Stephanie Aguilar-Smith, University of North Texas

Floyd Pouncil, Michigan State University

Nick Sanders, Michigan State University

Abstract

This article describes our writing center’s professional development curriculum for our more than 100-person staff, geared toward disrupting linguistic oppression. In developing and rolling out our recently codified language statement, we join a long line of research advocating for language justice across academe and, in particular, within writing centers and writing classrooms. After situating language justice as a historical issue, we outline the curricular arc of our center’s professional development designed around understanding and, ultimately, advancing language justice through our staff’s roles as writing consultants and as instructors and students themselves. Specifically, for our staff to better understand the socio-cultural functions of language and its material consequences, our curriculum foregrounded how white supremacy shapes standard language ideology—the ways individuals are socialized to value white normative language practices and devalue all others. We end by offering reflections based on our experience designing and facilitating our center’s professional development curriculum and mapping future routes for language justice for our center, which we encourage other writing center practitioners to translate and apply to their respective roles and institutional contexts.

Keywords: staff education, professional development, linguistic justice, language subordination, linguistic racism, social justice

Stories from The Center

During a recent consultation, Jamie, a Ph.D. student and seasoned writing center consultant, worked with Li Fang, a graduate student in political science. Li explained that, as an English Language Learner, he finds it challenging to fully express his ideas in English and is overwhelmed trying to edit his dissertation proposal in light of his advisor’s feedback. Looking through some of the input, Jamie realized that many of the suggestions were about missing or “misused” articles, verb tense, etc.—minor issues that did not seem to cause any significant misunderstanding. Although Li’s advisor offered a few substantive remarks about ways Li could strengthen the paper, Jamie left the session ruminating on how people can “accept” those who speak with an accent but are often rather unforgiving of those who write with one.

Spencer, a relatively new hourly writing center consultant, recently met with Alex, an undergraduate student who uses they/them/their pronouns. Per the instructions, Alex wrote their essay in first person and effectively addressed all parts of the assignment, earning an A. Given the high grade, Spencer was somewhat surprised Alex scheduled an appointment to discuss the paper until Alex showed her some of their instructor’s feedback. Alex’s instructor had flagged, multiple times, Alex’s use of their/them, suggesting these were “errors,” and Alex was concerned about how to approach upcoming work in the class given this feedback.

Li and Alex’s experiences and similar ones are commonplace in writing centers. Writers whose social identities and language choices unsettle normalized—legitimized—academic conventions undergo linguistic violence from standard approaches of language policing (Baker-Bell, 2019; Faison & Treviño, 2016; Green, 2018; Lockett, 2019). Greenfield (2011) explains that typical writing center pedagogies overtly and covertly engage racist assumptions about students and their language, coding who belongs (e.g., middle/upper-class white students) and who does not (e.g., minoritized students). In other words, standard language pedagogies are positioned as gateways to social mobility, particularly for students of color. However, in reinscribing these standard approaches, writing centers act as gatekeepers, reifying an already unjust social system. Given these legacies, writing centers must reckon with the higher education system’s perpetuation of linguistic oppression.

Our writing center at Michigan State University (The Center, henceforth) works toward language justice by fashioning consultants into critical interventionists who can grapple with the complexities of language alongside writers. The Center’s rollout of its language statement in the spring of 2018 demonstrates the codification of this charge to enact language justice in policy and practice. However, since consultants are embedded within the very institutional environments that our center and others work to disrupt (e.g., those at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, American University, and East Carolina University), writing center administrators must (re)develop ideological frameworks alongside their staff. As Grimm (2011) writes, “If we want to avoid complicity with racism and other forms of exclusion, then those tacit theories about language, literacy, and learning need to be made explicit and open to revision” (p. 78). Thus, considering Grimm’s words, as a center, we recognized the need to address what had become institutional and, consequently, subconscious. Ultimately, we worked toward unsettling institutionalized linguistic oppression by implementing a professional development curriculum that reckoned with our staff’s previous and ongoing socialization.

As the title suggests, in this article, we present an opportunity (i.e., staff professional development) to forge a better writing center—one that advances language justice. Specifically, we first discuss the enduring charge for language justice in writing and writing center studies. We then put this history in conversation with our present-day writing center context. Given the history of language justice in academia alongside our center’s institutional position, we then articulate The Center’s year-long staff professional development curriculum designed to (a) unearth language-related assumptions, (b) interrogate the relationship between language and power, and (c) workshop how to enact The Center’s values around language justice practically. Finally, we reflect on how consciousness-raising is but one component of realizing the commitments made in The Center’s language statement and discuss possibilities for advancing language justice within and beyond our center—possibilities which we encourage other writing center practitioners to translate and apply to their respective roles and institutional contexts. Ultimately, by sharing our insights on staff education around language justice and, in particular, offering specific examples of activities and prompts within our professional development curriculum, we hope to equip other writing center scholars and practitioners to join us in this ever-important effort.

