Summer Carlson, University of Iowa

Kyler Johnson, University of Iowa

Introduction

At institutions of higher education, writing centers often act as their names foretell: they can be hubs for appointments where trained tutors interact with students who need writing assistance. The anxieties, the struggles, and the successes involved in this specific interaction are well-documented, offering a breadth of writing center literature to help acquaint new tutors with student writers’ challenges and to enlighten experienced tutors with new perspectives. Alongside this traditional format, some universities, such as the University of Iowa where we worked and studied, another type of program has sprouted from this hub. Reaching into specific classrooms each semester, the Honors Writing Fellows program has spread the impact of writing tutoring beyond the traditional center space.

A large, public institution hosting over 30,000 students across undergraduate and graduate programs and over 200 course programs between majors, minors, certificates, and concentrations, the University of Iowa provides an academic home to students of various interests and writing-experience levels. Despite its size, the University of Iowa consistently is ranked as a top university in incorporating writing across the curriculum (US News, 2023), showcasing that writing remains a priority across academic disciplines regardless of students’ interests. As a result, access to writing resources is an essential part of the wider university environment. The University of Iowa Writing Center responds to this need, providing services to about 2000 separate students per year through a staff composed of 30 writing fellows, 15 graduate tutors, and a director and assistant director who also tutor. Inducting a new cohort each year, the University of Iowa Writing Fellows Program employs a mixture of second- third-, and fourth-year students who operate in teams of two to four students who are assigned to a specific, semester-long course. While called the Writing Fellows program at the University of Iowa, at other institutions this role may also be called embedded writing specialists, writing ambassadors, or course-embedded writing tutors/consultants, among others.

Fellows work individually with 8-12 students from a specific course on two major writing assignments each semester. Student participation is mandatory and is often factored into the assignment grade. As opposed to the traditional writing center appointment system, the Writing Fellows program schedule is more prescribed, with fellows and the course instructors to whom they are assigned working together at the beginning of the semester to determine which weeks the fellows will receive and comment on student drafts and schedule one-on-one student conferences. As a result, the rhythm of a writing fellow’s schedule—they comment and conference on the first major assignment before midterm and the second after midterm—differs greatly from that of a more traditional writing center appointment tutor. Rather than assessing a draft’s issues, offering feedback, and conferencing with an individual student within the span of 30 minutes to an hour, writing fellows break down the process, juggling a larger caseload of students.

Comparing fellowing with tutoring is of particular interest to us, as we both have operated in the roles of writing fellow and writing center tutor as undergraduates. Carlson served as a writing center tutor for one year and a fellow for two years, including one semester abroad in Ireland during which she fellowed virtually, sometimes late in the evening. Courses she fellowed included Interpretation of Literature, Rhetoric, and Sociology. Johnson, on the other hand, served for three years as a fellow—supporting classes in Rhetoric, Interpretation of Literature, and Diversity in Health—and two years as a writing center tutor, where he worked with clients ranging from international professors wanting to review technical articles for clarity to first-year students wanting to polish papers for their Rhetoric and Literature general education requirements. Both of us now work as professional tutors, carrying our college skill set beyond graduation.

In this article, we examine how the skills and perspectives gained from each program can complement one another. We have seen not only how these programs can differ from each other, demanding the development of overlapping but different skill sets, but also how they can inform one another on a practical level. In the sections that follow, we recount some of our experiences with each program, highlight key observations that distinguish and connect these two different tutoring programs, and offer narratives that encourage writing centers to consider the benefits of offering both traditional tutoring and writing fellows.

Carlson’s Experiences

Distinguishing the Objective of Both Programs

Going into my first shift in the writing center, the respective roles of the tutor and writing fellow seemed relatively straightforward. As the introduction describes, the two are defined by their own environments, student bodies, and expectations. Hence, the lines between the two seemed unlikely to blur. Each is distinct in its practical considerations, such as the length of time spent with each student, whether there is communication with the instructor, the tutor’s knowledge of the writing being reviewed, and the structural goals of each program. Yet, the longer I worked in each role and deepened my understanding of the work before me, the less I felt I was able to distinguish between the programs’ objectives.

