Faith Thompson, Salisbury University

Abstract

In this embedded case study of a mid-Atlantic writing center, I interviewed and observed 3 writing center tutors regarding their academic language ideologies and conceptualizations of academic writing. I found that tutors focused on “grammar” when discussing academic language, and tutored in adherence with “rules” they expected professors to enforce. This demonstrated that tutors may hold a standard language ideology regarding academic writing. However, tutors also focused on student voice through style and word choice, and were concerned with overriding student voice through their tutoring practices. Because of these two conceptualizations of professor focused rules and student centered voice, tutors shifted between prioritizing the two in their tutoring sessions. Ultimately, I argue that tutors need to reimagine what it means to “sound academic” for a more linguistically just tutoring praxis.

Keywords: Academic language, academic writing, writing center tutors, language ideology

Introduction

In recent years, scholarship regarding linguistic justice in writing centers has increased, including:

- Tucker & Bouza’s 2024 The Peer Review special issue on linguistic justice;

- Edited collections such as Haltiwanger-Morrison & Evans-Garriot (2023), Lee, Johnson, & Fahim (2022);

- Dissertations and theses such as Blazer (2016), Krishnamuthy (2022), and Montgomery (2024), Presswood (2022), Toney (2020);

- And emerging articles on intersections between AI and linguistic justice (e.g. Fernandez & McIntyre, 2025; Lindberg, 2025; Nee, et. al., 2022; Park, 2023; Thompson & Hatch Pokrel, 2025).

It is clear that this is a pressing call in writing center studies, and for good reason, too. As Pawlowski (2024) argues, writing center tutors can uniquely “speak to how language, power, and identity are intertwined in the act of writing,” due to their institutional positioning. Tutors, who exist somewhere in-between student writers and their instructors, and the writing centers they work at, operate in liminal spaces (Shelton & Howson, 2014; Sunstein, 1998). Historically, writing centers have been seen by universities as sites of remediation for marginalized students (Lerner, 2009; North, 1994) and a place for academic writers the university may deem underprepared (Salem, 2014). Although writing centers certainly exist for all students, they often serve the marginalized students that linguistic justice most significantly impacts: international students (Thonus, 2001), first generation students (Towle, 2024), working class students (Denny, et. al., 2018), and second language writers (Garcia, 2017) among others. This means that writing centers and their tutors are poised to either maintain and support institutional goals and missions or to disrupt the oppressive and hierarchical practices, such as hegemonic language expectations, within such institutions (Basta & Smith, 2022; Newman & Gonzales, 2017; Sabatino, 2023; Salem, 2014).

However, much of the existing empirical scholarship on linguistic justice in writing center studies is either produced by administrators of writing centers and/or offers practical pedagogical insights for administrators as well as content to cover in tutor education. Little research exists on writing center tutors themselves and extant literature does not necessarily reflect the realities of writing center tutors.[1] This is a significant gap, as it is tutors who are often tasked with enacting linguistic justice in their daily tutoring sessions. The research that does focus on tutors indicates that tutors are negotiating their own past experiences, goals, and choices in relation to writing centers’ stances on language policy (Montgomery, 2024) and that they feel limited in their capacity to create change due to student and professor expectations as well as a lack of pedagogical training (Krishnamuthy, 2022). Recent work looking at the experiences of tutors of color further complicates the issue. For example, Faison (2018) demonstrates that Black writing center tutors may welcome the idea of using Black English in a tutoring session, but ultimately fear that other tutors and tutoring clients may not see them as professional if they do so. Ray & Goldin (2025) reveal that some tutors of color might also identify standardized English as their primary linguistic code, and so asking them to pursue linguistically equitable tutoring practices may require them to negotiate their own identity in complex ways. Ultimately, writing center administrators seeking to transform tutoring praxis at their centers need a clearer understanding of tutor perspectives.

Using data from my dissertation pilot project[2], I hope to provide writing center administrators with insight into the way writing center tutors approach the concepts of academic writing and language in their tutoring sessions. My data provides insight into the language ideologies tutors may hold as they approach working with student writers on academic writing.

Academic Writing and Language

I chose to focus on academic writing specifically because it is the bread and butter of tutoring work, as tutors support students daily with their writing for academic purposes. I did not provide participants with a definition of academic writing for this research.

In the literature, academic writing is often associated with concepts of standardized English (MacSwan, 2020), also referred to as white mainstream English (Baker-Bell, 2020), due to its close associations with white, middle-class linguistic practices (Greenfield, 2011). In this article, I will refer to standardized English as white mainstream English (WME) because standardized English is a mythological concept (Greenfield, 2011).

