Christal Seahorn

Madeline Jones

The Peer Review, Volume 1, Issue 2, Fall 2017

Introduction

Act III, Scene i of William Shakespeare’s Henry V consists entirely of King Henry’s exhortation before the gates at Harfleur. The first line—“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more”—commands the English troops back to the battlefield. They have made progress, breached the French city, and their king urges them to re-engage and keep up the attack. Although a writing classroom is not a martial engagement, and applying a war metaphor to represent literacy development is itself problematic (Philip Eubanks, 2001), committing to a pedagogy that encourages students to challenge comfortable assumptions and participate in open discussions of contentious, sociopolitical topics can sometimes feel very much like going to battle. When faculty participate in embedded-consultant (EC) or fellows programs that incorporate Writing Center (WC) tutors directly into their courses, the consultants enter the trenches with them, ready to fight battles that they often had no hand in designing.

Faculty and students have a great deal of agency in contested classroom spaces: faculty set their curricula, and students often control topic selection and engagement level. For ECs, their supporting role requires them to enter and reenter the metaphorical breach even as they control neither the pedagogical objectives nor the content. Unlike one-on-one sessions in the WC, ECs have less autonomy with strategies and heuristics often dictated by the course design. This limited agency affects the kairotic dialogue and always influences the student-tutor relationship (Helen Raica-Klotz et al., 2014). The consistency of having an EC in the classroom has proven to be psychosocially and emotionally beneficial for first-year students (Jim Henry & Jennifer Sano-Franchini, 2011), but not enough attention has been given to the additional emotional labor this work demands from the EC. This article proposes that, as instructors who respond to the breakdown of our national political discourse by dedicating their classrooms to direct engagement with social justice work and inviting students into brave spaces, faculty-partners and WC directors must attend to how these decisions affect their ECs. Specifically, it highlights the dissonant forces at work in EC collaborations and the various relationships of influence that can support and challenge the EC’s professional space.

To illustrate these tensions, this article reconstructs a volatile six-month timeline during which a faculty-consultant team struggled to respond to the personal, political, and pedagogical exigencies that complicated their Composition I classroom environment. Having worked together for three years, the team had an established and trusted routine. The consultant attended each class session to work one-on-one and in small groups with students during in-class writing and workshopping, and the faculty-consultant team met after class regularly to discuss student progress and plan future interactions. Students were free to schedule appointments at the WC, as well. This formula functioned well in their relatively quiet first two years, but during the fall 2016 semester, personal and sociopolitical events upset their pattern and exposed weaknesses in their praxis.

Frustrated by the virulent anti-immigrant, racist, misogynistic rhetoric on display in the 2016 presidential election and wanting to confront what she saw as a critical breakdown of civil discourse, the instructor reworked an information literacy group project for her Composition I class. The five-week assignment originally required students to study the Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose (CRAAP) (2017) test for analyzing source reliability and to apply that heuristic to present a critical discussion of well-known fact-checking websites such as PolitiFact, FactCheck.org, the Pew Research Center. Prior to fall 2016, student productions were fairly straightforward, non-confrontational discussions of source credibility and uncovered bias. After watching the dissolution of public discourse in the presidential debates on mainstream news shows and in her social media spaces, the faculty member revised the group project [Appendix A] toward civic-engagement topics, grounded in the United States Constitution, and required that students incorporate social media and blog sources in addition to more conventionally-credible news and fact-checking sites. Rather than a comfortable analysis of one website, students would use their presentations to model public conversations that demonstrated dialectical reasoning and avoided logical fallacies. Although successful in many respects, these changes (and the election results) also led to unanticipated in-class conflicts that strained the resolve of both faculty and her embedded WC consultant.

This reflexive project arose out of the faculty-consultant team’s desire to process these experiences for how they could strengthen their collaborative approach ahead of the spring 2017 semester. Often, the end of a semester can feel exhausting, but this semester had felt like a fight for survival. Although they talked regularly during the focal timeline, the practical demands of administering the class did not allow for major scrutiny. While working together on another research project during winter break, the faculty-consultant team began to retrace their challenges from the previous fall. The EC had maintained a journal of her interactions; this served as the framework for their reflection and gave the project its chronological shape. Initially, they retraced consequential moments separately, (re)recording dates and reactions before putting their notes into conversation with each other. As they unpacked the emotional labor expended and strategized for the upcoming course, they realized that their trials held possible implications for training consultants and faculty participants in EC programs more broadly.

The discussion that follows represents the metacommunicative reflection between the instructor and consultant and situates it within available criticism on conflict and embedded-consultant programs. We organized the inquiry as a conversation between the consultant and the instructor because this delivery reinforces the pedagogical objectives of the group project at the center of the narrative and because the dialogic structure ensures that the consultant’s voice will not be elided or otherwise dominated by the professor’s. As instructors retool their pedagogical approaches to combat fake news and unchecked public bigotry, these decisions position ECs on the front lines and extend the reach of WCs as sites of social justice work.

Alarum

The timeline traces destabilizing episodes from summer 2016 to the start of spring 2017 during which external and personal events cause the faculty-EC team to reexamine their professional writing spaces as figurative lines of defense against abuses of information. The discussion takes place as a dialogic exchange that presents both instructor and consultant experiences but aims to rethink this progression of events from the consultant’s perspective. It calls on faculty-partners and WC administrators committed to cultivating brave(r) spaces to acknowledge the layers of vulnerability ECs often transcend to do their work and to develop effective support strategies.

July 19, 2016

Image and video credit: CNN.com Transcript

When Melania Trump plagiarized Michelle Obama [Fig. 1], it was the first time I saw the political landscape as a direct threat to my professional spaces. At the time, I didn’t recognize the impact it would have on the emotional labor that would be required in the coming semester. I was amazed and dismayed, and yet could not stop thinking how confusing it must be for students to have to learn a skill that we emphasize as so important, but then see it ignored in public.

This is how I felt throughout the entire election cycle, one shocking moment after the next. How were we supposed to get students to believe us when we teach about responsible attribution if public figures use blatant plagiarism without consequence?

At the time, a local high school called it an erosion of education, and I wondered how teachers were to inspire respect for these principles if our leaders had none. It jeopardized the integrity of what we do, like our core values were under attack.

July 28, 2016

Video: CNN Transcript

It was constantly destabilizing, and I desperately wanted to bring the election into class, but could not figure out how to do it. For me, the changemaker was Mr. Khan’s speech at the Democratic Convention [Fig. 2].

Oh yes, I gave Trump the finger after the speech—“Take that!” I was constantly appalled that Trump could get away with all that he was. I kept expecting someone to stand up and take control.

This speech directly influenced my approach to our first-year composition class. I was struggling to figure out how to (re)assert the fundamentals of our work as educators: the importance of preparation, respect for difference, elevation of evidenced-based reasoning. During the summer, I mostly fought this battle on Facebook, but I was always thinking about how to help students recognize these threats.

The idea that we have to be the enforcers while our country could be led by someone who doesn’t live up to these standards, questions our whole institution. I can’t deny that it was extremely emotional, and left me wondering, “What are we doing? What do we do with all of this?” I come from a lived experience based on norms and faith in institutions, held accountable and part of holding people accountable.

August 1, 2016

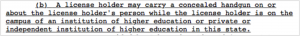

SB 11 permits students to carry guns onto Texas campuses

Yes! I agree so much. I wondered how we could hold students accountable. But also, how do we recover to a place that values reliable information and expertise? How can we regain a footing? Mr. Khan’s speech gave me the idea of adding the U.S. Constitution to our group project, as a primary text that would show there was supposed to be a standard for political engagements.Then, Senate Bill 11 [Fig. 3], authorizing people to carry concealed handguns on Texas campuses, goes into effect on August 1, on the 50th anniversary of the 1966 University of Texas tower shooting. This was a gut-wrenching twist of legislative fate in a summer that saw a UCLA student kill his professor over a grade dispute, the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, protests over the police shootings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, the murder of the five Dallas officers, and of course candidate Trump speculating that “those Second Amendment people” could do something about Hillary Clinton. We held a vigil for the Pulse shooting victims around the same time campus police held forums to discuss guns on our campus…as if we really had any ability to guarantee a safe environment.

