Olivia Buck

Abstract

Writing center research has explored writing center professionals’ perceptions of tutorial success and satisfaction through a variety of means, yet writers’ perspectives have rarely been investigated. This IRB-approved study has been designed to seek insight into students’ prior knowledge (Bransford, Brown, Cocking, 2000) of the writing center’s goals and functions by analyzing pre-tutorial questionnaires and conducting semi-structured post-tutorial interviews. An interview with an experienced tutor was also conducted for comparison of perceptions. This study begins to investigate students’ prior knowledge about the writing center’s goals and practices that they bring to their tutorial sessions. Secondarily, I was interested in where students derive their perceptions of the writing center’s goals and purpose. The research revealed that most students do not have a clear idea of what the writing center’s purpose is or how the sessions will go. Even though the students knew that they would receive help with their work, they did not know how this would be achieved. Most students indicated that when they arrived, they were interested in creating “better” texts and that they had been directed to the writing center by an authoritative figure, such as an instructor or advisor.

Keywords: Undergraduate students, perceptions, peer tutoring, writing, writing center

Introduction

When I was a tutor-in-training, I observed a session with an experienced tutor in which the first-visit student we were working with wanted to review a personal statement for a Master’s program at another university. When she came into the session, she told us that she wanted us to correct her grammatical errors. She also mentioned that the personal statement was important to getting into this program. The tutor noticed that although her personal statement was creative, it did not adhere to the requirements of the genre and the argument did not match her thesis. When the tutor mentioned that she might want to take a look at those things as well, she argued that she just needed to have her grammar corrected. Although the tutor tried to balance her goals with trying to communicate the aspects of the text that he noticed, she became frustrated. She was so set on the idea of the writing center being an editing service or a “fix-it shop” (North, 1984) that the session became a little tense. Although this session could have been handled differently, it appears that the issue stemmed from the difference in expectations from the tutor and the writer (Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Raymond & Quinn, 2012). The writer had come to the writing center expecting one service, but the tutor was offering her something else. Observing this session made me wonder what students understand about the writing center before coming in for their first session. It was this question that I hoped to gain insight from in order to better understand the students and ideas entering the writing center on their first visit.

According to Muriel Harris (2010) in “Making Our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric,” the manner in which we describe ourselves to our communities has not conveyed the message that we hope to send. She argues that although we aspire to be a service that encourages writing development, we have utilized outreach methods that have fostered the very perceptions of the writing center that we wish to avoid being associated with (Harris, 2010, pp. 54-55 & p. 58). The writers we serve have expectations of the service that is being provided to them. When these expectations are not being met, like for the writer mentioned above, it can be an understandably frustrating experience for the writer. At times, our goals may not align with the goals of the student (Harris, 2010, p. 69), but this may partially come from the way that we frame our purpose and goals to the communities we serve (Harris, 2010, p. 69). Our desire should not just be to define ourselves but also to acknowledge the expectations of the writer and endeavor to aid them in understanding what services we will provide to them.

In the service of our self-definition, writing center scholarship has widely engaged professionals’ –tutors’ and directors’–perceptions of the writing center through the production of both lore and empirical research. Seemingly, from Stephen North’s (1984) “The Idea of a Writing Center” sprang numerous other attempts to unlock writing center professionals’ understanding of the writing center. Professional lore often paints writing centers as inviting places where students receive holistic help with their writing (McKinney, 2013). Within the writing center, lore has taken shape despite not always having empirical research to support the ideas. Further, writing center scholars have begun to demonstrate that this definition of the writing center may not be accurate to all those who participate in its services (McKinney, 2013). Writing center professionals use lore and research to interpret the writing center’s goals, functions, and practices. Our students do not have the same exposure to these ideas. Therefore, their definitions or perceptions of the writing center’s goals, functions, and practices may be very different from ours. Scholarship in our field must be based in empirical research, as opposed to lore and anecdotal sources, to ensure that our understanding of students’ perceptions is accurate. However, the perceptions of the writing center belonging to one of its largest stakeholders – the student –are not investigated often enough.

Although in recent years, writing center researchers have noticed this gap and attempted to address it (Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Cheatle & Bullerjahn, 2015; Morrison & Nadeau, 2003; Raymond & Quinn, 2012; Thompson et al., 2009; Thonus, 2001), there are still remarkably few empirical studies that have looked into the perspective and ideas of students. Recent research regarding the student perspective has predominantly explored various aspects of tutorial satisfaction and interpretations of success. For example, Rebecca Day Babcock and Terese Thonus (2012) evaluated the various methods of understanding tutorial success through the previous literature within the field. These methods included ideas such as “helping the writer revise his/her project for the better” and “helping the writer get a better grade on his/her project” (p. 145). The authors asserted “perceptions of success may be different from actual success depending on audience and criteria” (Babcock & Thonus, 2012, p. 153). Therefore, the perceptions of all those involved in the writing center community are varying. In response to the multiplicity of perceptions, the authors called their audience to do further empirical research in order to better understand the various perceptions of the writing center. The present study was inspired by Babcock and Thonus’ (2012) research, which encourages a “big picture” view of the writing center. In order to understand the writing center, or “success” within it, we must pursue knowledge of the various viewpoints of those who use, and therefore define, it.

One recent study has examined the perceptions of the writing center belonging to the students on the campus of their university. In this study, Joseph Cheatle and Margaret Bullerjahn (2015) endeavored to better understand how students perceive the writing center. Through multiple choice surveys and interviews, the piece investigated the demographics at the writing center in comparison with the targeted audience for its services. Additionally, it explored the students’ perceptions on why others choose not to attend the writing center. The authors found that most students believed that the writing center was designed for first-year or international students and that the majority of students who do not partake in the writing center’s services believe that it is not necessary for them. However, the study did not place an emphasis on how students interpret the goals, practices, and functions of the writing center or from were those perceptions where derived.

