Wenqi Cui

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Abstract

This study explores the identity construction of an individual multilingual writing center tutor in tutoring sessions at an American university. Discourse analysis approach is applied to analyze this multilingual tutor’s language use when interacting with his tutees. The findings indicate that the participant tutor takes on multiple identities: a writing center tutor, a negotiator and collaborator, and a language ambassador. These identities are contingent, fluid, and multifaceted depending on the interactions between the tutor and his tutees. Furthermore, this participant tutor’s identities are co-constructed in the interactions with his tutees through the incorporation of his multilingual resources, and through language and linguistic features which are assigned social meanings by writing center communities.

Keywords: multilingual tutor, identity construction, writing center, language indexicality

Introduction

There have been a large number of studies on writing centers in the past decades, involving almost every aspect of writing center communities, from tutoring strategies, tutor training, relations between tutors and tutees, writing center and curriculum, identity of tutors and tutees, and so forth. Recently, the interest of multilingualism in writing centers has been burgeoning. Many writing center directors have embraced other languages and cultures in their writing center communities (Babcock & Thonus 2012; Condon 2012; Denny 2010; Greenfield & Rowan, 2011; Hutchinson & Gillespie, 2016; Rafoth, 2015). Most scholarship on the multilingual context of writing centers is chiefly on effective tutoring strategies for “English as a Second Language (ESL)” tutees (Blau, Hall & Sparks, 2002; Bruce & Rafoth, 2004; Harris, 1997; Leki, 1992; Severino, 2004; Silva, 1997; Williams, 2002), while research on multilingual tutors’ roles/identities is scarce. In previous studies on multilingual tutees, most of their tutors have been either identified as monolingual native English speakers or their linguistic status has been overlooked if they are multilinguals (Babcock, 2016; Zhao, 2017). Regardless of their shared cultural knowledge and writing experiences with multilingual tutees, multilingual tutors’ roles/identities are overlooked in prior literature. This study aims to address some of these neglected areas of research and to respond to the call for diversity in writing centers, embracing multilingual tutees, as well as tutors, via delving into how an individual multilingual writing center tutor co-constructed and negotiated his identities in tutorial interactions.

In what follows, I begin by reviewing the literature on identity of L1 (English as a first language) writing center tutors. Then, I explicate the three theories applied in this study: identity co-construction, language and indexicality, and tutoring culture in writing center communities. Afterward, I report my findings from the collected observation data, indicating the identity construction of a multilingual writing center tutor. Finally, this paper concludes with a couple of recommendations for further research.

Literature Review

Studies on the Identity of L1 Writing Center Tutors

Previous literature, primarily on L1 (English as a first language) writing center tutors’ identity, described them as cultural informants (Myers, 2003), rhetorical informants, cultural and linguistic informants (Harris & Silva, 1993), cultural ambassadors (Fox, 2003), collaborators with tutees, mediators between student writers and their instructors, and helpers of L2 (English as a second language) student writers (Bruce & Rafoth, 2016), according to the roles they played in tutorial sessions. Since “tutoring involves multiple responsibilities” (Rafoth, 2016, p. 5), these tutors are likely to play multiple roles. Sharon Myers (2003) points out that “being a culture informant includes being a language informant” (p. 56). Likewise, Muriel Harris & Tony Silva (1993) describe tutors’ roles as “tellers of cultural, rhetorical, and/or linguistic information” when working with ESL learners (p. 533). The multiple roles that L1 tutors played indicate that, when tutoring a piece of writing, L1 tutors not only help tutees with their grammar, vocabulary, and diction, but also provide with cultural information related to American society and rhetorical knowledge uniquely applied in western writing style.

Since the 1990s, a growing number of studies have begun to focus on multilingual student writers, specifically on tutorial strategies for these writers. Meanwhile, many writing centers were inclined to espouse diverse and pluralistic milieu by hiring multilingual tutors or encouraging bilingual tutors to apply code-switching or code-mixing during tutoring sessions with multilingual writers (Bruce & Rafoth, 2016). However, research on multilingual tutors, in particular on their identities, is scarce. Several studies on writing center tutors show that it is not easy for multilingual tutors to establish their legitimate membership in writing center communities because Native English-Speaking tutors are preferred over Nonnative English-Speaking tutors (Chang, 2011; Zhao, 2017) and because they are “rarely expect[ed] in the writing center” (Wablstrom, 2013, p. 10). Nevertheless, it remains unclear regarding the roles multilingual tutors play in the writing center, the challenges that multilingual tutors encounter in terms of their membership, and their contributions to the diversified writing center community. To establish a linguistically and culturally diverse and inclusive community, it is especially important to investigate how multilingual tutors, who are historically marginalized, earn or fail to earn their legitimate membership in historically monolingual writing center communities. This investigation is exigent, especially in the current writing center landscape, as it becomes increasingly more linguistically and culturally diverse. Accordingly, this study attempts to explore a multilingual writing center tutor’s identity construction in a writing center through analyzing his language and his language’s indexed social meanings when tutoring student writers.