Academic writing uses language “that is assumed to be functional for the purposes of learning, knowledge construction, and education” (Heller & Morek, 2015, p. 175). Although often conflated with WME in the US, any dialect of English can be used for these purposes. Despite this, many of the marginalized students that the writing center serves are perceived as lacking academic writing skills. This is perhaps because the idea of academic language is arguably a linguistically racist ideology (Flores, 2020). If WME is assumed to be the language of academia, only those who write in WME are perceived as already academic. Not only does this normalize whiteness in academia, but it precludes students of color and speakers of racialized varieties of English such as African American Vernacular from being perceived as academic.

How writing center tutors perceive of academic writing and language could be indicative of the language ideologies they hold, which shape their approaches to working with linguistically marginalized students. Code-switching is a popular pedagogy that encourages linguistically marginalized students to assimilate their academic and in-school writing to the expectations and standards of WME. Tutors who associate academic writing with WME may encourage code-switching in their tutoring sessions over the more linguistically just pedagogies of code-meshing and translanguaging. After all, as Brooks-Gillies (2018) states, writing center tutors “frequently…embrace mainstream notions of ‘good writing’ and ‘proper grammar’ [that] often reinforce…the notion of ‘Standard English’”.

Research questions

In order to support writing center administrators in understanding tutors’ perspectives and realities in regards to linguistic justice efforts, I studied how writing center tutors approached academic writing and language in their tutoring sessions. My goal was to provide insight into the tutors’ own language ideologies. The research questions that guided my efforts were as follows:

- In what ways do writing center tutors conceptualize academic writing and language?

- How do these conceptualizations shape their tutoring practices?

Methods

This pilot project was designed as a case study of one writing center and its tutors. It took place at a medium-sized writing center at a small, public university in the mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. Although case studies are limited in that they are not generalizable, insight can still be gathered from them regarding the possible perspectives of writing center tutors due to their in-depth and more complete exploration of real world phenomenon (Rifenberg, 2020).

Positionality

At the time of writing, I am a white, lower-middle-class, college-educated woman. I am a monolingual speaker of English, and my own languaging is often perceived as WME. This perception gives me academic privilege, and this privilege, alongside my whiteness, inevitably limits my perspective. However, in my work, I seek to promote the enactment of linguistic justice in writing center studies and beyond, and am continually challenging my own language ideologies. I believe that academic writing and language is not exclusive to WME, and that anyone engaged in academic writing is using academic language, and is, therefore, academic.

I identify as a writing center researcher and tutor myself. I tutor alongside the participating tutors in this pilot project, however, I am a remote student and so I do not engage with them regularly in the workplace. As such, I occupy both insider and outsider positions within this study. I understand the realities of writing center tutors, especially at this particular writing center, but I did not begin this study with relationships with the participants. Data was collected across one semester.

Data

I triangulated the data in this pilot project by collecting three forms of data: a literacy autobiography, two interviews, and two tutoring session observations. Interviews took place pre- and post-observation in order to member-check what I was observing. As a remote student, all data was collected remotely via Zoom and WCOnline.

Literary Autobiographies

Participating tutors were asked to write literacy autobiographies at the beginning of the data collection period. Canagarajah (2020) defines a literacy autobiography as a “personal narrative reflecting on how one’s experiences of spoken and written words have contributed to their ongoing relationship with language and literacy” (p. 0). Literacy autobiographies are commonly used to study language ideologies, as they reveal one’s past experiences, goals, and choices regarding language and literacy. The literacy autobiographies were collected first to allow participants to contextualize for themselves, as well as for me, how they came to think what they think about academic writing and language. The prompt for the literacy autobiography can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Literacy Autobiography Prompt

Reflect upon 2-3 key moments in your literacy and language use journeys that significantly shaped your attitude towards academic writing. Explore in-depth one positive memory, and one negative memory, noting the impact of both. If you do not have negative memories, instead reflect upon why that might be so. You might choose to reflect on your family and educational experiences as well. You may represent these moments in any format that you feel is best: a traditional written response of 2-4 paragraphs, a multimodal slide, an audio or video recording, etc. Use these questions as a launching point for your reflections:

|

Interviews

After completing the literacy autobiography, I conducted interviews with each participant regarding what they had written and to gauge their conceptualizations of academic writing and language. These interviews lasted 30-60 minutes each. Some interview questions included:

- What is good writing to you?

- Is there such a thing as bad writing?

- What is academic writing?

