Leanne Moore

Abstract

While writing center scholarship has explored useful methods for helping the university-level English language learner (ELL) as well as the high school writer, there is little scholarship examining how writing centers can serve the high school ELL population. While university students must succeed in their university classes, high school students in 42 states must succeed within the Common Core English Language Arts classroom. The differing requirements between the two make it important to focus on the specific needs of peer writing tutors working with high school English language learners. This article applies Stanford University’s Understanding Language Initiative’s “Six Key Principles for ELL Instruction” to the high school writing center as a means of facilitating peer tutors to help the ELL writer with Common Core-based writing assignments. Each principle is examined in turn to consider the ways each intersects with previous writing center scholarship to help the high school English language learner.

Keywords: high school writing centers, Common Core, English language learners

Writing center scholarship has explored fruitful practices for helping non-native English speaking students at the university level (Bell & Youmans, 2006; Blalock, 1997; Bruce & Rafoth, 2009; Chiu, 2011; Enders, 2013; Nakamaru, 2010; Nan, 2012; Powers, 1993; Vallejo, 2004; Weirick, Davis, & Lawson, 2017). A growing number of resources seeks to provide guidance for the high school writing center director (Ashley & Shafer, 2006; Childers, 1989; Fels & Wells, 2011; Tobin, 2010; Upton, 1990). However, no such examination has been made of best practices for helping English language learners (ELL) in their high school writing center. While existing scholarship on both university non-native English writers and the high school writer can be applied to the ELL high school writer, an added complication for high school ELLs exists in the form of the Common Core English Language Arts Standards. Rather than achieving university requirements, high school ELL students in 42 states (and in a growing number of English-medium secondary schools in other countries) must succeed within the Common Core classroom. The differences between university requirements and the requirements of the Common Core make relying on existing writing center scholarship inadequate. For example, with the narrow exception of remedial classes, many writing requirements at the university level assume students have mastered the kinds of writing skills students learn in high school.

While Common Core writing skills are meant to prepare students for university, high school students command only emergent skills in these areas. English language learners contend with even greater challenges, as many do not possess the language skills that their university counterparts have had to prove through entrance exams like the TOEFL. Therefore, targeted, specific guidelines regarding the high school ELL tutoring session are needed to help this demographic make greater academic gains. Currently, only one article outlines the connection between the high school writing center and the Common Core English Language Arts Standards (Horan, 2015), and it does not address ELL students’ specific needs. With 4.6 million non-native English speakers in public schools across the United States (National Center for Education Statistics, 2017), not to mention the 40% increase in the last five years in the number of English-medium high schools across the globe, many of which are beginning to adopt a U.S. curriculum (Morrison, 2016), supporting ELLs with Common Core-based writing assignments is imperative.

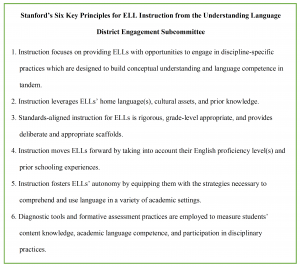

As the director of a writing center serving a population of 100% ELLs in an English-medium high school in Guangzhou, China, that adheres to the Common Core State Standards, I have asked myself how my tutors can best help their clients. To address this gap in knowledge within my own writing center, I applied research from Stanford University’s Understanding Language Initiative, synthesized in a document entitled “Six Key Principles for ELL Instruction” (Stanford Graduate School of Education, 2013). These six principles are guidelines that seek to help instructors plan their curriculum in a way that allows language learners to access Common Core-based content at the same time they build English language competency. Figure 1 below lists the six principles, and the article then continues with a consideration of several strategies that high school writing center peer tutors who serve ELL students—within the U.S. or abroad—can use to alleviate some of their biggest challenges as they implement the six principles in their sessions.

