Ghada Seifeddine, Purdue University

Abstract

In the past ten years, scholarship has increasingly directed attention to the intersections between disability studies and writing center work, emphasizing the importance of multimodality, Universal Design Learning (UDL), and academic support for students with disabilities. Though the literature on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in writing spaces highlights the personal narratives of student writers, tutors, and administrators (see for example, Garbus, 2017; Stark & Wilson, 2017; Zmudka, 2018), empirically-based research on the topic remains rare. This empirical study looks at how a seemingly invisible disability, like ADHD, affects tutors and clients in the writing center. Results from this study’s survey of existing tutors and clients, in conjunction with semi-structured interviews, revealed tutors and clients’ need for more conversations around neurodivergence, as well as better support and equity in the writing center and in other institutional organizations and academic resources on campus. Participants also highlighted the need to foster a culture of understanding and mutual listening rather than relying on disclosure, to provide accessible modes of tutoring for clients, and to include training around disability literacy in tutor education. Overall, this paper unwraps the often hidden stories of tutors and clients with ADHD and provides ways to (re)think neurodivergence in writing center work.

Keywords: Tutoring, writing, process, disability, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, neurodivergence, accessibility, support

As an international graduate tutor in my writing center, receiving my Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) diagnosis as an adult made me highly cognizant of the issues that neurodivergent [1] students like myself face in academic spaces, including how to navigate our classes, maneuver teaching and tutoring, and educate ourselves and others on the reality of disability (in)justice. Almost three years ago, I encountered a client who disclosed having ADHD in the middle of our face-to-face session. The first-time client had a poster on mental health concerns for her psychology course. She expressed needing help to organize her poster and make sure its content is clear. At one point in the session, she disclosed having ADHD, to which I blurted, “I have ADHD too!” I noticed her demeanor change, as she eased up in her chair. It was my first time disclosing that I have ADHD. In retrospect, my self-disclosure served as an act of awareness, understanding, and reassurance. I also wanted to normalize discussions surrounding disability in the session because it pushed us towards an open and honest conversation about what I could do to adjust my tutoring approach and best support her as a writer. Our overall exchange prompted me to consider what happens when disability comes into the equation in a writing center context.

In the past ten years, scholarship has highlighted the intersections between disability studies and writing center work. Much of this work emphasizes the need to conduct more studies on disabilities and neurodivergence in the writing center (Babcock, 2015; Babcock & Daniels, 2017; Daniels et al., 2017; Dembsey, 2020; Hitt, 2012, 2021; Kleinfeld, 2018; Rinaldi, 2015). In particular, Babcock (2015) urges writing center practitioners to produce more empirically-oriented studies on less visible disabilities, including ADHD, one of the most common disabilities among college students. More importantly, this study challenges the problematic rhetorics of disability that show up in our writing center communities, as the writing center is one facet of how an institution functions. Hitt (2021) points out that dominant discourses of disability in writing center work are often concerned with diagnosis and accommodation, which coincides with a remediation model that treats disabilities as problems to diagnose and overcome. Dembsey (2020) sheds light on the discrimination that disabled individuals face in writing center instruction and environment, like questioning whether disabled writers need support, perceiving disability as something to “fix” in a writing center context, and placing burden and judgment on disabled writers and tutors who self-disclose.

In response to the positioning of disability as deficit in the writing center, writing center practitioners have challenged this notion and taken the lead on rethinking the disability discourse (for example, Anglesey & McBride, 2019; Degner et al., 2015). This notion coincides with Denny’s (2005) call to think of writing centers as liminal spaces that can disrupt the norm and “destabilize conventional wisdom of what we do and who we are” (p. 56). In the same spirit, this study aims to challenge the problematic discourses that linger in writing center research on disability. Its goal is to also envision the writing center as a rebellious space that can amplify the voices of neurodivergent tutors and clients, promote a culture of intentional listening and accessibility, and adapt to the needs of its diverse tutors and clients.

In this empirical study, I focus on the experiences of neurodivergent tutors and clients with ADHD in the writing center space. Using an initial brief survey, followed by semi-structured interviews with tutors and clients with ADHD, I explore how clients and tutors with ADHD recount their experiences in past tutoring sessions and how they describe their writing process(es). I also discuss how clients and tutors with ADHD can be supported in the writing center.

Literature Overview

To recognize the ways in which the rhetoric of disability shapes how we approach our work in a local context like that of a writing center, we must acknowledge the larger cultural problems surrounding disability in higher education. Disabilities have long been used to ostracize students who are forced to face the disabling challenge of misconceptions about how they learn and present themselves in their environment (Dolmage, 2017; Hitt, 2021; Price, 2011). Nestled within higher education, the writing center can serve as a liminal space where misconceptions surrounding disability can be continuously challenged and unlearned.

Disability rhetorician Dolmage (2017) argues that we need to construct the concept of disability as very real and shared. Oftentimes, students with (in)visible disabilities are stigmatized; they are “already routinely and systematically constructed as faking it, jumping a queue, or asking for an advantage” (Dolmage, 2017, p. 10). As educators, Dolmage urges us to recognize that ableism, which he defines as a set of ideas and beliefs that value physical, mental, and social ability, renders able-bodiedness as the norm and represents disability as deviance from that norm. The myth of the normal body and typical mind positions students with disabilities as a problem to eradicate or fix. Dolmage (2017) then states that higher education still upholds this myth, emphasizing ability while pathologizing intellectual and/or physical weakness. Similarly, Price (2011) affirms that the “problem” of disability continues to permeate and affect how we label certain students (and professionals) in academia as deviant and in need of remedy. She explains that while disability discourse sheds light on individual experience, this discourse is also a political and social issue that requires more attention.

There is immense exigence in reconstructing how disability is culturally perceived. Kerschbaum et al. (2017) share a similar sentiment in their work on disability in higher education. They explain that disability is a crucial part of diversity, which is multifaceted, intersectional, and dynamic. Diversity work requires institutional change, and the same can be said when we engage in conversation about disability in higher education: “We cannot talk about diversity and keep doing things the way we have always done them” (Kerschbaum et al., 2017, p. 4). Hence, we must continue to negotiate how disability comes up in academic spaces like the writing center and consider how institutional policies and pedagogies can be enabling or disabling to its student body.

The problematic understanding of disability as deficit has funneled into writing center communities. Dembsey (2020) argues that ableism has and continues to perpetuate in writing center discourse. For instance, many writing centers rely on diagnosis to identify and tailor their tutoring approaches. As Dembsey (2020) remarks, this dependence on diagnosis in a writing center context is ableist because it reaffirms the binary thinking surrounding disability and removes efforts to reflect on more inclusive writing center practices. Hitt (2021) also highlights the lack of knowledge and familiarity on part of writing centers when working with disabled writers, which is then made worse when writing center staff are pressured to serve as disability experts. This positioning leaves little to no room for student writers to self-advocate for their own writing needs and offer their own input on what will improve their learning. Rinaldi (2015) lays out a similar argument, noting the disconnect between how we teach about collaboration and agency and how we approach disability in the writing center. Writing centers teach tutors to empower their students through non-directive instruction and empathic listening; however, when it is a writer with a disability, their disability is viewed as a defect. It is important, therefore, for writing centers to continuously and consistently assess their role in challenging the dominant notion of disability that permeates in higher education.