The Charge for Language Justice

As the opening vignettes illustrate, instances of language subordination abound across higher education, even on college campuses that purportedly value diversity, equity, and inclusion. And yet, the charge for language justice and the explicit recognition of white supremacy’s embeddedness within language date back more than 50 years (see, e.g., Labov, 1975; Sledd, 1969). A leading scholar-activist for African American children’s education and the legitimacy of Black language, Geneva Smitherman has detailed the rich, albeit fraught, history for language justice. Specifically, she explained that early on, many scholars considered it “purely academic to demonstrate, in Emersonian, armchair philosophizing style, the legitimacy of the oppressed language and culture without concomitantly struggling for institutional legitimacy in the educational and public domains” (Smitherman, 1995, p. 21). In the late 1960s though, such professing transformed into action, with a cadre of scholars working to “legitim[iz]e the culture, history, and language of those on the margins” (Smitherman, 1995, p. 21). And in the fall of 1974, the Conference on College Composition and Communication released its canonical resolution, Students’ Right to Their Own Language, stating:

We affirm the students’ right to their own patterns and varieties of language —the dialects of their nurture or whatever dialects in which they find their own identity and style. Language scholars long ago denied that the myth of a standard American dialect has any validity. The claim that any one dialect is unacceptable amounts to an attempt of one social group to exert its dominance over another. Such a claim leads to false advice for speakers and writers and immoral advice for humans. A nation proud of its diverse heritage and its cultural and racial variety will preserve its heritage of dialects. We affirm strongly that teachers must have the experiences and training that will enable them to respect diversity and uphold the right of students to their own language. (Conference on College Composition and Communication, 1974, pp. 2–3)

The precedent set by this resolution (a) engendered intense critique (see, e.g., Colquit, 1976; Smith, 1976); (b) spurred substantive political and legal discussion, including proposals for national language policies (see, e.g., Freeman, 1975; Reising, 1997); (c) and extensive scholarship on language inclusion and language justice, particularly work on how to discuss and enact these values (see, e.g., Judy, 1978; Brannon & Knoblauch, 1982; Delpit, 1988; Kinloch, 2005; Parks, 2000; Scott et al., 2009; Williams, 2013).

In developing this professional development program, we built on a long history of language justice in writing studies and English education. As such, we are not the first to call for this kind of shift in writing center discourse. Two decades ago, Grimm (1999) challenged commonplace writing center pedagogies, like Brooks’s (1991) non-directive tutoring approach and North’s (1984) “better writers, not writing” axiom. Instead, Grimm embraced postmodern ways of doing writing center work, which respond to Boquet’s (1999) claim that “writing centers remain one of the most powerful mechanisms whereby institutions can mark the bodies of students as foreign, alien to themselves” (p. 465). This writing center scholarship suggests that writing centers have a moral imperative to serve as critical interventions that redress harmful ideologies from their institutional positions. We also drew on more recent scholarship from writing center scholars (see, e.g., Faison, 2014; Greenfield, 2019; Greenfield & Rowan, 2011; Inoue, 2016; Young, 2009) and language and literacy scholars (see, e.g., Baker-Bell, 2020; Lippi-Green, 2011; Rosa & Flores, 2017) committed to language justice. Collectively, this line of scholarship pushes educators to see the cultural work of languaging within the broader socio-historical and socio-political context of white supremacy. For instance, Rosa (2019) discusses the linguistic and racial co-naturalization process and how it normalizes particular languaging practices and makes deviant others, thus reinscribing colonialism, racial capitalism, and neoliberalism. In a writing center context, Rosa’s analysis of the racialization(s) of language compels practitioners to unearth unconscious prejudice by interrogating language standardization as a colonial project. Accordingly, we argue that writing centers, including ours, must understand the historical, social, and cultural contexts in which language and race intertwine. Among such work, we primarily centered Lippi-Green’s (2011) conceptualization of standard language ideology—the covert socialization of particular values and expectations related to language and the effects of such judgment. Informed by her work, we named how linguistic oppression, including linguistic racism, operates through a range of social institutions, especially the system of U.S. higher education.

