Zoe Smith, Auburn University

Caroline LeFever, North Carolina Union County Public Schools

Layli Miron, Indiana University

Abstract

What can consultants do to move students to return to the writing center? To identify strategies that accomplish this end, two undergraduate researchers and an advisor surveyed students who had repeatedly visited a single consultant. We then analyzed the data, coding consultant strategies and noting repeated occurrences. We also recorded appointments of consultants with high rates of returning clients, collecting transcripts detailing the strategies they use in first-time visits. Our research contributes to our field’s understanding of why some students return to the writing center and what students want from their consultant, intersecting with current conversations that acknowledge student writers as co-creators of writing centers and recognize peer tutors’ emotional labor. The consultation that we document and analyze may find use in consultants’ professional development.

Introduction

We begin with a narrative by co-author Caroline LeFever:

In my first year working as a peer consultant at my university’s writing center, I became increasingly aware of what my coworkers excitedly termed “repeat clients.” Several consultants told me it was simply a matter of time before I had repeat clients—that is, clients who schedule appointments with me regularly. I wanted to have my own repeat clients so that I could relate to the veteran consultants. My interest grew when I saw a pattern of certain consultants (including myself) having a larger number of repeat clients than others. It was normal for me and several other consultants to only have appointments with repeat clients in a given week, sometimes mixed in with a handful of first-time visits or clients with no preference for a certain consultant.

At the end of my first year, Layli (our writing center’s supervisor) gathered the consultants to set expectations for the upcoming academic year, encouraging us to develop our own projects for the benefit of the writing center. In response, I posed an interest: “I’ve noticed that many of us have many repeat clients. I don’t have a project in mind…but I’m interested in why repeat clients come back so often.” One of the other administrators in the room then said, “Well, that’s a great research question. You should follow that.” So, I did. Over the next several weeks, I worked on focusing my interest into a researchable question. Once we built our team, this task became easier as I had Layli’s experience and my colleague Zoe’s shared interest to rely on.

Caroline and Layli invited other consultants to join the project, an invitation taken up by Zoe. We knew we wanted to pursue our study within our own center, which serves a public research-intensive university in the Deep South with a student body of about 33,000 students. While both graduate and undergraduate students use our tutoring services and make up our tutoring staff, the center itself primarily serves and is staffed by undergraduates, such as Caroline and Zoe. Both Caroline and Zoe were rising seniors working toward degrees in secondary English language arts education at the time of this project’s beginning. We first considered, based on Caroline’s original inquiry, asking a question that focused on the client: “Why do they keep coming back?” or “What do clients look for in a consultation?” By considering pertinent scholarship and discussing how we wanted our research to serve our writing center, we refined our investigation, taking consultants’ work as our focus. Together, the three of us arrived at the following research question: “What strategies do consultants who have a relatively high number of repeat clients use in their tutoring, as observed from session transcripts and repeat clients’ perspectives?”

Literature Review

To contextualize the research question, we explore writing center literature about how regular visits to the center affect writers. The scholarly conversation, while rich, has not fully unearthed students’ rationale for returning to an individual consultant, which is where we stake the primary value of our study. In addition, we demonstrate how our project responds to calls in our field to center the voices of students who do or do not use the center and of undergraduate researchers.

Each semester, an influx of new and returning clients arrives at the writing center seeking feedback for both their personal and educational endeavors. Many writers come only once, perhaps to fulfill a course requirement or to get feedback on an especially high-stakes project, and never return. For these one-time visitors, their single interaction with a consultant may well make a difference in their learning (Miller, 2020). Yet, research suggests that students who use the writing center multiple times benefit more in terms of learning transfer (Bromley et al., 2016), self-reported writing development (Giaimo, 2017), and grades on their writing projects (Zuccarelli et al., 2022). Indeed, as the semester progresses, the writing center witnesses some students coming back a few times, occasionally bouncing from consultant to consultant, looking for the best fit. How do these regular visitors benefit from repeated writing center use—or does their relationship with the writing center risk overreliance? The answer to this question depends on how we as writing centers define our success.

In one view, a writing center’s success means building independent writers—instilling our knowledge in the students who visit us to such a degree that they no longer need us. According to this perspective, we should help a writer shift their thinking into that of a writing consultant, nurturing their reflexivity so that they can imagine the responses of their readers and adjust their approach accordingly. The epitome of failure would be creating clingy, dependent writers (Walker, 1995). Anxiety about reliance echoes historical fears among some writing center leaders about our services being perceived as remedial (Salem, 2016). According to the narrative of independence, supposedly reliant writers will struggle when they enter the “real world” and no longer have access to the free, friendly services of a writing center.

Yet, there is another possibility: that frequently visiting the center does not signal dependence or incapability, but instead, an admirable awareness that good writing, as an act of human-to-human communication, requires the input of other people. Writing scholars like Bruffee (1973), Lunsford (1991), and Healy (1994) assert that writing is always collaborative, necessitating feedback, no matter how advanced the writer. In this view, a mature writer recognizes the value of attentive readers—so, writing centers should aim to move writers toward such a mindset and habit.

Recent research implies that repeat visits do inculcate effective writing habits. In Schmidt and Alexander’s (2012) study, they found that writers who attended at least three sessions in a ten-week period had greater improvement in “writerly self-efficacy”—“beliefs about what and how they can perform as writers” (p. 1)—than those who did not attend any sessions. Similarly, Giaimo (2017) found that after three or more visits, students perceived themselves developing as writers. Sustained engagement with the writing center thus has a measurable effect on students’ confidence as writers. Bromley et al. (2016) found that, while single visits can benefit learning, “repeat writing center visitors […] are regularly engaging in high-road transfer [i.e., deliberate, mindful application of previous learning (Perkins & Salomon, 1992)] as a result of their writing center visits” (p. 8). The authors indicate the value of “recursive learning over time and at a pace set by the student” (p. 12), pointing toward the advantages of ongoing coaching relationships. One such relationship forms the focus of a study conducted by Severino et al. (2021), who coded an earlier and later meeting of a tutor-writer pair. Their analysis reveals that the tutor took a more collaborative approach in the later session, implying that, by meeting repeatedly, the dyad developed a relationship more conducive to empowering the student to take ownership and make decisions about their writing. It seems that recurring appointments between tutor-writer pairs can support engagement and collaboration.

