Janel McCloskey, Drexel University

Mary Allain, Drexel University

Sarah Drepaul, Drexel University

Kelsey Hendry, Drexel University

Janae Kindt, Drexel University

Aaliyah Sesay, Drexel University

Devin Welsh, Drexel University

Abstract

Calls for antiracist pedagogies in university writing programs have gained attention and momentum in recent years. Many BIPOC scholars, and some white scholars, have been making arguments for more equitable university writing instruction and writing ecologies for decades. Yet, conditions have largely stayed the same. Undoing systemic racism in our institutions, programs, and ourselves is an individual and communal process that requires commitment and action. In this article, the authors describe a multiyear engagement with Equity-Centered Community Design, a framework offered by Creative Reaction Lab, that facilitates the process of seeing and recognizing systemic racism as intentionally designed to produce outcomes, so that what is designed may be dismantled and redesigned for equity. The multimodal composition of the article aims to convey the fluid, dynamic, and embodied process of doing this work that goes deeper and reaches farther than more typical writing center and writing program work. The goal is to offer a tool to writing centers, writing programs, departments, colleges, and beyond for turning antiracist support into antiracist realities.

Keywords: Equity-Centered Community Design, antiracist pedagogy, writing centers, writing programs, design, equity

Below is the preferred composition of this article. Please click in the in top right corner to open in a new tab and view as intended.

Introduction

I began antiracist work in the writing center after many years of an internal reckoning with racism. My struggle to understand race and inequality, to try to see what whiteness makes invisible, to understand how and when to give up privilege, or to wield it to increase equity, is a lifelong process of engagement. How to move from despair to action, aside from uncomfortable conversations with family and friends, became more clear as I came into awareness of what Ta Nehisi Coates calls, “the Dream of living white” (2015, p. 60). The Dream is a false reality, a mirage, that white people are conditioned to see as the real world. It envelops us in blissful ignorance of the structures upon which America, and our lives, are built. The fact that this American Dream of self-determination and individual achievement is built on the theft of labor and lives of BIPOC—and is sustained through the systemic denial of the rights, resources, opportunities, and humanity of people of color—is made invisible to white people by our very belief in a the Dream. For white people, it takes work to see the structures that confer privilege and dish out oppression, but the real work is in dismantling those structures.

When I assumed directorship of the Drexel Writing Center (DWC) in 2015, I saw the opportunity to engage in that work. It was a about a year and a half after Michael Brown was gunned down in Ferguson, Missouri and it seemed like news of black people being killed by law enforcement was constant. The police brutality and racial violence people of color had always experienced in America was surfacing in a more visible way. Activist groups like Black Lives Matter were breaking through the veil of whiteness, pulling hands away from our eyes and fingers out of our ears so that we must see and hear the pain and struggle all around us. Race was in the national consciousness in a way I had not seen before in my lifetime.

In “Making Our Commitments to Racial Justice Actionable,” Rasha Diab, Thomas Ferrel, Beth Godbee and Neil Simpkins (2013) remind us that our job is to ”teach more than reading and writing as techné” but also to “strive to invest in citizens who can participate in and enrich deliberative democracies” (p. 5). It is impossible to do this while upholding programs and policies that reproduce inequity. The global is local, the personal is political. But it’s also more simple than that. If I want to Iive in the light of truth, I cannot operate in these systems without trying to make them visible and to engage in the work of breaking them down.

In preceding years, my colleagues and I had created a strong training and professional development program in the writing center that was fertile ground for engaging in antiracist pedagogy. Our program, like many, lends itself easily to this work through engaging students in critical reading, reflective writing, and interrogation of the self as writer, reader, and thinker. I began with an awareness of my limitations in antiracist work as a white, middle-class, cis-gender woman. I embraced the inevitable missteps and mistakes I would make along the way and welcomed the opportunity to do better. Much of this work involved decentering my own voice and centering the voices of BIPOC. I could trust that the program provided the peer readers with the basic tools they needed to engage in this work in the three contexts that it must occur: individually, in community with each other, and in the institution.

In the beginning, there was a lot of resistance and white fragility. Exposure to linguistic truths and standard language ideology seemed to make students who had spent much of their academic career attempting to master Standard Academic English (SAE) waver between feeling duped and feeling unmoored. We struggled with the ways this work disrupted foundational ideas about writing, education, equality, what is earned and what is an outcome of systemic racism. As the ground shifted beneath them, tutors moved from clinging to white racial norms, like standard language ideology, to embracing a broader vision of what is “normal” and for whom. The students developed a spirit of activism, a desire to take down the system, and expressed a deep frustration infused with an eagerness to “end racism.”

As a community, we were still seeing through the lens of “…the ways we are trained to see ‘the racist’ as the other, the few, and the obscure rather than thinking of ‘racism’ as very much our own and embedded in all our everyday interactions” (Diab et al. 2013). We were very much “stuck in the realm of the problem” and failing to move “toward articulations of our commitments or considerations of what ought to be” (Diab et al. 2013). Tutors needed the occasion and context to engage deeply in the internal work of recognizing how racist systems have acted upon them, their peers, and their communities.

In moving beyond thinking of racism as discreet acts, Peer Readers still saw systemic racism as residing somehow outside of themselves. They were resisting feelings of complicity and pain, resisting seeing and acknowledging racism inside their own belief systems, perceptions, pasts, present, and futures.

Diab et al. discuss the process of both making commitments to racial justice through dialectal practices and making those commitments actionable. One of the mistakes I made was in working toward goals that came out of my own commitments to racial justice. Peer Readers needed to choose to make their own personal commitments to racial justice. Inspired by Asao Inoue’s work in the writing center at the University of Washington, Tacoma, the Peer Readers collaboratively wrote the Statement of Antiracism in the Drexel Writing Center that articulated our commitments to antiracist work. The statement came out of a multi-year process of researching, reading, writing and talking about systemic and institutional racism and linguistic diversity.

Writing the Statement of Antiracism in the Drexel Writing Center ironically brought up a sort of abdication of agency as Peer Readers struggled with the conflict between their commitments and institutional attitudes and practices that uphold white racial norms. They threw up their hands in frustration claiming that faculty would never allow linguistic diversity to function in academic spaces.

Antiracist work is messy and does not happen in a linear fashion. It often feels less like progress and more like moving backwards, in circles, stops, and starts as we continually see that we are a part of the systems we oppose. We had articulated our commitments; we had not fully reckoned with how systemic racism had shaped each one of our lives, how it cradled some of us and choked others, or how to reclaim agency.

To make change, we needed to see not only racist structures, but their intentional design and outcomes. Diab et al. (2013) cite the work of Horton (1997), Mathieu (2005), and others in stating that “it’s not enough to engage just in a ‘critique of’ or ‘action against’ racism (or stances that make us complicit), but rather we need a positive articulation of ‘critique for’ and ‘action toward’ to keep our eyes on the ought to be” (p. 6). In order to make commitments to racial justice actionable, as Diab and et al. so eloquently describe, we need to understand our own place and power to redesign systems and structures to produce equity.

