Ana Raquel Fialho Ferreira Campos, Midwestern State University of Paraná

João Tiago Gaspar Cozechen, Midwestern State University of Paraná

Elaine Pereira Lustosa, Midwestern State University of Paraná

Marcos Angel De Carvalho Eing, Midwestern State University of Paraná

Leonardo Schimiloski, Midwestern State University of Paraná

Abstract

Writing centers in Brazil emerge from an internationalization initiative that combines tutoring students on academic assignments and translating Portuguese articles written by faculty and graduate students into English. Thus, they arise from local needs and contexts. Three articles about writing centers in Brazil have been published, and only one mentioned student tutors’ views. This research aims to understand their views on being part of a Brazilian writing center while pursuing their majors and graduate courses. Through narratives, four participants have voiced challenges regarding dealing with texts from a diversity of fields, handling technical terms, and expressed varying degrees of self-confidence when working with a text written by an individual in a scholarly higher position. Regarding growth opportunities, the student tutors mentioned the development of soft skills and teamwork, improvement in performing reading and writing tasks in their undergraduate programs, and opportunities to increase their knowledge in other fields. The discussions presented in this paper contribute to tutors’ training and to other research on student tutors, as well as to the landscape of what writing centers do in the domain of international publishing.

Keywords: writing center, Brazil, student tutors, challenges, growth opportunities.

In the U.S., writing centers emerged from labs and clinics (Carino, 1995) and were a resource for college writing assistance for undergraduate students from the 1970s on. However, this is not a common scenario in Brazilian high schools or higher education institutions. Universities in Brazil originated in the 1900s, meaning that higher education is a relatively recent phenomenon. The Brazilian educational system was established based on a “banking model of education” (Freire, 1970/2007), a metaphor used to describe students as containers into which educators must deposit knowledge, reinforcing that knowledge came from outside. Students were not encouraged as creators of new ideas and little was done to develop students’ critical thinking and writing skills, bearing resemblance to the observations made by Mora (2022) on her Mexican context. In this regard, writing centers are not a national reality and are not found in high schools or universities, as most of the writing practice is devoted to the essay students need to write to be accepted in the university entrance exam (Cons & Rezende, 2024; Martinez, 2023). Brazilian undergraduate and graduate students struggle to meet the demands of higher education, accomplishing academic tasks such as an undergraduate thesis and writing for publication without the help or the culture of pursuing the assistance of a writing center.

Additionally, the pressure to publish internationally is an obstacle that faculty and graduate students must face, especially since high-impact journals publish in English and the Brazilian population is not bilingual. English language schools are profitable businesses in Brazil as compulsory education does not provide proper conditions for learning foreign languages. Thus, to cope with this demand, most graduate departments are applying part of their budgets to pay for translation and editing services (Martinez & Graf, 2016). Prof. Ron Martinez observed this scenario at the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR) and proposed the creation of the first Brazilian writing center – CAPA – Centro de Assessoria de Publicação Acadêmica (Academic Publishing Advisory Center) in 2016 to offer both translation and tutoring services (Martinez, 2023). Through this action, he aimed to apply resources inside the institution and provide academic and professional development to the students and faculty.

Following the creation of CAPA, seven other writing centers were established in the state universities of Paraná, Brazil in the second semester of 2021. The writing center at our university is one of them. Since its creation, our center has offered tutoring and translation services, with its staff comprised of a university lecturer as a coordinator and graduate and undergraduate students as tutors and translators. These student tutors use English as a second language and are majoring mainly in English Language and Literature; however, students from other areas are welcome and have been part of the center.

The increasing popularity of paid editorial services (Hartwood, 2019; Martinez, 2023) underscores the importance of writing centers offering sophisticated machine learning (ML) editing assistance, ensuring that all individuals may benefit from these services irrespective of financial circumstances. These two realities demonstrate that globalization and internationalization initiatives have influenced the tasks performed by some writing centers. In Brazil, student tutors are mainly involved in translation services from Portuguese to English, editing manuscripts in Portuguese and English, and tutoring undergraduate students in their academic tasks in Portuguese or in English. Performing these responsibilities involves challenges, and as a result, we want to explore the challenges and benefits of working as a tutor.

Though inspired by aspects of American models, writing centers in Brazil arise from local needs and contexts that display their distinct histories (Martinez, 2023). They emerge from an internationalization initiative that combines tutoring students on academic assignments and translating Portuguese articles written by faculty and graduate students into English (Cons & Rezende, 2024).

