Elise Dixon

The Peer Review, Volume 1, Issue 2, Fall 2017

One day, during a shift as a new writing center consultant, I consulted with a male friend who had made an appointment with me to work on a piece of fiction. We shared classes together, and I knew him well. He and I sat side by side as I read his piece aloud. On this particular day, he came into the center with a piece written from the perspective of a woman. In the story, she was sitting next to a man she found attractive; the sexual tension was palpable. As I read the story aloud, the descriptive details about the man grew clearer: he wore cardigans and ties, had dark hair and a serious demeanor, just like my friend. The details of the relationship between the man and the woman also grew clearer: they were friends, but she had a boyfriend, just like I did. I didn’t think much of the story until, reading aloud, I spoke the moment in which the two characters reached for each other to kiss: the male character ran his hands through the female character’s long red hair. I had long red hair. I suddenly realized this man had come to the writing center having written a story about the two of us making out in the writing center. I stood up, face flushed, pointed to the door and yelled, “GET OUT.” He looked disappointed that his story had not been a self-fulfilling prophesy, but slinked out of the center without another word. I sat back down, and then slid to the floor to sit cross-legged under the table as I gained some composure. Miranda, a fellow consultant and my roommate, crawled under the table to join me: “Elise, you ok?” I recounted the story to her and, after a while, my tears of embarrassment and shame turned into those of laughter.

To this day, Miranda still tells this story to people when we discuss my inability to understand when people are crossing my boundaries until it is too late. I have spent many years laughing about this, but I have also come to see this tale for what it is: not a story of flirting gone horribly awry, but a story of sexual harassment. It wasn’t until I was sexually harassed again—this time by a female writing center colleague—that I began to understand this man’s actions for what they truly were.

