Grant Eckstein

Abstract

Writers for whom English is a second language (L2) are thought to benefit from tutors who function in an informant role in which they provide cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information that L2 writers sometimes lack. While this approach is intuitively satisfying because L2 writers may have gaps in their schematic knowledge of English or related rhetoric and culture, researchers have yet to ask students whether they want informant-tutors or to compare student preferences across language backgrounds. In this study, I operationalized three types of information tutors might supply: rhetorical, cultural, and linguistic. Students from across the U.S. (N=200) who had recently attended a writing tutorial completed a survey asking them to rate the relative importance of several sub-skills within each informant category. The students were further categorized as L1, L2, or Generation 1.5 writers based on responses to an extensive demographic section. Results show that all groups felt it was important for tutors to be informants with almost no significant variation across language groups. These findings emphasize that all writers want academic information and suggest that tutors should provide this irrespective of a student’s language background.

Keywords: L2; Generation 1.5; Rhetorical; Cultural; Linguistic; Informant; Writing Center

Introduction

This article investigates the degree to which writers with different linguistic backgrounds differ in their perceptions of what cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information tutors should provide in U.S.-based writing tutorials. The reason for investigating this issue stems from recommendations by writing center experts who began to rethink the way tutors should interact with second language (L2) writers in the early 1990s. Traditionally, writing centers had encouraged minimalist or non-directive tutoring (Brooks, 1991; Clark, 2001; Shamoon & Burns, 2008). Clark (2001) explained that in its most traditional interpretation, a non-directive tutorial approach is “one in which the tutor intervenes as little as possible” (p. 33) lest the tutor engage in illegitimate collaboration that leads, she argued as part of a book-length treatment, to “tutor dominated conferences” that, “instead of producing autonomous student writers, usually produce students who remain totally dependent upon the teacher or tutor, unlikely ever to assume responsibility for their own writing” (Clark, 1985, p. 41). Brooks (1991) further argued that tutors who provide direction on student writing may improve the paper but fail to tutor the student, thus contravening the purpose of a writing center. He recommended that tutors use leading questions instead of directive comments (e.g. “Can you show me your thesis?” instead of “You don’t have a thesis.”) so that the student provides the rationale for making revisions rather than the tutor (Brooks, 1991, p. 4). Numerous other writing center professionals have drawn parallels between non-directive, leading tutorials and the Socratic method in which tutors engage in question-answer dialectics until the writer arrives at a stronger understanding of their work (Brown, 2010; Jaegar, 2016; Thomspon, 1999). It should be noted, though, that subsequent writers, such as Shamoon and Burns (2008) and even Clark (2001) criticized extreme minimalist/non-directive views of tutoring and recommended alternative or hybrid approaches.

One particular alternative designed specifically for L2 writers came from Powers (1993). She advocated for more directive tutoring for L2 writers by suggesting that tutors could take on an informant role (not just collaborator or coach) in order to provide cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information that students lacked. Other researchers investigating or advocating for L2 writing center practices have similarly agreed over the years (Blau, Hall, Davis, & Gravitz, 2001; Reid & Powers, 1993; Staben & Nordhaus, 2009; Thompson, et al., 2009; Thonus, 1998; Tseng, 2009; Weigle & Nelson, 2004; Williams, 2004). For instance, Thonus (1998) and David (2009) have encouraged more directive tutoring for L2 writers, and Blau, Hall, and Strauss (1998) have recommended caution when using the Socratic Method, suggesting that non-directive tutoring is better suited for process issues, such as when dealing with ideas, organization, and the student’s voice, but that directive feedback is better for content issues such as grammar and mechanics since these have formal rules associated with them.

Thanks to continued interest in L2 tutoring scenarios, the advice of tutors to serve as cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic informants remains an active approach to working with L2 writers (Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Staben & Nordhaus, 2009). More importantly, this advice appears to be something that writing center researchers have recommended for L2 writers alone, not native-English (L1) students. Presumably, this is because L1 writers already possess cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic knowledge whereas L2 writers are at an obvious disadvantage (Staben & Nordhaus, 2009). Questions remain whether, and to what extent, writers themselves want tutors to be cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic informants. These preferences may further differ based on whether a writer is a native-English speaker with presumed expertise in cultural knowledge, an international student with limited exposure to the dominant culture, or a Generation 1.5 (Gen 1.5)[1] student with varying levels of cultural and rhetorical knowledge. The rationale for supplementing L2 writers’ background knowledge comes from theories of cognitive psychology and language acquisition, which both draw on schema theory in order to describe the effect that a student’s prior knowledge or experience in the world has on language learning.