Writing center studies have discussed the need to reconfigure the writing center as a space that is aware of the neurodiverse pool of students that walk into sessions and listens more to their learning needs. In their study on tutors struggling with invisible disabilities, Degner et al. (2015) found that writing center administrators should reflect more on what they are doing to create a supportive community and establish safe spaces to communicate about issues of mental health and disabilities. They acknowledge that doing so is “a non-linear, ongoing process of change and revision, a process [they] encourage all centers to participate in regularly” (Degner et al., 2015, p. 34). Anglesey and McBride (2019) examine the impact of active listening as an inclusive practice that makes the writing center “more welcoming—more inclusive—of students with disabilities” (para. 4). They view listening as kairotic and complex yet instrumental for tutors to tune in on the diverse student experiences. These studies reflect the importance of fostering a writing center culture that engages in conversations about disability and neurodivergence as a step towards empowering its community.

In relation to fostering an accessible culture, disability and disclosure issues have been addressed. Disability disclosures are dynamic and depend on the circumstances and context within which they are sought. While it might be argued that such disclosures can be seen as liberating, capable of promoting more transparent and welcoming environments in higher education, Kerschbaum et al. highlight that disclosures are complex and nuanced: “disabled identities always intersect with other identities and that the risk-taking that accompanies disclosure is not experienced equally or in the same ways by all people” (2017, p. 2). To extend this argument, Hitt (2021) invites us to recognize that disclosure can be harmful when used as a measure to diagnose; the point of listening to student writers is not to diagnose, but rather to initiate “accessible support systems” (Hitt, 2021, p. 31).

In terms of pedagogical support in the writing center, Babcock and Daniels (2017) highlight the importance of Universal Design Learning (UDL) as a useful pedagogical move when working with neurodivergent learners. They refer to Hitt’s (2012) advocacy for attending to the needs of different learners by employing multimodal toolkits. In her subsequent work, Hitt (2021) calls for a transformational move from accommodating students to providing them with access. She explains that accommodations, while good-intentioned, keep oppressive structures in place because students with disabilities are having to fit into built-in spaces and carry the burden of disclosing their disability. Hitt (2021) encourages teachers of writing and tutors to abandon the accommodation model and think of how they could invite students to come over, as opposed to leaving it up to students to “overcome” their disability. Multimodality can be applied in different ways, as can be seen in Kleinfeld (2018) and Cecil-Lemkin and Johnson (2021) works. In efforts to make their writing center more inclusive, Kleinfeld (2018) takes deliberate steps to practice UDL, like hiring a diversity of student tutors, changing tutoring practices to discuss learning modalities, and remodeling the writing center space with feedback from its community. Cecil-Lemkin and Johnson (2021), on the other hand, share their process of developing a multimodal toolkit for their writing center for tutors to learn more about disability studies.

From an administrative stance, Daniels et al. (2015) reflect on the policies of inclusion when it comes to supporting students with disabilities in the writing center. They emphasize that an inclusive approach is futile without writing centers working at the forefront to implement pedagogical practices that meet student needs. Dembsey (2020) reminds writing center professionals that “access is a shared responsibility,” and that if we are to move from an ableist to an accessible culture, we need to center the narratives of disabled individuals, like tutors and clients in tutor education. Tutor training, in this sense, is vital to opening up conversations about accessibility as part and parcel to how we do our writing center work. This coincides with Elston et al.’s (2022) research on “taking our cues about access needs from those seeking access,” which requires us to invoke dialogue with disabled tutors and writers for they are our greatest source on what makes access happen.

More specific to what this article explores, studies on ADHD among writers and consultants have focused on concerns of disclosure and stigma (Garbus, 2015; Stark & Wilson, 2016) or have centered personal experiences of tutors with ADHD, as in Zmudka (2016). To expand on that research, I aim to consider how a seemingly invisible and often unmarked disability, like ADHD, affects tutors and clients in the writing center. Batt (2018) writes that “we have more work to do,” and to do so, “we can start by encouraging more studies about and by the neurodivergent workers in our midst” (Batt, 2018, para. 13). This study is my attempt to contribute to the ongoing scholarship on disability in writing center work, challenging the categorizing of disability into a false binary of normal and subnormal by centering the experiences of student writers and tutors with ADHD, both of whom are co-collaborators in a session and members of writing center spaces. This study also underscores how “disability can instead be a rich site of invention in writing center studies” (Elston et al., 2022, para. 29), specifically when it comes to the ways in which writing centers can provide support to its neurodivergent community and foster a culture of understanding and empowerment.

Methodology

Participants and Methods

The mixed-methods study consisted of sending out a brief survey (see Appendix B) to tutors and clients at a writing center at a large land-grant university in the Midwest, followed by a set of semi-structured interviews (see Appendix C). Degner et al.’s (2015) survey focused on soliciting information from writing center tutors about their mental health issues, and Stark and Wilson’s (2016) interviews with tutors and clients with ADHD guided the content and structure of my methods.

After acquiring approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) [2] and receiving permission to access my writing center’s tutor and client contact lists, I sent out a survey to fellow tutors and clients. The survey, designed on Qualtrics, featured ten survey questions and solicited responses on the topic of writing and tutoring with ADHD. Specifically, the survey collected information about the tutors and clients’ understanding of ADHD and ways in which writers with ADHD can be supported. Of the 50 tutors who were sent the survey, 17 tutors responded, and eight of them disclosed that they have ADHD. Of the 1100 clients who were sent the survey, 56 clients responded, and 23 clients disclosed their ADHD. For the scope of this project, the most important aspect of the survey answers were tutors and clients’ open-ended responses on successful strategies their writing center and tutors can do, as well as the kinds of support that their writing center can provide to tutors and clients with ADHD.

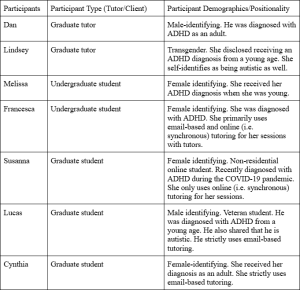

The survey’s last question asked tutors and clients with ADHD if they were interested in being interviewed on Zoom, which helped solicit potential participants [3] who were willing to volunteer for an interview. I interviewed two tutors and five clients about their ADHD diagnosis [4], their writing center experiences with ADHD, effective approaches in consultations, and suggestions on the kind of support they wanted. I also asked them about their writing experiences as it might connect to having ADHD. The interviews with participants took between 30 to 40 minutes. Table 1 (see Appendix A) lists participants’ pseudonyms, relevant demographics, and positionalities, which I retrieved from my conversation with participants in the interviews. Participants’ real names were removed and replaced with their pseudonyms to remove direct identifiers in the transcription and analysis portions.