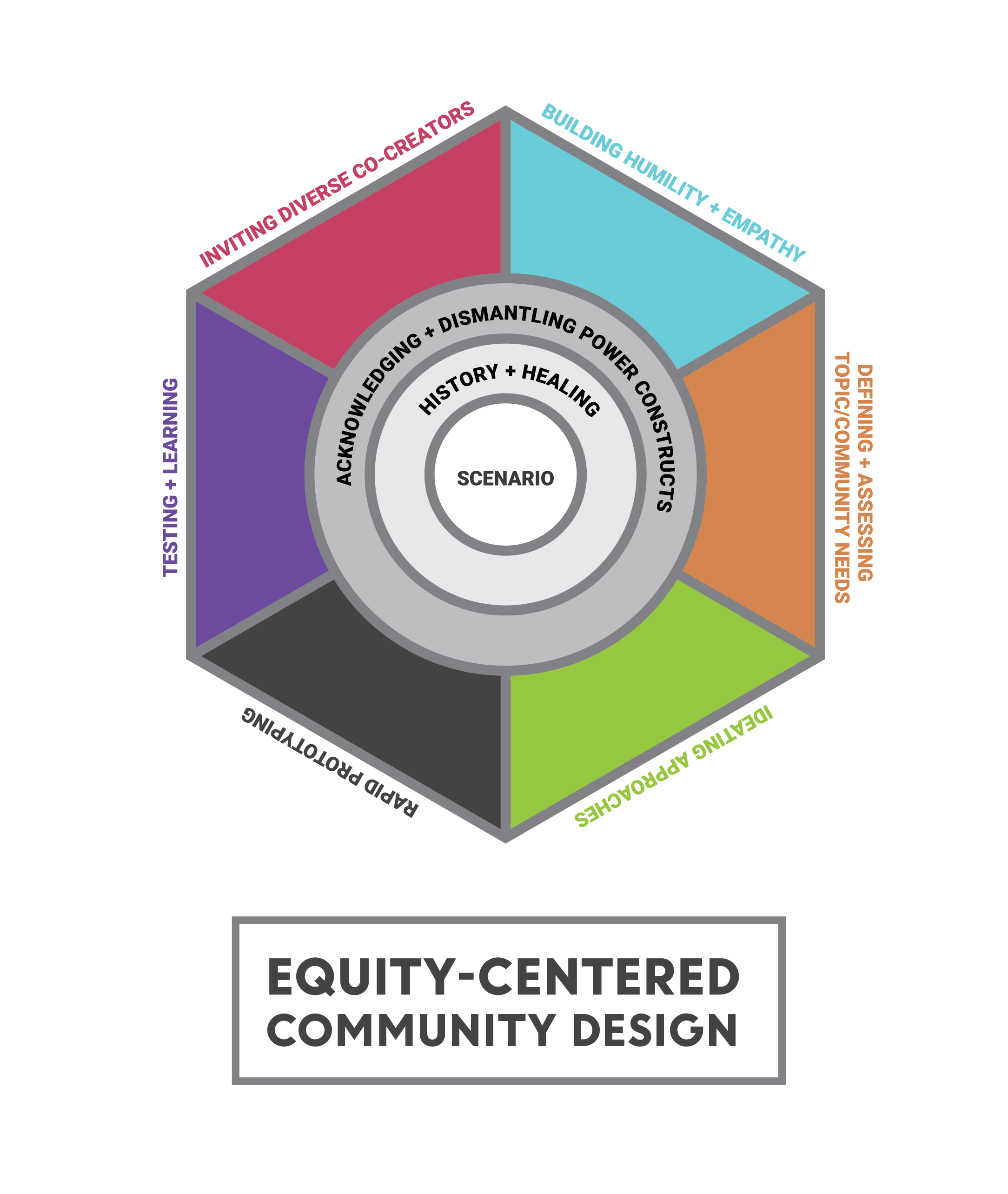

This is where we turned to the work of Creative Reaction Lab, a nonprofit organization founded in support of the uprising in Ferguson Missouri. They offer Equity-Centered Community Design (ECCD) as a process for problem solving based on equity, humility-building, integrating history and healing practices, addressing power dynamics, and co-creating with community (Field Guide: Equity-Centered Community Design, 2018, p. 3). ECCD is targeted at five sectors of society: education, government, media, healthcare and public health. It operates on the premise that systemic racism was intentionally designed, and its outcomes are according to that design. Anything that is designed can be redesigned and anyone who has the ability to make a decision, no matter how small, is a designer (FG:ECCD, 4).

The iterative, nonlinear process of this framework was the tool we needed to move from thought to action through individual work, communal work, and institutional work. ECCD provided a process for operationalizing the foundational understanding that inequity exists by design and intentional acts can dismantle systems of inequity. ECCD (2018) defines a designer as, “…anyone who has agency to make a decision, however small, that will impact a group of people or the environment “ (FG: ECCD, p.4). The process creates the frame I was seeking for Peer Readers to recognize and claim their own agency, to see that they were not helpless pawns in a system, but part of that system with the agency to change it. This small realization, that each of us has agency to create change, was pivotal.

In this article, we will describe how we worked with the framework to redesign our writing center around equity. I will describe the process and the ongoing and overlapping phases of our work with it. Peer Readers Mary Allain, Sarah Drepaul, Joseph Kindt, Aaliyah Sesay, and Devin Welsh will give voice to our progress toward equity as well as the difficulties and conflicts we continue to have. Our goal is to introduce you to the Equity-Centered Community Design Field Guide as a flexible tool that makes antiracist work replicable in writing centers and programs, a tool that can be adapted to the many varied contexts of writing centers and writing programs. While writing programs can be central in shaping the identity of students, they have also been central in erasing identities and perpetuating systems of inequality. We hope ECCD can help fulfill the potential of writing centers and programs to recognize their agency in redesigning for equity.

What Is Equity Centered Community Design?

The Equity-Centered Community Design Field Guide was developed by Creative Reaction Lab, a nonprofit organization formed in 2014 in support of and response to the uprising in Ferguson after Michael Brown, Jr. was killed. Their mission is to “educate, train, and challenge Black and Latinx youth to become leaders designing healthy and racially equitable communities” (The Ferguson Uprising Was Only Just Beginning, 2020).

Equity-Centered Community Design is rooted in this foundational belief:

The reality of our society is that any system produces what it was designed to produce (unless a stronger force intervenes). Therefore, if oppression, inequalities, and inequities are designed, they can be redesigned. As we strive for human equity, we have to be able to recognize inequity and have the ability to recognize ourselves as designers who have the power disrupt it. (FG:ECCD, 2018, p.8)

ECCD acknowledges and utilizes the role of people + systems + power in developing solutions or approaches that impact the many within different communities (FG:ECCD, 2018, p.1). A key understanding of ECCD is that a designer is, “anyone who has agency to make a decision, however small, that will impact a group of people or the environment. Every decision we make has an impact on equity” (FG:ECCD, P. 4).

ECCD’s reframing of IBM’s mantra, that design is the intention behind an outcome, to include that it is also the unintentional impact of an outcome was an essential way for Peer Readers to understand systemic racism in the everyday practices of the writing center. We may not intend to reinforce systemic racism through enforcing standard language ideology but that is what the system is designed to do. Seeing ourselves as designers with the ability to make decisions that impact others allows us to see our own agency, our own power within the system.

All of our work with ECCD began with Things to Remember and Community Agreements. These laid the ground rules for working together and respecting the various backgrounds and perspectives represented.