There are only three international publications about Brazilian writing centers: Martinez (2023), Cons and Rezende (2024), and Cons et al. (2025). Martinez (2023) explores the emergence and development of writing centers in Brazil, using the author’s experience as the founder of the Academic Publishing Advisory Center (CAPA) at the Federal University of Paraná. Cons and Rezende (2024) conducted their research at CAPA and focused on one particular consultation as a case study. Cons et al. (2025) discuss preliminary tutor impressions about Generative AI and evaluate how formal training on the use of Generative AI has impacted the translation and tutoring practices at CAPA. Even though these three articles present the Brazilian reality, none of them look at student tutors’ perspectives on working at a writing center in Brazil. International publications that focus on tutors (Thompson et al., 2009; Thonus, 2001, for example) have centered their research on the North American context. The current research presents the tutors’ voices on being part of a Brazilian writing center and advances the discussion about how writing centers in Brazil create situated practices with transnational applications (Mora, 2022).

To contribute to the landscape of what writing centers do (Jackson & McKinney, 2012), this article addresses the following questions: What are the challenges faced by these student tutors? To what extent do student tutors at one Brazilian writing center perceive their work at the center as beneficial for their individual growth?

Method

AI statement

Grammarly and DeepL Write were used to improve readability and language, not to replace any key researcher tasks. Grammarly was downloaded and used as an extension to google docs to proof-read the paper. On DeepL Write, we pasted excerpts of the text that we considered wordy or unclear.

Research Site

This research was conducted at a university writing center in the South of Brazil. This center is part of a state initiative that involves seven other writing centers that began their activities in the second semester of 2021. The selection of tutors is based on the student’s knowledge of English, Portuguese, and academic literacy. Student tutors are trained in academic writing, tutoring, and machine translation. They participate in regular meetings with peers and coordination, receive instruction, share their work and challenges, and discuss the work of the center through readings such as Swales (2000), Graff and Birkenstein (2009), Nelson and Schunn (2009), and Hyland (2016), among others.

Our university writing center provides two different one-on-one sessions. The first one is a tutoring session inspired by the American model, and the second one is part of the translation process pushed by internationalization demands at higher education institutions (Martinez, 2023).

Writing center sessions happen online, mainly through Google Meet, as the center holds student tutors from different campuses and cities, demanding the use of the online environment for all the tasks. In translation service meetings, the student tutors have previous meetings with the authors who submitted their texts for translation. In this session, called assessorias (an advisory meeting), the member of the writing center in charge of the text has the opportunity to clarify ambiguous excerpts, and confirm understandings.

Even though the writing center services are available to the university community, they are not part of the Brazilian academic culture, and we frequently meet students and faculty who do not know about our services. Initiatives to promote the center involve meeting with heads of departments and graduate courses, and creating the center’s website [1] and Instagram page[2] that feature contributions from the student tutors. Following Reichelt et al. (2013) and May (2022), we use social media to popularize the center, reach out to students and faculty, and create a community, either within the writing center or on campus.

Our tutors are also required to participate in other initiatives and academic events, such as preparing presentations about the center, leading workshops at undergraduate events, translating institutional material, training new student tutors, and writing for publication as a team. As Jackson and Mckinney (2012) affirmed, writing center professionals engage in many activities beyond the work with the academic texts, in our case, they are also translators.

Data Collection Methods

To understand the views on being part of a writing center in Brazil, narratives were written by four student tutors who have been part of the center since its beginning in 2021. According to Riessman (2008), narratives can be found in a variety of sources in the human sciences, including interviews, organizational documents, discussions, diaries, artwork, and autobiographies. The term “narrative” can apply to both full life experiences and a research participant’s response to a particular topic. The four student tutors were invited to write narratives about their experience, their expectations before and after working at the center, perceptions of personal development, and any other significant experiences they would like to comment on. These narratives were written remotely and the deadline to upload them in a shared file was 30 days. There were no length requirements.

A potential limitation of this study is that the narratives were read by the tutors themselves and the coordinator. Consequently, any negative comments regarding peers, administration, or the center in general may have been suppressed.