Schema Theory

The notion of schema was made popular by Bartlett (1932) when he described a schema as a mental organization of past reactions or experiences that help a learner interpret their observations of the world (see also Wagoner, 2013). Cognitive psychologists since Bartlett have elaborated on his description, and now a schema is thought of as a cognitive framework created out of prior experience, observation, or learning, that allows an individual to interpret or organize information in their mind (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Carrell, 1983; Mandler, 1984; Rumelhart, 1980). For example, a person may develop a schema for a conversation by which they expect that a conversation will include a greeting, some form of asking and answering questions, a closing of the conversation, and leave-taking. Conversations which conform to this schema are easier for interlocutors to interpret and understand than conversations which do not. Moreover, conversation analysts and pragmatics scholars have identified numerous features of conversation such as greeting, turn-taking, apologizing, and leave-taking (Blum-Kulka, House, & Kasper, 1989; Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1974) that follow relatively systematic and predictable forms and are usually culturally- or linguistically-specific (Scollon, Scollon, & Jones, 2011). Performing conversational roles in a second language can be especially complex (Cohen & Olshtain, 1993) and therefore may warrant the assistance of a linguistic guide or informant.

Additionally, schemata can also refer to observations and experiences involving cultural norms and references, and this can in turn affect a student’s ability to comprehend a text (Steffensen, Joag-dev, & Anderson, 1979). For instance, a recent immigrant to the U.S. with little exposure to American politics may struggle to understand a text which refers repeatedly to the American political system; whereas, a student from the U.S. who has cultural familiarity with American politics should find the text comparatively easy to understand.

Carrell and Eisterhold (1983) explained that it is essential for students to activate appropriate schematic knowledge in order to efficiently comprehend what they read. They further posited three types of schemata that can affect reading comprehension: formal, content, and linguistic. Their definition of formal schemata refers to prior knowledge about rhetorical and generic structures of a text, while content schemata refers to background knowledge of the topic at hand, and linguistic schemata refers to knowledge of and about language (Carrell and Eisterhold, 1983). Theoretically, any learning environment can be enhanced by activating a student’s prior knowledge or experience related to the learning task or the content of the task.

A unified schema theory predicts that a student’s comprehension of text will increase in relation to schematic awareness and diminish if one or more of the three schemata types listed above are missing. Carrell and Eisterhold (1983) emphasized that this is particularly true for students learning a second language since they are less likely than L1 students to have developed linguistic schemata and possibly background knowledge about cultural references that would otherwise make it easier to interpret a text.

Reid and Powers (1993) applied this notion of schemata to L2 writers. They explained that when L2 writers have complete formal, content, and linguistic schemata, then their writing task is relatively easy; however, with some or all schemata missing, the task of comprehending relevant texts and communicating information to others becomes much more complicated. They noted these insights in their writing tutorial program at the University of Wyoming in which tutors met with three or four L2 writers each on a weekly basis throughout a semester of writing instruction to engage in collaborative writing development. Whereas tutors had originally been instructed to use Socratic questions and non-directive intervention to help students think through their writing problems and form personalized solutions, the researchers found that this approach only worked for students who possessed “a lifetime of exposure to the experiences, rhetorical structures, and vocabulary of writing in English” (Reid & Powers, 1993, p. 26). L2 writers were often confused and frustrated by tutor requests to hypothesize about audience, purpose, or logic in a writing assignment because these requests elicited schematic knowledge which the students did not possess. To resolve this, Reid and Powers (1993) instructed their tutors to become cultural informants and facilitators “in order to assist students to identify appropriate linguistic, contextual, and rhetorical schemata” (p. 27). In other words, tutors were encouraged to explain cultural references or grammatical structures to their writers. This is the origin of and rationale for the injunction now common in L2 writing center research and training guides for tutors to take on an informant role when working with L2 writers (Babcock & Thonus, 2012; Blau, Hall, Davis, & Gravitz, 2001; Blau, Hall, & Sparks, 2002; Powers, 1993; Staben & Nordhaus, 2009; Weigle & Nelson, 2004).

Ostensibly, the application of schema theory implies that L1 writers do not need schematic information during a writing tutorial because they already have intuitive knowledge about culture, rhetoric, and language used in academic writing. While this may be true, I wanted to determine if writers differed in their perceptions of what information they felt tutors should provide in writing tutorials based on language background. I hypothesized that, based on Reid and Powers’ (1993) observations of schemata noted above, L2 writers in a writing center context would report a stronger preference for cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information than L1 writers. I also expected that Gen 1.5 writers would situate in the middle of L1 and L2 writers by reporting a strong desire for linguistic information but not culture or rhetoric based on Reid’s (1998) observation that Gen 1.5 writers tend to have exposure to American culture and rhetorical conventions of academic writing in their U.S. schooling. I used the following research question to investigate the issue of tutor-informant roles: To what degree do L1, L2, and Gen 1.5 writers feel that writing tutors should address issues of cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic knowledge?

