Nora Hoffmann, Goethe University Frankfurt

Translated by

Saurabh Anand, University of Georgia

Pam Bromley, Scripps College

Nora Hoffmann, Goethe University Frankfurt

Andrea Scott, Pitzer College

Preface

To encourage our colleagues’ engagement with the wide-ranging scholarship that has emerged from writing centers (WCs) in German-speaking countries, we present a translation of Nora Hoffmann’s 2019 book chapter on the state of writing centers and writing center research in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.[1] WCs in this region, which also includes Luxembourg, are some of the oldest and by far the most numerous outside of North America (Bromley, 2023; Bromley et al., 2021). Because in most European contexts, “the writing center is the writing program” (Santa, 2009, p. 3), WC work in German-speaking countries offers U.S.-based practitioners and beyond a model for broadening their missions to more fully encompass writing across the curriculum (WAC) and writing in the disciplines. In a context without first-year or other required writing courses, where funding priorities regularly shift, colleagues in this region are arguably more likely to have created “embedded” WC programs; such programs advance WAC priorities through the WC (Gladstein & Regaignon, 2012, p. 38), supporting writing processes and pedagogies for students, staff, and faculty in diverse ways (Scott, 2017a; 2017b). That is, since the 1990s, WCs in German-speaking countries have advanced research and practice in a very different context, developing new and useful approaches that merit attention outside of Europe.

However, much of this work remains inaccessible to English speakers. This is the result of common assumptions of U.S.-based practices and English monolingualism in U.S.-based writing studies publications (Horner et al., 2011), though this is changing (Hutchinson & Perdigón, 2024). We recognize the very real challenges when sharing work written in one language and context with another, including the difficulties of making legible place-based pedagogies and concepts (Anand, 2025; Horner et al., 2011).

Hoffmann (2019) examines the work and research of writing centers in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, with Germany having the largest population and number of university students as well as WCs. Her study was conducted at a key moment: five years after a substantial increase in the number of writing centers, stemming from a German federal government grant [Qualitätspakt Lehre]—funding that would disappear in 2020. Translating this 2019 piece (with 2017 data) allows us to share with a U.S. readership the state of Germanic writing studies and WC research at a very important time, as the field was seeking to define itself, its importance, and its work to the broader university community in light of a looming funding gap.

In translating this text, we encountered a number of terms and concepts that we found crucial to clarify in order to facilitate cross-linguistic writing center knowledge for U.S.-based readers. We found particularly generative the work of translation scholar Venuti (2017), who recognizes such conundrums as valid and productive moments to confront “foreignness” in Hoffmann’s text. It was important to us to make sites of difference legible in our translation, as part of our broader commitment to center writing center scholarship coming from outside a U.S. perspective. Perhaps most importantly, key terms are understood differently, most notably WCs and writing programs. As will be familiar, in the U.S., WCs most commonly provide individualized consultations conducted by peer tutors (National Census on Writing, 2013; Writing Centers Research Project, 2023), while WAC programs typically promote faculty development and writing across the university, such as through writing-intensive courses (National Census on Writing, 2017b). In contrast, WCs in German-speaking countries not only provide student-focused writing support but also support faculty and staff in teaching writing across the curriculum and in the disciplines (Scott, 2017a). From a U.S. perspective, it might seem more peculiar for WCs to be charged with what is typically considered writing program work, focused on teaching and faculty development, but that is common in German-speaking countries. We note a few other differences in key terms in designated translators’ notes inserted as endnotes in the text below; we also provide key updates and relevant German terms in square brackets. All other endnotes are the author’s original, in translation.

WCs in German-speaking countries, like many writing centers at small liberal arts colleges, very often function as writing programs—that is, they comprise both the student-focused and curriculum-focused structures of writing on campus (Gladstein & Regaignon, 2012). In the regional context, as we see in Hoffmann’s work, it is common for individual consultations, as well as workshops and other activities, to be offered by professional staff, instead of, or in addition to, peer writing tutors (Bräuer & Girgensohn, 2012). 63% of WCs in Germany offer tutoring with professional staff and 72% offer peer tutoring (Hoffmann & Freise, 2024). While writing program administrators in the U.S. generally have a graduate degree in English or Rhetoric and Composition (National Census on Writing, 2017a), WC staff in German-speaking countries come from a wider variety of disciplines, the most common being social sciences; German language, literature, and didactics; German as an additional language; and linguistics. While writing studies [Schreibwissenschaft] is an emerging and dynamic field in the region (Huemer et al., 2021), there is no disciplinary equivalent of rhetoric and composition–and therefore no established discipline–for WC experts to join in German-speaking countries.

Perhaps as a result of this difference in structures, WCs in German-speaking countries have re-imagined programs and launched new types of events. For example, universities in the region have reworked writing fellows programs at key moments to fit with ongoing changes to their institutional contexts (Hughes et al., 2023). A key innovation that began in Germany in 2010 and has been adopted worldwide is the Long Night Against Procrastination, where, at a deadline-heavy moment in the term, WCs stay open late (or at least later) to provide individualized support and a wide variety of activities to keep writers motivated and engaged (Girgensohn, 2012; Kiscaden & Nash, 2015).

Finally, a note about our process. The translators first asked Dr. Hoffmann if she would be interested in having this chapter translated. Once she agreed, the translators asked how involved she would like to be and included the author in the request to the original press for permission to publish a translation. The translators then got to work, first settling on translations for key terms and then arriving at a complete translation; two of us used Deepl and one of us used Google Translate to arrive at an initial translation and/or double-check formulations. In reviewing the draft, the translators noticed several places where they were unsure about what exactly was meant by some key terms and phrases, requiring some synchronous and asynchronous exchanges, working in English and German, between authors and translators to ensure quality and accountability of translation (Baker & Maier, 2011). In this process, our quartet discovered that some of our assumptions about terminology and staffing were not quite right, even though the team has considerable expertise in both contexts; we’ve included some of this reflection in our translators’ notes.

We also recognize the significance of translation as a means of translingual research engagement. In our experience, we found translation to be a largely unutilized research method that enhances access to knowledge across different languages and promotes further reflection on key concepts.[2] Translation not only preserves the diversity of writing center concepts in a particular locality but also facilitates the exchange of meaning among writing center professionals from other language communities. Translation enables the incorporation of multiple linguistic perspectives within academic discourse, promoting context-specific writing center epistemologies. This contributes to what is yet to be recognized as valid writing center knowledge, providing a glimpse of multilingual administrative labor (Anand, 2024). Scholarly translation makes research, literature, and academic findings available in multiple languages, ensuring that knowledge is not confined to dominant languages.

We, therefore, suggest a collaborative approach to translating writing studies’ work, grounded in expertise in both contexts and back-and-forth translingual conversation. While we recognize that AI tools are getting better all the time, we still believe that, as human translators, we were able to unpack linguistic and contextual WC knowledge in a more reflective and nuanced way. This, in turn, promotes the kind of collaborative translingual negotiation across national contexts that we believe human-based translation as a method is particularly well-positioned to do. Hence, we think the resulting translation is worth the effort. This piece highlights work happening in one context for an audience in a different context, which in turn expands our collective understanding of what WC work can and does look like. We encourage readers to seek out Hoffmann and Freise’s most recent work in English examining the wide variety of writing support entities at German universities which builds on this key piece (Freise & Hoffmann, 2025); there are also pieces that detail other aspects of this study in German (Hoffmann & Freise, 2024; Hoffmann & Freise, 2026).

