Mary Hedengren

Abstract

As linguistic diversity increases on American campuses, writing center staffs are also becoming more diverse— although there has been little empirical research about non-native English speaking (NNS) tutors. Concerns about the native speaker fallacy, although prevalent in TESOL literature, are less documented in writing center studies. The primary purpose of this study is to determine what, if any, differences exist between the tutoring methods of native English-speaking (NES) and non-native English speaking (NNS) tutors and whether some of these differences might be ascribed to linguistic bias. In this study, eight writing center tutors, four NES and four NNS, were observed during sessions with one NES and one NNS writer each. Sixteen naturalistic sessions were transcribed and triangulated with interviews and exit surveys with all participants. Tutor language t-units from these sessions were coded into four broad categories and seven sub-categories. The results indicate that while NES and NNS tutors generally use similar types of language while tutoring, the NES tutors are more directive with NNS writers, reflecting traditional writing center training. NNS tutors are more directive overall, but are especially directive with NES writers. Results also indicate that, despite popular wisdom to the contrary, NNS tutors are less emotionally responsive while working with NNS writers than with native English speakers. The tutors and writers in this study did not indicate the native speaker fallacy as greatly impacting their sessions.

Keywords: Non-native speakers of English, peer tutoring, writing, native speaker fallacy

Introduction

Assumptions of linguistic heterogeneity within American universities are collapsing. Although political factors, including the recently upheld travel ban, have impacted the enrollment of international students in American colleges, multilingual students continue to have a strong presence. For some, that presence is troubling. The Atlantic recently reported some of the panelists at their Aspen Ideas Festival expressed concern that international students made up such a high percentage of students at some universities, perhaps to the detriment of American-born students (Wong, 2018). Inside Higher Ed, on the other hand, is more anxious about the recent dip in international enrollment, despite overall high percentages of international students and some universities reporting an increase in international students (Redden, 2018). These concerns come after a decade of growth during the early 21st century.

The World Education Services (Choudaha, R., & Chang, L. 2012) reported that the increase had been unevenly distributed where some schools, such as the University of Iowa, experienced a quadrupling of international student enrollments since 2006, while the University of California system schools saw a 66.4% increase in international student applications between the 2011 and the 2012 school year (pp. 13-14). The same report describes that in 2009, 20% of international students worldwide were hosted in U.S. schools (p. 7). A more cosmopolitan university population transforms the focus of educational services beyond the classroom. The writing center, historically essentialized as a “fix-it” shop for non-standard student writing (North 1984), has become a defensive resource for administrators seeking to accommodate English language learners on their campuses. And writing centers are generally eager to help these multilingual student writers. The writing center philosophy, focused on creating a safe place for writing outside of the grades and peer expectations of the classroom, often genuinely validates other writing cultures (Barwashi & Pelkowski, 1999).

As educational institutions within the United States serve a more linguistically diverse population, writing center studies have incorporated the research of contrastive rhetorics to train tutors to recognize, interpret, and advise on writing by non-native English-speakers (NNS). Research focusing on aiding NNS writers has been published in journals such as The Writing Center Journal, Journal of Second Language Writing, and College English. Both the Longman’s and the Bedford’s handbooks for writing tutors now include long sections about NNS writers. Also, stand-alone books, such as Dudley Reynolds’ (2009) One on One with Second Language Writers and Bennett A. Rafoth’s (2015) Multilingual Writers and Writing Centers, seek to support native English-speaking (NES) tutors working with NNS writers.

Although NNS writers are frequently subjects of writing center research and practice, the experiences of NNS tutors are often neglected. Writing center journals now feature articles written by directors of writing centers in Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. At International Writing Center Association conferences, NNS tutors and writing directors from both English-speaking and multilingual writing centers participate and present in the proceedings. While there is no direct census of how many NNS tutors there are in American writing centers, they may constitute a significant amount of writing center tutors. For instance, at our large public university in the American South, NNS tutors make up between 8 and 11% of all tutors during a regular school year, and triple that percentage (25-30%) in the summer months.

The contributions of NNS tutors are often neglected in discussions of how NNS writers are best served. Even though Rafoth (2015) acknowledges the contributions tutors “learning another language or who have sufficient experience with non-English-speaking cultures” (p. 123), he suggests that advanced NNS writers would “benefit from a native speaker’s intuitions and corrections” (p. 46) and NES tutors could “serve as both translator and model” (p. 78) for these writers. Rafoth (2015) isn’t the first writing center scholar who recommends that NES tutors could be models. Susan Blau, John Hall and Sarah Sparks (2002) recommend that writing center tutors should act as “cultural informants” (p. 29) or “cultural counselors” who are positioned in a “middle ground” (p. 32) for NNS writers. The (presumably NES) tutors she interviewed at an American writing center all agreed that NNS writers are somehow just different. Blau et al. (2002) expresses the sentiment, common in writing center research, that “tutoring NNS students requires different strategies from tutoring NES students” (p .25). But what if the tutor is also a NNS? The claims of these and other scholars rest on an assumption that the tutor is a native English speaker, something that is less likely to be true in the face of changing writing center demographics.

For instance, Terese Thonus (2004) admits that as “our centers fill with NNSs of diverse backgrounds, we can ill afford to ignore our tutors’ frustrations” (p. 240), but she assumes that her tutors are frustrated native speakers of English, not those who have similarly struggled with writing in a foster mother tongue. In Thonus’ (2004) study of dozens of sessions between NES tutors and both NES and NNS writers, the discussion focuses on what she describes as the “NNS writer’s unshakeable belief in the authority of the writing tutor” (p. 236). But at the end of her work, she suggests further study on “whether NNS writers should be trained to act and think like N[E]S writers and whether tutors should receive training for what many perceive as different practice (with NNSs)” (Thonus, 2004, p. 240).

In a changing linguistic landscape, we might alter Thonus’ (2004) question: instead of asking whether NNS writers should be trained to act and think like NES tutors, we might ask whether NNS tutors be trained to act and think like NES tutors. Should NNS tutors receive training in how to work with those who may hold linguistic prejudice against them? Do our NNS tutors have the same “unshakeable belief” in their own authority that Thonus (2004) suggests NNS writers have in their NES tutors? These questions don’t have easy answers, but they are questions that are worth investigating. It is valuable to think that our writing centers are filling with NNS of diverse backgrounds on all sides of the tutorial table, as tutors as well as writers.

