Kyle L. Barron, University of Connecticut

Kathryn Warrender-Hill, University of Connecticut

Sophie Wallis Buckner, University of Connecticut

Psyche Z. Ready, University of Connecticut

Abstract

This article introduces the theoretical concept of “writing center space-time” and reports on an empirical study which finds that offering a diverse range of tutoring modes increases access to writing center resources. We encourage our fellow writing center practitioners to consider this proposed space-time framework to gain a more inclusive, more equitable, and ultimately more productive perspective on accommodating a diverse student body. Our project, at its core, is about access and equity, and we share details and outline data from our preliminary study in the hopes that other writing centers may be inspired to take up similar inquiries and expand tutoring services and modalities in other regions, locales, and institutional settings.

Keywords: Access, equity, UDL, tutoring, modalities, online tutoring, asynchronous tutoring, drop-in tutoring, in-person tutoring, writing center, disability studies, space-time, underrepresented students, marginal identities

Introduction

Several years ago, during a lively discussion about writing center spaces and temporality, the following question was posed to us: are writing centers a place or a practice? The question gave us pause as it brought into focus the historically complex issue of how writing centers position(ed) themselves on college campuses. Echoes of Elizabeth Boquet’s article “Our Little Secret” (1999) rang clear, as she had therein discussed how writing center identities metamorphose from resting on site to resting on method, and back again (p. 455). We thought about our own identities as tutors and administrators and how both place and practice, site and method, are inextricably bound to how we do our work and where our work lives. As we pondered the implications of this question, we were reminded that writing centers have a complex history of defensively and symbolically taking up space on college campuses, in part to ward against larger institutional assumptions of what writing center work should look like and where it should happen. Writing centers, justifiably, had to take up space to establish their presence and define their practice.

Space and place are recurring themes in writing center research. For instance, North’s iconic “Idea of a Writing Center” (1984) positioned writing centers as places where “we aim to make better writers, not necessarily…better texts” (p. 80) as opposed to the “proofreading-shop-in-the-basement” (p. 83). Centers have worked hard to reject the “fix-it-shop” model by building on the process movement and social turn in composition. Kenneth Bruffee (1984) did so by arguing for a collaborative, conversation-based model of tutoring to “[provide] a social context in which students can experience and practice the kinds of conversation that academics most value” (p. 91). This is echoed by Lisa Ede (1989), who claims that “as long as thinking and writing are regarded as inherently individual, solitary activities, writing centers can never be viewed as anything more than pedagogical fix-it shops” (p. 102). In a keynote conference address, Andrea Lunsford (1991) traces the lineage of writing centers being seen as “storehouses” and “garrets” and argues that, instead, writing centers should position themselves as “Burkean Parlors, as centers for collaboration.” These early efforts to argue for and establish writing center spaces and practices were enormously helpful for a field trying to create its own professional identity separate from, but related to, composition studies. It helped give writing center practitioners a language and a body of work to look to when negotiating the needs of their own centers. This theoretical lineage has helped make writing centers what they are today: collaborative, kairotic spaces for writers to work through their writing goals.

But as often happens when pioneering scholarship helps define a field, certain practices and beliefs eventually become accepted as a given, as unquestioned commonplaces. There are a number of prominent, entrenched commonplaces born from seminal work that we wish to revisit and deconstruct here and in our research. In the spirit of Bruffee and Ede, most writing center tutors are taught to use Socratic-like questioning methods to help guide students through thinking about their writing processes and goals. To that end, tutors are trained to be non-directive and hands-off—to let students do the work. We notice a few things about this practice: 1) it takes time to carry out this method of tutoring (sessions are typically between 30-60 minutes); 2) Socratic questioning makes many assumptions about the students we tutor; and 3) tutoring often happens, by default, in a generically furnished physical space. We’re not suggesting that any of this is inherently bad. Commonplaces can serve as constructive anchors for us to ground our practices or provide a sense of shared mission and responsibility, but they can also be problematic. We’ve begun to question how this standard approach might be limiting if it is the only way that students can access the writing center. Therefore, our research seeks to deconstruct and critique commonplaces that may create barriers for students by looking at: 1) the ways that writing centers deploy collaborative pedagogy; 2) the emphasis on physical spaces and face-to-face interaction; and 3) the often rigid and restrictive temporal frameworks that dictate session duration, scheduling of appointments, and synchronicity. As Lori Salem (2016) asks us to consider, who is not using the writing center because of our assumptions about how tutoring should happen?

Critiquing writing center spaces, and the work done there, is not a new discussion. Denny’s Facing the Center (2010) invites us to reflect on the complex identity writing centers inhabit in colleges, in the profession, and in their practices, writing that “writing centers themselves, the units and spaces that are home to our collective work, must also come to terms with identity in their own way” (p. 147). Jackie Grutsch McKinney (2013) addresses many of these same issues. She critiques “grand narratives” as traditionalist perspectives that view writing center work through a narrow lens and often neglect to consider the complex and ever-evolving work we do. Too often, these grand narratives don’t account for who or what is left out of the picture, and their repeated invocation serves to entrench lore, cementing commonplaces that dominate writing center practices. Another important critique of commonplaces is from Anne Geller’s work on fungible and epochal time in writing center work (2007). She constructively interrogates the time spent building rapport in writing center sessions. She points out that our literature is saturated with directives to build rapport and ease writers into the work of the session, in essence “swaddling the conference in a kind of comfort zone, keeping student anxiety at bay” (p. 35). The literature also doesn’t fully account for how much time that rapport-building takes away from the session—and, importantly, it relies on another established commonplace: that “comfort” is universally comfortable, and that it is required in the work we do. McKinney, parallel to Geller, urges writing centers to problematize what comfort means in our spaces. The commonplace assumption that “best practice” is a scheduled 30- to 60-minute in-person session where significant time may be spent building rapport is just that: an assumption. It implies that we know what makes students comfortable, that we know the best use of their time, and that we know what’s best for their writing. We don’t—at least not universally.

Our project, at its core, is about access and equity. It’s about making sure that writing center resources are justly distributed. We want to know if students are more likely to use the writing center if modes of tutoring are made more diverse. We began our study pre-pandemic by assessing a pilot “Flash Tutoring” program where students could drop in, without an appointment, to ask quick questions of a tutor. Our initial inquiry focused on session length and scheduling, but that research was cut short as the pandemic forced our center online. At that juncture, we decided to completely re-envision the project from the ground up, moving away from the two-dimensional Flash Tutoring angle to zoom out and capture a picture in a richer four-dimensional space-time. We also decided that while the pandemic year we spent fully online was an intriguing microcosm, it wasn’t an accurate representation of what writing center work might look like moving forward, as the return to campus slowly came to pass. We wanted to continue offering online tutoring sessions and begin piloting asynchronous tutoring sessions, while continuing and expanding Flash Tutoring. Our goal was to see if offering a broad variety of tutoring modalities would encourage visits from students who weren’t otherwise visiting the center.

If we go back to our opening question—are writing centers a place or a practice?—the obvious response is that they are both. But we believe, especially after witnessing the academic aftermath of the COVID pandemic, that the situation is far more nuanced than that, and it’s time for writing centers to rethink what is meant by place and to expand how practice is understood. By addressing place and practice more critically, we hope to decouple writing centers from the traditional, decades-long notions of place and practice that they have used to define themselves. In other words, we suggest, along with those who have already raised similar issues (Denton, 2017; Sanford, 2012; Fleming, 2020; McKinney, 2013) that it’s time to let go of the idea of the writing center as an exclusively physical space. Perhaps it’s time for writing centers to take up space whenever and wherever we are needed by writers, because, while our physical presence is still important, it’s the work we do with students, our practice, that matters the most. If our mission is still to make better writers (however we define that), does that mission require that it take place at a tutoring table?

Writing Center Space-Time: Framing Our Work

As we began our critical inquiry into modality and access, we realized we needed a framework to help us conceptualize what it meant to view writing center work as existing on multiple planes and in various spaces. In our conversations about tutoring experiences across many institutions and modalities, we began to realize that our practices are inevitably shaped by the spatial and temporal boundaries that we are required to work within. As such, we see the work of writing center practitioners as steeped in a kind of writing center space-time that is ever-present but rarely seen, acknowledged, or engaged with in an intentional manner.