We are delighted to share with TPR readers this piece as key background reading to more fully understand the important writing studies work happening in German-speaking countries.

Translators’ Response to TPR Policy on Author Use of AI (Including ChatGPT)

DeepL and Google Translate were used to double-check formulations and verify comprehension of syntactically complex sentences. As non-professional translators, we also gathered suggestions generated by AI to help support our translation process.

In rendering our translation, we stayed as close to the original text as possible, in an effort to preserve the voice and style of the article in the German original. It was important to us to make the research intelligible to an English-speaking audience, while also preserving the linguistic differences that are the hallmark of place-based forms of writing center research.

Abstract

This contribution analyzes the current state of and conditions for writing center research in German-speaking countries and points to future possible directions. It addresses the following key questions: 1.) What kind of work do writing centers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland engage in? As a result, what fields of inquiry lend themselves to writing center research? 2.) Under what conditions is research possible at writing centers? 3.) And, given the responses, what is the current state of writing center research? In order to answer these questions, the online presence of 70 writing centers was surveyed. In addition, a review was conducted of empirical and theoretical research on writing centers published in disciplinary journals and edited collections between 2012 and 2017. After presenting the results of web-based searches and a literature review, desired outcomes and future paths for writing center research are discussed.

Keywords: Transnational, multilingualism, internationalization, translation, German-speaking writing centers

Introduction

In 2012, Girgensohn and Peters, invoking the U.S.-based field of writing center research (WCR), argued to establish a European “Schreibzentrumsforschung” [writing center research], in order to make “informed claims about the value of our work” (p. 2). They offered the following definition:

Writing center research is concerned mainly with what happens in writing centers: it studies the interventions of writing pedagogies such as consultations and explicit teaching in order to generate knowledge about their impact and about learning and writing processes. (Girgensohn & Peters, 2012, p. 3)

Much has changed since the early 1990s, when small working groups first emerged that were dedicated to the teaching of academic writing (among other things).[3] Today a research community has developed that is widely networked. Since the 2000s, possibilities for exchange and publication have increased through professional organizations,[4] professional development opportunities,[5] conferences,[6] journals, and writing studies series.[7]

Nevertheless, Girgensohn and Peters (2012) discovered at the time that there was a paucity of explicit WCR being conducted–not just in German-speaking countries, but throughout Europe. They identified only eight theoretical and three empirical contributions to date. How do things look in 2017, five years after their official call for WCR and the doubling of the number of German WCs through the federal funding project Qualitätspakt Lehre [Quality Pact for Teaching] (QPL)?

This contribution attempts to identify preliminary trends. To this end, it draws on a website and literature review based on the following questions:

- What kind of work do writing centers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland engage in? As a result, what fields of inquiry lend themselves to writing center research?

- Under what conditions is research possible at writing centers?

- And, given the responses, what is the current state of writing center research?[8]

The web-based review conducted in August 2017 comprised WCs included on widely circulated lists and in influential representations at that time.[9] A total of 70 WCs were included, 57 of which were located in Germany, eight in Austria, and five in Switzerland. Although this pragmatic approach means that the study fell short of a full survey,[10] the large number of WCs included offers an adequate overview of basic trends in German-speaking countries.[11]

To answer the first key question of this contribution, the study examined the offerings posted on each website. This was necessary in order to avoid making assumptions based on the practices of well-researched WCs situated in the U.S. Arguably, WCs in German-speaking countries operate within a context that differs significantly from the U.S. in terms of the higher education system, the status of writing and its instruction, and the culture of writing on campuses.

To answer the second key question, the team and staff pages were analyzed to determine the size and disciplinary expertise of each center’s personnel. In addition, we took into account how the WC represented itself, systematizing information about its self-understanding, financing, and founding.

To obtain an answer to the third key question, a literature review was conducted for the period from 2012 to 2017. Relevant disciplinary journals (Journal für Schreibwissenschaft [Journal of Writing Consultations] [JoSch], Zeitschrift Schreiben [Journal of Writing], Journal of Academic Writing) and edited collections were considered. Additional sources were located and included by researching WC-websites listing the center’s publications. The aim of the literature review was to gain an initial sense of the state of WCR by analyzing publication venues that are presumably consulted often. For practical reasons, a complete overview of the literature was not attempted. This would have required including numerous contributions from adjacent fields, especially the scholarship of teaching and learning, applied linguistics, and foreign language didactics.[12]

Both empirical and theoretical research contributions were sought out for the literature review. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were classified as empirical. Publications were included in the more loosely defined category of theoretical research when they transcended the strictly anecdotal, definitional, or practical to offer a theoretical concept or approach to WC work with implications that stretched beyond the individual case described. In addition, approaches to applying theoretical concepts from other fields to WC work were included. Further clues for classifying theoretical contributions were drawn from articles that were organized under headings or tables of contents as theory or research contributions, even though anecdotal reports were occasionally situated there. Altogether 140 publications from the timeframe were classified as WCR, of which 85 were empirical and 55 were theoretical. To gather information about the authors’ disciplinary backgrounds, published author biographies were analyzed or found online–in addition to the content of the articles–in cases where the information could not be found elsewhere.

The results of both searches of the WC websites as well as WCR publications are discussed in the rest of this article in relation to the three key research questions.

Question 1: What are the areas of responsibility of WCs and, subsequently, the objects of WCR?

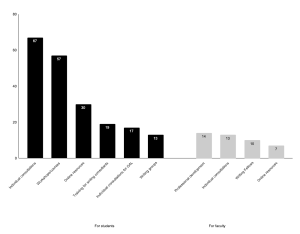

Figure 1

Areas of responsibility in WCs

Note. (N = 70)

Although WCs in German-speaking countries differ significantly from one another in their institutional structure and the range of their activities, the majority nonetheless share several core responsibilities (see Figure 1). The most important of these are individual consultations for students, which are offered at 67 of the 70 included WCs. In contrast to the U.S., where the use of peer tutoring as a form of collaborative learning predominates (Scott, 2017, p. 47), consultations are often also offered by professional WC staff (see Figure 1).[13] Their primary goal is to support individual writing processes. In addition, 17 websites advertise specialized individual consultations for students who speak German as an additional language.[14] Workshops and courses for students constitute a second core responsibility: these are described at 57 of the 70 WCs. All other areas of responsibility are less consistently represented, although it is worth noting that roughly half the WCs host online materials. Periodic events like the Long Night Against Procrastination, among others, were not classified as separate offerings, since it was assumed that they largely include modalities like writing consultations and workshops. The task of training-the-trainer, which requires a high degree of professionalization within a WC, is assumed by 17 WCs for writing consultants (e.g., a tutor education program) and a total of 21 WCs offer several initiatives for faculty (e.g., faculty development). The rapid spread of Writing Fellow programs speaks for the popularity of this modality for supporting the teaching of writing in the disciplines. In 2017, there were already 10 Writing Fellow program sites after the widespread model from the U.S. was first adopted by WCs in Frankfurt am Main and Frankfurt Oder in Germany.