At work, I announced, “Good morning! It’s Bring Your Gun to Work Day.” Everyone was on edge the first week. We went to the campus security workshops. Staff meetings were held to discuss procedures and to show us where the panic button is located.

You have a panic button in the Writing Center?

Yes, and Travis Webster [ our Director] reassured us we were not to place ourselves in danger; we could end a session if we felt threatened. I suggested a device to illuminate the table tucked away in the back by the conference room so reception could see all seating as tutors are typically out of eyesight at that table.

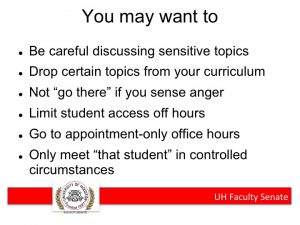

All this was before the fall semester, so you did not yet know that I changed the group project to tackle constitutional issues. To be honest, I didn’t think to tell you. Of course, the Second Amendment would be one of the possible topics, but I did not anticipate a problem. I should have communicated with you more directly during this time. The Faculty Senate (2016) at the University of Houston central campus had already held a series of Faculty Forums on the new law and published a slideshow suggesting that faculty “be careful discussing sensitive topics,” “drop certain topics from your curriculum,” and “not ‘go there’ if you sense anger” [Fig. 4]. I accepted Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens’ (2013) assertion that “authentic learning about social justice often requires the very qualities of risk, difficulty, and controversy that are defined as incompatible with safety” (2013, p. 139) and decided to be better about pursuing this “authentic” social justice work, even as I worried about campus carry.

After the Orlando shooting, Travis sent an email expressing his desire to keep us safe. In it, he reasserted his “inclusive and intersectional vision for writing support” (Rebecca Hallman & Travis Webster, 2017, p. 282). Did I feel safer? No. I still knew that the WC isn’t a designated gun-free zone, that students can bring guns to a session. What I really felt was appreciative, validated, and supported. I felt stronger because the letter was tangible proof that at the WC, on all levels, we acknowledged the precarious nature of our position, and we stood in solidarity.

I am struck by the fact that the sense of solidarity that Travis created works as long as you are in the WC. That fortification, even if only symbolic, does not instantly extend to our classroom, and you and I did not discuss how or whether we would address the campus carry policy in class. As a black, bisexual, faculty member, married to an ex-cop, I felt very destabilized by the summer’s events; both personally and professionally threatened by the new gun law and by the total disregard for facts and rational discussion that I saw on display in the election cycle. My way of reasserting power over the narrative was to invite politicized dissensus more directly into our class with an assignment that would, ideally, help students practice and value the use of evidence and rational, fact-driven disagreements. I wanted to push back, but I never considered th way in which these decisions meant you would have to do this pushing, as well.

I don’t think I was any more aware of the changes this would involve for me than you were. In fact, I think I reacted as a student: eager to learn something new. I had already accepted that embedded consulting is a steep learning curve. I also agreed with Megan L. Titus, Jenny L. Scudder, Josephine R. Boyle, and Alison Sudol (2014) who pointed out that “[Embedded Tutors] are trained to integrate what to learn with how to learn, guiding students to identify the content (the writing skill) with the process (the strategy).” I thought it would be simply a matter of adjusting to the new objectives you wanted the students to incorporate. And I was game.

Sure, but changing topics to ones explicitly located in discourses of unconstitutionality intentionally introduced narratives of conflict that students would have to navigate.

Of course, but that is what we do. What enticed me was modeling the strategy within an authentic context (Titus et al., 2014). We hadn’t done that before in this part of the class. I didn’t immediately realize that the shift would challenge me as much as the students. For me, it required understanding and negotiating a new level of non-directive/directive consulting fluidity. This area of communication between consultant and student is tricky. I accepted that the content was authentic (possibly even volatile) and thought it would help. I anticipated that the student’s passion for the topic would drive the interaction, and I wouldn’t need to be very directive.

This is a humbling point for me as the professor. When I make changes to my curriculum, my primary accountability is to the course objectives and whether assignment design guides student progress, but when I agreed to take part in the EC program, I also committed to creating space in my classroom for you to do your work. Inviting public displays of dissidence, even to model civic discourse, put you in the midst of this ongoing tension, too. I did not think of this while I planned the fall course. We do not want to advocate that faculty-consultant teams always make curricular changes together, this is neither pedagogically nor logistically practical, but faculty in EC and fellows programs should be aware that these changes affect the consultants, too, especially in a sociopolitical climate like this one where faculty are motivated to bring conscious-raising discussions into class.Even if we were both on board with elevating the level of purposeful antagonism in the classroom, that pedagogical fight takes a lot of energy and emotional labor to help students navigate these spaces of politicized dissensus. Doing this work does not leave much room for unexpected life events, and you and I both had personal developments just before the start of the semester that influenced our EC experiences and added to the emotional clutter we had to clear to do our work.

Yes, in August, my father died. I had mixed feelings about his death, but I was not examining them fully. I did wonder why I had not felt a deep sense of loss, and I wondered if I shouldn’t feel something even though we were estranged. I didn’t anticipate the return of these feelings in connection to current events, or the effect they would have on my work.

You told me about your father around the same time I told you about my cancer. What a start to the semester, huh? Two traumatic events for us but not enough time to process them before classes started. I had not told Travis about my diagnosis at this point, or many of my colleagues for that matter. Similar to what you said about your father, I just wanted to work and have as much normalcy as possible. I put you in a tough place, though, because you were the only WC person who knew about my illness. Did you experience any tension, being caught in this middle space?

August 22, 2016

First day of fall classes: “Unto the Breach”

You mentioned that you hadn’t told many people. I took note of that and considered it your decision to mention it when you felt like it. I knew I would not mention it, even if asked, out of respect for our friendship. It was unlikely that the knowledge of your cancer would complicate my work, as it is rare that conversation regarding a professor would occur in the WC or classroom. In our personal spaces, we were respectful of each other’s timing of revelations.

This back and forth negotiation you do as an EC situated between two clear authorities, me and your WC director—this is why I chose “the breach” metaphor for this text. Eubanks’ (2001) College Composition and Communications article, “Understanding Metaphors for Writing: In Defense of the Conduit Metaphor” lists a system of writing metaphors adopted by western societies: “Language Is Power, Writing Is Conversation, Ideas Are Products, Argument Is War, Truth Is Light, Understanding Is A Journey,” etc. (p. 94). Eubanks asserts that these conceptions govern our ontological and ethical rules for rhetorical dialogue—our commitment to fair reasoning, turn-taking, avoidance of falsehoods, for example. We use the frame of communicative warfare when we challenge students to perform these tactics, but there is also an emotional labor to entering this metaphorical battlefield.

September 22, 2016

Tension in the Writing Center

Sure. If we accept the WC and the classroom as contested spaces, when we cross the breach, as you call it, we often battle more than merely the pedagogical objectives. It takes emotional stamina to keep tackling these issues from different angles.

I have an advantage as an instructor: I design the assignments that encourage dissonance in our first-year Comp class. Consultants never know what kinds of topics students will need help with in the WC and may not have the repeated contact time that we have in the classroom. Surely, your WC sessions do not always go smoothly.