- How does your understanding of academic writing inform what you do at the writing center?

- How do you help your clients develop their academic writing?

- What would you do if a client brought in writing that differed from your idea of academic writing?

At the end of the data collection period, I conducted a second round of interviews with participants to ask questions about what I had observed in their tutoring sessions to ensure I understood the thinking behind their approaches to tutoring academic writing and language. These interview protocols varied significantly based on what was observed.

Observations

I observed two tutoring sessions with each participant. Due to time constraints, I did not control for the focus of sessions nor the clients they worked with, so I was limited in my ability to observe tutors’ engagement with racially, linguistically, and culturally diverse student writers. All observations were collected within one month of each other, about 3 months into the Spring semester allowing for participants to develop some experience and comfortability with weekly tutoring. I also did not always observe tutors addressing academic language specifically, as some session focuses, such as brainstorming, did not lend themselves to working on lower-order issues. Additionally, some sessions observed were focused only on editing citations, which also had limited capacity for insights regarding the language ideologies of writing center tutors. As such, a limitation of this study is that the primary data sources discussed are the interviews and literacy autobiography.

Analysis

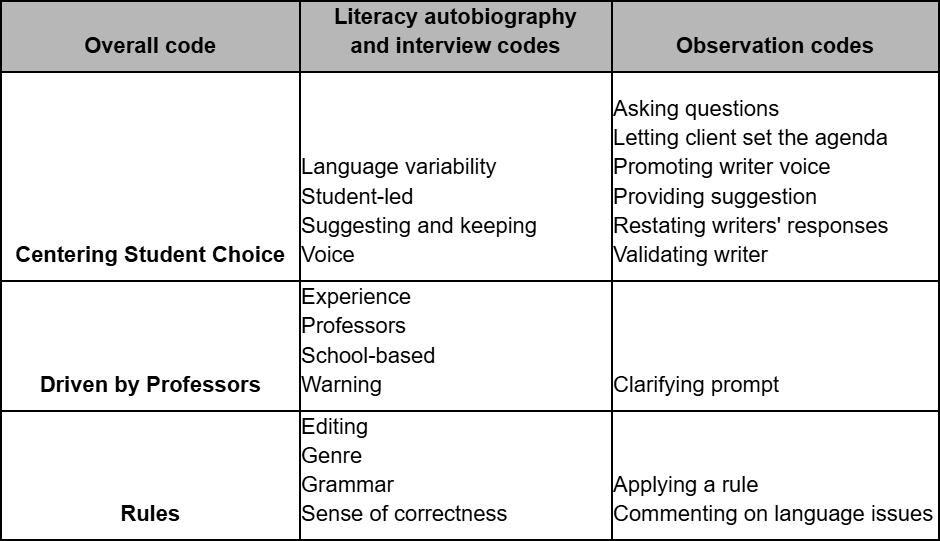

I used a two-cycle coding process for analyzing the data I collected. First, I inductively created a codebook for the literacy autobiographies and interviews. I created a second codebook for the observations, as I wanted to target the second research question with the observations, and this allowed me to code in a way that better captured the actual actions tutors took in writing center sessions. I refined these codebooks in second cycle coding and created a third codebook which connected the conceptualizations of academic writing and language gathered from the literacy autobiographies and interviews with the actions taken in tutoring sessions. That codebook is below.

Figure 2

2nd cycle codebook

From this codebook, I looked for patterns and themes, and then went back through the transcripts to find examples of these patterns and themes before determining my final findings.

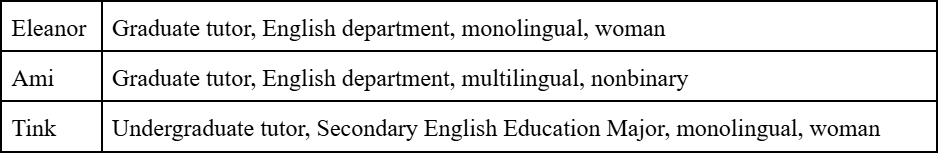

Participants

I had 3 participating tutors in this pilot project: Eleanor, Ami, and Tink.[3] All three tutors identified as white and English-speaking. All three tutors were selected because they were in their first semester as writing center tutors, having just completed their tutor education course the previous semester. The tutor education course covered linguistic justice across two class meetings, focusing on the key concepts of working with multilingual writers, using inclusive language, and challenging WME in academic writing. This brief education allowed tutors to have an understanding of what language ideologies are and a vocabulary for expressing their beliefs regarding language use in academia, which made the selection of these tutors reasonable for answering my research question. More information about each participant can be found in Fig. 3.