Taken together, all of these areas point to a broad spectrum of activities and contexts that can be researched, that intersect with different fields of inquiry (e.g., language didactics, psychology, education, and the scholarship of teaching and learning) and that are difficult to separate into discrete categories. In order to understand the impact and conditions for success in WC work, additional research is needed that does not simply analyze the activities of WCs in isolation, but rather brings into holistic view their foundations (i.e., constructs of writing competence and its development) and conditions (i.e., prior influences on the development of writing competencies across a course of study). To this end, this article understands WCR as the systematic acquisition, documentation and distribution of new empirical or theoretical findings about the work of WCs, including their contexts, objectives, structures, processes and impact, using scholarly methods. Its goal is to monitor the impact, shape the direction, and optimize the work of WCs, supporting their recognition and institutionalization. Situated in the field of writing studies,[15] its particular focus is WC work.

Question 2: Under which conditions is research possible at WCs?

Such a field of research so diverse in its questions and possible points of entry cannot and should not be carried out exclusively by WCs. WCR is a promising area of research to which numerous disciplines can contribute their diverse expertise and methods. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that WC staff have the motivation and opportunity to become active in this research field given that WCs have gained visibility and become established only in the last few decades in German-speaking countries. In this section the disciplinary experience this professional group brings with it and the conditions under which its research is possible are analyzed. To this end, the results of internet searches of the online presence of WCs in German-speaking countries are relied on.

Of interest is which disciplinary backgrounds WC staff possess that enable them to conduct theoretical and empirical research. To this end information was extracted from the team and staff pages of the WC regarding the major degrees earned by professional staff (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Disciplinary backgrounds of WC staff

Note. (N = 93)

Among the WC staff above, 65% have studied humanities. Within this humanities group, 25% focused on German, 17% on foreign language teaching/research, and 7% on linguistics. These numbers also indicated the necessity of linguistic and language teaching expertise as skills for WCR. Moreover, 30% of the WC staff held degrees in social sciences, providing them a foundational knowledge of empirical research methods. Meanwhile, 3% of the WC staff studied STEM subjects (mathematics, computer science, natural sciences, technology), and only 2% studied law.

Knowledge of writing didactics[16] is important for WCR. However, it is not possible to make a reliable statement about the backgrounds of WC staff in this area on the basis of internet research alone. Only 22% of WC staff have formal training in this area according to their academic profiles, but it cannot be ruled out that others have also completed this without naming it.[17] However, the finding that some universities seem to pay more attention to such qualifications than others is revealing, as at 14% of the WCs, all WC staff have writing didactics training, while at 38% of the WCs, no WC staff list any. An uneven distribution in qualifications at different WCs is therefore likely.

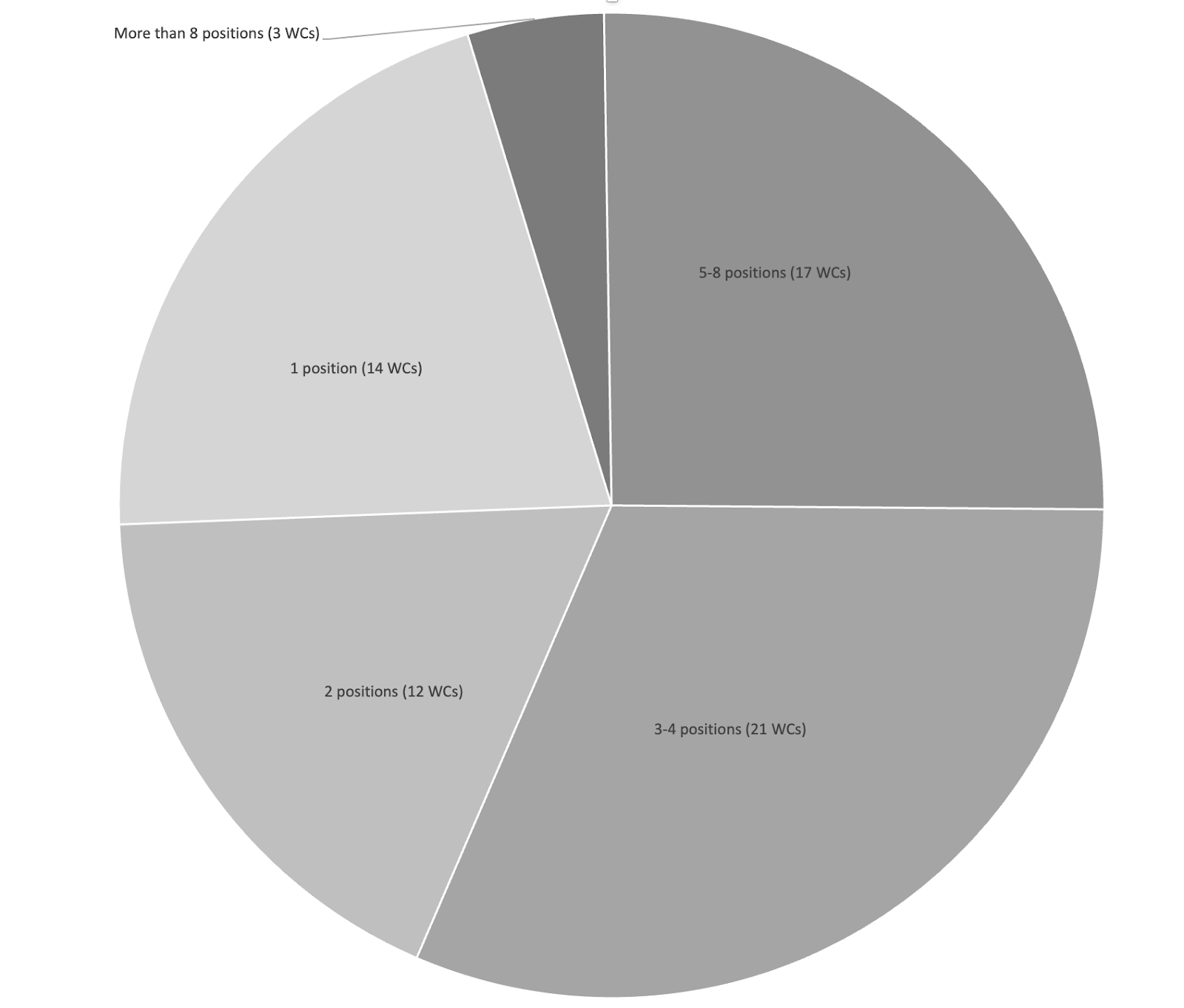

Figure 3

Staffing at WCs

Note. (N = 93)

This research also examined the staffing composition at various WCs to see the extent to which they could conduct research beyond daily operations (see Figure 3). While the specific status of each staff member as full- or part-time was not available online, Knorr (2016) indicates that part-time positions, usually 50% to 75% of a full-time position, are standard. This arrangement of part-time roles often leads to WC professional staff having additional jobs elsewhere (Kreitz et al., 2019). If WCs with only one professional staff member also have part-time positions, many likely could not have been able to engage in research.

Currently, 41% of WCs have one to two staff members, while 29% have more than four, allowing for research capacity. The Writing Center at Alpen-Adria University, Klagenfurt, has 21 staff members, but not all are dedicated exclusively to it. Here, as I was informed in a phone call, faculty teach single courses and/or workshops in the WC. Of the 18 faculty situated in the disciplines at Bielefeld University, 15 are responsible for subject-specific writing support within the project Strengthening Literacy Competencies in Different Disciplines. This situation is similar at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, where a director and nine faculty members also teach WC courses.