Methods

I chose to use a survey-based, quantitative approach to measure different preferences for tutor informant roles among writer groups. Such an approach diverges from writing center research that has documented the content of writing tutorials in line with North’s (1984) injunction for the writing center to “prove its worth” through a description of tutorial talk (p. 444). Nevertheless, other writing center research has used a variety of inquiry approaches such as action research, ethnographies, discourse analyses, case studies, and survey data collection (Babcock & Thonus, 2012). Survey-based investigations are particularly thought of as “time honored methods” in writing center research and assessment (Bell, 2000, p. 9) because survey data can be systematic and standardized while requiring relatively little time and resources to collect. It is also easier to collect a large, geographically-diverse sample through survey data, something that is nearly impossible through more qualitative approaches. Since this study was meant to compare a large sample of students and their self-perceptions on a range of specific informant roles, a survey with closed-ended responses was deemed the most effective approach for data collection and analysis. In the sections below, I outline the survey design, distribution, and data analysis that inform this study.

Data Collection Instrument

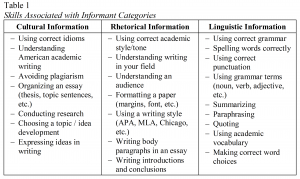

In order to collect information about students’ perceptions of what cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information should be shared in a writing center tutorial, I first created an inventory of writing skills where each skill fell into one of the three broad categories of cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic intervention (see Table 1). The inventory was neither exhaustive nor authoritative as I created it myself, operationalizing my own experience and intuition as an L2 writing instructor and tutor. This is because, as Staben and Nordhaus (2009) pointed out, writing specialists have yet to clarify precisely what it means to provide cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information to L2 writers despite the fact that it has been more than two decades since Powers (1993) advised tutors to be informants to L2 writers. Thus, I was obliged to construct my own inventory of skills. Unfortunately, an inventory like this makes it appear that these skills belong to only one category, which is inherently problematic. For instance, I placed the item spelling words correctly in the Linguistic Information category where it seems to fit best, yet there are instances where a word’s spelling is a matter of cultural and rhetorical choice, such as using British spelling, spelling a word phonetically, or transliterating a word from another language. In each of these cases, a tutor could engage in a conversation with a writer about the cultural appropriateness of the chosen spelling and/or the rhetorical effect such a spelling might have.

The fact that so many elements of writing could arguably fit in all three information categories may be the very reason writing center specialists have not developed an authoritative inventory of skills. Moreover, it is beyond the scope of this study to create an exhaustive list of all writing topics that tutors could possibly address, so I limited my inventory to a manageable number of topics. Thus the inventory I have assembled is based solely on my own experiences, interpretations, and impressions and may serve as a starting point for further classification (or reclassification) of informant sub-skills.

Procedure

After developing this inventory, I created a survey (see Appendix A) asking participants to rate the relative importance of each sub-skill on a scale from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). I used the following statement to solicit their responses: “Writing center tutors are not always able to address all aspects of writing in a single visit. So of the topics and skills listed below, which do you think are the most important for tutors to help with?” The survey listed sub-skills in random order rather than grouping them by informant role, which meant that respondents were unaware of the informant role classifications. Each sub-skill was listed concisely without definition or elaboration. Participants rated each sub-skill individually rather than rank-ordering them all.

I also included an extensive demographic component so that I could use participants’ responses to categorize them as L1, L2, and Gen 1.5 writers. L1 writers were so classified based on their self-reported native-English speaking background, their exclusive use of English to communicate while growing up, and their (and their parents’) birthplace in the U.S. or another English-speaking country (e.g., Australia, Canada, and England). Participants with bilingual upbringing or for whom English was a second or additional language were not classified in this category. Instead, I classified L2 writers as those who were international, visa-holding students from countries other than Australia, Canada, and England (unless they had a non-English L1 such as French) and who had also lived in the U.S. for less than 5 years and had graduated high school outside of the U.S. Thus the L2 writers might be better described as international L2 writers since they had to be both international students and L2 speakers to qualify for this group. The Gen 1.5 group was composed of writers with various backgrounds reflecting Ferris and Hedgcock’s (2014) characteristics of Generation 1.5 learners. This group consisted of individuals who spoke a language other than English natively (beyond merely studying a second language in high school), had immigrated to the U.S. or were children of immigrants, had lived in the U.S. for 5 or more years, and had graduated high school in the U.S. (Ferris & Hedgcock, 2014).

In order to collect responses from a wide group of writers with recent writing center experience, I digitized the survey and distributed it as part of a larger, national survey of writing center visitors (Eckstein, 2016). I contacted more than 800 writing center directors based on information collected from the International Writing Center Association contact list (http://web.stcloudstate.edu/writeplace/wcd/cUSA.html) and also distributed it to directors I was familiar with at schools with high international student populations. The survey link remained active for seven months during the 2012-2013 academic year.