Coding and Data Analysis

From the survey, I divided responses into two categories, one for tutors and another for clients, and only used data from respondents who either disclosed or self-identified as having ADHD. The most important aspect of the survey answers were tutors and clients’ suggestions on successful strategies their writing center and tutors can do, as well as the kinds of support that their writing center can provide to each of their tutors and clients.

From the interviews, I went through two cycles of coding to detect emerging patterns in my data, using Saldaña’s (2021) approach in The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers and Grutsch McKinney’s (2016) outlined strategies for managing qualitative data. After doing a first and second reading of the transcripts to familiarize myself with the data and putting them in a similar format, I used NVivo software to upload the transcripts and isolate the most relevant data to my research questions. With the reduced data, I started my first cycle of coding, which included analyzing emergent codes from my dataset. I then selected the emergent codes that were showing up most frequently in the transcript data to further synthesize them in the second cycle of coding. In the second coding pass, I narrowed my focus to the codes that were most important to my research focus and grouped codes that revolved around the same topic. For example, when participants discussed their writing process, their writing strengths, and their writing struggles, I grouped them under “writing/literacy” to identify similarly coded data. I also took analytic memos to write about possible connections across participants and their interview data. When it came to tutoring approaches, for instance, I wrote down a list of strategies that participants thought helped clients with writing (such as tapping into feedback and comments, approaching the session with clear communications, discussing accommodations, considering how accessibility affects the session, and recognizing efforts by the tutor to be fully present, patient, and understanding in a session).

To connect the interview data with the survey data, I decided to extract survey responses that were most meaningful to answering the research questions. The quantitative portion of the survey was less helpful than I thought it would be and did not adequately highlight the individual voices of writing consultants. Therefore, for the sake of convenience and research scope, I solely focused on participants’ suggestions in the open-ended option on successful strategies in tutoring sessions as well as participants’ opinions on support from their writing center. This helped put the survey data and interview data into conversation with each other.

Results

Writing Center Experiences of Tutors and Clients

In the interviews, tutors and clients were asked about their experiences as it relates to their ADHD in the writing center. Some tutors and clients compared their tutoring sessions in multiple writing centers they have attended or worked at, respectively. While tutors shared their thoughts about the intersectionality of their neurodivergence, gender, and/or profession, clients talked about the importance of adopting a culture of listening, understanding, and accessibility in their writing center. As part of their experiences, tutors and clients also described moments they decided to (not) disclose that they had ADHD in tutoring sessions.

Tutor Experiences: Intersection of Neurodivergence, Gender, and Profession

First, my interviews with the two tutors revealed conversations about their multifaceted identities in the lab. To the tutors, neurodivergence constitutes one aspect of who they are. Lindsey confessed that she had to adapt to tutoring and be honest about how she operates as a neurodivergent tutor:

“I had pretty bad sessions when I first started because of my ADHD, so now I try to be honest about my limitations. For some people, it is harder to be open, but to me, it’s got something to do with the fact that I am trans too. I want to get it all out there… You know I am trans as soon as you see me. I feel that way about ADHD and autism too. It really helps to say upfront how I have this thing, and I need to do things in a certain way because it will be more helpful for the session.”

While Lindsey explains that her gender identity is overtly visible, her ADHD is not. To her, transparency in tutoring interactions is a productive approach to sessions. Dan reflected on his tutoring experience in relation to his professional role at the lab. He recounted working with many students on professional development materials. He found it most important to listen to clients and help them connect their values and goals in job materials that his clients might have a hard time figuring out on their own. While Dan mentioned that he might not disclose that he has ADHD in a session, especially with a first-time client, he would much rather listen closely to what his clients need and help them hone their writing skills. Overall, the tutor’s identity in the center is not homogenous, and while their ADHD might be invisible, unless they choose to disclose it, their ADHD affects how they perceive their role and other facets of their identity.

Client Experiences: A Culture of Listening, Understanding, and Accessibility in the Center

Clients were also asked to describe their experiences coming to the writing center, specifically recalling any memorable tutoring sessions considered to be successful and/or frustrating. Across all five client interviews, I noticed that clients focused on their communication with their tutor(s) and the kind of rapport built within consultations. All five clients with ADHD expressed how their experiences in their current writing center helped them grow as writers in a comfortable low-stakes environment. Some clients remarked that the more successful consultations took place when their tutor provided clear feedback with follow-up questions and accessible options to keep the communication going. The following response is an example that highlights Melissa’s experience:

“I tell my friends with ADHD to go to the [writing center] because, I promise, the tutors do it in a way that is not overwhelming. They do not make you feel dumb, which is an experience I have definitely had during tutoring situations [in high school] where I felt judged, and that makes you never want to go back to the tutor. I wish more people utilized the [writing center], but I understand why some people don’t.”

Melissa went on to explain that her tutors—which were mainly teachers—in high school were not approachable; they were not patient enough to hear her out when she wanted to explain her thoughts. Her high school tutors also rushed her, which is why she thinks having hour-long sessions at her current writing center gave her time to break everything down and think more clearly in her writing. Her explanation shows that her current writing center provided a judgment-free zone where she gets to openly communicate her needs, away from any shame surrounding her disability.

Another participant, Francesca, mentioned a similar story. Compared to her current writing center’s understanding culture, her teachers in her high school’s writing center were not helpful. She goes on to describe her first time in her university writing center:

“I went to the [writing center] for the first time last semester because it was one of the first times I had a writing-intensive class, and I went in and immediately clicked with the tutor…. I came in with all these sheets of paper with post-it notes on them. She [the tutor] then helped me reverse outline and organize my ideas.”

Francesca, however, admitted that some of her friends with ADHD did not utilize the writing center, and she explained that, “It is intimidating…. It feels icky almost, for a lack of better terms, to sit there and explain to someone who is neurotypical why you have trouble organizing ideas, and that process can be frustrating.” Her comment reflects the stigma surrounding self-disclosure for some clients.

Clients also reported that communication was best when their tutors listened to their needs. For clients whose sessions were email-based or virtual, that listening took the form of providing detailed and conversational feedback with a positive and encouraging tone. Susanna, who is a graduate student completing her degree online, shared her successful virtual consultations. She elaborates that her tutor gives her the option to be on or off-camera, which she appreciates because sometimes she needs to interact and see someone, “kind of like with body doubling sessions.” It keeps her on task and helps with writing accountability. Lucas has a similar outlook on virtual tutoring assistance, particularly email-based tutoring. He believes it is an accessible resource that should be kept even after COVID-19: “I am all about virtual [tutoring]. I love it!”. This goes to show that successful experiences in the writing center were grounded in intentional engagement with what student writers need, active listening, and flexible modes of tutoring.

Moments of Disclosure for Tutors and Clients

When I interviewed tutors and clients with ADHD about whether they have disclosed having ADHD in a tutoring session before, their responses were varied. I also asked them to narrate any experiences of disclosure and explain their decision to disclose or refrain from doing so.