Leaning into discomfort became an overarching theme in our work, a frame for how we can think of restorative justice in the writing center and university, as articulated by Peer Reader, Janae Kindt:

In the writing center and the university, standard English expectations create difficult dilemmas that tutors are must confront to reach a sense of restorative justice. When we’ve examined the power structures of the university, we’ve concluded that professors and administrators who are proponents of standard English perpetuate linguistic injustice, whether they do so wittingly or not. Since we understand the deeply personal, internal work required of an equity centric community, talking about effecting change in the university often ends up focusing on how we can reach professors and bring antiracist pedagogy into their personal practice.

In practice, when working with different students’ varieties of English, we’re faced with the moral dilemma. Is it right or wrong to help them “standardize” their work for the sake of their professors grading criteria? To us, an image of restorative justice that resolves this dilemma might look like a professor focusing on the clarity of the student’s writing and the natural flow of their ideas—not an idea of “correct” English. The voice in our heads as we compromise our ideals wishes it could reach that professor and invite them to engage with our work in antiracism.

The reality of this dilemma, however, is uncomfortable. As tutors practicing from the foundations of Equity-Centered Community Design, our task is to lean into that. However, correcting grammar meets our desires as students (we who hunger for good grades) by satiating the need for “high marks” in otherwise quality writing.

We can, however, evoke change in each individual we encounter by leveraging humanism to lean into the discomfort we face as tutors in sessions (because race is, essentially, present in every session we’ll conduct). We can enter sessions mindful of race, knowing that race can and will show up. Leaning into discomfort when race shows up in a session can be as simple as asking a student how they feel about their work, what is stressing them out about their assignment.

If the answer is something along the lines of “my professor’s comments,” and those comments look like “grammar and conventions,” the light for a quick conversation about linguistic diversity is glaringly green, y’all. We have all dealt with the anxiety of writing to meet the mythical “standard of English,” and can constructively utilize empathy to bridge our understanding of antiracism into the work of our peers.

And maybe the conversation fizzles out fast. But maybe you have a substantive conversation with your peer and both of you leave the session changed in subtle ways. When we tackle as massive an undertaking as restorative justice in our center, we can’t forget the value of small impacts.

The Field Guide approaches each step with an overview of what it is about, tips for approaching and applying each step to different contexts, sample activities to practice steps, and space for reflection. Often these steps are overlapping, recursive, and connected.

Inviting Diverse Co-Creators

Image 2 – Clasped Hands, Tim Mossholder – This image shows two hands clasped together. The hands and background are multicolored with vivid hues.

Inviting Diverse Co-Creators focuses on bringing in the diverse knowledge bases, perspectives, backgrounds, and insights of the community. This enables a holistic approach to building an understanding of the community, the problem-solving process, and implementation of solutions. An especially important part of this process is including what ECCD calls “living experts,” the people and communities often excluded from decision-making processes who are also often the most affected by the decisions made (FG:ECCD, 2018, P.15).

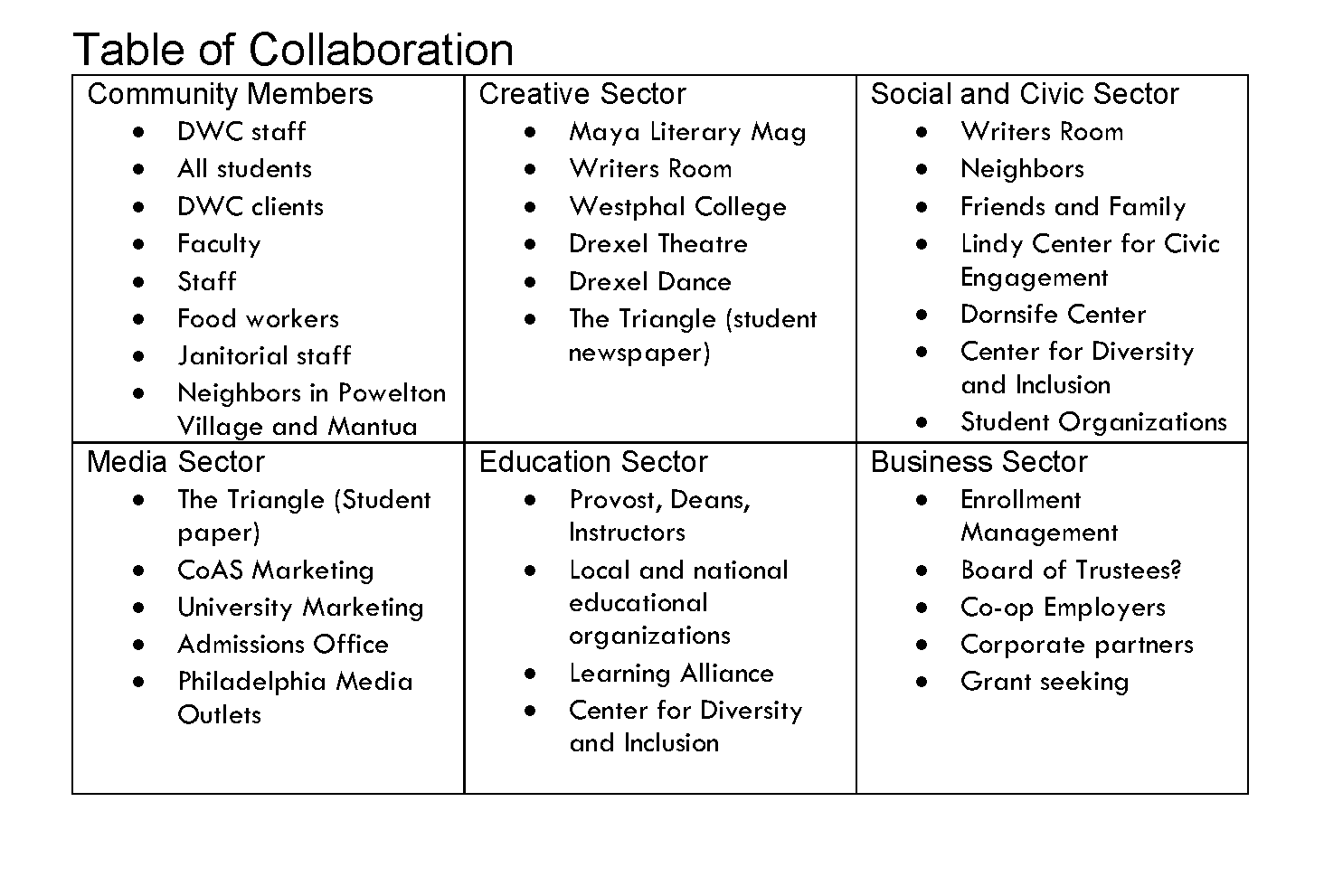

To engage the Peer Readers’ perception of their lack of agency, I asked them to imagine themselves as designers with the power to bring anyone to this work. The resulting table of collaboration looked like this:

The Field Guide offers tips and guidance for reaching out to co-creators identified in this process and building relationships to productively collaborate in the ECCD process.

We discussed the specific expertise and insight each partner might bring to the table, considered who could benefit and how to make interactions mutually beneficial.