The familiarization period in WCR and in special tasks within a WC must also be considered, and long-standing experience is likely beneficial for addressing research projects. Therefore, the timeline of WCs’ establishment was recorded. The writing laboratory at Bielefeld University and the Ruhr University Writing Center at Bochum were the first two pioneers in the 1990s. Between 2000 and 2011, additional WCs were established at a rate of one to four each year, resulting in 19 WCs by 2011. In 2012, this number more than doubled, with 26 new establishments funded by QPL. In the following years, one to three WCs were established each year. As a result, 36 WCs have existed for five years or less. These numbers depict that these centers are only now becoming sufficiently oriented in their field to engage in research projects effectively.

Since 2012, many new WCs have been established, and existing WCs have expanded too, both mainly through QPL funding. Currently, 34% of WCs are fully funded by QPL, 9% receive partial funding, and 57% rely on other sources. It needs to be clarified whether the funding structure or its source type impacts research activities and to what extent. On the one hand, temporary job prospects, such as those in short-term QPL projects, often lead to high staff turnover, resulting in a loss of expert staff and new staff frequently taking time to adjust. This current situation discourages the staffs’ ability to deeply commit to research and take up long-term projects. On the other hand, the short-term nature of the projects can lead to WC staff committing themselves to use research to prove the benefit and necessity of their work to increase the chances of continuing it after the end of the funding period.[18]

The research recorded how important WCs considered showing their own research in external presentations. Most WCs, even those adequately staffed, excluded information about their research activities on their websites–not even on the subpages of individual WCs. However, most focused on service functions. In line with the results of the survey by Kreitz et al. (2019), in which only 15% of respondents from the area of university writing didactics named research as one of their activities, only eleven WCs (16%) had a dedicated research section on their websites, with eight detailing significant research projects, publications, and lectures. These eleven WCs had at least three WCS, and five WCs were led by professors—two in German as an additional language, two in applied linguistics, and one in cognitive psychology. In contrast, none of the remaining 59 WCs without research information were headed by a professor. This data unsurprisingly highlights that connections to a professorship lead to better research opportunities, with significant differences among the WCs.

Question 3: Where does WCR currently stand in German-speaking countries?

Girgensohn and Peters were not the only ones to point out WCR activities and hint at the need for more research in 2012. In 2016, Kruse et al. made a similar observation, noting “deficits in research” and calling for more “basic and practical research” (p. 12 f.). Moreover, the 2016 research handbook on empirical writing didactics does not include a section on WCR. The only relevant article mentions the lack of WCR on the impact of writing didactic measures and the contextual factors affecting academic writing development (Schindler, 2016, pp. 113, 119).

However, this view of German-speaking researchers is contrasted by a much more positive view through an outside perspective of a U.S. WC director. According to Scott (2016), German-language WCs are:

at the very center of disciplinary conversations about writing, driving much of the research on writing and writing pedagogies published in German. Likewise, research in this region presents a language for rescuing the value of practice at a time when scholars in the U.S. are quick to dismiss–often uncritically–local knowledge as they foster empirical research cultures. (p. 1)

The German-speaking writing didactics community is often criticized for lacking solid WC research, but Scott (2016) argues that their practical experience offers valuable insights, especially compared to the heavy empiricism found in the U.S. Nonetheless, there is no consensus on whether WCs should lead research in the field of WCR. Scott (2017b) notes that German-language writing studies “remains largely unknown outside national borders” (p. 43), indicating this issue persists within its boundaries. To clarify, the current state of research results from a literature search covering 2012 to 2017 are presented below.

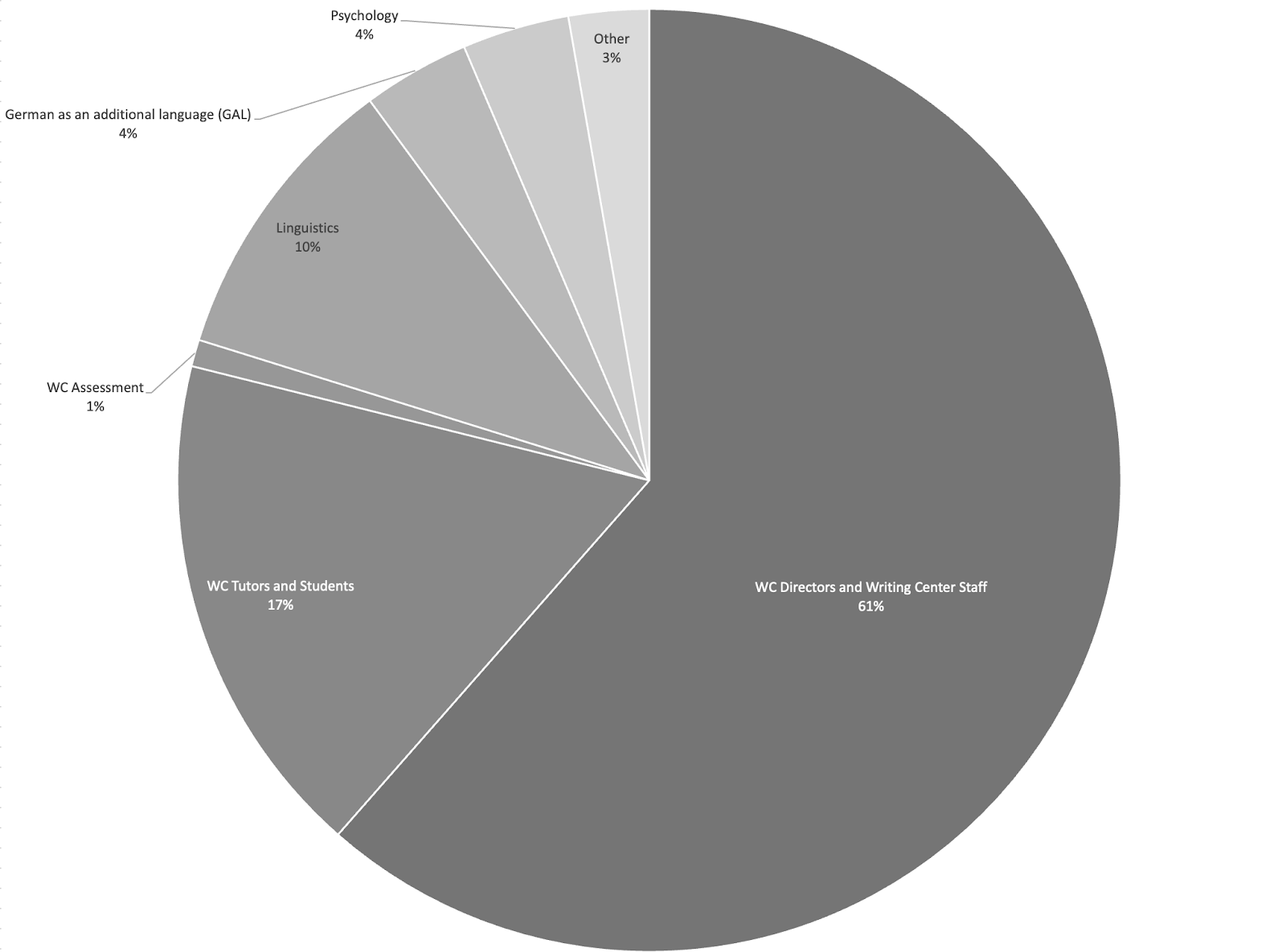

Figure 4

Academic background of authors

Note. (N = 189)