Principles One and Two have proven to be the least challenging to implement in the writing center. Principle One indicates that classroom instruction ought to give ELLs the opportunity to talk about discipline-specific topics and concepts in English so as to build both understanding of the content area and understanding of the English language simultaneously. Principle Two advises instructors to use ELLs’ home language, culture, and background knowledge to build off of what students already know, thereby providing them with a firm foundation on which to construct new knowledge. The nature of writing center work has meant that in its simplest form, tutors help clients build both content and language knowledge by talking about an assignment in English. Likewise, because my tutors are Mandarin speakers, they can easily leverage clients’ home language by speaking Mandarin as necessary, a practice already shown to be effective in the writing center (Ronesi, 2009) and which U.S. directors can implement by recruiting multilingual writers from within their schools. I have found the principles that most challenge my tutors are Three through Six.

Principle Three states that instruction should put scaffolds in place to help ELLs reach grade-level standards (Donato, 1994; van Lier & Walquí, 2012). In a 2014 article, John Nordlof notes that there are two fundamental types of scaffolding that occur during writing center sessions, those of cognitive scaffolding and those of motivational scaffolding. In cognitive scaffolding, the tutor helps the clients discover problems on their own. Examples of this kind of tutor talk are prompting students with open-ended questions, responding to essays as a reader, and demonstrating a concept, among others (Mackiewicz & Thompson, 2014, p. 68). In motivational scaffolding, the tutor helps to create a supportive learning space for clients. Examples of this kind of tutor talk include showing concern for the client, praising a client, showing sympathy or empathy, and reinforcing a client’s ownership of their essay (Mackiewicz & Thompson, 2014, p. 71).

To help scaffold our own clients in the ways mentioned above and thereby implement the third principle, I train tutors to employ each of these methods during their sessions. The real challenge for our tutors’ ability to scaffold, however, comes in knowing which of these methods to use and when to use it. To help our students make these decisions, my co-director and I developed a flow chart (Figure 2) that we post in the writing center. Tutors can refer to it as their sessions unfold so that they can make appropriate scaffolding decisions. As tutors and clients then engage in conversations between real readers and writers, clients receive reinforcement when they do well and empathetic guidance where they fall short. In so doing, tutors can effectively implement the third principle to scaffold students to achieve the next level of competence toward full proficiency in the standards.

While scaffolding students, whether through cognitive or motivational methods, can lead students to success, knowledge of students’ previous experiences are equally as important to aiding clients. In considering background knowledge, Principle Four is twofold: It states that instruction should “[move] ELLs forward by taking into account [both] their English language proficiency level(s) and prior schooling experience” (Stanford Graduate School of Education, 2013). Because I work in a Chinese writing center, where all students speak Mandarin but learn English, we have the advantage in that our tutors share the same home language as their clients. To meet the first injunction, then, that of taking the language ability of clients into account, I encourage the tutors to use Mandarin in their sessions as necessary, as mentioned under Principle Two (Ronesi, 2009). However, Principle Four helps tutors to be thoughtful and intentional about when to use Mandarin and when to use English with their clients.

To help tutors make these kinds of decisions, I guide discussions during training to help tutors understand the purposes that they have for using each language. Many of our students, particularly those in grades seven through nine, do not have the language proficiency to show the depth of thought required for their assignments. While certainly a challenge for these students, it also presents a challenge for our tutors, whose job is to help them overcome these kinds of hurdles. When they are helping a client of a lower English ability, it may be more helpful for the client to converse in Mandarin so that their thoughts can flow freely, uninhibited by an unfamiliar medium of communication. However, when the client is capable of expressing themselves with relative ease in English, it can be more helpful to hold a session in English for the same reason, to encourage a freer flow of thought than is able to happen when energy is spent translating ideas back and forth between the two languages. Following Peter Carino’s (2003) advice to take a more directive approach with inexperienced writers, I have trained tutors to use Mandarin more with younger learners (grades seven through nine), and English with more advanced learners (grades 10 through 12). An additional guideline I have given tutors is that if a client of any grade level seems unwilling or unable to engage very deeply in a conversation in English, switch to Mandarin to ensure that language is not the main barrier in conversation. Using Mandarin and English strategically in this way helps to support our students with one of their toughest challenges as language learners (Ronesi, 2009). For high schools in the U.S., the implication of this principle is that directors may find it helpful to prioritize finding multilingual tutors from within their student body.