Participants

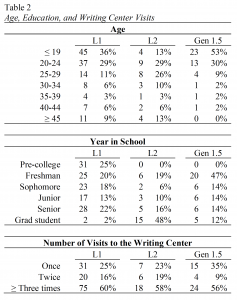

In total, 200 participants responded, which, broken down by language background, equated to 126 (63%) L1 writers, 31 (16%) L2 writers, and 43 (22%) Gen 1.5 writers (see Table 2 for additional demographic information).

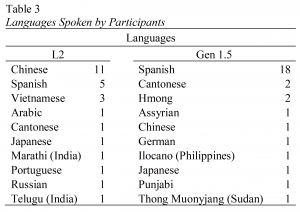

Of the L2 writers, 10 different native languages were represented, almost all of which were Asian. The Gen 1.5 group also represented 10 different languages, of which the majority spoke Spanish (see Table 3 for more details). Additionally, L2 writers were older on average than L1 or Gen 1.5 writers.

Nearly half of L2 writers were also graduate students while an almost identical proportion of Gen 1.5 writers were freshmen. Unfortunately, because of institutional approval limitations, I was not able to link student responses to individuals or even to individual schools, and I did not ask where students resided, all of which prevented me from calculating a geographical distribution of participants, though writing center directors who actively distributed the survey link reflected 26 different U.S. states.

Analysis

My primary objective in this study was to determine if the three language groups differed in statistically significant ways from one another in terms of their perceptions of what cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information should be shared in a writing center tutorial. My expectation was that L2 writers would express the strongest desire for this information.

In order to answer the research question, participant responses were converted into numerical scores, which were then analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, which compares three or more groups to determine if there are significant differences among them. The language group was the independent variable and the agreement score for each sub-skill in the cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information categories was the dependent variable. In addition to reporting mean ranks, which is standard for the Kruskal-Wallis test, I deviated from convention by also including descriptive mean scores to further explicate the data. Significant items were further analyzed using post-hoc pairwise comparisons to determine precisely how the three language groups differed and a Bonferroni adjusted alpha of .0167 (.05/3) to account for the multiple comparisons which otherwise might lead to an overestimation of differences.

Results and Discussion

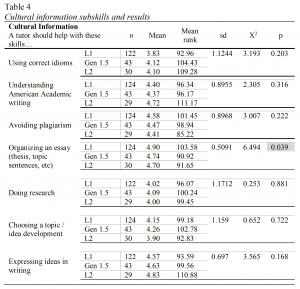

Overall, the results of the Kruskal-Wallis test showed almost no significant difference among the three language groups in terms of what information they felt tutors should provide in writing tutorials. In fact, of the 23 sub-skills, only three showed statistical difference at the .05 alpha level: organizing an essay, using grammar terms, and making correct word choices. The results of the 23 sub-skills are grouped by the categories of cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information and explained below.

Cultural Information

The results of cultural information showed almost no significant differences with the exception of the skill of organizing an essay (see Table 4). Although a post-hoc pairwise comparison failed to significantly distinguish the three groups at the adjusted alpha level, a descriptive analysis of means showed that L1 writers ranked organization slightly more important than L2 and Gen 1.5 writers. This is not to say that Gen 1.5 and L2 writers felt that organization was not important seeing as how the mean scores for all language groups on this item were above 4.5 on a scale where 4 represented important and 5 represented very important. In other words, all participants felt that organization was at least an important topic for tutors to address in a tutorial, but L1 writers felt it was slightly more important than did Gen 1.5 and L2 writers.

On one hand, this finding corroborates evidence from Eckstein (2018) which showed that L1 writers’ main reason for attending the writing center was to get help with organization. On the other hand, I had expected L2 writers to prioritize information about organization because of its relationship to intercultural rhetoric, a notion developed by Kaplan (1966) in which he claimed that cultural thought patterns influenced the way that individuals wrote. Individuals from different language backgrounds were thought to write in distinct, culturally reinforced ways (see Severino, 1993; Thonus 1993). This major tenet of intercultural rhetoric, that essay organization is culturally dependent, means that American academic culture tends to reinforce organizational patterns in essays that contravene what some L2 writers might expect from their native writing experiences. Accordingly, L2 writers might feel a stronger need than L1 or Gen 1.5 writers to receive instruction on how to organize their texts to be culturally appropriate. Given the findings for organization, it appears that this reasoning may be inaccurate. However, as one reviewer noted, it may not be that L2 writers were uninterested in organization, but that they had other, more pressing concerns. This indeed seemed to be the case at least according to research by Eckstein (2018) in which L2 writers much preferred help with grammar than with organization even though organization was highly rated in the present study.