In deciding how to move forward, we strongly considered barriers to participation and where decision-making power lies. We identified student writers, particularly students of color, as the living experts in our community. Any initial efforts at inviting co-creators would focus on students. Building on the relationships we already had with student writers in sessions, we also added a question to our post-appointment survey that invited their participation in ECCD.

As the director of the writing center, I have some power to reach other institutional audiences. My efforts created relationships that resulted in work with the Lindy Center for Civic Engagement, an article about the writing center’s work with antiracism (featuring Peer Readers), and workshops on antiracist pedagogy (focusing on language equity) with faculty and staff. Small steps, but steps nonetheless.

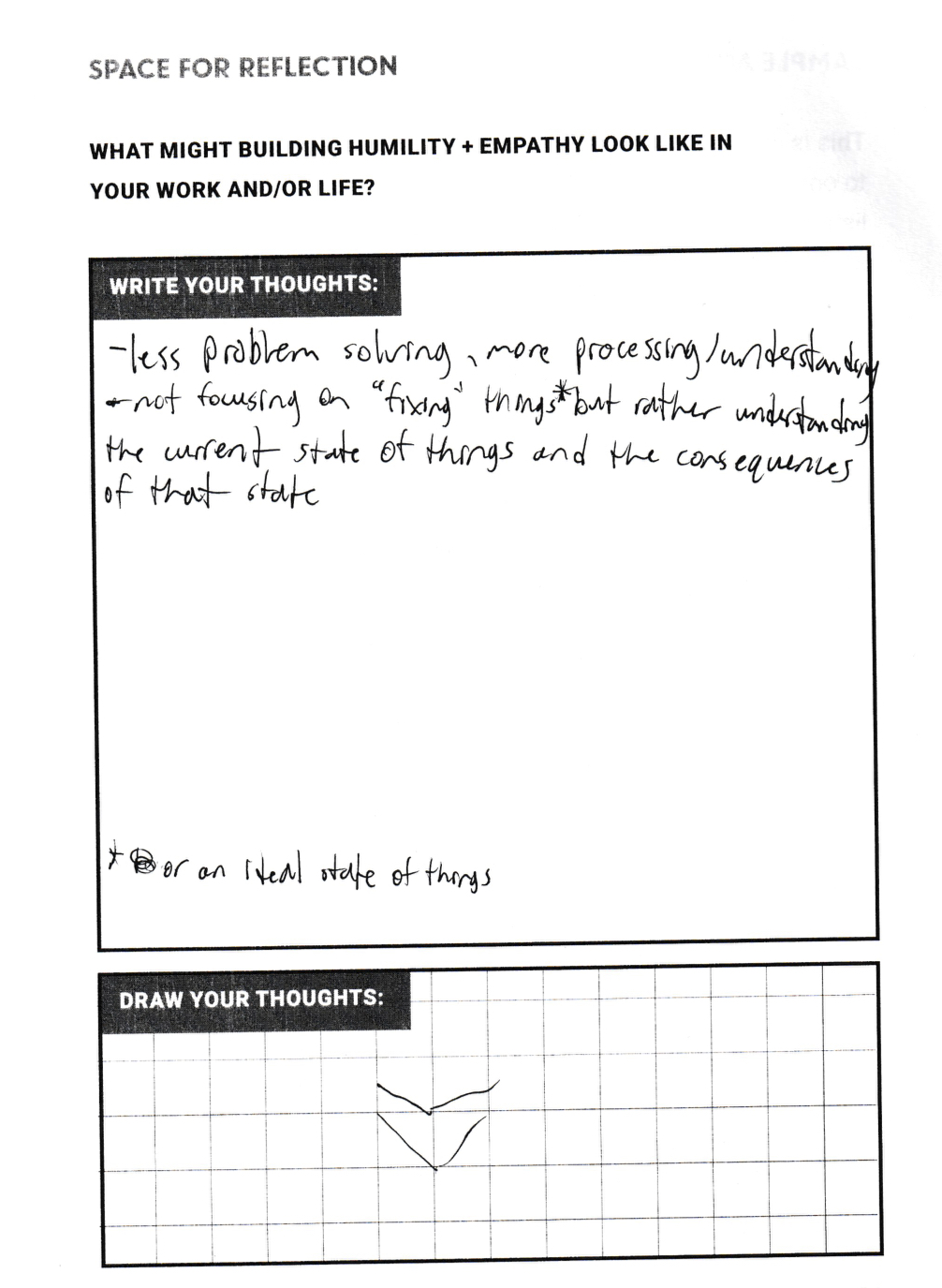

Building Humility and Empathy

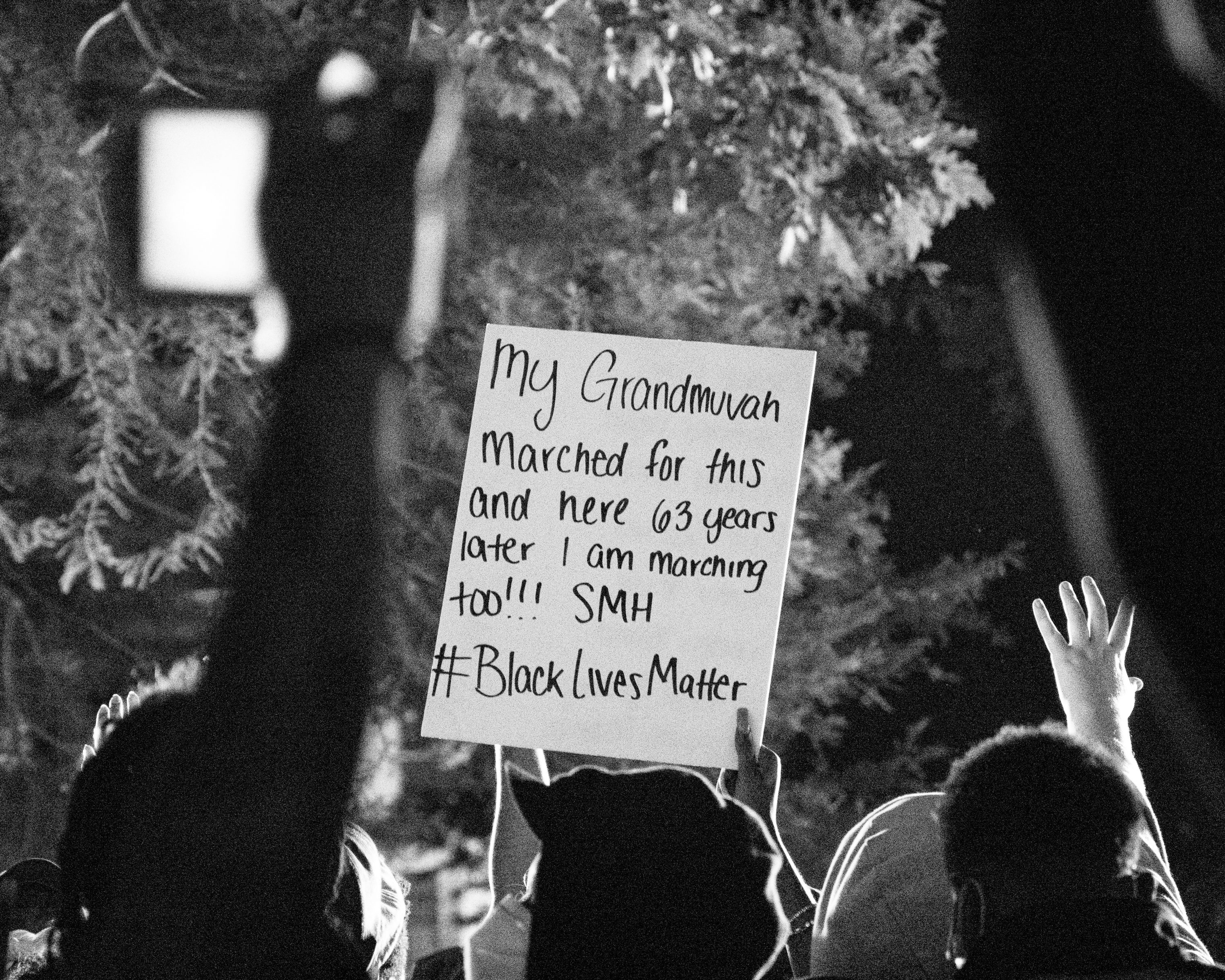

– This stock photo shows a protestor’s sign that reads, “”My grandmuvah marched for and 63 years later I am marching too!!! SMH #BlackLivesMatter”

Building Humility and Empathy had been an ongoing part of our antiracist work from the beginning. Much of the work we had done prior to ECCD focused on moving from sympathy to empathy and on building an understanding of racism as systemic. Recognizing that being a nonracist doesn’t make you an antiracist requires a reexamination of our personal histories. ECCD offered a needed framework for deepening and renewing this engagement.

This work relies heavily on the ability to lean into discomfort, an action that takes effort since we instinctively avoid discomfort. It entails the kind of rhetorical and active listening that Writing Studies folks are familiar with through the work of Krista Ratcliff (2005) and others. As the Field Guide acknowledges, it requires (and builds) self-awareness and reflection. The work we did in professional development with reading, annotating, reflecting, writing, and talking/listening to each other had given us tools. Yet, it is still hard work that takes time and most importantly, trust.

ECCD introduces this work with guidance for engaging. In addition to leaning into discomfort, there is a focus on the kind of listening that suspends judgement and allows the listener to identify their own biases as they come up. Peer Reader, Sarah Drepaul, highlights what the work of radical listening has been like in the process of ECCD:

I live in a predominantly black and brown immigrant neighborhood on the edge of Queens, NY. The planes fly the lowest over these houses, the streets lift up with the smell of goat curry and people cut their meat on concrete backyards and curse in Creolese. I navigate these sounds inside of me when the new ones build up: the white students at Drexel University, something called yacht rock coming from the back, and hearing myself be called “articulate.”

What did “articulate” Sarah have?

Where does “articulate” Sarah hide the rest?

I didn’t talk about racism in my family. I hardly did at school either–but I did feel proud of my diverse group of girlfriends, and I did feel safe walking home with faces that looked like mine and sounded like my parent’s homeland. If we weren’t speaking about racism, we were feeling its absence–and oftentimes presence. Racism was localized; a lot of it was internalized. I did not know how to verbalize it beyond my embodied experience of it. The Writing Center’s approach of radical listening and unlearning gave me the tools to shift words as passive receptors to something I could rebuild and use for myself.

When I took Peer-Reader-In-Context, one of the requirements to work at the Drexel Writing Center, I was forced to grapple with the words I was and was not using when addressing racism: the difference between systemic and systematic, the implications of a standardized language, the code switching that takes place in my household but I wouldn’t dare mention in a class full of white people. What sacrifices was I making for the comfort of the education system–for the comfort of my white peers?

In the Writing Center, our relentless practice of annotating anti-racist texts taught me that the unlearning, even as a BIPOC, begins with me. No person of color’s experience is a monolith and leaning into that is uncomfortable, especially when you are a student in a predominantly white institution who is trying their hardest to blend in (read: trying their hardest to prove that they belong here just like everyone else). But with self-annotations, I challenged the Western academic ethos of: “being a good reader means asking questions.” Who is allowed to raise questions in a classroom setting where the set reading, and the language of that reading, has been standardized and determined by an education system that is not inclusive of knowledge that questions its own history and language?