Given these suggestions that sustained consultant-writer relationships benefit students’ learning, it follows that writing centers should encourage students to return. To that end, we need to understand what motivates writers to come back. In our search of the literature within writing center studies, although repeated visits come up on occasion as brief mentions in articles with other focuses (e.g., Thonus, 2002; Trosset et al., 2019), we did not find substantial research dedicated to this topic. We seek to fill a gap, therefore, by investigating students’ reasons for coming back to a specific consultant. The “meshing” or lack thereof between a writer and a consultant can determine whether the writer ever returns to the center (Wells, 2016), making their dyadic connection a worthy site of study. We perceive our study making two additional contributions to the field: as research that prioritizes what students who repeatedly use the writing center have to say about us in their own words and as an example of undergraduate research.

As other writing center practitioners have noticed, our field often researches the students who use the writing center—and sometimes, those who do not (e.g., Colton, 2020; Salem, 2016)—but seldom foregrounds their voices. Hashlamon (2018) points to a tendency to “attend to writers as recipients of tutoring” but not as “active participants in testing our pedagogical assumptions” (p. 5). Echoing the same concern, Hallman Martini (2023) asserts that “the student writer’s voice is strikingly absent” (p. 95). In the years since Hashlamon conducted a systematic review of writing center articles, some new studies have prioritized student writers’ perspectives, yielding insights that challenge conventional wisdom (Buck, 2018; Eckstein, 2018; Fledderjohann, 2023). By focusing on students’ reflections on their motives for returning to a consultant, we too prioritize student writers as knowledgeable co-creators of the writing center, helping unseat the assumption that they are mere beneficiaries.

In the spirit of uplifting student voices, two of the three authors of this study, Caroline and Zoe, were undergraduate students at the time of research and writing. In collaboration with Layli, Caroline’s and Zoe’s interests and insights drove this project. Various scholars have urged writing center leaders to devote more effort to mentoring their undergraduate tutors through processes of study design, conference presentations, and publications so that they can reap the rewards of conducting research (Efthymiou & Fallert, 2022; Fitzgerald, 2014; Keaton et al., 2022). Undergraduate tutors themselves have written of the powerful, sometimes transformative, impact of researching their writing centers (Cheatle et al., 2019; Saturday, 2018). Nevertheless, few research projects spearheaded by undergraduates make it to publication, so we hope to inspire more undergraduate consultants and research mentors to prioritize such work. To that end, we include a postscript reflecting on our experiences.

Research Methods

To pursue our research question, we took a two-pronged approach to collecting data so that we could get both big-picture perspectives from repeat clients via a survey and rich, specific examples from consultation recordings. Our primary instrument was a survey administered to repeat clients, which encouraged them to reflect on their reasons for returning to a certain consultant. With the goal of illustrating the strategies pointed out by the survey respondents, we also recorded sessions led by consultants who attracted a high number of repeat clients.

Survey

We decided to begin our research by first seeking writers’ perspectives and reasons for returning to a specific consultant in the form of a Qualtrics survey. We planned to then use these survey responses to frame our analysis of later consultation recordings.

Our Qualtrics survey featured a single prompt:

Please think about the peer consultant(s) you have visited more than three times at the Miller Writing Center and reflect on why you chose to come back to that person. In your response, please describe any or all of the following: What teaching strategies did they use that you found helpful? What interpersonal/communication skills did they demonstrate that you found appealing? What knowledge did they demonstrate that you found useful? What did that consultant do that set them apart from other consultants you had met with, if applicable? What else made you decide to return to this consultant? The more specific you can be in your response, the better! This survey only has one question because we’re hoping you’ll elaborate on your experience with the consultant(s) you returned to, telling us the story of why you returned to them.

This prompt was followed by a text entry field with a character limit of 20,000.

To identify potential participants, we obtained a list of all the students who had returned to a certain consultant three or more times in the previous academic year (2022–23). Eighty-five students met this criterion. We emailed them an invitation to take the survey along with the IRB-approved information letter. A $20 gift card incentivized participation; once a respondent submitted the survey, they were redirected to a separate survey where they entered their information to get the card. We kept the survey open from late September 2023 to late October 2023; during this time, 23 students responded (a response rate of 27%).

In analyzing the responses, we wanted to determine what the respondents found most attractive in their chosen consultant. To that end, we used a two-stage process of modified grounded analysis informed by Mackiewicz and Thompson’s (2014) coding scheme. We decided to first independently review the survey responses to reduce the possibility of influenced coding. Each researcher produced a list of themes from a holistic reading of the responses. Then, we came together and compared our themes, consolidating them into six codes—attitude, knowledge, pedagogy, familiarity, project management, and efficiency. For the second stage, we divided each survey response into smaller segments, each segment representing a complete idea (typically a claim followed by elaboration). After breaking the responses into segments, we collaboratively coded each segment over the course of several meetings. Typically, we unanimously selected the same theme for each unit. When we had differing opinions about the most applicable theme, we discussed the merits of each possibility and then came to a consensus. Layli would often defer to Caroline’s and Zoe’s opinions, conscious of how her position as their supervisor could influence the team’s decision-making.

Session Recordings

To recruit participants for the second component of the research process, we obtained a list of currently employed consultants who had two or more clients who visited them at least three times in 2022–23. Most consultants met this criterion, so we focused on those with the highest number of regular clients. Caroline and Zoe topped the list, but to avoid any conflict of interest, we excluded them as participants in the study. Four of the five consultants we invited agreed to participate.

With the goal of documenting one session per consultant, we identified face-to-face appointments that we could record. We chose to exclude asynchronous appointments since our focus was on synchronous interactions; we likewise discounted video-call appointments due to challenges with documenting the writer’s consent and privacy problems with recording. Based on our personal availability, we selected appointments to attend, seeking informed consent from both the writer and consultant when the writer arrived. After obtaining consent, the researcher recorded audio from the sessions via Zoom, a video conferencing application, using their smartphone’s mic. We used the “record to the cloud” feature, prompting Zoom to automatically generate a transcript, which we then corrected while listening to the recording.

With four transcribed consultations in hand, we individually coded each one, highlighting passages we believed to be illustrative of our six themes. After our independent analysis, we came together to compare passages, which led us to realize that one session—Jasper’s—stood out in providing the richest examples of consultant strategies mentioned in the survey responses and a wider array of our six identified themes (more information about Jasper can be found in the “Illustrative Consultation” section). Rather than shifting this article between four different writer-consultant interactions, we believed that centering one session would provide space for more detailed and focused analysis. Within our transcript of Jasper’s session, we selected excerpts of interest (also shared in the “Illustrative Consultation” section) and noted consultant strategies based on the themes we had developed from the survey responses.