Additionally, very few studies focus on first-visit students in their pursuit of understanding the perceptions of the writers we serve. In my search, only one source mentioned first-visit students. In Thonus’ (2001) “Triangulation in the Writing Center: Tutor, Tutee, and Instructor Perceptions of the Tutor’s Role,” the distinction between first and multiple-visit students was briefly touched upon. However, since there was only one first-visit student in the study, no data could be supported in the results. It does, however, illustrate that first-visit and multiple-visit students may have differing perspectives. The lack of research regarding the perceptions of first-visit students is a gap that I wish to begin to gather insight into through this study.

In this study, student perceptions of the writing center have been explored in hopes to extend the previous research about the ideas and perceptions of students. My goal has been to begin to understand how first-visit students perceive our writing center. Therefore, I strived to answer the research question: What does the undergraduate, first-visit student know about the writing center before and after their first session? This study used a framework established by John D. Bransford, Ann L. Brown, and Rodney R. Cocking (2000), which states that students approach their learning environments with various forms of prior knowledge that affects how they interpret new information; therefore, education professionals must understand and engage students’ prior knowledge for effective learning to occur. My study begins to investigate the prior knowledge students bring to the writing center. Secondarily, I was interested in where students derive their perceptions of the writing center’s goals and purpose. Finally, according to Isabelle Thompson (2006), writing center research benefits from collecting and analyzing empirical data through assessment at local sites and offers opportunities for reflection in the day-to-day processes at the writing center. Therefore, in my research, I have endeavored to offer implications for possible use and expansion of the methods and ideas of this study for use not only in our local context, but also in other writing center contexts.

This IRB-approved study used a pre- and post-model, analyzing pre-tutorial questionnaires and conducting semi-structured post-tutorial interviews that could be replicated at other universities and in other contexts. Participants of the study were first-visit undergraduate students and one writing center tutor who was included in order to understand how an experienced writing center consultant interacts with first-visit students. This research about first-visit students’ perceptions of the writing center has implications for writing center research and practices. Tutors can better understand the incoming perspectives of writers and adjust their tutoring styles and techniques to better aid students during tutorials (Bransford et al., 2000). Writing centers can also adapt new strategies of outreach to inform students of its goals and purpose (Harris, 2010). The results revealed that most students do not have a clear sense as to what the writing center’s purpose is or how the sessions will go—although the students knew that they would receive help with their work, they did not know how this would happen. Most students indicated that when they arrived, they were interested in achieving “better” texts and that they had been directed to the writing center by an authoritative figure, such as an instructor or advisor.

Literature Review

In order to conduct this study, I looked at two important components of student learning and writing center experience. First, I searched for findings in educational cognitive research, specifically to answer the question of how students interpret their learning environments. Second, I searched for prior writing center scholarship that empirically studied the student perceptions of the writing center, particularly seeking out studies that investigated first-visit students.

Prior Knowledge

This study has been informed by the educational framework presented by Bransford et al. (2000) in How People Learn. Bransford et al. (2000) discussed the evolution of cognitive research as it applies to education. The evolution of the research has led to remarkable discoveries that can help teaching across formats, such as studies regarding the “design and evaluation of learning environments” and “[r]esearch on learning and transfer” (Bransford et al., p. 4). Bransford et al. made this assertion by saying that although the research presented in this first chapter discussed primarily younger students –specifically K-12 – it is indeed just as relevant for college-age students (p. 27). The idea that older students have prior knowledge that changes how they perceive the information that they encounter in their learning environment seems clear. Additionally, although Bransford et al. focused on the classroom setting, their framework is applicable in other learning environments as well. As writing center lore supports, the writing center is ideally a place of writing development, and therefore, a learning environment. Therefore, Bransford et al.’s goal of designing appropriate learning environments, indeed, applies to writing centers as well.

Bransford et al. (2000) described what they have termed pre-existing (or prior) knowledge within a learning environment. Their assertion was that prior knowledge, the ideas and understandings that each learner brings with them into the individual learning environment, has a definite effect on how a student learns. In other words, the prior knowledge that learners are bringing with them helps them interpret not only the information that they are being told, but also the learning environment itself. According to Bransford et al., students approach their education with “a range of prior knowledge, skills, beliefs, and concepts that significantly influence what they notice about the environment and how they organize and interpret it” (p. 10). Although Bransford et al. predominantly focused on the role of prior knowledge in content teaching and learning, I have focused on the less emphasized aspect of prior knowledge in regards to how students perceive a learning environment and how those perceptions influence their subsequent experience of that environment. Bransford et al. further argued that it is important for education professionals, in this case, whether instructors or tutors, to keep their students’ “incomplete understandings, false beliefs, and naive renditions of concepts” in mind as they are approaching an educational scenario with their students (p. 10). Therefore, students never approach a learning environment as empty vessels prepared to be filled; they come in with prior knowledge, which may or may not be accurate, that the educator must not only be aware of, but also negotiate with.

Furthermore, in the classroom setting, instructors need to understand students’ conceptual prior knowledge. Although Bransford et al. (2000) originally discussed the concept of prior knowledge in K-12 classroom settings, the same idea is true of the writing center. Prior knowledge particularly has implications for writing centers, as students are coming into the environment and their tutorial sessions with not only their ideas of how to accomplish their writing tasks, but also ideas about how the tutorial session is supposed to go and what the writing center is supposed to do. Therefore, writing center professionals must negotiate with not only students’ prior knowledge of their writing practices and processes, but also with their prior knowledge of the writing center itself. The way that students interpret the goals and functions of the writing center may change how students interpret their experiences within the writing center.

Whose “Idea of the Writing Center?”

