Andrew Bumstead

Abstract

This paper utilizes data from the University of Utah to explore whether English majors are generally underrepresented at the college writing center in comparison with other majors. The author also analyzes the results to discuss how English departments’ prevailing Romantic idea of writing as an individual pursuit may prevent English majors from visiting the writing center.

Introduction

During the three years I tutored in the WC at Green River College in Washington State, I noticed that students and teachers alike shared what Richard Leahy (1990) describes as a “most persistent image” of writing centers as “remedial facilities for students with ‘special problems’ in writing,” which “conjures up a picture of a skill and drill operation, interested only in grammar, spelling, and punctuation” (p. 44). I have come to expect this particular misunderstanding of writing centers as fix-it-shops, but what surprised me as I started tutoring at the Graduate Writing Center (GWC) at the University of Utah is that students and professors in the English department also hold to this ubiquitous yet erroneous view of writing centers.

This realization dawned on me when I noticed that not one of my writing center clients was an English major. I figured that the only reason for this was that my fellow English majors simply didn’t know about the center or where it was located. In an attempt to rectify the problem, I advertised for the Graduate Writing Center in all of my English literature classes. However, I was surprised when I was met only with blank stares and an utter lack of interest. I spoke with one of my professors about this problem, hoping that I could recruit her as an ally in my quest to generate interest in the Graduate Writing Center. Instead, I was met with indifference when she replied not with hostility but in a matter-of-fact tone, “I don’t know any students in this department that would go to the writing center.” Why, I wondered, was I being met with such resistance by my own peers and colleagues within the English department? As Stephen M. North (1984) notes in his classic essay “The Idea of a Writing Center,”

Misunderstanding is something one expects—and almost gets used to—in the writing center business…But from people in English departments, people well trained in the complex relationship between writer and text, so painfully aware, if only from the composing of dissertations and theses, how lonely and difficult writing can be, I expect more. And I am generally disappointed. (p. 433)

Like North, I found myself disappointed by the attitudes from colleagues and peers in the English department towards the WC. I wondered, however, if my experience was uniquely singular. After speaking with WC tutors from other universities at the Rocky Mountain Writing Center Conference, I discovered that many of them encountered the same resistance, or at the very least apathy, from their own English departments. As a result, I realized that my story was not all that unique. In order to dig further into this seemingly ubiquitous cross-campus problem, I decided it was important to first investigate the issue at my own university.

This paper will explore the data from the University of Utah Writing Center Database in order to determine a) if English majors are in fact underrepresented; b) how English majors’ representation compares with the representation of other majors; and c) the reasons English majors claim to visit the WC. Although these findings are not conclusive, it is my hope that this data will provide a helpful starting point for researching English majors’ apparent lack of interest in the WC.

Site Context

In order for the reader to have a better idea of the particular culture of the WC at the University of Utah, it is necessary to first give a brief description of the physical location. The University of Utah houses two writing centers, the Graduate Writing Center (GWC) and the undergraduate University Writing Center (UWC). The UWC is located on the second floor of the Marriott Library, and is easily accessible to walk-ins because it is situated across from the check-out and drop-off counters. The glass wall at the entrance, though it makes one feel as if they are in a fishbowl, makes the UWC hard to miss for passersby. The GWC, on the other hand, is located on the first floor of the Marriott Library, adjacent to the Graduate Reading Room. It is a tiny, windowless room that is easy to miss. The Graduate Reading Room is only accessible by a key card that must be activated by the workers at the library front desk, so those attempting to enter the GWC for the first time may have difficulty even getting into the room. These physical location details may help to shed light on the specific circumstances that apply to the University of Utah writing centers. In addition, the UWC is funded by student fees and the GWC is funded by the Graduate School, not by the English department as in the case of many other college campuses. It is also necessary to note that the English Department offers both MA and PhD degrees in Literature, Rhetoric and Composition, and Creative Writing.

University of Utah General Population Data

The first question I wanted to explore in my research was whether English majors were underrepresented at the UWC and GWC. In order to find an answer, I had to first begin my inquiry with the University of Utah’s Office of Budget & Institutional Analysis website, where I gathered general data regarding student populations and enrolled majors at the university. The current population of University of Utah students (fall semester 2017) is 31,327, which includes 23,209 undergraduate students and 8,111 graduate students. This was an important number for my research, as I would be deducing the percentage of English majors, as well as a few other selected majors, from this data. The number of English majors between the years 2013-2017 is 385, which comprises 1.2% of the general student population. Of those 385 students, 317 are undergraduates (1.4% of the population), and 68 are graduates (.8% of the population).