Results of Survey: What Returning Writers Value

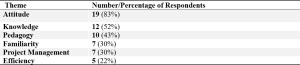

Using a modified grounded approach to analyzing the survey responses, we developed six themes that encompass nearly every idea expressed by the respondents, most of which relate to how they perceived their consultant. “Attitude” includes encouragement, kindness, humor, eagerness, patience, and other emotionally supportive attributes of the consultant. “Knowledge” relates to the consultant’s writing abilities and understanding of field- and genre-specific conventions. “Pedagogy” refers to the consultant’s instructional strategies and explanations of their feedback. “Familiarity” indicates the writer’s comfortable relationship with their consultant. “Project management” describes a consultant’s ability to break tasks into manageable steps and to coach the writer through the writing process. “Efficiency” describes the pace and productivity of the session(s). Table 1 provides the prevalence of each theme according to how many of our 23 respondents mentioned it at least once.

Table 1

Prevalence of Themes Across Responses

Discussion of Survey Responses

In the following discussion, we reveal what respondents have to say about why they returned to a certain consultant and present key takeaways. We order our analysis of the responses for each theme according to frequency. We name respondents by the order of their response (e.g., “Respondent 1”).

Attitude: 83%

Most respondents mentioned their consultant’s attitude (emotionally supportive attributes of the consultant), revealing writers’ attunement to the relational elements of a consultation—from smiles and laughter to encouraging remarks and praise. Respondent 22, for example, elaborates on their consultant’s listening:

Throughout my visits, the consultant I worked with demonstrated strong active listening skills throughout my appointments. I felt as though her sole focus was on me, my writing, and how to improve it, as it should be. I never felt that she was distracted or uninterested with anything I brought to her for assistance with, even if it included some technical aviation language. To the contrary, she seemed very interested in hearing about what I was writing about and how she could help me improve it from a writing standpoint.

The respondent emphasizes the consultant’s full attention to their needs. Other respondents likewise mentioned their consultant’s listening; for example, Respondent 17 explained, “[…] she was a good listener who always took the time to grasp my issues and the session’s objectives.” As a skill in interpersonal communication, active listening creates fluid conversations, and, according to these responses, shapes how writers perceive their consultant’s attitude.

Some respondents tied listening to patience. Respondent 7 explained how the consultant’s listening supported them: “They are patient and attentive listeners, allowing me to express my concerns and questions without feeling rushed.” Respondent 21 also said that their consultant “was very patient” and therefore “was able to build efficient rapport” during the sessions. A “friendly and patient” attitude endorsed by Respondent 20 seems to stem from skills in active listening. If a consultant is intent on listening and working with clients “safely and patiently,” as Respondent 23 phrases it, then the result is never making a client “feel ashamed or inadequate if [they] did not understand something.”

Beyond patience, some respondents emphasized how encouragement and kindness motivated them to return to the center. Respondent 2 recalled, “Both of these consultants were very kind and helpful which made me return multiple times.” Similarly, Respondent 5 wrote, “The peer consultants are personable, in [sic] which has made the appointment enjoyable. This has influenced me to make multiple appointments.” From these responses, we can observe a direct link between a consultant’s attitude and the motivation a student feels to return to that consultant.

Our survey responses suggest that if a writer sees their consultant as encouraging, friendly, patient, and respectful, they feel more inclined to return. As the most frequently mentioned theme, attitude appears to be a prominent motivator in writers’ desires to return to a specific consultant. However, as Respondent 9 stated, a consultant’s positive and encouraging attitude “does not mean they are necessarily extroverts, just that these are people [who] are good at one-on-one communication.” To move students toward repeat consultations, writing centers must teach and build interpersonal communication skills in their staff—not by hiring solely outgoing consultants, but those who are willing to do the work to make clients feel understood, encouraged, and confident.

Knowledge: 52%

Many of the 12 respondents who touched on the consultant’s perceived knowledge (writing abilities and understanding of field- and genre-specific conventions) focused on the norms of academic writing. Some respondents explained that the consultant’s specialized knowledge of writing in their discipline compelled them to return. For instance, Respondent 15 explained that they select consultants according to their “major and year of the college . . . because I also can save time to explain some specific terms” in the writer’s field. Similarly, Respondents 7 and 16 both said they valued the consultant’s knowledge of STEM writing, with Respondent 7 praising their consultant’s understanding of “the nuances specific to scientific discourse” and Respondent 16 remarking on their consultant’s “science background.” These respondents preferred to work with a consultant who demonstrated understanding of field-specific writing conventions.

Other respondents appreciated their consultants’ wide-ranging writing knowledge; for example, Respondent 22 commented,

While I am sure many consultants had enough knowledge to appropriately help me with my writing, I felt as though this consultant was very up to date on certain things that I wanted help with. Some of these things included research essay editing, proper MLA & APA citations, etc. For example, with the APA citations, she talked about how she had just gone through a class which required a lot of APA citations. Knowing that she had recent experience with this was beneficial.

In this case, the consultant’s apparent confidence in assisting with citations instilled confidence in the writer. Others praised their consultant for the scope of their expertise: “They have helped learn how to research for papers, create outlines, review citations. I’m able to go to them about any topic,” wrote Respondent 12. Respondent 17 echoed,

She was well-versed in writing conventions and norms. She could give justification for her recommendations and examples from numerous writing genres and disciplines. Her expertise was so extensive that it seemed well-informed and reliable.

When consultants showed knowledge of multiple genres, styles, and subjects, these writers felt they could trust their guidance. Advanced students, especially longer-term writing center employees, have an advantage in gaining a student’s trust since they have had more time to build their writing knowledge. While these writing tutors have more experience through their exposure to diverse writing projects in their consulting work and their studies, not all hope is lost for novice consultants.

While it appears that a consultant’s wealth of knowledge is a prominent factor in a writer’s desire to return, one response suggests that a consultant’s ability to figure out an answer is just as impactful as already knowing the answer. Respondent 4 provides some reassurance for novice consultants, commenting, “Aside that, even when they did not have an answer for my reason of being there, they would take their time and research to find the answer. That was always helpful. They know their stuff.” While the knowledge a consultant brings to a session matters, so does their willingness to learn alongside the writer.

In the effort to assess a consultant’s wealth of knowledge, writers may use someone’s academic status to judge their academic ability, which may result in a biased selection. Respondent 3 illustrates this point by stating, “She was a graduate student herself, which was vital: she had some degree of maturity in writing.” Here, the respondent explicitly mentions the consultant’s identity as a graduate student, revealing that the consultant’s academic identity marker may have informed their decision to return. This potentially biased selection process can extend to consultants with other identity markers, especially those whose markers get read by writers as less authoritative (Denny et al., 2018; Faison & Condon, 2022; García & Sicari, 2022; Greenfield & Rowan, 2011). To illuminate and redress possible inequities in students’ selection of consultants, more research about how consultant identity markers correlate with client booking rates must be conducted.