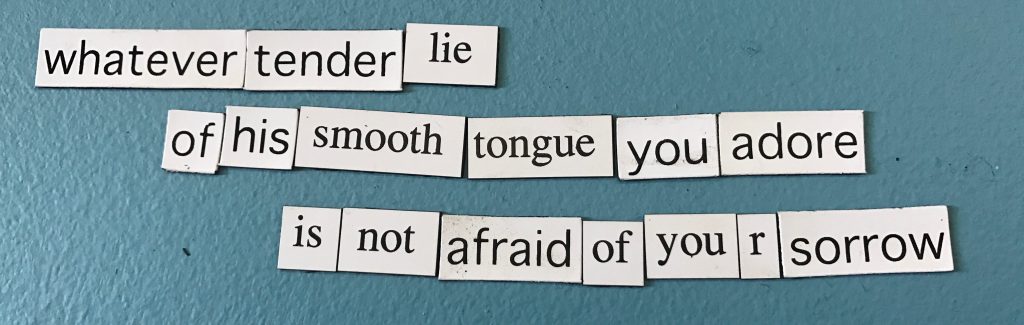

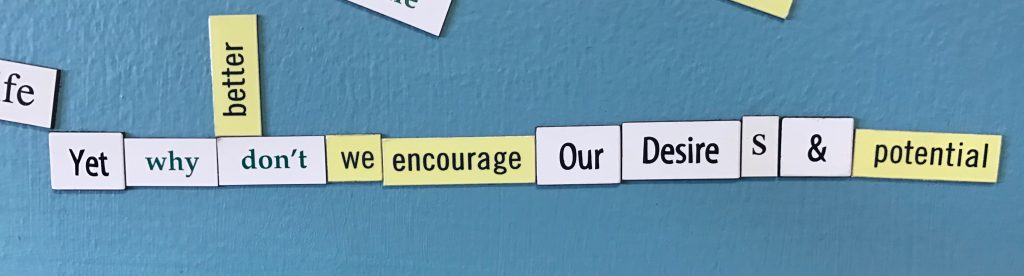

I tell this story to provide an example of everyday moments that occur within writing center walls that we do not often discuss in scholarship. Instead, all too often, discussions of the everyday writing center are about the ways in which tutors bond with one another over coffee and popcorn in the lounge, or about the feel-good moments between client and consultant. Such grand narratives however, often create a tidy but incomplete picture of the writing center (McKinney, 2013). Ann Gellar et al. (2007) call for writing center directors and scholars to “remain open to everyday moments” in the center, suggesting readers consider the everyday chats between consultants during their breaks, the meaning made in magnetic poetry, Internet bookmarks, or unshelved books (p. 56). Indeed, they argue “seeing the everyday in these artifacts is one way to uncover what means and what matters in our writing centers” (p. 58). The contention that there is more to writing centers than the one-on-one consultations is not new. Many scholars have asserted that the importance of the center is in the whole uncomplicated package: the whispered giggles by the watercooler and philosophical discussions on the couch, the “hand-lettered renditions of favorite quotations on the wall . . . jokes on the board . . . work on the tables” (Boquet, 1999, p. 475). While I have had my fair share of these everyday moments, such an uncomplicated depiction of the center without an equal representation of the unsettling, messy, or queer moments does writing centers an injustice. Such one-sided representations paint unrealistic pictures of the moments that make up an individual writing center’s identity. To adhere to, perpetuate, and publicize such a one-dimensional and tidy portrayal of the center without also presenting its messiness keeps us from engaging with the possibilities of such unsettling moments in the center. What kinds of meaning-making do we miss out on when we’re busy trying to find and make public the tidy, easily-categorizable moments?

My messiest moments in the writing center have been imbued with sex, gender, and sexuality. In particular, my experiences of sexual harassment have been perpetrated by both a man and a woman; these two moments, coupled with additional times in which I was shamed for being bisexual, have led me to think about these messy, uncomfortable, and sometimes downright awful writing center moments in terms of queerness and queer theory. Queer people, and by proxy queer theory, are well-suited to address such a complicated mess because queerness revels in the prickly and pleasurable parts of discomfort. Indeed, “‘feeling bad’ has been a crucial element of modern queer experience” (Love, 2007, p. 160). Queer people are particularly equipped to understand and analyze the complexity of emotions and actions possible at any one time through experiences of coming out (or not), fucking (or not), transitioning (or not), loving, losing, world-making, and other hurts-so-good moments. Opening up spaces of discomfort is a key part of the meaning-making process; feeling bad often acts as a catalyst for political change, especially for LGBTQIA+ people.

Thus, in this article, I use a queer framework to address the messy, uncomfortable moments in the writing center because sometimes those moments are queer, and even if they are not, much queer work has been previously dedicated to contending with discomfort. Certainly, there is writing center scholarship that articulates specific uncomfortable everyday moments of racism, sexism, classism, linguistic prejudice, and homophobia in the center (Denny, 2010; Gellar et al., 2007; McKinney, 2013; Greenfield & Rowan, 2013; Grimm, 1996). Often, however, those incidents are discussed as problems that must be solved in order for a writing center to reach its true inclusive potential, and I agree; we must work to create more inclusive and diverse writing center spaces. However, a discussion of these moments as only issues to be eradicated does a disservice to the trauma that occurs in those moments. I will not be discussing the ways in which texts that work towards inclusivity fall short; instead, I hope to expand the discussion on the everyday, and argue for writing center scholars, tutors, and directors to think about how the messy, unsettling, or queer moments in the writing center fruitfully complicate our understanding of what it means to make meaning in the center. Complicating the writing center grand narrative with stories of queerness is a move toward humanizing a space that is often discussed in sterile or rosy terms. While many might suggest the tidy grand narrative works for those who must continually defend their center’s existence, I believe the queer complication I am calling for is necessary for continued academic, institutional, and student support of the writing center.

In addition, it is also not my intention to present these everyday moments of discomfort in order to solve or erase them. Queerness already has a history of being put under erasure, outlawed, or sanctioned against; I do not intend to call for censorship. Nor do I wish to suggest that sexual harassment is always queer or is ever acceptable; I am merely writing from my queer experiences of sexual harassment as a way into a deeper discussion about how upsetting, uncomfortable moments in the center are key parts of our writing centers’ identities. While my experiences of sexual harassment and bisexual erasure were traumatic and I wish they had not happened, I want to discuss the ways in which my experience was made more confusing because the grand narrative of the writing center as a cozy, iconoclastic space ran counter to those experiences. I am calling for a splitting open, a calling out and a calling in, and a magnifying-glassed, wide-eyed stare into these moments as a way to better understand the complicated and queer nature of a space like a writing center.