Figure 3

Characteristics of participants

Findings

The participating tutors in this study held similar conceptualizations of academic language, and they used common tutoring practices towards these conceptualizations across the observations. Several key findings emerged:

- references to academic language focused largely on what tutors named as “grammar”, resulting in rules-based tutoring wherein ideas of what professors expected determined the rules;

- tutors also conceptualized of academic language through voice, including style and word choice, and were concerned about overriding students’ voices in their tutoring practices; and

- tutors negotiated between their ideas of those professor-focused rules and student-focused conceptualizations of voice in their tutoring which led to them shifting back and forth between prioritizing the two.

“I’m not sure why that’s the rule, but it is the rule.”

References to language-based tutoring (sentence-level or “lower order” issues) focused largely on grammar in the interviews and literacy autobiographies. Tutors discussed grammar as providing “structure” and “basic guidelines” (Ami), but did not explicitly explain what grammar is to them. Both Tink and Ami identified what they believe grammar is as the key component to making academic writing understandable, with Tink stating “the most important thing about writing is that it needs to be understandable, and so, typically, I think grammar is associated with that, making it understandable,” and Ami explaining “grammar…makes it easier for a paper to be understood…if I’m reaching these guidelines, it should be easier for my point to be understood.” Ami nuanced this statement on grammar for understandability, adding “I feel like grammar is a good guideline but I don’t think it has to be perfectly met in order for something to be understood.”

Grammar, or at least “correct” grammar, seemed to be only associated with WME for the tutors. Eleanor noted that when she recognizes patterns of error in her clients’ writing, she tells them, “this is the thing that is part of the English grammar traditional structure.” The use of the word “traditional” implies an association with WME grammar. Tink was more explicit. She named writing in African American Vernacular English as not using “proper, grammatically correct English” but also conceded, “just because it’s not necessarily grammatically correct doesn’t mean it’s not good writing.” Ami did not believe they associated grammar with WME, but also mused, “it could be that that standard English is just so normal to me that I do it without thinking about it.”

When tutoring towards grammar, the tutors all either gave students “rules” to follow or discussed doing so in interviews. While they prided themselves on offering suggestions to students in their tutoring in general, when it came to grammar, they made corrections, presenting their language-level editing as the only correct way to write something. Ami explained doing this by stating, “we get taught rules when we write. I think it’s just some of those rules are kind of ingrained in me still…even now, I will be like you shouldn’t do it like that.” Interestingly, tutors applied rules to student writing even when they couldn’t articulate a strong reason why the rule was what it was. Eleanor told one of the student writers she worked with “how crazy all these rules are” and that “there’s a whole bunch of rules, and…honestly, I don’t even know them all, but I will try.” Meanwhile, Tink told a client “I’m not sure why that’s the rule, but it is the rule. It’s very weird.”

Tutors enacted non-grammar-based rules in their tutoring as well. In particular, the use of “I” in academic writing was discussed by Eleanor and Tink. For example, in one of Tink’s sessions, she attempted to teach the student not to use “I” in academic writing, but the student reported the professor had okayed it. Tink replied, “whatever the professor wants.” “Whatever the professor wants” seemed to be a guiding determinant in the application of rules in participants’ tutoring sessions, as the tutors imagined professors to be the ones making the rules. This is perhaps because tutors learned the rules they applied in their own education. Eleanor and Tink both mentioned college classes they’d taken on grammar that informed their ideas on “what does it mean to have a grammatical academic essay” (Tink). Tink explained how these ideas informed her tutoring, stating:

I use my knowledge of academic writing from high school and college to kind of base my advice on because that’s what professors are looking for. Like they want this academic writing in here. So I use that knowledge I have of it to help guide students more towards that because, typically, that’s what the prompts are asking for.

Here, Tink suggests that since it is professors and educators who define and expect these rules, she tutors her student writers on these rules in order to help them succeed with their own schooling. In particular, the tutors believed in teaching grammatical rules to student writers in order to prepare them for the expectations they perceived professors to hold. For example, Tink addressed that if a student writer brought in work that was in African American Vernacular English, or another nonstandardized English she believes to be grammatically incorrect, she would:

just have a conversation, be like, hey, I am just a little concerned that because this isn’t what [professors] typically ask for, and not that that’s bad, but you may not get the best grade. I would also say this is just my opinion, though, I could be wrong, and I would just leave it up to them how they would proceed, if they want to continue writing like this or if they’d like to change it to fit the normal.