Resituating NNSs as tutors rather than exclusively writers can change writing center studies’ perspective on what is sometimes perceived as a deficit position. In the publications cited above and others like them, NNSs are sometimes portrayed as the “other”—the outsiders who come into the writing center seeking tutors’ expertise, expertise that comes largely from a few weeks of training, some in-house workshops, and the largely unstated assumption that their native fluency will equip them to address NNSs’ writing concerns.

This assumption is known in the field of teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) as the “native speaker fallacy” (Phillipson, 1992)—the idea that merely by being a native speaker of English, the tutor or teacher is automatically more linguistically competent, more aware of language conventions, and, somehow, better at communicating those conventions to a learner. Such assumptions are problematic, but that doesn’t make them less accepted as conventional wisdom among tutors, writers, university administrators and writing program administrators. If tutors are to be, as Blau et al. (2004) suggest, “cultural informants” (p. 29) and “cultural counselors”(p. 32), or in Rafoth’s (2015) phrase, “translators and models” (p. 78), the question arises: are non-native English speakers less valuable tutors in the writing center?

Rather than seeing NNSs in a position of deficit that the writing center can remediate, some scholars have suggested that NNS tutors have unique qualifications, making them even better tutors than their NES colleagues. While empirical research on the topic is lacking, scholars like Nancy Grimm (2009) and Suresh Canagarajah (2006) have argued the theoretical benefits of including NNS tutors in the writing center. Grimm (2009) has called for more linguistically diverse writing centers because NNS tutors may approach the tutoring session with additional perspectives and strategies. She suggests that tutors who generally “have always negotiated more than one language and more than one dialect, one culture, and one identity” (emphasis in original, Grimm, 2009, p. 18) can provide powerful insights into tutoring college writing, itself often a new language, dialect, culture and identity even for monolingual writers. Canagarajah (2006) shares a similar view of the advantages of hiring NNS language tutors and instructors. He emphasizes that “a bilingual person’s competence is not simply the sum of two discrete monolingual competences added together” (Canagarajah, 2006, p. 589). The very act of what Canagarajah (2006) calls “shuttling” between languages is at the root of communication To extrapolate, instead of looking at tutors as gatekeepers of cultural and linguistic competence, writing center directors ought to seek tutors who exemplify the negotiation of language itself. If Blau et al. (2002) and Thonus (2004) say that NNS writers benefit from working with NES tutors, Grimm (2009) and Canagarajah (2006) suggest that all writers would benefit from NNS tutors’ unique linguistic perspectives and skills.

With philosophical arguments on both sides, there is very little empirical evidence of what actually goes on in the writing session with a NNS tutor. One of the only studies of NNS tutors is found in Tzu-Shan Chang’s (2011) dissertation work for the University of Illinois at Carbondale. Chang (2011) observed and interviewed NNS tutors and their writers at her institution. In her findings, the NNS tutors’ linguistic status was perceived as a weakness for both NES and NNS writers. In an extreme case of the native speaker fallacy at work, some of her participant NNS tutors reported even being rejected by potential writers. NNS writers explicitly told Chang (2011) that they would prefer NES tutors because they assume that such tutors would have a better grasp of the English language. Chang’s (2011) findings support reports by Donald L. Rubin and Kim A. Smith (1990) that NNS teaching assistants suffer from the native speaker fallacy when they speak or write with an accent. Not only did NNS tutors in Chang’s (2011) study feel criticized by their writers, but they also were reportedly ambivalent about the non-directive, non-evaluative method and approached tutoring more like assertive teachers.

Chang (2011), like many writing center studies scholars, takes for granted the standard of tutoring non-directivity. For many writing centers, non-directivity, complemented with emotional responsiveness, is traditionally invoked as a key goal of tutoring[1]. In foundational texts like Stephen North’s (1984) “The Idea of the Writing Center” and Jeff Brooks’ (1991) “Minimalist Tutoring,” writing center pedagogy defined itself as a counterpart and remedy to direct instruction and editing. To quote from Brooks (1991), “Fixing flawed papers is easy; showing the students how to fix their own papers is complex and difficult. Ideally, the student should be the only active agent in improving the paper” (p. 4). To facilitate such non-directive approaches, Brooks (1991) recommends a series of concrete strategies, such as sitting abreast, not across, from writers, having the writer hold the pencil for corrections, and encouraging the writer to do most of the talking (pp. 3-4), all to ensure that “[t]he tutor [takes] on a secondary role” (p. 2).

Non-directivity, although a key element in many traditional writing centers, is not unchallenged. Only four years after Brooks (1991), Linda K. Shamoon and Deborah H. Burns (1995) call non-directivity the “orthodoxy” of “pure tutoring” (p. 134) and suggest that alternative methods like directive tutoring can be effective (pp. 140-148). If non-directivity is orthodoxy and directivity is alternative for the NES majority, the reverse is true in traditional writing center discussion of NNS writers. In such tutor handbooks as The Bedford Guide for Writing Tutors (2016) and The St. Martin’s Sourcebook for Writing Tutors (2011), and in writing center journals like WLN, scholars like Sharon A. Myers (2003) and Jane Cogie, Kim Strain and Sharon Lorinskas (1999) recommend relaxing non-directivity in addressing NNS writers, while simultaneously exercising more empathy[2]. In other words, although non-directivity is the standard for many writing centers, these texts suggest that tutors can take a break from being non-directive with NNS writers. Chang’s (2011) research indicates that NNS tutors depart from traditional non-directivity practices in their sessions, but she did not observe any actual tutoring sessions, instead focusing on interviews with NNS tutors.

Where does this leave research on NNS tutors in the writing center? NNS tutors may be an incontrovertible asset, as Grimm (2009) and Canagarajah (2006) argue, or they may be imperfect cultural ambassadors for other NNS students, as Blau et al. (2002) and Thonus (2004) seem to imply. They may be vulnerable, as Chang’s initial research indicates, feeling unsupported by writing center pedagogy and subjected to native speaker bias. Writing center scholars must take this under-represented group into consideration, not just as an abstraction, but as a collection of individuals, each with complex linguistic backgrounds and tutoring practices.

Methods

In order to better understand how NNS tutors work, the current study observes NNS tutors at work in the organic environment where they actually meet with writers. In addition, this study expands the sample of NNS tutors and compares them with NES tutors as a control group. Observations of ecologically valid tutoring sessions are triangulated with interviews conducted both before and after the sessions and with short, sliding-scale surveys administered after the sessions.