Prior research has frequently focused on writing center professionals’ perceptions of the writing center and its goals. From North’s (1984) “Idea of a Writing Center” to more recent pieces like Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s (2013) Peripheral Visions of the Writing Center, scholarship has repeatedly discussed insiders’ perceptions (or, in the case of McKinney, reductive narratives) of the writing center. However, a few pieces published in the last several years have pointed out that understanding the perspective of writing center professionals alone, whether via lore or empirical research, is not enough (Thompson et al., 2009; Babcock & Thonus, 2012; McKinney, 2013).

The importance of understanding the writing center from more than just the viewpoint of writing center professionals has been raised by several researchers within the field in recent years. As mentioned earlier, Babcock and Thonus (2012) emphasized the importance of understanding that not all those who use the writing center will interpret it the same way. Likewise, McKinney (2013) cautioned writing center professionals from believing that the writing center is defined the same way by all those who interact with it and deconstructed the writing center community’s “grand narrative” of writing centers as “comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-to-one tutoring on their writing” (p. 3, original italics). Her reasoning was that not all stakeholders who use writing centers would define them in this manner. Similarly, in “Examining Our Lore: A Survey of Students’ and Tutors’ Satisfaction with Writing Center Conferences,” Thompson and her collaborators (2009) questioned writing center lore that has come to be accepted within writing center scholarship. Like McKinney (2013), Thompson et al. (2009) suggested that although some writing center lore is helpful, others need to be discarded in favor of empirical research that is invested in understanding the various “ideas of the writing center” that are held by those who participate in it. Thompson et al. (2009) even asserted that certain aspects of writing center lore, such as students and tutors being peers, are not attainable goals and are therefore “harmful to the students [writing centers] serve” (p. 101). The assertion that writing center lore may need to be discarded or revised in favor of more inclusive and flexible narratives is echoed by Marilee Brooks-Gillies (2018) in “Constellations Across Cultural Rhetorics and Writing Centers.” She argues that these writing center narratives frame the expectations and perceptions of the community surrounding the writing center. Preserving writing center lore that has not been validated by research, and even further has not taken the student perception into account, is a practice that hinders writing centers from fully serving their students.

Writing center scholars have pursued research in various settings in order to gain access to the perceptions of writing center participants. Although students are one of the most important stakeholders of the writing center community, such empirical studies have revolved primarily around tutors’ or writing center professionals’ perceptions of what the writing center is and how it functions. There are remarkably few studies that have invested in understanding students’ ideas of the writing center through empirical research. However, most of these student-centered studies are focused on post-tutorial outcomes via various methods of interpreting “success” within a tutorial session. These interpretations range from fulfillment of session priorities and student satisfaction to tutor-student interactions and relationship.

The disparity between tutor and student perspectives is highlighted within research. In “How Was Your Session at the Writing Center? Pre- and Post-Grade Student Evaluations,” Julie Bauer Morrison and Jean-Paul Nadeau (2003) used surveys in order to ascertain what role grades play in students’ interpretations of success within the writing center. The authors noted that after receiving their grades, the students altered their perceptions of the writing center’s ability to improve their work. While tutors and writing center professionals do not, and should not, place emphasis on grade improvement from a session, students often place grade improvement among their top concerns. Similarly, in “What a Writer Wants: Assessing Fulfillment of Student Goals in Writing Center Tutoring Sessions,” Laurel Raymond and Zarah Quinn (2012) investigated the prioritization of student and tutor concerns within a text. The study used only data collected from tutors’ post-session notes, which means that all data regarding student concerns were interpretations of writing center professionals. However, the results of the study indicate that although tutors and students prioritize concerns differently (e.g., grammar over clarity for students and the reverse for tutors), as long as the students’ concerns were addressed, the sessions were interpreted as successful. The divergence of interpretations of success further supports Babcock and Thonus’ (2012) assertion that perceptions of success within a tutorial will be dependent on participants’ viewpoint and manner of interpretation. The differences between student and tutor priorities and goals illustrate not only that there are issues that need to be addressed with how we tutor students, but also that the writing center has different functions and goals dependent upon the viewpoint of the person defining them.

Through interview analyses with students, tutors, and instructors, Thonus (2001) supplied three differing viewpoints of what role tutors play in sessions. This study specifically pointed out that disparity between student, tutor, and instructor perceptions should be expected as each participant approaches the tutorial session with differing ideas and experiences (Thonus, 2001, p. 77). Thonus asserted that instructors often view tutors as instructional “surrogates.” Although most students do not see their tutors as surrogate instructors, they expect tutors to have more expertise and skill in writing. Thonus’ study showed that students perceive tutors as having a higher level of writing aptitude than themselves, but that students had little understanding of the activities that would take place in a tutorial. In contrast, Thonus’ study showed that the tutors saw themselves as peers of the instructors instead of the students, which meant that the tutors felt that they had even more authority than the students seemed to perceive them to have.

Thonus’ (2001) study had three key implications. First, she illustrated that administrators need to understand the perspectives of stakeholders who directly use and benefit from the writing center, as well as those who are less directly involved, like faculty. Additionally, the study indicated that the interaction of these perceptions plays a part in how success is defined in a tutorial session. For example, a student will think that the tutorial is successful if their tutor demonstrates expertise in writing, but the tutor will find it successful if they feel that the writer has adhered to their advice. Therefore, the same session can simultaneously be successful and unsuccessful depending upon the perceptions of those involved. Finally, this study demonstrated that perceptions of students are less clearly defined than those of tutors or even instructors as to what it is the tutor should do or what role the tutor should play.