In sum, this rich body of scholarship helped us name language as a complex cultural process, a way of being in the world, and a way of signaling community allegiances. Accordingly, this literature prepared us for the hard work of aiding our staff in unearthing their conscious and unconscious involvement in perpetuating standard language ideologies and linguistic oppression. Even more, in foregrounding the perverse effects of socialization, namely of standard language ideology, this scholarship guided our efforts to advance language justice specifically through targeted professional development programming for our staff.

Institutional Context and Our Charge

Embodying a queer-feminist ethos, The Center operates with an “expansive view of writing, literacy, and pedagogy” (The Center, n.d.b, para. 1) and values collaboration, multimodality, interdisciplinarity, and diversity. This vision allows us “to meet the ever-changing needs of a diverse constituency and challenges us to continually grow” (The Center, n.d.b, para. 10). Part of a large, research-intensive university, The Center has a large disciplinarily diverse staff of undergraduate and graduate consultants, representing a range of fields, such as writing and rhetoric, history, teacher education, English, music, and political science, among others. In addition to graduate assistants, The Center employs upwards of 75 hourly consultants, who work anywhere from 3–20 hours a week, making our staff mostly contingent and subject to high rates of attrition from year to year. As Stock (1997) explained about the founding of The Center, we must “recogniz[e] the university as a community of learners—student and faculty learners who are themselves human beings with histories and hopes, with projects and prospects, with relationships and responsibilities” (p. 10). This approach has always meant continually listening to consultants, clients, faculty, and staff, and the writing center/academic communities with whom we intersect. Again, as Stock explained, from the opening of The Center, “we [have] made our work the object of our inquiry in order to improve and refine it on a continuing basis and in order to contribute to the development of knowledge about literacy and learning and their interrelationships” (1997, p. 17).

In the spirit of this mission, we published our language statement. In the vein of Students’ Right to Their Own Language, our language statement “challenge[s] the notion of standard English as the only correct expressive form” (The Center, n.d.a, para. 1) and “affirm[s] and support[s] writers’ choices of languages, pronouns, English(es), stories, and perspectives” (The Center, n.d.a, para. 6). Considering linguistic oppression within our institution, we worked to re-orient consultants and have them critically investigate how white supremacy shapes individual values around language and, further, how it inflicts harm on minoritized writers. In doing so, The Center’s staff professional development curriculum worked to unearth what language is, does, how people come to know it, and its material consequences. Specifically, through paid, bi-monthly 1.5-hour staff meetings, which consultants are expected to attend, our consultants began uncovering hidden assumptions around language to better enact necessary perspectives that are responsive to students and their linguistic identities. The practice of calling in our philosophies, procedures, and programming led us to the language statement and continues to lead us in (re)developing and reflecting on it—an ongoing process we share here through story, theory, and reflection.

Enacting Language Justice Through Professional Development

The ongoing training we designed was scaffolded within a broader set of inward and outward-facing experiences around language, including a sponsored speaker series investigating the intersections among language, race, gender, region, class, nationality, and queerness. Across these experiences, we were less interested in prescribing particular consulting methods; instead, we wanted to cultivate shared knowledge and values centered on equity, access, and language justice among our staff. In fostering a critical awareness of the roles of language and the ongoing violence of literacy (see, e.g., Pritchard, 2017; Kynard, 2013; Stuckley, 1990), we hoped our team would develop values congruent with our language statement and, in turn, do good on these values within their consulting. We understood that our language statement had codified values essential to The Center but had not done the necessary work to enact those values. We came to recognize the self-work the language statement compelled us to do. Specifically, through this process, we came to terms with how language interacts with power, hegemony, and social structures in complicated ways. In fact, we challenged some deep-seated assumptions and values about what makes writing “good,” how ideas of “good writing” are shaped by social systems, and reimagined the role of a writing consultant. Through this (un)learning process, we recognized that we needed to create a professional development curriculum that pushed us away from performativity and closer to realizing our commitment to language justice.