It was also noted that student writers also perceive professors as making the rules, with Eleanor noting that many students come into the writing center asking “Is this good enough for my professor?” but that she tells them “I can’t tell you that, because I’m not your professor.”

Ami and Eleanor had slightly more complicated positions regarding their understanding of what professors expect as they both teach sections of first year composition themselves. While Ami said they did not focus on grammatical issues in their own sections, “other professors are stricter and…what college is going to expect of you is going to be different. So it’s trying to set them up for that too is kind of difficult.” Both Ami and Eleanor indicated they felt relief as tutors rather than teachers because there was less pressure to teach students correct grammar. However, in observations, they still taught students “correct” grammar despite the lack of pressure.

Ultimately, throughout the data, tutors consistently saw academic language as rules-based, particularly aligning to WME grammatical standards. When conceptualizing of academic language in this way, tutoring actions were professor focused, as professors were perceived of as having the power to make the rules.

“Voice is the X-factor”

Tutors also viewed academic language through a student focused lens of “voice”. All three tutors believed voice to be an important part of good academic writing, with Eleanor saying “voice is… the X-factor that makes writing good”, Ami stating “voice is what kind of gives your writing personality at all…voice is something that should be…present in everybody’s work”, and Tink explaining “good writing is when you take your style into consideration.” However, tutors struggled to define voice, with Eleanor saying “I don’t know. I read a lot of papers…and definitely you can hear the students more or less.” Although tutors were not able to concretely define voice, they did repeatedly mention style features and word choice as related to it. For stylistic features, tutors did not define style either but implied it was in reference to nonstandardized language practices and grammar. Tutors expressed that voice is what makes student writers’ writing unique even when following the rules they perceived professors to hold for academic language discussed above. Tink described this as “even though there’s kind of a blueprint for what you should expect in each writing, I think that the way you can accomplish it is different.”

Tutors’ conceptualizations of voice through academic language is at the opposite end of the spectrum from their previous rules-based conceptualizations-that is, when tutors talked about voice or were observed centering voice in their tutoring, they valued “creativity” and “freedom” (Eleanor) as opposed to rules that had to be followed. Voice, then, puts the “power” (Eleanor) in student writers’ hands rather than the professors’. There were, however, limitations to this power. For example, Tink stated “you develop a style, but you also have to really understand it to know how to work with it and actually make it productive.” Here, Tink is establishing that simply having a voice isn’t necessarily what makes the writing good, but knowing how to use voice effectively is what enhances the writing. Eleanor similarly stated “We obviously can’t be just voice. You have to have content and you have to achieve the goals that you want to achieve.” Ami put this more clearly, explaining “I kind of like trying to keep any type of style I see in writing, as long as it’s not breaking flow or as long as it’s not like hurting the paper in some sense.”

Tutors often tried to highlight and encourage student voice in their observed tutoring sessions. For example, when a writer used the casual phrase “it’s a top recipe for” to describe something, Eleanor stated to the writer, “I like this phrase. It shows voice.”

In the interviews, tutors reported being intentional about not letting their own voice “overstep” the student writer’s voice (Ami). This was something all three tutors spoke about in depth. For Tink, she said:

I never went across the boundary where this is becoming mine because that makes me feel icky, not even because of plagiarism and other stuff but just like this is their writing. And it’s their work. And I want it to be theirs…I don’t want my random style to kind of come through.

Eleanor similarly expressed that she wants writers to know “they have freedom, they have voice, they control their writing,” and doing anything to jeopardize the student’s voice is not “in any way ethical”.

Participating tutors conceptualized of academic language as allowing for student voice, and therefore student control of their writing, at least to an extent. Here, they provided more choice through suggestions for students rather than giving one “correct” rule and helping writers adhere to it.

“We have to try to negotiate it together”

Because tutors’ conceptualizations of voice and rules in academic language are in opposition to each other, tutors found themselves negotiating both academic language itself and how to tutor towards it. In particular, they tried to navigate a professor focused conceptualization of academic language and a student focused one. Tink noted that she has to “try to balance what the student wants and what the professor is asking.” Eleanor also said “we have to try to negotiate it together, like what do you want done and what does your professor want?” These quotes speak to the tension over who has authority over academic language: students through their use of voice or professors through their expectations of rules? Ami also struggled with this tension, noting:

how we direct our voice is interesting. I’ve had students…who write well, and they have this really strong sense of voice, but they really struggle with fitting genre. So that’s kind of been the struggle of like okay, how do we direct your voice to still fit the genre expectations of a paper, because that’s also just as important.

