for working with writers who create difficult circumstances for tutors are uncalled for. Yet, it may be that the rate at which our centers churn out stories about “difficult” writers is a good measure for how our sense of having sufficiently “welcomed” a writer into the center has distorted our ability to support that writer. Welcome may be working to unjustly delegitimize the difficulties of the writer. If we have welcomed a writer, then to be repaid for that welcome with difficult behavior may put tutors in a position to misunderstand, or unfairly judge, that behavior. ↑

- “Writing Centers and Academic Advising: Towards a Synergistic Partnership,” by Brenton Faber and Catherine Avadikian (2002) is a significant exception. Faber and Avadikian actually advocate for housing writing centers and advising offices together in order to achieve a synergy between the services, but also a renewed respect within the University for both. I am not suggesting anything more drastic than the sharing of ideas and methodologies between the two services and noting the oddness of the two not being more closely integrated on the scholarly level. While writing centers usually do a lot of work one-on-one with students, as do advising offices, it is revealing that more has been written about libraries, learning commons, and success centers than about advising and potential synergy between writing center work and advising. For instance, scholarship on learning commons (Harris and Collins, 2010; Beagle, 2012; Solberg, 2011) and success centers (Robbins, S., Allen, J., Casillas, A. et al, 2009) has been mounting recently. Space is important, but asserting the unique ability of writing centers to be welcoming will, I believe, do little to protect that space while hindering avenues for growth. ↑

- In addition to addressing confidence and motivation, the Appreciative Model pressed consultants to be deeply empathetic to the hurdles struggling students would need to overcome to remain at the University. In some measure, the trainings we produced followed Lana Oweidat and Lydia McDermott’s (2017) admonishment that “As writing center administrators, we need to attend to the professional and epistemological development of tutors by teaching them to be intentionally empathetic and critically aware” (para. 7). ↑