With that background, the research then began identifying the groups publishing on the WC topic by reviewing author information in publications and conducting online research when necessary (see Figure 4). For authors affiliated with WCs, their original professional backgrounds were not considered. At the same time, others were categorized based on the subject area. This study combined WC tutors and students into one group due to difficulties in determining their current or past affiliation with WCs. This analysis showed that the majority of contributions to WCR, at 67%, come from WCs. Following the suggestion formulated by Girgensohn and Peters (2012) to motivate students and WC tutors to conduct WCR following the example of the U.S., at least 10% of the authors were student authors. Even though this is a relatively small proportion, it can be considered a significant number for WCR, given students’ low research publication rates in the German-speaking world: institutional research and assessment professionals contribute only 1%, compared to typical collaboration practices in the U.S. (Schendel & Macauley, 2012; O’Neill et al., 2002). Researchers outside WCs are most commonly applied linguists at 11%.

Figure 5

Publication locations

Note. (N = 140)

Another area of interest this study pursued was the venues where WCR is published (see Figure 5). A significant 58% of research contributions are published in edited volumes, limiting their accessibility and recognition compared to established open-access research journals. Additionally, only 6% appear in journals from related fields like applied linguistics and 5% as standalone online publications, further reducing the visibility of WCR for WC staff and administrators. This study examined three WC-specialized journals (JoSch, Zeitschrift Schreiben, and Journal of Academic Writing), where 22% of research articles were published, alongside praxis-oriented contributions. This scattered distribution hinders the development of a cohesive WC scholarly discourse. Moreover, a survey study by Stahlberg et al. (2019) revealed that 54% of respondents feel that there are insufficient publication opportunities for writing didactics and research in Germany. Thus, there is a clear need for dedicated WC research journals.

It was assumed that, due to the pressure of justification and the increasing professionalization of the field in recent years, research activity as a whole and the proportion of empirical research in particular has increased. However, these trends do not appear to be of a fundamental nature. Numerous empirical studies were already available in 2012, and there was a slight decline in empirical research in 2013 and 2014. In 2017, the anthology by Brinkschulte and Kreitz possibly heralded a change towards more empirical research, as there are now numerous suggestions for qualitative WCR.

During the above period analysis of 2012-2017, 39% of contributions were theoretical and 61% empirical. Of the empirical contributions, 49% were qualitative, 19% quantitative, 19% linguistic, and 13% mixed methods studies. This data shows qualitative analyses are the preferred approach for WCR,[19] which seems consistent, as currently WCR is only starting, so there is a need for a first development of research models and hypotheses.

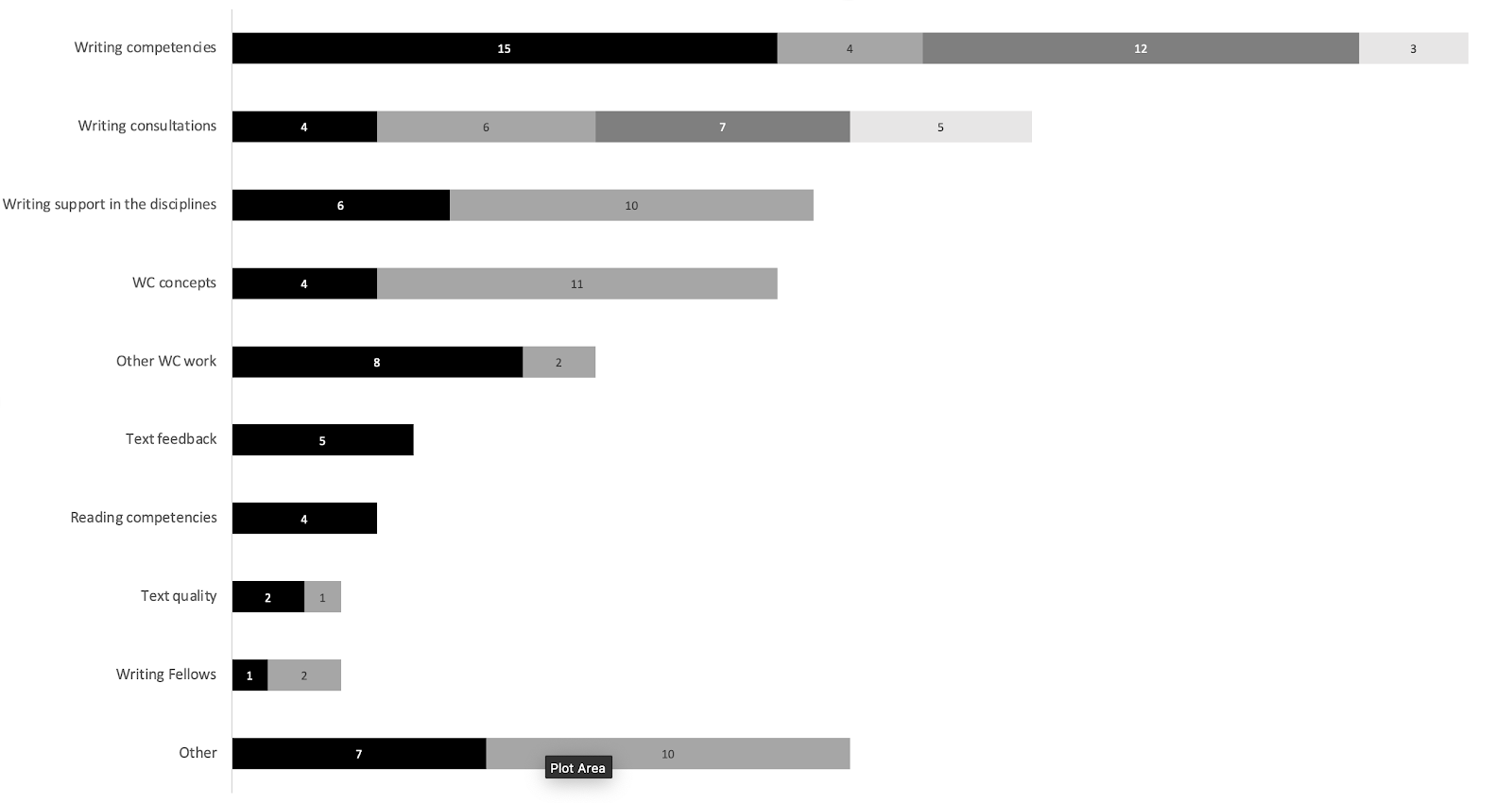

Figure 6

Research areas

Note. (N = 140, of which 8 are double-coded)

The studies were categorized based on their content backgrounds, with some appearing in multiple areas (see Figure 6). Studies cover a wide range of topics relevant to WC work, focusing on both specific activities (see Figure 1) and founding concepts. The main emphasis is on writing skills, followed by writing advice, which is the primary nature of WC work. A considerable amount of research on writing skills and advice is focused on supporting those for whom German is an additional language. However, the high amount of research on this topic does not correspond to the proportion of writing advice targeted to this group, who in any case regularly use regular writing consultations for domestic speakers of a language (German in the case of this educational context). It is more likely because numerous WC staff and five professors who lead WCs have academic backgrounds in foreign language teaching and linguistics. In third place, there are studies on research methods, which show that the basic research called for is being addressed and research instruments are being developed. A total of 15 studies focus on conceptions of WCs, showing that examinations of this work have begun. The 16 publications focused on writing development in the disciplines highlight an increasing tendency to focus on subject-specific writing and using writing to acquire specialized knowledge while also enhancing interdisciplinary writing skills that focus on the writing process.