Participants’ Demographic Information

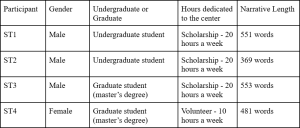

Currently, seven student tutors are working at the center and four of them were invited to participate in this study. These four students were chosen because they have participated in the center’s activities since its beginning in 2021. They are all from the English Language and Literature program: two are undergraduate students (ST1 and ST2) and two are pursuing their master’s degree (ST3 and ST4). Three of the students receive scholarships for working at the writing center and one is a volunteer who also works at a language center. In keeping with the culture of student tutors’ active participation, they are also the writers of this article, collectively with the coordinator. Table 1 summarizes their information.

Table 1

Student tutors’ information

Data Analysis

In this qualitative research, we applied Content Analysis (Mayring, 2000; Rose et al., 2020) to interpret the data and employed relational analysis to allow themes to emerge from identified patterns. The four texts were uploaded to Google Drive and shared among the four students and the coordinator. The four narratives were analyzed through an initial open coding phase followed by selective coding. We have adapted Mayring’s (2000) steps to our data analysis, transitioning from the research questions into a tentative and feedback process to define categories from the data. Subsequently, the categories were revised and consolidated into main categories. The authors investigated the connections among the data and wrote the codes and comments in the margins of the narratives. These comments also served as a means of communication among the authors throughout the research process, as they discussed their findings and the connections within the data. Each member of the research team was responsible for reading and coding the four narratives. A meeting was convened to discuss the data and the elements that emerged from the coding process.

Findings

The subsequent discussion will be divided into two main categories, challenges and growth.

Challenges

Reviewing Papers Outside the Tutor’s Immediate Scope of Knowledge

One of the challenges raised by three of the four participants is the variety of fields of study they work with. ST2 highlighted this breadth of areas as the greatest difficulty in working at the writing center. As previously stated, most student tutors are from the English Language and Literature program, which is primarily focused on teaching. Consequently, when working with subjects such as Exact Sciences, they may encounter challenges in comprehending certain concepts and terminology. Working with texts from different fields is a task mostly performed in our center’s translation service, receiving texts from areas such as Agronomy, Nutrition, English, Geography, Physiotherapy, Pharmacy, and Environmental Engineering, to name a few.

Regarding the challenge of varied fields, ST3 wrote:

I would say that sometimes I come across texts that are difficult to understand because they are from areas that are very different from my own […] Sometimes, I’m not sure if what I come across is a writing error or something specific that I didn’t know about from the author’s area of expertise.

The various fields of study generate specific technical terminology that presents significant challenges for translators. At times, it can be difficult to identify the most common and comprehensible expressions within a particular field, requiring consultation of additional academic sources to verify the terminology. In this context, ST4 wrote:

Experiencing the reality that working with a text on a subject I was unfamiliar with was a hard task […] Dealing with technical terms during a translation sometimes means doing research for a good time before you can confidently translate a specific segment.

The research process required to translate a specific segment was part of the tutors’ training when they learned solid ways of confirming the technical terms from each field through Google Scholar, ensuring the presence of the term in the reference texts, and reading other materials from the same field. This practice also reflects the local needs and skills necessary in a Brazilian writing center (Martinez, 2023).

Reading texts from different areas is indeed a challenge, as it demands a greater effort to understand the research conducted in a field that is not yours. The margins of the manuscripts serve as a means of communication between the tutors. They share doubts and knowledge through these comments, relying on one another to increase their expertise, reflecting collective learning. This exposure to academic texts displays a positive outcome related to academic literacy (Marinho, 2010), which will be presented in the Growth section of this paper.

Tutors’ Levels of Self-Confidence

A challenge that emerged from one of the narratives is the variation in the student tutors’ self-confidence, where impostor syndrome (Bernatt, 2008) is mentioned not as a constant feeling, but as a process that can be overcome. ST4 stated that “trying to overcome my impostor syndrome is a process still in progress. I believe that with every text reviewed, every translation concluded, and every meeting attended I feel more comfortable and confident with my work (ST4)”. The other student tutors did not mention impostor syndrome in their narratives.

It is noteworthy to observe that undertaking writing center tasks has contributed to enhancing the tutor’s sense of confidence and has facilitated a deeper understanding of her role in the publication process. She emphasized that “knowing that my work, effort, and knowledge actively contributed to the publication of research proves that I can actually accomplish great things doing this work and that I should be proud of it” (ST4). She began to plow through the impostor syndrome and understand that she was capable of being a translator and an academic tutor while performing her tasks at the center.