No, not always. In fact, the day before you had to miss class for your surgery, I had a difficult session in the Center with a student. He was working on a political topic and was clearly invested in his position. The problem was a common one: he wasn’t considering counterarguments. We reshaped the thesis sentence, but this was disappointing for him, and I haven’t seen that student since.

That you never saw him again is one of the ways that embedded consulting demands a readiness that is notably different from WC consulting. It is another reason the “breach” metaphor suits this analysis, and it is not just our experience. Look at how Crystal Brinson characterizes the challenges of working as an EC:

You have to learn to be okay with seeing the students more than once, whether you like that person or not. When I worked in the Center it was easy to help a student, complete a task, and leave the Center. Working in the classroom is different because when you have a “bad session” or become frustrated, you have to learn to take a step back and then re-approach the situation another day. It is critical that you do not offend a student and walk away, because that student will be there the next week. You have to be patient. -Raica-Klotz, et al., 2014, p. 24

Brinson captures a human truth that faculty know all too well, that we cannot “like” every student and that sessions or classes are not always successful. As she draws the distinction, she adopts the language of repeated engagement: “more than once,” “complete…and leave,” “take a step back and then re-approach.” Brinson’s imagery indicates the EC’s routine existence of being at the breach and trying varied tactics again and again with the same student or on the same course concept.

Effective EC programs locate consultants in a space that is more intimately connected with the class proceeding, yet the ongoing nature of this engagement requires a brave(r) resolve from the consultant who must navigate, and at times compete with, relationships of accountability.

Of course, that accountability is not limited to EC-student interaction. At times, it reflects the power structure of departments and their interactions. When Dr. D. offered to sub for you when you had to have surgery in September, Travis wanted to know if I would be ok with the switch or if I wanted more support from the WC.

We should explain that Dr. D. is my program director and the founder and former WC director. So, she used to be your boss and started our EC program. For my part, her volunteering to take the class was ideal because I did not have to tell anyone new about my treatment, and it would be a good chance to show how well her idea for our faculty-consultant collaboration had worked.

I was nervous. I was becoming acutely aware of the pervasiveness of workplace politics and how my life was being inundated with issues that I have previously been too low on the totem pole to be personally affected by(or so I thought) and that I deliberately tried to avoid at work. We were both professional and friendly. I introduced Dr. D. and said she would be leading the class since the WC recognizes the classroom as the professor’s domain. After she announced a workshop day, she asked how we usually do it. I suggested our normal practice of dividing the students into two groups that we would circulate through and answer questions as they arose. Later, we had a friendly conversation on our way back to the offices.

It is interesting that you introduced her and then stepped back to let her lead the class. Issues of power and authority are always present in class-based consultant collaborations (Steven Corbett, 2015). You and I have worked together long enough to feel confident in our roles now, but a substitute could have been a situation where you felt your place was challenged, or you could have been expected to over-perform and “teach” the class. It sounds like there wasn’t any role confusion.

September 23, 2016

Negotiating authority with a substitute

When I did my student teaching, I became familiar with the power struggle between mentor-teacher and student-teacher, and substitute-teacher and studentteacher. So, I was familiar with that dynamic and aware that it can manifest in both unpleasant and productive ways. In addition, I had been trained in the WC that consultants defer to the instructions of the professor, usually represented by the assignment sheet. I was accustomed to thinking of the classroom as the professor’s “domain.” Lastly, in the past, Dr. D. was my boss; she was also the director I trained under. I have always recognized her as an authority figure. It felt natural to do so this time. This experience reflects the often unforeseen layers of complexity that slowly build up and affect my role as an effective EC and as an ambassador of the WC.

October 5, 2016

Feminist teacher reading defines “civil discourse”

While the surgery and the transfer of classroom control disrupted my semester and forced you to navigate unexpected power dynamics, your presence in class while I was out maintained continuity for the students. Because you were so familiar with our processes and cultivated a healthy professional relationship with the substitute, I was able to heal, and students did not have to miss any deadlines. This is a valuable contribution of working EC relationships.When I returned to the classroom, I was still reworking the group assignment into October. In prior years, students performed a skit to simulate an academic conversation about source credibility, using the CRAAP Test (2017). I wanted to keep the dialogic presentation, but I wanted a more hard-hitting project. I added the Constitution after Khizr Khan’s DNC speech, but I struggled to weave this text into the project as more than a source for topic invention.That was when my monthly reading group for feminist pedagogies gave me the idea that would become the cornerstone of the project. Like many teachers, the members of our reading group were feeling threatened by the anti-intellectualism and false-equivalencies that pervaded election coverage. Our October theme was on teaching “Civil Discourse.” We read “A Plea for Civil Discourse” in which Andrea Leskes (2013) identified, “a visceral and gripping fear that the current breakdown in public discourse is eating away at the very core of US democracy, thereby also undermining the climate a great academic community needs to thrive.”

Well, with a month to go before Election Day 2016, and a climate change-denying candidate who won his nomination with verbal attacks and fear-mongering; professional and citizen journalists incapable of or unwilling to challenge false equivalences; and the public all too willing to fall for clickbait and fake news, I’d say Leskes’ (2013) “visceral and gripping fear” was justified.

Exactly. It was during this feminist pedagogy discussion that I decided to have our Composition I groups model civil discourse, and I added Leskes’ (2013) principles to the assignment to help students understand the norms of these kinds of exchanges:

- undertake a serious exchange of views

- focus on the issues rather than on the individual(s) espousing them

- defend their interpretations using verified information

- thoughtfully listen to what others say

- seek the sources of disagreements and points of common purpose

- embody open-mindedness and a willingness change their minds

- assume they will need to compromise and are willing to do so

- treat the ideas of others with respect

- avoid violence (physical, emotional, and verbal).

I shared this new plan with you after class that Friday, October 7, but this was only one week before the group project began.

October 10, 2016

Framing the Battle: The Constitution Naturalized Citizen Class Visit

You are always making changes to the class, so I was not surprised at these last-minute changes. I thought the shift made the assignment more relevant, integral to the students’ world. At this point, I don’t think we were thinking that there would be a “debate” element that would escalate.

Of course, this same Friday, the Access Hollywood video dropped and made an emphasis on civil discourse feel even more urgent [Fig. 5].

I was furious, positive this would cost him the election. I was shocked that the campaign passed it off as “locker room talk”. None of our students mentioned it to me. Most of them were too busy with their assignments to be concerned about the political scene.

Video:CNN Transcript

I was surprised that none of the students brought it up, too. There were a few very politically-engaged students in this class, but we had not begun the group project yet, so there was not an intentional space that made room for these conversations. As disgusting as the comments were, I thought the Access Hollywood tape would solidify what I wanted students to gain from the literacy project collaborations: that the standards for a president are, in part, connected to language use and that how we talk and use information has consequences. Like you, I thought now the country will surely reject him…and we can all move on.

When you had the students make a pocket Constitution in class, I remember a student remarked about how neat the pocket size was. You worried that students would miss the point of the assignment. You wanted them to understand how important the Constitution is, but my reading was that everyone seemed to understand and appreciate the physical activity. I don’t think anyone anticipated problems. They were a friendly group and seemed to trust each other.

It is interesting that you remember a sense of trust among the students. Even though they had not picked groups yet, there was a positive energy in the class. I wonder if the students felt a sense of gaining more control over the national landscape.

Yes, a way to put it into perspective as relative to their lives. The project provided an arena where their views and observations were significant and listened to. Because the scripts would be pre-rehearsed, they could role-play without being fully vulnerable, and using the Constitution as a primary source grounded them in the history.

I was nervous about bringing Juan José to class, but in the face of all the xenophobic rhetoric in the election, I wanted students to put a face to U.S. immigration. As a recently naturalized citizen and a Latino from Ecuador, Juan José challenged assumptions about why immigrants come to the U.S., and he offered a unique perspective on the U.S. Constitution.

