Matthew Fledderjohann, Le Moyne College

Emily Perkins, Le Moyne College

For decades, writing centers have been helping students navigate the complexities of rhetorical expectations, guiding their learning, and assisting as they become better writers who can develop better pieces of writing (Salazar, 2021). But, with the arrival of generative AI (GAI), students’ learning experiences in connection to writing are rapidly changing. The broad reality of this shift is obvious, but its exact nature is still being explored, and the influence of GAI on writing centers’ pedagogical practices are uncertain.

As writing center directors, we are particularly interested in what students’ use of and their attitudes toward GAI suggest about the writing center’s role in helping students learn and faculty members grow. How do students’ experiences with GAI and their perceptions of these tools influence the role and position of writing centers at contemporary college campuses? To explore these issues, we conducted an IRB-approved study, through which we surveyed 357 students enrolled at the small, liberal arts college where we work to learn about their experiences with GAI and their thoughts regarding this technology.

Through this research, we’ve discovered that many students believe one of the key changes this technology has initiated is to make writing less challenging. We heard this sentiment from a junior studying marketing who used ChatGPT and Grammarly to, among other tasks, draft an assignment that he revised. He shared that he believes GAI is “a tool to work alongside us and make [our] life easier.” Another student, a sophomore majoring in psychology who has used GAI to help her with her academic work, described GAI as “[a] way to make it easier for students, but sometimes to[o] easy.” This “too easy” admission points to the uncertainty some students have about GAI’s capacity to change learning by simplifying writing processes. Not all students are convinced this increased ease is a good thing. A sophomore risk management major who reported never having used GAI on his academic assignments leveled strong criticism against these tools. He said GAI is “shortsighted” and clarified that it “hinders the growth of those using it. Skills that would have been developed through the process of brainstorming and structuring arguments now have artificially synthesized solutions. You aren’t growing or learning by using AI to fill in the gaps of your weaknesses, and those who take the easy way out are doing themselves a great disservice.” As these students’ insights suggest, perhaps GAI makes doing the work of learning and writing easier, more streamlined, and less complex, but does it make learning better? And isn’t struggling through unknowns central to a meaningful learning experience?

In what follows, we present detailed information about who is using and not using GAI, how and why they’re using it, and the extent to which this use is influential in helping writers resolve the inherent ambiguities of learning and writing in academia. We find that writers are using GAI to mitigate what organizational management scholars call “knowledge ambiguity” (Van Wijk et al., 2008) and what sociologists call “pervasive ambiguity” (Ball-Rokeach, 1973). However, we find that writers are also wrestling with uncertainty about the tools themselves. This points to a third kind of ambiguity—what we call “process ambiguity”—which we believe writing center tutors and administrators are particularly well positioned to respond to. As we continue into this new compositional future, we anticipate that tutors will be asked to collaborate with writers and GAI to negotiate the ambiguities incurred by content, connections, and rhetorical situations. We believe that writing centers are best positioned to help writers develop as thinkers as they work through not just what to write but how to write. We believe that writing centers can also help instructors advance as pedagogues who thoughtfully respond to GAI’s disruptions. As GAI alters the way writing happens and its role in advancing learning, writing centers need to use what we know about students’ GAI use and perceptions to guide our tutor training, influence our cross-campus collaborations, and inform our response.

Literature Review

As a mediating, knowledge-making, social and rhetorical activity (Adler-Kassner & Wardle, 2016), writing requires sustained engagement with uncertainty and ambiguity. Words evoke different responses from different people. Meanings shift across contexts. Writing instructors know this and have leveraged students’ interactions with ambiguity to help students learn. Writing instructors have recognized the role of ambiguity in teaching first-year writing (McIntyre, 2018), critical reading (Sullivan, 2019), and creative writing (Cosgrove, 2008). We encourage our students to engage with writing’s ambiguities as practice for navigating reality’s uncertainties. Even beyond the compositional context, the verdict is clear: ambiguity can open rich, compelling possibilities for what and how we learn (Nikolaides, 2015; Suzawa, 2013).

While engaging with ambiguity can advance learning, it can also be really difficult. To that end, in the context of writing center practice, tutors have been particularly well situated to help students learn as they are confronted with two different kinds of ambiguity—knowledge ambiguity and pervasive ambiguity. Knowledge ambiguity is a concept used in organizational management to describe “the inherent and irreducible uncertainty as to precisely what the underlying knowledge components are and how they interact” (Van Wijk et al., 2008, p. 833). In essence, this is ambiguity that emerges when what is known and/or how knowledge elements connect are unclear. Pervasive ambiguity is a psychological concept defined as the inability to “establish meaningful relational links” within one’s environment, making a social situation undefinable (Ball-Rokeach, 1973, p. 379). Uncertain connections are central to both knowledge ambiguity and pervasive ambiguity; however, in rhetorical terms, it is elements of the message that are unclear in knowledge ambiguity, whereas uncertainty about the rhetorical situation is what drives pervasive ambiguity.

Writers must work despite and through both kinds of ambiguity to learn and develop clear arguments, and writing center tutors have consistently been influential in helping writers locate this knowledge (Harris, 1988), make these connections (Mackiewicz & Payton, 2022), and gain clarity about these situations (Kirsch, 1988; Raign, 2017). Yet, the work of helping writers negotiate ambiguity and expand their critical thinking skills as they wrestle with uncertainties has drastically shifted with the arrival of GAI. The expansive capacities of large language models (LLMs) means that writers have easy access to tools that can generate complex ideas for them, explain uncertain concepts, synthesize information by putting it in conversation with other data, and tailor text for a range of audiences and purposes. In a business blog post, Choudhary (2024) asserts that GAI can clear the “Ambiguity Fog” by “providing multiple perspectives and interpretations” to help resolve uncertainty. With just one ask and a click, tools like ChatGPT can identify patterns and relationships, make inferences about the meaning of signifiers, and seemingly eradicate writers’ uncertain struggle to think and compose. Given these seismic changes in how students can write, what is the role of ambiguity in compositional instruction and writing center interactions? How is GAI being used to resolve knowledge ambiguity and pervasive ambiguity, and what does that mean for writing centers?

Methodology

Only a few studies are able to shed light on students’ awareness of, use of, and confidence in GAI tools (Amoozadeh et. al, 2023; Barrett & Pack, 2023; Kelly et. al, 2023; Smolansky et. al, 2023). Therefore, we determined it would be valuable to start exploring these questions by broadly unpacking how GAI is influencing students’ learning experiences and what students themselves think about these tools. To that end, we designed an IRB-approved study (IRB2023-42A) to anonymously survey currently matriculated undergraduate and graduate students at the small, Jesuit college in the Northeastern United States where we work as writing center directors. We chose this methodology so we could access a wide range of student experiences and perceptions efficiently and effectively. The survey’s design also allowed us to maintain research participant confidentiality, thereby creating a safe environment for participants to answer openly and honestly questions about their behaviors with and attitudes towards GAI without fear of retribution.

Survey Questions

The online survey included multiple choice, check-all, and short answer questions that covered demographics and participants’ usage and attitudes towards GAI. We elicited feedback about who the respondents were, whether they have or have not used GAI for their academic work, what GAI tools they have engaged with, what kinds of academic assignments they have used those tools for, as well as how and why they used them. We also asked participants to share to the best of their knowledge how their peers engage with and feel about GAI. Additionally, the survey contained 5-point Likert scale questions that obtained feedback on participants’ experience using GAI in the classroom, views on GAI in relationship to academic integrity, and overall perceptions on how GAI tools may influence their future careers. The survey script is included in Appendix A.