The Writing Center’s historic and healing approach gave me the space and tools to question not only the academic readings I was given, but to question my own questions. My implicit biases, the ones that inform my reality, were no longer static because of my active voice; because I was no longer navigating this society with just my personal history and understanding.

It’s still hard and I have no obligation to sit down and crack open the books for every white person I know, but I do have an obligation to myself, my history with language, to not sit silent in the comfort created by white supremacy. My sacrifices with words were transformed in the Writing Center because of the inner work of reteaching myself what I have to say is important and is ALSO worth challenging. It is worth re-examination as much as it is worth reconciliation–and that is the mark of a “good reader” with their “good questions.”

Despite the imperfections of our work with ECCD, it was beginning to shift mindsets. Peer Readers started to move from envisioning themselves as activists fighting the boogieman of systemic racism out there—in the university, in their communities, in the country—to staying in the present moment with themselves at the center of the scene. Their mindsets began to shift toward the actions of listening and receiving, of seeing themselves as interconnected, and of understanding that there is much they do not see about themselves and others.

Empathy has grown in a number of ways in this process. Peer Reader, Aaliyah Sesay, explores the different ways we show up in this work and the importance of attending to the act of listening to each other’s experiences and perceptions:

At the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association Conference, where my peers and I presented on language equity, we attended a panel of students from an HBCU who talked about the work they do at their writing center. At some point, tension arose between the panelists and the audience. One of the tutors spoke personally and mentioned that he believed standard English stood as a point where people could understand one another. Members of the audience questioned whether the panelists had a full comprehension of standard English’s racist inception and how it still acts as a way to uphold the institutional racism. I felt myself getting hot, because I sympathized with the student. They were black students in a white space being told how racism works. Although I understood where members of the audience were coming from, I didn’t think they could see the same for the panelists.

It is moments like these in which we have to pause. Black people exist in a body that is marked as “black,” accompanied by so many connotations and preconceptions. Even for those who are aware of their prejudices and learned biases, there is a level of self-checking that they will always encounter. Of course, I don’t believe that everyone thinks of me in such a way, but there are so many elements of blackness that I choose to avoid in order to be acknowledged outside of what non-black individuals consider “blackness.” From how I do my hair to what I wear, my outward appearance has to subdue my blackness, not amplify it, in order for me to be seen as a certain black woman and not another. Then once I’ve been given the benefit of the doubt, how I speak has to demonstrate that the chance they’ve given me to speak is worthwhile. “Y’all” and “sis” don’t dare leave my mouth; my voice is no longer in its comfortable bass but a higher register to mimic what I’ve been told is femininity. And this we know is racism, the kind the audience members were touching on. We do a disservice, though, when we ignore history and its effects that we’re witnessing in real time.

Literacy and language in black American history cuts deep. People were pulled from their homes, forbidden from speaking native languages, and were unable to learn the language of the masters. This history lingers and heavily weighs on black folks today. We understand that language is power. It’s difficult when the society around you considers the words from your mouth an invalid form of communication. I agree that this is thinking we must correct and a system we must redesign, but we can’t lash out at victims. The student panelists and I are all victims of theft and denigration of our language. We can’t help but fall into practices of standard language ideology because we see the privilege of being in these spaces and don’t want to keep it from others.