October 14, 2016

Naturalized citizen class visit

Framing the Battle: The Constitution

Several students mentioned that they enjoyed his visit. Some spoke with him after class. Several were surprised that Ecuador had revised their constitution twenty times. It worked out that your inspiration for bringing the Constitution into the assignment was an immigrant, Khizr Khan, and then the students were able to connect immigration directly with a visiting speaker, but I’m not sure if they were viewing immigration as a global, political issue or as a personal issue. Some of the students did have experiences that they shared.

How valuable is it for you to be in class on a speaker day? There wasn’t time in class this day to work with students on their writing, as you normally do. Did you think about staying in the WC to take a one-to-one appointment instead of sitting in on the class visit?

No. It was important for me to understand what the students would find interesting about his presentation in case it influenced how they interpreted the Constitution, especially since we had immigrants and international students in class. This exchange of information facilitates my connection with students when they are grappling with how to express themselves using a particular writing strategy. It avoids long explanations that slow or derail the transition to in-class writing. We had Juan José’s visit as a common experience to draw from as the groups designed their discourses.

After this initial foundation-forming with reading the Constitution and Juan José’s visit, we committed lots of time to student-driven group work for the weeks leading up to final presentations. You and I were available for support, but mostly groups set the pace of progress.

You gave a few lectures during this time: one on logical fallacies and another on civil discourse. I remember you stressed the difference between dialectic and debate. There had already been three presidential debates, and all the news talked about after each was who “won.” You talked about civil discourse as the exchange of ideas, new viewpoints, and a larger understanding of an issue, then showed examples using gun control discussions from Fox News and Bill Maher.

Groups had the option of accepting our help. Looking back, I recall that the one group that ended up changing their topic at the last minute had struggled throughout this time, working but not making much progress.

October 17-November 4, 2016

Marching on:Weeks 2-4

My journal notes show that you and I both tried to check in with them each class. Because the topics were so political, I became increasingly aware as I circulated through the class of what I could and couldn’t say. The students were operating on two levels: expressing their ideological opinions and learning how to apply the CRAAP Test (2017) to evaluate their support. While I was experienced in remaining neutral and not interjecting my personal views, my job was to help students recognize when a source was not credible or relevant. I became keenly aware that every day I had to return to the classroom and work with the students as their knowledge and ideas evolved. I needed to be very diplomatic, especially when they incorporated unreliable sources.

But unreliable sources were an intentional part of this project. Students had to bring in social media—memes, posts, comments, etc.—as part of their discourses. You would have faced this resistance and confusion even if these students had made WC appointments. Did the embedded experience require more neutrality or diplomacy?

November 7, 2016

The Theater of War: Presentation Week

In the WC, I disagree or point out that something does not support the writer’s point, and the writer usually wants to know why or debate with me. They know that in the end it is their decision. In the classroom, the student takes my comment literally. They feel I speak for you. They made an academic mistake, and some take it personally. This may be due to previous writing experiences or how the student interprets my role (Corbett, 2015, p. 92).

My interactions during and after class with the students were filled with questions about the presentations and the annotated bibliography. They wanted to know about deadlines, how many copies of the documents to submit, etc. It appeared to be a very efficient and detailed follow up on their parts, sort of putting their ducks in a row. One student stayed after class to talk about family recipes for Thanksgiving.

These are elements of class engagement that you do not often see when you consult in the WC. How does this aspect of your work as an EC affect how you navigate and process the students’ development?

They help me get to know the students and break the ice. One student became quite friendly. Another recognized what information she could get from me without having to wait for you. One came to the WC more than once. He joked with me more than as just a person. I think these interactions help them see me in a friendly light. They don’t have to commit to an appointment with me. They can just know me and talk with me.I honestly thought everyone was getting it. I wrote in my journal, “Christal is more pleased with how this project is shaping up compared to how it worked the first time. Still open to tweaks.”

I was excited about how the group projects were developing, and I had figured the timing perfectly: presentations would take place right after the election. It would be a triumph of civil discourse during the same week that the nation rejected the crudeness and disrespect of Trump’s campaign and elected our first woman president. Experience, preparation, and decency would prevail; the world would stabilize, and we could go about the business of teaching students to disagree responsibly and to trust that credible facts matter. I proudly wore my “I voted” sticker to class on Tuesday [Fig. 6.].

I woke up for class on Wednesday after the election furious, frightened. I began targeting old, white, good ol’ boys in the supermarket. Just a little bit rude, extra slow in the checkout lane, blocking the aisle so they had to wait until I’d made my selection. Childish, but I immediately became an angry, white woman. It forced me to think about my father, too. My father’s death impacted how I saw the political situation and the oppression of women and especially girls. The students’ success on the project had made me hopeful.

November 8, 2016

Election Day

I did not experience the same anger, but I was deeply disillusioned after Trump’s win. The night of the election, Ali Michael (2016), Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania wrote a piece for Huffington Post in which she asked the question I was grappling with, “What Do We Tell the Children?” Michael’s first suggestion to teachers seemed laughable. She wrote:

Tell them, first, that we will protect them. Tell them that we have democratic processes in the U.S. that make it impossible for one mean person to do too much damage. Tell them that we will protect those democratic processes–and we will use them–so that Trump is unable to act on many of the false promises he made during his campaign.

“We will protect them”? Michael must not work at a Hispanic-Serving Institution with 15% international students. We will protect them. Ha! We proved on November 8 that we could not protect them. I didn’t feel safe; I had not felt safe since the possibility of a Trump presidency became a real thing. I could not muster the nerve to give my students a false guarantee of their safety. I did not know what to tell them. Going into the first day of the civil discourse presentations, I felt completely destabilized. I wanted to tell the students something that would restore legitimacy to the work we had had them do on this project.

Only one group volunteered to present the first day. They created a talk show, “Justice or Murder,” to discuss the Eighth Amendment and the death penalty [Fig. 7].

November 9, 2016

Group Presentations Day 1

Included with permission.Transcript

This group was impressive. They met the standards of civil discourse. Their skit was an exchange of ideas. They created characters that presented a diversity of perspectives: a doctor, a clergyman, and a politician. They smoothly incorporated the sources and the CRAAP (2017) test. The audio was hard to hear at times, but the script demonstrates the group’s hard work and success at incorporating the assignment objectives.

It was heartening to see this group’s presentation first after the election results. One danger of this project is that conventions of “civility” are so often defined by the privileged and can dilute individuality and diversity. John Trimbur (1989) addressed this anxiety that collaboration breeds conformity, arguing that “it is through the social interaction of shared activity that individuals realize their own power to take control of their situation by collaborating with others” (p. 604). By giving the students control over their characters and how they performed discourses of power, this assignment was not intended to erase the asymmetries and inequality or create a dialogic utopia where all the nation’s problems were solved but to make room for a multiplicity of voices, each student taking on a purposeful role. The scriptedness of the dialogs made the exercise somewhat artificial, but the act of creating and verbalizing these intersections was valuable.

This group definitely thought it was valuable. You said they were the first to volunteer their project for this article. It was valuable for me to participate as an audience member, too; I ask questions in the same way I would if I were working on a presentation with a student at the WC, but I also get to continue asking questions after class as an interested participant. Once again, I’m building ongoing relationships, and I have a genuine interest in the progress of the students. In the WC, it is rare that a student returns to tell you the outcome of their work. Seeing the students present lets me see their growth. Juxtaposed right after Trump’s victory, the success of these presentations felt a little hollow.

Because I allowed students to volunteer for presentation times, the second day was more tightly scheduled than the first. We had six groups to fit into the 50-minute class. The time was only doable if we limited Q&A to two questions.

