Jennifer Peña, Florida International University

Nicole Larraguibel, Florida International University

Mario Avalos, Florida International University

Xuan Jiang, Florida International University

Abstract

This position paper exemplifies potential and existing applications of bilingualism, multilingualism, and translingualism in tutoring sessions with support from existing literature and contextual examples from a public state university’s writing center. The authors advocate for the acceptance and incorporation of a diverse range of languages, dialects, and accents in writing and tutoring practices, providing local context to support the development of the writing center as a hub for diversity and a sense of belonging, to the benefit of participating students. Using reviewed literature, this paper examines existing strategies and how they can be applied to a specific writing center environment and describes its broader implications and methods of possible replication in other writing centers. Through a video by a conversation circle facilitator at the aforementioned state university writing center, this paper describes the benefits and means of developing cross-cultural communication skills in the increasingly multicultural and multilingual university context. Further, this paper provides examples of specific strategies used at the writing center, both online and in-person, that spread awareness of a writing center’s multilingual offerings and can be replicated at other writing centers in different regional settings. Combining strategies from literature and the center’s own practices, this paper contributes a unique perspective on the applications and benefits of embracing bilingualism, multilingualism, and translingualism beyond local contexts; other writing center administrators, tutors, and tutoring practitioners alike can incorporate the discussed strategies that are appropriate to the unique linguistic needs of the students at the universities they serve.

Key words: linguistic diversity, inter linguistic, interlinguistic, intra linguistic, advocacy of writing across languages

Introduction

This position paper will discuss how to promote bilingualism, multilingualism, and translingualism in a writing center of, by, and for multilingual students at Florida International University (FIU) who have been insufficiently represented in the university’s curriculum and instruction.

FIU is one of the largest U.S. Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), with over 60% of its undergraduates being Latino/Hispanic (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). The university serves first-generation and low-income students with financial hardships “who otherwise would not have access to higher education” (Lacayo, 2018; U.S. News & World Report, n.d.). It ranked top six in social mobility among national universities in 2018 (EAB Daily Briefing, 2019). In addition to its domestic students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, FIU is a host institution of more than 3500 international students from over 140 countries (Office of International Student & Scholar Services, n.d.). FIU students are constantly being exposed to different languages and cultures through events by student organizations and cultural awareness initiatives, such as conversation circles by the Center for Excellence in Writing (CEW).

The CEW creates contact zones beyond tutoring by offering conversation circles in English, Spanish, and Mandarin for students to utilize and practice languages, which features FIU’s diversity with linguistically fluid dynamics. Such practices and services reflect and promote the local context of multiple languages, dialects, and accents in Miami and aim to cater to all students by respecting, valuing, and providing a space for them to use their own languages and voices. Such recognition and advocacy of bilingualism, multilingualism, and translingualism helps to create a hub that embraces and celebrates diversity, enhances students’ sense of belonging (as an affective filter), and further boosts their academic success.

This paper starts with providing concepts of translingualism, bilingualism, and multilingualism. The paper continues by providing practices of bilingualism and multilingualism, as well as some tutoring strategies for both monolingual and multilingual tutors. The paper then moves on to advocacy and publicity practices of the CEW as an approach to reach out to more students and welcome them into the hub. The inserted video, discussed by the CEW’s Mandarin conversation circle facilitator, echoes some of the aforementioned translingual practices and interprets the conversation circle as a weekly translingual and transcultural activity, as well as its impacts. Last but not least, the paper will discuss possible replication and modification of all the strategies and practices for other writing centers and the rationale behind these strategies.

Bilingualism, Multilingualism, and Translingualism to Restore Justice in WCs

“Writing centers,” Romeo García (2017) cautions, “are not free from power relations” (p. 33). As a symbolic resource in power, languages have been categorized as standard and non-standard. Standard language varieties (e.g. standard American English) help to either create or reinforce “stratification of sociolinguistic resources” (Hornberger & McCarty, 2012, p. 4). In education, standard language ideology entails that “children whose home dialect corresponds to the school standard are automatically exceptional, gifted, and prepared for school, while children who speak nonstandard dialects in the home are automatically rendered remedial, deficient, or underprepared for school” (Carter & Callesano, 2018, p. 69). In the realm of higher education in the U.S., faculty sometimes “fail to acknowledge the Englishes that their students bring into the classrooms as valid and valuable” , “have not kept pace with these 21st-century realities, and persistently display a monolingual orientation more consistent with 20th-century ideologies” (Jain, 2014, pp. 490-1). The term ‘standard’ has been called for reconsideration, such as by Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) in 1974 and the CCCC’s 1974 position statement – “Students’ Right to Their Own Language”, which has been upheld since it was reaffirmed in 2003 (Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2018).