The Power of Stories

On one of my first days in a new writing center, I disclosed my bisexuality to some queer colleagues. Because I am married to a man, I often pass as straight. Passing privilege is certainly a part of my life, one that I acknowledge and am cautious of in queer spaces. Most often, when I come out, I am met with nods of recognition and the occasional “me too!” but I am also met with some side-eye from LGBTQIA+ and straight people alike. On this particular occasion, we were discussing who should be “allowed” to do queer theory; appropriation was a concern of the folks I was talking with. I broached the topic carefully, suggesting that as a straight-passing person, I often worried that queer people would see my engagement with queer theory also as appropriation, despite my queer identity. The two people I was chatting with blinked and nodded as I spoke, and then continued in their conversation with each other about how annoying it was when straight people appropriated queer practices in the academy. Discouraged, I slinked away from the conversation feeling unacknowledged and unheard; mostly, I began to feel as if my bisexuality was not “queer enough,” at least for my writing center colleagues.

I approach this concept of unsettling everyday moments from a queer framework because my experiences of discomfort in the writing center have been particularly imbued with and connected to my bisexuality. My stories are meant to be placed alongside and in relation to the many sexual, awkward, painful, or queer stories of other consultants, clients, and writing center professionals that occur every day in writing centers across the country. I tell my stories to illuminate the ways in which discomfort play(ed) a central role in my experience as a writing center consultant and professional, and to show, through practice, that the sharing of stories like mine can break open fruitful points of meaning-making.

Telling stories like mine is an opening point for writing center professionals to begin resisting the tidy narratives that misrepresent the messy queerness that exists in the center. There is very little literature on writing centers as queer spaces (Denny, 2005; Doucette, 2011) or on writing centers as spaces where queers have queer experiences. Thus part of my intention for this article is to engage in what Royster and Kirsch (2012) call “critical imagination,” to

look at people at whom we have not looked before . . ., in places at which we have not looked seriously or methodologically before . . ., at practices and conditions at which we have not looked closely enough . . ., and at genres that we have not considered carefully enough . . ., and we think again about what women’s patterns of action seems to suggest about rhetoric, writing, leadership, activism, and rhetorical expertise. (p. 72)

While Royster and Kirsch are calling for the study of communities of women in particular in order to better understand how their practices might inform understandings of writing and rhetoric, I argue here that a study of writing center communities’ queer, complicated, or upsetting practices fruitfully inform our “Idea of the Writing Center.”[1] Royster and Kirsch call for such an examination of women’s communities because they are often overlooked and undervalued, and for this reason, I believe critical imagination can similarly help writing center professionals think about the practices that are neglected, especially those practices that make us feel uncomfortable, upset, or aroused.

Additionally, stories build a web of relations by putting us into relationships with people and their histories. Indeed, stories implicate us in ways that simple analysis or criticism cannot; stories of discomfort or injustice implicate the listeners into that discomfort. Indeed, “the practice of story doesn’t always feel good, and the stories produced in that practice aren’t always happy celebrations of our community’s accomplishments . . .” (Powell et al., 2014, Act II, Scene 3), precisely because they implicate us and call us to action, or at the very least recognition. For this reason, stories help us to “critique the discipline and produce new ways to participate in it” (Act II, Scene 3). Paying attention to the queer, knotty, scratchy stories of everyday moments in the writing center allows us to critique the writing center while producing new ways to participate in it that might honor the complexity of those who make it a community through these practices.

A Story of Harassment and Homonormativity in a Center

In my first year of my graduate program, a female writing center colleague sexually harassed me in a private message over a social media platform. Afterward, I requested she give me some space and suggested we only interact professionally as we took classes and worked in the writing center together. As an abuse survivor, I was afraid to report the incident to the university as previous experience told me such action might lead to retaliation. I spent a lonely, uncomfortable year sharing a working space with a woman who had harassed and then gaslighted me about both the incident and my sexuality when I tried to confront her about the harassment.

As the year continued, I began to hear rumors from other colleagues that I was at fault for the incident, that I was refusing to “get over” an inconsequential experience, and that I was a hypersexual “bisexual predator,” preying on lesbian women, dangling a sex carrot in front of them until they made an advance, only to pull away out of pure malice. During all of this time, I was afraid to tell my story to anyone, for fear that they would report it back to my harasser who would retaliate with nastier rumors. I retreated into myself, considered shifting my concentration of study from queer rhetorics to something else, and found myself hiding in the corners and conference rooms of the writing center to avoid any confrontation at all from my harasser.