On paper, the tutor seems to be more of a generalist, whereas the fellow takes a step closer to being a specialist, with that greater expertise derived from direct communication with the instructor. As defined by Sue Dinitz and Susanmarie Harrington, “expertise can refer to content knowledge, genre knowledge, disciplinary knowledge, or any combination” (2014, p. 74). The first definition is often adopted in generalist-specialist debates in Writing Fellows Programs about which type of fellow is more effective—one who is majoring in the area in which they are fellowing or one who is outside the area (Kiedaisch & Dinitz, 1993; Severino & Trachsel, 2008) or in Smithgall et al.’s article “Becoming Writing Fellows,” in Geiger-Lee’s section, in this issue of TPR.

However, in differentiating the role of the fellow from that of the tutor, expertise in genre or discipline plays a larger role. When a writing center tutor holds open appointments for students of almost every major, year, and level of writing experience, the probability that an assignment falls somewhere within their general realm of content knowledge is reduced. In my year of tutoring in the writing center, I was tasked with reviewing everything from graduate students’ theses abstracts to medical school applications, neither of which I can exactly consider myself an expert in. I even met with some professors looking for an extra set of eyes on papers and proposals. The only information Iowa tutors receive before each meeting comes from a student-submitted WC Online form, most of which are sparsely filled out, making it difficult for tutors to prepare or research students’ topics in advance of the appointment, especially when working in areas of non-expertise. Because of this challenge, undergraduate tutors often find themselves pointing students towards those with more content knowledge in the field–academic advisors, subject tutors, course instructors, teaching assistants, etc. The best a tutor may be able to do is embrace their generalist role and focus on assignment fulfillment, overall argument, and structural elements, rather than concern themselves with fully understanding the material.

Contrast the tutor’s position with the role of the fellow. Before the semester starts, Iowa writing fellows meet with their assigned instructors to review the two assignments they will be tasked with commenting and conferencing on. Not only does this give us the opportunity to receive clarification on questions about the grading expectations, but it also gives the fellows weeks before receiving drafts to better study the assignment and gain a comfort level with the rubric. Some ask for our input on prompts, meaning fellows can play a role in shaping the assignment themselves. In fact, many of the first papers assigned in a course, especially those based in research, serve as steps into the second. For example, the professor of the social psychology class I fellowed used the first paper on theory as the basis for a report on the student’s own experiment explained in the second paper. Hence, when receiving drafts of the second paper, I can easily remember each student’s interests and goals. Most importantly, by the end of each conferencing week, the fellow has carefully read, commented on, and discussed 10 or more papers; after that much review, we understand the ins and outs of the assignment almost as well as the instructor does. Though different degrees of specialization exist within the fellowing experience—an English major working for a literature course as opposed to a psychology course, for example (see Becoming Writing Fellows, this issue), it seems safe to call the fellow a specialist, if only in the assignment’s written expectations.

Another way to frame the difference between the tutoring and fellowing experiences is through the lens of an equal versus an equitable approach to a writing mentorship. Tutoring seems to be an equal approach because it provides resources and opportunities evenly to a population. It appears that these two programs each fall under a different approach. The goal of the Writing Center tutor seems to be providing an equal opportunity for all students. Almost every student within the University of Iowa has access to these services—whether through the Writing Center or a similar program within their chosen college—and can expect a similar experience no matter the tutor they choose or subject they desire extra help with. Their projects appear to always receive the same thirty or sixty minutes of review from a tutor with an expected generalist approach. In this way, Writing Center appointments are representative of equality in academia.

Writing fellows, on the other hand, seem less structured in limits such as time, and therefore can mold their sessions around the student themselves. The mandated commitment from each student hypothetically ensures that the fellow-student relationship is a consistent one that will bring about a deeper understanding of each individual’s strengths and needs. The goal of the fellow is to bring each student up to the same level of understanding of the rubric, to even out the playing field if you will. A study conducted by Candis Bond at Augustana University found a positive correlation between participation in the fellows program and student confidence in writing ability, despite a few discrepancies. The findings “suggest [Writing Fellows] programs can support all students by normalizing writing support and making it accessible” (Bond, 2020, p. 54). In other words, the Writing Fellows program has the opportunity to increase rhetorical awareness as much as needed for each individual student. Severino and Knight even refer to the fellow as an ambassador in a way the tutor can never be, giving “reluctant students who are ‘Fellowed’ a taste of what the Writing Center offers, which may encourage them to make use of the Center” (2007, p. 27). Hence, the writing fellow appears to serve as the model for equitable writing assistance, at least in concept.