Identity Theory

Norton (1997) defines identity as people’s understanding of their relationship to the world and how the relationship is constructed across time and space. On the one hand, individuals possess numerous social identities in response to certain communities, and each type of identity is socially and culturally shaped through meeting particular expectations when interacting with other individuals in a community. In other words, identities are co-constructed because of social interactions. Sally Jacoby and Elinor Ochs (1995) define co-construction as the “joint construction of a form, interpretation, stance, action, activity, identity, institution, skill, ideology, emotion or other culturally meaningful reality” (p. 171).

Individuals’ identities are shaped by historical, cultural, and social contexts and communities where they live and grow up (Bucholtz & Hall, 2004; Cox, Jordan, Ortmeier-Hooper, & Schwartz, 2010; Eckert & McConnell-Ginet, 1995; Goffman, 1959; Jacoby & Ochs, 1995; Kramsch, 2000; Mendoza-Denton, 2008; Norton & McKinney, 2011; Pavlenko & Lantolf, 2000; Schiffrin, 2006; Vickers & Deckert, 2013). These communities vary in terms of their linguistic, discursive, and cultural repertoires as well as their embedded values, ideologies, and tenets. In “communities of practice” (Goodwin, 1990; Wenger, 1998), an individual socializes with other community members through language to acquire linguistic and cultural competence, the knowledge of sociopolitical ideologies, and to live up to established local expectations of the specific community. Through socializing in social practices and activities, individuals understand the expectations of a community, and then modify or “construct and evolve his/her identity” (Bhowmik, 2016; Godley & Loretto, 2013) to fit into the expectations of the community. In this way, an individual establishes his/her membership in a community. These social contexts are not static, rather, they are evolving across time and space. In addition, people establish relationships and perform a variety of different social roles (Goffman, 1981) when in or moving between various “communities of practice” (Goodwin,1990; Wenger, 1998). Therefore, identities are flexible, fluid, and multi-faceted (Bailey, 2001; Bucholtz & Hall, 2004; Jacoby & Ochs, 1995; Kramsch, 2000; Mendoza-Denton, 2008; Norton & McKinney, 2011; Pavlenko & Lantolf, 2000; Schiffrin, 1996; Schiffrin, 2006).

On the other hand, human agency plays an important role in individuals’ identity (re)construction. Individuals define and position themselves in various communities where they sense themselves by identifying differences from other people as well as finding commonalities with others. Human beings are active agents in selecting specific ways to perform their roles and in “position[ing] themselves in relation to those others” (Schiffrin, 1996, p. 197) in various communities, thus constructing, negotiating, reproducing, resisting, or transforming their identities. For example, when participating in a new community, people tend to reconstruct their identities through conforming to, negotiating, or resisting the practices and performances expected from the new community. What complicates this issue is that these individuals’ former identities do not vanish, instead, they co-exist or are intertwined with their newly developed identities. Regarding identity construction, communities decide what expectations individuals should meet, whereas human agency determines whether and how they establish their membership in these communities.

Language and Indexicality

Socializing with expert members allows newcomers to establish their membership and construct their identities in a community. In the process of socialization, language functions not only as a medium of communication but also as a social practice through which social relationships of community members are defined, negotiated, reinforced, or resisted (Norton & McKinney, 2011). Put differently, language is central to identity construction: it is the marker of social identity as well as an instrument to maintain social identity in communities (Bailey, 2001; Bucholtz & Hall, 2004; Hansen & Liu, 1997; Jacoby & Ochs, 1995; Lippi-Green, 1997; McNamara, 1997; Mehan, 1996; Norton, 1997; Ochs, 1992; Schiffrin, 2006; Vickers & Deckert, 2013). Communities vary in respect of their sociocultural contexts such as social identities and social activities which are constituted by social stances and acts. Language and linguistic features reflect and index multiple dimensions of the sociocultural context (Ochs, 1992, p. 335). In a community, competent members have been socialized through language to obtain information as well as to learn to communicate and interpret these social stances and acts indexed by linguistic structures.

Individuals establish, mediate, maintain, and reinforce the specific aspects of their identities and their relationships with other members by choosing to use particular language and language forms when socializing and interacting. By doing this, social roles and social orders are established and inherited. Furthermore, neither society nor language is static. Language evolves with the development of social and cultural environments. Consequently, new words and definitions are constantly created while outdated terms are abandoned. This ongoing phenomenon indicates that social meanings, stances, and social acts are continuously developing. Therefore, analyzing language use and its social meanings can help researchers understand what and how individuals’ social identities are culturally and historically constructed in a community. In particular, as Ben Rafoth (2010) contended “conversation is the key idea behind writing centers” (p. 146). Language socialization in conversations at writing centers not only prompts “better writing” (Rafoth, 2010, p. 150), but also constructs identities of tutors as well as mirrors the evolvement of writing center communities in terms of their culture and history.

Writing Center Community

Like other “communities of practice” (Goodwin, 1990; Wenger, 1998), writing center communities have their specific social activities, acts, and stances. An essential part of the writing center community is tutoring, during which tutors’ roles “are bound by set of reciprocal expectations and obligations” (Schiffrin, 1996, p. 196) and their identities are “co-constructed, performed, and displayed through language [in tutorials] but mediated by the particular uses of language with [social] meanings” aligned with writing center communities. (Vickers & Deckert, 2013, p, 118). That is to say, “tutor identities are reflective of their particular [writing] centers’ tutoring cultures” (Friedrich, 2014, p. 56). To establish their legitimate membership, writing center tutors, multilingual tutors and otherwise, are supposed to meet the ongoing and evolving expectations and cultures of writing center communities.