The writing center became a space of deep discomfort and trauma for me. I avoided my harasser, slinking to the bathroom whenever she had open time to socialize between clients and hiding in the conference room with my headphones in as I waited for mine. I read any glance in my direction from other colleagues as recognition that they were choosing to believe the story my harasser told them. I searched, at least, for bisexual allies and those who might validate my sexuality and found some. I also found some who still bristled at the fact that a woman married to a man would claim queerness, and further, that such a woman would engage in queer scholarship. I spent my time in the writing center among allies, those I wasn’t sure I could trust, and those who spread rumors and gossiped about me without ever asking me if I was ok, or at least if any of it had been true. The writing center was not my cozy home, and sometimes it was not even a space in which I could engage in the rebellious or iconoclastic queer work I wanted to do. Instead, it became imbued with dark feelings of despair, loneliness, helplessness, all begotten from the fault lines around sex, desire, sexuality, and unwanted advancements.

The Everyday Queer Writing Center

Writing centers are built through everyday communal practice—and sometimes those practices can look like sexual harassment and gossip—and those practices build community. Indeed, community-building itself is a practice, made up of individual actions that reflect and are reflected by community values. From a cultural rhetorics perspective, “cultures are made up of practices that accumulate over time and in relationship to specific places. Practices that accumulate in those specific places transform those physical geographies into spaces in which common belief systems can be made, re-made, negotiated, transmitted, learned and imagined” (Powell et al., Act 1). An individual writing center community, then, gets created and defined through practices that accumulate over time to create common belief systems. Such belief systems lead to what McKinney, drawing from Lyotard, calls the writing center “grand narrative.” Two of these grand narratives, that writing centers are iconoclastic and that they are cozy homes, are common beliefs guided by common practices. For instance, McKinney suggests choices of furniture and other accessories (like couches, coffee makers, bookshelves and plants) contribute to the grand narrative of cozy homes. Additionally, lore about writing centers often positions them as marginal and liminal, an embrace of which could, according to Harry Denny (2005), mark a center as queer in its liminality: “like queer people, writing center professionals continually confront our marginality: we daily encounter students and faculty alike who approach our spaces with uneasiness” (p. 97). However, many writing center professionals would argue this uneasiness is unnecessary because writing centers are supposedly safe, conversational, nonhierarchical places. And yet, I have experienced approaching my own writing center with uneasiness; it has, at times, been a space of great discomfort, a discomfort only made more perplexing because it has often also been a safe space for me. The grand narrative of the writing center as a safe space puts writing center consultants and clients who do not feel safe at fault for feeling as such; for how could someone ever feel uncomfortable in such a decidedly comfy place?

Yet, most writing center directors, including Gellar et al., would also acknowledge that their writing centers are not always tidy, happy, uncomplicated, cozy, or even iconoclastic (at least not in the cohesive “this whole center is full of rebels” kind of way). Yet, much literature keeps these everyday moments to a minimum, or only discusses them in terms of how to solve systemic inequalities that have infiltrated the writing center’s “sacred” space. Instead, queer, uncomfortable, and messy moments are discussed in whispers behind closed office doors. While Denny (2010) suggests that the writing center community doesn’t “have a code or widely agreed consensus about performativity” (p. 149), McKinney suggests otherwise. She writes, “the story we keep about our work is one of our membership badges; we can discern outsiders by those who stray from the narrative” (p. 4). Thus it is the comfortable narratives that we choose to see in our centers. The queer or upsetting practices that occur in our centers stray so far from our perceived understanding of what makes up a center that they are either ignored or are, perhaps worse, so unrecognizable as to be rendered invisible. Like Boquet (1999), “too often, I’ve felt that my life in the writing center was a secret one…as I search for a positive spin on one of the writing center’s less than successful ventures” (p. 464). Keeping discomfort, pain, depression, anger, desire, or sex out of writing center discourse does not keep those feelings out of everyday writing center practice. Gossip, sexual tension, tearful arguments, seduction, anxiety attacks, and sexual harassment also make up the everyday practices that define a writing center. It is critical for writing center scholars to “bring to light the clandestine forms taken by the dispersed, tactical, and makeshift creativity of groups or individuals already caught in the nets of the ‘discipline'” (De Certeau, 2011, p. xiv-xv). We must not hide or tidy up these queer stories; instead we must tell them, listen to them, and embrace them as a distinct part our writing centers.