For the two tutor-participants, their disclosure depended on what their circumstances were and who they were sharing it with, as there is more at stake when it comes to their professional identity at the writing center. Dan remarked that he would not disclose it right off the bat; he would only disclose it with people who have worked with him and would rather explain how he functions because of his ADHD on a given day, instead of opening up about his diagnosis. Lindsey confessed about having a few bad sessions when she first started tutoring, which made it difficult to disclose. However, after getting used to her role as a tutor, she said she tries to be honest about her limitations and be open about what works to navigate the session. She added that,

“I am not going to force it into the conversation, so if it’s not relevant, then I won’t say it. If I think it will become relevant, then I usually say it. Also, nobody ever has a problem with this. Most people are like, ‘cool,’ or ‘I have ADHD too.’”

As for clients with ADHD, some reported disclosing their ADHD and their need for accommodations. Two clients clarified that they usually disclosed their ADHD and wrote down what they needed in a client questionnaire before their tutoring appointment. One of the clients, Melissa, explained how this kind of information is helpful for tutors to know. She was more comfortable disclosing her ADHD at her university and was able to connect with other neurodivergent students, as opposed to her high school where “it was an ableist environment.” Lucas also thought it was helpful for a writing center to know upfront. This client, who disclosed having ADHD and autism, said he was more likely to share having ADHD than his high-functioning autism in the pre-consultation form; other times, he would disregard mentioning his diagnosis and instead walk the tutor through what writing feedback he needs, especially that he strictly books email-based tutoring that does not include real-time interaction with the tutor. He noted that he benefits more when the tutor’s feedback is more specific and structured in the comment bubbles.

Other clients preferred not to disclose their ADHD because they do not see the need for it. Cynthia said she would only mention “extra cues” in the client questionnaire or point out needing extra support in her sessions. She goes on to say that many individuals with ADHD “do not want that stigma around [them].” Another client, Francesca, expressed how nervous it makes her to disclose having ADHD:

“Usually, in an academic sense, or if I’m trying to get help with something related to my ADHD, I do not end up telling people that I have it because I don’t want them to assume what I need. I’d rather describe to them what I’m having trouble with, based on the exact traits they are, rather than saying, ‘here’s this diagnosis so you can make assumptions about what you think.’”

The next section on writing processes of tutors and clients with ADHD sheds light on the diversity of neurodivergent writers and writing approaches.

Writing with ADHD: Process, Strengths, and Struggles

Writing Processes

In their interviews, all tutors and clients were asked about their writing processes as neurodivergent writers. Specifically, they were asked about what their different writing stages looked like, and what writing struggles and strengths they potentially attribute to having ADHD.

With regards to their processes, most tutors and clients focused on their time management, especially as it pertains to starting with their draft or brainstorming for ideas. For example, Melissa said that she spends much of her time outlining her writing, which prevents her from cranking out a paper at the last minute. On the other hand, participants like Susanna resort to setting timers to stay on task. Three interviewees also mentioned their emotional preparedness and procrastination habits. Lindsey, for example, talks about giving some time to not write. She describes her writing process as such:

“I need to give myself at least one day to not do it. Giving yourself some runaway, depending on what the paper is and how much emotional energy it will take from you is important.”

Some discussed accessible tools they used in their writing process. To track his time and stay accountable, Lucas works with Toggl to plan out his writing and estimate how much time each writing task will take; he also points out that using this application “forces [him] to move on instead of stagnate and keep spinning [his] wheels over and over again.” Other clients resorted to auditory and visual tools in their writing. For instance, Susanna and Cynthia favored using voice-to-text options, which helped them listen to their ideas and revise their writing. Other clients, like Melissa and Francesca, utilized post-it notes and color-coding to help with their reading and writing processes.

Writing Strengths and Struggles

Aside from their writing processes, I asked all participants about their writing strengths and struggles that they might relate to having ADHD. In their interviews, most participants, whether tutors or clients, discussed their ability to take abstract ideas and visualize them in ways a neurotypical writer might not. Curiosity and creativity were some of the main keywords correlated with what the participants perceived to be their writing strengths. For example, one of the clients, Cynthia, talked about how she can easily “paint a picture for those reading [her paper]… so people can understand [her] vision and thoughts.” Similarly, one of the tutors, Dan, elaborated on his ability to map out ideas easily and quickly:

“I hoard or collect all these little pieces of information, and that helps me make connections between things in ways people enjoy when they read my writing, and they’re like, oh, I never thought about that before.”

In terms of participants’ writing struggles, I noticed two main struggles throughout their answers: structure and motivation. The reason why I asked about challenges they faced with their writing is because I was curious about how their neurodivergence might interject with how they went about their writing tasks. A few participants said they struggled with organization. One of the clients, Francesca, explained her trouble with making sense of her ideas, deciding what to prioritize, and making her thoughts flow coherently and clearly. She explained that she will write her ideas but find trouble in connecting them back to the thesis of the paper and narrowing down the focus of her essay. Another client, Cynthia, discusses a similar issue, remarking that transitioning to write the next idea or paragraph becomes frustrating sometimes. Lucas describes himself as “scatterbrained” because he realized he writes backwards. He goes on to say: “I tend to be a bit of a system thinker. My mind goes in every direction at the same time at a hundred miles per hour… It’s like an octopus.”

Motivation to write is another common problem that some participants mentioned. One of the clients, Susanna, shared how she puts pressure on herself to do things the “right” way and to write in ways she is expected to; this is why she spends most of her writing time in the revision phase. Similarly, Dan reported how he would wait until the last minute to write his papers, when there is a sense of urgency to do it. He mentioned how this might have to do with wanting to perfect every sentence, which makes his writing process painstakingly slow.

Overall, the participants’ diverse modes of writing and the writing challenges they face provides context and understanding on how diverse learning styles work.

Writing Center Support for Tutors and Clients

In the survey and subsequent interviews, I asked tutors and clients with ADHD about the kind(s) of support they want in their writing center, and more generally on campus, as well as their thoughts on successful strategies to approach a session with clients who have ADHD. Three major recommendations about support from the survey and interviews with tutors and clients emerged: considering accessible modes of tutoring in sessions, incorporating more conversations about disability in tutor education and training, and working on more collaboration with on-campus resources to combat the cultural stigma surrounding disability.

Accessible Modes of Tutoring in the Writing Center

Clients and tutors with ADHD provided their insights about the kinds of support they need. I noticed an overlap in survey and interview results regarding the suggestions of participants, which all focused on multimodal accessibility in tutoring and in the writing center space, namely temporal, spatial, and visual accessibility.

Most clients from the survey said they want more support when it comes to allocating additional time in a tutoring session or offering more appointments per week. Similarly, in the interviews, Francesca thought it would help to “[offer] longer time slots to break things down.” Another client, Cynthia, noted that she “always block[s] off an hour instead of half an hour because [she] needs the extra support” in tutoring sessions.