What could WCR benefit from next?

There is still a need for further research on several underexplored aspects of WC work. Such initiatives could include research and development of writing courses, online materials, Writing Fellows,[20] individual writing exercises, writing didactics training for lecturers, and writing tutor training. Textual analysis is another area that requires more attention. Such research could provide valuable insights into textual characteristics and the feedback and revision processes of the writers.

Additionally, investigating students’ writing and reading skills and their development during their studies would help tailor WC initiatives to their needs across institutions and backgrounds. Evaluating existing writing skills and ways to promote them are also noteworthy. Finally, studying the working conditions and success factors of a WC can improve its overall effectiveness.

To accomplish the above, a thematic theoretical foundation will be essential for effective and efficient German language-based WC work and the WCR. While many concepts from the U.S. have been adopted in German-speaking countries (Dreyfürst and Sennewald, 2014), there are many unexplored theories that could be beneficial (Scott, 2017). Although not all theories may be transferable due to various socio-cultural and educational variations, discussing them could enhance theoretical development and promote integration with related fields, such as writing pedagogy in K-12 education, linguistics, psychology, and adult education.

The Special Interest Group, Writing Research, has made progress in theory formation and establishing a standard reference, representing the German Society for Writing Didactics and Research (gefsus). They created a position paper that defines the academic writing skills students should have upon graduation from German-speaking universities (gefsus, 2022). It is modeled after the Outcomes Statement for First Year Composition from the Council of Writing Program Administrators in the U.S., which has been influential since 2000 (Schendel & Macauley, 2012; O’Neill et al., 2002). This approach has set standards for writing curricula, teaching methods, and evaluations, significantly advancing the U.S. WCR context. Previously, progress was obstructed by complicated definitions of academic writing (Behm, 2013; Harrington et al., 2005; White et al., 2015). Whether the German-language counterpart will as effectively serve the German-speaking world remains to be seen.

To improve research efforts, it is essential to consider the working conditions and professional backgrounds of WCS. With limited time flexibility and only one-third qualified in social sciences (see Figure 2), WC staff can only occasionally handle long-term empirical research independently with multiple contingencies. Therefore, collaboration with WCs, evaluators, and external researchers is a practical solution. The WC literature search shows this is already happening: 66% of articles were written by one author, 17% by two, and 17% by more than two authors. Additionally, involving students in research, which is starting to occur, could further enhance these efforts.

However, the degree to which empirical research conducted by non-empirical researchers can meet quality standards is questionable. Flexible methods and standards for WCR, or the development of standardized methods and instruments, could be ways to conduct WCR in German-speaking contexts. As the WC field is still developing, standard methods currently seem obstructive in limiting possible developments through such restrictions. Moreover, standardized tools may not effectively address the varied writing didactic strategies aimed at improving writing competence. The writing didactics community must tackle the challenges faced by empirical researchers and can learn from the discussions within the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning movement regarding quality assurance in research conducted by non-experts (Huber, 2014).

Finally, another organizational aspect is that a systematic recording of WCR in a separate database would be helpful. An up-to-date annotated bibliography on WCs so far is long overdue, especially since the last one was 18 years ago (Ehlich et al., 2000). It would also be advantageous to establish special journal issues for WCR to demonstrate WC contributions in more academic discussions. Such steps will certainly help promote WCR, which has not yet been fully recognized even within its community, to achieve the visibility, accessibility, and opportunity for mutual development that it deserves, given its promising beginnings.

References

Anand, S. (2024). Defining and learning about multilingual linguistic and professional labor in the writing center context: An autoethnographic tutor perspective. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 21(2), 15–25. https://www.praxisuwc.com/212-anand

Anand, S. (2025, March 11). Discontented with just Western consent: A global Anglophone perspective on writing center professionalization via global rhetorical traditions. Another Word. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/discontented-with-just-western-consent/

Baker, M. & Carol, M. (2011). Ethics in interpreter and translator training: critical perspectives. The Interpreter and Translator, 5(1), 1–15.

Becker-Mrotzek, M., Grabowski, J., & Steinhoff, T. (Eds.). (2016). Forschungshandbuch empirische Schreibdidaktik. Waxmann.

Behm, N. N., Glau, G. R., Holdstein, D. R., & White, E. M. (Eds.). (2013): The WPA Outcomes Statement: A decade later. Parlor Press.

Bräuer, G., & Girgensohn, K. (2012). Academic Literacy Development. In C. Thaiss, G. Bräuer, P. Carlino, L. Ganobcsik Williams, & A. Sinha (Eds.), Writing programs worldwide: Profiles of academic writing in many places (pp. 467-484). WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2012.0346

Brinkschulte, M. & Kreitz, D. (Eds.). (2017). Qualitative Methoden in der Schreibforschung. wbv.

Brinkschulte, M. (2019). Wissenschaftliche Methoden in empirischer Schreibforschung Einblick in Forschungspraktiken und didaktische Implikationen für eine wissenschaftsbasierte Methodenausbildung. In L. Hirsch-Weber, C. Loesch, & S. Scherer (Eds.), Forschung für die Schreibdidaktik: Voraussetzung oder institutioneller Irrweg? (pp. 61-76). Beltz Juventa.

Bromley, P. (2023). Locating the international writing center community. Journal für Schreibwissenschaft, 25, 10-20.

Bromley, P., Girgensohn, K., Northway, K., & Schonberg, E. (2021). An introduction to transatlantic writing center resources. Writing Center Journal, 38(3), 23-42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/27108273

Dreyfürst, S., & Sennewald, N. (Eds.). (2014). Schreiben: Grundlagentexte zur Theorie, Didaktik und Beratung. Barbara Budrich.

Ehlich, K., Steets, A., & Traunspurger, I. (2000). Schreiben für die Hochschule. Eine annotierte Bibliographie. Peter Lang.

Felten, Peter (2013). The SoTL reconsidered: An American perspective. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 12(4), 337-340.