The Writing Center: Expectations vs. Reality

And yet, the most striking thing I learned in the Writing Center is as follows: there is at least one exception to every pattern. The tendencies laid out thus far can only apply to the most by-the-book scenarios, of which there are few. The association of equality with writing centers and equity with writing fellows is weakened when we consider demographics. Though tutors and fellows both meet diverse groups of students, the scope of said diversity is much wider for a Writing Center tutor. As stated earlier, factors like year in school and experience in writing play a large role in shaping the experience of a student looking for writing help. Yet, where these are daily considerations for the tutor, the demographics of a fellow’s students are relatively uniform at the University of Iowa. Most courses we fellow are in the Humanities and Social Sciences, many of them lower level general education requirements. Students in these courses are more likely to be freshmen and sophomores. The courses chosen for fellowing are also less likely to include ESL or UIowa REACH students (a program for those with cognitive or learning disabilities). While these students may receive additional mentorship through other university programs, I have worked with many such students as a tutor; in other words, many of these students are still seeking help with writing skills. A very small percentage of our school’s classes are able to utilize the fellows program. After all, schools with 30,000+ students like the University of Iowa can hardly be expected to provide a fellow for every 10 or so students for every single class, whether due to the logistics of choosing appropriate classes or issues tracing back to funding. In other words, the Writing Fellows program may succeed at improving equity but only for a small demographic. The challenge for future writing centers then becomes implementing writing-based programs that combine the diversity-driven nature and accessibility of a tutoring program with the special attention and equitable push of the Writing Fellows program.

All this to say that there are exceptions to all of the general distinctions that I have laid out. There is a noticeable gray area in defining fellow-student and tutor-student relationships. While unlike the fellow, the tutor is not always guaranteed a follow up appointment where they may track the student’s progress between assignments, most tutors can expect to see recurring appointments. Some students may even commit to weekly meetings for the entire semester, as is an option in Iowa’s Writing Center. Nor are assignments given to tutors always completely unfamiliar. In fact, most tutors can identify set seasons in which certain assignments will be particularly prevalent. It would be hard to find an Iowa tutor who hasn’t memorized the nursing school application by the time April deadlines role around. It’s difficult to label a writing center tutor a pure generalist when they can restate a Rhetoric writing prompt off the top of their head; the Writing Center tutor will gradually become an expert on certain coursework after only one semester.

We can also see the contradiction between program expectations and reality in the predicted level of student commitment in each program. A fellow may witness drastic differences in student performance in their small batch of class members alone. For example, the final class I fellowed for featured writers on both ends of the effort spectrum. While one student eagerly emailed me a new draft every week, I couldn’t get some of the others to answer my emails the entire semester. Supposedly, one program implies greater level of commitment: “Fellows’ students are obligated to participate in the program, whereas WC tutors’ students sign up for tutoring on a more or less voluntary basis” (Severino and Knight, 2007, p. 23). Yet, as I witnessed time and time again, it is often the perseverance of the individual student that will grow their confidence and capability in writing, along with demographic factors. Seemingly mandated commitment cannot guarantee a greater improvement when students face language barriers, roadblocks that come from being a first generation student, etc. The differences I have laid out illustrate the need to differentiate between the expected outcomes of writing programs and the realities students and writing mentors face daily.

Johnson’s Experiences

Tutoring and Fellowing: Developing Strategies for Similar (yet very Different) Roles

A student walks in for their first meeting in the Writing Center. It’s possible they’re nervous, having had to navigate to the location of the center in a building that most just know from taking GE Rhetoric or Literature. Or perhaps they’re ready to get this meeting over with so they know how to finish up a final draft and turn an assignment in. Maybe it’s somewhere in the middle—a mixture of nervous memories and anticipation, all baked with the fatigue laden in many collegiate academic spaces. Whatever the case, you as a tutor know the students are there because they took the initiative to sign up, and usually, once the conversation gets going, their engagement and interest is focused on making the work they brought in better.