Recruitment

In efforts to gather data from a wide range of students across our campus, we distributed the survey multiple ways. We sent out a call through the campus’s digital newsletter, hung posters with the QR code on bulletin boards across campus, and encouraged instructors to promote and distribute the virtual survey in their classrooms.

Participants

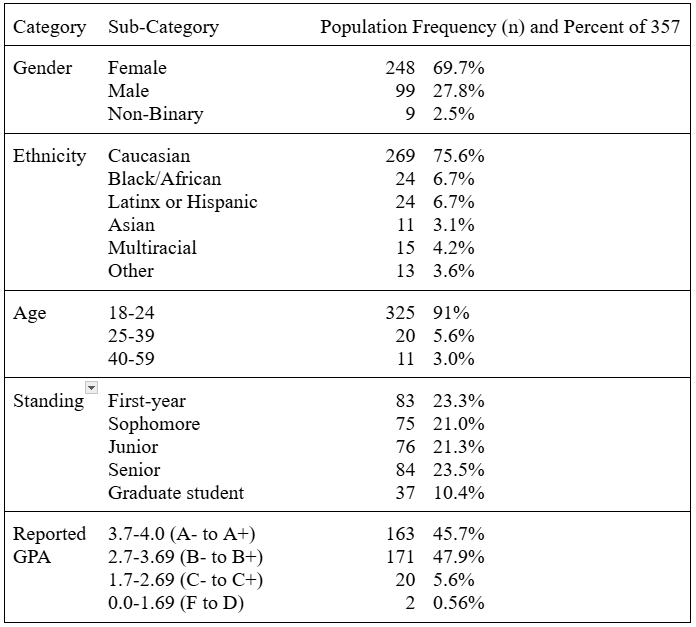

Table 1 provides survey participant demographic information. All survey questions were optional, so the totals for each category do not necessarily add up to the total number of participants. Participants had to be at least 18 years old and currently enrolled at our institution. Undergraduate and graduate populations from across all disciplines and demographic backgrounds were contacted. Incentives for participation were not given. We compared our results against publicly available data about our college’s enrolled student population’s gender and ethnicity distributions to learn that we obtained a representative sample of our institution with these 357 survey responses.

Table 1

An Overview of Participant Demographics

Quantitative Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics and compared distributions, correlations, and means to identify connections between factors relating to students’ use of and attitudes towards GAI.

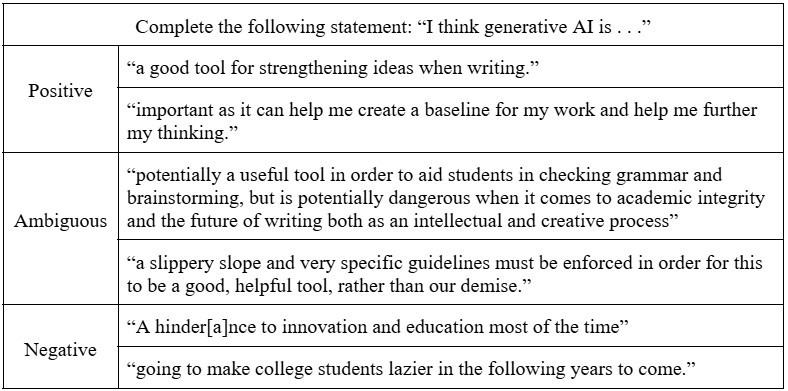

Qualitative Data Analysis

To gather contextual insights and meaningful insights that clarify the quantitative information, we worked through the responses to the question that asked students to complete the phrase “I think GAI is . . .” We systematically identified which responses were “positive,” “ambiguous,” and “negative.” For reliability, we first independently coded participants’ responses. Then, we discussed any discrepancies before assigning a final code. These conversations allowed us to establish a baseline for how we were defining what constituted a “positive,” “ambiguous,” or “negative” response and ensure that our values coding approach reflected the contents of the text rather than our ideas as coders. Examples of the kinds of comments that were organized within these categories are included in Appendix B.

Results

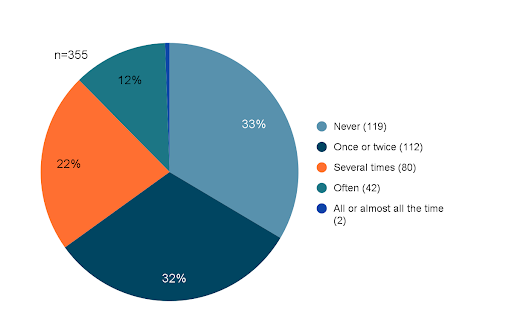

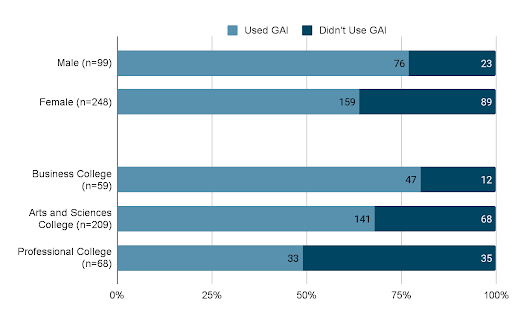

One of the first questions survey respondents encountered simply asked them to identify the frequency with which they have used GAI for their academic work. As detailed in Figure 1, 33.5% (n=119) of respondents said they have never used this technology in connection to their academic responsibilities. The next highest response category was the 31.5% (n=112) of respondents who said they’ve used GAI “once or twice.” Progressively, fewer respondents said they had used GAI “several times” and “often,” and less than 1% (n=2) reported using this technology “all or almost all the time.” GAI users were most likely to identify as male than female as 76.7% (n=76) of all male respondents (n=99) and 64.1% (n=159) of all female respondents (n=248) reported using GAI at least once. Additionally, GAI users were more likely to be enrolled in our college’s business college as 79.7% (n=47) of the respondents seeking business degrees (n=59) reported using GAI. In contrast, 67.5% (n=141) of the respondents who were seeking degrees from our college of arts and sciences (n=209) and 48.5% (n=33) who were seeking a professional degree (in healthcare or education) (n=68) reported using GAI at least once. These rates of GAI across gender and school are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Have You Used GAI for Academic Work?

Figure 2

GAI Use Across Gender and School

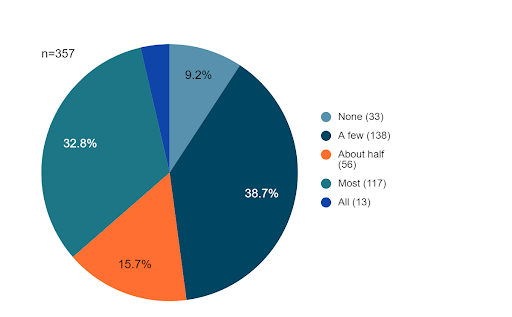

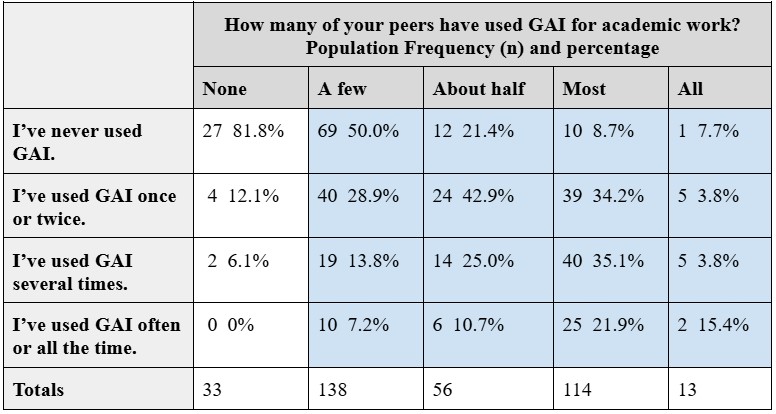

Interestingly, while a third of participants said they hadn’t used GAI for academic purposes, only 9.2% (n=33) thought their peers hadn’t been using GAI either (Figure 3). A slight majority of respondents (52.1%, n=186) said that about half, most, or all of their peers had been using GAI for their course work. Notably, as indicated in Table 2, respondents’ perceptions of their peers’ GAI usage was significantly related to their own GAI usage, X2(9, 321) =52.38, P=<.00001 [1]. Respondents who had used GAI less frequently were more likely to say that none of their peers had used it either, and respondents who had used GAI more frequently were more likely to say that more of their peers had been using it.