Freise, F., & Hoffmann, N. (2025). Statements on the development status of German writing centers. JoSch–Journal für Schreibwissenschaft, 29, pp. 45-61. https://www.wbv.de/shop/Statements-on-the-Development-Status-of-German-Writing-Centers-JOS2501W005

Gesellschaft für Schreibdidaktik und Schreibforschung. (2018, August 31). Schreibforschung. www.schreibdidaktik.de/index.php/forschung

Gesellschaft für Schreibdidaktik und Schreibforschung. (2022). Positionspapier Schreibkompetenz im Studium. Verabschiedet am 29. September 2018 in Nürnberg. 2., korrigierte Ausgabe. [gefsus-Papiere; 1] Göttingen. https://www.gefsus.de/component/osdownloads/download/startseite-feld-positionspapier/positionspapier-2022-felder-download-startseite

Girgensohn, K. & Peters, N. (2012). “At university nothing speaks louder than research”: Plädoyer für Schreibzentrumsforschung. Zeitschrift Schreiben, 30(1), 1–11. https://zeitschrift-schreiben.ch/globalassets/zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/2012/girgensohn_schreibzentrumsforschung.pdf

Girgensohn, K. (2012, March 19). Worldwide writing against procrastination. How writing centers connect to make our work visible, support writers and have fun. Another Word. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/worldwide-writing-against-procrastination-how-writing-centers-connect-to-make-our-work-visible-support-writers-and-have-fun/

Gladstein, J. M., & Regaignon, D. R. (2012). Writing Program Administration at small liberal arts colleges. Parlor Press.

Harrington, S., Rhodes, K., Fischer, R., & Malenczyk, R. (Eds.). (2005). The outcomes book: Debate and consensus after the WPA Outcomes Statement. Utah State University Press.

Hoffmann, N. (2019). Schreibzentrumsforschung im deutschsprachigen Raum: Erhebungen zum aktuellen Stand und Desiderate. In A. Hirsch-Weber, C. Loesch, & S. Scherer (Eds.), Forschung für die Schreibdidaktik: Voraussetzung oder institutioneller Irrweg? (pp. 14-30). Beltz Juventa.

Hoffmann, N., & Freise, F. (2024). Rollen und Einflussmöglichkeiten von Schreibzentren an deutschen Hochschulen. Ergebnisse einer deutschlandweiten Umfrage zu Rahmenbedingungen und Aktivitäten von Schreibzentren. Hermes–Journal of Language and Communication in Business 65, 57-74. https://tidsskrift.dk/her/article/view/153162/195813

Hoffmann, N., & Freise, F. (2026). Zwischen Mangelbewältigung und Entwicklungs-Freiraum: Eine quantitative Bestandsaufnahme deutscher Schreibzentren [Manuscript in preparation].

Horner, B., NeCamp, S., & Donahue, C. (2011). Toward a multilingual composition scholarship: From English only to a translingual norm. College Composition & Communication, 63(2), 269-300. https://doi.org/10.58680/ccc201118392

Huber, L. (2014). Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Konzept, Geschichte, Formen, Entwicklungsaufgaben. In L. Huber, A. Pilniok, R. Sethe, B. Szczyrba, & M. Vogel (Eds.) Forschendes Lehren im eigenen Fach. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Beispielen (pp. 19-36). wbv.

Huemer, B., Doleschal, U., Wiederkehr, R., Brinkschulte, M., Girgensohn, K., Mertlitsch, C., & Dengscherz, S. (Eds.). (2021). Schreibwissenschaft – eine neue Disziplin: Diskursübergreifende Perspektiven. Böhlau Verlag.

Hughes, B., Liebetanz, F. & Voigt, A. (2023): Writing Fellows conversation. A journey from the US to Germany and back. JoSch–Journal für Schreibwissenschaft, 25, 51-60.

Hutchinson, G., & Perdigón, A. T. (2024). Decolonizing writing centers: An introduction. The Writing Center Journal, 42(1), vii–xiii. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27304232

Kiscaden, E., & Nash, L. A. (2015). Long Night Against Procrastination: A collaborative take on an international event. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 12(2), 8-10. https://www.praxisuwc.com/kiscaden-nash-122

Knorr, D. (Ed.). (2016). Akademisches Schreiben. Vom Qualitätspakt Lehre 1 geförderte Schreibprojekte. Universitätskolleg.

Knorr, D., Heine, C., & Engberg, J. (Eds.). (2014). Methods in writing process research. Peter Lang.

Kreitz, D., Röding, D., & Weisberg, J. (2019). Professionalisierungstendenzen der Hochschulschreibdidaktik Erkenntnisse aus dem Schreibdidaktiksurvey 2014. In L. Hirsch-Weber, C. Loesch & S. Scherer. Forschung für die Schreibdidaktik: Voraussetzung oder institutioneller Irrweg? (pp. 31-46). Beltz Juventa.

Kruse, O., Haacke, S., Doleschal, U., & Zwiauer, C. (2016). Editorial: Curriculare Aspekte von Schreib- und Forschungskompetenz. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung, 11, 9-21. https://doi.org/10.3217/zfhe-11-02/01

Lerche, E.-M., Netzer, K., & Limburg, A. (2017, November 9): Schreibzentrumsarbeit zwischen Berufung und Befristung? Unveröffentlichte Auswertung einer Umfrage mit SZ-Mitarbeitenden von 15 Schreibzentren im deutschsprachigen Raum. [Online forum post.] SchreibenAnHochschulen.

National Census on Writing. (2013). Four-year institution survey. Writing Centers: Are some of all of your writing center consultants undergraduate students? [Data set]. https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2013

National Census on Writing. (2017a). Four-year institution survey. Administrative positions. [Data set]. https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2017

National Census on Writing. (2017b). Four-year institution survey. Writing across the curriculum: What does the WAC program consist of? [Data set]. https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2017

O’Neill, P., Schendel, E., & Huot, B. (2002). Defining assessment as research: Moving from obligations to opportunities. WPA: Writing Program Administration, 26(1-2), 10-26. https://associationdatabase.co/archives/26n1-2/26n1-2oneill.pdf

Santa, T. (2009). Writing center tutor training: What is transferable across academic cultures? Zeitschrift Schreiben, 22(7), 1-6. https://zeitschrift-schreiben.ch/globalassets/zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/2009/santa_tutor_training.pdf

Schendel, E. & Macauley, W. J. (2012). Building writing center assessments that matter. Utah State University Press.

Schindler, K. (2016). Studium und Beruf. In M. Becker-Mrotzek,, J. Grabowski, & T. Steinhoff, (Eds.), Forschungshandbuch empirische Schreibdidaktik (pp. 109-124). Waxmann.

Scott, A. (2016, November 28). Re-centering writing center studies. What U.S.-based scholars can learn from their colleagues in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Zeitschrift Schreiben, 1-10. https://zeitschrift-schreiben.ch/globalassets/zeitschrift-schreiben.eu/2016/scott_writingcenterstudies.pdf

Scott, A. (2017a). The storying of writing centers outside the U.S.: Director narratives and the making of disciplinary identities in Germany and Austria. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 41(5-6), 10-17. https://doi.org/10.37514/WLN-J.2017.41.5.03

Scott, A. (2017b). “We would be well advised to agree on our own basic principles.” Schreiben as an agent of discipline-building in writing studies in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Liechtenstein. Journal of Academic Writing, 7(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v7i1.219

Stahlberg, N., Salden, P., & Barnat., M. (2019). Professionalisierung durch Forschung und Publikation? Scholarship of Academic Development in schreibdidaktischen Einrichtungen. In L. Hirsch-Weber, C. Loesch, & S. Scherer. Forschung für die Schreibdidaktik: Voraussetzung oder institutioneller Irrweg? (pp. 47-60). Beltz Juventa.

Venuti, L. (2017). The translator’s invisibility: A history of translation. Routledge.