Tutoring cultures and practices in writing center communities are historically and culturally situated as well as constantly evolving across time and space. Writing centers have been created, developed, and transformed in the past decades from “remedial lab”, “clinics”, to “centers” (Chang, 2011); accordingly, tutoring cultures and roles have evolved from “fixing errors/problems in tutees’ writing to “produc[ing] better writers” (North, 1995, p. 438). Rather than only focusing on grammatical issues or clarity of a piece of writing, tutors assist tutees to acquire and review rhetorical situation knowledge, genre knowledge, and writing process knowledge, as well as help them learn to transfer this knowledge to different writing tasks and contexts. Correspondingly, the contemporary tutoring sessions emphasize improving tutees’ writing expertise rather than a specific piece of writing, which can be seen from the language that tutors use.

In addition to the tutoring focus, tutee-centered and negotiation-oriented approaches are encouraged in tutoring sessions, as Harris and Silva (1993) pointed out that “writing center pedagogy has given high priority to working collaboratively and interactively, a major goal of a tutor is to help students find their own solutions” (p. 532-533). This approach is aligned with the value and tenet of writing center communities to cultivate good writers.

The above acts and activities reflect the stances and expectations from writing center communities. Putting it differently, a legitimate tutor is expected to focus on cultivating a good writer and applying collaborative and interactive tactics in writing center tutoring practices. Meanwhile, these constantly developing stances and indexical acts are mirrored in the language and linguistic features in tutorials which shape the identity of writing center community members.

In brief, the identity constructions of multilingual writing center tutors are shaped by the historically established and continuously evolving writing center conventions as well as by their human agency. However, it is more complicated for multilingual tutors to establish their identity and legitimate membership in historically monolingual writing center communities. In this case, understanding multilingual tutors’ identity construction is a precondition of building an inclusive community that embraces multiple cultures, languages, and language varieties. For this reason, this research explores the dynamic and complexity of identity construction through analyzing a multilingual tutor’s language use and its indexed social meanings in tutorial sessions. This exploration was guided by the following research questions:

- What identities do multilingual tutors construct during tutorial sessions?

- How do their identities impact multilingual tutors’ tutoring praxis?

Method

This study was conducted at the writing center of a medium-sized university in Western Pennsylvania (IRB Log#: 17-252). In this writing center, the majority of tutors were L1, who used English as a first language. However, there were nine multilingual tutors who used English as a second language. Like L1 tutors, these multilingual tutors attend a series of training sessions each semester regarding tutoring strategies and theories. Considering these tutors’ availability, one multilingual tutor was recruited for this study using a convenient sample. This participant tutor was observed once a week for five weeks in a row. These five tutoring sessions were audio-taped. The collected data included observation notes and audio-taped observations. In the observed five tutorial sessions, the participant multilingual tutor worked with five different L1 tutees. This study does not intend to generalize the findings to other tutors or writing centers given the fact that each writing center has its own conventions and each tutor has his/her own tutoring style and plural cultural and linguistic resources. Rather, this case study on one multilingual tutor focuses on the nuances of his tutoring sessions and to offer rich descriptions of his language use and identity construction.

Participant

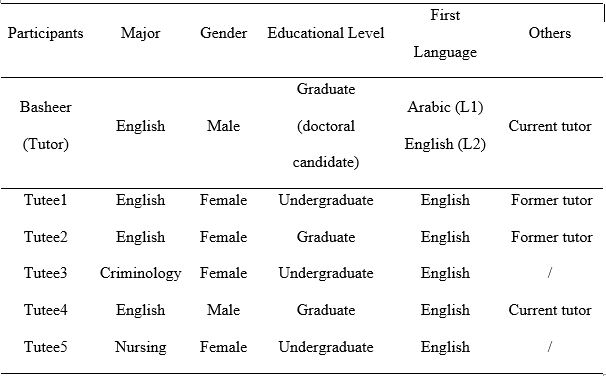

The tutor participant in this study was a multilingual tutor, Basheer (pseudonym), from a Middle Eastern country and had been working as a voluntary writing center tutor for five weeks. Basheer speaks Arabic (L1). English is his second language (L2). He earned his master’s degree in America and is currently a doctoral candidate at the English department. When this study was conducted, Basheer had been tutoring twice each week at the Writing Center. For this semester, he did not get paid because his visa only allowed him to work limited hours. In the following semesters, Basheer continued to work at the Writing Center but as a paid tutor. Though in this study five tutees were involved, I only focused on Basheer and his language features during those tutorial sessions. The information of the five tutees is included here (See Table 1) because Basheer’s identities were primarily co-constructed through his interactions with these tutees. Including the information of the five tutees will help readers envision the interactions between Basheer and the tutees. Among the five L1 tutees, four were females and one was a male, three of them majoring in English, the other two majoring in Criminology and Nursing. Two of the tutees were graduate students and three were undergraduates. Three of the five tutees used to be tutors at this writing center. Therefore, the social meaning indexed by the language used in the interactions was expected to be shared by the three tutees and Basheer because all of them belonged to the writing center community.