As both a writing tutor jumping from appointment to appointment in a university writing center for two years and writing fellow shifting between classes semester to semester for three years, I have had the pleasure of meeting and discussing student writing at various levels and in various contexts. From PhD students working through data analytics manuscripts for publication, to business students wanting help editing PowerPoint slides to be more concise, to literature and rhetoric students wanting to deepen their analyses, each new assignment I encountered in both my time as a fellow and my time as tutor forced me to grow my mindset to be more receptive and meet the student where they were at. The writing, however, was not the only part of a session requiring my adaptation.

The scene I just described highlights my standard experience of working with students as a tutor in the writing center. An appointment tutor, I was lucky to have a full schedule of students who had signed up, determining for themselves that another perspective from an “expert” could push their work to the caliber they desired. The writing center, to a certain degree, is a writing refuge, a space design where the art and craft of writing commands the orbit of conversation, and, for many, those who work there are masters of this nebulous and subjective space (Runciman, 1990).

Conversely, my schedule as a writing fellow wasn’t always filled with as many adamant or animated students. While I worked as a fellow prior to beginning my time as a tutor in the writing center, functioning as a peer tutor in this role, I was often perceived as a tacked-on element to a course, a requirement the students had to check off to receive credit rather than a service they had sought out themselves. Conversations didn’t have the same grounding in student autonomy, and student engagement in the writing process varied greatly. As a result, this variation in circumstance forced me to generate strategies specifically for my circumstances as a writing tutor and writing fellow; specifically, I considered how to address the differences in student engagement while finding how each peer tutoring experience intersected with one another, forging a wider skill set to be used in both.

Activating Student Buy-In

While it could be easy to point to a supposed difference between appointment tutoring and fellowing in a student’s intrinsic motivation to come into the center versus the extrinsic reward a better grade by participating in the fellowing process, it is hard to generalize about tutored versus fellowed students and their motivations given the diversity of students passing through both programs. Students may enter the writing center for an appointment with the same expectation that their grade should vastly improve because of this single appointment, despite it not being a guarantee. Conversely, students who show up for fellowing appointments may be passionate about the topic they have chosen and thus be invested not just in their grade, but the actual process of their writing’s creation. In balancing students like these, or one with any other motivational makeup, a tutor or fellow may ask themselves this question as they enter each appointment or session: how can I best activate student buy-in into the writing process?

Regardless of a student’s motivation for attending the scheduled meeting, there are still other emotions and feelings that influence a meeting’s overall trajectory. Against normally imagined extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, other factors influence a student’s emotional makeup. In his 2008 speech “What Being a Writing Peer Tutor Can Do for You,” Kenneth Bruffee emphasizes how tutors and tutees are their given roles, and yet so much more than just that at the same time. These other aspects of identity hold varying levels of influence, whether they are visible or invisible within a session, and as a tutor or fellow, we hold the power in many circumstances to recognize or ignore these identities of the students we interact with, thus encouraging or discouraging closer dialogue and rapport. Being cognizant of a student’s emotional status in a writing conference is also highlighted in Dana Lynn Driscoll’s 2020 article “Tutoring the Whole Person: Supporting Emotional Development in Writers and Tutors.” Driscoll highlights the importance of turning students’ negative dispositions toward writing due to past experiences into more positive ones during tutoring, helping disassociate writing from emotions like fear and anger, replacing them with feelings of success. Thus, in both Bruffee and Driscoll, acknowledging the students’ emotions toward writing is not simply about recognition, but how recognizing a student’s background and identities can allow tutors or fellows to make profound changes in students’ motivations and their attitudes about writing. Effectively, the tutoring space—be it in a center for a live-appointment or over a screen for a virtual one—has the potential to be an active transformative exchange.

Forging these kinds of positive experiences, while easily said, in my experience has come from the ability to connect with students in differing ways. As Harry Denny points out in his article “Queering the Writing Center,” building better writers necessitates engagement and understanding of identity—including those of the students we work with (2010). Where can the professional and the personal mix to create an atmosphere that permits a student to ease into writing with curiosity, rather than approaching it with confusion, anger, or frustration?