It is also important to note that in this study Thonus (2001) distinguished between first-visit and multiple-visit students: “Because only one of the tutees is a first-time client, and because four of the seven tutorials are repeat visits to the same tutor, most tutees are well ahead on the learning curve” (p. 70). Since Thonus’ study had only one first-visit student, no conclusions could be drawn regarding potential differences between first-visit and multiple-visit students. Making the distinction does however highlight a difference in the perceptions of students who have attended the writing center before and those who have never experienced a writing tutorial.

More recently, Cheatle and Bullerjahn (2015) addressed the question of how students perceive the writing center through empirical research in their article “Undergraduate Student Perceptions of the Writing Center.” Instead of focusing on post-tutorial outcomes and satisfaction, this piece focused on the demographic of people that actually use the writing center as opposed to the targeted audience for its services. It also addressed why their students believe that others do not choose to use the writing center’s services. The authors used online multiple-choice surveys and interviews of L1 undergraduate students to answer their questions surrounding students’ perceptions. The researchers found that most students at their university believed that the writing center was for first-year or international students. Additionally, they found that the most prominent opinion of their students about why others do not attend the writing center, is that they “do not feel the need to attend” (p. 24). Although their study aimed to address some of the perceptions of the students at their university, it was not clear how these students were selected nor have all the students who participated in the study used the writing center’s resources. In my own study, I hoped to gather insight into the perceptions of students who do choose to attend the writing center. Additionally, my study included L1 and L2 speakers in order to more accurately represent the diversity of students that attend tutorial sessions at the University of Illinois writing center. Most importantly, I hoped to understand what students perceive the writing center’s goals, practices, and functions to be as opposed to who they believe will make use of its services.

However, these pieces have yet to investigate the “idea of the writing center” looking from the outside in. As writing center scholars have established, or attempted to establish, the insider perspective of writing centers’ functions and goals, we have failed to discover what ideas about the writing center are entering the centers themselves. How students interpret the writing center’s goals and functions, in accordance with Bransford et al. (2000), may affect their learning in the writing center. My study aimed to scratch the surface of student perceptions of the writing center at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Although we cannot know exactly what prior knowledge of the writing center students have before their first visit, gaining some insight into their mindsets will illuminate how we interact with writers and how the perspective of writing center professionals may need to be altered.

Methodology

In order to investigate student perceptions of the writing center’s goals, functions, and practices before and after their first tutorial session, this study utilized three methods of data collection: pre-tutorial questionnaires, post-tutorial interviews, and one interview with an experienced tutor. A pre-tutorial questionnaire was designed in order to gain insight into students’ perceptions before their session. For each question in the questionnaire, students were able to write in their own responses and may have indicated multiple answers for each question. Post-tutorial interviews were used to gather insight as to how the tutorial session may or may not have changed the students’ perceptions of the writing center. An interview with a tutor was conducted as a means of comparing the ways a writing center professional at this center defines its goals, functions, and practices with the ways that students the writing center serves defines its goals, functions, and practices. Since the study took place within the time constraints of a single semester, recruiting student and tutor participants was a challenge. The participants were recruited based on first-visit status and availability to take part in the study.

Study Site

This study took place at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) in the Writers’ Workshop. The writing center has a tutoring staff composed of graduate and undergraduate students. The center fulfills approximately 5500 visits each year. Approximately 75% of the students that utilize the writing center are multilingual. The writing center at UIUC endeavors to help students with their writing skills through interactive and dialogical tutorial sessions with trained tutors and a holistic approach to the writing process. Like other writing centers, its goal is to improve the writer as a whole, instead of just the text, by conducting interactive conversation-based tutorials.

Participants

This IRB-approved study collected data from five first-visit undergraduate students. Choosing first-visit students allowed for me to ascertain and understand students’ pre-tutorial perceptions of the writing center itself. First-visit students were also less likely to have had their own perceptions shaped by the ideas of their tutors or experiences with the writing center. Two participants were female and three were male. Three of the five questionnaires were submitted by students in their first year. One student was a sophomore and one student did not indicate what year of school they were in. All students who filled out questionnaires were later contacted to request interviews and offered $5 gift cards to a local coffee shop in exchange for their time. Two of the students who filled out questionnaires responded.

Interviewed students will be referred to as Mei and Christopher. Both Mei and Christopher were in their first year at the university. Mei was an L2 female health science major while Christopher was an L1 male in the department of general studies.

Data Collection

In order to investigate first-visit student perceptions of the writing center as a whole, this study collected three sources of data: five pre-tutorial questionnaires, two post-tutorial interviews with first-visit students, and one interview with a tutor. The pre- and post-tutorial format allowed the students to offer both their initial perceptions and how those perceptions were or were not changed during their tutorial. The students who participated in this study did not work with the tutor who was interviewed, nor did they work with the same tutor. The tutor who was interviewed did not have access to the questionnaires or interview transcripts and did not interact directly with the student participants. Instead, the purpose of his contribution was to enable me to gather insights into a tutor’s interpretations of student perceptions.

Pre-Tutorial Questionnaires

The questionnaire was designed to gain access to the perceptions of the writing center’s goals and functions from a wide range of first-visit students and where these perceptions were formed.

This questionnaire asked the following questions:

- Please list all of the ways you heard about the Writers’ Workshop (e.g., teacher, friends, adviser, website, etc.).

- What have you heard about the Writers’ Workshop?

- What made you decide to come to the Writers’ Workshop?

- What kind of writing do you plan to work on during your appointment?

- What do you expect will happen during the session?

- What specific concerns do you hope to work on during the session?

This questionnaire also allowed for a larger spectrum of students to describe their perceptions of the writing center. These questions were specifically chosen in order to indicate what the student was looking to accomplish.