The fluctuation of self-confidence may be noticed in another excerpt of ST4, where she discusses the challenges of working on manuscripts from doctoral students or professors as an undergraduate or master’s student tutor. She questions herself on this matter, despite having received training, discussing the text with peers, and receiving supervision by the center’s coordination. ST4 says:

Knowing that the person was a PhD made me intimidated, but upon meeting this author and conducting the meeting I became more confident in my place and managed to ask and answer the necessary questions. This not only helped me to grow more self-confident but also changed my perspective to an optimistic future in this academic field. (ST4)

It is interesting to observe how the student tutor manages her initial feelings and does not allow them to influence her work. Initially, she expressed concerns regarding the advisory meeting, as she was uncertain about its progression. The differences in titles make the student tutors uneasy since they are unable to predict how PhD authors will respond to their suggestions and recommendations concerning the papers. At times, suggestions of a more advanced nature are put forward, which may not be accepted by the authors.

Growth

Tutors’ Sense of Teamwork and Collaboration

It is noteworthy that the four participants referenced the concept of “teamwork” in their respective narratives. They perceive teamwork to be of paramount importance at every stage of the project, as the participants collaborate to ensure the quality of their work. In one participant’s voice: “to ensure the best quality, translations and revisions are carried out in teams, usually of two to four participants, where each contributes with their expertise and one person’s strengths cover the other’s weaknesses” (ST1). When translating or editing a text, the tutors will share doubts and difficulties with their colleagues, who provide advice on improving the article and offer their translation and writing skills. For ST3, “working with colleagues helped me to see elements that I couldn’t perceive on my own and that I learned through contact with them.” The collaborative nature of the center provided the opportunity for the student tutors to learn from one another, which reflects the mutual engagement of communities of practice (Wenger, 1998) as they make meaningful connections with the knowledge and contributions of others. The concept of community of practice applied to writing centers (Geller et al., 2007; Mora, 2022) is also pertinent to our Brazilian context, as it is a collection of people with a common concern, set of issues, or interest in a subject who continue to connect and expand their knowledge and competence in that field.

Importance of Advisory Meetings

Three student tutors cited the advisory meetings as a growth element in their narratives. For ST2, they are opportunities to increase knowledge in other fields. He conceptualizes them as a pivotal component of the translation process and as a means of problem resolution. Following the initial reading, the student tutors document any concerns they have regarding the article. Subsequently, during the advisory meeting, they seek clarification from the authors on these concerns. This student tutor drew parallels with a “round table” in which the authors and tutors engage in a similar position to discuss the text. According to him, these meetings also “give [him] a great opportunity to get to know the field of study being carried out in more depth” and this helps him to understand the topic of study and consequently perform a good job.

Additionally, according to ST4 and ST3, talking to the authors about their texts in the advisory meetings improved their interpersonal skills. The work at the writing center provided tutors with opportunities to practice giving constructive feedback, asking for clarification, and giving suggestions in an academic realm (Nelson & Schunn, 2009).

Writing Center Encouraging Learning within Tutors

The learning outcomes were mentioned in three narratives. They are strengthened by the fact that English is not the tutors’ mother tongue. Besides acquiring knowledge of Brazilian writing guidelines, the tutors also study American guidelines, such as APA. They have also learned about the requirements for publishing in Brazilian journals as well as international ones. They could observe the difference in writing styles in Portuguese and in English. In addition, vocabulary is enhanced in both languages.

About this matter, ST3 stated that he “had acquired a substantial number of expressions, acronyms, and technical terms thanks to reading different articles in different fields”. For ST1, “understanding the structures that constitute a good text is important, and knowing the guidelines is essential. However, these things take time and it was common for me to spend long hours researching and reading different materials every night.”

ST4 also highlighted the writing center as a place for learning. She stated that, as time went by, she realized she “was learning so much more than initially expected” and that she “still learns something new whenever faced with a paper to work with” (ST4), a statement that reflects another characteristic of a community of practice (Geller et al., 2007; Mora, 2022). Comments like the ones above stimulate more intentional actions to promote a learning culture at the center. This endemic learning culture creates our situated practice (Mora, 2022) and deepens our understanding of daily tasks.

Tutors’ Academic Growth

The four participants raised the topic of academic growth in their narratives. ST1 emphasized that his participation in other academic projects, such as undergraduate research or extension, has been facilitated since he began working at the center. He noticed an improvement in performing essential tasks in undergraduate courses, such as reading theoretical material, synthesizing, and discussing it.