The notion of standard English has been diluted by the practice of translingualism at the CEW. The use of a translingual approach holds the view that difference in languages is not a barrier to overcome or a problem that needs to be managed. Instead, it is a resource to be preserved, developed, and utilized to produce meaning when writing, speaking, reading, and listening. This approach honors “the power of all language users to shape language to specific ends” and recognizes the “linguistic heterogeneity of all users of language both within the United States and globally” (Horner et al., 2011, p. 305). Moreover, it is not used at the expense of learning to write in English; it aims to “build on students’ existing language abilities” instead of replacing “knowledge of one language with another” (Horner et al., 2011, p. 308).

Linguistically, translingualism is a process of negotiation to “decipher and negotiate the shifting boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable linguistic variation” (Williams & Condon, 2016, p. 2). Translingualists draw on resources from a wide range of perspectives, disciplines, languages, and cultures (Kellman & Lvovich, 2015, p. 4). Translingualism calls on monolingual speakers’ openness to linguistic variability (Jiang, Perkins & Peña, 2021, in press) for it to be more commonly accepted and applied as a means of communication that does not abide by the constraints of supposed ‘standard’ forms of a language.

In today’s globalized world, it is impossible to deny the power of the English language, making it a necessary language for many to learn. However, “the power of bilinguals to communicate beyond and across languages and cultures is invaluable” (Alvarez, 2017, p. 97). With extensive vocabularies that go beyond English, multilingual writers have proven to develop meta-cognitive skills to translate and interpret across and between languages, along with producing complex imaginative and critical writing (Alvarez, 2017). It is important to begin appreciating the ability to communicate in multiple languages as a gift that students bring to communities to enrich them.

Strategies in Practice to Be Considered

Rich scholarship in the teaching and tutoring of writing has studied many strategies, which we will discuss in this section with subsections from different angles and in various layers. The detailed narrations include not only the definitions and descriptions of the strategies, but also their merits and shortcomings, if found.

Code-Switching and Code-Meshing

When it comes to practice, code-meshing and code-switching are two typical methods of incorporating translingualism in the writing center field. Code-switching has been defined as the “oral use of two or more languages either within or across sentences … in ways that are syntactically coherent” (Lee & Handsfield, 2018, p. 160). As Canagarajah (2011) notes, code-switching “treats language alternation as involving bilingual competence and switches between two different systems” (p. 403). Code-switching, in our opinion, is a natural product of the linguistic creativity involved in bi- and multilingual language use (e.g. Spanglish in Miami), and so is code-meshing.

Code-meshing involves “mixing vernacular with standard written English … [and] treats the language as part of a single integrated system” (Canagarajah, 2011, p. 403). Code-meshing occurs when multilingual tutors and tutees combine local, vernacular, colloquial, and world dialects of English in daily conversation and in formal assignments. Code-meshing in writing is seen in practice, in particular within sentences, with languages that are intentionally integrated (Lee & Handsfield, 2018, p. 160). Code-meshing allows multilingual tutors and tutees to communicate with a broader audience by combining their native languages (i.e. mostly in Spanish at FIU, an HSI) with ‘standard English’ to pluralize their academic writing and further enhance attained proficiency of their multiple languages.

Inner Linguistic Aspects

Severino and Deifell (2011) focus on applications of English vocabulary by non-native English-speaking (NNES) writers, with particular focus on one writer as an example. Severino and Deifell (2011) argue that “vocabulary concerns move through all levels of discourse” and should, therefore, be regarded as important; they cite prior research by Myers, which finds that L2 writers’ errors tend to be “more lexical than grammatical” (p. 27). The authors maintain that vocabulary is “related to other levels of discourse, to readers’ comprehension and evaluation, and to L2 writers’ ability to function successfully” despite difficulties that may arise from a language barrier at a university that primarily uses English for instruction and writing (p. 49).

With the significance of vocabulary for NNES writers established, Severino and Deifell’s (2011) recommendations for tutors include learning “vocabulary about vocabulary” to better recognize trends, combining in-person and online tutoring, and actively engaging the writer when making corrections to “lexicogrammatical errors” (p. 49). The authors cite Nation’s (2001) book, Learning Vocabulary in Another Language, in explaining such errors as being vocabulary-based but having “a grammatical or syntactic component” (p. 42). The authors maintain that tutors should be prepared to recognize trends in errors to better help NNES writers, in agreement with Nakamaru’s (2010) findings.