Pedagogy: 43%

Ten respondents cited consultant pedagogy (teaching strategies and explanations of feedback) as a reason for returning to the writing center. Many respondents noted the consultant’s ability to provide both affirming and constructive feedback, with one client naming the ever-popular “compliment sandwich.” An illustration of effective pedagogy comes from Respondent 17: “Although she gave constructive criticism when needed, she did it in a nonjudgmental and helpful manner. As a result, I felt free to ask questions and share my writing struggles in a relaxed and open setting.” This writer explains that the consultant’s pedagogical move of giving “nonjudgmental” and “constructive” feedback impacted their own attitude, prompting them to play a more active role within the session.

Multiple respondents also mention specific strategies that the consultant used to engage with the student’s writing. One such strategy is reading aloud, which Respondent 14 implies is effective in revising: “This technique aids in pinpointing problematic areas within my writing. This strategy can also be used while I review my writing.” This writer recognizes that they can transfer this technique to their independent revision process, which suggests that students value consulting strategies that they can use beyond the writing center.

Most comments related to pedagogy praise consultants for their verbal communication. Respondent 7, for instance, comments, “Whether it’s explaining the structure of a research paper, helping me improve my data analysis section, or fine-tuning my citations, their ability to simplify and clarify intricate topics has been invaluable.” Here, the writer commends the consultant’s ability to communicate about a range of writing skills in terms that the writer understands. This suggests that not only is the consultant’s knowledge beneficial for clients, but also the consultant’s ability to express that knowledge through pedagogy. Good pedagogy, it seems, does not require mastering a checklist of consulting strategies, but attuning to the learner’s needs and conversing attentively.

It is important to note that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to pedagogy. Across the survey responses, numerous pedagogical moves were mentioned, suggesting that there is no one strategy that works for every writer who walks into the writing center. So, for a consultant to attract multiple repeat clients, their pedagogy must be ever-evolving to meet the specific needs of the writer before them.

Familiarity: 30%

Seven respondents shared that they returned to a consultant because of the consultant’s familiarity with the writer, their project, and/or their needs, or because the writer got comfortable with a consultant by virtue of meeting more than once. In the words of Respondent 9, “I don’t have to re-explain what I’m going for in the assignment.” Students can find needing to re-explain their project and their goals to multiple consultants to be tedious, so the choice to return to the same consultant can be strategic. As Respondent 14 wrote, “The primary motivation behind seeking consultation services again is she or he has gained a better grasp of academic writing within my field.” This writer implies they have invested in training the consultant to be a good helper, calling into question the supposed division between “helper” and “helped.” Along similar lines, Respondent 16 commented that over time, their consultant “could see the struggle with writing such a big paper”; the writer seems to have almost intentionally triggered the consultant’s sense of empathy, enabling the writer to feel validated in their consultation.

Building on this sense of empathy in recurring pairs, multiple respondents commented on the comfort of meeting with a known person. For example, Respondent 18 described how they “clicked” with certain consultants, and Respondent 19 recalled building “rapport” over time. Respondent 22 reflected on why familiarity set them at ease:

I am someone who doesn’t like change. The main reason why I tried to work with the same consultant when my schedule allowed is because I was familiar with her. It makes me a lot more comfortable to visit when I know who I am going to be seeing, how they operate, how they give feedback, etc. She also seemed to have a better understanding of some of my frequent errors, which I believe helped her catch some of my more frequent mistakes. I preferred this over meeting someone new and having to adapt to their style of things. While I know different viewpoints can be good, and I did take the opportunity to meet with a few other consultants, familiarity was my greatest draw to returning to the same person.

This writer acknowledges a potential downside of loyalty to a single consultant. If a writer exclusively visits one consultant, they miss perspectives that others could contribute. Nonetheless, for some writers, sticking with a single consultant yielded not only intellectual but also emotional benefits.

Project Management: 30%

Seven respondents mentioned project management (a consultant’s ability to break tasks into manageable steps and to coach the writer through the writing process), portraying their writing consultant as a coach who collaborated on creating writing schedules and manageable plans for complex assignments. Respondent 8 provides an example of this project managerial role:

Every time I returned to the [writing center] with the same person, I always left understanding the material better and felt more comfortable with my assignment. The teaching strategy they used each time I had an appointment helped me by defining the essays [sic] requirements and rubric breakdown. They would give a layout of what the assignment was asking for and how to tackle the essay head on.

In this response, the client notes the consultant’s ability to provide actionable steps. It seems that a consultant’s ability to facilitate and structure a client’s writing experience both inside and outside of the session can draw writers to the center.

Respondents also appreciated consultants’ role in setting goals for them to accomplish by the next session. One such example comes from Respondent 16, who states,

What set the writing helper apart was that they understood that in the short hour that we had that I could do more work outside of the hour than just over the hour time frame that we had. Meaning that if there was a section of the writing that we both had difficulty rewriting that we would try to look around the section on what I am trying to convey and make a plan on what needs to be worked on before the next meeting.

In this instance, the writer and consultant met multiple times for the same assignment. The writer chose to return because the consultant helped them create a plan for their independent work. Respondent 16’s comment suggests that, with regular meetings, consultants can serve as an accountability partner for writers working on extensive projects.

Efficiency: 22%

Most of the few respondents who mentioned efficiency (pace and productivity of the session) implied that their scarce time shaped their choice of consultant. For example, Respondent 15 commented,

Slot time was also a big contributor for me to make a decision and keep working on the same consultant. I, as an international student, usually need more time to work on a paper, and time usually goes beyond my plan so I used to cancel daytime appointments and save more time until the night and bring the better version of the paper to consultants. So my reservations are more concentrated on the consultants working at nighttime.

This writer prioritizes time, naming “slot time,” “time to work,” and time of day as factors. They further explain, “The reason for making several appointments with the same consultant was that I can save time. Basically, I don’t have to explain my topic and concerns for my thesis again and again.” Every minute of the session seems to be precious for this writer, with time spent re-explaining viewed as a waste. Other respondents praised consultants who understood “that time is valuable” (Respondent 16) or who “help me with the goals I check off and teach in that way” (Respondent 9). These writers appreciated consultants who adhered to an agenda and managed session time.

Efficiency turned out to be the least frequently mentioned factor, which surprised us, given academic culture’s focus on productivity and students’ packed schedules. Perhaps the busiest students simply do not come to the writing center, viewing a 50-minute conversation with a writing consultant as an implausibility. Notably, our survey respondents came to the writing center in the 2022–23 academic year, when we offered only a handful of asynchronous appointments. We suspect that, with all appointments being available for asynchronous participation starting in summer 2023, our most time-strapped, efficiency-minded clients may have switched to that modality.