Table 1: Demographic Information of the Participants (one tutor and five tutees)

Data Collection and Analysis

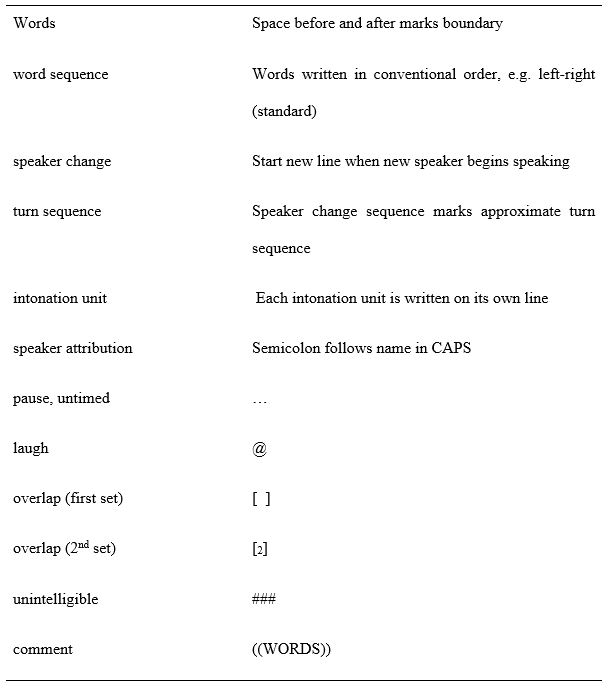

The collected dataset includes five audio-taped tutorials between Basheer and different tutees, as well as the researcher’s observation notes. These observation notes provided with the context of each tutoring session and some non-linguistic information such as the tutor’s gestures that audio-recorder did not capture, which helped the researcher better understand the interactions between the tutor and tutees. The accumulative five-hour long audio recordings encompassing of Basheer’s five tutorials were transcribed by the researcher, and subsequently, member checked with the participant tutor, Basheer. The audio-taped observations were transcribed following the guideline of transcription conventions (See Appendix A) by John W. Du Bois, Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, Susanna Cumming, & Danae Paolino (1993).

This study utilized discourse analysis approach to analyze the transcribed tutorials. According to Stephanie Taylor (2003), there are primarily four approaches to discourse analysis: the first approach focused on language itself; the second is interested in the use of language and interaction between interlocutors; the third approach looks for patterns in the language associated with a particular topic or activity; and the fourth approach focuses on the patterns of language in a society or culture. I attempted to investigate a multilingual writing center tutor’s patterns of language use and related social meanings as well as how these aspects co-constructed this tutor’s identity. Therefore, the fourth approach to discourse analysis fits my research purpose and enables me to track the particular stances and acts displayed by the tutor’s discursive features that index social meanings assigned by writing center communities.

I began the process of analysis by reading the transcribed tutorial sessions repeatedly, taking notes and focusing on the patterns of language use and linguistic features with social meanings associated with writing center communities. Then I stepped back and thought about how in each talk, Basheer used the language to negotiate and construct a sense of himself in relation to the writing center community, to establish his legitimacy in this community, and to reframe the relationship with his tutees. The writing center community values writing concepts and practices that facilitate writers’ writing development as well as collaboration between tutors and tutees. Accordingly, I extracted excerpts indexing the social meanings and stances assigned and expected by the writing center community, with which Basheer positioned himself as a competent writing center tutor, negotiator, and collaborator. Additionally, he established and negotiated the particular aspects of his identity as a multilingual persona by incorporating his linguistic and cultural resources in his tutoring sessions, hence identifying himself as a cultural ambassador.

Social identities and social orders are recognized and established based on the social practices mediated by discourses in communities. In this case, discourses include the interactions during tutorial sessions between tutors and tutees. Discourse analysis allows me to examine the complex identity construction across the five tutoring sessions, pinpointing various aspects of the tutor’s identity and capturing the shifts between his identities during his interactions with different tutees. In this study, by using discourse with social meanings assigned by writing center communities and ideas derived from his multilingual experiences, the participant tutor, Basheer, constructed his identity as a tutor with his multilingual skills to gain his legitimate membership in the writing center community.

Findings

Tutors’ identities are contingent and multifarious, depending on both tutors’ decisions and “choices” of language and tutoring strategies, as well as on “tutees’ expectations” when interactions process (Cox, 2016, p. 63). In the five tutoring sessions, the tutees brought their manuscripts ranging from applications for graduate schools, scholarship materials, to course writing. Each tutee came with individualized focuses and expectations. Therefore, Basheer had to vary his tutoring practices to satisfy tutees’ different requirements as well as follow the tutoring culture in this writing center. At the beginning of each tutoring session, Basheer started with inquiring the tutees’ demands and expectations for the tutorials, such as “what are we doing today?” To satisfy tutees’ varying requirements, either on rhetorical or linguistic issues, Basheer had to perform different roles, such as a rhetor or a language professional. Accordingly, Basheer established different identities and shifted between these pluralistic identities, being contingent on who he interacted with and for what purpose.