Considering the large Hispanic community at FIU, an understanding of the Spanish language can be particularly useful for CEW tutors. Writers who directly translate their work into English from another language may have trends in syntactical issues (Brendel, 2012). Beyond this potential concern, there is the possibility of misunderstandings regarding the uses of English words in different contexts. In some tutoring sessions, especially at HSI-serving writing centers like the CEW, NNES writers may seek help with understanding what the assignment is requiring them to do because of a language barrier. In such situations, writers may expect tutors to explain the assignment instructions in words other than those used by their professors. De la Garza and Harris (2016) find that language learners can more easily build an understanding of “unfamiliar vocabulary” if they are able to construct “mental representations of the text” (p. 397), which can be useful for tutors to understand, especially at writing centers like the CEW that often serve NNES writers.

There are limits to the aforementioned strategy, however; de la Garza and Harris (2016) discuss the possibility for language learners’ failure to understand new vocabulary as a result of “little context in their own language” (pp. 397–398). The findings of the study by de la Garza and Harris (2016) indicate that for “the identification and translation of novel vocabulary terms”, as well as “acquisition for later use”, code-mixing between a language learner’s non-native language and their native language is useful (p. 410), something that would be most plausible for multilingual tutors. This concept is particularly relevant at the CEW, where tutors sometimes have to work around vocabulary-based misunderstandings, and can be associated with Brendel’s (2012) aforementioned idea of contextualizing rhetorical concepts in ways that connect to the writer’s native language to facilitate understanding, a strategy that can be used by tutors regardless of whether they are fluent in a writer’s native language.

Inter-Linguistic Aspects

Transformative Accommodation, a method in which students negotiate language differences using their first language as a resource to write in English, is an effective tutoring strategy to use in writing centers. Liu (2016) illustrates this term by explaining how Angela, a twenty-year-old student from Taiwan, was able to successfully negotiate a space that integrated her “native cultural rhetoric with US academic conventions” (p. 181). When it came to writing, Angela preferred and had a strong basis in Chinese composition. She explained that Chinese composition pays attention to the “Fullness” of the entire article, requires a certain amount of pages, has a specific beginning-transition-turning-synthesis structure, and involves the use of many writing devices to “strengthen the main idea again and again” (Liu, 2016, p. 181). On the other hand, she found English composition required words to be written gracefully, with the main idea expressed as quickly and precisely as possible (Liu, 2016). Now, to include her own writing style in her writing assignments while simultaneously following the professor’s instructions, Angela first identified what the professor wanted: a topic sentence, a main idea, and supporting details. However, for the supporting details, she included her own writing style and Chinese identity by being descriptive in an indirect way. Angela effectively negotiated between English and Chinese writing styles, in a transformational way, by using her well-developed first language knowledge to build up her second language knowledge, helping her gain confidence in learning to write in English while being empowered by using her cultural practices (Liu, 2016).

Another method that can help non-native English-speaking (NNES) students navigate through the complexities of learning to use Standard American English while simultaneously embracing their culture is creating what Mozafari (2009) calls a “Third Space”. It is a “theoretical place where the tutors’ and tutees’ expectations meet and negotiate”, thereby eliminating the common clash of goals and objectives that can occur in a tutoring session (Mozafari, 2009, p. 47). To achieve this “Third Space”, tutors are advised to begin by acknowledging the differences between the NNES student’s text and a standard academic text, along with asking the tutee questions about the cultural motivation, history, and background that led them to produce their paper. Doing so will allow the tutor to better understand the tutees’ writing process in composing their piece. This approach is founded in the existing link between culture and the writing process. When a NNES student becomes aware of the complexities of their culture in relation to the culture they are writing in, their language ability and writing process will improve. Helping a NNES student realize the importance of cultivating successful communicative habits “in their culture and the culture they write to” will give them a purpose: to learn to write with the goal of “giving of themselves, and others like them a place and voice within academia” (Mozafari, 2009, p. 56).

To better illustrate how this method can be put into practice, Mozafari gave the example of a tutoring session he conducted with a twenty-one-year-old Korean student he called Kim, who wrote a paper about American eating habits. Before they began the session, he asked her to “mark the parts of her paper that confused her or the parts where she wasn’t sure if she was being clear” as she read her paper aloud. He reasoned that Kim’s highlights would enable him to better visualize her writing process, the message she was attempting to convey, the weight of her opinions, and how she related herself to the piece.