The truth is that being in daily contact with articles has had a huge impact on my academic performance. Since I joined the writing center, I’ve never had any problems with essays or parallel projects such as extension and undergraduate research. The “trickier” parts of reading the theoretical material, synthesizing, and discussing it ended up flowing very well. (ST1)

It is worth questioning how much exposure would be necessary and how long it would take to create a positive impact like the ones mentioned by ST1. He added that “the regular contact with academic articles had a significant impact on my academic performance” (ST1). The regular contact mentioned by the tutor is characterized by careful study of academic genres, the structure of an article (Swales, 2000), Brazilian and American style guidelines, and attentive readings performed throughout their work.

For ST4, confronting her impostor syndrome led to positive personal development. In her words, the process resulted in a determination characterized by enhanced study habits and a more diligent approach to professional obligations. She said:

Trying to overcome my impostor syndrome is a process still in progress. […] Sometimes this fear helps me to study more and improve my work. I also believe it makes me humble and reminds me that it is important to keep researching and trying to learn more to contribute to the work done at the writing center. (ST4)

It is worth noticing how the same activity, advisory meetings, have different effects on the tutors. For some, they are a source of uneasiness, a place to test their self-confidence, while for others, the meetings are opportunities to improve their soft skills and enhance their study habits. These effects must be approached in the training sessions to better equip the tutors for their future tasks. Within this paradigm, the center coordinator may talk about the benefits and opportunities that the advisory meeting holds, preventing the eyes of the tutors from falling mainly onto the challenging aspects of conducting the one-on-one meeting.

Tutors’ Translation Work

A final growth opportunity identified in the four narratives is related to the translation work. This task provides an enlargement of professional opportunities for its participants since, at our university, the English Language and Literature Program (Letras) is designed for teaching, with no translation courses incorporated into the four-year program (Projeto Pedagógico, 2020). This matter was raised by ST3 as he described the center as an opportunity for those who want to work with translation. He said that “the work at the center appears as a gateway for all academics who, in addition to teaching, want more opportunities, both for employment and personal growth” (ST3). Thus, the writing center’s importance goes beyond tutoring; it also emerges as a place to learn and achieve expertise not only in academic writing but also in translation.

Therefore, the center is a place of collective benefit. For the authors, who receive support for their scientific work or have their articles translated into English, and for the tutors, who develop important skills through their work at the center. On that note, ST4 stated that being able to be part of the center changed her life for the better, as her progress encompassed her peers and the university community. In her words, “I not only improved my academic skills, but I also helped others to grow with me.”

Concluding Remarks

This research discussed student tutors’ perspectives on working at a writing center in Brazil based on the analysis of their narratives. The participants voiced challenges and growth opportunities relevant to tutor training and development. The challenges rest on dealing with texts from a diversity of fields, working with technical terms, and having a variation of self-confidence when working with a text written by an individual in a higher scholarly position. Regarding growth opportunities, the student tutors mentioned academic growth, teamwork, the development of soft skills, and professional opportunities in technical translation. The fact that Brazilian student tutors are also translators demonstrates the different skills and tasks performed by tutors outside the United States. It also reflects the participation of the writing centers in fair access to publishing and internationalization initiatives (Kyle, 2018).

The center exhibits the characteristics of a community of practice (Wenger, 1998), akin to other writing centers documented by Geller et al. (2007). The concerns of one member become collective matters, resulting in mutual engagement and shared learning. This collective learning is particularly welcome, as the development of student tutors has been a fundamental principle since Prof. Ron Martinez began writing centers in Brazil, fostering academic identities both inside and outside the center (Martinez, 2023).

Further research could delve into analyzing the perspectives of tutors from other Brazilian writing centers, as they share tasks that involve internationalization initiatives, such as offering translation services. A study of this kind, with the involvement of tutors from different centers, would be a step forward in the understanding of the Brazilian context. The issues of self-confidence presented in this paper demand further investigation to provide alternatives to the process of self-assurance, analyzing helpful methods employed by tutors during advisory sessions. The data presented in this research contributes to the selection of content for training sessions in Brazil. The coordinators may find the information useful to facilitate discussions on subjects such as opportunities in advisory meetings, collaborative work, ongoing learning processes, and future professional opportunities. We expect that the discussions presented in this paper contribute to tutors’ training, and to other research on student tutors’ participation, as well as to the landscape of what writing centers do in the domain of international publishing, as it is valuable to read about what writing centers outside the U.S. do to assist authors, especially the ones who are in contexts where English is a foreign language.