Participants

Because this study seeks to identity what, if anything, differentiates the practices of NES and NNS tutors, the participants consisted of 8 tutors (4 NES and 4 NNS) and 15 writers (8 NES and 7 NNS) at a large, public university in the American South. This was a 2×2 study that required both NES and NNS tutors and writers. All participants, tutors and writers, were recruited according to the guidelines of the IRB approval for the study. Participants volunteered to participate based on their availability. All participants were asked if they were comfortable being observed and taped. Audio of those sessions was recorded on a secure digital device until it could be transcribed and then the files were deleted.

Both NNS and NES tutor participants were representative of the population at the writing center at the time of the study; the NNS tutor participants represent between half to a third of all of the NNS tutors and the NES tutor participants represent a third of all NES tutors. NNS tutors made up between 8 and 11% of all tutors employed at this institution during the school year, and up to 30% during the summer sessions. The participants included six graduate students and two undergraduates.

All of the tutors had been trained in this center’s emphasized pedagogy of non-directive, non-evaluative, and emotionally responsive methods, with the undergraduates having taken an entire semester-long course focused on these methods. Non-directive and non-evaluative methods are valued in training and practice at this writing center. According to the center’s website at the time (2010-2016), “Our services are not designed to fix writing ‘problems.’ Instead, we support students as they hone their skills.” Small placards reiterating these policies stand on each table in the writing center to reinforce the tutors’ verbal explanation of the practice to writers.

Training for all of the tutors included information on working with NNS writers. This training usually took the form of conventional writing center wisdom from the Bedford and Longman handbooks, both of which were alluded to in training. These tutors were taught by peer mentors, directors, and directed readings that NNS writers desire more directivity and more emotional support than NES tutors.

The four NNS tutors self-identified as NNSs for the purpose of this study. Each of the NNSs came from a different language and cultural background: one spoke East African French, one spoke Mexican Spanish, the third spoke Italian, and the last grew up speaking Mandarin Chinese in America. They represented many levels of education, from a senior undergraduate to a post-doctoral fellow. Their ages ranged between early twenties to mid-thirties. The four NES tutors, like the NNS tutors, had a variety of educational experience, from a recent bachelor’s graduate to an advanced PhD candidate. Their ages were similar to the NNS group and they were similarly experienced with writing center work.

Inclusion in the group of 7 NNS and 8 NES writers in the study was determined entirely by self-affiliation on the writing center’s standard intake form. At this writing center, all writers were encouraged to self-identify their linguistic background before a tutoring session. Self-identification does have its limitations: those who identified as native speakers of English were categorized as such, although two of the eight NES writers later revealed in interviews that their parents spoke another language in the home. Because self-identification was the sorting mechanism, those writers were not reassigned a designation they did not give themselves. There were only 7 writers in the NNS category because one of the NNS writers participated in two different sessions: first with a NNS tutor and then, weeks later, with a NES tutor. All writers gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Procedure

Before observing sessions with the participant tutors, I conducted in-depth interviews with six NNS tutors about their perceptions of writing center work, how it compared to their previous experiences learning English, and whether they felt discriminated against in the writing center. Although not all interviewees were observed, and these interviews are not described in depth in the current article, the interviews provide additional support for the findings of the observed sessions.

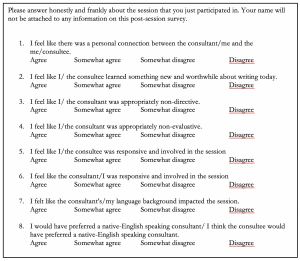

Observations of sessions involved three steps. First the sessions between writers and tutors were observed and recorded, then all participants filled out a short post-session survey about attitudes and perceptions (see Appendix A). Finally, all tutors (NNS and NES) were interviewed about their impressions of the session and their survey responses.

This study attempted to not interfere with the usual practice of the tutors and writers, except as ethical research demands. Writers were invited to participate in the study prior to their scheduled session with a participant tutor. Most of the potential writer participants agreed to have their sessions observed, with the exception of one writer, who declined because her paper included sensitive information. Otherwise, the involvement of writers was organic—writers that would have ordinarily been paired with the participant tutors were the ones who became involved in the study. This method of pairing helps to ensure that the study is ecologically valid, being as similar as possible to actual tutoring conditions at this writing center.

Writers at this center typically either make an appointment or walk in to the writing center. Once there, they fill out an in-take form that indicates their writing concerns, their course number, and some demographic information, including linguistic status. After the in-take form is brought to the back room, the tutor reads over the form and prepares briefly for the session before coming out and meeting the writer. Sessions usually begin with the tutor explaining the forty-five-minute time restriction, the non-directive/non-evaluative methodology of this writing center, and other logistical elements. Then, the sessions proceed.

The sessions were observed at a distance by a researcher while audio of the session was recorded from a digital device on the table. Because the researcher did not influence the type of sessions, the sessions included the natural range of writing genres (e.g., lab reports, personal essays, book reports), mediums (e.g., hard copy of paper, computer, brainstorming with notes), and stages (e.g., exploratory, revision, responding to teacher comments). The sessions lasted between twenty-five minutes up to more than an hour. The researcher, meanwhile, sat out of the line of view of both the participants and took notes on participants’ hand gestures and actions.

After the session, the writers and tutors were asked to fill out a post-session survey about the degree to which the session was non-evaluative, whether they felt there was an emotional connection during the session and whether they felt language impacted the session, and if they felt the writer would have preferred an English-speaking tutor (see Appendix A for complete post-session survey and responses). They were allowed to fill out this survey alone, without the researcher present. Additionally, the survey was administered to tutors and writers separately to avoid any intimidation or social pressure.

After completing the survey, participants were briefly interviewed about how the sessions went and their survey responses. Post-session interviews mostly consisted of elaboration of the survey questions and additional concerns or strengths of the session, especially in terms of language and personality. The interviews were administered away from the main tutoring floor in quiet areas where frank discussion could be unimpeded.

Data Analysis

All 16 sessions were transcribed and then broken into t-units by a research assistant. T-units are described as “the shortest grammatically allowable sentences into which (writing can be split)” (Hunt 1965, p. 21). Looking at t-units instead of sentences allows for complex sentences to be broken into component parts. For example, a tutor might start a sentence describing a solution and then end the sentence with a question to check student understanding. The separate t-units were classified as Affective, Cognitive, or Reading and Chatter with sub-categories adapted from the Melissa M. Patchan et al. (2009) coding scheme for peer review (Figure 1).