Mozafari’s approach proved to be effective. When he asked Kim about certain foods she mentioned in her paper, she ended up admitting that she did not know what many of them were despite having written them down anyway. With this in mind, Mozafari used a scaffolding technique that helped Kim feel more confident in her writing process and realize she knew more about the subject than she thought, which effectively placed her in a Third Space. He instructed “Kim to write down, in three columns, what she felt the differences in eating habits were between first Americans, then Koreans, and lastly herself—a Korean living in an American culture” (Mozafari, 2009, p. 58). Having Kim go through this entire process aided her in making connections and recognizing herself within the American population with her Korean identity. She was able to recognize herself in the Third Space without compromising her identity in her paper. Rather, she was able to incorporate it and achieve her goal of writing effectively while using standard American English, an objective NNES students strive to achieve.

Intra-Linguistic Aspects

An existing strategy is to train tutors who do not share students’ native language(s) to identify what kinds of linguistic patterns individual writers carry so as to make the most of their limited time with these writers (Nakamaru, 2010). Nakamaru (2010) described a spectrum of multilingual writers’ needs, ranging between issues with “Language” and “Correctness” (p. 113), categorizing them based on how these writers acquired their knowledge of the English language (p. 108). By dividing multilingual writers into two groups, she identified patterns in the common mistakes of NNES writers, depending on which form of language acquisition (visual or auditory) applies to them (p. 117). Using these groups, Nakamaru differentiated between international students and those who have had prior U.S. schooling, which can lead to varying degrees of exposure to academic texts in English. International students may have had extensive formal instruction on English grammar, which Nakamaru described as learning the language by eye, and they are therefore more likely to include unnatural phrasing in their papers as a result of a lack of vocabulary and rhetorical experience. On the other hand, students with prior U.S. education tend to have learned English through speech, leading to writing that flows naturally (p. 112). Although they often have more experience with academic texts in English than international students do, they tend to have minor errors in their papers, such as confusion between words that sound alike, because of their English-learning method (Nakamaru, 2010).

Further, Brendel (2012) argued that tutors can help writers to form connections between writers’ native languages and English using a strategy he referred to as comparative multilingual tutoring (CMT), in which tutors use their knowledge of languages other than English to the benefits of tutees. As an example, he mentioned a NNES writer that he tutored using this method. Using his limited knowledge of one of her native languages, he explained a rhetorical concept in terms of the other language, thereby forming a lasting connection between languages that the writer would be able to apply in her later writing.

In summary, the terms in the literature review above depict some of the projects that the multilingual tutors at the CEW are doing in the cultivated “Third Space”. The WC’s projects are a manifestation and celebration of diversity in the languages people speak, cultures people bring, and non-academic writing people compose, as showcased through the advocacy and publicity of the CEW.

Advocacy and Publicity of the CEW

While the CEW has internally made strides to better serve FIU’s multilingual student body through the study and application of different strategies and practices, there is still the very real and pressing matter of publicity and advertising. That is, how does a writing center go about marketing the several multilingual undertakings our ambitious student staff has put together?

Establishing an Online Presence

At our writing center, we embrace the many languages and different cultures that our tutors bring to the table. In a school as culturally rich and diverse as FIU, we are proud to have staff members who are fluent in languages ranging from Spanish and Haitian Creole to Portuguese and Urdu. As seen in Figure 1 below, our tutors are asked to write their own profiles for our website, in which they generally mention their academic interests and some personal tidbits of information such as their favorite hobbies. In an effort to make the languages our tutors understand and speak publicly known to the international community of students seeking our services, we urge our tutors to also include their different language proficiencies on their profiles located on the “Staff” page of our website (see Figure 1). The hope, of course, is that students seeking to make an appointment would find comfort in working with a tutor who also has an understanding of their native language. The “Staff” page, as a resource, would help guide these students as they choose a tutor to work with. For instance, Adrian is one of our graduate consultants. In the square photograph, he wears a blue T-shirt and smiles in front of a bookshelf at the CEW. His profile features his field of study, language proficiencies, and “Graduate Consultant” title.

Naturally, our online presence extends beyond our own website, with social media being one of the most formidable tools at our disposal, in terms of advocating our regular services and our more multilingual efforts. The CEW currently holds accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. A small cohort of our tutors, formally called the “Social Media Committee”, split responsibilities related to regular posting and maintenance of our social media accounts.