The next step was to compare these percentages to the percentages from the University’s Writing Center Database. When searching the database, I used the date parameters from August 15th, 2014 to November 8th, 2017 because those were the dates in which the center’s director, Anne McMurtrey, was overseeing the data, so I could count on the data’s accuracy. The information in the database is divided between undergraduate and graduate students, so I had to search for each group separately. Also, the database tracks the number of appointments as well as the number of clients, so both sets of data are important in this study. In addition, because many of the tutors at the writing center are English majors and are required to take a writing center tutorial as clients as part of their training, I had to subtract one appointment from each of those tutors in order to have a more accurate data set.[1]

English Major Representation

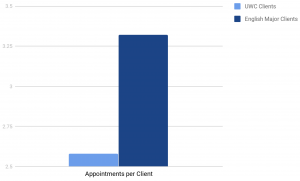

I started with the UWC database and found that undergraduate English majors had 306 appointments (which makes up 2.2% of all undergraduate appointments), and that there were 92 English major clients (1.7% of all undergraduate clients). The English major client percentage (1.7%) in the UWC is slightly higher than the general English major undergraduate population (1.4%). Also, these 92 clients returned to the center for an average of three times. However, the appointment percentage is not significantly higher than the client percentage, meaning that these English major clients are not returning nearly as frequently as many other non-English major clients. That said, when compared to the UWC average, which is 2.58 appointments per client, undergraduate English majors seem fairly well-represented (see Figure 1).

One possible reason for these numbers is that professors of undergraduate classes often require students to visit the UWC for help with lower-order concerns such as grammar and MLA format.

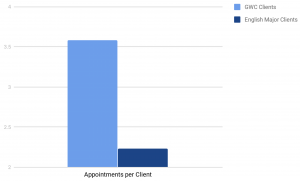

In contrast to the UWC numbers, the GWC results were more striking in comparison, where English majors comprised 13 clients (1.2% of all clients) and made only 29 appointments (.7% of all appointments). Although the percentage of clients (1.2%) is higher than the graduate student population of English majors (.8%), the appointment-per-client percentage was considerably lower than the client percentage. This means that even though the Graduate English major clients return to the center at least once after their initial visits, their return rate is considerably lower than that of the average GWC client, whose average number of appointments is 3.58 (see Figure 2).

When comparing the appointment-per-client averages of English Major clients in both the UWC and the GWC, it appears that the averages basically switch places with each other. As mentioned before, professors of English undergraduate classes often encourage or even require their students to visit the UWC, so this could definitely be contributing to the higher appointment-per-client average amongst undergraduate English majors. Graduate English Major clients, however, do not receive such encouragement to visit the GWC. Perhaps this is one of the reasons this discrepancy exists between English major clients in the UWC and the GWC. Whatever the reason, undergraduate English majors are decently well-represented in the UWC, while graduate English Majors are underrepresented at the GWC, especially in regards to appointments.

Comparison with Other Majors

In order to provide more context, I gathered data on two other majors to compare with English majors: Business Administration and Chemical Engineering. I selected these two majors because Business Administration has the highest representation of clients and appointments in the UWC, and Chemical Engineering has the highest representation of clients and appointments in the GWC.

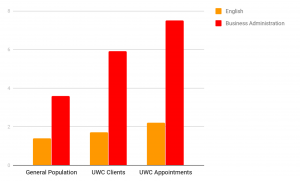

First, I gathered general University of Utah student population data on Business Administration, and I found that Business Administration has 858 undergraduate students (3.6% of the student population). When comparing this percentage to the representation of Business Administration majors at the UWC, the results are striking, as this particular major makes up 296 clients (5.91% of all clients) and 976 appointments (7.51% of all appointments). Not only is the representation of Business Administration clients (5.91%) much higher than the general student population representation (3.6%), Business Administration students are returning to the UWC an average of three times (see Figure 3).

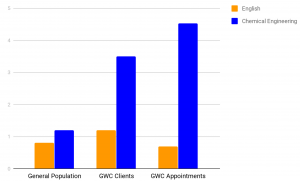

Second, I gathered general University of Utah student population data on Chemical Engineering graduate students and found that there are 105 Chemical Engineering graduate students on campus (1.2% of all students). The representation of this group of students in the GWC is nearly triple the student population percentage, with 36 clients (3.5%). They also made 178 appointments (4.52%), which means these clients made an average of nearly five appointments each at the GWC (see Figure 4).