Einstein’s theory of relativity, very simply speaking, firmly couples space and time. Philosopher Bertrand Russell explains that while traditional (read: dated) understandings of physics used the discrete terms “space and time,” evolutions in how we view our universe now insist that we embrace a notion of space-time instead. Russell elaborates:

Suppose you wish to say where and when some event has occurred—say an explosion on an airship—you will have to mention four quantities, say the latitude and longitude, the height above the ground, and the time…the three quantities that give the position in space may be assigned in all sorts of ways…but we must know the time as well as the place…We need four measurements to fix a position, and four measurements fix the position of an event in space-time, not merely of a body in space. Three measurements are not enough to fix any position. That is the essence of what is meant by the substitution of space-time for space and time. (p. 59-66)

In other words: the commonplace of space must also include an accounting for time. As Russell notes, the three quantities that designate space can be assigned in all sorts of ways, but we cannot fix any position without the fourth measurement of time being taken into account in the same moment of reckoning. The perspective we are advocating for argues that in writing center studies, we must begin to look at consultations as (per Russell’s terminology) events in space-time. This is not to negate or detract from spatial considerations, but rather to encourage the use of the richer framework of space-time, specifically the active interplay between space and time when thinking about how writing centers engage with writers.

In this imperfect space-time metaphor, our writers are points plotted on a coordinate system, and our writing center resources (in-person, online, synchronous, asynchronous, scheduled, drop-in, etc.) define the axes used and the ranges occupied. The writer’s location in this system is determined by when and where and how they want to engage with somebody on their writing, and if their point falls outside our operating hours or their proximity to a physical center, their needs and desires will go unmet. If we’re so focused on (limited by) commonplace and tradition that we’re only working with certain ranges of one, two, or three axes (think: a physical center that is open only in-person from 10am to 5pm), we’re missing all the writers (points) that fall somewhere on the coordinate system outside of our reach. In doing so, we’re limiting ourselves to, at best, a 3D rendering of what’s possible. When we engage our writers on all axes, offering sessions using the most robust combination of space, modality, and temporality that our local situations allow, we are more likely to catch writers where they are in the vastness of writing center space-time. In doing so, we evolve into a 4D space, becoming a tesseract instead of a cuboid.

Taking this further, by linking time and space together Einstein helped scientists understand that bodies (human or celestial) experience time differently depending on their proximity to the source of gravity. This is because gravity, as understood using the theory of relativity, bends space (think of a blanket stretched out, held at all four corners, with a bowling ball plopped in the middle). And when space is bent, time travels differently, and the way time is experienced is therefore relative to a body’s location in space (or on the blanket). This secondary layer to the space-time analogy is vital to understanding that each individual person (each mind, each body, each entity) experiences the writing process differently; individuals experience time and physical space differently, they react to the many variables in various ways, and they will have divergent expectations for what an ideal (read: comfortable and productive) writing center experience might be. It’s all relative.

Space-time may feel like a strange way to explore writing center work, but we see it as a useful metaphor for what our research strives to do. Scholars in other realms of study, notably in disability studies and universal design, have similarly considered the space and time dynamic. Engaging with writing center space-time is a call to reconceptualize, reframe, and expand the work of writing centers, and to re-imagine our commonplaces. As in the theory of relativity, we understand that the material reality of bodies of students and tutors (like gravity) “bends” (or shapes/reshapes) writing center spaces; but if we only ever use a linear or three-dimensional model to understand the interaction between bodies and space, we fail to fully recognize and appreciate how those bodies exist in space and how they experience time. Our writers, for example, may need writing support online, while situated in the accessible space of their homes, in order to avoid the physical obstacles and barriers of a college campus (Dolmage’s “steep steps”) as well as the anxieties and microaggressions many students experience in face-to-face spoken communication. Our research foregrounds the question: If we stretch our work into a fourth dimension, if we accommodate writers’ space-time—rather than asking them to accommodate ours—by offering multiple tutoring modalities, will we draw new writers into the center?

Space-Time, Access, and Universal Design

Universities and their writing centers must recognize the wide range of identities represented in their student populations, rather than relying on an imagined “default student.” Our critique of this default student draws on writing scholars (Baker-Bell, 2020; Canagarajah, 1999; Greenfield, 2011; Horner & Trimbur, 2002; Matsuda, 2006; Young, 2010; and many others) who have written about white language supremacy, feminist scholars (Cheryan & Markus, 2020), and disability scholars (Carter et al., 2017; Dolmage, 2017). Writing centers and academic programs were built for this default student: a white, cisgender male, nondisabled, neurotypical, single, childless, middle- to upper-class, early to mid-twenties, etc. The exhausting length of that list suggests the extremely narrow demographic represented by this default student and the many identities excluded when we design our programs and institutions for him alone.

Our work builds on recent scholarship that identifies the ableism of current writing center spaces and practices (Dembsey, 2020) and theorizes how to increase access in our centers for students with disabilities (Hitt, 2012; Rinaldi, 2015; Daniels, Babcock, & Daniels, 2020); it also expands on research like Anne M. Fleming’s (2020) article “Where Disability Justice Resides,” which explores how asynchronous tutoring sessions benefit writers who are autistic or neurodivergent. We argue that offering multiple tutoring modalities, framed using a rich backdrop of space-time considerations, will better serve students with disabilities, and like Fleming, we argue for a Universal Design approach to tutoring practices that accounts for all potential bodies that might use our space. The Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework calls for multiple means of engagement, representation, and action and expression to provide access through multiple avenues of learning. In our study, these avenues are the multiple session modalities.

Our conception of space-time intentionally dovetails with “crip time,” a concept that emerges from the disabled community and Disability Theory. Allison Kafer (2013) explains in Feminist, Queer, Crip that individuals with disabilities might need more time for tasks or to access services, for instance, due to slower mobility; lack of parking or public transportation; a dependency on caretakers, interpreters, or assistants; technology or device malfunction; ramps or elevators in inconvenient locations, etc. Access to asynchronous tutoring sessions helps students with disabilities avoid several of the physical barriers listed above, as students are not expected to walk across campus from a distant parking spot to physically enter the writing center; they will not have to face the obstacles of snowy sidewalks and unreliable public transportation; the immunocompromised will not be in an enclosed space with unmasked people. All three of our experimental modalities remove the obstacles to disabled bodies introduced by the physical space of the writing center.

But the barriers to writing center space (and all spaces) are more than just physical. Tara Wood, in an article on “Cripping Time” (2017), notes that we have to be careful how we construct time in instructional and support settings, as our instinct to “enforce normative time frames upon students whose experiences and processes” may run counter to instructional standards can be deleterious, and ultimately “disenfranchise students whose bodies and minds don’t adhere to expectations for commonplace pace” (p. 261). Kafer (2013) too touches on the many “ableist barriers” that disabled persons may encounter: for example, a random person gawking at your body or your gait, or being forced into a conversation in the elevator about why you continue to wear your mask, or the exhaustion of what Annika Konrad (2021) calls “access fatigue.” Students with disabilities need physical access to our centers but they also need access to a space free from discrimination and microaggressions. For many, that space is often best accessed from home. As Kafer (2013) notes:

Crip time is flex time not just expanded but exploded; it requires re-imagining our notions of what can and should happen in time, or recognizing how expectations of ‘how long things take’ are based on very particular minds and bodies. Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds. (p. 27)

This is where our nontraditional tutoring session modalities come in. A person experiencing unforeseen setbacks can “visit” the writing center in a more epochal way that accommodates how their bodies move through time and space. In the writing center, “bending” to meet the needs of writers with disabilities looks like, among other things, short, unscheduled, in-person “flash” sessions and online asynchronous appointments, both of which remove the possibility of “running late” as there is no set beginning or end of a session, and our online synchronous and asynchronous appointment modalities allow writers with disabilities to access our services from the comfort of their own homes, including the option of keeping their camera off.