History and Healing

Many of the challenges we face in Building Humility and Empathy were intentional designs of inequitable systems. When systems produce vastly different outcomes under the guise of national myths like individualism, freedom, and equality (but not equity), we live with a restricted view of our own histories, a limited understanding of how we got to where we are and what it took to get here. Victor Villanueva dissected the tropes that hide racism in our national narratives and myths, the stories we tell ourselves that create ideologies and worldviews, urging writing center practitioners to attend to the silence that omits race and the reality of racism (2006, p.11).

Voices in writing center studies have increasingly drawn attention to issues of race and equity in the recent past (Condon, 2007, Condon, Green, and Faison, 2020, Denny, 2010, Faison and Trevino, 2019, Garcia, 2017, Geller et. al., 2007, Green, 2018, Greenfield and Rowan, 2011, Grimm, 1999, Lockett, 2019, Young, 2010, etc.). Scholars like Aja Martinez bring fresh genres like critical race theory counterstory, through which Writing Studies can listen to the living experts—faculty, staff, and students of color—to disrupt and dismantle master narratives, so that “voices from the margins become the voices of authority” (2014, p.1). Engaging with this scholarship helps students to situate the work of designing equitable writing centers and programs in new practices that would interrupt historical patterns and move towards healing. But History and Healing contain many dimensions and require work beyond the scholarly texts of writing studies.

ECCD’s Field Guide offers an exercise that should work to highlight the gap between official narratives of events and lived experiences of them. It should highlight how events disproportionately impact members of a community and the power we have to shape history. It did not quite work in way that for us.

Peer Readers chose to talk about events, from the trivial to the pivotal, but were unable to conceive of a narrative that included them in any real way. They identified that design of systems was a factor of inequitable outcomes, but could not see how that functioned. This became an exercise in distancing themselves from the impacts of history. They resisted seeing themselves as part of history.

I refocused our conversation on the particular history of the DWC. Through oral history, we examined the inception of the writing center and its many evolutions. As I explained the way the writing center was designed in its various iterations, I asked them to listen for where power was invested and what outcomes the writing center was designed to produce.

The realizations that happened during this process were key to understanding the power that they had in their work with students. Once they could see the earlier designs of the writing center—as a tool to police student language (and, therefore, identities) to fit the white racial norm of language in the academy, where peer tutors functioned as little more than enforcers of systems that reduce idiolects to a standard variety, where there was little investment in peer tutors themselves or in their relationships with other students—they were able to examine the present-day writing center and their roles as peer tutors more fully. They were able to see their own power to design our program for different outcomes. They began to understand their own agency.

We continued to engage with our institution’s history and our roles in that history. I asked Peer Readers to consider how Drexel designs recruitment and how they became Drexel students. While the university’s recruitment system felt opaque to them, they also had difficulty identifying systemic structures that had led to them to Drexel. When they struggled with applying their knowledge of systemic racism to their own lives, I looked to a resource from another nonprofit organization, Grassroots Policy Project, an organization that does antiracist work in connecting policy analysts with organizers. One of the resources they make available to organizations seeking to create structural change for equity is the Race, Power, Policy: Dismantling Structural Racism workbook. It offers the, “Step Forward, Step Back,” workshop to illustrate the effects (or outcomes) of structural racism (a design).

As Peer Readers participated in this exercise—moving forward and backward, physically demonstrating how they’ve each benefitted or suffered from systemic racism—they looked around themselves and saw how they are implicated and enmeshed in systemic racism. It became clear that some students were never allowed to forget the realities of our systems while others had never been aware of the structures that elevate them. In the conversation that ensued—about red-lining, voting rights, persistent school segregation–some Peer Readers wondered if they had truly earned their place as a Drexel student or if it was simply the designed outcome of an unfair system. They asked themselves if it was even possible for both to be true.

After working with our personal and institutional histories, we shifted our focus to a reckoning with our national history. It felt like a gift that The 1619 Project was published in this time period. We integrated it into our professional development in the Fall 2019 and Winter 2020 terms, reading and annotating it a little bit at a time. Our professional development structure includes reading, annotating, reflective writing, and small group conversations in which we listen to each other’s thoughts and integrate them into our own. The 1619 Project proved to be an important tool for using that structure to engage in History and Healing at the larger level of our nation’s history and the ways in which the past is present.

These excerpts from the reflective writing students produced in conversation with the 1619 project show History and Healing in progress:

All country music stems from blues and bluegrass music which started with slaves, even the banjo comes from an African instrument brought to the US by slaves. Black people were some of the first farmers, cowboys, and working people, and country music is created for farmers, cowboys, and working class people. Yet, Lil Nas X is left off of country radio and many people boycotted the CMA awards for even letting him perform, calling it “cultural appropriation.”

– Mary Allain, Peer Reader

“That would be bad, but it’s statistically very unlikely” (68). I noted here that I can’t imagine having to comfort myself with statistics, when even the statistics are turned against me. Black women being 12 times more likely to die in childbirth, in one of the biggest cities in the world, is yet another reinforcement that even on a physical level, the black population in the United States continues to be underserved and misunderstood Why are so many more black women dying in childbirth when we are living in a country where our medicine used to be the best in the world? Where we have infinite technologies and information at our fingertips? Why aren’t we doing better?

– Kelsey Hendry, Peer Reader

“A plantation at the end of the 20th century…” tell it how it is. I simultaneously love and hate that this metaphor is so on the nose that it’s essentially not a metaphor. This prison is the plantation. On a critical level, they are essentially the same, deviant only in their placement in time.

– Janae Kindt, Peer Reader

What I found myself stuck on and struggling with was the idea of white rage at Black excellence, and the way the Reconstruction was torn down because of the threat to White Supremacy, and how all of that echoed what we saw in 2016, with the White Supremacist backlash to Obama’s presidency. The idea that Elmore Bolling was thriving and helping other black folk to thrive, and THAT was the sole reason why some thought he deserved to be murdered– that the prosperous black neighborhood in Tulsa, OK was ravaged by white rage, leaving 300 black people dead and 10,000 left homeless– these two stories that stand in for so many more captured my imagination and made me think about why reparations for many Black Americans ought to be at the forefront of the U.S. economic policies in the foreseeable future.

– Devin Welsh, Peer Reader

As a tour guide in the “Birthplace of the American Revolution” it was exhilarating and deeply unsettling to look at how I have been told to run my tours as we roll through the Historic District… There are so many lies by omission built into the “history” of Old City… and it is the reality that I get to choose what to and what not to omit that fuels my exhilaration in exploring these topics through the 1619 Project.

– Vikki Klein, Peer Reader

“…one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.”

Excuse me, what?

A level of confusion, anger, and surprise. I was definitely taken aback. I think I believed in this country more than I was expected to…This country that my parents fought so hard to get to, their “Promised Land”, obstinately refuses to acknowledge their humanity. It’s a lot to take in.

– Aaliyah Sesay, Peer Reader

The concept of a civic vision that is rooted in racism, in the name of peace and progress, make me think of the definition of these words, in a visual way. Does the civic vision mean adhering to racial segregation because this is normalized, and to continue as such is to execute something so fundamental in our history, that panders to whiteness? Why is the real vision, of breaking down those racial barriers, the opposite of a “peace”?