In addition to knowing how and when to use English or Mandarin to address the language needs of clients, tutors must also take into account the client’s prior formal education. For example, there is a difference between the way our students have been taught to write an essay in their Chinese public schools and the way Western academic readers will expect to read an essay. Because our students attend the school in order to prepare themselves to succeed in a Western academic environment, we must train tutors to address these differences. A basic understanding of contrastive rhetorical theory can aid us in this endeavor (Quinn, 2012). We take a direct look at some of the differences in the expectations between Western academic essays and Chinese academic essays during training, allowing tutors to take on a more directive role as is appropriate for working with language learners and as tutors who have more knowledge in the subject area (Carino, 2003; Nan, 2012). In their sessions, they can then say to a client, for example:

You have stated your point very clearly here, and Chinese academic readers will expect that you make your ultimate point here at the end. But in a North American essay, your readers are going to expect you to tell them the main point in a thesis statement at the beginning of the essay before the actual argument. You could move this sentence to the introduction to help your readers be less confused.

Pointing out these differences is a way our tutors can address students’ previous academic formation.

Conversely, our clients’ previous education can also serve as a well-aligned foundation to their current learning. Tutors can show the similarities between what they have been required to do before and what they are required to do for their present assignments. For instance, Chinese writing education has traditionally taught students to use others’ writings as a model and a scaffold for learning to write well. The citation of those words is not considered necessary in student writing (Chou, 2010, p. 38). This can result in what the North American academy considers plagiarism. To help their clients learn citation rules, our tutors can take what our students already know—that using someone else’s words can be useful to one’s own writing—and add to it the idea that in the West, one must give credit to the original writer for the use of those words. This kind of tutor talk uses the client’s knowledge of essay writing for one particular audience to help him be a more flexible writer who can reach audiences across cultures (Ede & Lunsford, 1984). These two strategies of intentionally noting both the differences and similarities between clients’ previous education and their current education helps our tutors to make use of what the client already knows. Principle Four does not require that tutors speak the same native language as their clients, and for that reason, it is easier to implement in U.S. high school writing centers than Principle Three. Writing center directors simply need to introduce their tutors to basic contrastive rhetoric in order to give them the tools they need to successfully implement Principle Four.

While taking background knowledge and scaffolding methods into consideration during sessions, writing center tutors must also remember that the purpose for those strategies is to help the clients make independent choices in their writing. Principle Five encourages educators to foster their students’ autonomy by giving them strategies to understand and use language for their needs (Stanford Graduate School of Education, 2013). Writing centers can implement this principle by training tutors to let clients maintain control of their autonomy during a session. During tutor training, I make a point of reminding tutors to let the client hold the pencil (with the one exception being during a brainstorming session when it may be helpful for the tutor to have the pencil and write down the client’s ideas as they are speaking) (Bruffee, 1984; Clark, 1990; Cogie, 2001; Shamoon & Burns, 1995). For many students in both domestic and international settings who have been accustomed to a teacher-centered classroom, this can feel awkward at first (Nan, 2012) and has proven to be a stumbling block for my tutors, who automatically pick up a pencil when their sessions start. This may be to help themselves feel more confident, assuming the role of the authority figure they sometimes feel they need to be. Indeed, clients do come in expecting that they will be told what to write and how to “fix” their papers. However, with explanations for the reasons to hand over the pencil to the client, a visual reminder on the flow chart posted in the center to let the client hold the pencil, as well as increased self-efficacy after several sessions, tutors gradually become more comfortable in the role of a peer. They remember to hand over the pencil to the client at the beginning of a session, a sign and a symbol of handing the power over to the client. Another option may be to simply remove pens or pencils from the writing center, forcing clients to get out a pen or a pencil themselves. When clients are the ones writing the most, it, in effect, puts them in charge of the session, fostering their autonomy (Brookes, 1991). Reminders, both verbal and visual, can help reinforce this practice in our tutors so that ELL students have full autonomy over their learning.