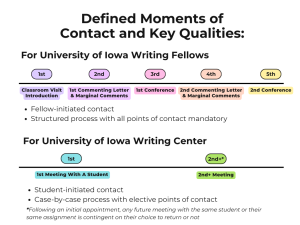

As a result, I became able to define how moments of contact are an essential facet of both tutoring and fellowing. However, in my positions as both a tutor and fellow, along with Writing Center participation being voluntary and the other mandatory, the potential timeline for building a relationship differed vastly. In a typical writing fellows program, where feedback includes not only verbal conferences but commenting letters and comments in the margins, despite only two conferences, the potential ways to both provide feedback and build rapport are greater than with a writing center student, whose only contact occurs during their appointment time. Thus, as a tutor and a fellow, I had to not only recognize this similarity, but identify how moments of contact were different in each process (see Fig. 1); while understanding these differences was a useful incentive for me to outline the various ways in which I could have contact with my students, for any tutor or fellow, being able to dissect the structure of their own program becomes essential. Where can we extend a hand to increase student investment and, as a result, overall impact whether tutoring or fellowing? Once having defined these moments, I considered how to utilize them meaningfully to create a welcoming, encouraging atmosphere and build space for knowing both the writer and the identities behind the writer. While these moments of contact can vary depending on the layout of a particular fellowing program or format of a writing center, Figure 1 demonstrates where I defined moments within the structure of each environment, and Figure 2 showcases how I found I could subsequently capitalize upon such moments to build connection with students. These offer examples of how even within such a short time frame, there are a myriad of ways to connect meaningfully with students, and suggest a possible reflection activity for any tutor or fellow to identify for themselves.

Figure 1

Comparative Timeline Chart Highlighting Moments of Contact and Key Contextual Qualities Between Programs

For a standard writing center conference, the moment the student walks in is full of possibilities for making an impression. While some students come once and others become “frequent fliers,” questions inquiring about the student’s well-being, their background, and figuring how they see themselves in relation to writing have become essential questions in my approach as a tutor. While I utilize many of the same questions for fellowing, the process boasts a greater number of moments where contact can be made directly or indirectly with the student. The student conferences operate in similar ways to the writing center appointments; however, due to the additional review of materials ahead of time, commenting letters and marginal comments become a rich space for both instructing and developing a relationship with students. Letting personality—that is, utilizing tone, vocabulary, and expressions more customary for informal situations—shine through in feedback is one of the best ways I have discovered to connect with students, and to get them to care about investing in the process, alleviating the pressure that comes when navigating rigid, formal expectations. Additionally, given the greater amount of moments within the fellowing process at the University of Iowa, pacing how I provide such feedback becomes more important than in the shorter timeframe of an appointment session. These two philosophies of approach became clear to me participating in both programs at the University of Iowa; however, for any institution—any tutor or fellow—reflecting and defining on personal philosophy fitting within the structure of your program can provide your own writing instruction with a stronger identity.

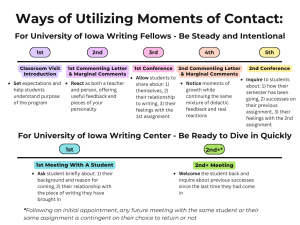

Figure 2

Comparative Chart of Ways to Utilize Moments of Contact Within Both Models of Tutoring

Student Perceptions and Building a Dialogue

The debate over where the boundary between expressing one’s personal and professional personas lies is present in most spaces of employment. How much can we humanize ourselves? What do we feel comfortable sharing with clients/students? How do we steer a conversation leaning toward the limits of our personal boundaries back into the more professional realm? There are many questions that we must answer as writing instructors in negotiating our own professional identities. Undeniably, however, working with humans—persons—demands a greater demonstration of one’s personality than other professions (Denny, 2010). In crafting a professional persona that leans into authentic aspects of their own personality, tutors and fellows can create a mentoring style that forges an environment many writing center researchers deem as beneficial to increasing student motivation and easing anxiety (Bruning & Horn, 2000; Mackewicz & Thompson, 2013). In combining the personal with the professional, writing products, writing processes, and the writers themselves are all taken into consideration. One of the cases this nuanced approach has shown beneficial in my own experience has been working with international students.