An Illustrative Consultation

To illustrate some of the most prevalent themes raised by the writers who responded to our survey, we next delve into an exemplary consultation. The consultant, whom we call “Jasper,” worked for our center from fall 2022 until he finished his undergraduate degree in spring 2024. In his first year, he attracted eight students who visited him three or more times. In fact, each of these “regulars” averaged six and a half visits. In our center, where writers can choose between some 35 consultants, the number and frequency of Jasper’s recurring visits stand out, making him one of our most in-demand consultants. This fact suggests that writers like what Jasper is doing. To illustrate what he does, we present and analyze four moments from the consultation we recorded in fall 2023 in chronological order. The writer, whom we call Alex, is an interior design major working on both their cover letter and résumé as part of a class assignment to prepare job application materials. Jasper and Alex met face-to-face in our center, and this was their first session together. Each of the four following sections starts with a sentence of grounding context, continues with an excerpt from the session transcript, and ends with an analysis of Jasper’s consulting strategies. Following these four sections is a brief discussion of the two themes we do not see within the transcript––familiarity and project management––and why these might not be illustrated in this particular session.

Transferable Skills

In the following excerpt (at around 05:37), Jasper and Alex review the writer’s cover letter and discuss communicating the writer’s proficiency in business management software systems.

Jasper: Like you… I do like how you use this. Like, I’m guessing other firms have similar systems where they, like, organize.

Alex: Yeah.

Jasper: Okay, so definitely include that, right?

Alex: Okay.

Jasper: ’Cause…

Alex: I’m gonna just write on this because…

Jasper: Yeah, go ahead.

Alex: Okay. So… and then… classic…

Jasper: Mhmm.

Alex: Okay. And then, but yeah, I see what you’re saying.

Jasper: Yeah, I mean, it’s the same thing with… For example, here, right? We use, uh, a scheduling system. A lot of places use scheduling systems. So being like, “Oh, I used systems like this before” always looks good, ’cause like, “I have experience in this type of industry.”

Alex: Yes. I’m just, like, what’s the word? It’s, like, “versati-…”

Jasper: Versatility?

Alex: I don’t know. It’s something like, it’s like, “Okay, this is like a skill that I’ve… it’s been… it’s useful for…”

Jasper: Transferable?

Alex: Yeah.

Jasper: Something like that?

Alex: I’m not sure that’s how you spell it, but… okay.

Jasper: No, it took me about four years to learn to spell “independent,” because I kept putting an “i” instead of an “e.”

In this exchange, we see Jasper’s pedagogy in his ability to explain feedback, knowledge about persuading readers of application materials, and attitude of humility and humor. He teaches Alex about highlighting transferable skills in their cover letter, giving them an example from his own work context. Jasper illustrates that his own ability to navigate one scheduling system could show prospective employers that he has the savvy to use other systems, and he explains that Alex should consider how their own specific experiences provide evidence of broader skills. This lesson takes little more than a few sentences, and along the way, Jasper and Alex both participate in the conversation. Jasper does not pontificate upon his knowledge of communicating transferable skills on job applications. Instead, he subtly cues Alex to engage and checks their understanding with simple closed-ended questions (“right?” “Something like that?”).

This excerpt ends with Jasper’s signature self-deprecating humor. He levels the hierarchy between him and Alex as he pokes fun at his own spelling struggles, implying that Alex should feel no shame about spelling. Overall, within a few moments of conversation, Jasper skillfully balances sharing his expertise in writing with conveying a sense of “peerness” to set Alex at ease.

Persuasive Numbers

At this point in the session (around 13:26), Alex and Jasper have moved to revising Alex’s résumé and discuss the importance of quantifying data in describing work experience.

Jasper: Okay. So, on the first one, for example, you say, “Worked on floorplans, various graphics in AutoCAD.” Um… if possible, you want to get as, as data driven as you can. So if you have an idea of how many you worked on…

Alex: Okay.

Jasper: If there’s something like that… And feel free to be, like, if you did… Let’s say you did, uh… 12, say “10 plus.” Because that looks like, “Oh, it’s more than 10,” which it is.

Alex: Yeah, I see what you’re saying.

Jasper: So, something like that. For example, like on mine, I have, like over 250 sessions helping clients. I have had over 250. It’s only 252, but… You know, it’s over 250.

Alex: Gotcha. Yeah.

Jasper: Um… But any, any numbers that you have and you can tie back into these, I always recommend adding them ’cause they show concrete. Concrete in what you’ve done.

Alex: Okay.

Jasper: I’ll make a note of that too. Um… [Reads] “Assisted at a mini-installation in Mountain Brook, Alabama, for a installation out of Pennsylvania.” [Quits reading] That looks good. I like right here, when you say, “Oh, a one-million-dollar design.” That’s amazing. That’s what you can do in here, right?

Alex: A very concrete, yeah.

From this exchange, we see Jasper’s knowledge of conventions in application documents, pedagogy in how he imparts that knowledge to Alex, and attitude as he praises Alex’s achievements. Jasper demonstrates expertise in the typical conventions, requirements, and audiences of résumés. Pedagogically, he uses the technique of modeling, furnishing an example from his own résumé of how to use numbers to persuade. Joking about his own use of numbers, Jasper uses humor to convey his encouraging attitude toward Alex. His strategies, in sum, convey respect and care for Alex.

A Sigh

Here (at around 16:28), the writer-tutor pair continues their discussion of Alex’s résumé, pausing for a moment on Alex’s experience working at a local acai bowl shop.

Jasper: Uh… [Reads] “Gained experience in customer service, assembled acai bowls.”

[Quits reading] You’re a professional. How do you say that? Is it a-sigh, a-sigh-ee?

Alex: It’s ah-sigh-ee.

Jasper: Acai, ok. I’ve always wondered.

[Alex laughs]

In this excerpt, Jasper expresses a jovial attitude toward Alex that builds rapport. As Jasper reads Alex’s writing aloud, he stumbles on the pronunciation of “acai” and asks Alex for clarification. This then leads to a comical exchange, as shown in Alex’s laughter. By sharing a joke, the pair establishes a friendly, low-stakes atmosphere, enabling collaboration surrounding Alex’s writing. Consultants may be perceived by clients as having a limitless wealth of writing knowledge, but in asking for Alex’s expertise on pronouncing “acai,” Jasper steps into the position of “co-learner,” with the writer as facilitator of this learning.

Worktime

Alex and Jasper have now finished their discussion of Alex’s cover letter and résumé (at around 22:56) with a considerable amount of time remaining in their session.

Jasper: Okay, um, well, you do have 26 minutes left. Uh, you can either sit here and work on this on your own, if you want, or you’re free to go. I’m not going to kidnap you, so…

[Both laugh]

Alex: Um, I might go ahead and make some adjustments, since… While it’s fresh, like, on my mind. And then, after that, I think I’ll be good.