Since tutors were negotiating the tension between rules and voice, and authority over language, their actual tutoring practices or actions taken towards tutoring academic language were not consistent. Tutors did not tutor towards rules and voice simultaneously. At times, tutors either focused on rules, giving corrections, implying only one choice for student writers to make. However, they also put such weight on maintaining student voice that they sometimes overlooked student errors. For example, Tink was working with a student writer who had a sentence in present tense when the rest of the paper was in past tense. At first, Tink ignored this change, but when the student brought it to their attention, instead of suggesting the student writer sustain past tense, she said “honestly, whatever sounds right to you.” Here, her refusal to let her own voice override student choice resulted in her choosing student voice rather than upholding a “rule”.

Tutors found themselves negotiating academic language through two lenses: professor focused rules, with one correct way of thinking, and student centered voice through word choice and nonstandard style. These negotiations led to conflicted decisions in their tutoring as they shifted between the two conceptualizations.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate how writing center tutors conceptualize of academic language and how those conceptualizations shaped their tutoring practice. Ultimately, participating tutors conceptualize of academic language through two opposing ideas: their expectations of professor focused rules and their desire to preserve student centered voice. This binary shaped their tutoring, resulting in variances in their tutoring actions. Tutors’ discussion around rules reveals that they normalized WME as more correct than other diverse English languaging practices and a power struggle over control of student’s academic writing. While this conflict is significant, I argue that reimagining a more linguistically just “academic voice” in academic writing may allow writing center tutors to work more cohesively towards professor expectations and student centered writing.

Standard Language Ideology

Tutors described rules-based academic language using words such as “traditional” (Eleanor), “correct” (Tink), and “professional’ (Ami). This indicates that tutors may hold a standardized language ideology that privileges WME grammar. Interestingly, however, tutors were vague in their definitions of key concepts such as grammar and professors’ expectations regarding it. This may be because, as Reaser, et. al., (2016) puts it, WME has no clear definition, but “speakers of English know when they hear it,” (p. 17). Ami echoes this when he stated “standard English[4] is just so normal to me that…I do it without thinking about it.” Through their discussion on academic language and tutoring actions towards it, tutors normalized WME as academic language.

Tutors’ notion of voice through academic language appears to be an exception to that normalization. Though voice also went undefined by tutors, words such as “creative” (Eleanor), “style” (Tink), and “casual” (Ami) were used to describe it. Tutors seemed to conflate voice with non-standardized forms of English, especially African American Vernacular English in Tink’s case.

Standard language ideology’s stronghold on tutors is, initially, not very surprising. Research has previously suggested tutors may hold a standardized language ideology. Effinger-Wilson (2011) demonstrated that tutors, like other writing instructors, hold deficit perspectives towards nonstandardized dialect in academic writing; Kern (2019) found that tutors can have strong negative emotional reactions to challenges of WME; and Herzl-Betz (2022) found a connection between white tutors’ love of academic writing and the way “white grammars are positioned as academic norms,” (p. 53). However, what is significant about tutors’ standard language ideology is that the tutors in this study did not self-identify as holding a standard language ideology. Ami even identified as someone who doesn’t use WME or adhere to a standard language in their writing. The concept of linguistic justice was not unknown to these tutors. They’d done some reading around the concept in their tutoring education the previous fall, and were aware that the center they worked at sought to celebrate student writers’ linguistic diversity. To varying degrees, each tutor agreed with that mission. Thus, tutors’ expressions of standard language ideology are significant because they demonstrate that tutors may be unaware of how their tutoring practices promote standard language ideology still and that their socialization into this ideology may require more intense unlearning experiences.

Professors vs. Students

The opposing conceptualizations of academic writing and language as both professor determined rules and student centered voice bring up questions of authority over students’ academic writing. Who has the power and control over student writing? Professors or students?

There was a push-pull tension between the desire to empower students through using their own languaging practices and meeting the expectations of “the system” (Tink) tutors perceived as established by professors. Writerly choice and voice was encouraged at times, and rule-based tutoring aligned to tutors’ understandings of professor expectations was enacted at other times. Moments where tutors centered voice in their tutoring actions seemed intended to empower student writers. Eleanor in particular talked about voice in terms of power and control, but all three tutors emphasized that voice comes from writerly choice. Moments where tutors employed rules-based tutoring actions shifted the power to professors.