During one semester, I worked with a student from Japan on a collection of communications reflections and papers. When she would come into the writing center for the first time, she was reserved and apprehensive in describing her relationship to writing in English—a non-native language for her. During this conversation, I shared about how having lived abroad and having taken higher-level foreign language classes at the college level, I understood the stress of wanting to adhere to grammar rules and different cultural approaches to writing essays while also wanting to express her thoughts authentically and accurately. In sharing this, our conversation continued to grow as she began to divulge moments in which she felt her language on the written page did not actually reflect her thoughts, and after a few moments of conversation about our personal experience with foreign language, we had shifted naturally into discussing her paper, tackling the doubts she faced at the time.

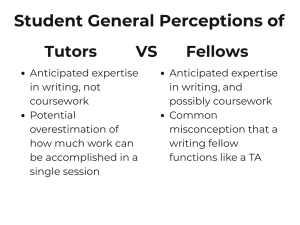

This approach presents a melange of priorities, and communication becomes further nuanced within the short time frame of a student conference or appointment session, and the goal of leaving the student in a more confident position with their writing requires more steps to consider. It is a mindset demanding the flexibility and charisma of customer service while balancing the critical thinking capacity and focus of a teacher. As a result, the unknown expectations that a student in the writing center or in a course with a writing fellow may have of their peer tutor may complicate the way forward (see Figure 3); thus, outlining and reflecting on such influences becomes another commonality between tutoring and fellowing programs, and yet it is equally another moment of contrast. The expectations that a student harbors prior to entering the center or a fellowing meeting, while potentially informing the goals they communicate to a tutor, most likely extend beyond what a tutor or fellow learns at the beginning of the session. Thus, observing, noticing patterns, and preparing yourself as an instructor of writing can facilitate being able to temper these unexpected elements in real time.

Figure 3

Students’ Perceptions of Tutors Compared with Fellows

For instance, a student once made an appointment with me in the center that quickly spiraled away from what most tutors would consider a standard session. Having brought in her personal statement for medical school, the student—a woman of color—informed me that her academic advisor thought her statement needed to be looked at by a writing center tutor to be corrected to conform to standard English grammar and mechanics. The student told me that her advisor had looked at her statement many times and found with each draft that frequent conventional spelling and grammatical errors were a recurring issue; so, as we began to look through the first paragraph of her statement, this expectation she had carried with her into the center developed into something else as I began to explain a couple comma rules and syntax conventions. The student then asked: “Can we spend the rest of our session just reviewing grammar rules?” she asked. Before even diving into her second paragraph, the meeting had abandoned all pretense of focusing on her draft in specific, the student believing the writing center to operate as an instructional space for grammar and punctuation. Moreover, impassioned by her drive to go to medical school and the belief that grammar was the root problem, it was challenging to explain to the student that the writing center didn’t function strictly in this way.

The politics of “correctness” and Standard English conventions and the student’s perception of these issues also dangled in the air. However, she had entered in with expectations influenced by an advisor she respected and had believed the problem to be something easy to point out—able to be remedied quickly if she could be taught these rules. The goal she had for the session, as a result, was not as attainable as she believed it to be. Her actual statement, after all, while presenting these “grammatical issues,” did not necessarily adhere structurally or logically to the genre of the personal statement. So, while she wanted to continually inquire about grammar, I wanted to turn our attention to the structure and investigate how we might paint a clearer picture of who she is. As a result, the conversation oscillated back and forth, and while she walked away with some feedback and other recommendations on how she could study standard grammar rules on her own, the experience did not necessarily match the one she had imagined would take place over our 30-minute session. As her tutor in that situation, I reflected following our session: in what ways do I as a tutor or fellow have to anticipate and be able to redirect—if needed—student expectations.