Figure 3

Have Your Peers Used GAI for Academic Work?

Table 2

Comparison of Respondents’ Perceptions of Peers’ GAI Usage to Their Usage

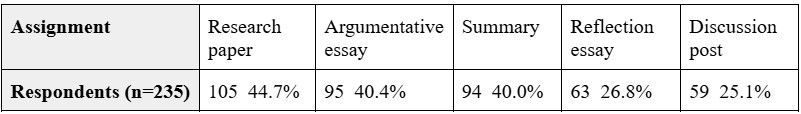

Later in the survey, we asked the 235 respondents who said they’d used GAI at least once to tell us more about the kinds of assignments they’ve used GAI for. Respondents selected from a list of 15 common academic genres (plus “other”). The five most frequently selected genres are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

What Kinds of Academic Assignments Have You Used GAI On? (Top 5 Results)

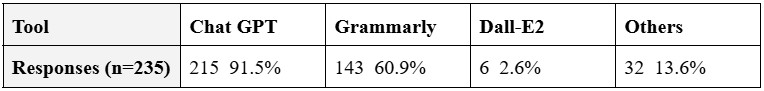

In regard to what GAI tools students are using, the most popular software, by far, was ChatGPT with 92% of the respondents who reported using GAI at least once saying that they’d used this resource. As shown in Table 4, the next most used program was Grammarly—a tool about which one respondent shared in response to a short answer question, “I didn’t realize at the beginning of this survey that Grammarly is considered AI.” Other GAI tools used included Claude, Copilot, Snapchat’s My AI, and huxli.ai [2].

Table 4

What GAI Tools Have You Used for Academic Work?

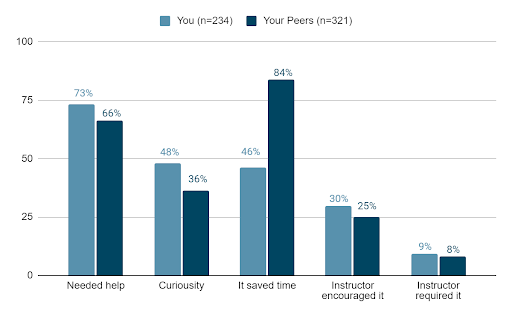

We asked respondents who had used GAI to identify the various reasons for this use, and we similarly asked respondents who said their peers had used GAI to identify what they believe motivated their peers’ usage (Figure 4). Whereas most GAI users self-identified as being motivated by needing additional help (73%, n=171), respondents believed that their peers were most likely to be using GAI in order to save time (84%, n=269). Across these five categories of motivation, the most notable response discrepancy was between respondents’ who self-identified as using GAI to save time (46%, n=108) and the aforementioned category of respondents who believed their peers had used it to save time. Response rates were most similar for whether they or their peers had been encouraged or required to use GAI for academic assignments.

Figure 4

Why Have You and Your Peers Used GAI for Academic Work?

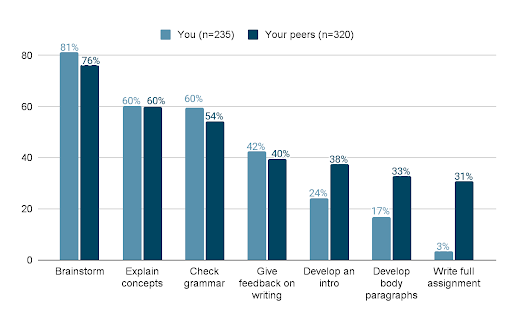

Another question asked GAI-using respondents to detail how they’ve used GAI. A parallel question later asked respondents who said they know peers who have used GAI to identify how these peers have been using it. The results for the top seven ways students reported using GAI corresponded with the top seven ways students believed their peers have used GAI (Figure 5). For both the students’ usage and what they speculated about their peers’ usage, brainstorming was the most frequently identified GAI use, followed by explaining concepts, checking grammar, and providing feedback on writing. Notably, while only 3.4% (n=8) students self-identified as having used GAI to write full assignments, 30.9% (n=99) believed that their peers have used GAI to write full assignments.

Figure 5

How Have You and Your Peers Used GAI for Academic Work?

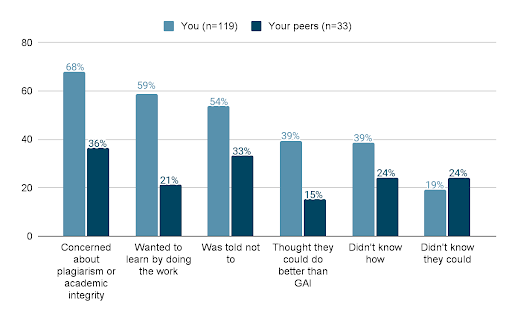

In addition to what respondents said about what has motivated GAI use and which applications of this technology are most popular, respondents provided insight into what is deterring some of them or their peers from using GAI. We asked the 119 respondents who said they hadn’t used GAI for academic work and the 33 respondents who said they didn’t know peers who have used it about why they or, to the best of their knowledge, their peers have stayed away from this technology (Figure 6). The most commonly selected motivation for avoiding GAI had to do with apprehension about plagiarism or academic integrity; 68.1% (n=81) of the respondents who hadn’t used GAI themselves said they hadn’t wanted to risk being accused of plagiarism, and 36% (n=12) of the respondents who didn’t know any peers who have used GAI said their peers were similarly dissuaded by the possibility that GAI use could raise academic honesty concerns. While many of the categories of response differed considerably between how respondents answered for themselves and what they speculated regarding their peers’ non-GA usage, the largest discrepancy was apparent between the 58.8% (n=70) respondents who said they were personally motivated to not use GAI because they wanted to learn by doing the work themselves and the 21.2% (n=7) respondents who believed that this kind of intrinsic drive to learn motivated their peers not to use GAI.

Figure 6

Why Haven’t You and Your Peers Used GAI for Academic Work?

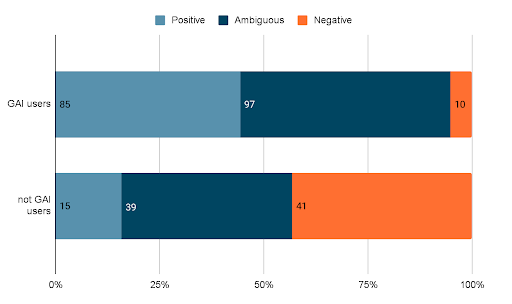

As previously mentioned, to analyze the responses to that open-ended question that asked students to complete the phrase, “I think generative AI is . . .”, we organized them by assigning responses a value code of “positive,” “ambiguous,” or “negative.” Recognizing that “beliefs are embedded in the values attached to them” (Wolcott, 1999, p. 97) and can be considered “rules for action” (Stern & Porr, 2011, p. 28), we used this coding method to explore students’ personal knowledge, experiences, and opinions with and about GAI. Furthermore, we used this information to determine whether there was a significant connection between students’ perceptions of these tools and their engagement with them. After locating which free-text responses suggested “positive,” “negative,” or “ambiguous” attitudes about GAI (n=289), we identified which respondents indicated that they had used GAI tools at least once for academic purposes (n=192) and which respondents reported not having used GAI for academic purposes (n=97). Results from this analysis are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Respondents’ Attitudes Towards GAI

As the data show, there was statistical significance when looking at students’ perception of the tools and engagement, X2(2, 289)=67.5056, P=<.00001. Students who had engaged with the tools at least once were more likely to have positive feelings about them. A few of these positive responses included descriptions of GAI as: “a helpful tool to understand and develop concepts,” “great for college students that need the extra help in their assignments,” and “an extremely powerful tool that should be used to complement or enhance one’s own work.” Many of these students used words like “useful” or “helpful” to describe their beliefs about the benefits and capabilities of GAI. In contrast, those who felt negative about GAI used words like “dangerous” and “easily abused” when sharing their concerns about these new and powerful tools. This group of students feared GAI tools are a “hindrance to innovation,” affecting both the intellectual and creative process (see Appendix B for additional examples of respondents’ perspectives about GAI).