The discourses in the following excerpts display what and how Basheer performed multifaceted and intertwined roles which indexed his identity as a writing center tutor as well as his identity as a multilingual language user.

Identity as a Writing Center Tutor

The following excerpts (Excerpt 1A, Excerpt 1B, and Excerpt 1C) indicate how Basheer constructed his identity as a writing center tutor through discourses that indexed the expected and anticipated practices in the writing center. For example, across the five tutoring sessions, Basheer emphasized the importance of rhetorical knowledge in writing, such as the potential readers, the requirements of the professor, and genres for specific writing purposes.

In excerpt 1A, Basheer and Tutee 1 were working on her personal statement for applying to a graduate school. Basheer helped Tutee1 to format her manuscript and raise her audience awareness. As a tutor, Basheer constructed his identity as a tutor by emphasizing the importance of being aware of audiences.

Excerpt 1A (Tutorial 1, Tutee 1)

135 BASHEER: I feel like you have to have some headings subheadings

136 [I feel] ((emphasis tone))

137 TUTEE 1: [do you feel so]

138 BASHEER: I feel so ((emphasis))

139 TUTEE 1: okay

140 BASHEER: I think it’s gonna be very open it doesn’t have to be en…

141 you know it’s really it’s really it’s something

142 that school may require they want the whole like

143 no headings nothing they just want the whole

144 you know the thing [but] I feel

145 TUTEE 1: [um]

146 BASHEER: as a reader I feel I need to know what you are talking about in the section

147 TUTEE 1: Ah…okay

148 BASHEER: so…if you could have a look at other examples of …

149 they didn’t provide a certain format they just said do this

150 TUTEE 1: uh huh uh huh

151 BASHEER: so I would I would … actually…

152 put some headings if you talk about

153 your history teaching experiences something like that

154 TUTEE 1: okay uh okay

In this excerpt, Basheer suggested that Tutee 1 should add subheadings in her writing through emphasizing audience/reader consciousness and genre awareness. By saying “as a reader I feel I need to know what you are talking about in the section” (line 146); “if you could have a look at other examples of …” (line 148) and “they didn’t provide a certain format they just said do this” (line 149), Basheer implied that a writer should consider his/her readers and the required genre in writing. What he did in this situation is consistent with a writing center tutor’s job: to “produce better writers” (North, 1995, p. 438), which emphasizes the importance of writing concepts such as rhetorical situation, audience awareness, and genre conventions. In other words, Basheer’s discourse pertaining to audience awareness and rhetorical situation aimed to develop the tutee’s writing expertise.

Identity is constructed by not only what an individual does or says but also by what he/she chooses not to do or say. In Excerpt 1B, Basheer and Tutee 1 worked on her personal statement for a graduate school, during which they talked about whether they should focus on editing issues.

Excerpt 1B (Tutorial 1, Tutee 1)

203 BASHEER: we might want to make it shorter let’s go to the other part

204 TUTEE 1: it’s [sort of awkward] there yeah

205 BASHEER: [this this part] yeah that’s fine

206 TUTEE 1: I’m trying to say [2that’s a fact now]

207 BASHEER: [2you could] you could say that’s that background included

208 so that we could follow

209 TUTEE 1: okay

210 BASHEER: you mean by that now we are doing editing

211 like @ [I think that’s good to…] ((sounds sorry, trying to explain))

212 TUTEE 1: [that’s okay I need that as well] I apply to an English program

213 it has to be as good as it can be

When Basheer and Tutee 1 began to reword a sentence, Basheer sounded sorry and explained that “we are doing editing like I think that’s good to…” (line 210-211). Actually, Basheer was interrupted by Tutee 1 who used to be a writing center tutor. Tutee 1 understood what Basheer was attempting to say about the implication of editing for a writing center community. Tutee 1 shared with Basheer the “tutoring culture” that aims to cultivate a good writer, thus understanding why Basheer was hesitant. Basheer and Tutee 1 both were aware that editing should not be the primary concern at the early stages of writing. Emphasis on errors in usage, diction, or grammar in early drafts tends to “encourage…student[s] to see the text as a fixed piece, frozen in time, that just needs some editing” (Sommers, 1982, p. 151). Though he knew that editing is important for good writing, Basheer decided to prioritize Higher Order Concerns (HOCs) such as audience and purpose over Lower Order Concerns (LOCs) like editing or proofreading. In this way, he tried to construct him as a legitimate writing center tutor who followed current tutoring cultures and practices in writing center communities.

Identity as a Negotiator and a collaborator

Realizing that tutoring also involves working on sentence-level revisions, at times, Basheer shifted his identity to be either a negotiator or a “writing collaborator” (Harris & Silva, 1993, p. 530). When Basheer shifted between these roles, he would either orally suggest revisions or would directly type in revised sentences. This kind of shift was provoked when he sensed the tutee’s struggle in rewording their work. However, each revision was followed by discussion and negotiation until tutees were satisfied with the revised sentences.

In Excerpt 2A, Basheer and Tutee3 worked on her course paper about her experiences with Third Culture Kids (TCKs) or Cross-Cultural Kids (CCKs). Basheer attempted to engage Tutee3 in the discussion of the revision of a paragraph, encouraging her to take action to critically think about her revisions.