Perhaps one of the most obvious yet significant benefits of social media comes from the engagement and dispersal of information that it facilitates between our writing center and the students who follow us. Instagram, for one, allows us to continuously remind our followers of our various conversation circles without necessarily having to repeat the same posts by using the Stories feature, which displays a picture on our “Story” for up to 24 hours. Our social media channels also offer students a much more direct line of contact to answer simple questions regarding our services, including appointment availabilities, the nature of and ways to access the conversation circles, and changes to meeting times. Another useful tool that has helped increase our visibility is the tagging feature, which allows other collaborating organizations and entities on campus to tag us in their own posts, consequently expanding our visibility and reach on apps and sites, such as Instagram and Twitter.

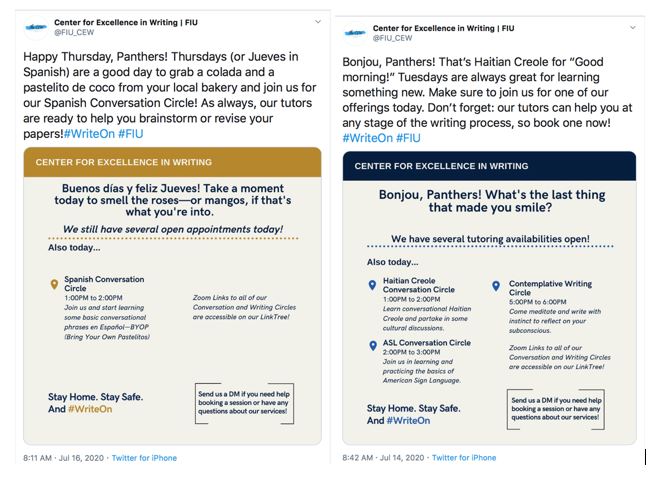

Since our university’s transition to remote learning because of COVID-19 in March 2020, many of our WC’s activities have continued online, including conversation circles. Students are able to access them through links provided in our social media account bios. These links are supplemented by regular posts that list the offerings of the day (see Figure 2). By posting graphics with this information across our social media accounts, we provide a simple and consistent way for students to keep track of our multilingual activities while reminding them of our tutoring services. In the same way, we are able to let students know what offerings are still available to them during their time at home. Such practices can be replicated by other WCs on their preferred social media platforms as well. For instance, the screenshots in Figure 2 below display Tweets posted on our Twitter page, which incorporate the school colors of Gold and Blue and highlight our recurring weekly writing and conversation circles, which are open to all students. Under the account name (@FIU_CEW) and logo that reads “The CEW”, the graphics feature crucial information such as the names of the events, meeting times, and short one-sentence blurbs that explain what attendees might expect from each session. The graphics also incorporate the hashtag #WriteOn, which is a mantra used throughout our different social media channels and printed on the back of our staff shirts.

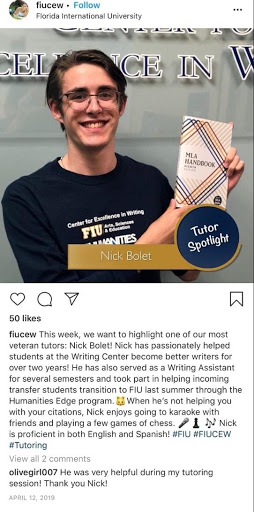

Beyond marketing our center and its services at large, we have found social media to be not only a potent outlet to market our upcoming workshops/events in addition to our regular tutoring services, but also a space where we can highlight our tutors and the aspects that make them unique. Late in the Spring 2019 semester, the Social Media Committee began an initiative to highlight different participating tutors through their bi-weekly “Tutor Spotlight” posts in an effort to synchronically deliver information about our tutors that often includes their language proficiencies to cater for students’ linguistically diverse needs, as seen in Figure 3 below. The photograph shows Nick, a writing center tutor. He stands in front of a sign in the CEW lobby, holding the MLA Handbook with a smile. The text provides a description of Nick’s hobbies and qualifications, including past work experience and language proficiencies.

The Importance of a Physical Presence

While a strong presence on social media is key to any kind of publicity efforts, a substantial physical presence on campus to match cannot be understated. Our writing center has long participated in classroom visits at the request of different faculty members who are already familiar with our services and interested in the positive impact our services would bring to the work and writing processes of their students. Class visits will generally involve a pair of tutors dropping in during the early or late part of a class meeting, where they talk about the center at large, offer demonstrations of how to make an account and an appointment on our website, and answer any questions students might have. Tutors discuss a given semester’s available activities, often including the various conversation circles in multiple languages, thereby reflecting and catering to student demographics.