Why are Business Administration undergraduate students and Chemical Engineering graduate students much better represented at the writing center than English students? One possible explanation is that these two majors attract more international students, a population that tends to take more advantage of the WC services as a general rule. Another reason may be that the students of both of these majors do not consider themselves experts at writing, as English major students might, so they are more willing to seek help with their assignments. This may all be true; however, due to the English department’s emphasis on quality writing and the sheer amount of writing assignments that English majors have, shouldn’t English majors be at least comparably represented at the WC? Shouldn’t we, like Stephen North, “expect more” from those in English departments?

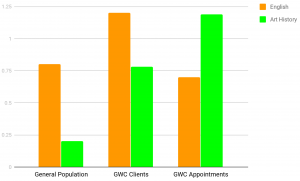

One might argue that the majors examined above, since they are non-humanities degrees, are not all that comparable to English. Therefore, it will be worthwhile to compare the representation of English majors at the WC to another major in the Humanities: Art History. There are only 16 Art History graduate students at the University of Utah (0.2% of the general population compared to English graduate students’ (0.7%). However, despite their small representation on campus, Art History graduate students are actually well-represented in the GWC, with 47 appointments (1.19% of all appointments), and 8 clients (0.78% of all clients). This means that the percentage of Art History clients at the GWC had a much higher number and percentage of appointments than English students (0.7%), even though there are four times as many English students on campus than Art History students. Both majors are in the Humanities, and English majors should in theory be more concerned with their writing assignments. Therefore, the drastic difference between the writing center representation of both majors is quite striking. Even more significant, Art History clients made an average of six appointments compared to English clients’ average of two (see Figure 5).

It has been established then, that English majors are not highly represented in general, especially at the GWC. However, the most surprising finding pulled from the data is that English major clients are returning to the WC at lower-than-expected rates. Why could this be? Are they leaving the WC disappointed that their expectations were not met? If so, what were their expectations in the first place?

English Major Client Expectations vs. Reality

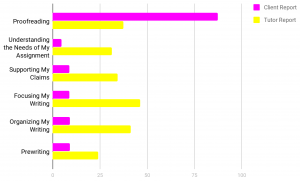

In order to find possible answers to these questions, I turned to another data set in the Writing Center Database. In our database, we track the reasons the clients come to the WC as well as what the tutors report was actually worked on during the session. I wanted to see if there was a discrepancy between what the clients expected they needed help with and what the tutors reported the clients actually needed help with. I was not disappointed. According to the UWC database, when answering the question, “What do you want to work on during this tutorial?”, 87.38% of English major clients reported that they wanted to work on Proofreading. The percentages for the five other categories were drastically lower in comparison: Prewriting (9.22%), Organizing My Writing (9.2%), Focusing My Writing (8.9%), Supporting My Claims (8.9%), and Understanding the Needs of My Assignment (4.75%). Although it is common for all WC clients to want help with proofreading, it is important to note that clients are allowed to click all boxes that apply, and yet most of the English major clients only clicked the Proofreading box.

When comparing this data with the tutor-reported data, we see a large discrepancy. When answering the question, “What did you work on during this tutorial?”, tutors reported that they helped their English major clients with the following, in order of highest percentage to lowest: Focusing the Writing (46.35%), Organizing the Writing (41.2%), Proofreading (37.34%), Supporting Claims (34.33%), Understanding the Needs of an Assignment (31.33%), and Prewriting (24.03%) (see Figure 6).

Although the tutors did help over a third of their English major clients with Proofreading, the percentage was much lower than the 87.83% of the clients that expected to need help with proofreading. In addition, the clients needed help in a variety of other areas that they were not aware of. In fact, according to the tutor reports, Focusing My Writing and Organizing My Writing were the two aspects of writing that the clients needed the most help with, and yet fewer than 20% of the clients had even checked either of those boxes.

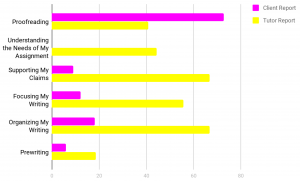

There was a similar discrepancy in the data provided by Graduate English major clients and the Graduate writing tutors. Not surprisingly, Graduate English clients also reported that they needed help primarily with Proofreading (72.72%), followed by Organizing My Writing (18.18%), Focusing My Writing (12.12%), Supporting My Claims (9.09%), Prewriting (6.06%), and Understanding the Needs of My Assignment (0%). The graduate tutors, on the other hand, reported that they actually helped their English major clients with the following: Organizing the Writing (66.67%), Supporting Claims (66.67%), Focusing the Writing (55.56%), Understanding the Needs of the Assignment (44.44%), Proofreading (40.74%), and Prewriting (18.52%) (see Figure 7).