Yes, and I was away at a conference, so I couldn’t help by keeping track of time or making sure the next group was ready.

November 11, 2016

Group Presentations: Day 2

Right, so I had allowed this time constraint, assuming that everything would go as smoothly as the first day. Then, one group announced that the night before they had changed their topic, switching from the Fourth Amendment, illegal search and seizure, to the Second Amendment and the right to bear arms. Originally, they had wanted to argue that the NSA was overreaching by illegally seizing online information on U.S. citizens, but after more research, they found that laws had been changed to prevent the kinds of violations they thought were happening. Now, we had been working on this project for four weeks at this point. Retracing their discovery process would actually have made for an excellent presentation to illustrate information literacy with civil discourse. I wonder if our working more closely with this group might have saved them this last-minute shift.

Yes, I tried to work with them regularly, checking in with them as I made my rounds with the groups on workdays. They were polite, but my offers were met with “We’re good,” “We’ve got it,” and shakes of the head. Once we moved into workdays and groups were no longer brainstorming and fact checking, I’d give a nod; they’d return a nod, and I’d move on. They gave the impression they were on top of it, talking and laughing while planning. I occasionally checked to see what was coming up on the computer screens; it appeared to be topic related.

Because we set up your EC relationship to be fluid, students have you as an optional source of assistance, but they are not required to work with you. It is pretty consistent that there is at least one student or group who responds a bit coldly to your offers to help, yes?

Yes, some prefer to do their own work as a natural process. Others feel they need to network with the professor. Consulting in the WC does not give me the opportunity to speculate on why a student does not come back. In class, I have ongoing relationships with the students. I can see if they switch to asking you the majority of their questions or if they work alone. In the WC, they just don’t show back up on my schedule.

I wish we had forced more directive guidance with this group. The shift to the Second Amendment alarmed me, but only because it occurred so late in the process. I was too busy trying to get presentations going to consider that a new topic, hastily prepared, might create a conflict. Looking back, I can see how tensions escalated.Just before the Second Amendment presentation, we had a strong performance on Illegal Search and Seizure. This was a diverse group with students who had each previously written about how their identities affected their academic experiences. They included an exchange student from the Philippines, a student who immigrated from Kuwait, a Muslim student who had written his first essay about learning to recite the Qur’an in Classical Arabic, and another student who wrote a literacy narrative about being caught between her white and Latinx heritages. The exchange student had expressed to her group mates that she was nervous about speaking in front of the class on this topic because English was not her native language, and she was not an expert on the U.S. Constitution.

Yes, I remember this group stayed after class regularly to work on the project. She was very concerned about her inability to speak fluently. When we spoke in class or at the WC, she always wanted me to check her grammar because she was afraid she wasn’t making her point clearly enough for the audience to follow.

Audio Included with permission Transcript

When they created their dialog, they made her host of their talk show; that way, if she had questions about the topic or the Constitution, she would not have to be an expert and asking questions would be a natural part of her role. They even called it “Grace’s Talk Show” [Fig 8].

When I listened to the audio later, I thought this was a significant act of collaboration by the group. They could have considered this an unsolvable disadvantage and told her that she would just have to do the best she could. I think that would have totally deflated her. However, this decision was a great relief to her. She was engaged with the project again, confident. She started to smile and offer suggestions. When she stumbled during the talk show, she just kept going; she didn’t stop to apologize or get embarrassed.

Two significant moments happened during their presentation. First, the group intentionally allowed dialog to devolve into a shouting match. They closed with a summative statement about how civil discourse can deteriorate and that their goal was to emphasize that adversarial conversations do not have to be chaotic.

This group clearly understood the concept of civil discourse. They showed a depth of understanding about how the media can slant information by cherry-picking parts of an exchange between candidates to influence “average citizens,” as the group called them. This was well done. We definitely had students who were “getting it.”

Audio included with permissionTranscript

Certainly. Then during Q&A, an audience-student mentioned a moment in the presentation when the exchange student made the comment that her home country, the Philippines, had adopted the U.S. Constitution. The audience-student said that she was surprised to learn this information. She acknowledged that she never knew how much other countries relied on our Constitution, to which the exchange student responded, “Yes, we adopted the Constitution here, the Bill of Rights, but the Second Amendment, no, the..the..about the guns? No. But we appreciate the Constitution here.” This full audio is linked below. The Second Amendment comments occur during the Q&A, about timestamp 06:50. It is a bit hard to hear the question, but the answer is clear. By pure random order, the Second Amendment group who had changed their topic at the last minute presented directly after this one. They performed their “Liberty and Justice for All” talk show, with a host and two guests, “a member of the lobbyist political group, Guns Second, Safety First” and a “famous member of the NRA with years of gun knowledge and an opponent of gun reform” [Fig. 9]. As could be expected from such a last-minute change, their dialog did not develop the nuances of the gun control discussion. The exchange was a volley of statistics that finished with a claim to “let America decide.” During the Q&A, about timestamp 05:18, the student who had played the NRA member responded combatively to a question. The students had been allowed to violate civil discourse practices during the skit to illustrate behaviors they see on display in public discussions, like being overly argumentative or deploying logical fallacies; however, they were supposed to shift out of their character roles for the Q&A to demonstrate their understanding of Leskes’ (2013) principles: thoughtfully listening to others, seeking points of common purpose, embodying open-mindedness and a willingness to compromise, avoid violence, etc. For the second question after the gun discussion, a student asked whether the presenters thought a compromise could ever happen between gun-rights and gun-control activists. The NRA student’s response is aggressive, as you may be able to detect from the audio. He said, “Well, someone give your idea, and I’ll tell you why we won’t do that.”

After listening to the tape—Yeah, he was aggressive; eager for a chance to slap someone down. He was cocky, smug. He’s young. He didn’t attempt to corner or challenge anyone in particular, but he did work to define and control the exchange.

Very true. I jumped in because I worried the audience would feel attacked and tried to clarify that the Q&A was not a space for shooting down individual ideas (a poorly selected metaphor in retrospect). The student who played the talk show host asserted his belief that “no one should take away our guns” but that he believed there “does need to be protection.” Then the NRA student said, “This is just something I’m going to say real quick is that my personal problem with putting in any legislation is that only law-abiding citizens will listen to that….” He presented more statistics on the number of inmates who acquire guns illegally, then said, “Don’t try to fool yourself into thinking you can lessen who can have a gun just because you took it away from people who could legally have it.” At this point, I jumped in again. Two groups still needed to present, and I did not have the energy to mediate effectively.

It sounds like no one engaged with him on his level. He admitted that this disappointed him. Perhaps that is why he hung around after class to continue the conversation with you. You are familiar with the research of Arao & Clemens (2013) who write that brave spaces are inherently challenging because they open dialogs of power relations and social justice. I suppose there were “signs” you could point to as clues in hindsight. But clearly there was no foreshadowing in the weeks prior. You may have been particularly sensitive to these power dynamics so soon after the election.