Patchan’s coding scheme was used because it had previously captured both affective and cognitive feedback from students to other student writers. Because the peer review conditions described in Patchan et al.’s (2009) study are roughly analogous to writing center sessions, the scheme was considered a good fit to capture similar issues in this study. Additionally, re-using a relevant coding scheme encourages a more unified discussion of peer feedback.

After the initial coding by the author, approximately 10% of the data was coded by a trained graduate assistant to determine inter-rater reliability. The inter-rater reliability was “substantial” (67%) according to the standards of Anthony J. Veira and Joanne M. Garrett (2005).

Results

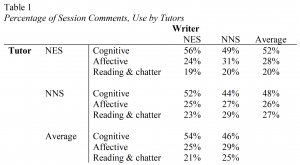

The overall results of the observed sessions indicate that NNS and NES tutors are more similar than different in several important respects. As seen in the rightmost column of Table 1, the average proportions of cognitive and affective language were roughly equal between the NNS and NES tutors. Both groups of tutors spent around half their time making cognitive comments and between a quarter and a third of their time making affective comments. The only meaningful difference in speech between sessions with a NES or NNS tutor was in the least substantial category, Reading and Chatter. But in the main issue—whether NNS tutors use different methods than NES tutors—the overall results seem to indicate more similarity than difference.

However, differences begin to emerge when comparing how both groups work with NNS or NES writers. In the bottom panel of Table 1 are listed the average proportion of the types of comments used with NES or NNS writers. With NES writers, NES and NNS tutors focused primarily on cognitive comments, with affective comments second most common, and then reading and chatter comments. The differences in the types of comments NES and NNS tutors made while working with NES students were not significant (=4.07, p=.13). But the differences were significant with NNS writers (=27.69, p<.0001). With NNS writers, both sets of tutors decreased the amount of cognitive comments, while affective language and chatter increased.

The most dramatic evidence of how NNS writers are treated differently from NES writers is found in both groups’ use of cognitive language. As seen in the lower panel of Table 1, the average percentage of cognitive language is eight percent lower when tutors of both types work with NNS writers.

When working with NNS writers, both groups of tutors changed tactics and also the differences between the groups became more pronounced. The difference in the category of language the two tutor groups used with non-native English students is highly significant (=27.6937 p<.0001). There are a number of ways those differences emerged in the cognitive comments.

Cognitive

Cognitive comments are important for tutoring sessions. Explaining, directing, identifying problems, and situating within the text all contribute to improving writing process and product. When student writers come to a writing center, they expect cognitive support for their writing. As Patchan et al. (2010) demonstrate, criticism (including pointing out problems and recommending solutions) increases when high-ability writers respond to the work of less skilled writers. While affective language receives a lot of attention in writing center studies, cognitive comments are crucial for peer tutoring operations. In the present study, cognitive comments made up the largest sub-section for the observed sessions of both NES and NNS tutors. For both groups, cognitive language accounted for approximately half of all tutor comments (see Table 1).

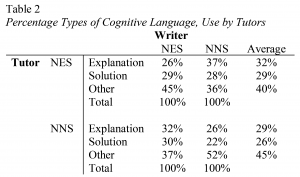

In every session, under every condition, cognitive language was king. Regardless of the tutors’ language background or the language background of their writers, similar patterns emerged among the sub-categories of cognitive language in the sessions. The biggest category of comment in Table 2 is “other,” representing an amalgamation of several small categories (metatutoring, pointing out a problem, localization, and summary) less critical to answering the question of NNS tutors’ directivity. These categories are less relevant for this study than the two biggest single categories: explanation of general writing practices (a non-directive cognitive comment) and offering a solution (a directive cognitive comment).

Both groups of tutors spent, on average, between a quarter to a third of their cognitive comments giving explanations and another quarter to a third offering solutions. As indicated in Table 2, these two categories contributed to a significant percentage of all cognitive comments. There was no statistical difference between the two groups of tutors when working with NES students (=4.70, p=.095), but there was a high statistical difference between the tutors’ use of cognitive language with NNS students (=26.64, p<.0001).

Explanation

The cognitive category demonstrates that both groups of tutors similarly focused on offering solutions and explanations, but differences emerge when looking at the how the tutors in this study used cognitive comments. The two groups of tutors emphasized different sub-categories of cognitive language. NES tutors used significantly less explanation while tutoring other NES writers than they did when tutoring NNS writers. For instance, when tutor Greg[3] (NES) worked with writer Ella (NNS), he explained, “One thing that I think often distinguishes a résumé, like what I would say is a stellar résumé is because it quantifies things.” In this example, it’s easy to see Greg acting as a cultural informant as well as writing tutor as he explains characteristics of the ideal American-style resume. This sentence doesn’t tell Ella that she should quantify her experience, but describes the “stellar” American resume. Greg used many more explanations with Ella. In Greg’s 5,600-word session with her, 25% (95/378) of all of his t-unit comments were explanations, while in his 3,700-word session with Kyle (NES), explanations made up only 6% (13/211) of his comments. Although he spoke twice as much with Ella (NNS), the percentage of explanations increased more than sevenfold. Greg is typical of the NES tutors in our sample, increasing the percentage of explanations in the sessions with NNS writers when compared with NES writers, as indicated in Table 2. Explanation is categorized as a non-directive approach because it focuses the session on general principles of good writing rather than on trying to improve the specific paper at hand, so in this category, NES tutors appear to be less directive with NNS than with NES writers.

When NNS tutors work with NNS writers, overall, these general explanations decrease. When tutor Angelo (NNS) was working with writer Karen (NES), 17% (58/328) of the comments he made were explanatory in his 4,100-word session, including explanations about how to do research, identify different sources, employ parallel structure, and use MLA format; however, when he was working with writer Li-wei (NNS), he gave explanations in only 9% (18/190) of his comments, including three explanations on how to use the writing center’s type of computer. This is roughly half as many explanations as Angelo gave Karen (NES). Angelo is typical of the NNS tutors in this study who decreased their use of explanations when working with NNS writers, while NES tutors like Greg tended to do just the opposite.