In terms of spatial accessibility, one of the tutors from the survey encouraged investing in more accessible rooms in the writing center: “I think investigating in sound-absorbing rooms would be good not only for tutors and clients with audio processing issues, but also those who are hearing impaired. I had one such client last semester whose session had to be moved to a different room.” Several of the interview responses mirror the tutor’s suggestion. For example, Francesca finds that “providing access to quiet rooms” is important. Another client, Susanna, who regularly books online synchronous sessions with her tutor, shared how virtual tutoring is beneficial to her: “My tutor gave me the option to be on camera or off-camera, which I appreciate because sometimes I feel like actually seeing someone, kind of like with body doubling sessions. It’s actually helpful to keep me on task.”

For some clients in the survey and interviews, the need for utilizing a multimodal multisensory (i.e. visual) approach in tutoring was encouraged. In both the interview and survey responses, clients stated that they appreciated detailed and visual feedback. One client from the survey explained that when tutors use comment bubbles in electronic tutoring to point out what they’re saying, it models to clients how they could revise; it also helps them learn better. Likewise, in his interview, Lucas stated that giving “precise feedback in the comment bubbles help[s] [him] out.” Another client in the survey mentioned that allowing digital collaboration between tutor and client should always be an option because “[t]hat way, students can be in a space where they feel comfortable and so can the tutor.” Participants’ recommendations to employ a multimodal approach in tutoring interactions reflects the need for writing centers to offer an outlet for clients and tutors to self-advocate for their diverse needs and to discuss how accessibility can work in their favor.

Conversations About Neurodivergence in Tutor Education and Training

Support for neurodivergent tutors and clients in the writing center also involves a conversation about staff education and training. One of the tutors in the survey results expressed that having more conversations as part of tutor education and training about neurodivergence overall would be productive. The interview portion affirms the need for more of these conversations. Susanna said she would appreciate it if there was more “awareness on how neurodivergent people operate… keeping [her] accountable to actually work and [be] reassuring [she is] on the right track.” Her response suggests the importance of incorporating conversations surrounding neurodivergence in tutor education and professional development.

The two tutors from my interviews address a similar approach to supporting tutors and clients with ADHD. Both tutors believe tutors and admins need to look into further research on neurodivergence, including ADHD, to help in crafting better staff education and resources. Dan shared that he knew so little about neurodivergence before he got diagnosed. The other tutor, Lindsey, adds that there is no prescribed way of tutoring and handling different sessions; however, “encouraging people to talk about their experiences in a sort of loose way [in tutor education]” instead of individually reflecting on tutoring is useful, especially because it will prompt dialogue among tutors.

Collective awareness of neurodivergence in writing center conversations can therefore empower tutors who are neurodivergent and involve their perspectives in tutor programming. Dan forwards his idea in the interview, encouraging tutors with ADHD and writing center tutor and professionals to think about how neurodivergence might intersect with the ways we interact and tutor in the writing center. He invites fellow tutors who are neurodivergent to “develop an individualized tutoring stance… and think about how [ADHD] isn’t a limitation when they are tutoring… and to think about how [it’s] something that they can embrace.” This tutoring stance can be implemented in pedagogical approaches to training tutors. Perhaps we can integrate this stance as a pedagogical practice in tutor training, in order to encourage students/trainees to speak openly and advocate for themselves without fear of judgment or shaming.

Institutional and Cultural Barriers to Tutor and Client Support

Lastly, when it comes to support, participants, whether tutors or clients with ADHD, shed light on their frustration about the process of asking for and receiving accommodations, much of which did not work for their individual needs. Many participants noted their unsuccessful experiences in academic spaces they are and were part of.

Some of the survey respondents, mainly clients, indicated their desire for stronger collaboration with the disability resource center on campus. One client shared their experience with the disability resource center, which related to accommodations they were being denied: “I have not filed with the disability resource center. When I tried to get into undergrad, they told me my grades were good enough without the need to receive support.” Their unsuccessful accommodation is common among other clients who tried to receive support from their disability resource center but were declined the support they needed.

Correspondingly, Cynthia recounted her failed experiences with the disability resources office in her interview:

“When I went to the disability office as an undergrad and told them about my disability. They told me my GPA and grades were fine. It frustrated me. That’s actually why I became a teacher because we’re not dumb, we can learn… When [my institution] shot me down on that one, I re-enrolled for my second masters and got a scholarship. Things were more against me then.”

Note that four out of the five clients I interviewed mentioned their struggle receiving writing support in high school or academic support from resource centers on campus, which tap into the institutional barriers that limited their student access to the support they need.

In her interview, Lindsey highlighted how we need to break down the cultural problem, and more so the stigma, that frames neurodivergence as a challenge and consequently limits the institutional support that neurodivergent tutors and writers can receive. She strongly states,

“I think we have a cultural problem that frames neurodivergence as a challenge that we must overcome. It’s like we’ve gotten to a point where it’s okay to be neurodivergent for the most part, but accommodations are considered roadblocks that a person has. I think, especially for ADHD, we need to not frame it that way, in this sort of environment, because there are things that ADHD advantages you in, with being a tutor.”

This speaks to what one of the tutors in the survey wrote. The tutor expressed that we need to think of the writing center as a rebel space. They believed it was important to:

“[A]cknowledge that the systems/structures in place with the university/in academia writ large are what make ADHD disabling. Acknowledge and explore the possibilities of the [writing center] as a third or rebel space which can help our students find ways to think using the ways their brains actually formed, rather than upholding the structures of academia to try and fit them into a neurotypical mold. That’s a losing game.”

Discussion

Framing writing centers as rebel spaces, according to this tutor’s suggestion, is a powerful sentiment. It indicates the need for writing centers to advocate for its neurodivergent tutors and clients who might not find support elsewhere and to act as a liaison that communicates their needs with academic resources concerned with student well-being.

In studying how tutors and clients with ADHD describe and perceive their past, I have noticed that they did not think of their neurodivergence in a vacuum. Tutors, particularly, emphasized how different facets of their identities, like their neurodivergence, gender, and profession, become visible, interfere, and interject at different moments in the writing center. In their introduction to Out in the Center, Harry Denny and fellow scholars (2018) argue that writing centers are not shut out from the socio-cultural and political forces in the public; in fact, writing centers reflect the communities surrounding them. This applies to the tutors and clients entering the writing center, who are continuously constructing themselves, intentionally and unintentionally, and marking parts of their identity while simultaneously keeping other parts, sometimes their neurodivergence, invisible. The participants are actively negotiating their identity, perhaps in ways that both protect and empower them. This “dance of identity,” as Denny (2005) terms it, implies that neurodivergent tutors and clients are highly aware of their positionality and the power dynamics involved in their interactions, and their writing centers should also be aware. A writing center rebels when it outright rejects to participate in the stereotyping of neurodivergent individuals on its campus as deficient and treating them as an afterthought. A writing center rebels when it decides to learn from its neurodivergent community.