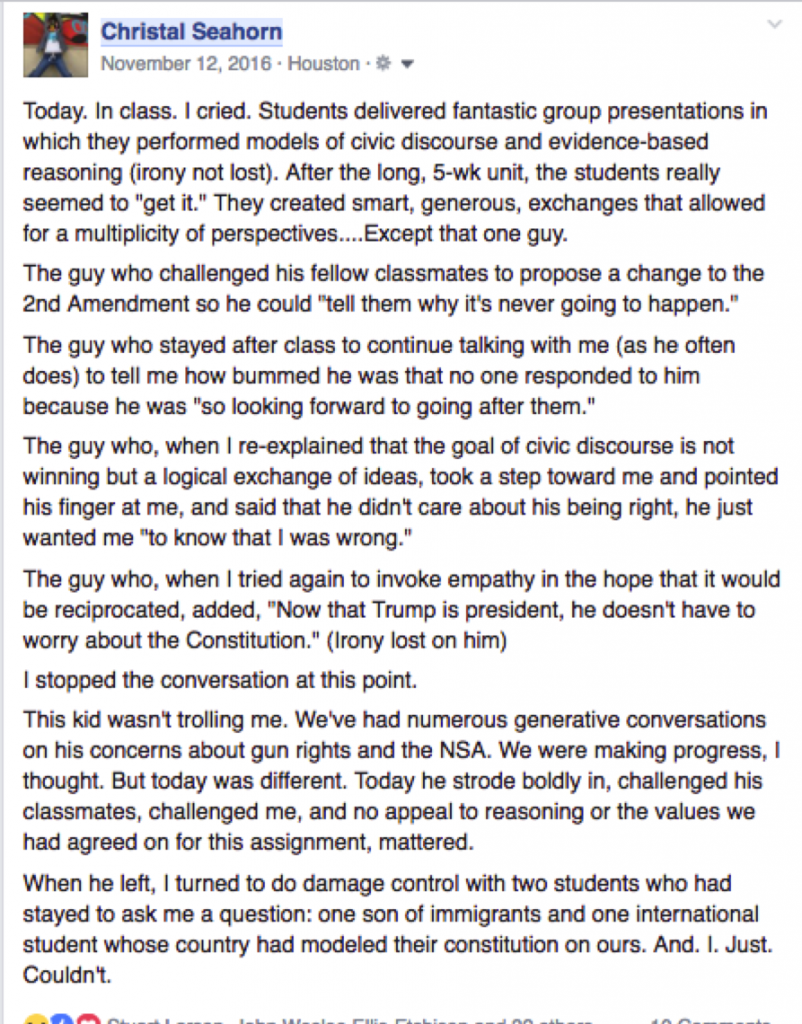

Completely. I remember that, as the group went back to their seat, the NRA student emphatically placed his cowboy hat on his head. He had worn jeans, boots, and the hat as part of his persona for the skit. Through my post-election filter, these were emblems of privilege and excess. I was frustrated that the conservative, white male was the one who seemed to have missed the point of the project and was now asserting dominance. I thought the incident was done…until he decided to stay after class to continue the Second Amendment discussion with me. The resultant exchange was so powerful for me that I retreated to a private group of Facebook friends to share my frustration and disillusionment [Fig. 10].

November 12, 2016

(just after midnight)

Retreat to Facebook

When I read this, I was shocked about what happened. I couldn’t believe that a student had done this. I also felt concerned for the two students in the room. I seriously questioned if he was just letting off steam and how likely something of this nature could happen again. At first, I thought we’d call campus security, a knee-jerk reaction. Then I realized how naive this is because the student had not threatened you with bodily harm, but he had threatened you by invading your personal space and disregarding classroom protocol. But I was stumped as to what to do to preempt this type of incident and reassert a “safe space.”

Another Facebook colleague also asked if I wanted to contact campus police. I had never considered it. I did not feel physically threatened. It just felt like I had failed them—all of them. There is a moment in Andrea Riley-Mukavetz’s (2016) audio essay “On Working from or with Anger” when she describes the feelings that cultural rhetorics can evoke:

You’re in between tears and throwing things. You desire to be that teacher who can spontaneously change her lesson plans and address these issues with her students in meaningful ways. But you can’t. You’ve always been a mess. You’ve always felt too deeply. Already, you tread lightly in your classroom. You make sure to not take up too much space. You are afraid of how your students perceive you.

I remember wanting to be so much more in that post-class discussion. This student’s aggression was not physically imposing. He and I had debated politics on other occasions, but this time felt different. “In between tears and throwing things,” I was acutely aware of my intersectionality as woman, as black, as gay, as pre-tenure, and I wondered how those identities factored into the exchange and how much space they stole from my authority as professor. Even as I tried to engage with and continue to follow the civic discourse standards we had covered in class, I was mindful of the two students who were still in the room and how they would perceive the incident. I do not know if he was performing for them, but I certainly was.

We talk about being aware of the politics in the WC. Travis made it a focus of staff meetings with a speaker series. Being aware of the students in the class is being in the moment. You identified with their otherness. According to Anne Ellen Geller, Michele Eodice, Frankie Condon, Meg Carroll, and Elizabeth H. Boquet (2006) we cannot “completely escape resembling and reproducing much of what students of color experience outside [writing center] spaces” (p. 92). In identifying, you tapped into the feeling of powerlessness that in our society is, unfortunately, inherently there. Continuing to model civic discourse or shutting down the conversation are two ways to avoid reproducing the experiences of powerlessness the students of color watching the conversation (and you) likely experienced.

This is it. We failed as a country to reject brashness and bullying, and this exchange was a microcosm of larger sociocultural dynamics. Admittedly, I felt somewhat foolish having a power struggle with a student, but I thought the investment would be worthwhile if he came to understand the value of mutual respect for difference which the project was supposed to teach. Goes to show my ego. His group mates probably tried this for four weeks.After he left, I realized that his behavior was that of someone under no obligation to approach the discussion with a genuine interest in seeing outside of his own perspective. At that time, it felt like the only students who had actually learned these lessons for their lives outside the classroom were ones, like the two students who remained in the room, who had to practice sensitivity, empathy, and patience as part of surviving as a minority. I remember adding on my Facebook post that “My work just got a lot harder.”

November 14, 2016

Reconciliation: The First day back

It was a few days before you and I discussed this incident. I did notice that the student was quiet in class and didn’t hang around afterwards like he usually did. None of the students said anything to me. Travis did ask about it. He had seen your post and wanted to know what the atmosphere was like in the class, if we were ok, or if another presence would be helpful. I think he was more concerned about me than you. He was unsure if I had encountered an incident of this nature before. (I don’t think he knows I was a head supervisor of a minimal security facility, ages 10-17, male, female, all races.) I told him you were moving along with the next assignment, and that I had not experienced any change in how the students were relating to me.

That demonstrates how this kind of conflict alters your professional spaces. Travis and I are Facebook friends. He is in the private group I created after the election for times when I needed to escape my main page (I have a lot of Republicans on my feed). If he and I did not have this relationship, your WC administrator may not have known to offer you support.

Conflicts like this must be shared. In the WC, when we have “problem” sessions or students, these instances are shared at staff meetings and end-of-session reports. Usually, these students return and are fine. The same consultant often continues to work with them. I have. We expect emotion, especially when students feel strongly about their topics. We have never had a student get in a consultant’s face, but now this is the age of campus gun carry. The WC, classrooms, professors’ offices–none of these are gun-free zones.

We don’t have systems in place yet to communicate combative experiences within the EC program. The WC director is physically farther from the interaction than he is in the Center and could be out of the loop completely without regular communication. I also wonder how much it presents a conflict for me to share my emotional responses with you, whether it compromises your ability to approach all students fairly and objectively.

I did wonder what I would have done if I’d been in the classroom and what I could offer students. The political atmosphere is making identity a priority in my life. It is important to me that you and Travis see me as a capable professional. My job as both an EC and a WC consultant puts me into constantly shifting, often competing contact zones (Raica-Klotz, et al., 2014, p. 23), but you and my WC director are not responsible for some paternalistic kind of protection. As I become more aware of the nuances of perceived identity, I become more adept at integrating and responding to spontaneous moments.

What do you mean by the “nuances of perceived identity?”