– Sarah Drepaul, Peer Reader

We cannot change what we cannot see. This ongoing work in History and Healing is painful and even traumatic, but it continually reveals systemic designs of our past and present, a necessary step in moving toward Acknowledging and Dismantling Power Constructs.

Video 1 – Peer Reader antiracist training with Peer Reader, Sarah Drepaul, providing voice over. This is a video of Peer Readers engaged in working with the Equity-Centered Design Field Guide with a voice over of Sarah Drepaul detailing how ECCD helped her delve into her own history with her home dialect and her process of healing her relationship with language and identity.

Acknowledging and Dismantling Power Constructs

Ongoing work in History and Healing facilitates uncovering power constructs and acknowledging the power in the decisions we make. As much work as we had done, we were only at the beginning.

This stage of ECCD begins with an exercise that engages participants in engaging with, “all of the ways you interact with power” (FG:ECCD, 2018, P.29). Participants drew images that illustrated the ways the hold power, experience power, and are acted upon by the power others hold over them.

The exercise engages participants in answering questions about forms of power that help and harm them, power they are given, and how their relationships to power impact their work.

The answers were useful, but incomplete. There was a tendency to move too quickly past acknowledging power constructs and toward dismantling them. Facilitating self-work alongside communal work was necessary for deeper engagement in this part of the ECCD process, as Peer Reader Devin Welsh describes:

Where to start when it comes to anti-racism? Well, for Diab, Ferrel, Godbee, and Simpkins in their 2013 “Making Commitments to Racial Justice Actionable,” it starts with the self:

Dialectic thinking directs our attention toward the important role of self-work – or an individual’s own ‘self-study,’ with the goal of building self-reflexivity – and plays alongside and in the service of work outward in the world and with others. This self-work entails an investment in a serious, processual self-reflection and a rich dialogue with the self about how we think, how we feel, and finally how we invent time and space as lacking or available. (Diab, et al. 2013, pp. 7-8).

Beginning with the self is both incredibly important and daunting, especially if you don’t know what to read, or more importantly how to read it, or have the space or support to reflect on what you’ve read. Fortunately, Drexel’s Writing Center is built around this idea of dialectic thinking. We are given not only readings that allow us to do this self-reflective work, but also the time, space, and support that fosters reflection.

We are trained to read with a pen in hand, annotating the text in front of us, scrawling in the margins whatever in the text makes us think, or question, or feel. From these annotations, we go back and interrogate what we were thinking, what stood out to us, and how that connects to our positionality or worldview. We also have the support of what we call a Teaching Circle, where we aren’t doing this this work alone, but together. These groups where we discuss what we noticed and reflected on allow us to engage in that “dialectic thinking” highlighted by Diab et al. These groups, and our Center, are incredibly diverse and each Peer Reader brings a different perspective to the table.

These acts of reading, annotating, reflecting, and discussing is what allowed me, as a naïve sophomore, to begin to rethink my position in the world and how I see the world. Vershawn Ashanti Young’s “‘Nah, We Straight’: An Argument Against Code Switching,” was one of first pieces that really chafed against my worldview (2009). I went through school as a tan boy with a Black dad and a White mom, hyperaware of how I was perceived. I thought that a mastery of Standard Academic English (SAE) would legitimize my intelligence and help me professionally. Code switching is a common fact of life for many/most people of color and I had accepted it, uncritically, as common sense. Reading Young’s piece challenged my need to cling to SAE and signaled where I had work to do.

This text unearthed my lack of understanding of how systemic racism operates, let alone what I can do about it as a Peer Reader in an institution of higher learning. By analyzing my annotations and my push-back on the text, I began to see how I perpetuate and participate in these toxic ideologies, and I also was able to understand why. That critical self-work had to happen before I could make an authentic and actionable commitment to anti-racist work. Engaging with Young’s piece and others like it in this way – through not only active reading, but tracing and reflecting on our thoughts so that we can take that next step and explore them in a dialectic manner with our peers – is pivotal in the work of “acknowledging and dismantling power structures,” one of the key pieces of the framework of Equity-Centered Community Design.

Our conversations shifted to the need to work with and not for the Drexel community as this stage of ECCD emphasizes. We didn’t want to make assumptions about the larger student body and the writers we work with, or the faculty and staff we hoped to work with in the future.

We returned our energy to Inviting Diverse Co-Creators. We reached out to students who indicated in our survey that they wanted to engage with us in ECCD. We began to plan workshops, a blog, and a podcast to bring the wider community into this work. There was a satisfaction in transferring our energy to something that felt active and like forward movement.

Part of moving forward included outreach to DWC alumni. Four Peer Readers conducted research on how alumni are taking their training in antiracist pedagogy into the workplace. They presented on their findings at the Mid-Atlantic Writing Centers Association Conference at Towson University in March, 2020, shortly before the pandemic induced widespread stay-at-home orders.

In reflecting on that experience, one of the Peer Reader presenters, Mary Allain, uses narrative in the way that Diab et. al. describe, as a way into the deeper work with self, community, and institution:

To understand the impact ECCD has had on me you would need to understand who I was when I first joined the writing center. I grew up in a small, rural town. My high school was majority white, complete with a Native American mascot and a history of running teachers of color out of town. I knew racism still existed, I saw the textbook definition still exist in my school, and I knew that I cared about getting rid of it. But I didn’t have the tools to understand that I thrived in it. Because my beliefs were in the minority in my community, I developed this antagonizing, defensive, “us vs. them” view of racism. It was something that was outside of me, a group of individuals that I needed to fight and change because I knew better than them somehow. Removing racism from myself wasn’t just a way to feel like I had control over something that I knew was wrong (without really trying to understand it), but also something that I was praised for. I organized countless service events for communities I never understood but claimed I could help, and I was rewarded for it. I thought that if I could be the one to get rid of “The Racists”, then I could save the world and get patted on the back at the same time.

Once I started working at the writing center, I felt like I was radicalizing. Every week we read and responded to articles that changed who I was as a person because they exposed perspectives that had been given to me through the white gaze and experiences that intersected in ways I could have never imagined. They made me very self-conscious of the ways that I inevitably made my care and activism about myself or about what I assumed others needed.

But the process that I went through at the writing center broke me down, exposed shadows that I overlooked in my past, but still welcomed me back to the conversation. I went through periods of shame spirals where I felt like my voice meant nothing, but I had a community that would always eagerly ask me to share. This process of being given information, a space to react, and then a group of diverse people to widen my very narrow perspective was the most important experience I’ve had, and I never knew I needed it.

I got so frustrated with how unmovable the world seems to be. I was really just searching for a way to go back in time, to a world where the overwhelming amount of whiteness lifted my guilt and told me that it’s not my fault. But there was no going back. The community at the writing center wouldn’t let me. I was left with this feeling in the back of my throat that I was powerless.

As I approached graduation, I wanted to stop feeling so helpless and exhausted in thinking about the design and redesign of racist structures. My peers and I started researching how alumni have continued the work that they experienced in the writing center. We talked with alumni about where they are now and the tools they have taken with them. The conversations between alumni and us researchers were extremely important to me in understanding ECCD as more than just a way to make a more equitable center but also to make seemingly unmovable institutions more equitable.