Post-Tutorial Interviews

Two brief semi-structured interviews were conducted with first-visit undergraduate students of the writing center. Both of the students who participated in interviews also filled out a questionnaire. Although the questions asked in the interviews varied based on student responses, questions such as the following were used: “How did or didn’t the session meet your expectations?” “Before the session, you said _______. Have your thoughts changed?” These interviews allowed for improved understanding of the information provided in the questionnaire, placed an emphasis on finding out what the students experienced as opposed to what they expected to happen, and provided further depth of understanding of student perceptions entering the tutorial session. They simultaneously offered insight into students’ tutorial experiences in the context of their potentially changed perceptions.

These interviews took place at least a few days after the students’ first tutorials to allow students to absorb the information they gained during their tutorial session. The pre- and post-tutorial approach allowed for the students to offer both their initial perspectives and the changes, if there were any, after the session itself. As students’ schedules were limited, these interviews were twenty minutes or less.

Experienced Tutor Interview

As a means of comparison, one interview was conducted with a tutor. The tutor was a male graduate student in Education with 5 years of experience as a writing center tutor and in his last year at the writing center. He will be referred to as Max. Questions like the following were included: “Do you approach tutoring first-visit students differently?” His views were investigated in order to gather insight into how experienced tutors might interpret student perceptions. An experienced tutor was chosen because his ideas about the writing center’s goals and practices would be more informed by writing center scholarship than a tutor who has spent less time in the writing center. This interview served to elicit the tutor’s sense of the writers’ various perceptions and provided insight into how this tutor understands the students he serves.

Data Analysis

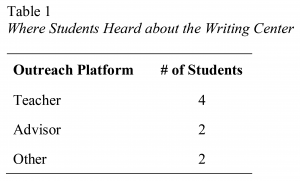

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. In recording these interviews, I hoped to retain the emotions or thought processes that can be lost in simple notes or transcriptions. Transcription of these interviews allowed for in-depth, detailed analyses of student responses and exploration of arising patterns between student responses. Questionnaires were first investigated for arising patterns and then coded with those patterns. For example, in response to “Please list all of the ways you heard about the Writers’ Workshop (e.g., teacher, friends, adviser, website, etc.),” four students wrote “Instructor,” two students wrote “Advisor,” and two indicated other methods of hearing about the writing center. Separate categories for instructors, advisors, and other were created to code the responses.

Interview data was reviewed in order to discover similarities and changes from answers given in the questionnaires.

Results

In this study, questionnaire responses, transcripts of interviews with students, and a transcript of an interview with a tutor were analyzed for patterns of similarity and differences in order to gain insight into the perceptions of first-visit, undergraduate students. In their questionnaire responses, students indicated where they heard about the writing center, what they heard about the writing center, their primary concerns, and expectations. The two interviewed students indicated that they were sent to the writing center by an authoritative figure, neither student expected a dialogical tutorial, and both would return to the writing center for future projects. However, the students’ differing perceptions of the tutorial’s format, revealed that the students’ ideas of how a writing center tutorial would work are particularly unformed. During an interview, the experienced tutor expressed his understanding of first-visit student perceptions, stating that most students do not know what to expect from a tutorial and that he tried to help them to further develop their ability to improve their own writing. Although the students’ and the tutor’s perceptions aligned in many categories, my analysis revealed a disparity between the students’ primary concerns and the tutor’s interpretation of these concerns. The following offers evidence from the data to support these findings.

Questionnaire Responses

Results from the questionnaires were evaluated under four categories: where students hear about the writing center, what students heard about the writing center, students’ primary concerns, and students’ expectations. By separating the results into these four categories it was possible to investigate both from where the five students were forming their perceptions and what the “formed” perceptions were before their first visit.

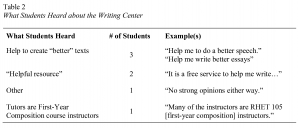

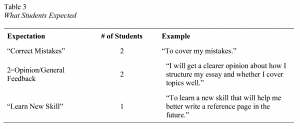

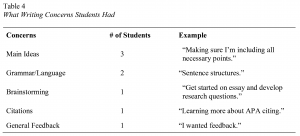

Patterns arising in each category have been illustrated in the tables below. Tables show the number of students that indicated a specific category. Students may have indicated multiple categories for each question. Student responses to the questionnaire were often brief, simply short phrases or incomplete sentences.

All students heard about the writing center from authoritative figures like an instructor or advisor (see Table 1). One student indicated familiarity with the writing center from instructors, but also from the website. Most of the students also indicated that they heard that the writing center placed a focus on helping students create “better” texts (see Table 2). In all but one of the questionnaires, the word “better” was specifically used to describe the text the students were working on. This indicates that these students do not perceive the writing center’s focus to be on their overall improvement as writers, but on the improvement of specific texts. It is interesting to note that there seems to be a strong correlation between the authoritative figures’ suggestions to use the writing center and the use of the word “better” to describe the text-focused services that the students believed the writing center would provide. It seems likely that students have their ideas of the writing center shaped by the authoritative figures that directed them there (Harris, 2010). Therefore, it is important to note that authoritative figures appear to be informing students that the writing center is a place specifically intended for improving specific texts (Rafoth, 2016). The correlation calls for further study on the topic.

All students heard about the writing center from authoritative figures like an instructor or advisor (see Table 1). One student indicated familiarity with the writing center from instructors, but also from the website. Most of the students also indicated that they heard that the writing center placed a focus on helping students create “better” texts (see Table 2). In all but one of the questionnaires, the word “better” was specifically used to describe the text the students were working on. This indicates that these students do not perceive the writing center’s focus to be on their overall improvement as writers, but on the improvement of specific texts. It is interesting to note that there seems to be a strong correlation between the authoritative figures’ suggestions to use the writing center and the use of the word “better” to describe the text-focused services that the students believed the writing center would provide. It seems likely that students have their ideas of the writing center shaped by the authoritative figures that directed them there (Harris, 2010). Therefore, it is important to note that authoritative figures appear to be informing students that the writing center is a place specifically intended for improving specific texts (Rafoth, 2016). The correlation calls for further study on the topic.