Excerpt 2A (Tutorial 3, Tutee 3)

107 BASHEER: do you have something to add

108 TUTEE 3: ah ((saying a sentence to revise her work)

109 BASHEER: yeah we just want to I feel we want to change

110 this parents culture will be American

111 TUTEE 3: okay so # parents should be

112 BASHEER: well pointed or well aware what’s the awareness

113 TUTEE3: be aware of…

114 BASHEER: they understand both parents understand

115 BASHEER: although, we can just put although above # right At the beginning

116 TUTEE 3: right here

117 BASHEER: do you want to say my style maybe or

118 TUTEE 3: you said culture

119 BASHEER: in addition to

120 TUTEE 3: okay

121 BASHEER: and tell me how you feel about this

122 because I don’t want to change the sentence

123 that doesn’t represent [what] you want to say

124 TUTEE 3: [yeah] no I think that sounds better

125 BASHEER: good

126 BASHEER: so how do you feel this first paragraph

127 TUTEE 3: I think that’s fine

In Excerpt 2A, when negotiating with Tutee 3 about how to reword her writing “do you want to say my style maybe or” (line 117), Basheer explicitly explained why he wanted the tutee to reread the sentence that they had revised together “because I don’t want to change the sentence that doesn’t represent [what] you want to say” (line 122-123). Throughout all five tutoring sessions, for each revision or rewording, Basheer always invited the tutees to check to make sure the revised sentence and paragraph represented what they wanted to convey. Basheer preferred tutees to negotiate with him rather than imposed his revisions on them. Furthermore, Basheer welcomed different revisions from tutees; he encouraged tutees to take responsibility for their writing. Discourse like “tell me how you feel about this” constructed him as a collaborator and negotiator of meaning. In addition, Basheer constructed his identity through using “we” (line 109 & 115) rather than “you” when suggesting revision. For instance, “we just want to I feel we want to change” (line 109). By using “we”, Basheer attempted to reduce the distance from the tutee and position himself in the same community with Tutee 3, hence constructing himself as a “writing collaborator” who worked cooperatively with the tutee on her writing.

Identity as a Cultural Ambassador

Being multilingual, Basheer has extra resources from his own culture and unique experiences concerning cultural differences in the United States. When sharing his experiences and cultural knowledge in tutorials, Basheer constructed his identities as a multilingual tutor and a “cultural ambassador” (Fox, 2003). In Excerpt 3, Basheer continued working with the student on her Third Culture Kids assignment. Basheer helped Tutee3 come up with examples regarding cultural shock to support her claim in her paper.

Excerpt 3 (Tutorial 3, Tutee 3)

217 TUTEE 3: should I put a period

218 BASHEER: yeah

219 TUTEE 3: okay

220 BASHEER: for instance for instance comma ((tutor is helping with rewording the sentence))

221 then imagine an example of misunderstanding

222 because of this cultures difference

223 TUTEE 3: okay ah…

224 BASHEER; should I give you one enhen @

225 TUTEE 3: yes

226 BASHEER: I mean I mean coming into US from Middle East

227 TUTEE 3: yeah [yeah that would be] helpful

228 BASHEER: [yeah] I have an issue with greeting people and

229 TUTEE 3: okay

230 BASHEER: you know when I get to talk get to know somebody

231 talk with them like for the first time my name is blabla

232 I come from this country and I am studying this

233 and we seem to be friend and friends and the next day

234 he just say hi and just go like [quickly] whatever you ask

235 TUTEE 3: [right]

236 BASHEER: like it’s for me if we do this back at home

237 if we talk with somebody this close you know

238 like talk for 5 or 6 minutes you know

239 TUTEE 3: yeah

240 BASHEER: the next day would be another longer conversation

241 TUTEE 3: oh…

242 BASHEER; not just saying hi and leaving

243 TUTEE 3: oh

In this excerpt, Basheer performed as a cultural ambassador/broker by informing cultural knowledge to an American tutee (line 226-242). When Tutee 3 struggled with supplying an example concerning cultural clashes in her writing, Basheer offered his own experiences exemplifying how different people from different cultures act with regard to socializing with one another and maintaining their friendship. Basheer intentionally chose to incorporate his multilingual resources into tutorials, thus positioning himself as a tutor with multiple cultural and linguistic repertoire.

In all, Basheer constructed his identity as a writing center tutor, a negotiator, a collaborator, and a cultural ambassador through using language that indexes writing center tutor culture and that indexes his cultural and linguistic repertoire. For example, when tutoring, Basheer chose to focus on rhetorical situation, audiences, and genres before dealing with mechanics or editing because these writing concepts index tutoring culture, beliefs, and values in writing center communities. Through using language concerning these writing concepts, Basheer constructed his identity as a legitimate tutor.