Well, I am thinking more about how students perceive me. I identify as a minority: as a woman of a lower socioeconomic status. I do not see myself as representing the “privilege,” yet because I am white, students may not see me as different from those who are privileged. On the day you told me about the incident with the gun-rights student, I also went to an LGBTQ ally training. We did an exercise where you collect beads from different stations around the room based on how you answer questions. After three stations, I noticed I was collecting beads like crazy. I looked around, and others only had two or three beads. I thought maybe I had misread the instructions, so I started over. Then it dawned on me: I was one of only two people in the room who was not a recognizable minority. The only person more privileged than me was a white male. I was getting all of these beads because I was white, and only because I was white. This realization was humiliating. The fact that my “truth” was not the “truth” that others identified me by was disconcerting. In the classroom, I started to wonder how they saw me, to question my credibility. I wondered if my “whiteness” made me unapproachable, and if I had been naive not to have thought about it before.

You had understood these shifting contact zones on a professional level, but this sounds like you were coming to an uncomfortable personal awareness of the multidimensionality of oppression and discrimination. You describe what social justice activists call getting woke.

Well, being woke made me an angry person to be around. Still, I thought that I had compartmentalized my feelings and was in control, performing professionally; however, the underlying tensions eventually surfaced. I went off at a WC staff meeting when someone made an off-hand remark that we could “just have the receptionist do it” (some extra work that no one else wanted to do). More aware of structural inequalities, I was livid. I had taken more time to listen and empathize with students in the classroom and the WC, and I was angry that others would be so dismissive. It’s a good thing we had Christmas break at this time because I was burnt out. The constant emotional labor on top of the co-processing of intense political, personal, and professional events had taken a toll on me.

December 2016

Winter Break

The anger you recall is certainly an ongoing part of this coming to awareness. It added to the emotional drain. This winter break was important for both of us and gave us the idea for this article. We finally had time to recover and process the semester. It was a somewhat stressing time for me because I had treatment every day, but you and I worked more closely together than we had in previous breaks. We were collaborating on research and emailing back and forth.

I was very hesitant about writing this article. I hadn’t been present for the incident, and I’d never written an academic article. I questioned what I could offer students. How could I contribute to the conversation? I did not determine class design. My role was to assist.

Your uncertainty makes sense. The conversation with the NRA student in the group project, for instance, may have gone differently with another authority presence in the room. Even so, I anticipate an event like this will happen again, and our social identities are always already political. Now that I committed to addressing institutional power dynamics more directly in class, you will have to address those issues as well. It is one thing for me to encourage a braver discourse in service to the course content, but my choices define that space for you and, by extension, the WC.

While you were processing that, I was at home distanced from work, reflecting on the political state of the world, and how it impacts the WC and the classroom, and how I negotiate my identity. I remember last summer when I visited Marble Falls to help when my father entered the hospital for the last time. I saw my mother, a college-educated woman, drugged and “quieted” (silenced—my word) by my father because he was “entitled to be unchallenged in his home.” While I protested, my power was limited because once my visit was over, and I was driving back to Houston, my sister was driving to the pharmacy to refill the prescription for my mother that my father had the doctor prescribe. My mother’s subjugation did not end until my father died. The more I thought about this, the more I kept coming back to our class and those suggestions from UH’s Faculty Senate to “not go there” with assignments after campus carry, and the more firmly I felt that this advice was a mistake. Civil discourse and contentious topics must be addressed in the classroom. I resolved to be more vocal and courageous, which for me included our research projects. By January, I was ready for spring.

January 18, 2017

Unto the Breach, Once More

As cohesively as we worked over the break, I still failed to communicate important details for the course prior to the semester. There was a scheduling error, and the NRA student was signed up for our class again. I had emailed him, but he must not have received it because he was in the classroom on the first day. Clearly, we as faculty partners and WC administrators can make simple changes to support the embedded consultant. I could easily have sent you a copy of the class roster before the first day. It may be rare that we have a student with whom you have had prior conflict, but I cannot know your WC clients and your administrator will not know all of the students you form relationships with in our classes, having a simple list of the students’ names before the first day is a basic step.

The first day is important. I’m more in the limelight and have more responsibility than a start of the term in the WC. I have to learn student names, establish relationships. You are introducing me. In the WC, everyone already knows me. It’s more relaxed and familiar. In the classroom, we don’t have a rhythm yet because the students haven’t settled in. While the course design and assignments are pretty much the same, I need to catch up on your changes.

This is another constructive area for improvement. Perhaps because we have been working together so long, I take for granted that we do not need to meet before the first day of class. Incorporating a pre-semester session to discuss curriculum changes may not prepare you for spontaneous class conflicts or when external events invade your work spaces, but touching base with each other before classes start would, at minimum, allow me to go through the adjustments I made from the previous semester. This is especially important as I add topics that could make students uncomfortable. You may recall that this semester, we tackled Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Jane Elliot, and the Stanford Prison Experiment just on the first assignment. Even after working together over winter break, I didn’t give you the materials for these changes until right before the students had them. You were probably ready for the group project but were unaware that I shifted the course to start with discussions of stereotype and racial justice right out of the break. This pre-planning is not always possible, but I can revise my approach to be more considerate of the time you need to digest the course plan and anticipate student questions.

To be fair, the confluence of events we experienced this last year was somewhat extraordinary, I doubt that most semesters will have as many personal issues or as divisive a national environment. For both of us, the challenges exposed the fact that we don’t have systems in place yet to anticipate tensions and communicate combative experiences when they erupt.

The call to improve our systems provides a clear charge to move us forward from this dialogue.

Yes, along with the acceptance that social justice is not always ideal. We will continue to worry about the new threats to us and our students as rights for women, immigrants, and people of color are still very much at risk; and education is one of the few places working to combat disinformation and bullying to cultivate healthy communities of disagreement.

Final Thoughts and Implications

As we wrap this piece up, it is almost exactly one year since the events of the first shift in our personal, professional, and sociopolitical perspectives. Recounting the timeline, we found that reliving the volatility still disturbed us at times. In choosing an interactive dialogue as the governing design for this article, we invited readers into the discourse, aiming to recreate for them the constant cognitive and emotional work required to navigate these events. Educators experience this labor regularly, but it is exponentially complicated when faculty dedicate course content to confronting spaces of politicized dissensus or respond directly to the breakdown of our national political discourse. We also aim to increase awareness of the complex faculty-consultant relationship in EC programs, and to call for more critical examination of the ways that consciousness-raising and social justice work intensifies the demands on embedded consultants. Faculty partners and WC directors can make structural changes that will anticipate these demands and support ECs.

The first steps are identifying the layers of vulnerability and inconsistent levels of agency that affect EC work. Our current EC program has between two and four faculty-consultant pairs each semester. Ahead of the coming term, we are planning a large meeting with all EC teams and the WC administrator for the program. This session will allow participants to share approaches, to create a pre-semester checklist for exchanging course rosters and materials (Ben Ristow & Hannah Dickinson, 2014), and to consider establishing a programmatic protocol for recording progress and discussing emotional and triggering events. In addition to continuing regular check-ins during the semester, our individual faculty-consultant team will also have a pre-semester meeting to go over planned curricular changes, and we expect to hold a post-semester processing session. In preparation for the end-of-course meeting, the instructor will complete an adapted version of Corbett’s (2015) semester evaluation questionnaire (p. 143), and we will create a separate questionnaire from the consultant’s perspective to give the ECs space to reflect on the semester. Building routine assessment and measures of reflection into our praxis will not guarantee a seamless semester any more than we could promise a conflict-free, safe space for our students, but it will help make sure the EC psychosocial well-being is part of the calculus in creating an effective program.

We accept that using combat or “the breach” imagery is an incomplete frame for this work. Acknowledging the primacy of existing combat metaphors in communication, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson (1980) suggest envisioning argument not as warfare but as a dance. This shared performativity is tempting but implicitly timid. As much as “choreography” went into my students’ civil discourse projects, authentic dissensus is unpredictable. Although discussing argument as war can flatten communication into measures of winners and losers, empowered and silenced, conceiving it as “balanced and aesthetically pleasing” (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, pp. 4-5) denies the embodied anxieties, the very real feelings of being embattled that arise during arguments of significance.