We believe that an accounting for crip time and an expansion of the traditional understanding of a writer’s space-time will increase and broaden access to the writing center for all students, including those with disabilities. Importantly, the option to make a virtual or asynchronous appointment benefits every student at an institution. Nontraditional, low-income, or first-gen students who may be navigating challenging logistical circumstances (such as commutes, outsized financial burdens, or familial obligations) often benefit from the flexibility afforded by nontraditional modalities. Having the option to grab a remote or asynchronous tutoring session on the road, between shifts, or from home after preparing dinner or helping the kids with homework is an enormous boon. This is an example of the “curb-cut effect”: when a change created as an accommodation for people with disabilities ends up benefiting other groups of people. For example, while the pandemic shift to online-only education was difficult for many, some Black students preferred remote learning, because studying from home protected them from the oppressive inequalities experienced daily in face-to-face learning environments. While it may be a difficult pill for us to swallow, for some of our students, writing center spaces may not be as accessible, welcoming, or safe as we believe them to be.

Our Current Research

Research on Tutoring Modalities

The National Census of Writing’s Four-Year Institution Survey (2017) showed that while virtually all surveyed institutions offered scheduled face-to-face appointments, fewer than half (232 of 477) offered scheduled online appointments, only 10% (48 of 477) offered drop-in online appointments, and only 35% (166 of 477) offered any kind of asynchronous feedback. The survey also showed that a near-universal majority of institutions (99+%) had an average session length over 30 minutes, with 51% of those being 45 minutes or longer on average. It additionally showed that 28% of institutions said that fewer than 10% of their student population had a writing center consultation (85 of 305), 40% of institutions only engaged with between 10% and 25% (123 of 305), and only eight institutions surveyed, 2.5% of the total (8 of 305), claimed that half of their student body had a writing center consultation. Not a single institution reached more than 55%. Our two main takeaways from this data are that few centers are diversifying modality, and few centers are achieving high engagement numbers. As such, we see significant value in researching how a student population would react to having a wealth of space-time options available to them after previously having only a few traditional session modalities.

Institutional Research Context

In investigating how an expansion of writing center space-time affects access and equity, our current IRB-approved research project added multiple new modalities to our writing center’s programmatic offerings. In addition to our traditional scheduled, in-person tutoring sessions, we began offering scheduled, online synchronous tutoring, in-person drop-in tutoring, online drop-in tutoring, and asynchronous written feedback options. We hypothesized that the implementation of these additional modalities would broadly expand the choices our writers had, as well as broadly expand the reach of our writing center as an institutional entity. Our goal was to determine if that hypothesis would be supported by the data.

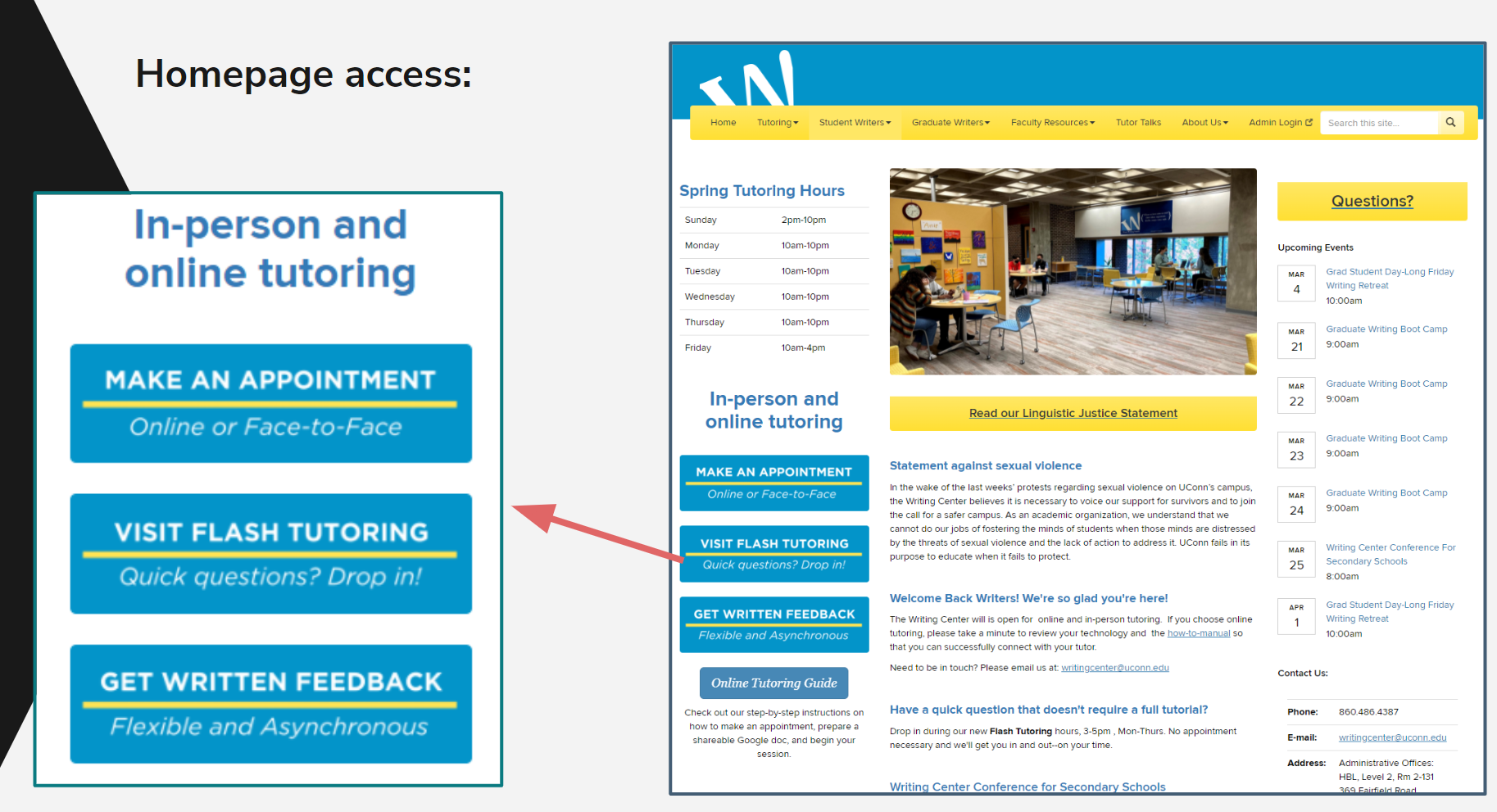

In redesigning Flash Tutoring (our drop-in service), we believed that the more hours we offered, the better the service would be. We also believed that if we could offer the service in-person, there was no reason we couldn’t also offer it online. In our initial 2019 research study we were only able to pilot the service 2 hours a day (10 hours a week in total). We view this as one of our original project’s failings, because when it was only available two hours a day (5pm to 7pm, for example), it was, for all intents and purposes, an appointment. The original Flash Tutoring service was arguably less flexible than a traditional appointment because the writer didn’t get to pick when the session was, instead being required to show up during the limited hours it was offered. In our re-imagination of the service, we argued for dramatically expanded hours, as many as we could possibly get, even asking to instead have a “float tutor” on shift who would be available for drop-in appointments any time the center was open. We also set up an online Flash Tutoring room via Blackboard Collaborate, monitored by the tutor. This kind of drop-in tutoring service is loosely modeled on Daniel Sanford’s “peer-interactive” example (2012), where writers are free to continue working or even consult with peers while a tutor circulates and fields questions. This was easily extended to an online space, and we placed a prominent link to it on our center’s homepage, directly below the link to our traditional scheduler (see Figure 1).

In designing our Written Feedback service, we sought to appeal to as many writers as possible by imagining a portal where they could submit their writing in under five minutes. We hoped that writers would read our FAQ and understand that it was meant to be a collaborative, conversational engagement with a tutor, and that achieving this asynchronous “conversation” would require them to answer a few questions to frame the feedback they’d receive. We also hoped to be able to offer as many of these appointments as there was demand (limit one per week per writer).

As with our online Flash Tutoring service, a prominent link to the Written Feedback service was displayed on the center’s homepage (see Figure 1). Some writing centers make their invitation to engage with diverse modalities far more visually blunt—the University of Arizona’s Writing Center being an exemplar—but we compromised with a solution that foregrounded the new offerings while maintaining the traditional look of the website.