[Alumni] had amazing experiences of being hesitant at first, and then graduating with tools to analyze the systems they interact with. What became an interesting part of the research was that all of them still feel exactly the way I do: that their industries are unmovable and they’re simply entry level employees. But once we started talking in detail, they shared the ways that they talk about this with their coworkers and use their understanding of code meshing with customers. Many alumni began working in school systems where they interacted with students every day in equitable ways.

As much as these small changes feel like moments that are no match for harmful structures, it exposed how easily I overlook them. I’ve always loved the romantic idea of protests, walk-outs and boycotts without internalizing the understanding that these are equal to the quieter versions of social change. Again, I was looking at ECCD through the experience of being very new to the idea of how slow and small actual change is, and the compromises that come with it. But at least this time I was aware of it and had the tools to confront it. I could finally start understanding change as bits of empathy and humility intentionally woven into every action you take.

This is the work. It’s developing and ongoing. In the aftermath of the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breona Taylor, and George Floyd, this work can feel small and insignificant. Insufficient. But as we sit in our homes, scattered across the globe, we are still coming together in this work, as the structures of systemic racism are laid bare by Covid-19 and the civil unrest gripping the nation in response to the silence and inaction of our leaders, in response to a country bent on the continual construction and enforcement of a racial hierarchy.

We know we cannot dismantle what we cannot acknowledge. As I interviewed my co-authors to aid in drafting this piece, the amount of work ahead of us surfaced in each conversation. We had not really confronted microaggressions happening in our own community. We had not sat long enough with disparities in power that exist amongst us to fully understand their presence in our relationships and work together.

This summer, we’ll continue with ECCD, questioning again with each other where we have power, how we can share it, and how to give it up. Even as we move forward in Inviting Diverse Co Creators at the institutional level and into the next stages of ECCD, we will redouble our efforts at self-work and work with our small, writing center community to lean into what has been uncomfortable—risking the relationships we value with each other in order for them to be deeper, more real, and for our work together to have a chance at redesigning for equity.

The desire for forward progress is always present, rooted in how intractable systemic racism feels. But the reality of this work is that it is circuitous and chaotic, exhausting and renewing, painful and revelatory. We believe the present moment offers unique possibilities for engaging in this work more broadly in our national policies and institutional practices and that the use of tools like Equity-Centered Community Design can make redesigning for equity scalable across writing centers and programs, universities and businesses, communities of all kinds.

References

Coates, T. (2015). Between the world and me (First ed.). New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Condon, F. (2007). Beyond the known: Writing centers and the work of anti-racism. The Writing Center Journal, 27(2), 19-38.

Condon, F., Green, N., & Faison, W. (2020). Writing Center Research and Critical Race Theory. In Theories and Methods of Writing Center Studies (1st ed., pp. 30–39). Routledge.

Denny, H. (2010). Facing the center: Towards an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Diab, R., Ferrel, T., Godbee, B., & Simpkins, N. (2013). Making Commitments to Racial Justice Actionable. Across the Disciplines.

Faison, W. & Treviño, A. K. (W.). (2020). Race, Retention, Language, and Literacy: The Hidden Curriculum of the Writing Center. In Learning from the Lived Experiences of Graduate Student Writers (p. 92–107). Utah State University Press.

García, Romeo. (2017). Unmaking Gringo-Centers. The Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 29–60.

Geller, A. E. (2007;2006;2013;). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Green, N. (2018). Moving beyond alright: And the emotional toll of this, my life matters too, in the writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15-34.

Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (2011). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Grimm, N. M. (1999). Good intentions: Writing center work for postmodern times. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook-Heinemann.

Horton, M., w/ Kohl, H., & Kohl, J. (1997). The long haul: An autobiography. New York: Teachers College Press.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I Call it the Academic Ghetto: A Critical Examination of Race, Place, and Writing Centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2).

Martinez, A. Y. (2014). A plea for critical race theory counterstory: Stock story versus counterstory dialogues concerning Alejandra’s “fit” in the academy. Composition Studies, 42(2), 33-55.

Mathieu, P. (2005). Tactics of hope: The public turn in English composition. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Ratcliffe, K. (2005). Rhetorical listening: Identification, gender, whiteness. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

“The 1619 Project.” (2019). The New York Times. np. Print.

Villanueva, V. (2006). Blind: Talking about the new racism. The Writing Center Journal, 26(1), 3- 19.

Young, V. A. (2009). “Nah, We Straight”: An argument against code switching. Journal of Advanced Composition, 29(1/2), 49- 76.

Young, V. A. (2010). Should Writers use they own english? Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(1), 110-117.

Appendix A – Equity-Centered Community Design Field Guide Community Agreements (ECCD, 2018, p.8)

- Ensure all voices are heard.

- Actively listen and respect differences in opinions.

- Use “I” statements. Remember, you cannot speak for others, only your own experiences and opinions.

- Lean into discomfort.

- Address the issue, not the person. If conflict arise, we should not personally attack someone.

- Be honest and embrace honesty.

- Don’t assume everyone has the same beliefs and understandings as yourself. • Don’t disclose others’ information without their knowledge and consent.

Appendix B – Things to Remember (FG:ECCD, 2018, p.9)

- People are not born with prejudice. Prejudice and bias are learned through experience. • We are all members of many social identity groups, based on race, gender, ethnicity, class, age, ability, sexual orientation, religion and others.

- People are not defined by one identity, but a myriad of identities and characteristics. Everyone is intersectional. However, the ability to define oneself’s primary identity or preferred lack of, is up to that person and not others.

- Oppression takes many forms, including prejudice, discrimination, marginalization, powerlessness, exploitation, violence, and cultural imperialism.

- There is no hierarchy of oppression. Oppression is oppression. Underrepresented and marginalized groups should not compete for the “most heavily oppressed prize.”

Appendix C – Sarah Drepaul Video 1 Voice Over Transcript

Sarah Drepaul, Peer Reader: Fade in: … but like my understanding of that is so nuanced. Now, I’m like, it’s not like the standardized, like, commonality part of writing that, like, I learned like, before college and like, in college.

Like that’s very like, geared towards a certain type of person. Um, and realizing that it was designed that way, made me feel less like I have to be squeezing into this thing.

Um, so… it became less passive because like it…with all of these tools like from the Writing Center, I was like, okay, like I could see myself in writing.

And seeing myself more in writing, but also like helping me write my own words that were like actually reflective of like my upbringing and like my identity.

And like it’s not this exercise of, um, it’s not like an imitation game and like I don’t want it to be either so, it’s just like this urge to call that out when I can.

Because I don’t know. I think that’s, like, for me, like that’s like where the true power of like writing is and it’s not this, like, great equalizer.

Um, especially not like the standard English like format.

And I think that just goes back to knowing that like this is what this was designed for and like this is how we can redesign that or like deconstruct this thing.

Um, it makes me feel more seen and…

Also, it gave me better understanding of like the dialects, like in my own house or like the dialect, like with my friends of color.

It kinda gave it like an actual place, um…whereas before, I felt like I was always trying to create that. And I think that’s like the whole thing with like self-identification like once I had that vocabulary.

Like the whole stuff with like code switching and all of that. I was like, this is a real thing. Um, so it was helpful and like empowering in that way.