Finally, although writing center tutors want their clients to have autonomy and independence in their learning, writing centers are always necessary for writers of all levels to receive formative feedback. Principle Six states that teachers should use formative assessment to measure a student’s content knowledge and language competence (Stanford Graduate School of Education, 2013). In their article “Formative Assessment and the Paradigms of Writing Center Practice,” Joe Law and Christina Murphy (1997) highlight the ways that formative assessment and writing center theory intertwine. They write, “The almost century-long history of writing centers attests to an inquiry-based, individualized pedagogy directed toward the primary aims of formative assessment in providing in-process commentary that offers direction, guidance, and analytical critique to emerging writers” (Law & Murphy, 1997, p. 106). We can train our tutors to serve as a step in this process by being real readers who ask real questions of their clients’ essays. What parts do they find confusing? Where do they feel more information might be helpful? Has the writer satisfied all the reader’s doubts about the topic at hand? What parts does the reader find interesting, insightful, surprising, or particularly well said? This, in effect, helps the writer see what they have done well, plus where they can continue to improve, and is common writing center practice.

Our tutors, however, were hesitant to implement these strategies due to their lack of self-confidence. Coming from an educational environment in which the teacher has always been seen as the center of authority and knowledge, our tutors found it difficult to believe that they had anything to offer their fellow students. They feared that if they read a student’s paper and felt confused, it was an indication that they as tutors were not smart enough or competent enough. This is another area in which contrastive rhetorical theory can be useful, specifically to talk about the differences between a reader-centric and a writer-centric culture. In some cultures, if a reader is confused, it is often an indication that the reader must spend more time pondering the writer’s thoughts. However, in other cultures, the tendency is the opposite. If readers are confused, it is an indication that the writer should explain more clearly (Connor, 2002). While contrastive rhetoric is more complicated than such brief explanations can fully present, an introduction to the idea can help our tutors to know that if they are confused, it is worthwhile to bring this to a client’s attention as a way of focusing the client on places of possible improvement. Such instruction has helped to give our clients more confidence in their ability to provide feedback, especially before they have the opportunity to develop the self-efficacy experience can provide. Tutors both in the U.S. and abroad may find themselves lacking the confidence to provide feedback for a variety of reasons, and an exploration of reader-centric and writer-centric cultures can help give tutors the confidence they need to provide astute, honest feedback to clients that provides the formative assessment so necessary to ELL academic success.

As Common Core standards create expectations for college readiness that are ever more rigorous, students who must learn both English and the objectives of their content classes face heavy obstacles to success. Support from many areas is necessary to provide them an effective learning environment. The Six Principles help guide instruction in and out of the classroom so that ELLs can reach proficiency in the standards, and writing centers can play a significant role in supporting the implementation of the Six Principles at a school-wide level. With tutor training that comports with the Six Principles and gives tutors strategies to overcome challenges to their implementation, high school writing centers can offer a strong locus of support for ELLs, equipping them to participate and succeed in a Westernized, North American academic playing field.

References

Ashley, H. M., & Shafer, L. K. (2006). Writing zones 12.5: Regarding the high school writing center as a gateway to college. Clearing House, 80(2), 83-85. doi: 10.3200/TCHS.80.2.83-85

Bell, D. C., & Youmans, M. (2006). Politeness and praise: Rhetorical issues in ESL (L2) writing center conferences. Writing Center Journal, 26(2), 31-47.

Blalock, S. (March 12-15, 1997). Opening the locks: Centering literacy and ESL in the writing center. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication. Phoenix, AZ. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED416475.pdf

Brookes, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. Writing Lab Newsletter, 15(6), 1-4.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth, B. (2009). ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Bruffee, K. (1984). Peer Tutoring and the ‘conversation of mankind.’ College English, 46(7), 635-652.

Carino, P. (2003). Power and authority in peer tutoring. In M. A. Pemberton & J. Kinkead (Eds.), The Center Will Hold (96-113). Logan, Utah: USU Press.