Discussion and Conclusion

During tutoring sessions, Basheer constructed his identities as a writing center tutor, a negotiator and a collaborator, and a cultural ambassador. The identities that Basheer constructed in his tutoring sessions share similarities with those of L1 tutors. For instance, they both act as informants who provide “cultural, rhetorical, and/or linguistic information” (Harris & Silva, 1993, p. 533). However, the multiple identities that Basheer took on in tutoring sessions were not fixed, static, or isolated. Rather, Basheer’s identities were pluralistic, contingent, and dynamic because the interactions between Basheer and tutees were “interactionally contingent” (Scollon, 1995, p. 23), depending on who his tutee was and how their interactions proceeded. Additionally, Basheer’s identities were intertwined and related. Basheer had to shift between his multiple identities in accordance with the immediate and unanticipated responses from tutees. In the writing center, Basheer was only recognized as a tutor. Actually, this “monolithic identity [is] the result of a complex interrelationship between multiple aspects of identity” (Vickers & Deckert, 2013, p. 118) and multiple identities.

Furthermore, Basheer’s identities were co-constructed in his interactions with tutees through the interplay of human agency and social meanings that language indexes. On the one hand, Basheer’s identity construction exhibited agency. He exerted his agency in selecting ways to perform his roles and position himself in relation to tutees by using “we”, which implied closeness and highlighted similarities with tutees. Basheer’s performed his agency when he incorporated his cultural knowledge from his own country during tutoring sessions. On the other hand, Basheer’s identity was mediated by his language and linguistic features which indexed the social meanings of the practices of tutoring culture. Basheer’s discourses pertaining to rhetorical situation and meaning negotiation mirrored and indexed tutoring culture and practices—the priority of cultivating better writers over better writing—in writing center communities which evolve and transform across time and space.

In this study, I attempted to explore what identities an individual multilingual tutor constructed in tutoring sessions. Though the findings cannot be generalized to other multilingual tutors, this study offered insights into understandings of the complex identity construction of multilingual tutors. Multilingual tutors’ identities are co-constructed and evolved (Bhowmik, 2016; Godley & Loretto, 2013) in tutors’ interactions with writing center community members and are shaped by human agency (Schiffrin, 1996) juxtaposing with language-indexed social meanings (Ochs, 1992) that are culturally, historically, and socially situated in writing center communities. Language, indexing social meanings and stances, in tutorial sessions functions as a social practice through which tutors establish their membership and identity as well as maintain and reinforce writing center communities’ values, cultures, and tenets. This perspective benefits writing center administrators, tutors, and tutees regarding their training programs and tutorials. Using language with indexical meanings and stances from writing center communities—focusing on writers’ development, collaboration, and negotiation—can help tutors, multilingual and others, establish legitimate membership as well as help tutees focus on developing their writing ability and take responsibility for their writing.

There are a couple of limitations in this study. First, this study employed merely one method—observation. Though observations allowed me to see what identities Basheer constructed and how his identities impacted his tutoring praxis, they did not manifest what challenges Basheer encountered when he tried to establish his legitimacy in historically monolingual writing center communities. To get richer information, such as perceptions and experiences of tutors and tutees to better understand multilingual tutors’ identity construction, it is suggested that various sorts of data-sets should be collected: interviews, narratives, or videotaped observations to capture non-linguistic features during tutoring sessions. Second, this study only involved one multilingual tutor in one writing center. Consequently, these findings cannot be generalized to other writing centers or other multilingual tutors from diverse cultural backgrounds. Further research could reach more multilingual tutors at various writing centers and should employ diverse methods to collect data to get a more thorough and comprehensive understanding of multilingual tutors’ identity construction, as well as the challenges they may encounter.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Ben Rafoth (Indiana University of Pennsylvania) for his expert advice and comments. I thank the participant in this research for his time and help. I thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Appendix A

Transcription Conventions (Du Bois, 1993)

References

Babcock, R. D. (2016). Examining practice: Designing a research study. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring second language writers (pp. 140-161). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center. New York: Peter Lang.

Bailey, B. (2001). The language of multiple identities among Dominican Americans. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 10(2), 190-223.

Bhowmik, S. K. (2016). Agency, identity and ideology in L2 writing: Insights from the EAP classroom. Writing & Pedagogy, 8(2), 275–309. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1558/wap.26864

Blau, S., Hall, J. & Sparks, S. (2002). Guilt-free tutoring: Rethinking how we tutor non-native-speaking students. Writing Center Journal, 23, 23–44.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth, B. (2016). Tutoring second language writers. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Bruce, S., & Rafoth, B. (Eds.). (2004). ESL Writers. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook.

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2004). Language and identity. In A. Duranti (Ed.), A

companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 369-394). Malden, M.A.: Blackwell.

Chang, T. (2011). Whose voices? perceptions concerning native English speaking and non-native English speaking tutors in the writing center (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Condon, F. (2012). I hope I join the band: Narrative, affiliation, and antiracist rhetoric. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Cox, M. (2016). Identity construction, second language writers, and the writing center. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring second language writers (pp. 53-77). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Cox, M., Jordan, J., Ortmeier-Hooper, C., & Schwartz, G. G. (2010). Introduction. In M. Cox, J. Jordan, C. Ortmeier-Hooper & G. G. Schwartz (Eds.), Reinventing identities in second language writing (pp. xv-xxviii). National Council of Teachers of English.