Half of the students expected that their tutor would “correct mistakes” in their texts while the other half simply expected to get a second opinion about their writing. Only one student expected to learn a new skill for future writing projects. Although the ways that students expected the session to work varied, students still expected to receive critical feedback, which would alleviate student errors. The students’ focus on critical feedback may demonstrate that students’ perceptions of the writing center lean more towards an editing service/“fix-it shop” (North, 1984) than a resource for writing development (see Table 3).

According to their questionnaires, students indicated that they were most concerned with having the “main ideas” of their papers investigated in the tutorial (see Table 4). Although in previous questions most students stated that they were primarily focused on text improvement, as opposed to learning a new skill, this indicates that they do not particularly perceive the writing center as a place focused solely on sentence-level concerns. The combination of these two goals seems to be at odds, which could indicate student confusion as to the goals and purpose of the writing center. This could also indicate that students do not have or use vocabulary to talk about what they expect and are concerned about. As writing center professionals specialize in writing, they interpret “correct mistakes” and “general feedback” differently. So too with “Main Ideas” and “Grammar.” It would be beneficial to investigate what vocabulary students use to describe their writing concerns and tutorial expectations.

In reviewing students’ questionnaire responses, two important perceptions of the writing center were revealed. First, the students believed that the writing center would help them create “better” texts. As all of the students heard about the writing center from authoritative figures, it would seem that they are deriving this perception from their instructors. This means that these students’ prior-knowledge of the writing center is being shaped by authoritative figures that do not directly participate in writing center services. Second, although the students believed that tutors would “correct” their errors, they also have placed a heavy focus on global-level concerns as opposed to sentence-level. These two key points illustrate the students’ reliance on authoritative encouragement to attend the writing center and their potential confusion about how the writing center works.

Interviewed Students

Both interviewed students were first-year students studying non-writing intensive fields and both went to the writing center at the suggestion of an authoritative figure. Mei came to the writing center because her teacher strongly suggested it for a class essay:

And my teacher told me, to go to this workshop that teaches you how to like write a good essays…

Christopher, however, came into the writing center because his advisor suggested it for his application essay for business school. However, he also specifically mentions asking for help with his writing:

And so, I obviously said like ‘who can I go to refine my essays? What are some good things to do?’ … So they just told me, … ‘the Writers’ Workshop is a great place for your essays to be looked at.’

Although the students were referred to the writing center for different genres of writing and by different authoritative figures, they reported similar experiences. Both reported having limited knowledge of the writing center before arrival. Neither expected a conversational tutorial, but both expressed excitement about the interactive nature of the tutorials and felt the dialogical approach was beneficial to their writing processes. Both described learning tools or skills that would be useful for future writing projects, but neither indicated what they thought these tools were. When asked, both students expressed a desire to return to the writing center to work on future projects. Mei said that after her tutorial she felt “more confident” even though she didn’t have her “errors” fixed for her. When asked what he thought about the approach, Christopher said that he thought “it was a good holistic way to look over an essay” and that “it helped [him] look back at what [he] wrote.” It is important to point out that in addition to these ideas, both students still placed an emphasis on improving the specific texts that they brought in. Mei was concerned with receiving a higher grade on her essay. Christopher was concerned with making sure his application essays were well-written so that he could get into the College of Business at UIUC.

Although the students’ responses during their interviews showed mostly similarities, there was one area in which the students’ ideas diverged. Before their session the students differed in their perception of how a writing center tutorial would work. While Mei expected her tutor to “write my ideas for me,” Christopher expected to turn in the text and get results sent back later. This single relevant area of divergence seems to indicate that students’ perceptions of the writing center are particularly unformed when it comes to the way a tutorial session works.

Tutor Interview

An experienced tutor was invited to participate in an interview to gather information about the understanding of the writing center coming from someone who is an active contributor to its services. It is important to understand the perception of the writing center from those who are immersed in its culture and practices and to see how their beliefs align with prior research on the insider perspective of the writing center.

Max described the writing center’s goal as “helping the writer, not the writing.” He explained that he accomplishes this by helping writers to think of the writing process more “holistically” and giving students “tools to improve their own writing.” By viewing their writing holistically, writers are granted the opportunity to see their writing from a removed position, to see how the global structures, such as organization, argument, etc., of their writing are working. According to Max, it would seem that analyzing the writing process while working on a text in order to discover transferrable techniques and tools is the foundation of writing development.

The tutor interview was also incorporated in order to see how writing center professionals at our center were anticipating the students’ perceptions. It was important to find out if and how the perceptions of both the students that use the writing center’s services and the professionals that provide them were working together, particularly as most prior scholarship has focused on the perspectives of writing center professionals—tutors and directors—without bringing in the student voice. In this study, Max described the perceptions of students in two different ways. First, he explained that students come into their sessions with differing ideas of what the writing center is: “Students come with all kinds of various perceptions about the workshop. One of the most common perceptions is that students think that we’re there to correct grammar.”

Although he said that grammar correction is one of the most common perceptions, he also indicated that the students who come into the writing center often do not have strong opinions or perceptions of the writing center: “Students come in not having any idea of what we do.” This seems an important relationship to highlight. Students are both deeply invested in creating “better” texts and uncertain of how the texts will be improved.

Additionally, when asked if he addressed sessions with first-visit students differently than repeat-visit students, he indicated that he offered the students a brief preview of what to expect from their tutorial session:

So usually, in the first part of the session, like the first five minutes with the new writer I just kind of explain that … what we are going to focus on are large issues. So we’re going to look at structure, organization, … And, yes, we will be looking at individual sentence level issues like grammar if that poses a problem in getting your thoughts across.