Jasper: Okie-doke.

Alex: Yes.

Jasper: I’ll be here working on that message while you do that.

Alex: Okay, thank you.

[21 minutes of silence while client works on writing]

Jasper: We have about four minutes. That’s—I don’t want to interrupt, but I do want to see if you have any questions or anything I can help you with?

In the final segment of the consultation, Jasper expresses both pedagogy and attitude in offering Alex time to update their document. What is noteworthy here is how Jasper presents the idea of independent work time, a pedagogical technique that scaffolds the often-challenging task of using feedback to make revisions. Jasper does not mandate Alex to stay at the table and continue working, but instead presents choices of how to spend the time remaining in the session, giving them agency over their own writing process. Then, to mitigate the potential perception that there is a right choice, Jasper expresses a comedic attitude in making a lighthearted joke about not “kidnapping” Alex. After Alex accepts Jasper’s offer to stay and work on the project, Jasper then shares that he will occupy himself by writing the appointment summary report. In doing this, Jasper creates an equalizing environment where both he and Alex are writers working on their writing tasks. As a result, Alex can make revisions without feeling watched. Another pedagogical move worth mentioning is Jasper’s check-in with four minutes remaining in the session. After giving Alex time to work through the feedback, Jasper follows up to see if there are any questions or concerns that Alex encountered while writing independently. This check-in provides Alex with an additional opportunity for support—which Alex takes, asking Jasper for his opinion on the résumé’s design.

The pedagogical move of providing space within the session for the writer to work and ask questions also suggests a level of efficiency in Jasper’s consulting strategy. As is evident in Jasper’s repeated mentions of time remaining in the session, he is aware of pacing. Jasper’s mindfulness of the writer’s time allows Alex to increase their productivity and leave the writing center with much of Jasper’s feedback addressed.

Notable Absences

In our discussion of the session transcript, two of our six themes are notably absent––familiarity and project management. Because our identified themes are derived from survey responses of repeat clients, the theme of familiarity, which relies upon a pre-existing relationship between writer and consultant, is irrelevant in a first-time appointment like Alex and Jasper’s. Project management similarly depends on context, usually germane to larger projects; cover letters and résumés typically constitute shorter tasks.

Takeaways and Next Steps

We hope that our project will inspire other writing center practitioners to study the recurrent pairings of consultants and writers in their writing centers. One of our study’s main limitations was its small number of participants and local scope. Were the same survey to be administered at other writing centers, and were the researchers to use the same modified grounded coding method we employed to identify themes, they would likely find different results due to varying contexts. Since we designed our approach to be replicable, results from other institutions could be aggregated to reveal how different student bodies may value different competencies in writing consultants.

Operating within the strict time constraint of Caroline’s and Zoe’s graduation in May 2024, we were unable to explore other angles of repeat visits, leaving work that we hope will be taken up by other researchers. For instance, we focused on writers’ perspectives; what do consultants think about repeated visits, which can sometimes instill not pride and satisfaction, but dread? Additionally, to capture a more complete illustration of our identified themes, we could have recorded more than one session of each consultant and tracked themes across these sessions. For instance, in our discussion of Jasper’s transcript, two themes were notably absent—familiarity and project management. If we had consciously paired each consultant with a repeat client, we would have gotten more information about the particularities of repeat sessions and the evolution of writer-consultant relationships across sessions. This information could be used to model healthy writer-consultant relationships in consultant training modules and increase the number of repeat sessions in the writing center. Lastly, we excluded asynchronous and synchronous virtual appointments from our study. How do the affordances and constraints of these digital modalities affect a client’s inclination to return to a consultant? With our study’s limitations as a caveat, we offer several takeaways from our project.

Our respondents prioritized consultants’ attitude far above other factors. Logically, when writers come away from a session feeling less stressed, which one study indicates is a common outcome (Grendell et al., 2023), they would feel motivated to return. Yet, our center’s tutor education revolves around pedagogy and knowledge, advancing our consultants’ understanding of effective consulting techniques and of genre conventions, grammatical concepts, multimodal design, and other “hard skills.” For our respondents, though, it seems that “soft skills”—the consultant’s emotional intelligence and sociability—are paramount. We also wonder whether the way writers perceive attitude may disadvantage certain consultants who do not enact the emotional support expected by writers because of neurodivergence, cultural upbringing, or introversion. Additionally, how might similar biases impact a consultant’s frequency of clients, let alone repeat clients? It can be disheartening for a consultant to see coworkers attracting returning writers if, despite their efforts, they are not enjoying the same success.

This concern intersects with growing recognition of emotional labor as a cornerstone of writing center work and calls for center leaders to provide tutors with more training on this subject (Driscoll & Wells, 2020; Im et al., 2020; Mannon, 2021; Nelson et al., 2022). Mannon (2021) asserts that “[e]motional labor suffuses every stage of consultations” (p. 148), and that skills such as setting the student at ease, engaging them, and building their confidence can be learned. In light of this recent scholarship and our respondents’ prioritization of attitude, Layli is working to more explicitly teach interpersonal skills within a dedicated unit of new consultant training. Such training might better prepare consultants who come to the job with varying emotional IQs by, as Mannon urges, approaching emotional labor as “a craft and practice over innate skill,” just as we imagine writing to be (p. 147).

Considering attitude together with the other top themes, knowledge and pedagogy, we believe that our findings, especially the excerpts of Jasper’s consultation, could give new consultants ideas for how they can emulate “in-demand” coworkers. Various scholars have analyzed consultant strategies and moves within consultations (e.g., Cui, 2020; Hill & Helme, 2023; Lundin et al., 2023; Mackiewicz & Thompson, 2014). Such scholarship advances our field’s understanding of the range of techniques used by writing consultants, but these studies may be inaccessible to novice consultants, at least compared to the consulting story that unfolds in Jasper’s session. Indeed, over several years of running tutor education, Layli has noted consultants’ preference for brief readings, videos, and podcasts that provide jumping-off points for discussion in the context of professional development. We plan to share the excerpts of Jasper’s session with other consultants to inspire them—not to mimic Jasper, but to consider how they can capitalize on their own strengths.

One additional takeaway in our era of hype and horror around generative artificial intelligence (AI) pertains to the human-to-human interactions of consulting. With educational technology companies releasing ever-smarter products to provide feedback on writing, the future of writing centers seems uncertain, especially if, in budget crunches, administrators decide a campus-wide subscription to a writing app would be cheaper and more efficient than a cadre of writing consultants. Yet, at least among our respondents, only a handful mentioned the efficiency of their consultant as a desirable trait. Generally, the productivity of a session mattered far less than how their consultant made them feel. While AI “tutors” will outstrip a human consultant in speed and access to information, we offer the distinctly unmechanizable experience of sitting down with a person who cares to talk about ideas that matter, as suggested by the most frequently mentioned theme of attitude.