It is important to note that tutors discussed their perceptions; they did not actually know what professors expect from academic writing, but rather had made assumptions based on their own experiences and used these assumptions to guide students. This suggests that perhaps tutors themselves are restricting their help to prescriptive WME grammar rules instead of the actual professors. Recent scholarship by Schreiber & Worden (2019), however, suggests that the problem of preparing students’ for professors’ expectations of WME might not be “as insurmountable as it often appears,” (p. 68). Likewise, tutors did not know if voice, or how they conceptualized of it, was actually empowering to students. In fact, in my observations, when tutors provided only suggestions and deferred to student writers’ choices, the student writers would sometimes become frustrated in the tutoring sessions.

Additionally, tutors were unclear about why they made the choice to focus on one or the other at the specific times they did when asked about their decisions in the interviews after observation. This indicates that tutors are constantly negotiating their own conceptualizations, as Montgomery (2024) found in their study of tutors’ responses to their writing centers’ linguistic justice policy. This shapes their tutoring by leading to varied decision-making around which conceptualization, and therefore, whose authority to prioritize.

Academic Voice

While tutors felt tension between meeting their ideas of professor expectations and centering student voice, which resulted in conflicted tutoring, I argue that this does not have to be the case. In my interviews with tutors, a recurring theme in their academic writing support came up: “sounding academic”. Currently, academic language and, by extension, academic writing, are associated with WME and standard language ideology. Academic language as a language ideology is about the speakers as much as it is about the language used itself (Flores, 2020). This limits who gets to “sound academic” to those already fluent in WME.

However, academic language and WME are not one and the same despite the common conflation of the two. Academic language is simply the language used to produce academic writing, something Eleanor described as essentially the “writing you do in school or for school or for teachers.” Writing center tutors exist to help students with exactly that – writing for school. If tutors help student writers find their voice through the language they use to do academic writing, tutors can help students form an “academic voice” and help shift the meaning of “sounding academic” from being “posh enough” (Ami) and associated with the white middle class to something more attainable for all students such as simply using academic writing genre conventions like having a thesis.

Conclusion

With this research, I sought to provide writing center administrators with tutor perspectives in order to aid their development of linguistic justice tutor education. I found that tutors held on to a standard language ideology, even if they don’t recognize it as such, through their conceptualizations of academic language as rules expected by professors. I also found that tutors held tension with this conceptualization, also imagining academic language through a more student centered lens of voice. Because of these two opposing conceptualizations, tutors were not consistent in their tutoring sessions, taking up the different conceptualizations at different times.

These findings have important implications for tutor education. First, tutor education may need to do more to challenge or inform the ideas of professor expectations that tutors have. If tutors feel that students’ nonstandardized writing will not be accepted by professors, they are likely to reinforce WME expectations. Perhaps more opportunities for tutors to actually meet with professors and discuss expectations could be transformative professional development towards linguistic justice. Second, tutor education can help tutors reimagine what it means to “sound academic” by focusing on academic writing conventions such as having a thesis rather than WME grammar. Expanding what it means to “sound academic” expands access to who gets to be “academic”.

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Basta, H., & Smith, A. (2022). (Re)envisioning the Writing Center: Pragmatic Steps for Dismantling White Language Supremacy. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 19(1).

Blazer, S. (2016). What They Say: Writing Center Tutors and Transformative Staff Education [Doctoral Dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania].

Brooks-Gilles, M. (2018). Constellations across cultural rhetorics and writing centers. The Peer Review, 2(1).

Canagarajah, S. (2020). Transnational literacy autobiographies as translingual writing. Routledge.

Effinger Wilson, N. (2011). Bias in the writing center: Tutor perceptions of African American English. In L. Greenfield & K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 212-227). Utah State University Press.

Faison, W. (2018). Black Bodies, Black Language: Exploring the Use of Black Language as a Tool of Survival in the Writing Center. The Peer Review, 2(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/relationality-si/black-bodies-black-language-exploring-the-use-of-black-language-as-a-tool-of-survival-in-the-writing-center/

Fernandez, M. & McIntyre, M. (2025). Recoveries and Reconsiderations: Linguistic Justice and Storying Resistance to Generative AI. Pietho, 27(2).

Flores, N. (2020). From academic language to language architecture: Challenging raciolinguistic ideologies in research and practice. Theory into Practice, 59(1), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1665411

García, R. (2017). Unmaking Gringo-Centers. The Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 29–60.

Greenfield, L. (2011). The “Standard English” fairy tale: A rhetorical analysis of racist pedagogies and commonplace assumptions about language diversity. In L. Greenfield & K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 33–60). Utah State University Press.