Outside of organization, there were no other significant differences in the category of cultural information. The descriptive means reinforce this with no obvious pattern of difference among the three groups, though it is notable that the L1 group was least interested in information about correct idiom usage (M = 3.83) and L2 writers were least interested in choosing a topic/idea development (M = 3.90). These findings are unsurprising given that native English speakers have higher familiarity with idioms (Miner, 2018) and that L2 writers can improve their idea development through practice with writing more easily than grammar or other concerns (Storch, 2009). The fact that L1, L2, and Gen 1.5 writers generally had very similar perceptions about the relative importance of cultural information contradicted my expectations. Yet, the high mean scores suggests that cultural information was something all writers wanted irrespective of language background.

One interpretation of this finding is that writers equated cultural sub-skills with academic culture, not specifically American culture. Whereas students may have very different needs for American cultural information, they likely all need insights into academic culture and writing since no one is a native writer of academic prose. Hypothetically, more pronounced differences may have emerged had I asked writers to rank items about American culture (such as making writing sound culturally appropriate, or including American cultural references in essays) or had I asked participants to rank their reading needs (comprehending cultural references in writing prompts or reading passages). This reveals yet another limitation in the literature with the lack of precision in terms of what cultural information actually means. If cultural information relates to academic culture, then it appears that all writers, irrespective of linguistic background, feel that this should be addressed. However, if cultural information relates to intercultural rhetoric—specifically the notion that texts are organized in culturally distinct ways—or if it refers to cultural references, such as making writing sound “more American/British/etc.,” or comprehending culturally-based readings or writing prompts, then results may differ, and further research is needed to explore this. Such additional investigation could be invaluable in understanding precisely what kind of cultural information Gen 1.5 and L2 writers need.

Rhetorical Information

As with cultural information, writing center literature does not discuss what precisely tutors should address when discussing rhetorical information. As such, I interpreted it to include information that addressed the expectations of a particular audience or discourse community. For instance, I included an item about academic style/tone in this section because audience expectations influence a writer’s choices on this matter. An example of this might be a high register with many specialized vocabulary words for an audience of academic readers and a more familiar tone with some slang or abbreviations in an email to a friend. It is true that certain cultural expectations may similarly influence a writer’s style, which again shows a limitation of grouping writing sub-skills into discrete categories; nevertheless, I felt that the expectations of an audience within a discourse community would affect style and tone more than general cultural expectations.

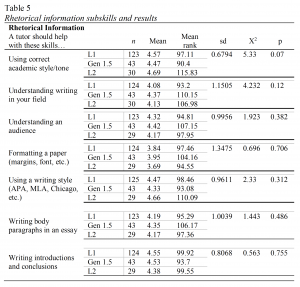

The results in Table 5 show that there was no statistically significant difference in participant responses among all seven rhetorical information sub-skills. The first item, about academic style/tone, approached significance, with a p-value of .07. The lack of significant difference within rhetorical information may be explained in at least two ways. It may be that the items were worded in such a way that they did not distinguish L1 needs from those of Gen 1.5 or L2 writers. For example, the rhetorical information described in the survey may have been too general while the rhetorical information that L2 writers particularly need may be much narrower, such as help knowing how to write persuasive appeals in English. Another possible explanation, however, is that L1 writers felt just as much of a need for rhetorical information as multilingual writers. In other words, L1 writers may have felt that their “lifetime of exposure to the . . . rhetorical structures . . . of writing in English” (Reid & Powers, 1993, p. 26) failed to provide them sufficient insights to warrant skipping rhetorical instruction in a writing center tutorial. Alternatively, it may be that writers, irrespective of language background, had been conditioned to think rhetorically thanks to an emphasis on audience needs/expectations in academic writing and composition pedagogy. Repeat attendees of the writing center might especially have been socialized into actively considering the rhetorical impact of their writing and thus seek that help.

Despite the lack of significant differences, the descriptive mean scores still reveal some insights into writers’ preferences for rhetorical information. In fact, while both L1 and Gen 1.5 writers ranked many rhetorical sub-skills higher than L1 writers, in reality it was Gen 1.5 writers who generally ranked rhetorical sub-skills highest in importance. This may reflect the “ear-learner” status of Gen 1.5 writers described by Reid (1998). Because of their aural acquisition of English, these students may feel the least prepared to engage in American academic writing and rhetoric (Peña, 2014; Thonus, 2003).

Since these differences are only based on descriptive data, not inferential results, further investigation is needed to validate these observations. Moreover, additional research is needed to understand the kind of rhetorical information multilingual writers may need, particularly if it is narrow, assignment-specific help. In the meantime, however, it is possible to state as a generality that writers across all language groups in this study indicated that rhetorical information was important for tutors to address in writing center tutorials.