He indicated that this preview of how a tutorial session works often helped to alleviate students’ uncertainties about what was happening. Additionally, he shared that this allowed them to make a plan for the session and to map out or prioritize concerns about the text.

Student-Tutor Perception Comparison

In several categories, the students’ perceptions and the tutors’ interpretations of these perceptions matched. Both reported a student focus on “better” texts as opposed to learning new skills that would be applicable to future writing projects. Both indicated that many students come into the writing center after being encouraged to do so by authoritative figures such as professors. Finally, both indicated that students have particularly unformed perceptions of how the tutorial itself will take place. The students do not seem to know how a writing tutorial functions. However, the results from the student interviews and questionnaires reveal a disparity between tutor interpretations of students’ perceptions and what students describe their perceptions to be. While the tutor interpreted students to be focused upon grammar, the students stated that they were looking for help with the main ideas and organization of their texts.

Discussion

Although writing center scholarship has investigated the functions, goals, and practices of the writing center and the perceptions of those involved with it, student perceptions, especially those of first-visit students, have been underrepresented in empirical research. From prior scholarship, we have learned the following: students believe that tutors should have some authority and expertise (Thonus, 2001), students perceive that the writing center is for first-year and international students and that is why others do not choose to utilize its services (Cheatle & Bullerjahn, 2015), and students’ interpretations of success range from grade improvement to session-control. However, we do not know the information or expectations that students are bringing with them into the writing center (Morrison & Nadeau, 2003; Raymond & Quinn, 2012; Thompson et al., 2009). According to Bransford et al. (2000), this prior knowledge plays a key role in what students understand about their learning environment, their learning process, and the information they take in. However, in previous scholarship the students’ prior knowledge of the writing center and its practices as well as where they derive these perceptions from has been unclear. I discovered that many students who enter the writing center have little idea of how their session will take place and are also focused upon creating a “better” text. Additionally, the study uncovered that most of these students were directed to the writing center by an authoritative figure such as a professor or an advisor.

Although this study indicates interesting relationships between students’ prior-knowledge and authoritative figures, as well as a disparity between student and tutor interpretations of priorities, it is limited by its small sample size. It would be beneficial to replicate this study in order to further gain insight into the students’ prior knowledge of the writing center and the students’ writing concerns. Additionally, the experience of students in the context of a writing center at a doctoral-granting, research university like this one may be different from those at other writing centers. The writing center at the University of Illinois also has a large population of multilingual writers which further differentiates it from writing centers elsewhere. Therefore, these results may not be applicable in other writing centers. However, the methodology is easily replicable in order to discern the perceptions of students or writers at writing centers in other contexts. The questionnaire could also be used on a larger scale to gather a more representative image of the students that individual writing centers serve.

Still, this study offers insight into the role of prior knowledge within the writing center context. Taking the prior knowledge of its students into account could greatly benefit writing centers by allowing tutors to better negotiate how to interact with those who use its services.

The results from this study indicated that, although students’ prior knowledge of the writing center influences their expectations of the session, it may not affect their satisfaction with the tutorial or their likelihood to return. The interviewed students indicated that they had very little idea how the session would be conducted, but, after completing their sessions, they were excited about the conversational approach that the tutorial took. Although, after the tutorial Mei and Christopher felt that they had learned skills which could be used in the future, both students still placed emphasis on text-focused goals, such as receiving a higher grade on the essay.

Understanding students’ prior knowledge of the writing center as a place that will help them achieve a “better” text is important to the way that a tutor approaches a session with a writer (Bransford et al., 2000). While the writing center has empirical research and lore upon which it can rely to define itself, students seem to have remarkably little to use for understanding the “idea of the writing center” (North, 1984), and the current outreach methods used by writing centers are not adequately conveying a description of our goals and services (Harris, 2010). Most of the students in this study only know the writing center through what they have been told by authoritative figures outside of the writing center. These students seem to be relying almost entirely upon the perspective of those who are not active participants of the writing center in order to understand what it is that the writing center does and how. The importance of how we introduce the writing center and its goals, practices, and functions to our communities, especially to the writers who utilize its services, may impact how students prepare for their tutorials (Harris, 2010, p. 69). This prompts the question of how writing center professionals can change their outreach practices in order to improve the broad understanding of what the writing center does and how it functions.

Currently at the University of Illinois Writers Workshop, like many other writing centers, the following outreach methods are in use: in-person appearances at campus resource fairs, new student and teacher orientations, and individual class visits upon request; a well-maintained and easy-to-find website; and marketing of services through events, advising listservs, and social media. Although these methods are effective in making students and faculty aware of our center, they do not necessarily show how our sessions will function or the goals and practices of the writing center. The confusion surrounding the way a tutorial session functions indicates that writing center professionals need to devise new methods of outreach on campus. How can writing centers improve students’ (and faculty’s) understanding of the writing center and its mission through outreach?

In order to alleviate some of the confusion surrounding the way a tutorial works, this writing center is creating a video to simulate the dialogical nature of our tutorial sessions. The video will be comprised of writing center staff demonstrating a tutorial so that students and faculty may see a tutorial in action. Using a video in this manner could easily be done at other universities in orientations, class visits, or shared on the writing center’s website and social media platforms. In fact, it is a practice that many other writing centers are utilizing in their own outreach methods.