Haltiwanger-Morrison, T. & Evans-Garriot, D.A. (Eds.). (2023). Writing Centers and Racial Justice: A Guidebook for Critical Praxis. Utah State University Press.

Heller, V. & Morek, M. (2015). Academic discourse as situated practice: An introduction. Linguistics and Education, 31, 174-186.

Herzl-Betz, R. (2023). Why do white tutors ‘love’ writing? In T. Haltiwanger-Morrison & D.A. Evans-Garriot (Eds.), Writing Centers and Racial Justice (pp. 47-66). Utah State University Press.

Kern, D. (2019). Emotional performance and antiracism in the writing center. Praxis, 16(2), 43-49. https://www.praxisuwc.com/162-kern

Krishnamuthy, S. (2022). Tutoring in a liminal space: Writing center tutors’ understanding and applications of translingual and antiracist practices. [Doctoral Dissertation, Rowan University].

Lerner, N. (2009). The idea of a writing laboratory. Southern Illinois University Press.

Lindquist, N. (2025).We Should Promote GenAI Writing Tools for Linguistic Equity. Writing Center Journal, 43(1). https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.2078

MacSwan, J. (2020). Academic English as standard language ideology: A renewed research agenda for asset-based language education. Language Teaching Research, 24(1), 28-36.

Montgomery, P. (2024). Doing (it) right: Writing center consultants’ re-entextualization of language ideologies. [Doctoral Dissertation, Michigan State University].

Nee, J., Smith, G. M., Sheares, A., & Rustagi, I. (2022). Linguistic justice as a framework for designing, developing, and managing natural language processing tools. Big Data & Society, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517221090930

Newman, B. & Gonzalez, R. (2017). Narratives of student writer and writing center partnering: Restructuring spaces of academic literacy. The Peer Review, 1(2).

North, S. M. (1984). The Idea of a Writing Center. College English, 46(5), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.2307/377047

Park, S. (2024). AI Chatbots and Linguistic Injustice. Journal of Universal Language, 25(1).

https://doi.org/10.22425/jul.2024.25.1.99

Pawlowski, L. (2024). Introducing linguistic antiracism to skeptics: A scaffolded approach. The Peer Review, 8(1).

Ray, C. & Goldin, E. (2025). “How I Speak Doesn’t Really Matter, What I Speak about Does”: Bipoc Tutor Voices on Linguistic Justice in the Writing Center. Praxis, 22(3), 32–45.

Rifenberg, J.M. (2020). The potential of writing center case study research design as public scholarship. In J. Mackiewicz & R.D. Babcock (Eds.), Theories and methods of writing center studies: A practical guide (pp. 141-149). Routledge.

Sabatino, L. (2023). Addressing racial justice through reimagining practicum to promote dialogue on campus. In T. Haltiwanger-Morrison & D.A. Evans-Garriott (Eds.), Writing Centers and Racial Justice: A Guidebook for Critical Praxis (pp. 103-119). Utah State University Press.

Salem, L. (2014). Opportunity and transformation: How writing centers are positioned in the political landscape of higher education in the United States. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), pp. 15-43.

Schreiber, B., & Worden, D. (2019). “Nameless, faceless people”: How other teachers’ expectations influence our pedagogy. Composition Studies, 47, 57–72.

Schreiber, B., Eunjeong, L., Johnson, J., & Fahim, N., (Eds.). (2022). Linguistic Justice on Campus: Pedagogy and Advocacy for Multilingual Students. Multilingual Matters.

Shelton, C., & Howson, E. (2014). Disrupting authority: Writing mentors and code-meshing pedagogy. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 12(1).

Sunstein, B. (1998). Moveable feasts, liminal spaces: Writing centers and the state of in-betweenness. Writing Center Journal, 18(2), pp. 7-26.

Thompson, F. & Hatch Pokhrel, L. (2024). GenAI: The Impetus for Linguistic Justice Once and For All. Literacy in Composition Studies, 11(2).

Thonus, T. (2001). Triangulation in the writing center: Tutor, tutee, and instructor perceptions of the tutor’s role. Writing Center Journal, 22(1), 59-82.

Toney, M. (2020). Reading between the lines: Language ideologies and tutor education readings [Masters Thesis, University of Central Florida].

Towle, B. (2024). Accidental outreach and happenstance staffing: A cross-institutional study of writing center support of first-generation college students. Writing Center Journal, 41(3), 72-86.

Tucker, K. & Bouza, E. (Eds.). (2024). Enacting linguistic justice in/through writing centers. The Peer Review, 8(1).