Narratives of comfort put writing centers at a standstill because they allow us to be complacent. Sarah Ahmed (2006) explains comfort as “a feeling that tends not to be consciously felt . . . Instead, you sink. When you don’t sink, when you fidget and move around, then what is in the background becomes in front of you, as a world that is gathered in a specific way. Discomfort, in other words, allows things to move” (p. 154). Identifying uncomfortable practices and occurrences in our writing centers and claiming those practices as a critical part of our centers’ identities allows for more dynamism and possibility. For example, recognizing that sexual harassment is a relatively common occurrence in the center allows for directors to create space to talk with their consultants about it. Or, as is the case of my current center, acknowledging that queer consultants are already using the writing center as a space to share queer stories turned into the creation of a queer student group and a small yearly queer conference.

Moving away from comfortable or commonly held beliefs surrounding what “counts” as writing center practice in order to see and embrace other, queerer forms of meaning making calls for what Ahmed calls disorientation: losing one’s sense of “direction,” both literally and figuratively. She argues “moments of disorientation are vital. They are bodily experiences that throw the world up, or throw the body from its ground” (p. 157). Choosing to acknowledge, seek, enact, and address the queer and messy moments in the writing center is one way to disorient away from comfortable grand narratives. Such an embrace will likely be bodily and emotionally awkward for some, though liberatory for many (especially those who have been bodily and emotionally uncomfortable themselves as they experienced “unsanctioned” practices in the center). A queer disorientation away from tidy, comfortable, and normative grand narratives reorients us to new forms of iconoclastic disruptions. Since “queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one,” (Edelman, 2004, p. 17) traditional lore or narratives of the writing center can be fruitfully disturbed through a critical examination of queer practices that make up the center. Thus, first and foremost, addressing the complicated, upsetting, and queer practices of the writing center opens it up to new possibilities.

It may seem counterintuitive to seek out, specifically, stories of practices that elicit feelings of loss, hopelessness, or despair as my previous story did; however, it is vital to address negative emotions in particular as a way to also provoke activist thinking among writing center community members. Tapping into the negative in order to provoke change has been an unfortunate necessity of queer life; consider, for example, that a riot outside the Stonewall Inn was the birthplace of Pride, or that the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s was a central factor in the fight for LGBT rights. According to Love (2017), “Queers are intimately familiar with the costs of being queer—that, as much as anything makes us queer . . . The question is not whether feelings such as grief, regret, and despair have a place in transformative politics: it would in fact be impossible to imagine transformative politics without these feelings” (p. 163). Negative emotions are what move us from the sinking complacency of comfort. To make public the “darker” moments of the center as part of its identity—the panic attacks, the gossip, the sexually explicit experiences, the tearful goodbyes—is to move the center out of the closed circuit of meaning made through a passive perpetuation of the grand narrative and into a more complicated expansion of meaning. A consideration of negative emotions caused by uncomfortable everyday moments creates “new spaces—we expand the very space occupied by our bodies, as an expansion that involves political energy and collective work” (Ahmed, 2006, p. 155). In seeing the uncomfortable everyday moments as especially valuable to our understanding of what practices make up a writing center, we open up the space for clients, consultants, and professionals to do the collective work of meaning-making in and out of the center.

I do not mean to suggest that paying attention to the painful, messy, sexual, or queer everyday moments in the writing center will lead to a queer activist utopic vision. In some ways the writing center grand narrative as “comfortable, iconoclastic places where all students go to get one-to-one tutoring on their writing” (p.3) is already an unattainable utopia, as McKinney (2013) aptly argues. Thus, instead of suggesting that such a consideration of the messy everyday moments would create new possibilities, my search for these possibilities is

a search for utopia that doesn’t make a simple distinction between good and bad feelings or assume that good politics can only emerge from good feelings; feeling bad might, in fact, be the ground for transformation. Thus . . . it’s also about hope and even happiness, about how to live a better life by embracing rather than glossing over bad feelings. (Cvetkovich, 2012, pp. 2-3)