In addition to many students feeling distinctly positive or negative about GAI, many students, both GAI users and non-users, felt ambiguous about GAI. Many of these students referenced the potential problems with GAI, including its capacity to blur ethical lines and be misused, but in the same breath, they acknowledged potential benefits if the tools were “used correctly.” In fact, across these 136 instances of respondents identifying ambiguity regarding the value and use of GAI, the phrases “but,” “but also,” or “however” were used in 64 responses to establish a direct contrast between the perceived values and detriments of this technology.

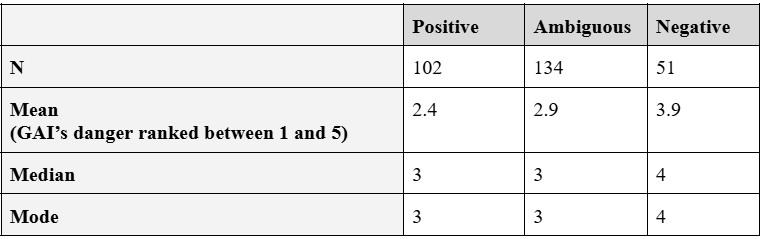

We further analyzed respondents’ attitudes towards GAI by comparing these short-answer responses to an earlier question that asked them to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with this phrase, “GAI is dangerous” on a Likert scale between 1 (“strongly disagree”) and 5 (“strongly agree”) [3]. We cross-referenced the numerical responses to this question about GAI’s dangerousness against whether each respondent’s attitude toward GAI had been coded as “positive,” “ambiguous,” or “negative.” We performed a Kruskal-Wallis test on the Likert scale responses for these three groups. The differences between the rank means for each category of 2.4 (positive), 2.9 (ambiguous), and 3.9 (negative) were statistically significant, H (2, n=287)=51.7896, P=.00001. Additional information about this is presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Comparison of Respondents’ Ranking of GAI’s Dangerousness with Their Short-Answer Views of GAI

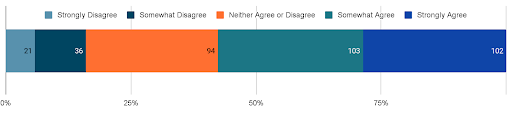

Another Likert scale question asked the respondents to rank their response to this statement: “Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT can provide me with unique insights and perspectives that I may not have thought of myself.” In correspondence with the results of the analysis comparing the “negative,” “ambiguous,” and “positive” attitudes, we found that 57 respondents strongly disagreed or somewhat disagreed with GAI’s insightfulness, 94 neither agreed nor disagreed, and 205 somewhat agreed or strongly agreed (Figure 8). Notably, 85.7% (n=18) of the 21 respondents who strongly disagreed that GAI can be insightful had never used GAI for academic purposes. Additionally, only 1 of the 102 respondents who strongly agreed that GAI could provide insightful perspectives later described it as negative in his short answer responses. Also, of the 172 respondents who strongly agreed or somewhat agreed with this statement and reported using GAI at least once, 86.0% (n=148) said they’d used GAI to help them brainstorm.

Figure 8

“GAI Can Provide Me with Unique Insights and Perspectives that I May Not Have Thought of Myself”

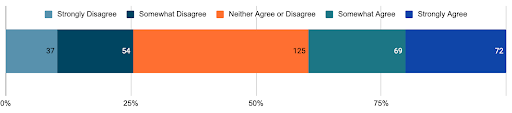

The final set of results we’ll consider are those having to do with respondents’ experiences with and perceptions about the kind of instruction they’ve received about GAI and the institutional responses to GAI. The survey included another Likert scale question asking them to rank the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “I have received instruction about how to use GAI from [our institution’s] faculty or staff.” As Figure 9 presents, a full 58.0% (n=206) of respondents strongly or somewhat disagreed with this statement, and only 26.2% (n=93) somewhat or strongly agreed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, only 15.1% (n=14) of the 93 respondents who agreed with this statement reported never having used GAI for their academic work.

Figure 9

“I Have Received Instruction About How to Use GAI From [Our Institution’s] Faculty or Staff”

![Chart illustrating responses to "I have received instruction about how to use GAI from [our institution's] faculty or staff": Strongly disagree to Strongly Agree. Strongly disagree (137), Somewhat disagree (69), Neither agree or disagree (56), Somewhat agree (53), Strongly agree (40).](http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Figure-9.png)

Figures 10, 11, and 12 present participants’ responses to questions about faculty integration of GAI tools into their teaching practices, restrictions on GAI, and GAI use in connection to academic integrity standards. Across all three questions, the most frequently selected response was the uncertain “neither agree or disagree”; 35.0% (n=125) of the respondents to the statement about faculty integration of GAI tools in the curriculum (n=357) weren’t sure if they agreed or disagreed. Similarly, 32.5% (n=116) of the respondents to the statement about not restricting GAI for coursework (n=357) didn’t know what they thought, and 33.2% (n=118) of the respondents to the statement about GAI’s violation of academic integrity policies (n=355) couldn’t agree or disagree. In fact, of the 355 students who responded to all three of these questions, 64.2% (n=228) of them said they neither agreed or disagreed with at least one of these statements.

Figure 10

“Faculty Should Make an Effort to Integrate the Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Their Curriculum”

Figure 11

Students Should Not Be Restricted From Using AI for Coursework

Figure 12

“Use of AI Text Generation Tools to Complete Coursework Violates Integrity Policies at [Our Institution]”

![Chart illustrating responses to "Use of AI text generation tools to complete coursework violates integrity policies at [our institution]": Strongly disagree to Strongly Agree. Strongly disagree (26), Somewhat disagree (58), Neither agree or disagree (118), Somewhat agree (86), Strongly agree (67).](http://thepeerreview-iwca.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Figure-12.png)

Discussion

As has been made apparent across the previous results section, 357 responses to a survey asking about students’ use of and opinions about GAI generates a wealth of data. Broadly, this data show us that male students are more likely to report using GAI than female students, that there is a notable population of students who report not using GAI on their academic work, that students think more of their peers are using GAI than they are, that many report being motivated by needing additional help but believe their peers are using GAI to save time, that students are using GAI for a wide range of assignments, that brainstorming tops the list for reasons why these respondents use GAI, and that many students aren’t sure if GAI is a good thing or a bad thing or the extent to which it should be incorporated into their learning or influence expectations of academic integrity. There is much that could be said further about all of these issues. However, even though we did not ask participants about their broader perceptions of writing or their possible writing center experiences, we find that these students’ engagement with ambiguity, in particular, carry implications for how writing centers can serve the needs of students and faculty members working through GAI’s benefits and challenges and its implications for their learning.