Linguistic Information

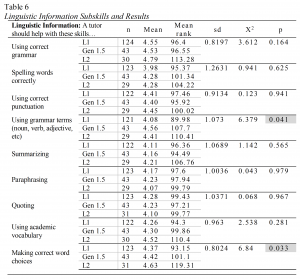

The last section investigated linguistic information, and it is this section that naturally seems most likely to reflect salient differences between the preferences of L1, L2, and Gen 1.5 writers. This is because L1 writers are exposed to English from birth and therefore, truly have a lifetime of experience and exposure to the English language whereas L2 writers do not and Gen 1.5 writers may be in between. As such, it stands to reason that L2 writers would be more likely to rate language information as highly important for tutors to address.

To measure linguistic information, I grouped together nine items about grammar, punctuation, spelling, word choice, vocabulary, and phrasing (summarizing, paraphrasing, quoting). Again, many of these items might have fit just as well in other information categories, particularly the phrasing items, so some care must be taken in interpreting the results in Table 6. In total, only two sub-skills resulted in statistically significant results: using grammar terms and making correct word choices. Neither of these sub-skills were related directly to grammar instruction.

The first significant finding emerged when asked if tutors should use grammar terms during tutorials. The descriptive means showed that the multilingual writers ranked this sub-skill as more important than L1 writers, though the pairwise post-hoc comparison did not bear this out statistically. It might make sense that both Gen 1.5 and L2 writers would value grammar terms because they take grammar classes where terms such as noun, verb, adjective, and so on are used. Thus they are more likely to benefit from the kind of meta-linguistic shorthand they provide (Thonus, 2003). L1 writers, on the other hand, are generally thought to have an intuitive knowledge of English grammar and may be less familiar with grammar terms.

The other significant finding showed that L2 writers felt it was very important for tutors to help them make correct word choices. Again, the mean scores showed that all writers felt this was important, but L2 writers differed significantly from L1 writers in a post-hoc analysis (p = .009). This suggests that L2 writers wanted word choice help and vocabulary information from their writing center specialists while L1 writers felt it was slightly (but significantly) less important.

These two findings are interesting because they show L2 writers placing a higher value on language information than L1 writers, a finding that is reinforced by numerous writing center reports (e.g., Harris & Silva, 1993; Powers, 1993; Williams, 2004). However, the more surprising finding perhaps is that seven other sub-skills showed no significant differences among participant responses. Whereas writing experts assume that L2 writers need and want linguistic information more than L1 writers who have an intuitive knowledge of the English language (see Harris & Silva, 1993; Raimes, 1985; Thonus, 2003), the results from this study suggest that even L1 writers crave linguistic support. This may be because language issues such as grammar, punctuation, and spelling are easier to change than bigger issues such as content or organization, so when given a choice, L1 writers may prefer to focus on easier surface-level concerns. While this explanation seems logical, it should nonetheless be emphasized that L1 writers in this study and elsewhere (Eckstein, 2018) also wanted help with organization, more so than L2 writers, suggesting that a view of L1 writers in which they are thought to bypass difficult revisions in favor of small edits is probably too simplistic. Instead, even L1 writers may legitimately want and need linguistic information to fill in gaps of schematic grammar knowledge.

This does not necessarily mean that L1 writers need the same linguistic information as L2 writers, (Eckstein, 2018; Eckstein & Ferris, 2018). L2 writers may need more support for syntactic issues related to verb structure while L1 writers might need help with sentence boundaries, both of which can be considered grammar issues. The survey items in this study did not provide the level of nuance needed to see these differences, and even if they had, it is unclear whether students possess sufficient grammatical knowledge or self-awareness of their writing to accurately diagnose their needs. Thus, further research is warranted to discover the types of grammar help writers of different language backgrounds both prefer and need

Conclusion

Overall, the results from this study demonstrate that L1, L2, and Gen 1.5 writers are more alike than different in terms of their self-reported preferences for cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information. In reality, the results show only three sub-skills out of twenty-three with statistically significant variation: organizing an essay, using grammar terms, and making correct word choices. L2 and Gen 1.5 writers only ascribed slightly more importance to the sub-skills of using grammar terms and making correct word choices, reflecting a heightened emphasis on grammar, and L1 writers tended to be more concerned with organization than their multilingual peers.

The otherwise overwhelming similarities among the three language groups seems to contradict both intuitive assumptions about L2 writers’ needs as well as recommended best practices for working with these writers (see Powers, 1993; Reid & Powers, 1993). The assumptions of such recommendations being that L2 writers who lack intuitive cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information would need tutors who could function in an informant role, not merely as a reflective listener or Socratic coach. The results indicate that there is no obvious pattern of difference in what cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information writers value in a tutorial and suggest that perhaps all writers, irrespective of language background, appreciate and need tutors who function as informants. This may be especially true within academic writing contexts where writers genuinely lack sufficient schemata or are unsure about their schematic knowledge of academic prose. Whereas L1 writers may feel very comfortable with their cultural schemata in general, they may not feel as comfortable with academic schemata, which may have caused them to respond to the survey in ways that were very similar to Gen 1.5 and L2 writers. For instance, all writers reported feeling that tutors should help with understanding American academic writing, using appropriate academic style/tone, avoiding plagiarism, formatting a paper, doing research, summarizing, paraphrasing, quoting, using academic vocabulary, and using a writing style (such as APA or MLA), all of which are components of academic writing and culture.