Uncovering or breaking open to expose discomfort in the center is not an endeavor to be undertaken simply to solve a problem, or even necessarily to find “hope” in these new possibilities. I am unsure of how this kind of disorientation will impact us all as writing center professionals. However, “The point is what we do with such moments of disorientations, as well as what such moments can do—whether they can offer us the hope of new directions, and whether new directions are reason enough for hope” (Ahmed, p. 158, my emphasis). While we often see hope as inherent in trying something new or different, in moving in another direction, such an assumption may be too extreme. To change directions is simply an act of reorienting; while hope may not always be a part of this equation, mystery certainly is. Perhaps the questions is not “how to cultivate hope in the face of despair, since such calls tend to demand the replacement of despair with hope” (Love, 2007, p. 163). Perhaps the question is about how to embrace the discomfort of not knowing.

Queerly embracing discomfort in this way can push deeper into McKinney’s (2013) desire to “complicate the writing center narrative in ways that include what now lies at the periphery of our work” (p. 6). Perhaps because of its (perceived) marginal status, writing centers are often described in terms of their successes, their inclusivity, their productive noise generated from conversations (Boquet, 2002), their capacity for making “better writers, not better writing” (North, 1984, p. 438), in order to prove their worthiness within the university at large. Indeed, complicating such a writing center narrative, specifically with narratives of discomfort, messiness, or queerness likely seems counterintuitive, especially to writing center professionals who continually fear losing funding, space, or staff. However, I argue that such a queer complication of the center’s positive grand narratives is necessary for the lifespan of writing centers. Trust me: nobody thrives under repression. An adherence to and perpetuation of normative grand narratives closes the center off to new possibilities and instead creates a closed circuit of meaning. Writing center professionals should “attend to the possibility of ‘making peace with’ or ‘being in the room with’ . . . the ‘mess’ or affective intensities by engaging the mess in its ordinariness instead of as inherently traumatic” (Berlant and Edleman, 2014, p. 64). These queer or messy moments are not necessarily always (or even often) traumatic; instead they are comically common. Closets are dark places; I encourage writing center professionals to come out of their “closets” stacked with tidy, comfortable narratives and instead embrace the sex, joy, pain, anger, and anxiety that is already occurring in their centers anyway.

Fuck It All Up

As I said in the beginning of this piece, I am calling for a splitting open, a calling out and a calling in, and a magnifying-glassed, wide-eyed stare into these moments as a way to better understand the complicated and queer nature of a space like a writing center. Such a breaking open and a blowing up will likely put writing center professionals in the position to recognize and make public the writing center’s “less than successful ventures” (Boquet, 1999, p. 464), or more plainly, failures. I wonder, however, if it would be so bad to come to terms with the writing center’s queer failures. For, according to Jack Halberstam (2011),

To live is to fail, to bungle, to disappoint, and ultimately to die; rather than searching for a way around death and disappointment, the queer art of failure involves the acceptance of the finite, the embrace of the absurd, the silly, and the hopelessly goofy. Rather than resisting endings and limits, let us instead revel in and cleave to all of our own inevitable fantastic failures. (p. 187)

If the queer art of failure is an embrace of the finite, then it might be most telling that I am arguing for a consideration of and an embrace of queer everyday moments. The everyday is forever in the present; it has no future. Similarly, “there are no queers in the future as there can be no future for queers, chosen as they are to bear the bad tidings that there can be no future at all: that the future, as Annie’s hymn to the hope of ‘Tomorrow’ understands, is ‘always/A day/Away'” (Edelman, 2004, p. 30). If tomorrow is always a day away, then the everyday serves a particularly perfect metaphor for queer failure. The everyday is forever in the present: It will never reach into the future or gesture back into the past. The everyday is also finite: Once a moment occurs it is over. Everyday uncomfortable moments are queer because they refuse not only our conception of the writing center grand narrative, but they also disrupt our notions of time and cultural reality. Indeed, “. . . queer failure is not an aesthetic failure but instead a political refusal. It is a going off script, and the script in this instance is the mandate that makes queer and other minoratarian cultural performers work not for themselves but for distorted cultural reality” (Munoz, 2009, p. 177). In offering up a breaking open of the messy everyday moments of the writing center, I hope to offer up the opportunity for writing center professionals, consultants, and clients to go off-script of the grand narrative of the writing center as a tidy, uncomplicated, straight, comfortable space.