Addressing Knowledge Ambiguity

In regards to ambiguity, we see evidence that respondents are consistently using GAI to resolve the uncertainties arising from knowledge ambiguity. GAI is making these aspects of learning easier. In their work on knowledge ambiguity, Van Wijk et al. (2008) identify this uncertainty as a sometimes positive force—a way for organizations to retain proprietary information since the sources and components of that knowledge are not easily accessible to an outsider. But this benefit for organizations is part of what makes learning so difficult for students since students are inherently outsiders, novices to the disciplines they are studying. And, as evidenced by the number of respondents who said they or their peers had used GAI to save time, students are sensitive to the reality that, “[e]xplaining and learning the specifics of the knowledge source takes time” (Van Wijk et al., 2008, p. 833). We see students working to alleviate their struggle with knowledge ambiguity through their consistent use of GAI to explain concepts. After brainstorming, explaining concepts was the second most frequently selected reason why respondents used GAI for their academic work and speculated reason why their peers had been using GAI (see Figure 5); 60.4% (n=141) of the 235 GAI users who answered this question said explaining concepts was one of the reasons why they’d turned to GAI, and 60.0% (n=192) of the 320 respondents who answered this question about their peers cited explaining concepts as one of the reasons their peers had been using GAI. And many of them understand this to be a good thing. A nursing student who had used ChatGPT and Grammarly several times to help with some summary assignments said, “It can help explain a concept I don’t understand in a way that allows me to comprehend it and learn from it.” Another respondent, a first year student majoring in finance who reported using GAI to brainstorm, explain concepts, provide feedback, develop an introduction, and check grammar said that GAI is beneficial “to help write about something you don’t fully understand.”

Of course, while students may be increasingly willing to use GAI to resolve knowledge ambiguity, writing centers should continue positioning themselves as resources that can help writers respond to this difficulty. This is a role we’re already very familiar with. We know that while generalist tutors will never have all requisite content knowledge, they can still productively help writers through their position as what Hall (2017) has termed “expert novices” (p. 54). Tutors can show students how to learn through and despite students’ knowledge ambiguity, which is something that GAI cannot do—transition from dispensing new information to showing how to find, evaluate, comprehend, and connect that information. The varied, personalized value that tutors provide in this regard reminds us that GAI isn’t always the best resource for mitigating ambiguities, even if it is becoming the most convenient.

Addressing Pervasive Ambiguity

Knowledge ambiguity isn’t the only learning challenge students use GAI to alleviate. They also turn to GAI to resolve elements of pervasive ambiguity. As a psychological concept, persuasive ambiguity has been linked to concepts such as culture shock (Furnham, 1997), anxiety (Gudykunst & Nishida, 2001), and even social responses to terrorist attacks (Matsaganis, & Payne, 2005). In all of these circumstances, individuals are thrust into new environments, and they struggle against the uncertainty of their situations. Ball-Rokeach (1973) sees that this ambiguity:

arises as an information problem. There is insufficient information to construct a definition of a situation or to select the most appropriate definition from two or more alternatives. It can result from an apparent or real deficiency in the individual’s repertoire of knowledge and experience or from a blocking of input from the social environment. (p. 379)

Similarly, insufficient information about a given writing assignment has been identified as one of the primary reasons writers have a difficult time developing ideas and getting started with their writing process (Clark, 2019). Pervasive ambiguity can muddle the writing process as a writer isn’t sure what to write to best respond to that rhetorical situation. And while students aren’t reporting using GAI to analyze assignment prompts, many are turning to this technology to help them brainstorm how to begin. It seems they are using GAI as an information-exploration tool that can identify their options as they seek to reduce the pervasive ambiguity engendered by new contexts, new content, and new audiences.

In addition to the 81.2% (n=191) of responding GAI users (n=235) who said they’d utilized GAI to help them brainstorm and the 76.3% (n=244) of respondents (n=320) who said their peers had used it to brainstorm, the theme that GAI can help mitigate the challenges of starting to engage with a new writing situation emerged through the survey’s short answer responses. For example, a sophomore biology student who reported using GAI often for a range of assignments said she believes GAI is “[h]elpful in formulating ideas and creating structure.”

Several other respondents believed that brainstorming was the best, most ethical way to employ GAI. A first year biology student who had used ChatGPT to brainstorm and explain concepts for a literary analysis paper and some math problems asserted, “I believe that [GAI] should not be completely banned because it is helpful to students when they are stuck on an assignment but there should be restrictions, such as students cannot have generative AI complete the entire assignment for them, only help them with ideas.” A graduate student in a business program who said they had not used GAI for academic work acknowledged that GAI is “useful in the sense that it can be a tool to brainstorm and explore different ideas. However, it does not replace the function of the human brain and can inhibit critical thinking skills.”

This respondent’s focus on the value of human reasoning reminds us that, just as tutors can still be influential in working with writers through knowledge ambiguity, tutors can and should continue helping students navigate process ambiguity. Writing center tutors have long been positioned as resources to help writers through the uncertainties incurred when encountering a new rhetorical situation—as evidenced by the consistent advice that has appeared in tutor training handbooks about how tutors might structure appointments focused on pre-writing (e.g., Clark, 2008; Ryan & Zimmerelli, 2016). And while GAI is very proficient at churning out topical lists and possibilities in seconds, it’s not as effective in methodically analyzing a rhetorical situation and helping students identify how their personal interests coincide with an assignment’s requirements. Even while we acknowledge that students are turning to GAI to settle learning ambiguities, we need to continue championing the quality, personalized, human assistance that tutors can provide. We also need to consider more closely the additional ambiguities that these tools generate—ambiguities exemplified through that graduate student’s acknowledgement that GAI may be both useful and inhibiting. Because even while writers are using GAI, they aren’t sure what to think about that use.

Engaging With Process Ambiguity

This acknowledged paradox between GAI’s capacity to resolve opening uncertainty and its potential to fundamentally limit learning points to the underlying concerns informing the ambiguity we found across all of these survey results. While students are using GAI to alleviate knowledge and pervasive ambiguity, they are simultaneously unsure about it. This ambiguity about the nature of these tools and their most appropriate usage emerged again and again through hundreds of different survey responses. Of the 289 respondents who completed the “I think GAI is . . .” phrase, 47.1% (n=136) expressed uncertainty about whether or not this developing technology is a good thing or a bad thing. And out of the remaining 221 students who did not express ambiguity about the broad nature of GAI, 52.9% (n=117) expressed uncertainty toward at least one of the Likert scale questions about how GAI can be incorporated into the classroom, GAI restrictions, and/or GAI use in relation to academic integrity policies (Figures 10, 11, and 12). Broad uncertainty about GAI’s value was apparent in how many respondents (n=70) said they hadn’t used these tools because they wanted to learn by doing the work themselves (Figure 6). When it comes to GAI, many students just don’t know. They don’t know what to think about it. They don’t know what it means for their learning. They don’t know how to approach using it. They don’t know if or when to embrace it. Even while GAI may have diminished some ambiguities, it has generated a whole other kind of uncertainty.

We call this uncertainty “process ambiguity.” This is a term that has been used in management scholarship to describe the range of ways a workflow for the development of a new product can be interpreted and misinterpreted (Brun & Sætre, 2009). We recontextualize “process ambiguity” by connecting it to composition study’s long interest in the writing process and see it as an apt way of describing the confusion students are experiencing about GAI. Should they use it for their academic work? If so, which tools should they use? When should they use them? How? If they shouldn’t use it, why? In seemingly mitigating the traditional uncertainties that complicated and furthered learning—ambiguities about acquiring knowledge and locating oneself in relation to an academic context—GAI has raised a whole new set of unknowns. And if “ambiguity can serve as a catalyst for learning” (Nicolaides, 2015, p. 179), then these new unknowns can be as influential in helping students become informed and critical thinkers as earlier ambiguities were. Perhaps the kind of learning that students traditionally engaged with by sorting through knowledge and pervasive ambiguities can now be similarly achieved by working through the challenges of pervasive ambiguity. Opportunities to learn through ambiguity are still here; the focus of that ambiguity has just shifted.