Data Collection

Our study employs a mixed methods data collection approach that first invites all writers to take a quick 14-question survey that consists of multiple choice and open-ended questions. This survey is sent or offered to all writers at the conclusion of every session. At the end of the survey, respondents are invited (on an opt-in basis) to participate in a follow-up interview where they can elaborate on their tutoring experience and how it fit into their writing process. This research was approved by our institution’s IRB and data collection began in the Fall 2021 semester. We will be updating our protocols to include questions specifically about disability for data collection during the 2022-23 academic year. Our survey asks questions about modality preference, due date, experience with visiting the writing center, and collects demographic data. Our interview asks a range of questions about modality, agency, relationship to writing, and writing process. When interviews are complete, coding and data analysis will take place. These links provide access to our Survey Protocol and Interview Protocol.

Preliminary findings

In this section we present preliminary findings across our two IRB-approved research studies. Data on in-person, online, and asynchronous sessions is exclusively from the 2021-22 academic year. Data on Flash Tutoring spans both IRBs and is combined data from 2019-22. Our satisfaction metrics were high across the board, for all modalities (above 90% “good” or “excellent”), so we decided to not include that data in detail here.

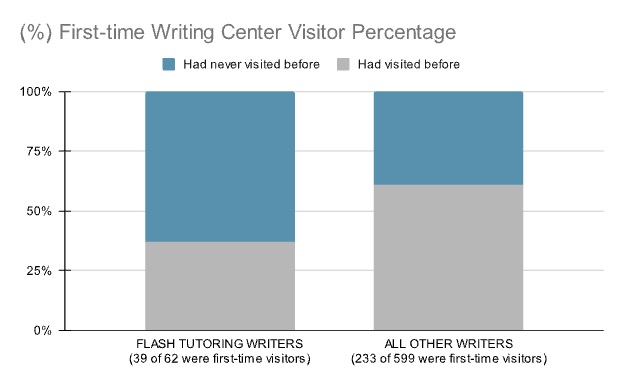

Out of 62 total Flash Tutoring respondents, 63% (39 of 62) said that they had never been to the writing center before. This is a remarkable statistic when compared to the broader pool of respondents where 61% of all other writers (366 of 599) had been to the writing center before. Of these first-time Flash Tutoring visitors, 77.1% were sophomores, juniors, seniors, or graduate students (dispelling concerns that this data simply reflected first-year students who hadn’t made it to the center yet). Together, these findings demonstrate that Flash Tutoring appears to appeal to a population of students that traditional tutoring modalities may not reach (Figure 2).

In the Written Feedback (WF) data, a few findings caught our attention. Out of 21 total Written Feedback respondents, 66% (14 of 21) said that they would only use the written feedback service. In that same vein, 71% (15 of 21) of WF respondents said that they had never attended any other session modality—only Written Feedback. This makes it clear that these writers were only interested in the WF service. The data (especially paired with other informal/anecdotal conversations we have had with writers) suggests that some writers simply prefer asynchronous tutoring, and if it isn’t an option, they will not use the writing center. Our research on Written Feedback is still in progress, and we hope to get more detailed, targeted feedback on this during the interview process.

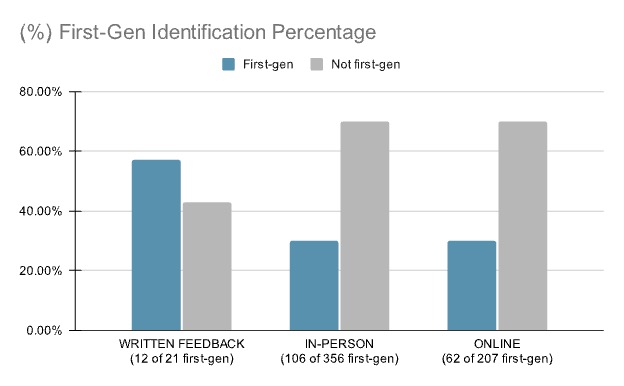

Another interesting Written Feedback finding was that a significant majority of WF writers identified as first-generation students. When asked if they were the first person in their family to go to a four-year college or university, 57% (12 of 21) said YES. This statistic stands out when it is noted that the first-gen data from all the other modalities heavily weighted towards the NO side: in-person, for example, showed 70% (250 of 356) were not first-gen, online showed 70% (145 of 207) were not first-gen. Written Feedback was the only modality to show this majority YES result (Figure 3).

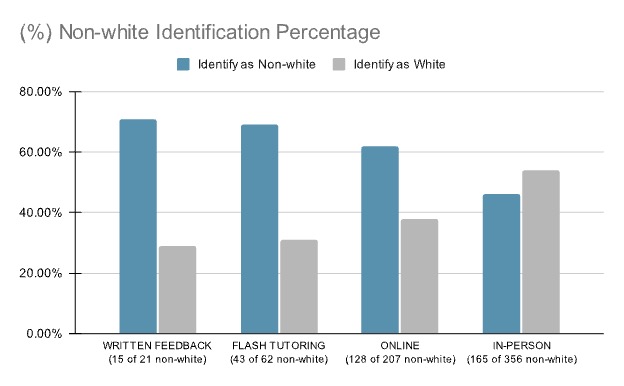

Yet another striking finding is that 71% (15 of 21) of Written Feedback respondents identified as non-white students. Only 6 of 21 identified as white. When asked “how would you describe yourself?” in relation to ethnicity, 38% chose Hispanic/Latinx, 24% chose Asian, 5% chose Indian, and the remainder white. The data was similar for Flash Tutoring respondents, with 69% (43 of 62) identifying as non-white. And again, for Online Tutoring respondents, a significant 62% (128 of 207) of online respondents identified as non-white. Our data showed that the more traditional in-person modality was the only modality where a majority (54%) of writers identified as white (191 of 356 respondents). This data suggests that white students trend toward traditional in-person tutoring, while non-white students trend toward Written Feedback, Flash Tutoring, and Online Tutoring (Figure 4).

The 71% non-white WF statistic and the 69% non-white Flash Tutoring statistic are even more remarkable when considering that our university is a PWI (Predominantly White Institution) with a student population that is 61% white. A 2020 study conducted at our campus titled “The Racial Microaggressions Survey” (sponsored by our Institute for Student Success and Office for Diversity and Inclusion) found that out of 1,129 students of color surveyed, 77% reported that race relations at our university ranged from “a little problematic” to “extremely problematic.” In that same survey, students of color rated spaces across campus where they feel uncomfortable (or avoid entirely due to discomfort), with classroom spaces and academic departments ranking #2 and #5. While these findings necessitate an introspective assessment that looks hard at why students are feeling this way, it isn’t surprising that they may be looking for ways to get the engagement and feedback they desire in less traditional (less “commonplace”) formats or modalities.

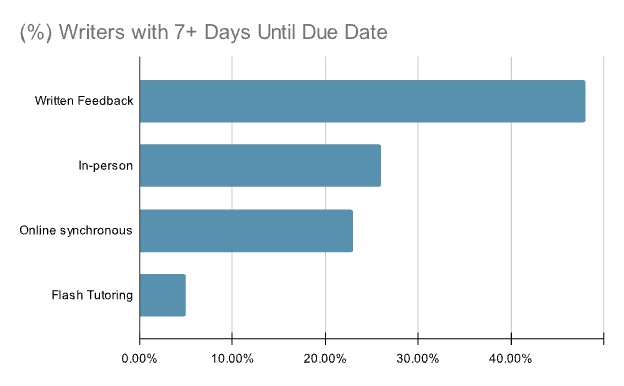

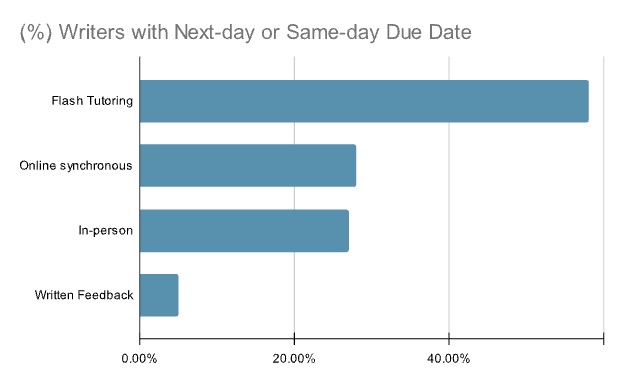

We also found some interesting data when we began digging into time and due dates in these alternative modalities, and at what point in the writing process students come to the writing center. When Written Feedback writers were asked when their project was due, 48% (10 of 21) of respondents said that they had more than a week to turn it in, while 76% (16 of 21) said that they had more than four days until it was due. These statistics were way out of line with the rest of the data we collected. In any of the other modalities, it was comparatively rare for writers to visit with more than seven days until the due date. Only 26% (93 of 356) of in-person writers said they had more than seven days, while 23% (48 of 207) of online writers said they had more than seven days, and only 5% (3 of 62) of Flash Tutoring writers said they had more than seven days (Figure 5). While it is possible to explain some of this deviance by acknowledging that it takes several days for a writer to submit a piece of writing to the WF service and receive feedback, we don’t think that that fully accounts for a shift this large.