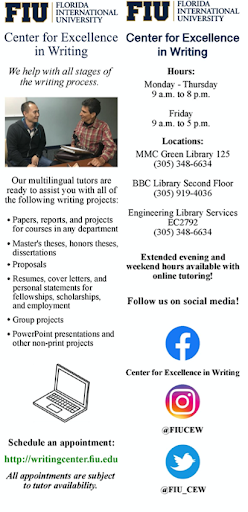

Tutors also make it a point to hand out copies of our bookmarks (see Figure 4), which contain several of the most pertinent bits of general information about us, as well as our contact information, so that students interested in using our services have some point of reference that stays with them beyond the limited in-person interaction. Our bookmarks also make mention of our multilingual tutors and provide a hyperlink which students can follow to find out more on our website. The figure below shows the front and back sides of the CEW bookmark. On the front side, the purpose and uses of the writing center are listed. An image shows a tutor and a student smiling at each other as they sit together at the CEW. At the bottom, there is a laptop symbol. Under the symbol, the CEW’s website URL is provided under the words “Schedule an appointment”. On the back side of the bookmark, the CEW’s hours, phone numbers, and locations across FIU’s different campuses are listed. At the bottom, the CEW’s social media account names are printed underneath the symbols of social media platforms, as follows: “Center for Excellence in Writing” for Facebook, @FIUCEW for Instagram, and @FIU_CEW for Twitter.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, class visits became virtual. Usually, a tutor will join an interested professor’s remote class meeting to discuss our services, including showing students our staff page and activity pages. This way, students are made aware of their ability to access tutors of different backgrounds and linguistic skills through online tutoring, as well as our center’s other multilingual offerings, many of which have continued virtually as well.

Among the several services tutors make an effort to touch on during these visits, our various multilingual offerings such as our English Conversation Circle, Spanish Conversation Circle, Mandarin Conversation Circle, and Creative Writing Wordshop are often at the forefront of the offerings students have the most questions about. The video below talks about the Mandarin Conversation Circle and how that event enhances students’ awareness of linguistic multiplicity and cross-cultural communication skills.

TRANSCRIPT – Multilingualism Video

Because a significant portion of our class visits take place in First-Year Composition courses (ENC 1101 & ENC 1102) made up of a diverse assortment of freshmen students, class visits have proven to be one of our most recurring and effective methods of reaching FIU’s broad multilingual student body. Worth noting is that one of the most frequent questions asked of tutors is how to go about applying for a position at the writing center. While class visits are meant to inform students about our services, they have also come to be complementary in keeping students aware that our center is also a place they might work, securing a healthy influx of prospective multilingual and multicultural tutors from varying majors that sign up to take our peer tutoring preparation course: ENC3491—The Processes of Writing.

Similarly, in recent years, we have made strides to increase our visibility around campus through other means. Tabling (see Figure 5), for instance, has been a successful manner of establishing a more consistent and visible presence on campus. Whereas classroom visits are often conducted at the behest of faculty members, tabling sees a rotation of tutors setting up shop at the Graham Center (GC)—our university’s community center and one of the most active buildings on campus, given its centralized location. Our tutors prepare several copies of flyers with information on our different offerings, including our various conversation circles and writing circles. Participating tutors also take several blank sign-up sheets, which students then fill out with their names, student ID numbers, and emails to be added to our mailing list, which enables them to receive updates regarding our center. In Figure 5 below, three CEW tutors sit in front of a large fish tank at a table adorned by a dark blue tablecloth with “FIU” and “Center for Excellence in Writing” printed on the front. A sign above them reads “FIU Graham Center”. Small stacks of bookmarks (see Figure 4) and flyers for various writing center activities are displayed on the table. A flyer advertising various conversation circles stands in a plastic holder atop a stack of books on one side of the table. The tutors on the left and right have neutral expressions and wear black long-sleeves. The tutor on the right holds a pen to paper, as if writing. The tutor in the middle wears a dark blue CEW T-shirt and smiles.

The Advantages of Collaboration

It was noted earlier how the tagging feature on Instagram and Twitter has been a useful way of increasing our visibility across campus. While there might be times when students will tag us in posts uploaded onto their personal pages, collaborations on campus have proven to be effective in follower acquisition. Our writing center is always open to collaborate with organizations such as the Student Programming Council (SPC), which often hosts large-scale events with several entities across campus in an effort to familiarize students with all of the services that are available to them at no charge. One of the most fruitful and on-going collaborations our center has cultivated is one with the Panther Film Festival (PFF), the student-led film festival on campus.