If process ambiguity is one of the dominant challenges students are currently facing as a result of the complicated compositional opportunities available to them through GAI, then writing centers are an excellent resource for helping students and instructors work and learn through these situationally specific challenges. By addressing writers’ process ambiguities, writing centers can productively guide and inform institutional responses to GAI’s affordances and limitations. As such, writing center tutors need to be trained and ready to talk with writers about GAI, and writing center administrators need to be participating in their campuses’ GAI conversations and initiatives.

Writing Center Strategies for Engaging with GAI

As writing center practitioners, we are just starting to identify how GAI can be best addressed through tutor interactions. Deans et al. (2023) have recommended that tutors approach GAI as a writing-adjacent tool and incorporate it into tutorial sessions to help with a range of challenges—from “unblocking a writer” to “shortening and sharpening a thesis statement.” They argue that tutors can turn to ChatGPT in a tutorial session, model effective prompt engineering practices based on the writers’ concerns and the particular rhetorical situation, and work with the writer to discern what to do with the resulting content. Tutors can prompt “some meta-reflection on the process and [emphasize] the writer’s agency in making choices.” But even if an institution’s policies or a center’s philosophical views on composition don’t allow GAI to be used for academic purposes, tutors can still helpfully guide writers through the process ambiguity they may encounter as they decide what to do with GAI.

Empowering Our Tutors

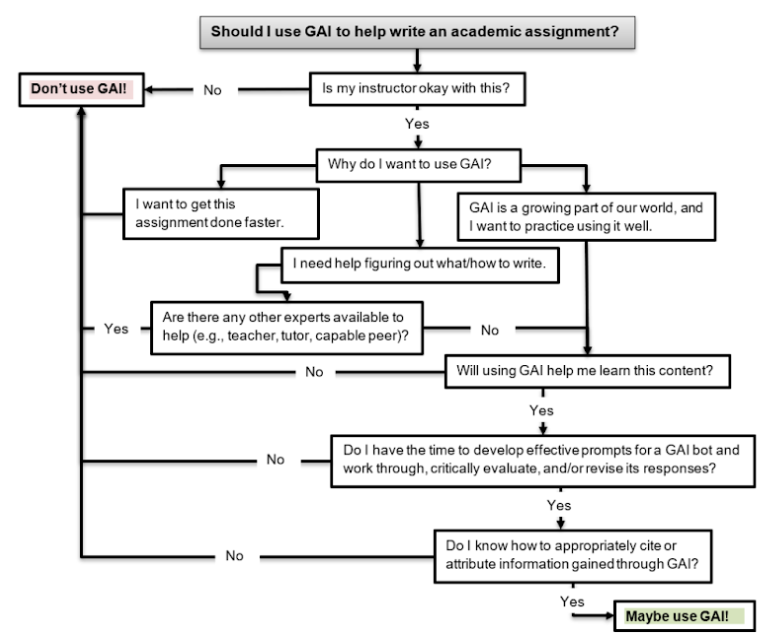

At our center, we’ve started to build content about GAI into our tutor training to prepare our tutors to talk with writers about these challenges. We’ve read and discussed popular press articles about GAI with our tutors (e.g., Marche, 2022; Levy, 2023). We’ve designed staff meetings about GAI in which we’ve explored what it is, how it’s being used by students, and what interaction tutors might have with it in a tutorial session. We’ve assured tutors that they aren’t responsible for “catching” or reporting GAI use, but we’ve also encouraged them to kindly and openly address any GAI-related concerns they might have. We’ve taught them to not be accusatory if they suspect a writer they’re working with has used GAI but to say something like, “You know, this passage kind of reads like something ChatGPT would write. Is that okay?” We’ve developed a decision flow chart that tutors can direct students interested in using GAI toward as a way of helping them evaluate their potential rationale for using GAI (see Appendix C). We want our tutors to be empowered to engage in conversations about GAI use and knowledgeable enough to guide these conversations towards the important issues of motivation, ownership, expectations, and the purpose of education. This is how tutors can help writers learn through process ambiguity—by directly raising and addressing questions about GAI usage through their daily interactions with individual students about the particular writing tasks they engage with in their efforts to develop specific pieces of writing.

Equipping Our Faculty and Staff

In addition to preparing our tutors to help students address the process ambiguities raised by GAI, we have worked to position ourselves within our campus’ wider dialogue about GAI use, response, and policy. As writing program administrators with backgrounds in composition, education, and academic integrity, we have sought and initiated conversations with our on-campus colleagues about GAI, GAI’s place in the classroom, and students’ engagement with GAI. We have partnered with members of our school’s instructional technology team and professors invested in GAI to develop and facilitate three iterations of a workshop entitled “Responding to GAI.” When we’ve run this 4-hour workshop, we’ve received funding from our campus’ Office of Mission Integration to offer the participating instructors (including full-time faculty and adjuncts) stipends and lunch. During this workshop, participants have learned about GAI’s functionalities and models for responding to disruptive technology; tested these tools for themselves; shared how GAI is already influencing their disciplines, workflows, and classrooms; and developed or revised one specific classroom element in response to GAI. Faculty members’ applications have included a prepared mini-lecture and in-class discussion for a biology class about GAI’s data synthesis possibilities and shortcomings, an activity for a nursing class requiring students to use GAI to write a case study and then evaluate the result, a take-home essay prompt for a psychology class that was retooled to make it more difficult for students to use GAI on, and an assignment for a political science course where students “debate” with a GAI bot about a political concept they care about.

By being a part of this workshop, we’ve been able to help faculty members as they, in turn, help students navigate the challenges and possibilities of GAI. It has become a particularly powerful opportunity for us to talk with instructors about key Writing Across the Curriculum values as they consider what GAI means for writing, writing assignments, and writing assessment. We’ve encouraged them to prioritize the learning made possible through the writing process as opposed to focusing on the transactional completion of a writing product. Additionally, we believe that workshops like this one can be an important way to respond to students’ ambiguities about GAI. If instructors are better equipped to teach with, about, and in spite of GAI, then they can address their students’ uncertainties about these resources. Given that only one fourth of the students agreed or strongly agreed with the survey question about receiving instruction about GAI (see Figure 9), more needs to be done to support instructors’ capacity to address GAI in the contexts of their courses. Workshops like these, informed by a writing center’s attention to collaboration; flexible teaching styles; writing as a critical, social, and rhetorical process; and individual students’ experiences, can be one way to respond to this need.

We’ve also paid attention to who has been talking on campus about administrative responses to GAI, and we’ve prioritized attending meetings about academic policy in relation to GAI. As a result, we’ve been able to help shape the official syllabus statements about GAI that our college has developed and encouraged instructors to include in their syllabi. There are three versions of this statement that have been promoted by our college—one that clearly restricts all GAI use, one that specifies that GAI will be allowable in certain situations or with certain assignments, and one that allows for any (documented) GAI use. By being a part of these policy conversations and workshops, we’ve signaled to the campus community that we are willing and able to think through the complications and possibilities of GAI and that we are engaged in the challenges of responding to the process ambiguity GAI raises. This intentional openness has led to numerous additional, individual conversations and consultations with instructors about how they’re talking with students about GAI, revising their teaching practices with GAI in mind, and addressing perceived misuses of GAI.