Student expectations—formed of their own accord or from the advice of others—may, after all, contest the training or procedure developed by a writing instructor during initial training or even after years of experience. These expectations, which influence and act as part of the writing process (Bromley & Regaignon, 2011), oftentimes feed into the goals the student develops and communicates to a tutor. In the case mentioned above, being able to respond to student concerns was a priority; at the same time opening her perspective to higher-order issues was equally important. But, what happens when a student’s goals involve this idea that a tutor can act as a cure-all? That a tutor will be able to completely fix their paper’s grammatical and structural edits within the span of thirty minutes? That a tutor will be an expert on the sources or the content the student might be dealing with? As Laurel Raymond and Zarah Quinn (2012) point out, ignoring student goals can undermine a student’s own authority over their own paper and writing growth, yet tutors often must find a way to lead students unaware of the role of the writing tutor or fellow to both reasonable expectations and goals. For the example above, if I was only able to see the student once in her process of developing a personal statement for medical school, I wanted to center her concerns as much as possible, yet still provide my insight on higher-order concerns that presented themselves to me in her paper. Following this experience, as I continued to work in the writing center and as a writing fellow, I found that students’ perceptions of me differed in each role, and their expectations and questions changed whether they were interacting with me in the writing center or as a fellow in conjunction with a specific class. No two students were exactly alike, yet being perceptive to these expectations, I noticed some patterns.

Students who made an appointment in the writing center saw me as an expert in writing, and rarely did they anticipate I would have knowledge about the content of their drafts. As a result, many students expected the kind of help that the pre-med student wanted: assistance with grammatical edits, formatting, and flow. They want to focus on fine-tuning sentence-level and wording issues, viewing me as an expert in writing rules and conventions. In fellowing, however, students’ expectations inhabited these same parameters and beyond. Operating in conjunction with a particular course and instructors each semester, students saw me as a fellow student meant to assist them with their writing; simultaneously, however, perhaps because they lacked familiarity with the parameters or Writing Fellows program, they often confused the role of peer writing assistant and overall teaching assistant. In conferences, that confusion also resulted in questions about course content and specific instructor expectations. While I never presumed the authority of a TA in my responses, the expectations the students held of me were there regardless; they interpreted my words through one lens even though I was communicating them through another.

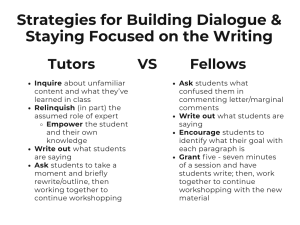

Figure 4

Figure with Suggested Tactics in Each Program That Promote Dialogue, Connection, and Focus on the Writing

Consequently, this variable of student expectations creates an oscillating factor affecting how I could craft a personable environment, while still meeting professional goals and preventing misconceptions from taking control of the meeting’s dialogue. Thus, while permitting students to share and include themselves and their emotions is excellent kindling to ease into conversation, the meeting needs to stay centered on a student’s piece of writing. As shown in Figure 4, developing strategies to keep students writing and utilizing meeting times for both programs was something I had to do. For appointments in the writing center, asking questions about the class and allowing the student to become the expert is a natural way to get students to open up. For writing fellows, asking students in conferences about any confusions or questions concerning the commenting letter and marginal comments does similar work in allowing them to open up and showcase that you are acting as a guide—not a strict authority figure. In other instances for both programs, writing out what a student is saying and reflecting it back to them can be a way to help students see the relationship between how they verbalize their thoughts and how that appears—and can be reshaped—on paper. Regardless of program, in developing these strategies that keep conversations focused on writing, they promote for students in the center and in a fellowing conference to take leadership within a meeting. This act of taking ownership over their writing or knowledge of class material can boost confidence, create a meaningful and empowering conversation, and produce a student more motivated to continue working on their writing post-meeting.

Conclusion

In detailing the thoughts and perspectives of two peer tutors who have served in two separate roles as both writing center tutors and writing fellows, we have examined the two positions for their differences but also for their similarities and the ways they overlap on an observational and practical level. Examining our roles in such detail opens a gate to understanding how the skills acquired within each program can flow across various tutoring spaces.

A tutor and fellow both have the power to create an atmosphere where student motivation can grow, even out of mandatory appointments. Both tutoring and fellowing share limited points of contact in which to build rapport; therefore, how quickly a tutor or fellow utilizes these points of contact matters a great deal. Another key skill tutors and fellows need is the ability to articulate to students the functions and limits of tutoring/fellowing. Misguided perceptions can be remedied quickly by communicating clear and positive expectations that set the student on the path toward being a stronger writer with a strong text.