Ultimately, conflicts that occur within the WC are comparatively finite: the session ends, hopefully progress was made, but momentary hostility rarely presents a continual threat or allows for constant strategic revision. In embedded consulting, this ability to engage in ongoing “argument” through civil discourse strengthens our relationship with students and helps ECs learn who they are. Occasionally, they may need to retreat and reorganize in order to clear things and get back to the work. As collaborative agents, we consultants, faculty, and WC administrators cannot shy away from the difficult conversations that make room for this development.

About the Authors

Christal Seahorn is an Assistant Professor of Writing and Digital Rhetoric and Director of First-Year Composition at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. Seahorn earned doctorate in Rhetoric and Composition from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and a Master of Arts in English Renaissance Literature from the University of York, England. Her research areas include Digital Discourse Analysis, Writing Program Administration, and Activist Rhetorics, with concentrations on gender and pre-battle oratory. Her research appears in Queers in American Popular Culture, vol. 2, Folklore Forum, and Type Matters: The Rhetoricity of Letterforms.

Madeline Jones was an embedded consultant at the UH-CL Writing Center and the College of the Mainland Writing Center prior to accepting a full-time tutoring position at the College of the Mainland Writing Center. She has a Master’s in Humanities with a concentration in creative writing and was a recipient of the UH-CL Student Research Award. Presently, she is taking a class in screenwriting.

References

Arao, B & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In L. M. Landreman (Ed.). The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 135-150). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Corbett, S. J. (2015). Sharing pedagogical authority: Practice complicates theory when synergizing classroom, small-group, and one-to-one writing instruction. In Beyond Dichotomies: Synergizing Writing Center and Classroom Pedagogies (pp. 5-23). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

CRAAP Test Model [PDF document]. Retrieved from Alfred R. Neumann Library site: http://libguides.uhcl.edu/PSYC1100/criticalthinking

Eubanks, P. (2001). Understanding metaphors for writing: In defense of the conduit metaphor. College Composition and Communication, 53(1), 92-118.

Faculty Senate, University of Houston. (2016, Jan. 28). Campus carry faculty forum-2016-0.2_01/28/2016 [PowerPoint slide]. Retrieved from http://fs.uh.edu/events.aspx?a=299

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., and Boquet, E.H. (2006). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

Hallman, M. R. & Webster, T. (2017). What online writing spaces afford us in the age of campus carry, “wall-building,” and Orlando’s Pulse tragedy. Handbook of Research on Writing and Composing in the Age of MOOCs, 278-293. Retrieved from http://www.igi-global.com/chapter/what-online-writing-spaces-afford-us-in-the-age-of-campus-carry-wall-building-and-orlandos-pulse-tragedy/172592

Henry, J., Bruland, H. H., & Sano-Franchini, J. (2011). Course-embedded mentoring for first-year students: Melding academic subject support with role modeling, psycho-social support, and goal setting. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 5(2). doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050216

Dad of fallen Muslim soldier’s powerful DNC speech (Khizr Khan full speech) [Video file]. CNN. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/Xzkkk-oJ6bo?t=3m13s

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Leskes, A. (2013). A plea for civil discourse: Needed, the academy’s leadership. Association of American Colleges and Universities. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/2013/fall/leskes

Make your own U.S. Constitution booklet (2014). Constitutionbooklet.com Retrieved from http://constitutionbooklet.com/

Melania Trump and Michelle Obama side-by-side comparison [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RcbiGsDMmCM

Michael, A. (2016, September 8). What do we tell the children? huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/what-should-we-tell-the-children_us_5822aa90e4b0334571e0a30b

Raica-Klotz, H., Giroux, C., Gibson, Z., Stoneman, K., Montgomery, C., Brinson, C., . . . Vang, K. (2014). Developing writers: The multiple identities of an embedded tutor in the developmental writing classroom. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 21-26. Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/raica-klotz-et-al-121/

Riley-Mukavetz, A. (2016, April 20). On working from or with anger: Or how I learned to listen to my relatives and practice all our relations. enculturation.net. Retrieved from http://enculturation.net/on-working-from-or-with-anger

Ristow, B. & Dickinson, H. (2014). (Re)shaping a curriculum-based tutor preparation seminar: A course design proposal. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 102-107. Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/ristow-dickinson/.

S.B. No. 11. (2015). Retrieved from Faculty Senate, University of Houston site: http://fs.uh.edu/documents/events/Texas-2015-SB11-Enrolled012716111454.html

Titus, M. L., Scudder, J. L., Boyle, J. R., & Sudol, A. (2014). Dialoging a successful pedagogy for embedded tutors. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 15-20. Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/titus-et-al-121/

Trimbur, J. (1989). Consensus and difference in collaborative learning. College English. 51(6), 602-16.

Trump’s uncensored lewd comments about women from 2005 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSC8Q-kR44o&feature=youtu.be

Appendix A

Information Literacy Group Project Instructions

Major Assignment 3: Information Literacy Group Project

Module: Writing to Evaluate and Discuss Ideas

WRIT 1301: Seahorn

Rationale—When we discuss literacy in our first major assignment, the Literacy Narrative, we will talk about the relationship between language and power; in essence, the more literate and fluent you are at a certain language or communicative skill, the more power you have to navigate in discourse communities that use and value that language or skill. The Discover Disciplines Project sought to expand your ability to navigate academic communities by interviewing a professor and gaining more insight in a field of interest.

For our next class project, we will continue our focus on academic, analytical writing and turn to a broader consideration of civic engagement. What I am calling “information literacy” for this essay refers to the ability to read public sources critically rather than simply being passive consumers and users of the information. Specifically, we will evaluate texts from various sources for their levels of credibility and reliability.

WRIT1301 is a class built around evidence-based reasoning. As we move toward composing more persuasive writing such as research papers and proposals in Composition II, these more contentious issues will require that students know how to find and evaluate sources of data. Your Comp II instructor will show you how to find scholarly, “peer-reviewed” research, but some of your research will still involve sorting through material available on the public internet. Below are the learning objectives and project instructions.

Assignment Objectives: Personal Responsibility (PR), Critical Thinking (CT), Teamwork (TW)

- Identify the benefits and challenges of collaborative writing activities

- Learn about and participate in civic discourse

- Develop personal responsibility in teamwork, time management, and communication skills

- Learn critical thinking skills for reading and using web-based information

- Tryout new communicative strategies, i.e. dialog writing, formal presentation, and file sharing

- Learn about and apply the CRAAP test for evaluating sources

Writing Skills Evaluated

- Use a library resources page

- Evaluate a fact-checking website for reliability, possible biases, and methodological soundness

- Incorporate and cite web sources correctly

- Construct effective dialogues for civic discourse

- Formulate an annotated bibliography or a literature review

- Compose a Methodologies for an essay paper

Assignment Instructions—For this assignment, students will work in groups of 2-4 people to evaluate a set of publicly-available sources related to a topic. Sources must cover the following areas:

- The US Constitution as a historical primary source;

- 1 evaluation tool, the CRAAP test;

- 1 fact-checking source from our library’s “Background Information & Fact Checking: Other Resources” page as a meta-analysis site;

- 1 editorial, blog-like source; and

- 1 social media source.

Groups will test the credibility of their sources. In class, we will also discuss common elements of public sources that can make them unreliable. Note: the initial task is not to debate a topical issue but rather to evaluate the reliability of sources that make claims about their trustworthiness. Are the sources we use to discuss a topic credible?

Once students have selected their topics and have a foundation on finding and evaluating sources, each group must complete the following required project components.