Solution

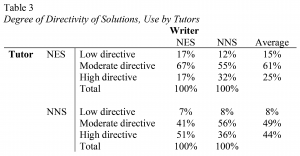

Offering a solution is seen as a more directive move for a writing center tutor. Offering a solution is sometimes considered off-limits in writing center lore, but as Thonus (2004), among others, has shown, some students appreciate a more directive approach. All the tutors in this study gave more solutions than expected, given this writing center’s emphasis on non-directivity in training and in daily practice (see Table 3). Recall that the tutors began these sessions with a verbal explanation of the writing center’s “non-directive, non-evaluative” policy, which served not just to inform the writers, but also to remind the tutors themselves of this particular center’s philosophy. Also, the tables in the tutoring space contain a placard reminding all parties of the center’s stance on directivity, among other policies.

Given such an emphasis on non-directivity, it might be surprising that up to a third of cognitive comments were offering a suggestion (see Table 2). According to Table 2, the NNS tutors were slightly less likely overall to offer solutions than their NES counterparts, and this tendency was more pronounced with NNS writers.

But all solutions are not equally directive. Low-directive solutions are highly hedged, while mid-level solutions may offer minor hedging, and highly directive solutions offer clear imperatives—“change this in this way.” While NNS tutors in this study were less likely than their NES peers to offer solutions overall, the solutions they offered were more likely to be mid- or high-directive solutions (see Table 3, far right panel). Differences in directivity between NES and NNS tutors were significant for NES writers (= 45.14, p<.0001), but not for NNS writers (=1.06, p=.59), perhaps because of the smaller sample of comments in this more selective sub-category. NES tutors were most likely to offer moderately directive solutions, at a rate almost two-thirds of all solutions. The distant second place was for highly directive solutions that explicitly recommended a course of action (around 25% of total solution comments), followed by minimally directive comments.

NNS tutors in this study used, on average, almost twenty percent more highly directive comments than their NES peers (see Table 3, far right panel). Moderate and high directivity combined account for virtually all solutions offered, while minimal direction was very low. NNS tutors in this study were more directive in their solutions than their NES colleagues.

Directivity also depends on who is on the other side of the table. As indicated by Table 3, when NES tutors worked with NES writers, they were most likely to offer moderately directive comments. When working with NNS writers, though, NES tutors used more highly directive language. This increase in directive language between NES tutors and NNS writers didn’t lead to a preponderance of highly directive comments in general; it is just an increase relative to interactions with NES writers. NES tutors were certainly more directive with NNS writers than they were when working with NES writers. This result is in line with the suggestions from their training and writing center conventional wisdom that claims that when working with NNS writers, the NES tutors should become more directive.

However, when the NNS tutors in this study worked with NNS writers, the degree of high directivity, while still very large, decreased. The NNS tutors in this study had all been trained in conventional wisdom that directivity with NNS writers is desirable, yet the NNS tutors were less directive with NNS writers than they were with NES writers. A clue to why this happened appears in the interviews conducted before the observations. Many of the NNS tutor interviewees reported that they felt that standard non-directive writing center practice applied equally to NES and NNS writers. Angelo (NNS), while one of the most directive of the NNS tutors in practice, reported in his interview that he had recently been successful when applying non-directive, non-evaluative methods with a NNS writer. And Sarita (NNS) said:

Initially I was wondering how useful the non-directive approach was for someone who doesn’t have English as a native language, […] But now I realize that ultimately what’s important for them is to learn, right? And to be able to write on their own without any help at all.

It’s possible that while working with NNS writers, these tutors were more conscious of their commitment to non-directive tutoring.

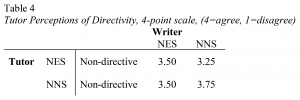

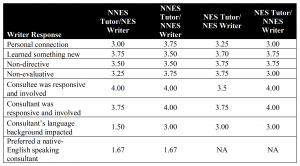

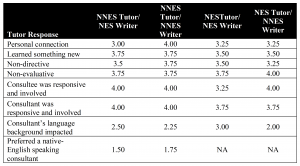

The opposite is also true, though: NNS tutors were most likely to be highly directive when they were offering solutions to NES writers. NNS tutors’ practice of directivity is at odds with the perceptions of directivity as expressed in both interviews and in the post-session surveys (see Table 4). In the interviews conducted well before the sessions, one NNS tutor said, “I think for [tutoring], the non-directive approach, no matter how hard it seems in the beginning, is the only approach.” While the actual degree of directivity was higher in observed sessions with NNS tutors than with NES tutors, the NNS tutors ranked themselves as equally non-directive as the NES tutors on a four-point scale administered immediately after the session (see Table 4). NES tutors, meanwhile, believed that they were more directive with NNS writers than with NESs, matching the observed sessions.

Affective

For Grimm (2009) and Canagarajah (2006), NNS tutors’ experiences exemplify principles of academic code shifting and shuttling among languages, and also provide points of empathy and understanding for NNS writers. In an interview conducted immediately after the session, one NNS writer said that while she would prefer a NES tutor for questions of language accuracy, “sometimes I feel like a native English speaker actually doesn’t know a lot about our international students’ heart,” and that native English-speaking tutors don’t understand how an English learner approaches the language. Similarly, after a session with tutor Pedro (NNS), writer Magdalena (NNS) said, “I think it’s good to have someone who knows your problem […] especially when you talk about if you had a connection” with the tutor. The NNS tutors echo these claims, stating that they were able to better empathize with their NNS writers. Tutor Miles (NNS) said, “I think that it does help [NNS writers] to see that someone who had this other culture that’s often the same as theirs could have this mastery of the language, maybe it’s an encouragement to them.” But while perceptions highlight the emotional connection between NNS tutors and writers, the data tell a different story.

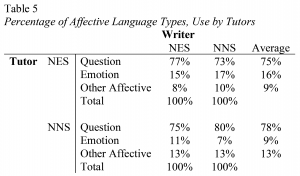

Although NES and NNS tutors did not significantly differ (=4.71, p=.09) in their use of affective language for NES writers, both groups changed their use of affective language with NNS writers, and in significantly different ways (= 12.35, p<.01). When NES tutors worked with NNS writers, they significantly increased their use of affective language as a proportion of their overall comments; when NNS tutors worked with NNS writers, affective language did not increase (Table 1). The NES tutors made more affective comments than the NNS tutors when working with NNS writers (see Table 5). This is rather surprising when read in the light of NNS tutors’ perceptions described above; instead of NNS tutors connecting through affective language to the NNS writers, the NES tutors were, on average, more affective in the comments that they made. The breakdown of sub-categories categories within the affective comment category demonstrates additional surprising differences between the two groups of tutors.