Simultaneously, participants approached their disability disclosures differently; some thought it was not necessary while others believed it helped them negotiate their access needs. In their work, Bartels (2020) recognizes that disclosure is a vulnerable practice. Additionally, in their teaching, Bartels (2020) finds it imperative to refrain from forcing students to disclose in/visible facets of their identity, like their gender and disability, as a means of alleviating the burden of disclosing or outing their students. Writing center practitioners can adopt this line of thinking: they need to be cognizant of the complex identities of their tutors and clients in order to cast away ableist assumptions about who they are and how they learn, and to invite them to speak up about their disabled experiences at their own terms. This means that writing centers need to also resist the urge to diagnose, as Hitt (2021) recommends, because it puts undue labor on tutors and clients to prove that they need support. In doing so, writing centers can figure out how to collaboratively tend to their disabled community’s needs and counter the dominant misconceptions about disability.

Looking outward, participants found their current writing center space to be an environment that does not belittle or ridicule neurodivergent student writers who are seeking support with their writing. In this sense, the writing center needs to continuously assess whether it is excluding certain students and to work on developing ways to be a space of openness and adaptability for diverse identities, including neurodivergent identities. In the survey, one of the participants noted that the writing center could be a “third place,” a place where we can rebel and correct the problematic cultural model of disability as something that makes individuals less than. As Babcock and Daniels (2017) emphasize, we need to follow through and work on actualizing our space, with a more equitable model that centers neurodivergent experiences. This actualization starts with more collaborative conversation about what access looks like in local contexts and situations. As writing center professionals, we need to assess the culture that is being invoked by writing center workers and clients within the academic institution to which we belong. Dolmage (2017) remarks that if we are to create a culture of accessibility for all (and, more pressingly, disabled individuals), we must acknowledge that accommodations are not enough to uphold this culture: “[they are] not where accessibility should stop” (Dolmage, 2017, p. 10). To imagine how an accessible-driven culture can be created for its neurodivergent community, including writers and tutors with ADHD, administrators need to engage with their tutors and clients about issues of access and conversations around disability.

As writing center tutors, we might think about the nuances of disability as it intersects with gender, race, ethnicity, language, and other identity facets. These questions will take care, time, and continuous reassessment of how our writing centers can resist ableist pedagogies and mentalities that go unnoticed or are slipped under the rug. It is also important to not operate on the false pretense that writing centers are safe for all, as McNamee & Miley note (2017), and to instead actualize the writing center as a political arena that resists discrimination and oppressive power systems.

Aside from the cultural mindset to adopt in our writing center work, it is important to understand that writing processes are diverse and atypical. Listening to participants’ struggles and strengths with writing as it relates to their neurodivergence, I wanted to center their embodied and nuanced experiences because writers with ADHD should not be “flattened by binary understanding of [their] disability” (Elston et al., 2022, para. 1). As writing center professionals and tutors, we need to avoid biased assumptions about disability and employ a framework of empathic listening that is kairotic, requiring openness and vulnerability (Anglesey & McBride, 2019; Oweidat & McDermott, 2017).

Results have also shown that empowering tutors and writers can take many supportive routes: within the tutoring session itself, in tutor education, and in partnerships across campus. In the findings, participants shared what they considered accessible modes of tutoring that exist or that need to be changed, like body doubling for accountability, the multiple modes of connecting in a tutoring session (whether online, asynchronously, or in-person), using sensory material or visual references, and figuring out resources for individual needs. These kinds of support extend lines of communication between tutor and client and foster the kind of culture where collaboration and transparency are welcome. For example, in terms of spatial accessibility of our writing centers, the tutor’s suggestion directs writing centers to consider how their physical space can be reconfigured to better support tutors and clients when they are doing their sessions. It starts with asking the tutors and clients who are using the space regularly and sometimes over a long period of time. The larger goal is not to succumb to quick fixes in tutoring when disability comes up, but to question the culture of access we permeate in tutoring sessions and work on “transformative access” (Brewer et al., 2014) that continuously questions and reconsiders the very idea of how we allow access in our writing centers and sessions.

We need to consider how to incorporate this transformative ideology to support tutors and clients with ADHD in tutor programs. First, we could develop comprehensive modules in tutor training and curricula and in ongoing tutor education on neurodivergence and disabilities; this is still a rigorous conversation that has not been emphasized enough. If we were to develop a tutor education curriculum with neurodivergence in mind, as writing center administrators and practitioners, where would it fit within tutor programming? When we talk about tutor education, we need to think larger than incorporating a single unit or reading material on the topic; rather, in developing future modules to train new and returning tutors, a disability studies perspective, in intersection with other critical topics, such as racial justice and linguistic diversity, must be taken into account. Such modules will benefit writing center directors and tutors because their engagement with the material will help position themselves as allies and activists in their own writing and tutoring spaces, even when they are not neurodivergent. Additionally, Wilson and Fitzgerald (2012) emphasize the notion of “a metacognitive, flexible third space—a part of the university but also apart from it” (p. 12), which echoes what one of the participants stated about the potential of writing centers. The scholars encourage tutor training that guides tutors to adopt a more empathic understanding, which starts with acknowledging their biases and recognizing that a top-down hierarchical communication does little to achieve mutual understanding and open conversation. This pedagogical approach can be part of tutor education on disability studies.

Overall, I have come to terms with the significance of assessing the kind of culture we are fostering for all those who walk into the writing center. As Rinaldi (2015) notes, viewing disability as a deficit that individuals need to account for, fix, and attune is problematic. In the study, tutors and clients continuously alluded to wanting spaces where they are heard. For many participants, accommodations can only go so far. In fact, most of the respondents faced backlash and shaming when they asked for and sought accommodations within their institution—it was a dead end that was frustrating, belittling, and burdensome. In that manner, accommodations are not sustainable, and disclosure sometimes leads nowhere. A more helpful long-term strategy is to work towards changing the rhetoric of disability as a deficit, or a subversion from normalcy to be fraught (Dolmage, 2017; Price, 2011). The writing center, part of the academic institution, can be a place where we can work on changing this line of discriminatory thinking.

Conclusion

This project was born out of the need to imagine, assess, and reconstruct the writing center space using neurodivergence as a lens to open up difficult or conflicting conversations about the ideologies, guidelines, and practices that continue to be upheld by the dis/abling systems in our institutions and writing centers. To foster and actualize an inclusive, accessible, and able-ing (rather than ableist) communities on campus, within our classrooms, and writing centers, it is time we actively listen, reflect on structures of service to our diverse student body, evaluate the underlying discriminatory thinkings and acts that students who are neurodivergent face in learning and writing spaces, and collaborate with students with disabilities.

Perhaps a purpose and outcome of accessibility is to rebel against programmatic and institutional tendencies to fit students, staff, and faculty into a “neurotypical mold,” as one of the participants expressed. In rebelling, or “snapping” (Ahmed, 2017), against these tendencies, there is an opportunity to frame neurodivergence as an abundant negotiation of identities and cultures coexisting and collaborating in the writing center. Dembsey (2020) urges us “to at least try” (para. 55). Writing centers should try harder and be on the constant look out for opportune moments to learn from and alleviate disabled voices in its community. The work is not nearly done nor will it ever be, as we seek to continuously consider how our writing centers can rumble and rebel against disability injustices.