As most students who came into the writing center with expectations of having their tutor “correct mistakes” were directed there by an authoritative figure, it is important to further investigate the perceptions of these figures, such as professors and advisors. It seems clear that the first way of improving outreach to authoritative figures at our university is finding a means of opening a dialogue with instructors, advisors, and other authoritative figures regarding how the writing center functions and what its goals are. In their article, Cheatle and Bullerjahn (2015) come to the same conclusion, stating that faculty outreach will be a “key aspect of future development” (p. 25). Improving faculty outreach methods could serve to help alleviate disparities between how writing center professionals define the center and the definition used by authoritative figures on campus. At large universities like this one, where there are thousands of faculty, teaching assistants, and non-tenure track instructors across campus, it may be difficult to implement. Talking at new faculty and TA orientations is a step in the right direction, but many writing centers at large research universities like this one are still exploring how best to engage with faculty and establish ongoing relationships.

Additionally, tutors at other writing centers may also be able to get involved in the assessment of students’ perceptions by experimenting with different strategies for tutoring first-visit students. When beginning sessions with first-visit students, writing center tutors often ask if the student has been to the writing center prior to that appointment. Often this question is used as a means of building rapport, rather than using it as an opportunity to open a dialogue with the writer about their prior knowledge of writing center practices. This question gives tutors an opportunity to help their students anticipate how their session will work and to show students what types of concerns the writing center prioritizes. William J. Macauley (2005) briefly noted the same strategy in “Setting the Agenda for the Next Thirty Minutes,” stating that when forming a plan for the session with a first-visit student, discussing the writing center’s goals as well as the goals for the session is useful. I would argue further that it can also be used as an opportunity to invite students to discuss their writing practices as well as their ability to verbalize their writing concerns and tutorial expectations. As Max described, using the question as an opportunity to not only describe our version of the writing center, but also to open a dialogue about their writing could be beneficial to both the tutor and the student. According to Bransford et al. (2000) “There is a good deal of evidence that learning is enhanced when [educators] pay attention to the knowledge and beliefs that learners bring to a learning task, use this knowledge as a starting point for new instruction, and monitor students’ changing conceptions as instruction proceeds” (p. 11). Therefore, I argue that this practice should be more widely adopted because this question can be used as a platform for understanding the prior knowledge that students bring with them to their first tutorial and additionally, it could potentially even be used to help students discover the necessary vocabulary for conveying their concerns and ideas.

Students and tutors hold divergent expectations of the writing center. It is clear that students expect their tutors to have expertise in their field (Thonus, 2001) and that students want their tutor to point out places where their writing could be improved. Whether their focus is on “correcting mistakes” as Max indicates, or on “general feedback” as the students do, they want their tutor to improve their texts. Although the students had little idea of the goals of the writing center beforehand, after their first session, students’ perceptions seem to be more aligned with the writing center’s actual goals. Students in this study indicated that they were primarily concerned with main ideas, but Max indicated that most students come to him requesting help with grammar. Although grammar was another issue that many students indicated as important, their focus on global issues was one that needs to be researched further.

Conclusions

In this study, I set out to discover what undergraduate first-visit students’ perceptions of the writing center and its goals are and where these perceptions were formed. From this study, it was clear that students enter their tutorial sessions with various forms of prior knowledge of the writing center itself, but most also indicate uncertainty about how it accomplishes its goals. These students seem to see the writing center as a service focused on creating “better” texts as opposed to a place focused on skill development and long-term improvement. However, the interviewed students also expressed excitement about the writing center’s interactive approach. Students realize once they have experienced the “holistic” approach to writing center tutorials, that this is what they needed in order to not only improve their texts, but also to learn new skills to be used in future writing projects.

More research into this division of perceptions would further highlight the differences between the ways the writing center scholarship frames the writing center’s goals, and how students who use the writing center may interpret them (McKinney, 2013; Harris, 2010). Addressing this gap in understanding will allow writing centers to become more efficient and better able to serve those who utilize its services. The results of this study indicate that writing center scholarship should continue to pursue the following questions: What do advisors and professors know/understand about the writing center’s goals and functions? How/Do tutors’ practices differ with first-visit students as opposed to return-visit students? How do tutors address students’ writing habits by accessing their prior-knowledge about writing and revision techniques? What vocabulary do students use/have to describe their writing concerns and tutorial expectations? Additional research is necessary in order to further develop the store of empirical research on students within writing center scholarship.

References

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center: Towards an evidence based practice. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Bransford, JD., A. L. Brown, & R. R. Cocking, editors. (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Brooks-Gillies, M. (2018) Constellations across cultural rhetorics and writing centers. The Peer Review, 2(1).

Cheatle, J., & Bullerjahn, M. (2015). Undergraduate student perceptions and the writing center. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 40(1-2), 19-27.

Harris, M. (2010) Making our institutional discourse sticky: suggestions for effective rhetoric. The Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 47-71

Macauley, W. J. (2005). Setting the Agenda for the Next Thirty Minutes. In B. Rafoth (Ed.), A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One, 1-8. Portsmouth, NH: Boyton/Cook Pub.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Morrison, J. B., & Nadeau, J. P. (2003). How Was Your Session at the Writing Center? Pre-and Post-Grade Student Evaluations. Writing Center Journal, 23(2), 25-42.

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446.

Rafoth, B. (2016) Faces, factories, and Warhols: a r(evolutionary) future for writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 17-30

Raymond, L., & Quinn, Z. (2012). What a writer wants: Assessing fulfillment of student goals in writing center tutoring sessions. The Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 64-77.

Thompson, I. (2006). Writing center assessment: Why and a little how. The Writing Center Journal, 26(1), 33-61.

Thompson, I., Whyte, A., Shannon, D., Muse, A., Miller, K., Chappell, M., & Whigham, A. (2009). Examining our lore: A survey of students’ and tutors’ satisfaction with writing center conferences. The Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 78-105.

Thonus, T. (2001). Triangulation in the Writing Center: Tutor, Tutee, and Instructor Perceptions of the Tutor’s Role. The Writing Center Journal, 22(1), 59-82.