According to Table 5, on average, the two groups of tutors were relatively similar in patterns of questions and the other affective category (a collapsed category comprising praise and mitigating comments), but the NES tutors used almost twice as much language signifying emotional states as their NNS colleagues. Not only were the NNS tutors using less emotional language on average, but that average is driven down largely because of a marked decrease in emotional language when the NNS tutors in our sample worked with other non-native speakers of English. NES tutors used three-quarters of their affective language asking questions of their writers. When NES tutors worked with other native English speakers, they used slightly more questioning and less praise than they did when they worked with NNS writers.

Like their NES colleagues, NNS tutors used around three-quarters of their affective language for asking questions. Emotion accounted for only around ten percent of NNS tutors’ affective language. When NNS tutors worked with NES writers, they were less likely to ask questions than they were when working with NNS writers; this is the opposite pattern as seen with NES tutors, and to the same degree—around five percentage points.

Questions

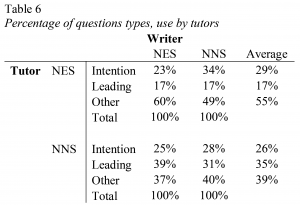

The largest affective language sub-category was questioning language (see Table 5). While both groups relied heavily on asking questions when they used affective language, the types of questions varied across the two groups of tutors. The statistical significance of the difference for the tutor groups was quite high, both for NES students (= 24.69, p<.0001) and for NNS students (=12.18, p<.01).

For addressing the NNS tutors’ degree of directivity, the most important questioning sub-categories are intentional and leading questions, respectively[4]: questions that focus on the writer’s intention or internal state (generally seen as non-directive) and questions that lead the writer to an evaluation or solution (generally seen as directive) (See Table 6). These two categories are the most useful for looking at whether NNS tutors are, in fact, more directive and also whether they are more emotionally responsive than NES tutors when working with NNS writers.

When NES tutors worked with NES writers, around a quarter of their questions were focused on writer intent, but when they worked with NNS writers, NES tutors asked significantly more intention questions. Again, the NES tutors appeared to be increasing their emotional response to NNS writers, not only through a high use of emotional language as seen in Table 5, but also through an increase of those questions that relate to internal and subjective conditions. NES tutors may make a specific effort to be more sensitive to the emotional status of NNS writers, possibly because writing center training and scholarship has emphasized NNS writers as a vulnerable student population.

For NNS tutors in this study, leading questions were more common than intention-based questions (Table 6). On average, 35% of NNS tutors’ questions were leading, while leading questions made up only 17% of NES tutors’ total questions. When they asked questions, the NNS tutors in this study used almost twice the percentage of leading questions overall. The NNS tutors were more directive in pointing out solutions and they were more directive in asking leading questions. The relatively high amount of leading questions corresponds reasonably with the results found in Table 3 about NNS tutors’ relatively high degree of directivity.

There was also a difference in how the two groups of tutors used questions with NES or NNS writers. The NNS tutors used significantly more leading questions in total, but while NES tutors increased the number of leading questions by nine percentage points with NNS writers, NNS tutors increased intentional questions by only three percent with NNS writers. When the NNS tutors worked with NES writers, they used more leading questions than when they worked with NNS writers. Both NNS and NES tutors appear to have increased non-directive questions about their writers’ intent, but the effect was stronger among NES tutors. Still, it’s also interesting to note that while NNS tutors in the sample were, on average, more directive and asked more leading questions than their NES peers, they made a sharp eight percent decrease in leading questions when they worked with NNS writers. This seems to indicate that when working with NNS writers, NNS tutors were less directive than usual and were slightly more emotionally responsive in their questions.

Perceptions of native-speaker fallacy

NNS tutors in this study tend to be, on average, more directive than their NES colleagues, and since that directivity tends to be increased with NES writers rather than NNS writers, it is possible that NNS tutors increased their directivity in response to their perception of bias against them. Sandrine (NNS) suggested this in her interview when she said:

I don’t know if this is me being self-conscious, but you always have the impression that you have to do more to show that you’re competent, that [you’re] qualified to talk English with [a writer] when English isn’t even [your] second language.

This attitude demonstrates a self-consciousness in the face of the native speaker fallacy—the NNS tutors have to “do more” to prove their language skills. When Chang (2011) found strong evidence of the native-speaker fallacy among the writers at her participant institution, she also found that the NNS tutors were aware of the prejudice against them. Donald L. Rubin and Kim A. Smith (1990) found that forty percent of the undergraduates in their study avoided NNS TAs’ classes. Such an atmosphere may express itself in the overall high level of directivity in NNS tutors’ sessions, and especially with NES writers, as they seek to establish their authority.

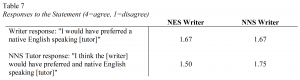

However, most of the participants in this study self-report low influence of the native speaker fallacy. The participants in the current study, both tutors and writers, did not report language discrimination in this writing center. All of the interviewed NNS tutors said that they felt comfortable and competent among their NES colleagues, and, with the exception of Sandrine, most of the NNS tutors said they had positive or neutral experiences when working with writers. Overall, NNS tutors didn’t perceive language discrimination from their writers. This perception is in line with the post-session survey information collected in this study (see Table 7). When NNS tutors were asked to respond whether the student in the session would have preferred a native-speaking tutor, on a 4-point survey (4= “I would have preferred a native English speaking [tutor]”), average responses were quite low for both their NES and NNS writers—1.5 and 1.75 respectively. There was an increase when NNS tutors imagined whether NNS writers would have preferred a native English speaker. Writers of both groups were unlikely to indicate a preference for a NES tutor: both NES and NNS writers ranked a preference for a NES tutor as 1.67 on average on a 4-point scale.

This perceived comfort with NNS tutors in the writing center doesn’t disprove Chang’s (2011) early findings. It may, perhaps, be caused by the relatively large numbers of NNS tutors at our participant institution or because of differences in student populations at the two institutions in the case of Chang’s (2011) study. In contrast, the present study with its particular participants found that NNS tutors were not avoided, demonstrating low prevalence of the native speaker fallacy.

Limitations and Further Research

While the results of this study can shed light on how a group of NNS tutors at a particular writing center operates, the usual cautions about generalization must be applied.