Childers, P. B. (Ed.) (1989). The high school writing center: Establishing and maintaining one. Urbana, IL.: National Council of Teachers of English.

Chiu, C.-H. (2011). Negotiating linguistic certainty for ESL writers at the writing center (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Chou, I. C. (2010). Is plagiarism a culture product: The voice of a Chinese-speaking ELL student. International Journal-Language Society and Culture, 31, 37-41.

Clark, I. (1990). Maintaining chaos in the writing center: A critical perspective on writing center dogma. Writing Center Journal, 11(1), 81-93.

Cogie, J. (2001). Peer tutoring: Keeping the contradiction productive. In J. Nelson and K. Evertz (Eds.), The Politics of Writing Centers (37-49). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Heinemann.

Connor, U. (2002). New directions in contrastive rhetoric. TESOL Quarterly, 36, 493–510.

Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf and G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian Approaches to Second Language Research (33-56). New York: Ablex.

Ede, L., & Lundsford, A. (1984). Audience addressed/audience invoked: The role of audience in composition theory and pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, 35(2), 155-171.

Enders, D. (2013). The idea check: Changing ESL students’ use of the writing center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 37(9/10), 6-9.

Fels, D., & Wells, J. (2011). The successful high school writing center: Building the best program with your students. Language & Literacy Series. New York: Teachers College Press.

Haaland, M. (2016). Writing center guide. Nansha College Preparatory Academy, Nansha, China.

Horan, T. (2015). The Common Core and your school library writing center. School Library Monthly 31(7), 5-7.

Law, J., & Murphy, C. (1997). Formative assessment and the paradigms of writing center practice. The Clearing House, 71(2), 106-108.

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2014). Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies, 42(1), 54-78.

Morrison, N. (2016, June). International schools market expected to hit US$89 billion in 2026. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickmorrison/2016/06/29/international-schools-market-to-hit-89bn-by-2026/#6c29997870e3

Nakamaru, S. (2010). Lexical issues in writing center tutorials with international and US-educated multilingual writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 19, 95-113. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2010.01.001

Nan, F. (2012). Bridging the gap: Essential issues to address in recurring writing center appointments with Chinese ELL students. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 50-63.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). English language learners in public schools. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp

Nordlof, J. (2014). Vygotsky, scaffolding, and the role of theory in writing center work. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 45-64.

Powers, J. (1993). Rethinking writing center conferencing strategies for the ESL writer. Writing Center Journal, 2, 39.

Quinn, J. (2012). Using contrastive rhetoric in the ESL classroom. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, 40(1), 31-38.

Ronesi, L. (2009). Theory in/to practice: Multilingual tutors supporting multilingual peers: A peer-tutoring training course in the Arabian Gulf. Writing Center Journal, 29(2), 75-94.

Shamoon, L., & Burns, D. (1995). A critique of pure tutoring. Writing Center Journal, 15(2), 134-151.

Stanford Graduate School of Education. (2013). Understanding language: Language, literacy and learning in the content areas. “Six key principles for ELL instruction.” Stanford, CA.

Tobin, T. (2010). The writing center as a key actor in secondary school preparation. Clearing House, 83(6), 230. doi: 10.1080/00098651003774810

Upton, J. (1990). The high school writing center: The once and future services. Writing Center Journal, 11(1), 67-71.

Vallejo, J.F. (2004). ESL writing center conferencing: A study of one-on-one tutoring dynamics and the writing process. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA.

van Lier, L., & Walquí, A. (2012). Language and the Common Core State Standards. Paper presented at the Understanding Language Conference, Stanford University. Stanford, CA., Retrieved from http://ell.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/academic-papers/04-Van%20Lier%20Walqui%20Language%20and%20CCSS%20FINAL.pdf

Weirick, J., Davis, T., & Lawson, D. (2017). Writer L1/L2 status and asynchronous online writing center feedback: Consultant response patterns. Learning Assistance Review (TLAR), 22(2), 9-38.