There are a number of limitations to these research findings given the way data was collected. Although responses came from a national survey, respondents self-selected to participate, which may have biased the population toward a preference for tutor-informant roles, and thus the findings might be most relevant for repeat and frequent writing center visitors who are perhaps similarly pre-disposed to obtain tutor information. Moreover, the survey was necessarily based on an idiosyncratic and general classification of tutorial information. This is because, despite the notion of informant roles existing in L2 writing center recommendations for a quarter-century, no codified or even proposed inventory exists to describe cultural, rhetorical, or linguistic information that writers might need. This study developed a prototype for such an inventory, but there is clearly room for additional refinement and validation. Finally, writers in this study reported preferences, not necessarily needs, which could vary dramatically among populations, as could writers’ understanding of composition and rhetorical terms such as “grammar” and “organization.”

While I did not distinguish between wants and needs in this research, future investigations could do so by examining writers’ written work for obvious limitations in their awareness of cultural, rhetorical, or linguistic information and comparing those results to students’ desires for feedback or even the actual content of their consultations. Such an investigation would most likely find more differences in what writers from different language groups need and receive. Furthermore, this study was limited by the lack of consensus of what informant categories fully entail. Inasmuch as writing specialists tend to agree that L2 writers need tutor informants, but that this study failed to distinguish students’ preferences across language groups, it may be that the instrument used in this study was not sufficiently attuned to writers’ preferences. Thus, additional research at the discourse level—perhaps through interview-based inquiry for writers and tutors—is needed to determine more precise descriptions of tutor-based information. After a better, more specific inventory is developed, a replication of the present study could either validate more salient differences across writers’ linguistic backgrounds or triangulate the current findings.

Despite the limitations of this research, the results nevertheless show that writers across language groups, not just L2 writers, valued cultural, rhetorical, and linguistic information in writing tutorials. In cases where writers legitimately need this information to improve as writers and to improve their writing, tutors should be willing to offer it regardless of the writer’s linguistic background. Whether this is provided through direct instruction or through non-direct, minimalistic, or Socratic means may still require further insight. For now, however, Powers’ (1993) advice for tutors to perform an informant function for L2 writers seems to be at once both helpful and insufficient. It is helpful inasmuch as writers do indeed want tutor-informants to help them in the writing center; it is insufficient because L2 students are not alone in craving this kind of tutoring. It appears in this instance that L2 students want and possibly need the same information as L1 and Gen 1.5 writers as well.

References

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center: Towards an evidence-based practice. New York, NY: Peter Lange.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Bell, J. H. (2000). When hard questions are asked: Evaluating writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 21(1), 7–28.

Blau, S., Hall, J., Davis, J., & Gravitz, L. (2001). Tutoring ESL students: A different kind of session. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 25(10), 1–4.

Blau, S., Hall, J., & Sparks, S. (2002). Guilt-free tutoring: Rethinking how we tutor non-native-English-speaking students. Writing Center Journal, 23(1), 23–44.

Blau, S. R., Hall, J., & Strauss, T. (1998). Exploring the tutor/client conversation: A linguistic analysis. Writing Center Journal, 19(1), 19–48.

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (Eds.). (1989). Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Bransford , J., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Memory, 11(6), 717–26.

Brooks, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 15(6), 1–4.

Brown, R. (2010). Representing audiences in writing center consultation : A discourse analysis. Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 72–99.

Carrell, P. L. (1983). Background knowledge in second language comprehension. Language Learning and Communication, 2(1), 25-34.

Carrell, P. L., & Eisterhold, J. C. (1983). Schema theory and ESL reading pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 17(4), 553–573.

Clark, I. R. (1985). Writing in the center: Teaching in a writing center setting. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Clark, I. (2001). Perspectives on the directive/non-directive continuum in the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 22(1), 33-58.

Cohen, A. D., & Olshtain, E. (1993). The production of speech acts by EFL learners. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 33-56.

David, N. (2009). Perceptions from the writing center: Community college writing center tutor and director perceptions of ESL writing errors (Unpublished master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Eckstein, G. (2016). Grammar correction in the writing centre: Expectations and experiences of monolingual and multilingual writers. Canadian Modern Language Review, 77(3), 360–382. http://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.3605

Eckstein, G. (2018). Goals for a writing center tutorial: Differences among native, non-native, and generation 1.5 writers. Writing Lab Newsletter, 42(7–8), 17–23.