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Du Bois, J. W., Schuetze-Coburn, S., Cumming, S., & Paolino, D. (1993). Outline of discourse transcription. In J. W. Du Bois, Schuetze-Coburn, S. Cumming & D. Paolino (Eds.), Talking data: Transcription and coding in discourse research (pp. 1-31 and 45-90). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eckert, P., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (1995). Constructing Meaning, Constructing Selves. In K. Hall & M. Bucholtz (Eds.), Gender Articulated: Language and the Socially Constructed Self (pp. 469-507). New York: Routledge.

Fox, C. M. (2003). Writing across cultures: Contrastive rhetoric and a writing center study of one student’s journey (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Friedrich, T., (2014). A “shared repertoire” of choices: Using phenomenology to study writing tutor identity. Learning Assistance Review, 19(1), 53-67.

Godley, A., & Loretto, A. (2013). Fostering counter-narratives of race, language, and identity in an urban English classroom. Linguistics and Education, 24(3), 316-327.

Goffman, E. (1959). Performances The presentation of self in everyday life (pp. 17-76). New York: Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Goodwin, M. H. (1990). He-said-she-said: Talk as social organization among black children. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (Eds.). (2011). Writing centers and the new racism. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Hansen, J. G., & Liu, J. (1997). Social Identity and Language: Theoretical and Methodological Issues. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 567-576.

Harris, M. (1997). Cultural Conflicts in the Writing Center. In C. Severino, J. C. Guerra & J. E. Butler (Eds.). Writing in Multicultural Settings (pp. 220-233). New York: MLA.

Harris, M., & Silva, T. (1993). Tutoring ESL students: Issues and options. College Composition and Communication 44(4), 525-537. http://www.jstor.org.proxy-iup.klnpa.org/stable/pdf/358388.pdf

Hutchinson, G., & Gillespie, P. (2016). The digital video project: Self-assessment in a multilingual writing center. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring second language writers (pp. 123-139). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Jacoby, S., & Ochs, E. (1995). Co-construction: An introduction. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 23(3), 171-183.

Kramsch, C. (2000). Social discursive constructions of self in L2 learning. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 133-153). New York: Oxford University Press.

Leki, I. (1992). Understanding ESL Writers. Portsmouth: Boynton-Cook.

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. London: Routledge.

McNamara, T. (1997). Theorizing social identity: what do we mean by social identity? competing frameworks, competing discourses. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 561-567.

Mehan, H. (1996). The construction of an LD student: A case study in the politics of representation. In M. Silverstein & G. Urban (Eds.), Natural Histories of Discourse (pp. 253-276). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mendoza-Denton, N. (2008). Language and Identity. In J. K. Chambers, P. Trudgill & N. SchillingEstes (Eds.), The handbook of language variation and change (pp. 475-499). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Myers, S. (2003). Reassessing the proofreading trap: ESL tutoring and writing instruction. Writing center Journal, 24(1), 51-70.

North, S. (1995). The Idea of a Writing Center. In C. Murphy & J. Law (Eds.), Landmark Essays on Writing Centers (pp. 71-86). Davis: Hermagoras.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429.

Norton, B., & McKinney, C. (2011). An identity approach to second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 73-94). New York: Routledge.

Ochs, E. (1992). Indexing Gender. In A. Duranti & C. Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking Context: Language as an Interactive Phenomenon (pp. 335-358). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pavlenko, A., & Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Second language learning as participation and the (re)construction of selves. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 155-177). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rafoth, B. (2010). Why visit your campus writing center? In C. Lowe & P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings on writing, volume 1 (pp. 146-155). West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press and the WAC Clearinghouse.

Rafoth, B. (2015). Multilingual writers and writing centers. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Rafoth, B. (2016). Second language writers, writing centers, and reflection. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring second language writers (pp. 5-23). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Schiffrin, D. (1996). Narrative as self-portrait: sociolinguistic constructions of identity. Language in Society, 25(2), 167-203.

Schiffrin, D. (2006). From linguistic reference to social reality. In A. de Fina, D. Schiffrin & M. Bamberg (Eds.), Discourse and Identity (pp. 103-131). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scollon, R. (1995). Plagiarism and ideology: Identity in intercultural discourse. Language in Society, 24(1), 1-28.

Severino, C. (2004). Avoiding appropriation. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), ESL Writers (pp. 48-59). Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook.

Silva, T. (1997). Differences in ESL and native-English-speaker writing: The research and its implications. In J. C. Guerra, C. Severino & J. E. Butler (Eds.), Writing in Multicultural Settings (pp. 209-219). New York: MLA.

Sommers, N. (1982). Responding to student writing. College Composition and Communication, 33(2), 148-156.

Tylor, S. (2001). Locating and conducting discourse analytic research. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. Yates (Eds.), Discourse as data: A guide for analysis (pp. 5-48). Milton Keynes: The Open University.

Vickers, C. H., & Deckert, S. (2013). Sewing empowerment: examining multiple identity shifts as a Mexican immigrant woman develops expertise in a sewing cooperative community of practice. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 12, 116–135.

Wahlstrom, H. (2013). Impostor in the writing center—trials of a non-native tutor. Writing Lab Newsletter, November 1, 10-13.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, J. (2002). Undergraduate second language writers in the writing center. Journal of Basic Writing, 21(2), 73-91.

Zhao, Yelin. (2017). Student interactions with a native speaker tutor and a nonnative speaker tutor at an American writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 57-87.