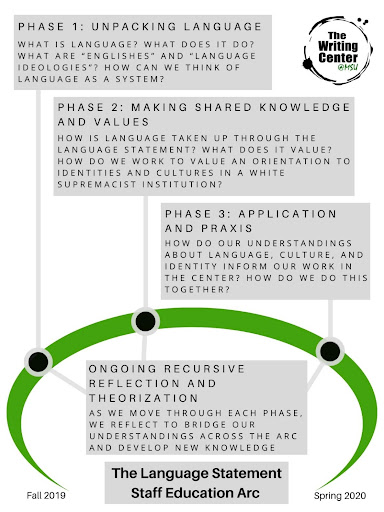

As depicted in the figure, our professional development curriculum consisted of three key phases. Overall, the first phase featured critical reflection on our collective experiences with language and power and how interlocking systems of power (e.g., racism, classism, ableism, and homophobia) sustain myths of “good” languaging. Specifically, considering our staff’s varied personal, professional, and disciplinary backgrounds, we intentionally designed interactive activities that invited our consultants to reflect on their experiences and values around language critically. For instance, during our first staff meeting of the year, we facilitated a reflective exercise using a series of structured writing and discussion prompts. These prompts included:

-

- When has language mattered in your life? Consider the way you talked, the words you said, accents, etc. How did people react? Did some react differently than others? How did you then react/feel?

- Has language ever mattered in class? In your written work or other assignments? In what ways? What did you do in response?

- Have you ever characterized someone else based on their language in some way? How? Why? What were the circumstances?

In short, through independent writing and small group conversations, consultants worked to (a) story their experiences with language and (b) understand the variety of structures (e.g., race, gender, class, region, and sexuality) that inform their languaging practices and ideas about language.

The second phase focused on building consultants’ critical awareness of the relationship between language and power. Toward this, we defined key concepts, including how exercising power through consultant positionalities and identities constructs the environment and, in turn, people’s material conditions. Specifically, to underline the sociopolitical contexts that propel language-based discrimination, we introduced Rosina Lippi-Green’s framework of language subordination. We relied on this framework because it provides concrete examples of the variety of ways language becomes subordinated, including how language becomes mystified, and how conformers are praised and non-conformers are vilified. Following this short mini-lecture on language ideology and subordination, we facilitated an interactive activity in which we invited consultants to analyze how language ideology and subordination play out in everyday artifacts, specifically several children’s books and an op-ed piece about accent reduction. In small groups, consultants read and discussed how they saw language ideology represented in the curated artifacts and then shared with the larger group. We used the following questions to guide this particular activity:

-

- How do you see language ideologies coming to bear on the artifact?

- What does the artifact “say” about language, power, and belonging?

- Do you see any evidence of language subordination? If yes, how so?

Ultimately, this exercise pushed consultants to further recognize how social structures and hegemony propel language ideology. They also named the ways language ideologies are reinforced across varied spaces and mediums (e.g., schools, literature, and popular media).

These snapshots of our language justice professional development arc showcase how we moved from self-work to (re)education and finally to practice. Indeed, it was centrally important for us to foreground critical reflection in these initial two stages, as we considered it integral to our staff’s learning that they reflect on their own experiences with language, including language oppression, and on the systems that shape their language beliefs, expectations, and practices.

In line with The Center’s queer-feminist ethos and the other phases of the professional development arc, we saw our staff development curriculum as a process of learning with a recursive opening and closing, not a top-down linear model of knowledge consumption. Accordingly, we conceptualized the final phase in line with hooks’ (1994) understanding of education as a mutual labor, where teachers and students learn in community with one another on the ground, shifting their positions constantly. Thus the final phase moved to concrete actions—how to honor our language statement and commitment to language justice in everyday praxis. As such, we facilitated communal knowledge-making activities, where we, as a team, brainstormed how to apply our commitments in practice and challenge prescriptivist pedagogies. We will continue to pay close attention to this last phase, as it will stretch on into future work in The Center for as long as need be, necessitating moments of opening to previous phases to reinterrogate positionalities before arriving back at practice.

Across these phases, consultants underwent significant developmental moments where we revisited previously held conversations and pushed ourselves to reorganize our thinking that modeled the transformative staff education we sought to deliver. For example, one of our long-time consultants, Mary, explained that the PD had opened her eyes to some of the problematic teaching practices she had used in the past in her role as a teaching assistant. Specifically, she explained how she used to tell students that they should not write how they speak and provided written feedback in line with this idea. However, after participating in this staff education, she has reframed the way she approaches providing students’ feedback and her expectations of what “good” writing looks/sounds like.