Enabling a Campus-Wide Response

In fact, this study was inspired by a conversation we had with a faculty member. After participating in one of the GAI workshops, an instructor commented, “We’re thinking a lot about how professors can teach differently in response to GAI. And that’s important, but what do we know about what students are actually doing with these tools?” We were intrigued. By using that question as a catalyst, we were able to directly respond to a knowledge gap that our community was actively interested in learning about. We believe that our high survey response rate was related to a common investment in this issue. We told the various faculty workshop participants and partners about our study and encouraged them to promote the survey in their classrooms, perhaps even using it as a launching point for an in-class conversation about GAI use. After we compiled our preliminary results, we wrote a white paper about our findings and organized a brief info-session. Faculty reviewed the paper we made public and joined our session to consider the implications of these results. By doing this work, we’ve been able to promote a campus-wide response to GAI that acknowledges its disruptive potential while encouraging instructors to work within its capacity to promote student learning. We’ve been able to help instructors work through their own process ambiguities in relation to GAI as they, in turn, consider how writing and writing instruction can remain central to students’ development as thinkers and learners.

We realize that by encouraging writing center administrators to develop workshops, engage in conversations about GAI, and help shape how stakeholders are responding to this technology we are essentially suggesting that our fellow administrators do more things. And given how many things writing center directors already do (Caswell et al., 2016), this may not feel like a welcomed or even viable recommendation. Personally, our capacity to do this work has been bolstered by our intrinsic curiosity in GAI, the institutional support we’ve received as we’ve engaged in these projects, and the administrative benefit we’ve experienced from working in a small writing center staffed by both a director and an associate director. We recognize the role these privileges have played in facilitating our response to GAI. However, given GAI’s position as a critically important, disruptive technology, we stand by our enjoinder that writing center directors participate in this work. We understand that making room for all of these trainings, conversations, and responses might feel untenable, but we believe that not bringing our expertise and perspectives to bear on this situation will actually be much more detrimental in the long run. We need to use the knowledge and insight we have as compositionists who are committed to helping individuals learn through writing. By applying what we know and what we value to these questions of how to respond to GAI use, we can bring instructors’, tutors’, and students’ attention back to the broader purpose of writing and education.

Conclusion

Our survey provided key insight into how students are grappling with a form of ambiguity—the process ambiguity raised by the practical and ethical implications of GAI use. We see that students recognize the need for more engagement around usage of these new innovations—engagement that we believe writing centers can guide both within the individual interactions tutors have with writers and across the more campus-wide and faculty-focused initiatives writing centers develop and promote. Our research findings support the need for a pedagogical response to GAI that openly addresses its ambiguity and doesn’t stigmatize its use but rather harnesses its capacity to support learning. Instead of seeing GAI as a tool that eliminates the uncertainty that has traditionally been heralded as a key facilitator of learning within the writing process, we believe that the new ambiguities it raises can become a motivation for compositional development and critical thought both within and beyond the writing center context.

In his survey response, the marketing major referenced at the start of this paper who had used GAI to draft an assignment reflected that GAI “can be abus[ed], which is why there needs to be a clear guideline, especially in an academic setting, because it is inevitable that students will . . . use this tool.” Given the undeniable presence of GAI in the academic environment and the warranted concern over its capacity to simplify learning processes, writing centers have an opportunity to shape individuals’ perspectives about this technology as we help student writers negotiate the ambiguities raised by its usage and support their instructors as they identify effective pedagogical responses to GAI and GAI use. Whether or not GAI makes completing academic assignments easier or not, it has certainly complicated how writers write and the expectations around their writing processes. And writing center tutors and administrators are well positioned to productively address those complications by defining, talking about, promoting, and modeling critically and rhetorically informed GAI use.

Footnotes

- Since chi-square tests do not support zero, these results are based on the fields in Table 2 that have been shaded blue. Also, to reduce the number of zeros in these results, we combined the “I’ve used GAI all the time” results (n=2) with the results for “I’ve used GAI often” (n=41). ↩

- The respondent who mentioned huxli.ai wrote, “you guys are not going to like this one”—assumedly because of the way huxli.ai positions itself as a human-mimicking content generator that can help students write assignments without being detected. ↩

- While we’re aware that asking respondents to rank GAI’s dangerousness prior to having them complete the phrase, “I think GAI is . . .” may have primed some of them to think negatively about this technology, the preponderance of “ambiguous” and “positive” responses makes us confident that this wasn’t the case for most respondents. ↩

References

Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. (Eds.). (2016). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. University Press of Colorado.

Amoozadeh, M., Daniels, D., Nam, D., Chen, S., Hilton, M., Ragavan, S. S., & Alipour, M. A. (2023). Trust in generative AI among students: An exploratory study. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2310.04631

Ball-Rokeach, S. J. (1973). From pervasive ambiguity to a definition of the situation. Sociometry, 36(3), 378–389. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786339

Barrett, A., & Pack, A. (2023). Not quite eye to AI: Student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00427-0

Brun, E., & Sætre, A. S. (2009). Managing ambiguity in new product development projects. Creativity and Innovation Management, 18(1), 24-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2009.00509.x

Caswell, N. I., Grutsch McKiney, J., & Jackson, R. (2016). The working lives of new writing center directors. University Press of Colorado.

Choudhary, A. (2024). Taming the VUCA world: How generative AI can be your secret weapon. LinkedIn.com. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/taming-vuca-world-how-generative-ai-can-your-secret-weapon-choudhary-oduwc/

Clark, I. L. (2008). Writing in the center: Teaching in a writing center setting (4th ed.). Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Clark, I. L. (2019). Concepts in composition: Theory and practices in the teaching of writing (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Cosgrove, S. (2008). Uncertainty and praxis in the creative writing classroom. Faculty of Creative Arts – Papers (Archive). Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://ro.uow.edu.au/creartspapers/80/

Deans, T., Praver, N., & Solod, A. (2023, August 1). AI in the writing center: Small steps and scenarios. Another Word. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/ai-wc/

Furnham, A. (1997). Culture shock, homesickness, and adaptation to a foreign culture. In M. van Tilburg and A. Vingerhoets (Eds.), Psychological aspects of geographical moves: Homesickness and acculturation stress (pp. 17-34). Tilburg University Press.

Gudykunst, W. B., & Nishida, T. (2001). Anxiety, uncertainty, and perceived effectiveness of communication across relationships and cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25(1), 55-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(00)00042-0

Hall, R. M. (2017). Around the texts of writing center work: An inquiry-based approach to tutor education. University Press of Colorado.

Harris, M. (1988). SLATE (support for the learning and teaching of English) statement: The concept of a writing center. International Writing Center Association. Retrieved May 2, 2024, from https://web.archive.org/web/20170423175304/www.writingcenters.org/writing-center-concept-by-muriel-harris/

Kelly, A., Sullivan, M., & Strampel, K. (2023). Generative artificial intelligence: University student awareness, experience, and confidence in use across disciplines. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 20(6), 12. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.20.6.12

Kirsch, G. (1988). Students’ interpretations of writing tasks: A case study. Journal of Basic Writing, 7(2), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.37514/JBW-J.1988.7.2.06

Levy, S. (2023, December 8). Google’s NotebookLM aims to be the ultimate writing assistant. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/googles-notebooklm-ai-ultimate-writing-assistant/

Mackiewicz, J., & Payton, C. (2022). The so what of so in writing center talk. The Writing Center Journal, 40(1), 72-84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/27203756

Marche, S. (2022, December 1). The college essay is dead. The Atlantic. Retrieved April 30, 2024, from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/

Matsaganis, M. D., & Payne, J. G. (2005). Agenda setting in a culture of fear: The lasting effects of September 11 on American politics and journalism. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(3), 379-392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764205282049

McIntyre, M. (2018). Productive uncertainty and postpedagogical practice in first-year writing. Prompt: A Journal of Academic Writing Assignments, 2(2), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.31719/pjaw.v2i2.26

Nicolaides, A. (2015). Generative learning: Adults learning within ambiguity. Adult Education Quarterly, 65(3), 179-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713614568887

Raign, K. (2017). Learning about something means becoming wiser: The Platonic dialogue as a paradigmatic model for writing center practice. Praxis, 14(3), 32-40. https://doi.org/10.15781/T2DJ58Z3H

Ryan, L., & Zimmerelli, L. (2016). The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors. (4th ed.). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Salazar, J. J. (2021). The meaningful and significant impact of writing center visits on college writing performance. The Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 55-96. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1958

Smolansky, A., Cram, A., Raduescu, C., Zeivots, S., Huber, E., & Kizilcec, R. F. (2023, July). Educator and student perspectives on the impact of generative AI on assessments in higher education. Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, 378-382. https://doi.org/10.1145/3573051

Stern, P. N., & Porr, C. J. (2011). Essentials of accessible grounded theory. Left Coast Press.