Like Denny (2010), “recipes for ‘how to’ are not so interesting to me as the questioning of ‘what makes possible’ dynamics that might go unrecognized” (p. 88). In telling my own personal stories, I hope to have enacted what I am calling for of writing center professionals: to tell, listen to, look out for, and engage with stories of the messy, uncomfortable, upsetting, queer everyday moments in writing centers in order to better understand them as complicated spaces of possibility. I am interested in what it might mean for us if writing center professionals begin to claim their messes as integral parts of their writing centers; if writing center professionals were willing to come to terms with their queer failures and indeed embrace them as a critical part of their (and their writing center’s) identities. I admit, I do not know what such a coming to terms looks like, and I am unsure of its aftereffects. Sharing my own stories puts me at risk both personally and professionally, but I am doing so because I believe it may be an important step to acknowledging and embracing the messiness of the center, a space I have come to love despite and because of the (dis)comfort it has caused me. Such a choice to “come out” is unpredictable, messy, and uncomfortable. For these very reasons I’m coming out of this closet, choosing to queerly fail. You can too.

About the Author

Elise Dixon is a third-year doctoral student and writing center fellow in Writing, Rhetoric and American Cultures at Michigan State University. Constellating queer, feminist, multimodal and cultural rhetorics as foundations for her work, Elise has focused her inquiries on the composing practices of queer writers, military wives, and writing center consultants and clients. She currently works as a consultant and graduate writing group facilitator at the Writing Center at MSU and holds fellowships with the Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative and InsideTeaching MSU.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology: Orientations, objects, others. Durham: Duke UP.

Berlant, L., & Edelman, L. (2014). Sex, or the unbearable. Durham: Duke UP.

Boquet, E. (2002). Noise from the writing center. Logan: Utah State UP.

Boquet, E. (1999). ‘Our little secret’: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication 50(3), 463-482.

Bruffee, K. (1984). Collaborative learning and the conversation of mankind. College English 46(7), 433-46.

Cvetkovich, A. (2012). Depression: A public feeling. Durham: Duke UP.

De Certeau, M. (2011). The practice of everyday life. 3rd ed., Oakland: University of California Press.

Denny, H. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-on-one mentoring. Logan: Utah State UP.

Denny, H. (2005). Queering the writing center. The Writing Center Journal 25(2), 39-62.

Doucette, J. (2011). Composing queers: The subversive potential of the writing center. Young Scholars in Writing 8, 5-15.

Edelman, L. (2004). No future: Queer theory and the death drive. Durham: Duke UP.

Gellar, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., & Boquet, E. (2007). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Logan: Utah State UP.

Greenfield, L. & Rowan, K. (Eds.). (2013). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. Logan: Utah State UP.

Grimm, N. (1996). The regulatory role of writing centers: Coming to terms with a loss of innocence. The Writing Center Journal 17(1), 5-29.

Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Durham: Duke UP.

Love, H. (2007). Feeling backward: Loss and the politics of queer history. Cambridge: Harvard UP.

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Logan: Utah State UP.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. New York: NYU Press.

North, S. (1984). The idea of the writing center. College English 46(5), 433-46.

Powell, M., Levy, D., Riley-Mukavetz, A., Brooks-Gillies, M., Novotny, M., & Fisch-Ferguson, J. (2014). Our story begins here: Constellating cultural rhetorics. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture 18. Retrieved from http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here/

Royster, J. J., & Kirsch G. E. (2012). Feminist rhetorical practices: New horizons for rhetoric, composition and literacy studies. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP.

- I use this phrase to denote what McKinney (2013) calls the “grand narrative” (a phrase derived from Lyotard) of the writing center. I argue our “Idea of the Writing Center” stems from North’s (1984) work of the same time, as well as Bruffee’s (1984) “Collaborative Learning and the Conversation of Mankind,” both deeply influential to writing center practitioners’ conception of what a writing center should be “about” and both published in the same journal and year. Of course, these are not the only scholars who have influenced our grand narratives, but I mention these two as formative contributors toward what it means to do writing center work. ↑