The various moments with consultants reflecting on themselves and their practice served as a signal that our professional development was having an impact. However, more importantly, the involvement of the staff in a communal conversation through scaffolded, ongoing professional development served as the beginning of new structures in The Center. Our goal at the onset was to work with the current consultants; however, throughout this professional development series, it became evident that The Center would need to always have the language justice (re)education for the foreseeable future. Our departure will continue to strive for that goal even if any individual consultant may arrive at new self-truths as Mary did. Until there is positive systemic change around language justice and writing centers, there will continue to be a need for language justice professional development. We will continue to depart.

Challenges and Reflections

Constraints of Staff Meetings, Time, Labor, and COVID-19

Despite our best efforts to design intentional, hopefully transformative, professional development programming for our staff, one of the most substantive takeaways was the increasingly sticky nature of this work. Reckoning with how power structures shape people’s literacy and language values within the limited time allotted for staff meetings proved challenging. Given our contingent workforce’s material realities—their time, space, and energy—we faced competing priorities. Furthermore, these meetings often produced more questions than answers, and consultants often wanted to know how they should concretely approach their work, even at the onset of these conversations. For myriad reasons, some of our staff seemed less invested in the intense labor of unlearning their complicity in language subordination (Lippi-Green, 2011). Additionally, in Spring 2020, COVID-19 forced The Center online, eclipsing our professional development plans. We tell this story because we do not want to romanticize our experience. And yet, language justice compels us to lean into the messy process of aligning who we say we are with what we uphold in policy and practice.

Enacting Symbolic Statements

Although we published our language statement after a long two years of researching, writing, and refining, we understood that this statement, like most statements, was largely symbolic. This statement signals what we value and, hopefully, sets an inviting tone for our clients, which is undoubtedly important. But actions realize said values. And so, we knew that until our staff understood, believed, and supported the message at the heart of the statement, it risked being performative. Invested in living into and enacting the commitments codified within this statement, we integrated the values throughout The Center’s practices, policies, and procedures, beginning with our hiring and onboarding processes and our staff’s continuing professional development. From there, we published a comprehensive consulting handbook, adapted the undergraduate consultant curriculum, reconfigured our graduate student mentoring program, overhauled our public-facing workshops, and launched multiple speaker series. By aligning The Center’s processes and operations with the language statement, we recognized the time, commitment, and planning required to start realizing calls for more just, equity-driven writing centers.

Next Steps Toward Forwarding Our Commitments

When we think about the language statement as an anchor document, we’ve come to see how important it is to name our values explicitly. This naming helps us to reflect our positionalities within our writing center as well as beyond it. Our clients and staff reflect the world beyond The Center, but we also help shape the world. And so, it is critical that we actively embody our espoused values and commitments. Our language statement and our corresponding professional development programming hold us accountable to our commitments to language justice and transformation in concrete ways.

In agreement with Greenfield (2019), writing centers of the 21st century have an ethical responsibility to build a better world. Greenfield writes:

A radical writing center defines itself through its critical examination of methods. This examination goes beyond cognitive or programmatic lenses to include sociopolitical lenses. A radical writing center remains open to changing and being changed by its methods. It remains open to the unknown. (2019, p. 125)

Writing centers must commit to radical politics centering language justice in and beyond the immediate domains. As Green et al. (2019) describe, we must do the work because people die due to racial and linguistic injustice. If writing centers have always been in the business of linguistic gatekeeping, then we must continually interrogate: how are we—in our methods and values—dismantling or reifying violent, white supremacist structures within the institution of higher education?

Ultimately, we came to understand that the real work of this statement was in providing us an entry point into the messy, uncomfortable, and rewarding process of unlearning and relearning. It wasn’t the destination but our departure; it led to labor-intensive, conflict-inducing work—work that matters, que vale la pena (Anzaldúa, 2009). And we invite you to join us.

References

Anzaldúa, G. (2009). Let us be the healing of the wound: The Coyolxauhqui imperative—la sombra y el sueño. In A. Keating (Ed.), The Gloria Anzaldúa reader (pp. 303-318). Duke University Press.

Baker-Bell, A. (2019). Dismantling anti-Black linguistic racism in English language arts classrooms: Toward an anti-racist Black language pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 59(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1665415

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge.