Voigt, Anja (Ed.). (2018): Lehren und Lernen mit Writing Fellows. Beiträge zur Forschung, Evaluation und Adaption. wbv.

White, E. M., Elliot, N., & Peckham, I. (2015). Very like a whale: The assessment of writing programs. Utah State University Press.

Writing Centers Research Project. (2023). 2022-23 WCRP Results: Tutor/Consultant Info. [Data set] https://tableau.it.purdue.edu/t/public/views/WCRP2022-23/2022-23WCRPResults

Endnotes

- The chapter appears in the following German-language source: Hoffmann, N. (2019). Schreibzentrumsforschung im deutschsprachigen Raum: Erhebungen zum aktuellen Stand und Desiderate. In A. Hirsch-Weber, C. Loesch, & S. Scherer (Eds.), Forschung für die Schreibdidaktik: Voraussetzung oder institutioneller Irrweg? (14-30). Beltz Juventa. We thank Beltz Publishers for the opportunity to translate and publish this text in an online venue.↩

- The German context has more experience with using translation as a method. See, for example, Dreyfürst and Sennewald’s edited volume on key concepts in writing studies and didactics, which includes several translations from the English (Dreyfürst & Sennewald, 2014; see also Scott, 2017b).↩

- For example, the working group on the Production of Academic Texts with and without a Computer (which went by the German acronym Prowitec) and the working group Writing Didactics [Schreibdidaktik].↩

- For example, the Forum for Academic Writing [Forum wissenschaftliches Schreiben] in Switzerland in 2005; the Society for Academic Writing [Gesellschaft für wissenschaftliches Schreiben] in Austria in 2009; and the Society for Writing Didactics and Research [Gesellschaft für Schreibdidaktik und Schreibforschung] in Germany in 2013.↩

- For example, the Certification Program for Writing Consultants at the University of Education in Freiburg starting in 2003; the Certificate of Advanced Studies in Writing Consultations at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences starting in 2003; the one-time offering in 2011-2012 of a Higher Education Certificate in Writing Center Work and Literacy Management at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt Oder; the Higher Education Certificate in Literacy Management at the University of Education in Freiburg starting in 2012; and professional development workshops organized by the German Society for Writing Didactics and Research starting in 2016.↩

- For example, the Prowitec-Symposia starting in 1994; the Conferences of the Swiss Forum for Academic Academic starting 2006; the Peer Tutor in Writing Conferences starting in 2008; the annual conferences of the Austrian Society for Academic Writing; the conference Write Academia at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in 2013; the 2013 conference on Writing in the Disciplines at the University of Bielefeld; the [first biannual] conference of the European Writing Centers Association at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt Oder in 2014; the annual conference of the Writing Center of the University of Applied Sciences for Management and Communication in Vienna starting in 2014; the 2016 conference Advancing Academic Text Competence at the Ruhr University Bochum. [Since the publication of this article, there have been many conferences sponsored by individual writing centers, the country organizations, and EWCA.]↩

- For example, Zeitschrift Schreiben [Journal of Writing] starting in 2006 [final issue published in 2019]; the Journal der Schreibberatung [Journal of Writing Consultation], starting in 2010 [in 2020, renamed JoSch: Journal of Writing Studies to reflect the development of the field]; the Journal of Academic Writing starting in 2011; the series Theory and Praxis of Writing Studies [Theorie und Praxis der Schreibwissenschaft] starting in 2017 with wbv Press.↩

- Translators’ note: these three questions originally appear in the untranslated works’ abstract. We have repeated them here for clarity.↩

- Translators updated these links. For Germany: https://www.uni-bielefeld.de/einrichtungen/schreiblabor/vernetzung/; Knorr 2016; for Austria: https://www.gewiss.at/links.html; for Switzerland: https://www.forumschreiben.ch/vernetzung.↩

- It was assumed that additional WCs or initiatives for writing support exist that are not included on these lists and that not every website was kept up to date nor was the information included about the WCs exhaustive.↩

- Translators’ note: In 2023 Hoffman and Fridrun Freise conducted a systematic survey. Preliminary results were shared at the 2024 EWCA conference in Limerick, Ireland. A publication of some of their findings in English is available at Freise & Hoffmann (2025).↩

- In a survey of 49 writing scholars about their disciplinary orientation, the top three disciplines named were the scholarship of teaching and learning (21), linguistics (17), and foreign language acquisition (10) (see Brinkschulte, 2019). In a further study of 48 writing scholars, they listed the key publications for WCR as being Zeitschrift Schreiben with 24 mentions and Journal der Schreibberatung with 20 mentions, and the Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung [Journal for Higher Education Development] with 8 mentions (see Stahlberg et al., 2019).↩

- Translators’ note: In the study, writing center staff refers to professional staff in the German context, not to professional tutors or peer tutors in the U.S. context. For example, Hoffman and Freise (2024) found that in the German context 72% of WCs offered tutoring with peer tutors and 63% offered tutoring with professional staff.↩

- Translators’ note: In the original document, this term is directly translated as “individual consultations for non-native speakers [of German].” We’ve adjusted the terminology to align with the most up-to-date term in writing studies: speakers of German as an additional language.↩

- The German Society for Writing Didactics and Research defines writing studies as research that “investigates writing processes (writing research) and analyzes the teaching and support of writing processes (writing didactics research, applied writing studies).” (gefsus, 2018, n.p.). Translators’ note: This definition is no longer present in this form on the website as the field has evolved and grown.↩

- Translators’ note: The direct translation of the German term Schreibdidaktik is writing didactics. We chose to preserve the original phrase, since it is often used by writing professionals when they present on or translate their work at international conferences and other venues. Importantly, the term “writing pedagogy,” which is used in the U.S., evokes the German term “Pädagogik,” which refers only to K-12 teaching and learning. Writing didactics (and its cognates) are common terms in Germany, particularly for strategies to support those for whom German is an additional language. As shown in Figure 2, 17% of WCPs come with a background in foreign language pedagogy. Teaching and learning traditions outside the U.S., including Great Britain and Australia, often have deep seated traditions of didactics in the discipline (see Felten, 2013, p. 121).↩

- This is suggested by the results from the survey study by Kreitz, Röding & Weisberg (2019), where 47% of 90 writing consultants had completed training in writing pedagogy and 15% of respondents were student assistants who usually receive this training. The authors also noted that the percentage of professional staff with extra training in writing didactics decreases with the age of the respondent, which can be explained by the fact that such training has only been available in recent decades.↩

- To learn more about the effects and impacts of fixed-term contracts on WCSs, refer to Lerche et al. (2016). In it [a listserv post], the authors said, “The lack of a long-term perspective has a massive impact on motivation,” some of those surveyed decided, “to view work at the university as just a stopover and to look for alternatives early on or to build up a second source of income. This can have a problematic effect on teams if some are already internally ready to leave and are cutting back on their work at the expense of others, while others are still hoping for a long-term perspective and are accordingly committed to making up for the lack of commitment of their colleagues.”↩

- See also a survey study by Brinkschulte (2017) on a similar point. In her study, 49 writing researchers reported utilizing qualitative data collection and evaluation methods for various WCR purposes.↩

- After conducting the literature review, an anthology on writing fellows was published; see Voigt, 2018.↩