The film festival itself is already a collaborative effort between the Film Initiative Underground (FIU’s film club), Sigma Tau Delta (the English Honor Society), and the Film Studies Certificate Program, which is offered by the Department of English. Dating back to the first iteration of PFF in 2018, our writing center has often collaborated with Dr. Andrew Strycharski and the other minds behind the festival by providing our meeting room as a space for screenwriting workshops that are advertised and marketed not only on our own social media, but also on those of the other involved organizations. Over the years, these opportunities have often resulted in several students making their way into the writing center for the very first time and allowed the tutors leading these workshops to introduce and talk a little about our services before proceeding with the actual planned activities.

Replication and Modification – Why and How?

To consider how the CEW’s practices can be replicated at other writing centers, it is important to first acknowledge the linguistic and cultural contexts of the university that it serves. FIU primarily serves working-class and minority students and thus has had a large impact on social mobility in local communities in South Florida. FIU has over 56,000 enrolled students, including over 40,000 undergraduates and over 4,000 degree-seeking international students. The student demographics are 61% Hispanic, 15% White, 13% Black, 4% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 7% Other. FIU’s diversity, as represented by its writing center staff, mirrors its local context—Miami-Dade County. The county is one of the most Spanish-speaking metropolitan regions with one of the largest Latinx populations in the U.S. (Brown & Lopez, 2013). It is a multicultural and multilingual hub that more U.S. cities will resemble in the years to come (Carter, 2018).

Hence, CEW directors, along with many others in the U.S., have introduced and celebrated diversity of languages in their center’s tutoring practices and beyond (Cui, 2020; Hutchinson & Gillespie, 2016) via deployment of tutors’ linguistic multiplicity and transfer (Cui, 2020; Zhao, 2017). Such a practice resembles the locality of FIU—very often, the university environment sees bilingual and multilingual tutors and tutees “of diverse backgrounds on all sides of the tutorial table” (Hedengren, 2018, para. 7) and represents the future of universities in the U.S.

With that said, tutoring staff at writing centers nationwide can prepare for contexts in which they will work with an increasing number of multilingual writers. As mentioned in a previous section, research by Nakamaru (2010) describes a method of tutor training that equips tutors to work effectively with NNES writers depending on whether they acquired the English language by using visual or auditory methods. Nakamaru’s spectrum of multilingual writers’ needs can be incorporated in tutor training courses as a means of preparing tutors to recognize patterns when working with such writers, which can be useful to tutors even if they are not fluent (to any extent) in the NNES writers’ native languages.

When working with multilingual writers, Nouf Alshreif (2017) recommends for non-multilingual tutors to use invitational rhetoric to “help establish trust and emphasize confidence”, such as by “listening in the sense of not interrupting when tutees are sharing their experiences” (para. 13–14). Invitational rhetoric, according to Alshreif, is a way to “emphasize the values of shared relationships and understanding as power”, which in turn allows tutors to “support the perception of difference as an opportunity” (para. 16). With this in mind, tutors can build rapport with multilingual tutees and encourage NNES writers to embrace the differences between their native languages and English in their writing. While rapport can sometimes occur naturally, future CEW tutors also learn from the strategies of current tutors by observing tutoring sessions as part of the center’s tutor training course.

Further, as mentioned earlier, Brendel’s (2012) CMT can be applied in writing centers in which non-multilingual tutors often work with linguistically diverse writers. In these contexts, the writing center staff can strive to reflect these writers’ needs by seeking to understand rhetorical concepts of their tutees’ common native languages. In doing so, they can contextualize concepts of the English language for these tutees (Brendel, 2012). Without needing to be fluent or even proficient in languages other than English, tutors can aim to understand the structures of other languages to better serve their multilingual clients, perhaps as a form of professional development for the writing center staff.

Conclusion

The position paper has demonstrated successful practices to embrace linguistic diversity and reviewed literature to show some evidence-proven strategies and approaches. The paper has used the strategies of FIU’s CEW as examples of how to reach a broader student audience and cater to students’ linguistic needs. The authors strongly believe that these practices can be replicated and modified for wider use in the writing center field and other academic contact zones in higher institutions.

References

Alshreif, N. (Spring 2017). Multilingual writers in the writing center: Invitational rhetoric and politeness strategies to accommodate the needs of multilingual writers. The Peer Review, 1(1).