Boquet, E. (1999). “Our little secret”: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.2307/358861

Brannon, L., & Knoblauch, C. H. (1982) On students’ rights to their own texts: A model of teacher response. College Composition and Communication, 33(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.2307/357623

Brooks, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making students do all the work. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 15(6), 1–4. https://wlnjournal.org/archives/v15/15-6.pdf

Colquit, J. L. (1977) The student’s right to his own language: A viable model or empty rhetoric? Conference on College Composition and Communication, 25(4), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463377709369267

Conference on College Composition and Communication Committee on Language Policy. (1974). Students’ right to their own language. College Composition and Communication, 25(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/356219

Delpit, L. D. (1988). “The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children.” Harvard Educational Review, 53(3), 280–298. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.58.3.c43481778r528qw4

Faison, W. (2014, October 14) Reclaiming my language: The (mis)education of Wonderful. Digital Rhetoric Collaborative. www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2014/10/16/reclaiming-my-language-the-miseducation-of-wonderful/

Faison, W., & Treviño, A. (2018). Race, retention, language, and literacy: The hidden curriculum of the writing center. The Peer Review, 1(2).

Freeman, L. (1975). The students’ right to their own language: Its legal bases. College Composition and Communication, 26(1), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/356795

Green, N. (2018). Moving beyond alright: And the emotional toll of this, my life matters too, in the writing center work. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 15–34. www.jstor.org/stable/26537361

Green, N., Caswell, N., & Nordstrom, G. (2019, October 11). Language diversity in the writing center [Panel discussion]. Writing Center @ MSU, East Lansing, MI.

Greenfield, L. (2019). Radical writing center praxis: A paradigm for ethical political engagement. University Press of Colorado.

Greenfield, L. (2011). The ‘standard English fairy tale’: A rhetorical analysis of racist pedagogies and commonplace assumptions about language diversity. In L. Greenfield and K. Rowan (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 33–60). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk6s.6

Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (2011). Introduction: A call to action. In Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 1–14). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk6s

Grimm, N. M. (1999). Good Intentions: Writing center work for postmodern times. Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Grimm, N. M. (2011). Retheorizing writing center work to transform a system of advantage based on race. In Greenfield, L., & Rowan, K. (Eds.), Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change (pp. 75–100). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgk6s.8

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as a practice of freedom. Routledge.

Inoue, A. (2016). Afterword: Narratives that determine writers and social justice writing center work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1), 94–99. \http://www.praxisuwc.com/inoue-141.

Judy, S. (1978). Editor’s page: The students’ right to their own language: A dialogue. The English Journal, 67(9), 6-8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/815118

Kinloch, V. F. (2005). Revisiting the promise of students’ right to their own language: pedagogical strategies. College Composition and Communication, 57(1), 83–113. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30037899

Kynard, C. (2013). Vernacular insurrections: Race, Black protest, and the new century in composition-literacy studies. SUNY Albany.

Labov, W. (1975). Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lippi-Green, R. (2011). English with an accent: Language, ideology and discrimination in the United States. Taylor & Francis Group.

Lockett, A. (2019). Why I call it the academic ghetto: A critical examination of race, place, and writing centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2), 20–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/2679

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.2307/377047

Parks, S. (2000). Class politics: The movement for the students’ right to their own language. Refiguring English Studies. National Council of Teachers of English.

Pritchard, E. D. (2017). Fashioning lives: Black queers and the politics of literacy. Southern Illinois University Press.

Reising, B. (1997). Do we need a national language policy? The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, (70)5, 231–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1997.10543921

Rosa, J., & Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: Toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Language in Society, 46(1), 621–647. https://doi:10.1017/S0047404517000562

Rosa, J. (2019). Looking like a language, sounding like a race: Raciolingustic ideologies and the learning of Latinidad. Oxford Studies in Anthropology.

Scott, J. C., Straker, D. Y., & Katz, L. (2009). Affirming students right to their own language: Bridging language policies and pedagogical practices. Routledge.

Sledd, J. (1969). Bi-dialectalism: The linguistics of white supremacy. The English Journal, 58(9), 1307–1315. https://doi.org/10.2307/811913

Smith, A. (1976). No one has a right to his own language. College Composition and Communication, 27(2), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.2307/356981

Smitherman, G. (1995). Students’ right to their own language: A retrospective. The English Journal, 84(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/820470

Stuckley, J. E. (1990). The violence of literacy. Heinemann.

Williams, B. J. (2013) Students’ “write” to their own language: Teaching the African American verbal tradition as a rhetorically effective writing skill. Equity & Excellence in Education, (46)3, 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2013.808099

Writing Center @ MSU. (n.d.a). Language statement. https://writing.msu.edu/language-statement/

Writing Center @ MSU. (n.d.b). Vision statement. https://writing.msu.edu/about/vision-statement/.

Young, V.A. (2009). “Nah, we straight”: An argument against code switching. JAC, 29(1/2), 49–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20866886