First off, writing centers as a whole may have a different milieu than formal classrooms when it comes to the native speaker fallacy and other linguistic biases. Possibly, student expectations of a writing tutor aren’t the same as that of an instructor leading a class: instead of being positioned as authorities, writing center tutors are described as peer experts, with an emphasis on the “peer.” While Canagarajah (2006) and Rubin and Smith (1990) were looking at bias against NNS instructors, the positionality of the tutor in the writing center may diffuse authority concerns.

There can also be a distinct culture at each writing center, especially one that traditionally employs a high number of NNS tutors. With more NNS mentors and colleagues, NNS tutors may have different attitudes and practices than those NNS tutors who work as an extreme minority in centers predominantly staffed with native English-speakers. A large writing center that employs around 10 NNS tutors is a remarkable resource for looking at a population that sometimes shows up in ones and twos in most writing centers; but having such a critical mass of NNS tutors may influence perceptions of NNS tutors among the writing center staff at large, as well as with student writers. Language background of tutors wasn’t the only local condition of this writing center. Additionally, this writing center was strongly committed to making certain that tutors and writers both were aware of its non-directive, non-evaluative, and emotionally responsive philosophy. Through training and verbal and visual reminders, tutors and writers were drilled in the benefits of non-directivity. A large, research institution writing center that serves thousands of students a year will have its own culture and practices that may not transfer to other institutions.

Additionally, although the size of the writing center in this study meant that there were more NNS tutors to observe than in Chang’s (2011) study, there can still be a large degree of variance in looking at four tutors’ sessions. The NNS tutor participants in this study were individuals with individual tutoring styles.

For instance, during this study, one writer, Sue (NNS), worked with tutors from both groups— Eric (NES) and Miles (NNS). Miles was a much quieter, more introverted tutor than Eric. When Sue worked with Miles (NNS), he spoke half as much as Eric (NES) did when he worked with her (2,329 words compared to Eric’s 4,448). Exceptions based on personality can emerge. For example, while NNS tutors in this study were, on average, less directive than their NES colleagues when working with NNS writers, the range between Miles and Eric was very large: when Sue worked with Miles (NNS), only six percent (13/206) of Miles’ comments were solutions, but with Eric (NES), solutions made up sixteen percent (47/293) of his comments. Many other factors could contribute to Miles’ individual tutoring style besides his linguistic background, such as his younger age and undergraduate status compared to Eric the graduate student. Looking at the composite average of all sessions of all participant tutors provides more generalizable conclusions, but scholars must acknowledge that sessions, like individuals, are complex and involve far more factors than any combination of studies could hope to tease out. A more robust study could include a multi-institution study of NNS tutors with a larger number of participants. Since NNS tutors are almost always an extreme minority at writing centers, including more institutions will create a larger pool of participants. Including more participants will dilute the impact of individual personality traits and tutoring strategies.

Further studies could also investigate how the prevalence of NNS tutors and teachers at an institution has an impact on the degree to which those tutors and teachers are avoided. The same could be asked about the prevalence of NNS students enrolled at the institution: does a more diverse student body result in less discrimination against multilingual teachers and tutors? Also, if there are indications that native speaker fallacy is prevalent in an institution, what training practices can counteract those attitudes? If Thonus (2004) suggests “training” (p. 240) writers in how to work in a traditional writing center, how might that training look if NNS tutors are included?

Conclusions

NNS tutors appear to be very similar to NES tutors in many of their tutoring strategies: Both groups of tutors make primarily cognitive statements in sessions with both NES and NNS writers; both groups ask many questions of their writers and both groups decreased the percentage of cognitive statements when working with NNS writers. Whether such characteristics are desirable in sessions is beyond the scope of this study and should be addressed according to individual writing centers’ objectives. For instance, if we believe that NNS writers need more concrete examples and solutions, as Jessica Williams (2004), Susan Blau et al. (2001), and other writing center scholars suggest, then training might need to re-emphasize the role of cognitive statements like explanations and solutions when working with NNS writers.

At the same time, training depends on what an individual writing center chooses to prioritize. If non-directivity is highly valued in a writing center, additional examples of non-directive language and sample non-directive sessions might be necessary to help NNS tutors get a sense of what non-directivity looks like in practice. Recall that in the interviews surveys conducted after each session, the NNS tutors in this study perceived themselves as being very non-directive, even with NNS writers. Still, NNS tutors were more likely, on average, to offer highly directive solutions and were more likely to ask leading questions than were their NES colleagues, especially when working with NES students. Their perception of what amount of directivity is still generally “non-directive” may be different than NES tutors’ perceptions.

One possible explanation of this disconnect is that the NNS tutors saw themselves as being less directive in comparison to their previous experiences with learning to write. As Chang (2011) points out, many NNS writing center tutors come from backgrounds where teachers are expected to be authoritarian and students are expected to be passive and deferential. As Sarita (NNS), pointed out:

Back home [in India] it’s different because the teacher has a position of greater authority and power whereas in the U.S. it’s more egalitarian. […] We have this long tradition of respecting the teacher or revering the teacher almost and that doesn’t exist here. [At the writing center,] I needed to see that we need to be friendly with our [writers] rather than speak to them from a position of authority.

If NNS tutors see non-directivity as a relative (rather than absolute) quality, a writing center emphasizing non-directivity could provide explicit examples and models to tutors from other teaching cultures. Tutors Sarita (NNS) and Damini (NNS) pointed out that videos and sample sessions during training helped them to see that there were cultural differences between the Indian educational traditions they grew up with and the non-directive, non-evaluative culture of this particular American writing center. For writing centers that want to encourage a certain level of directivity, providing all tutors with such examples can make “non-directive” less of an abstract value than a series of strategies to be used in actual sessions. Providing all tutors with a less culturally dependent view of what non-directivity looks like in practice can potentially help everyone who tutors, but may be especially worthwhile for tutors coming from more hierarchical pedagogies.