More broadly, we hope that our study may complicate the common valorization of self-reliance, i.e., we’re trying to create strong, independent writers. This superficially innocuous belief can lead to disparagement of “needy” students, and the consequent impetus to manage such students can enact ableism (Kleinfeld, 2023). Moreover, it defies the reality proven by any book’s acknowledgments section that even professional writers need a network of support, especially in the form of attentive, caring readers. Just as importantly, the warm relationships formed over repeated visits, over the minutes and hours spent pondering the myriad decisions in writing, may well help a student feel more at home in higher education.

Postscript: Reflection on Our Undergraduate Research Experience

As young researchers—two of us undergraduates, and one early in her career—we want to share our personal reflections on our research experience to encourage other young scholars.

Caroline’s Reflection

As an undergraduate, the thought of participating in a research study had not once crossed my mind; in fact, I had a predilection for avoiding research. I often felt incredibly out of my own depth and knowledge; it was just something I did when writing research papers for school. These happened to be my least favorite papers to write. I felt that they eradicated my voice and had such a formulaic mantra that they were impossible to perfectly emulate. However, research means so much more to me now than a tedious endeavor I was forever unable to succeed at.

The process of this research study, through its initial undertaking in the form of my personal interests to its current fruition as an article, has taught me the importance of collaborative research and using distinct writing voices and thoughts. Layli, the most involved mentor I have ever worked with, clearly modeled effective research thought processes at the beginning of this project and then continued modeling in the form of research strategies, methods, and composition. She was my go-to—always ready to answer my latest slew of questions and offer advice for revisions and edits. The ability to draw on Layli’s knowledge and experience was invaluable. With Zoe, it was our differences that made the research process effective. Where I am often unorganized, Zoe always knew what was coming next; where Zoe might have been hesitant, I would jump in headfirst; when I felt overwhelmed or out of my depth, Zoe knew ways to keep me focused and encourage me. We worked well together because of our contrasting personalities and identities.

During the process of collecting and analyzing data, we had the opportunity to present our results at a conference. This, again, was something I had never done before. Public speaking has always tormented me; in fifth grade I had a horrible experience presenting as Daniel Boone (I remember it quite vividly), and I could never present again without severe anxiety. However, the familiarity I had, the intimacy even, with this project and my collaborators was such that I felt confident enough to stand with them and present. Speaking in a formal setting to other scholars and academics was the farthest from comfortable I had ever been, but through conducting this project and presenting our findings, I was able to overcome my fear and speak with ease. I point to the moment our presentation concluded as the peak of my undergraduate studies. Never have I ever been prouder of myself. This crowning moment was only possible through being encouraged and cultivated by my peers and administrators at the writing center and through hard work that was not overlooked.

Zoe’s Reflection

My experience in writing center research widely deviated from my past undergraduate research experience. In my previous major of exercise science, I was a research assistant in a kinesiology lab where my primary responsibilities were cleaning equipment, assisting with data collection, copy-editing graduate researchers’ writing, and other “behind the scenes” work that would not be acknowledged in the published records of research. While I gained valuable knowledge about the inner workings of quantitative research, I was not often asked for my input. In this lab, my research team asked for my time, not for my knowledge.

In my research experience at the writing center, however, I felt seen and valued as a member of the research team. From the very beginning of the research process, Layli positioned both Caroline and me as having valuable knowledge to contribute. At each step of the research process, my insights were expressly asked for and listened to with intent. We openly discussed expectations and timelines when divvying up research responsibilities at our regular meetings. As a result, I had agency in selecting what tasks I had the space to complete and when I would realistically be able to have them completed. No task felt like “grunt work.” For each task I completed, I saw the value in its contribution. This research experience felt truly collaborative and meaningful, which made me feel empowered as an undergraduate researcher.

Co-presenting at a conference with my research team was a pivotal moment in developing my identity as both a professional and scholar. Initially, the feat of giving a fifty-minute presentation to a group of established members of the writing center community was daunting. However, intimidation evolved into excitement as we progressed through the research. Reflecting on this change in mindset, I believe that the support I felt from my research team sparked this evolution. At the conference itself, I felt validated as a contributor to the community of writing center scholars. Immediately following our presentation, attendees gave us glowing feedback and interacted with us as peers. Being seen as a writing center scholar by other writing center scholars was an unforgettable experience.

Layli’s Reflection

As I consider undergraduate research, I think back on my own college experience, which gave me opportunities to go to conferences and conduct a study on students’ experiences with writing instruction. The director of the writing center where I worked for three years brought cohorts of consultants to writing center conferences. Attending a joint IWCA/NCPTW conference as a sophomore filled me with ideas to bring back to my consulting work. Later in my college years, for my senior thesis, I wanted to try out qualitative research, and I was fortunate to find a generous advisor in the college’s ESOL director, who coached me through every step of the unfamiliar process of designing a study, getting IRB approval, recruiting participants, and conducting and coding interviews. Both mentors, Laura Greenfield and Mark Shea, built my confidence as a young scholar and prepared me for graduate study.

Today, I can pay forward the excellent mentorship I enjoyed as an undergraduate, working as I do with peer consultants throughout their years at the writing center. I want each consultant to find meaning in this job—and to leave the center better than when they arrived. To that end, I encourage students to apply their talents and interests to advance our mission, offering opportunities to create curricula, present at conferences, and pursue extra professional development. With the consultants who answer the call to rise from job-holder to innovator, we start to feel like colleagues, like intellectual partners, instead of supervisor and subordinate. That collegiality is precisely the feeling I had working with Caroline and Zoe on this project, making it, for me, the highlight of the year we spent researching. At every phase, Caroline, Zoe, and I were genuine collaborators, ideating and planning together.

Our experience has realized my idealistic vision of the writing center: the peer consultant position can be so much more than a part-time job. It can be a space where students can give back to the campus community by serving other students, test their teamwork and leadership skills, participate in experiential learning to complement their coursework, and even find a sense of vocation that will guide their career in any field.