All of this data shows that a high majority of English majors wanted their papers proofread but didn’t see much need for other areas of concern, such as Focusing My Writing or Supporting My Claims. However, the clients drastically underestimated their writing needs in all categories except for Proofreading, which they overestimated as their top priority. Most surprisingly, none of the clients reported needing help with Understanding the Needs of My Assignment, yet the tutors reported that in reality, 44.44% of their clients needed help understanding their assignments.

Although it’s common for all visitors to the WC to click the Proofreading box primarily, English majors should theoretically understand the writing process and how the WC can help them in that process. However, as this data shows, English majors unfortunately don’t seem to want help, or at least don’t think they need help, with what Reigstad and MacAndrew (1984) call “Higher-Order Concerns” (p. 11). Perhaps, then, we should no longer assume that English majors understand the purpose of the WC any more than students in other majors.

Limitations and Future Research

This paper provides a starting point for further discussion regarding English major representation at the college writing center. However, the research in this paper is limited to the University of Utah UWC and GWC databases. Due to this small sample size, it would be worthwhile to explore this topic by gathering data about English major representation from other college WC databases and comparing them to these findings from the University of Utah. Furthermore, interviews and surveys will need to be conducted in order to better answer why English students do not visit the writing center more often, why clients do not return more often, and why clients do not seem to understand their own writing needs. It is my hope that as a result of future research, we can discover better ways to attract English majors to the WC so they will more greatly benefit from its services.

Conclusion

Based on this data, it seems that English majors either don’t understand the purpose of the WC or they don’t understand what they actually need help with (or, perhaps more likely, both). This is surprising when considering that they should be more aware of their own writing strengths and weaknesses, as writing is central to English department curriculum. So where did this gap in understanding come from? Lisa Ede (1989) theorizes that “The assumption that writing is inherently a solitary cognitive activity is so deeply ingrained in western culture that it has, until recently, largely gone unexamined…[T]hose who most resist or misunderstand the kind of collaborative learning that occurs in writing centers are often our own colleagues in departments of English” (pp. 7-8). As a graduate English major, I agree with this theory. The Romantic view of writing in the English department as a “solitary cognitive activity” likely affects the way English major clients, especially graduate students, view the writing center as a “fix-it-shop” and not a collaborative place that provides “the readily available, intensive, and long-term writing support in ways that advisors often cannot” (Snively, Freeman, & Prentice, 2006, p. 155). It may also explain why English majors are less willing to make changes to their paper due to the Romantic idea of writing as an individual pursuit, since proofreading is impersonal while higher-order concerns are not.

Despite the ubiquitous notion of writing as a solitary activity and the writer as a reclusive Romantic, those of us who know the real purpose of the WC should not simply throw up our hands and walk away. To provide a more hopeful counterexample to the anecdote I shared at the beginning of this paper, I met with another professor in the English Department and mentioned the work that I conducted on the lack of English major representation at the UWC and GWC. This professor, who has been teaching at the University of Utah for many years and is preparing to retire soon, had no idea that a GWC even existed and was dumbfounded. This gave me an opportunity to explain to him the purpose of both the UWC and the GWC as not simply fix-it-shops, but resources where writers can collaborate with tutors on any aspect of their writing. Emboldened by his now more accurate understanding of writing centers, this professor enthusiastically advertised the GWC in his graduate classes. I was also encouraged by the encounter, which demonstrated to me that simply clarifying misunderstanding about the WC can generate more support from those who seem at first to be indifferent our efforts—even among peers and colleagues in English Departments.

Reference List

Ede, L. (1989). Writing as a social process: A theoretical foundation for writing centers? The Writing Center Journal, 9(2), 3-13.

Leahy, R. (1990). What the college writing center is—and isn’t. College Teaching, 38(2), 43-48.

McAndrew, D. & Reigstad, T. (1984). Training tutors for writing conferences. U.S. Department of Education.

North, S. M. (1984, September). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446. Office of Budget & Institutional Analysis: Enrolled Majors. Retrieved from Obia.utah.edu.

Snively, H., Freeman, T., & Prentice, C. (2006). Writing centers for graduate students. The Writing Center Director’s Resource Book. C. Murphy (Ed.) Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

University of Utah Writing Center Database. Retrieved from Utah.mywconline.net.

Notes

- It is important to note here that I made two appointments for myself at the GWC during Fall Semester 2017 prior to Nov. 8th. Because I was not required to make those appointments as part of my training, I included those two appointments as part of the GWC data set. ↑