Culture also impacts NES tutors engaging with NNS writers. NES tutors who have been trained to think of NNS writers as an exception or as an at-risk group may treat them differently because they see NNS as “different.” The native English speaking privilege of these tutors may be more on display when they work with NNS writers. It’s hard to know what is the “right” amount of emotionally responsive or non-directive language for any tutor to use, but emphasizing different rules with different language backgrounds complicated those general issues of traditional writing center pedagogy. When NES tutors use more affective language with NNS writers and ask a higher percentage of questions about writer intent, is this because they are responding to the many anxieties that often plague someone asked to write academically in another language and culture? Or are they just handling writers who are “different” with kid gloves? The NES tutors participating in this study were thoughtful, sensitive tutors, but even they might not be able to pin down their exact motives. Alternately, it may be clear that the NNS tutors in this study used far less emotion-based language and fewer intent-based questions when they worked with NNS writers, but it’s impossible to say whether that occurred because NNS tutors felt they didn’t have to be as “careful” with NNS writers because they took their emotional connection for granted, or because they didn’t want to be found showing favoritism to those who were, in some way, similar to them. It’s not clear whether writing centers should aspire to give NNS writers additional emotional support or should try to treat them “like everyone else.” Wise writing center directors will always encourage their tutors to think of their writers as individuals who are probably all dealing with varying degrees of discomfort and culture shock.

This study does, however, encourage writing center directors and researchers to continue to think of their tutors in non-stereotypical ways. NNS tutors as a whole may have different characteristics than NES tutors as a whole, but even the term NNS tutor creates a false binary. This study included tutors who had studied English since grade school and tutors for whom English was not just a second language, but a third or fourth. They had language backgrounds as diverse as they were diverse individuals. Still, in doing this research I have been impressed with the professionalism and concern for students that I felt from all of participants, NNS and NES tutors alike. They represent the future of the discipline. In fact, since completing the data collection portion of this study, one of the NNS participants has become, as far as I can tell, one of the very few NNS writing center directors at a large American university. It is increasingly obvious that non-native English speakers are not the other in our writing centers—they are us.

Appendix A

Post-session survey (Note: in this writing center, tutors are called consultants and writers are called consultees.)

Writer and tutor perception, post-session session

Funding

The author received a grant from the International Writing Center Association for transcription services and inter-rater coding of this study.

References

Barwashi, A., & Pelkowski, S. (1999). Postcolonialism and the idea of a writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 19(2), 41-59.

Blau, S., Hall, J., & Sparks, S. (2002). Guilt-free tutoring: Rethinking how we tutor non-native-speaking students. The Writing Center Journal, 23(1), 23-44.

Blau, S., Hall, J., Davis J., & Gravitz, L. (2001). Tutoring ESL students: A different kind of session. Writing Lab Newsletter, 25(10), 1-4.

Brooks, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. Writing Lab Newsletter, 15(6), 1-4.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Interrogating the “native speaker fallacy”: Non-linguistic roots, non-pedagogical results. In G. Braine (Ed.), Non-native educators in English language teaching (pp. 77-92). NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2006). Towards a writing pedagogy of shuttling between languages: Learning from multilingual writers. College English, 68(6), 589-604.

Chang, T. S. (2011). The relationality between ‘self’ and ‘other’: Native and non-native English speaking tutors’ roles in the writing center (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois, Carbondale.

Choudaha, R., & Chang, L. (2012). Trends in international student mobility. World Education News and Reviews. Retrieved from http://wenr.wes.org/2012/02/wenr-february-2012-trends-in-international-student-mobility

Cogie, J., Strain, K., & Lorinskas, S. (1999). Avoiding the proofreading trap: The value of the error correction process. The Writing Center Journal, 19(2), 7-32.

Grimm, N. (2009). New conceptual frameworks for writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 29(2), 11-27.

Hunt, K. (1965). Grammatical structures written at three grade levels (Report No. 3). Champaign, IL.: National Council of Teachers of English.

Gillespie, P., & Lerner, N. (2008). The Longman guide to peer tutoring (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

Murphy, C., & Sherwood, S. (Eds.) (2011).The St. Martin’s sourcebook for writing tutors (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University Press.

Myers, S. A. (2003). Reassessing the “proofreading trap”: ESL tutoring and writing instruction. Writing Center Journal, 24(1), 51-70.

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446.

Patchan, M. M., Charney, D., & Schunn, C. D. (2009). A validation study of students’ end comments: Comparing comments by students, a writing instructor, and a content instructor. Journal of Writing Research, 1(2), 124-152.

Patchan, M. M., Hawk, B., Stevens, C. A., & Schunn, C. D. (2010). The effects of skill diversity on commenting and revisions. Instructional Science, 1-25.

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Rafoth, B. A. (2015). Multilingual writers and writing centers. Logan, UT: Utah State Press.

Redden, E. (2018, Jan 22). “International student numbers decline.” Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/01/22/nsf-report-documents-declines-international-enrollments-after-years-growth

Reynolds, D. W. (2009). One on one with second language writers: A guide for writing tutors, teachers, and consultants. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Rubin, D. L., & Smith, K. A. (1990). Effects of accent, ethnicity and lecture topic on undergraduates’ perceptions of nonnative English-speaking teaching assistants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations (14)3, 337-353.

Ryan, L. & Zimmerelli L.(2016). The Bedford guide for writing tutors. (6th ed.) Boston : Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Shamoon, L. K., & Burns, D. H. (1995). A critique of pure tutoring. The Writing Center Journal, 15(2), 134-151.

Thonus, T. (2004). What are the differences?: Tutor interactions with first-and second-language writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(3), 227-242.

Williams, J. (2004). Tutoring and revision: Second language writers in the writing center. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(3), 173-201.

Wong, A. (2018, Jun 28). “Should America’s universities stop taking so many international students?” Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2018/06/international-students/563942/

Notes

- Non-directivity is a complex concept that is in transition. There are writing centers moving away from the strict definitions of non-directivity described in the foundational writing center texts. The purpose of this paper is not to suggest that some degree of directivity is ideal, but to describe how directivity is discussed and implemented by practitioners. In this sense, my discussion of directivity is descriptive, rather than prescriptive. ↑

- Like “non-directivity” the term “emotionally responsive” or “empathic” are less clearly defined than generally invoked in some of these core writing center texts. Also, like non-directivity, there are many theoretical concerns about asking student tutors to do the care labor of being “emotionally responsive.” Again, my use of this term is more to highlight how it is invoked in the general practice rather than to prescribe any ideal of empathy. ↑

- The name, and all the names of tutors and writers are pseudonyms chosen to match the culture of the participant’s original first name. For example, if the original name of a participant from Russia was Anya, she might be referred to as Nadiya. If, however, she went by Annie, she might be referred to as Emily. ↑

- The “other” category of question in Table 6 is very large, but this catch-all category of technical and metatutoring questions is not as relevant to the current study. ↑