Taking this same metric and applying it to the other end of the spectrum, 58% (36 of 62) of Flash Tutoring respondents said their project was due that very day or the next. It was, again, comparatively rare for anyone to visit with an assignment due that soon in any of the other modality categories: in-person data showed 27% (99 of 357) had a due date of today or tomorrow, online data showed 28% (58 of 207) had a due date of today or tomorrow, and WF data showed that a mere 5% (1 of 21) had a due date of today or tomorrow (Figure 6). Average due dates for the traditional online and in-person categories fell very heavily within the 2 to 7 day window.

These interesting outlier temporal findings from both Written Feedback and Flash Tutoring services suggest that time constraints play significantly into a writer’s choice of modality. A service like Flash Tutoring likely appeals to writers with an urgent time crunch, while Written Feedback appeals to writers with a longer project runway who might want eyes on their work at several points during the process. These findings align with our original hypotheses and make logical sense. We hope to gain additional insight on issues of time and modality during our interview process. These findings also lead us to believe that there are further benefits to fully integrating an asynchronous Written Feedback service, including the possibility that this longer project runway may encourage writers to get an earlier start on projects and seek feedback more often throughout their composing process.

Most of the findings discussed so far have involved the new, non-traditional modalities (drop-in and asynchronous). That’s in part because those findings were the most surprising and in part because the data suggests that those are the modalities that most help us stretch the boundaries of writing center space-time to reach writers we don’t reach otherwise. It’s important to reiterate, however, that none of this research is meant to detract from how vital traditional modalities are. Traditional scheduled in-person and online tutoring sessions are incredibly popular and remain the modality of choice for most writers. Both online and in-person modalities have their devout followers. Out of all online tutoring respondents, 40% (82 of 207) said that they would only come for online tutoring; out of all in-person tutoring respondents, 57% (204 of 356) said they would only come for in-person tutoring. This emphasizes that while alternative modalities may be key for reaching new populations, maintaining existing traditional modalities and innovating within those boundaries is crucial to keeping writers engaged.

The scope, scale, and timing of our study (limited to one institution, one writing center, multiple pilot projects, all spanning the unique transition from pre-pandemic to pandemic and then post-pandemic practices), simply does not create a data set that achieves formal statistical significance (nor did we set out to achieve that). The applicability of these findings will vary from institution to institution, population to population, and we invite and encourage further research studies, with larger participant pools and more sophisticated statistical analysis, to further investigate the encouraging conclusions we have arrived at.