References

Bernat, E. (2008). Towards a pedagogy of empowerment: The case of “impostor syndrome” among pre-service non-native speaker teachers in TESO. ELTED, 11(1), 1–8.

CAPA. (n.d). Sobre o CAPA – o primeiro ‘writing center’ do Brasil. http://www.capa.ufpr.br/portal/about/

Carino, P. (1995). Early writing centers: Toward a history. The Writing Center Journal, 15(2), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1279

Cons, T. R., and Rezende, C., R., A. (2024). Brazil’s First Writing Center: Promoting Global Access and Enacting Local Change. The Peer Review. Issue 8.

Cons, T. R., Mattos Brahim, A. C. S., Pedra, N. T. S., and Maeso, P. B. M., (2025). Tutor’s Perceptions on AI Tools and Translation at CAPA-UFPR, the first Brazilian Writing Center. The Peer Review. Issue 9.2.

Freire, P. (2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans; New rev. 20th-Anniversary ed.). Continuum. (Original work published 1970).

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., and Boquet, E. H. (2007). Everyday writing center: A community of practice. University Press of Colorado.

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., and Durst, R. K. (2009). They say, I say: the moves that matter in academic writing (1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Hartwood, N. (2019). ‘I have to hold myself back from getting into all that’: Investigating ethical issues associated with the proofreading of student writing. Journal of Academic Ethics, 17(1), 17-49.

Hyland, K. (2016). Academic publishing and the myth of linguistic injustice. Journal of Second Language Writing, 31, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.01.005

Jackson, R., and McKinney, G. J. (2012). Beyond Tutoring: Mapping The Invisible Landscape of Writing Center Work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 9(1), 1–11. Retrieved from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/62108/Jackson_McKinney%209.1RaisingtheInstitutionalProfileofWritingCenterWork-10.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Kyle, B. R. (2018). Merging tutoring and editing in a Chinese graduate writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 15(3), 23-35.

Marinho, M. (2010). A escrita nas práticas de letramento acadêmico. Revista brasileira de linguística aplicada, 10, 363-386. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982010000200005

Martinez, R., and Graf, K. (2016). Thesis Supervisors as Literacy Brokers in Brazil. Publications, 4(3). 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications4030026

Martinez, R. (2023). The Idea of a Writing Center in Brazil: A Different Beat. The Writing Center Journal, 41(3), 133–142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27275945

May, A. M. (2022). On Networking the Writing Center: Social Media Usage and Non-Usage. Writing Center Journal, 40(2), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1022

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 10. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089

Mora, A. V. (2022). Crafting a Practice of Our Own: A Writing Center in Mexico. Connecting Writing Centers Across Borders. https://wlnconnect.org/2022/11/29/crafting-a-practice-of-our-own-a-writing-center-in-mexico/

Nelson, M., M. & Schunn, C. D. (2009). The nature of feedback: How different types of feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science, 37(4): 375-401

Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Graduação em Letras (2020) XXXXX – Midwestern State University of Paraná. Retrieved from https://sgu.XXXXXXXXX.br/pcatooficiais/imprimir/4E616154

Reichelt, M., Salski, Ł., Andres, J., Lowczowski, E., Majchrzak, O., Molenda, M., and Wiśniewska-Steciuk, E. (2013). “A table and two chairs”: Starting a writing center in Łódź, Poland. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22(3), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2013.03.002

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

Rose, H., McKinley, J., & Briggs Baffoe-Djan, J. (2020). Data collection research methods in applied linguistics. Bloomsbury.

Swales, J., and Feak, C. B. (2000). English in Today’s Research World: A Writing Guide. University of Michigan Press.

Thonus, T. (2001). Triangulation in the Writing Center: Tutor, Tutee, and Instructor Perceptions of the Tutor’s Role. The Writing Center Journal, 22(1), 59–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442136

Thompson, I., Whyte, A., Shannon, D., Muse, A., Miller, K., Chappell, M., and Whigham, A. (2009). Examining Our Lore: A Survey of Students’ and Tutors’ Satisfaction with Writing Center Conferences. The Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 78–105. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43442315

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932