Sullivan, P. (2019). The world confronts us with uncertainty. In Adler-Kassner, L. and Wardle, E. (Eds.), (Re)considering what we know: Learning thresholds in writing, composition, rhetoric, and literacy (pp. 113-134). University Press of Colorado.

Suzawa, Gilbert S. (2013). The learning teacher: Role of ambiguity in education. Journal of Pedagogy, 4(2), 220-236. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2013-0012

Van Wijk, R., Jansen, J. J., & Lyles, M. A. (2008). Inter‐and intra‐organizational knowledge transfer: a meta‐analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management Studies, 45(4), 830-853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00771.x

Wolcott, H. F. (1999). Ethnography: A way of seeing. AltaMira Press.

Appendix A

Survey Script

1. Demographic Information:

1a. Gender (multiple choice)

-

- Female

- Male

- Non-binary

- Prefer not to respond

1b. Ethnicity (multiple choice)

-

- Caucasian

- Black/African

- Latinx or Hispanic

- Asian

- Two or More

- Other/Unknown

- I prefer not to say

1c. Age (multiple choice)

-

- 18-24

- 25-39

- 40-59

- 60+

- Decline to state

1d. What is your current status? (multiple choice)

-

- First-Year

- Sophomore

- Junior

- Senior

- Graduate Student

1e. What is your current academic major? If you are undecided, please indicate below. (short answer)

1f. To the best of your knowledge, what is your current overall GPA? (multiple choice)

-

- 3.7-4.0 (A- to A+)

- 2.7-3.69 (B- to B+)

- 1.7-2.69 (C)

- 0.0-1.69 (F to D)

2. Generative AI Use for Academic Assignments

2a. Have you used generative AI technologies like ChatGPT for your academic work? (multiple choice)

-

- Never

- Once or twice

- Several times

- Often

- All or almost all the time.

[If answer for question 2a is “never”]

2b1. Why have you not used generative AI for your academic work? (select all that apply)

-

- I didn’t know I could use generative AI to assist with academic assignments.

- I don’t know how to use generative AI to assist with academic assignments.

- I was told not to use generative AI on academic assignments.

- I don’t feel comfortable contributing my data to helping a large language model improve.

- I was concerned about potential plagiarism or academic integrity issues.

- I thought I could do a better job than generative AI could.

- I wanted to do the work myself in order to learn.

- Other (please describe):

[If answer for question 2a is any response other than “never”]

2c1. What generative AI tools have you engaged with for academic assignments? (select all that apply)

-

- ChatGPT

- DALL-E2

- SpeechifyDo

- Grammarly

- Scribe

- AlphaCode

- GitHub Copilot

- Claude

- Synthesia

- Other: Please describe

2c2. What kind of academic assignments have you used generative AI on? (select all that apply)

-

- Reflection essay

- Argumentative essay

- Literary analysis

- Annotated bibliography

- Literature review

- Research paper

- Lab report

- Summary

- Exam essay

- Discussion post or question

- Creative writing assignment

- Visual art assignment

- Computer coding assignment

- Professional or academic email

- Other (please describe):

2c3. When using generative AI for academic assignments, how have you used it? (select all that apply)

-

- Brainstorm ideas.

- Explain concepts.

- Check my grammar.

- Give me feedback on my writing.

- Develop an introduction.

- Develop body paragraphs.

- Develop a conclusion.

- Synthesize sources.

- Write a full assignment.

- Draft an assignment that I then revised.

- Other (please describe):

2c4. Why have you used generative AI tools on academic assignments? (select all that apply)

-

- It saved me time.

- My instructor encouraged me to use it for an assignment.

- My instructor required me to use it for an assignment.

- I was curious about what the tools could do.

- I needed help figuring out what/how to work on the assignment.

- Other (please describe):

3. Peer’s use of generative AI for academic assignments.

3a. To the best of your knowledge, how many of your peers have used generative AI for their academic assignments? (multiple choice)

-

- None

- A few

- About half

- Most

- All

[If answer to 3a is “none”]

3b. To the best of your knowledge, why have your peers not used generative AI for their academic work? (select all that apply)

-

- They don’t know they could use generative AI to assist with academic assignments.

- They don’t know how to use generative AI to assist with academic assignments.

- They were told not to use generative AI on academic assignments.

- They don’t feel comfortable contributing their data to helping a large language model improve.

- They were concerned about potential plagiarism or academic integrity issues.

- They thought they could do a better job than generative AI could.

- They wanted to do the work themselves in order to learn.

- Other reasons (please describe)

[If answer for 3a is anything other than “none”]

3b. To the best of your knowledge, when using generative AI for academic assignments, how have they used it? (select all that apply)

-

- Brainstorm ideas.

- Explain concepts.

- Check grammar.

- Give feedback on their writing.

- Develop an introduction.

- Develop body paragraphs.

- Develop a conclusion.

- Synthesize sources.

- Write a full assignment.

- Draft an assignment that they then revised.

- Other (please describe):

3b. Why do you think your peers have used these tools for academic assignments? (select all that apply)

-

- It saved them time.

- Their instructor encouraged them to use it for an assignment.

- Their instructor required them to use it for an assignment.

- They were curious about what the tools could do.

- They needed help figuring out what/how to work on the assignment.

- Other (please describe):

4. Your Views On and Attitude Towards Generative AI – Using a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree” respond to the following questions:

4a. Generative AI tools such as ChatGPT can provide me with unique insights and perspectives that I may not have thought of myself.

4b. Faculty should make an effort to integrate use of artificial intelligence tools in their curriculum.

4c. I have received instructions about how to use ChatGPT or similar tools from faculty or staff at Le Moyne College.

4d. Generative AI is dangerous.

4e. Students’ use of generative AI tools to complete coursework is inevitable.

4f. Students should not be restricted from using AI for coursework.

4g. Use of AI text generation tools to complete coursework violates academic integrity policies at Le Moyne College.

4h. Generative AI is going to have a significant impact on my career post graduation.

4i. Complete the following statement: “I think generative AI is …”

5. Students’ Perceptions of Faculty Use and Understanding of Generative AI – Using a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree” respond to the following questions:

5a. Faculty at Le Moyne College have a good understanding of what generative AI tools are and how they should or should not be used for academic assignments.

5b. I would feel confident knowing my instructor was using AI when creating their syllabus.

5c. I trust AI in grading my assignments and assessments for my courses instead of my instructor.

5d. I trust that my instructors are able to recognize AI-generated work versus student-generated assignments.

6. Is there anything else you wish to share about generative AI?

Appendix B

Categorized Examples of Short Answer Responses to the Survey Question Asking Respondents to Complete the Phrase: “I Think Generative AI is . . .”

Appendix C

“Should I use GAI to Help Write an Academic Assignment?” Flowchart