References

Anglesey, L. & McBride, M. (2019). Caring for students with disabilities: (Re)defining welcome as a culture of listening. The Peer Review, 3(1). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/redefining-welcome/caring-for-students-with-disabilities-redefining-welcome-as-a-culture-of-listening/

Babcock, R. D. (2015). Disabilities in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/babcock-131

Babcock, R. D., & Daniels, D. (2017). Writing Centers and disability (A. D. Smith & T. G. Smith, Eds.). Fountainhead Press.

Bartels, R. (2020). Navigating disclosure in a critical trans pedagogy. Peitho, 22(4). https://cfshrc.org/article/navigating-disclosure-in-a-critical-trans-pedagogy/

Batt, A. (2018). Welcoming and managing neurodivergence in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 15(2). http://www.praxisuwc.com/325-batt

Brewer, E., Selfe, C. L., & Yergeau, M. (2014). Creating a culture of access in composition studies. Composition Studies, 42(2), 151-154, 186, 189.

Cecil-Lemkin, E., & Johnson, L. M. (2021). Developing a multimodal toolkit for greater writing center accessibility. Another Word. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/multimodaltoolkit/

Daniels, S., Babcock, R. D., & Daniels, D. (2015). Writing centers and disability: Enabling writers through an inclusive philosophy. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/daniels-et-al-131/

Degner, H., Wojciehowski, K., & Giroux, C. (2015). Opening closed doors: A rationale for creating a safe space for tutors struggling with mental health concerns or illnesses. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/degner-et-al-131

Denny, H. (2005). Queering the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 25(2).

Dembsey, J. M. (2020). Naming Ableism in the Writing Center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 18(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/181-dembsey

Denny, H., Mundy, R., Naydan, L. M., Sévère, R., & Anna, S. (Eds.). (2018). Out in the center: Public controversies and private struggles. Utah State University Press.

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

Elston, M. M., Green, N., & Hubrig, A. (2022). Beyond binaries of disability in writing center studies. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 19(1). https://www.praxisuwc.com/191-elston-green-and-hubrig

Garbus, J. (2017). Mental disabilities in the writing center. Writing centers and disability (R. D. Babcock & S. Daniels, Eds.). Southlake, Texas: Fountainhead Press.

Hitt, A. H. (2012). Access for all: The role of disability in multiliteracy centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 9(2). http://www.praxisuwc.com/hitt-92

Hitt, A. H. (2021). Rhetorics of overcoming: Rewriting narratives of disability and accessibility in writing studies. Champaign, Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English.

Kerschbaum, S., Eisenman, L., & Jones, J. (2021). Negotiating disability: Disclosure and higher education. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9426902

Kleinfeld, E. (2018). Taking an expansive view of accessibility: The writing center at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Composition Forum, 39, https://compositionforum.com/issue/39/msu-denver.php

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2016). Strategies for writing center research. Anderson, South Carolina: Parlor Press.

McNamee, K., & Miley, M. (2017). Writing center as homeplace (A site for radical resistance). The Peer Review, 1(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/braver-spaces/writing-center-as-homeplace-a-site-for-radical-resistance/

Price, M. (2011). Mad at School: Rhetorics of Mental Disability and Academic Life. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.1612837

Rinaldi, K. (2015). Disability in the writing center: A new approach (that’s not so new). Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1), 9-14.

Stark, S., & Wilson, J. (2016). Disclosure concerns: The Stigma of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Writing Centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(2), https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/45599

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th edition). SAGE.

Walker, N. (2014). Neurodiversity: Some basic terms and definitions. Neuroqueer: The Writings of Dr. Nick Walker. https://neuroqueer.com/neurodiversity-terms-and-definitions/

Wilson, N. E., & Fitzgerald, K. (2012). Empathic tutoring in the third space. Writing Lab Newsletter, 37(304), 11-13.

Zmudka, T. (2018). Embracing learning differences: Spreading the word to writing centers and beyond. In H. C. Denny, R. Mundy, L. M. Naydan, & R. Sévère (Eds.), Out in the center: Public controversies and private struggles (221-238). Colorado: University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.7330/9781607327837

Appendix A

Table 1

Participants and Relevant Demographics and Positionality.

Note. This table demonstrates the participants, using pseudonyms, their participant type (as tutor or client), and their relevant demographics/positionalities.

Appendix B

Survey: Writing and Tutoring with ADHD in the Writing Center

Are you a current tutor or client at the writing center?

-

- Tutor

- Client

Survey Questions: Writing Center Peer Tutor

- Are you an undergraduate tutor (UTA) or graduate tutor (GTA)?

- Undergraduate tutor (UTA)

- Graduate tutor (GTA)

- Approximately how many semesters have you been working as a writing center tutor?

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five or more

- Mark the answer that best describes you.

- I am diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- I think I have ADHD but have not been diagnosed

- I do not have ADHD

- What type of ADHD were you diagnosed with, or do you think you have? [following 3a and 3b]

- The inattentive type

- The impulsive/hyperactive type

- The combined type

- I’m not sure

- Have you ever disclosed your symptoms or diagnosis to any of the following? Check all that apply. [following 4]

- Yes, to my writing center administration

- Yes, to my writing center coworkers

- Yes, to students I have tutored

- No

- Read the following statements and indicate the effect your ADHD symptoms have had on your writing abilities: My ADHD symptoms have affected my writing abilities.

- Significantly

- Moderately

- Slightly

- Never

- Read the following statements and indicate the effect your ADHD symptoms have had on your tutoring abilities: My ADHD symptoms have affected my tutoring abilities.

- Significantly

- Moderately

- Slightly

- Never

- Which of the following did your tutor training cover? Check all that apply.

- N/A (I received no tutor training)

- How to tutor students with learning disabilities

- How to tutor students with ADHD specifically

- How tutors with learning disabilities can cope with these issues in the writing center

- How tutors with ADHD can cope with these issues in the writing center

- My training did not discuss these topics

- What could your writing center do to provide support to tutors with ADHD? Mark all that apply.

- Conduct training sessions about learning disabilities generally

- Conduct training sessions about ADHD specifically

- Provide tutors with strategies that encourage the use of multiple modes of communication in their tutoring sessions

- Guide tutors with ADHD to use campus resources

- Hold conversation groups to reflect on tutoring experiences with ADHD

- Designate more sound-absorbing rooms for tutoring in the writing center

- Provide assistive technology that supports tutors with ADHD

- Other

- What could your writing center do to provide support to clients with ADHD? Mark all that apply.

- Offer more tutoring appointments per week

- Allow extra time during a tutoring session

- Match clients with ADHD with more experienced tutors

- Encourage a multisensory approach in tutoring sessions (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic techniques, for example)

- Designate more sound-absorbing rooms for tutoring sessions in the writing center

- Provide assistive technology that supports clients with ADHD

- Collaborate with the disability resource center to develop training materials for tutors

- Other

- I am interested in interviewing existing tutors and writers with ADHD who completed the survey. If you answer yes, you will be redirected to a second survey to provide your contact information. All your answers in the current survey will still remain anonymous. Whether you answer yes or no, once you click next, your answers to the current survey will be submitted.