Eckstein, G., & Ferris, D. R. (2018). Comparing L1 and L2 texts and writers in first-year composition. TESOL Quarterly, 52(1), 137–162. http://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.376

Ferris, D. R. (2009). Teaching college writing to diverse student populations. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Ferris, D. R., & Hedgcock, J. S. (2014). Teaching L2 composition: Purpose, process, and practice (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Harris, M., & Silva, T. (1993). Tutoring ESL students: Issues and options. College Composition and Communication, 44(4), 525–537.

Jaeger, G. (2016). (Re)Examing the Socratic Method: A lesson in tutoring. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 14–20.

Kaplan, R. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. Language Learning, 16(1-2), 1-20.

Mandler, J. (1984). Stories, scripts, and scenes: Aspects of schema theory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Miner, S. (2018). Reading idioms: A comparative eye-tracking study of native English speakers and native Korean speakers (Unpublished master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433–446.

Peña, J. (2014). Improving a generation 1.5 student’s writing. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 18(3). Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol11num2/bloch

Powers, J. K. (1993). Rethinking writing center conferencing strategies for the ESL writer. Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 39-47.

Raimes, A. (1985). What unskilled ESL students do as they write: A classroom study of composing. TESOL Quarterly, 19(2), 229–258.

Reid, J., & Powers, J. (1993). Extending the benefits of small-group collaboration to the ESL writer. TESOL Journal, 2(4), 25–32.

Reid, J. (1998). “Eye” learners and “ear” learners: Identifying the language needs of international student and U.S. resident writers. In P. Byrd & J. M. Reid, Grammar in the composition classroom: Essays on teaching ESL for college- bound students (pp. 3-17). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Roberge, M., Siegal, M., & Harklau, L. (Eds.). (2009). Generation 1.5 in college composition: Teaching academic writing to U.S.-educated learners of ESL. New York, NY: Routledge.

Rumelhart, D. E. (1980). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition. In R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, & W. E. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension (pp. 33-58). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696-735.

Scollon, R., Scollon, S. W., & Jones, R. H. (2011). Intercultural communication: A discourse approach (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Severino, C. (1993). The ‘doodles’ in context: Qualifying claims about contrastive rhetoric. The Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 44–61.

Shamoon, L. K., & Burns, D. H. (2008). A critique of pure tutoring. In R. W. Barnett & J. S. Blumner (Eds.), The Longman guide to writing center theory and practice (pp. 225-241). New York, NY: Pearson Longman.

Staben, J., & Nordhaus, K. (2009). Looking at the whole text. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors (2nd ed., pp. 78–90). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Steffensen, M. S., Joag-dev, C., & Anderson, R. C. (1979). A cross-cultural perspective on reading comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 15(1), 10–29.

Storch, N. (2009). The impact of studying in a second language (L2) medium university on the development of L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(2), 103–118. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2009.02.003

Thompson, J. C. (1999). Beyond fixing today’s paper: Promoting metacognition and writing development in the tutorial through self-questioning. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 23(6), 1-6.

Thompson, I., Whyte, A., Shannon, D., Muse, A., Miller, K., Chappell, M., & Whigham, A. (2009). Examining our lore: A survey of students’ and tutors’ satisfaction with writing center conferences. Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 78–106.

Thonus, T. (1993). Tutors as teachers: Assisting ESL/EFL students in the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 13(2), 13-26.

Thonus, T. (1998). What makes a writing tutorial successful: An analysis of linguistic variables and social context (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

Thonus, T. (2003). Serving generation 1.5 learners in the university writing center. TESOL Journal, 12(1), 17–24.

Tseng, T. J. (2009). Theoretical perspectives on learning a second language. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), ESL writers: A guide for writing center tutors (2nd ed., pp. 18-32). Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Wagoner, B. (2013). Bartlett’s concept of schema in reconstruction. Theory & Psychology, 23(5), 553-575.

Weigle, S. C., & Nelson, G. L. (2004). Novice tutors and their ESL tutees: Three case studies of tutor roles and perceptions of tutorial success. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(3), 203–225.

Williams, J. (2004). Tutoring and revision: Second language writers in the writing center. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(3), 173–201. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2004.04.009

Appendix A: Tutor Informant Roles Survey

Writing center tutors are not always able to address all aspects of writing in a single visit. So of the topics and skills listed below, which do you think are the most important for tutors to help with? Use the following scale:

Notes

- The term Gen 1.5 is used in this article to encompass a broad and heterogeneous group composed of what Roberge, Siegal, and Harklau (2009) term Generation 1.5 learners and what Ferris (2009) referred to as early- and late-arriving residents. These are writers who lived some or all of their life in America prior to college, spoke a non-English language in their home growing up, received formal education in their L2 (English), and received some educational training that was influenced at least partially by their English language learner status (see Ferris & Hedgcock, 2014). Reid (1998) further described these students as “ear learners” because of their propensity to learn English (along with cultural information) through aural means such as American television, school conversations, and so on rather than grammar-based book study as many L2 writers, or “eye learners” do. ↑