References

Bromley, P., Northway, K., & Schonberg, E. (2016). Transfer and dispositions in writing centers: A cross-institutional, mixed-methods study. Across the Disciplines, 13(1), 634-643. wac.colostate.edu/atd/articles/bromleyetal2016.cfm

Bruffee, K. A. (1973). Collaborative learning: Some practical models. College English, 34(5). doi.org/10.2307/375331

Buck, O. (2018). Students’ idea of the writing center: First-visit undergraduate students’ pre- and post-tutorial perceptions of the writing center. The Peer Review, 2(2). thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-2/

Cheatle, J., Pebbles, K., Sargent, A., Wansitler, C., Laws, A., Wahl, R., Carroll, M., & Edara, R. (2019). Creating a research culture in the center: Narratives of professional development and the multitiered research process. Writing Center Journal, 37(2), 7–248. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1882

Colton, A. (2020). Who (according to students) uses the writing center?: Acknowledging impressions and misimpressions of writing center services and user demographics. Praxis, 17(3), 29–43. praxisuwc.com/173-colton

Cui, W. (2020). Identity construction of a multilingual writing tutor. The Peer Review, 3(2). thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-3-2/

Denny, H., Mundy, R., Nayden, L. M., Severe, R., & Sicari, A. (Eds.). (2018). Out in the center: Public controversies and private struggles. Utah State University Press.

Driscoll, D. L., & Wells, J. (2020). Tutoring the whole person: Supporting emotional development in writers and tutors. Praxis, 17(3), 16–28. praxisuwc.com/173-driscoll-wells

Eckstein, G. (2018). Re-examining the tutor informant role for L1, L2, and Generation 1.5 writers. The Peer Review, 2(2). thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-2/

Efthymiou, A., & Fallert, R. (2022). Redefining collaboration through the extended work of writing center tutors: How undergraduate research expands opportunities for collaboration in higher education. College English, 84(6), 638–651. doi.org/10.58680/ce202231993

Faison, W., & Condon, F. (Eds.). (2022). Counterstories from the writing center. Utah State University Press.

Fitzgerald, L. (2014). Undergraduate writing tutors as researchers: Redrawing boundaries. The Writing Center Journal, 33(2), 17–35. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1766

Fledderjohann, M. (2023). Intended and lived objects of learning: The (mis)aligned purpose and reported effects of writing center instruction. Praxis, 21(1), 17–31. praxisuwc.com/211-fledderjohann

García, R., & Sicari, A. (Eds.). (2022). Have we arrived yet? Revisiting and rethinking responsibility in writing center work [Special issue]. Praxis, 19(1). praxisuwc.com/191-full-back-issue

Giaimo, G. (2017). Focusing on the blind spots: RAD-based assessment of students’ perceptions of community college writing centers. Praxis, 15(1), 55–64. praxisuwc.com/giaimo-151

Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (Eds.). (2011). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. Utah State University Press.

Grendell, M., Pyper, B., Elmer, J., Overly, B., & Hammond, M.(2023). Effects of writing center-based peer tutoring on undergraduate students’ perceived stress. Praxis, 20(3), 31–40. praxisuwc.com/203-grendell-et-al

Hallman Martini, R. (2023). Keynote: Butting heads and the agency to yield: Maverick considerations in the writing center. Writing Center Journal, 41(2), 87–99. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1950

Hashlamon, Y. (2018). Aligning with the center: How we elicit tutee perspectives in writing center scholarship. Praxis, 16(1), 5–19. praxisuwc.com/161-hashlamon-1

Healy, D. (1994). Countering the myth of (in)dependence: Developing life-long clients. WLN, 18(9), 1–3. wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v18/18-9.pdf

Hill, H., & Helme, N. (2023). Pursuing transitive learning: A graduate student’s experience of learning and implementing transfer theory in the writing center. The Peer Review, 7(2). thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-7-2/

Im, H., Shao, J., & Chen, C. (2020). The emotional sponge: Perceived reasons for emotionally laborious sessions and coping strategies of peer writing tutors. Writing Center Journal, 38(1), 203–228. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1925

Keaton, M., Schoppe, A., & Oliver, D. (2022). Helping undergraduate tutors conduct and disseminate research: A practical guide for writing center administrators. Praxis, 20(1), 2–12. praxisuwc.com/201-keaton-et-al

Kleinfeld, E. (2023). The no-policy policy: Negotiating with (neurodivergent) clients. WLN, 47(4), 24–31. doi.org/10.37514/WLN-J.2023.47.4.05

Lundin, I. M., O’Connor, V., & Wynn Perdue, S. (2023). The impact of writing center consultations on student writing self-efficacy. Writing Center Journal, 41(2), 7–25. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1937

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3–10. jstor.org/stable/43441887

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2014). Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies, 42(1), 54–78. compstudiesjournal.com/archive/

Mannon, B. (2021). Centering the emotional labor of writing tutors. Writing Center Journal, 39(1), 143–168. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1962

Miller, L. K. (2020). Can we change their minds? Investigating an embedded tutor’s influence on students’ mindsets and writing. Writing Center Journal, 38(1/2), 103–130. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1922

Nelson, M., Weaver, K., Deges, S., Ruengvirayudh, P., Garcia, S., & Dunn, S. (2022). Does peer-to-peer writing tutoring cause stress? A multi-institutional RAD study. Writing Center Journal, 40(3), 21–37. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1016

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1992). Transfer of learning. In T. Husén, & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (2nd ed., pp. 425–441). Pergamon.

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions…decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147–171. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1806

Saturday, E. (2018). Reflecting on the research: Personal lessons from the IWCA collaborative. WLN, 43(3), 26–29. doi.org/10.37514/WLN-J.2018.43.3.05

Schmidt, K. M, & Alexander, J. E. (2012). The empirical development of an instrument to measure writerly self-efficacy in writing centers. Journal of Writing Assessment, 5(1). escholarship.org/uc/item/5dp4m86t

Severino, C., Egan, D., & Wells, A. (2021). Comparing tutoring strategies in recurrent tutorials. WLN, 46(3–4), 19–26. wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v46n3/severinoetal.pdf

Thonus, T. (2002). Tutor and student assessments of academic writing tutorials: What is “success”? Assessing Writing, 8(2), 110–134. doi.org/10.1016/S1075-2935(03)00002-3

Trosset, C., Evertz, K., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2019). Learning from writing center assessment: Regular use can mitigate students’ challenges. Learning Assistance Review, 24(2), 29–51. nclca.wildapricot.org/tlar_issues

Walker, K. (1995). Difficult clients and tutor dependency: Helping overly dependent clients become more independent writers. WLN, 19(8), 10–14. wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v19/19-8.pdf

Wells, J. (2016). Why we resist “leading the horse”: Required tutoring, RAD research, and our writing center ideals. Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 87–114. doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1802

Zuccarelli, J., Cunningham, N., Eils, C. G., Lee, A., & Cummiskey, K. (2022). Measuring the effect of writing center visits on student performance. Praxis, 19(3), 3–15. praxisuwc.com/193-zuccarelli-et-al