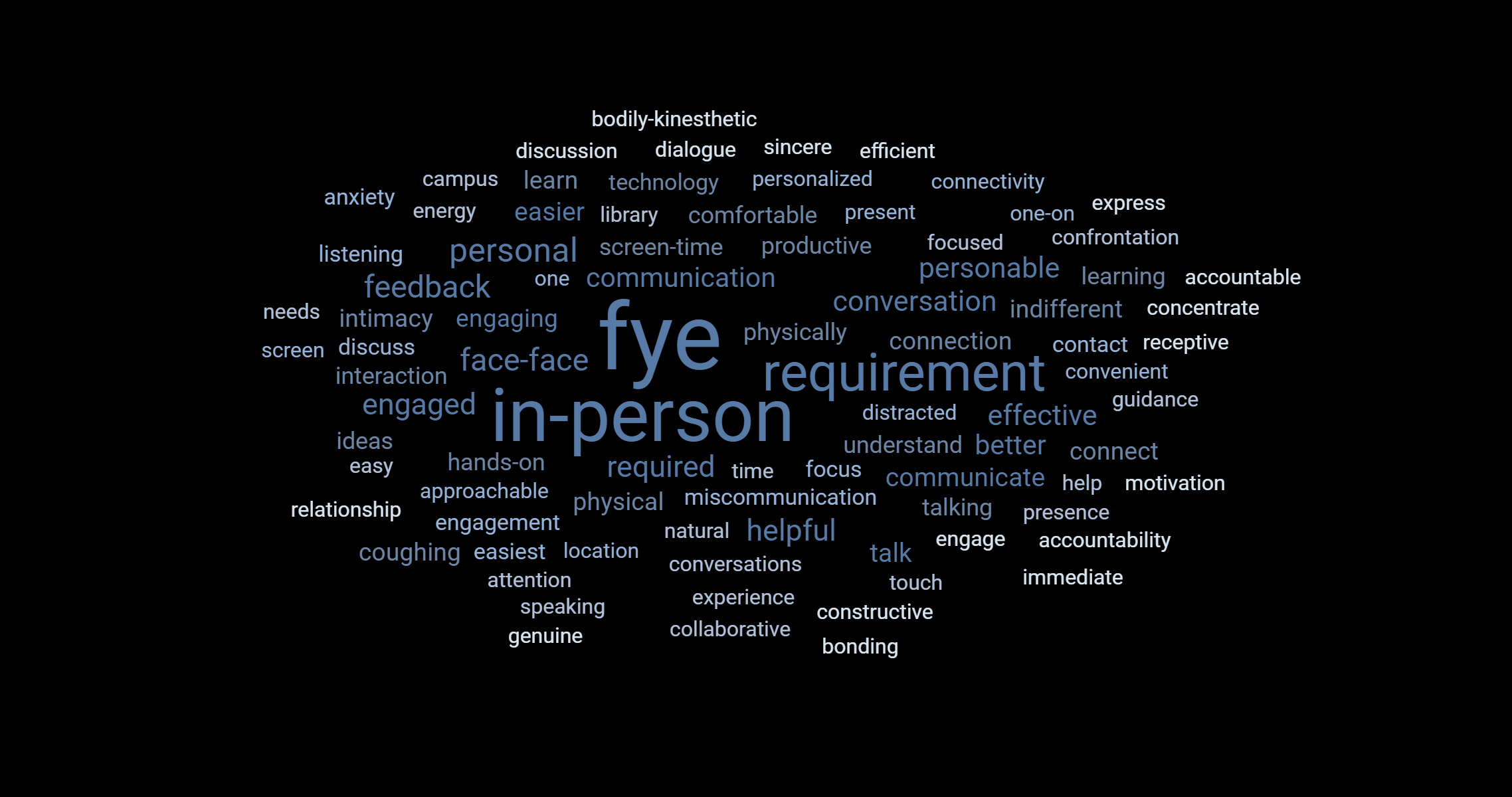

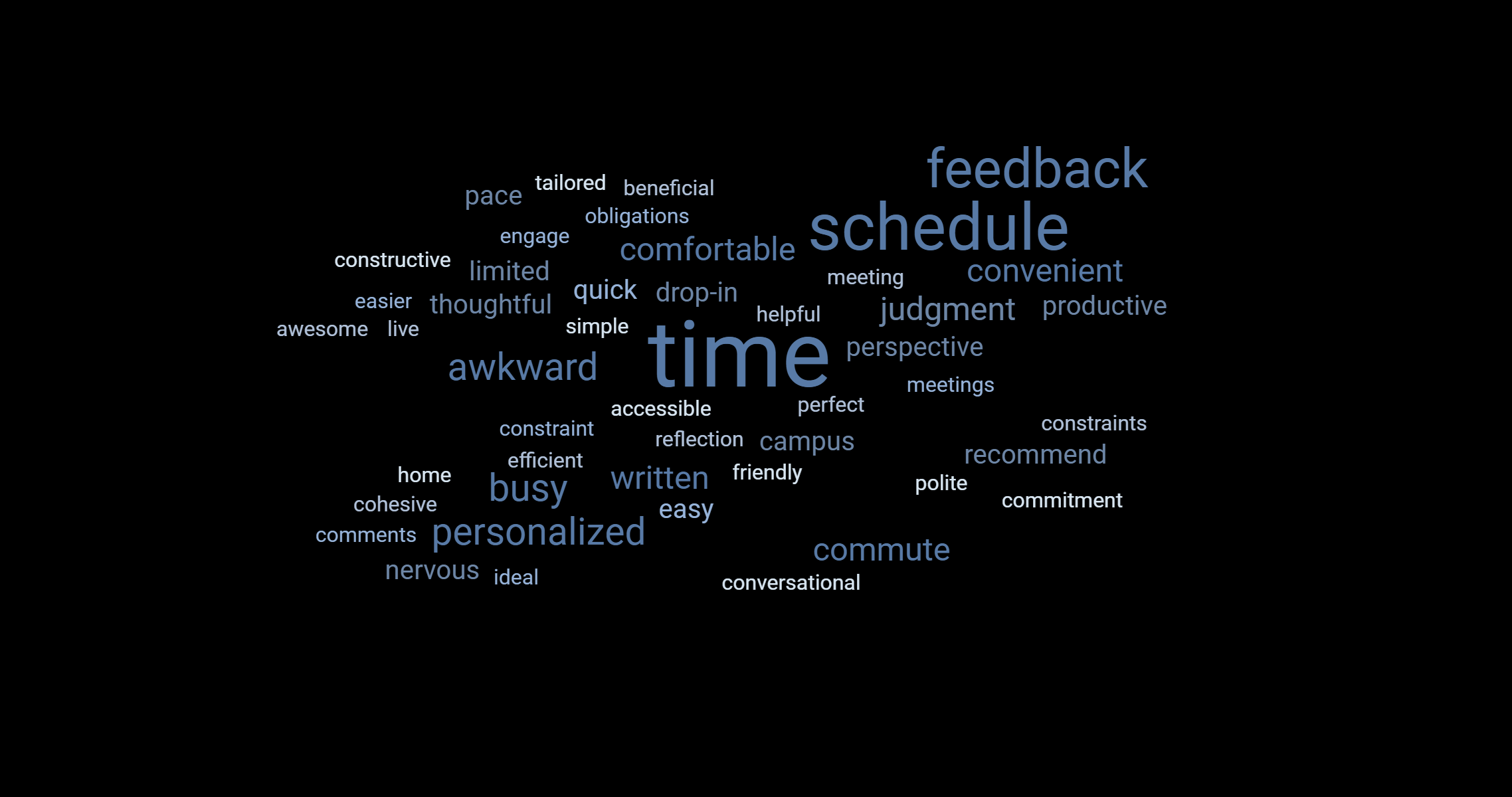

Word Clouds

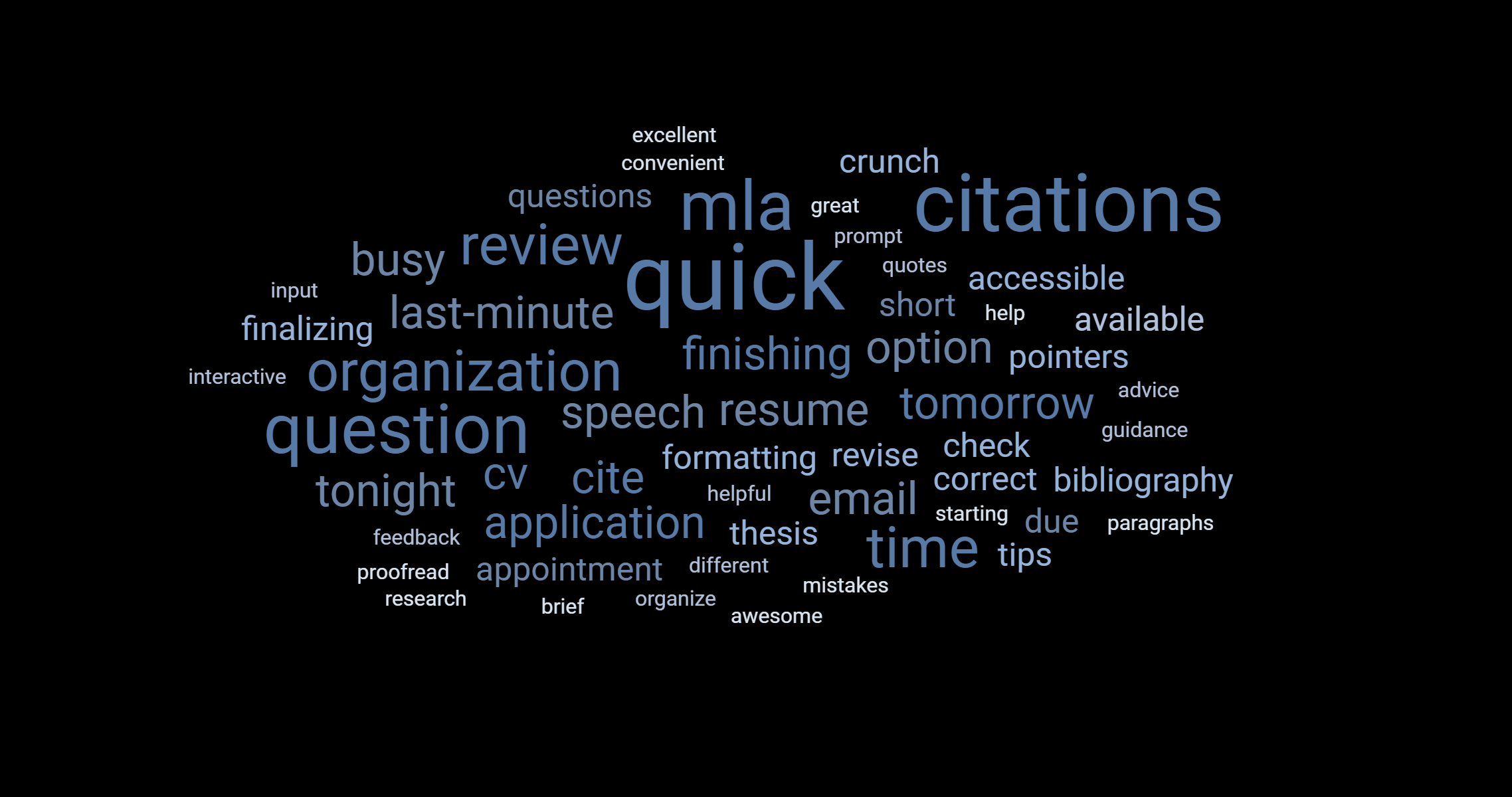

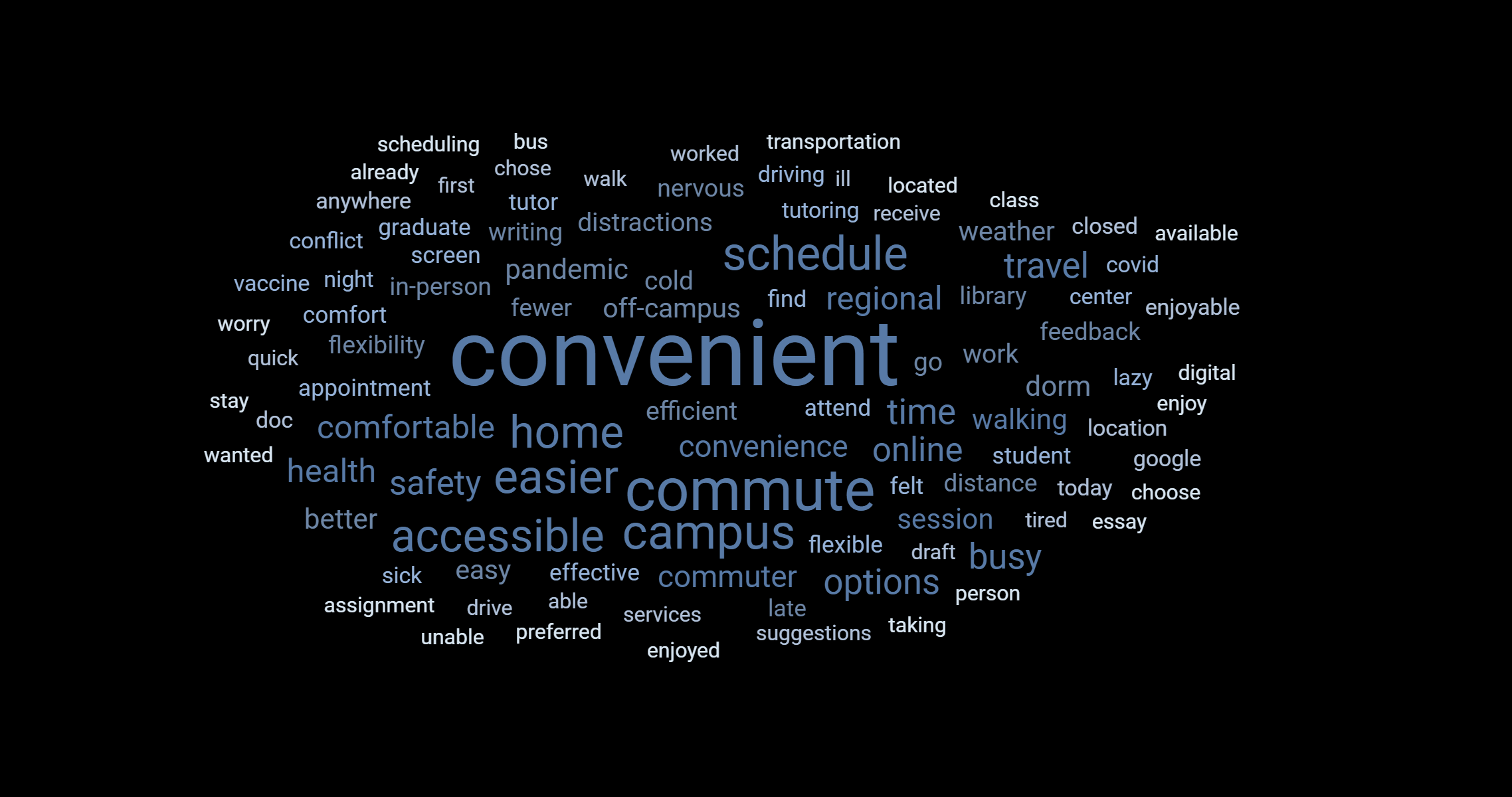

Our survey provides several open-ended questions for respondents to voice their opinions, and while we have not yet coded these responses, we believe that the data in those over 600 responses is valuable and tells an incredible story about modality and access. To frame this data for our readers, we have created a set of word clouds, one from each modality, that provide a glance at patterns and themes that are emerging.

Figure 7 represents the data from our Flash Tutoring respondents, and as is to be expected, many of the words that emerge relate to time: “quick,” “last-minute,” “tomorrow.” This supports our hypothesis that flash tutoring provides a time-conscious option for writers. Additionally, certain words speak to the type of writing that Flash Tutoring attracts: resumes, applications, CVs, and works cited pages. While it’s too early to say there is anything more than their characteristic shortness of the texts at play here, it is not lost on us that these genres are laden with gatekeeping conventions. It is possible that Flash Tutoring appeals to students who may be less familiar with academic and professional writing conventions, and this line of inquiry will be particularly important as we continue to investigate ways to increase access for marginalized or underserved writers.

Figure 8 represents the data from our online tutoring respondents. One word stands out as a clear frontrunner: convenient. “Convenience” is a word that academia often casts in a negative light. The word connotes laziness, wastefulness, impatience, carelessness, and many other vices. It is not a coincidence that these words have also been weaponized against many of the populations we have discussed in previous paragraphs (Carter, Catania, Schmidt, & Swenson, 2017). Yes, diversifying tutoring modality creates more convenient options, and our data supports this claim: the words “convenient” or “convenience” show up 78 times throughout the short responses from our survey. While multimodality is a convenience for our default, privileged student, this convenience may be vital to those who struggle to exist in a world that often forgets or even actively threatens them. For students with disabilities, “convenience” may actually mean “access.” Other words that hold particular interest to our inquiry are those that refer to travel, like “commute,” “walking,” or “off-campus.” These words suggest that online tutoring appeals to writers who would not be able to access the physical space of the writing center due to location. We also take note of words related to sickness or safety, like “weather,” “ice,” “pandemic,” “health,” “safety,” and “sick.” Several students disclosed illness and how they were able to access the writing center without endangering themselves or others by opting for online tutoring. The word “anxious” here sometimes referred to the anxiety of being in public spaces during a pandemic but also referred to writers’ feeling more at ease in their own homes.