- Yes

- No

Survey Questions: Writing Center Client

- Are you an undergraduate student or graduate student?

- Undergraduate student

- Graduate student

- What year are you in? [for undergraduate students]

- Sophomore

- Junior

- Senior

- How many years have you been in graduate school (including the current year) [for graduate students]

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five

- Six or more

- Mark the answer that best describes you.

- I am diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- I think I have ADHD but have not been diagnosed

- I do not have ADHD

- What type of ADHD were you diagnosed with, or do you think you have?

- The inattentive type

- The impulsive/hyperactive type

- The combined type

- I’m not sure

- Have you ever disclosed your symptoms or diagnosis to any of the following? Check all that apply. [following 5]

- Yes, to the disability resource center

- Yes, to my writing center staff

- Yes, to my writing center tutor

- Yes, to my classmates and/or friends

- No

- Read the following statements and indicate the effect your ADHD symptoms have had on your writing abilities: My ADHD symptoms have affected my writing abilities.

- Significantly

- Moderately

- Slightly

- Never

- What specific strategies do you think have worked for you in tutoring sessions? Mark all that apply.

- Brainstorming ideas out loud

- Setting deadlines for accountability

- Using specific instructions to tackle writing concerns

- Seeing the bigger picture (metacognition)

- Outlining content

- Organizing ideas with transition for logical order

- Using multiple modes of communication

- Other

- Have you found the support you need in the writing center?

- What could your writing center do to provide support to clients with ADHD?

- Offer more tutoring appointments per week

- Allow extra time during a tutoring session

- Match clients with ADHD with more experienced tutors

- Encourage a multisensory approach in tutoring sessions (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic techniques, for example)

- Designate more sound-absorbing rooms for tutoring sessions in the writing center

- Provide assistive technology that supports clients with ADHD

- Collaborate with the disability resource center to develop training materials for tutors

- Other

- I am interested in interviewing existing tutors and writers with ADHD who completed the survey. If you answer yes, you will be redirected to a second survey to provide your contact information. All your answers in the current survey will still remain anonymous. Whether you answer yes or no, once you click next, your answers to the current survey will be submitted.

- Yes

- No

Appendix C

Interview Questions with the Writing Center Peer Tutor

In this interview, I would like you to answer the following questions to better understand what happens in your tutoring sessions, particularly as it relates to your ADHD, and to explore how you conduct tutoring with different clients. The duration of this individual interview will be around 35-40 minutes.

ADHD Diagnosis

- You have shared with me that you have ADHD, have you been diagnosed with ADHD or identify as having ADHD?

- Yes

- No

- What type of ADHD were you diagnosed with, the inattentive type, the hyperactivity type, or the combined type?

- Inattentive type

- Hyperactive type

- Combined type

Writing Center Tutoring Experiences with ADHD Diagnosis

- Could you tell me about past tutoring sessions you consider to be successful?

- Knowing you have ADHD, what tutoring strategies have proven helpful?

- Could you tell me about past tutoring sessions you consider to be bad, overwhelming, or frustrating?

- Knowing you have ADHD, what tutoring strategies did not work?

- Have you ever disclosed having ADHD in a tutoring session?

- If you have, could you narrate your experience(s)?

- If you have not, could you explain why you chose not to do so?

Writing Center Experiences with ADHD Clients

- Research on tutoring clients with ADHD suggests some of the following tutoring methods:

- Brainstorming ideas out loud

- Setting deadlines for accountability

- Using specific instructions to tackle writing concerns

- Helping clients see the bigger picture (metacognition)

- Outlining content

- Organizing ideas with transition for logical order

- Using multiple modes of communication

- Have you knowingly tutored a client with ADHD?

- Have you used any of these methods in a session? If you have, were they helpful or not? Please explain.

- Are there any other tutoring methods that you think might be helpful when tutoring a client with ADHD?

- What suggestions do you have for training tutors with ADHD, to work with

- Clients with ADHD?

- Clients without ADHD?

Writing Strengths and Struggles

- Turning to your own writing, what struggles and strengths do you connect to having ADHD?

- Could you talk about writing strategies that have helped with your ADHD?

- How conscious are you of the writing processes that worked or did not work last time you had a paper or project due? Could you give an example?

- Do any of your personal struggles with writing interfere with your tutoring? Please explain.

Final Remarks

- Would you like to add anything else about your tutoring and/or writing experiences in relation to having ADHD?

Interview Questions with the Writing Center Client

In this interview, I would like you to answer the following questions to better understand your experience in writing and tutoring sessions, particularly as it relates to your ADHD. The duration of this individual interview will be around 35-40 minutes.

ADHD Diagnosis

- You have shared with me that you have ADHD, have you been diagnosed with ADHD or identify as having ADHD?

- Yes

- No

- What type of ADHD were you diagnosed with, the inattentive type, the hyperactivity type, or the combined type?

- Inattentive type

- Hyperactive type

- Combined type

Writing Center Experiences with ADHD Diagnosis

- Could you describe your experience coming to the Writing Center?

- Could you tell me about past tutoring sessions you consider to be successful?

- Could you tell me about past tutoring sessions you consider to be bad, overwhelming, or frustrating?

- Knowing you have ADHD, are there specific approaches or methods a tutor has employed in the session that helped your writing? What about methods that did not work for your writing?

- Have you ever disclosed having ADHD in a tutoring session?

- If you have, could you narrate your experience(s)?

- If you have not, could you explain why you chose not to do so?

- What recommendations do you have for tutors who might encounter clients with ADHD?

Writing Strengths and Struggles

- What are writing struggles and writing strengths you connect to having ADHD?

- Do you use any writing strategies that have helped with your ADHD? Please specify and give examples.

- How conscious are you of the writing processes that worked or did not work last time you had a paper or project due? Could you give an example?

Final Remarks

- Would you like to add anything else about your tutoring and/or writing experiences in relation to having ADHD?

Footnotes

- Neurodivergence is a term coined by Kassiane Asasumasu in 2000. Neurodivergence is a concept used when an individual’s mental or neurological development diverges from what is considered medically and culturally typical (as cited in Walker, 2014). I use the term to describe neurodivergent tutors and clients in my study who shared that they were medically diagnosed with ADHD or self-identify as having ADHD.↩

- IRB #: IRB-2021-1791, approved on January 12, 2022.↩

- Initially, I contacted 11 participants, eight clients and three tutors in total, who filled out the survey and signed up for an interview. After reaching out to them, only two tutors and five clients decided to go forward with an interview.↩

- In reporting the findings, I chose to exclude participant recounts of their diagnosis after careful consideration. My initial intent behind asking about their backstories was to establish rapport, connect with them as a tutor and writer with ADHD myself, and learn about their histories with ADHD. In working on this paper, I realized that asking participants about what type of diagnosis they had was a problematic question. Asking about an individual’s diagnosis also assumes that one has access to healthcare and/or on-campus resources. I ultimately decided to exclude their backstories, as it was beyond the goals and scope of this research.↩