For, while they are different programs furnishing contexts that demand different tutoring tactics—as well as each having its own benefits and drawbacks for both student impact and tutor effectiveness—it is our belief that peer tutors in any capacity can develop a more nuanced and adaptable skill set when asked to analyze the contextual framework that governs their tutoring sessions. Specifically, in comparing two different programs from both observational and practical standpoints, the conversation expands to demonstrate how even within a single university writing center, program differences demand varied training. In defining these differences on a macro level, emerging micro differences can further complicate the comparison/contrast between programs and individual tutoring strategies. These micro differences, which we have detailed here, demand the need for a continual dialogue within individual programs and the tutors that work within them.

For us, reflecting on this process revealed a clear overlap of the ways each program can train tutors and fellows to adapt to various student interactions; it equally showed how structural differences and design choices of a program impact the starting line that these interactions begin on and potentially the trajectory that a tutor or fellow is able to set these interactions on. Having tutored and fellowed in both programs, it is clear to us that for tutors and fellows to function to their best ability, they must reflect on these structural qualities and translate them into practical questions: how do you tackle a paper in a subject you don’t specialize in? What does building trust look like? How exactly do you explain your role briefly to clarify misconceptions and set expectations for a session?

Finally, having discussed each program’s parameters from individual perspectives, we recommend that tutors and program directors interrogate how both fellowing and appointment tutoring serve varying purposes for a writing center. Thus, our discussion can serve to launch more reflection, problem-articulating, and problem solving about experiences had for tutors in either or both of the two programs, especially in defining their individual role and purpose.

References

Bond, C. (2020). Leveling the playing field in composition? Findings from a writing fellow pilot. Southern Discourse in the Center: A Journal of Multiliteracy and Innovation, 24(2), 37–60.

Bonevelle, M. (1997). Integrating student expectations into writing center theory and practice. [Master’s Theses, Eastern Illinois University]. EIU Campus Repository. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1815

Bromley, P. & Regaignon, D. R. (2011). What difference do writing fellow programs make? The WAC Journal, 22, 41–63. https://wac.colostate.edu/journal/vol22/regaignon.pdf

Bruffee, K. A. (2008). What being a writing peer tutor can do for you. The Writing Center Journal, 28(2), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1700

Bruning, R., & Horn, C. (2000). Developing motivation to write. Educational Psychologist. 35(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_4

Dinitz, S., & Harrington, S. (2014). The role of disciplinary expertise in shaping writing tutorials. The Writing Center Journal, 33(2), 73–98. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1769

Denny, H. (2010). Queering the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 30(1), 95–124. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1528

Driscoll, D., & Wells, J. (2020). Tutoring the whole person: Supporting emotional development in writers and tutors. Praxis, 17(3), 16–28. http://www.praxisuwc.com/173-driscoll-wells

Kiedaisch, J., & Dinitz, S. (1993) “Look back and say ‘so what’”: The limitations of the generalist tutor. The Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1286

Smithgall et al. (2025). Becoming Writing Fellows. TPR, 9(3). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/becoming-writing-fellows-program-logistics-and-research-informing-practice/

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2013). Motivational scaffolding, politeness, and writing center tutoring. The Writing Center Journal, 33(1), 38–73. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1756

Raymond, L., & Quinn, Z. (2012). What a writer wants: Assessing fulfillment of student goals in writing center tutoring sessions. The Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1855

Runciman, L. (1990). Defining Ourselves: Do We Really Want to Use the Word “Tutor?” The Writing Center Journal, 11(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1220

Severino, C., & Knight, M. (2007). Exporting writing center pedagogy: Writing fellows programs as ambassadors for the writing center. In W. Macauley & N. Mauriello (Eds.), Marginal words, marginal work? Tutoring the academy in the work of the writing center (pp. 19-33). Hampton Press

Severino, C., & Trachsel, M. (2008). Theories of specialized discourse and writing fellows programs. Across the Disciplines, 5(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.37514/atd-j.2008.5.2.04

US News and World Report. (2023). 2024 colleges with great writing programs | US News Best Colleges.