Figure 9 represents the data from our in-person tutoring respondents, and it provides an interesting take on why some choose in-person appointments at the writing center. The most prominent word is “FYE,” which stands for First-Year Experience at our institution. This program has long partnered with our writing center, and FYE instructors are asked to require students to visit the writing center as part of their introduction to resources on campus. This is the only exception to our general policy of not allowing required visits. Despite this policy, we still see that the two most prominent words in our in-person word cloud are “FYE” and “requirement.” This finding is interesting because we did, for a while, offer online FYE appointments, yet the online word cloud doesn’t reflect the same focus on FYE or the word “requirement.” It appears that first-year students are more likely to attend these FYE sessions in-person, but we can’t be sure whether that reflects a student preference or the preference (or recommendation, or requirement) of the individual FYE instructors who assign the project. Our data cannot answer this question, but we would be remiss if we overlooked the value of in-person writing center appointments for first-year students who are familiarizing themselves with a new home on campus. Other words that are worth mentioning are words to do with sociality and relationships, like “personal” and “intimacy.” These words support the body of knowledge in writing center studies that encourage a personal touch in tutoring. We also see some evidence that preference for in-person tutoring can be a matter of access. Many students indicated that they can pay better attention in-person. The word cloud shows this with words like “attention,” “engage,” “easier,” “concentrate,” etc. Words like “attention,” “concentrate,” and “efficient” speak to a specific way that sharing a space with a person engages the mind. This speaks to a specific learning style associated with space and physicality. Other respondents mentioned space directly with words like “library” or “campus.” Responses often disclosed that respondents already frequented the spaces they mention, which made physically attending a tutoring session easy for them. The short responses to our survey data about the in-person model show the value of offering a physical space in terms of access.

Figure 10 represents the data from our Written Feedback respondents and the data seems to reflect many of the same time concerns that the Flash Tutoring respondents had, with words like “schedule,” “time,” “busy,” and “quick” featuring prominently. Writers also used words like “awkward” or “anxious” to describe how they feel about talking verbally or face-to-face with people. This supports our hypothesis that writers might prefer modes of tutoring that allow them to avoid social interactions that cause undue anxiety.

These word clouds tell a story about the value of each modality according to our survey respondents. While traditional-length in-person and online sessions were the most popular, they were popular for different reasons. Online tutoring offers access in the sense that it extends the reach of the writing center, overcoming the physical barrier that distance and inaccessible structures create, while the in-person tutoring sessions provide access for some through relationship and engagement in a specific physical space. Both Flash Tutoring and Written Feedback provide access across time because they allow for students to bend the time they spend with the writing center to fit into the time they have available. These word clouds, and the data they are based on, have helped us to uncover more ways that the flexible uses of time and space in the writing center can increase access.