Alvarez, Steven. (2017). Official American English is best. Bad Ideas About Writing, West Virginia University Libraries, pp. 93–98.

Brendel, C. (2012). Tutoring between language with comparative multilingual tutoring. The Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 78-91.

Brown, A., & Lopez, M. H. (2013). Mapping the Latino population, by state, county and city (pp. 53098246-2). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Canagarajah, S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 401-417.

Carter, P. M. (2018). Hispanic-serving institutions and mass media engagement: Implications for sociolinguistic justice. Journal of English Linguistics, 46(3), 246-262.

Carter, P. M., & Callesano, S. (2018). The social meaning of Spanish in Miami: Dialect perceptions and implications for socioeconomic class, income, and employment. Latino Studies, 16(1), 65-90.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. (2018, June 16). Students’ right to their own language (with bibliography).

Cui, W. (Winter 2020). Identity construction of a multilingual writing tutor. The Peer Review, 3(2).

de la Garza, B., & Harris, R. J. (2017). Acquiring foreign language vocabulary through meaningful linguistic context: Where is the limit to vocabulary learning?. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 46(2), 395-413.

EAB Daily Briefing. (2019, July 18). The top 18 colleges for social mobility, according to US News.

García, R. (2017). Unmaking gringo-centers. The Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 29-60.

Hedengren, M. (Fall 2020). An empirical study of non-native English speaking tutors in the writing center. The Peer Review, 2(2).

Hornberger, N. H., & McCarty, T. L. (2012). Globalization from the bottom up: Indigenous language planning and policy across time, space, and place. International Multilingual Research Journal, 6(1), 1-7.

Horner, B., Lu, M.-Z., Royster, J. J., & Trimbur, J. (2011). Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English, 73(3), 303–321.

Hutchinson, G., & Gillespie, P. (2016). The digital video project: Self-assessment in a multilingual writing center. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring second language writers (pp. 123-139). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Jain, R. (2014). Global Englishes, translinguistic identities, and translingual practices in a community college ESL classroom: A practitioner researcher reports. TESOL Journal, 5(3), 490-522.

Jiang, X., Perkins, K. & Peña, J. (in Press, 2020). Transnationalism contextualized in Miami: The proposed component of dialectal Spanish negotiations in undergraduate TESOL courses. In O. Barnawi & S. Anwaruddin (Eds.), TESOL teacher education in a transnational world. Routledge.

Kellman, S. G., & Lvovich, N. (2015). Literary translingualism: Multilingual identity and creativity. L2 Journal, 7, 3-5.

Lacayo, J. (2018, May 3). Climbing the socio-economic ladder: FIU graduates go further.

Lee, A. Y., & Handsfield, L. J. (2018). Code-meshing and writing instruction in multilingual classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 72(2), 159-168.

Leonard, R. L., & Nowacek, R. (2016). Transfer and translingualism. College English, 78(3), 258-264.

Liu, P. H. E. (2016). These sentences sounded like me. In S. Bruce & B. Rafoth (Eds.), Tutoring Second Language Writers (pp. 180–185). Utah State University Press.

Mozafari, C. (2009). Creating Third Space: ESL Tutoring as Cultural Mediation. Young Scholars in Writing: Undergraduate Research in Writing and Rhetoric, 6, 47–59.

Nakamaru, S. (2010). Theory in/to practice: A tale of two multilingual writers: A case-study approach to tutor education. The Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 100-123.

Nation, I.S.P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Florida International University Enrollment Survey (College Navigator).

Office of International Student & Scholar Services. (n.d.). The Office of International Student and Scholar Services (ISSS) welcomes all international students at FIU! Retrieved from https://globalaffairs.fiu.edu/isss/.

Severino, C., & Deifell, E. (2011). Empowering L2 tutoring: A case study of a second language writers vocabulary learning. The Writing Center Journal, 31(1), 25-54.

U.S. News & World Report. (n.d.). How Does Florida International University Rank Among America’s Best Colleges?

Williams, J., & Condon, F. (2016). Translingualism in composition studies and second language writing: An uneasy alliance. TESL Canada Journal, 33(2), 1-18.

Zhao, Y. (2017). Student interactions with a native speaker tutor and a nonnative speaker tutor at an American writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 57-87.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the consenting tutors for the permission to use their photos. We also thank Dr. Glenn Hutchinson, Dr. Vanessa Kraemer Sohan, Mr. Charles Donate, and Mr. Manuel Delgadillo (Florida International University) for their advice and comments. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.