Study Implications and Limitations

Study Limitations

Our study has its limitations, as do our findings, and execution of the project has not been without missteps, indecision, and a smattering of “duh” and “oops” moments. One of our biggest concerns is the way that the project translated from paper to practice. We spent significant time mapping out an implementation plan for the new services we hoped to offer, but our vision did not come to fruition as we had hoped. In a perfect world (both for the sake of our research and for the sake of achieving the access and equity our research is rooted in) we would have been able to deploy these new services exactly as they had been imagined. However, as it is with most things on an institutional or societal scale, especially in regard to improving access and equity, change is slow and grindy, and we had to accept incremental progress. Even getting a drastically scaled-back pilot program off the ground required hurdling many roadblocks ranging from budgetary issues, staffing issues (some of which were related to delayed hiring and pandemic concerns), pedagogical disagreements over the effectiveness of asynchronous tutoring, and divergent views on how far centers could or should stray from the commonplaces that had carried them to where they are. Upon initial implementation we had a Flash Tutoring service that was only offered 4 hours a week (2 hours twice a week) in Fall 2021, and 8 hours a week in Spring 2022 (both below the arguably inadequate 10 hours we originally had back in 2019). As a result, our Flash Tutoring dataset is far from reaching saturation. We hope to remedy this shortcoming as we continue to make our case for expanding the service to resemble a true drop-in model.

Another related limitation of our study is our ability to create and sustain full institutional buy-in. In the same way that accessibility shouldn’t be an afterthought in architecture (think rickety wooden ramps laid over the top of towering flights of stone stairs) we believe that accessibility can’t be an afterthought or an add-on in course design or programmatic offerings. A small-scale “test” or “pilot,” may not adequately address or understand access needs. Offering a service in brief spurts or windows, when convenient, is, at best, a kind of patchwork accessibility, and it doesn’t allow the program a chance to flourish or build a student following. To be successful, programs like these need time, resources, and support to gain institutional traction, and this is best done through strong, sustained advertising, with full administrative buy-in, and a foundational shift in the commonplaces that guide decision-making. Doing so will provide a better chance for increased student awareness, instructor buy-in, and the building of a strong user following. If you can generate this buy-in in your context, we believe you are more likely to see programmatic success and encouraging results.

A final shortcoming or limitation of our study is our lack of an explicit question about disability identification in the first iteration of our surveys. We hoped that writers would disclose disability or access information in the open-ended question fields, but we didn’t want to guide their hand, influence the survey data, or pry and make respondents feel uncomfortable with questions where disability is foregrounded in a way that felt invasive or unnecessary. In retrospect, our very hesitance to ask about disability directly represents a broader problem: a reticence to openly discuss disability, which results in many studies like ours failing to gather data about disabled people. The bottom line for us, in retrospect at least, is that we wished we had added an explicit survey question about disability, and we have added that question to our latest version of the survey.

Study Implications

The results from our preliminary study have wide-ranging implications. The most obvious implication we draw is that offering a variety of tutoring modalities invites new students to the writing center. This is an important finding as it provides justification for researching these modalities further. Denton (2017) encourages the field to move beyond lore when it comes to asynchronous online tutoring, and turn to research, and we believe that this applies to the other modalities we investigated as well. There were a couple of areas we believe are worthy of further exploration based on our findings:

While some of our reporting numbers were low, we found it particularly interesting that students of color and first-gen students were more likely to use the non-traditional modality options. Some students who used our Written Feedback service claimed they would only use that service. We believe this warrants further investigation to better understand the needs of these students and how to best serve those needs through a variety of tutoring modalities. But we also believe that better understanding of tutoring modality preferences would be necessary to further deconstruct our assumptions about what works best for students in general and certain populations of students in particular. For example, our word clouds suggest that asynchronous tutoring in particular offers writers a sense of ease and comfort in place of the judgment and awkwardness they experience during in-person, face-to-face meetings. While we had a small number of Written Feedback respondents, their responses suggest that something happens during face-to-face meetings that feels, in some sense, threatening to some writers. Whether these responses stem from writer insecurity or tutor approaches is difficult to say, but it is worth further inquiry. Additionally, time is a recurrent theme through several of our word clouds. The service students chose was often influenced by when assignments were due or other obligations students have outside of school. Writing centers should investigate how writing centers can better fit into students’ writing lives and ecologies to better understand where and how to meet them where they are. Lastly, as noted in our Study Limitations section, there were identities and populations we did not explicitly capture as part of our research. In particular, we believe it’s important to continue to investigate how tutoring modalities can support students with disabilities and multilingual writers. There’s still more to be learned about how different tutoring modalities mediate students’ writing growth and learning.

Our interpreted findings, and our assertion that centers should diversify their tutoring modalities, should not be read as an attempt to steer centers away from traditional modalities, but rather to include and invest in other ways of engaging with student writers. At the heart of what we are advocating for is innovative expansion of writing center space-time to meet as many writers as possible where those writers are at. We encourage writing centers to pursue their own investigations into access, equity, and modality to see if a local expansion of space-time benefits their student writers.

Conclusion

As universities continue the push to “return to normal” in this pseudo-post-COVID moment, we see writing centers and higher education at a critical juncture of decision-making. Do we jump at the chance to return to our cozy writing centers, embracing the normalcy such spaces might create for admin and staff? Or do we reflect and learn from our pandemic trials, forced though they were, to evolve and meet the needs of a student body who appear to find themselves increasingly at home in their homes or in alternative spaces? Our research and experience over the last several years has convinced us that while writing centers are both a place and a practice, neither of those things is static. Our practice and the places where we deploy it must be fluid and evolve with the writers we serve.

Our article narrates our center’s journey to redefine itself to better meet the needs of the student body. During that journey, there has been discomfort, struggle, and mourning for “how things used to be.” We believe that this discomfort should not be read as a sign to revert and return to the safety of our commonplaces, of what we have always done; we believe these discomforts are growing pains, representing an evolution in the places and practices of writing centers. Writing centers have fought hard to take up space on the university campus, and many of us may resist what feels like “giving up” that space any time we tutor off the hourly schedule or beyond the four walls of the center. Instead of resisting this evolution, we urge our colleagues to embrace the shift toward multimodality and recognize it for what it is: an expansion and an extension that will better support more writers.

Our initial research suggests that our original assumptions (that diversification of tutoring modality increases accessibility to and equitable distribution of writing center resources) are plausible, if not likely. As the march toward “normal” continues, we hope that our research shows the value of expanding into alternative modalities in writing centers, and we hope this research inspires additional investigation from the broader writing center community. In doing so, writing studies scholars can learn more about how alternative modalities facilitate student learning and how we can best meet students where they are. We hold fast to our assertion that centers must expand their conception of writing center work in order to take full advantage of all four dimensions of a robust writing center space-time.

Author Biographies

Kyle L. Barron is a PhD candidate at the University of Connecticut, where he served as Assistant Director of the Writing Center for three years. He is currently teaching writing and rhetoric while working on a dissertation that investigates how composition programs can better prepare students to navigate complex, technical, often controversial information ecosystems in civil society. His research interests include scientific and environmental rhetoric, technical communication, writing centers, disability studies, and access.

Kathryn Warrender-Hill is a PhD candidate at the University of Connecticut, where she has served as an Assistant Director in both the Writing Center and First-Year Writing program. Her dissertation looks at the relationship between writing and technology, though her research interests range from research methodologies, writing centers, and writing pedagogies.

Sophie Wallis Buckner is a PhD student at the University of Connecticut where she has worked at the writing center and as a First-Year Writing instructor. Her research encompasses writing center work as well as creative writing in the classroom.

Psyche Z. Ready is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Connecticut, with an emphasis in Writing Studies and Disability Studies. Her work at the Writing Center as the Coordinator for Graduate Writing Support has inspired her dissertation research in supporting disabled graduate student writers.

References

Baker-Bell, A. (2020). Linguistic justice: Black language, literacy, identity, and pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315147383.

Boquet, E. H. (1999). “Our little secret”: A history of writing centers, pre- to post-open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463–482. https://doi.org/10.2307/358861

Bowen, M. E., Mazzeo, J. A., & Russell, B. (1979). Space-Time. In Writing about science (pp. 59–66). Essay, Oxford University Press.

Bruffee. (1980). Two related issues in peer tutoring: Program structure and tutor training. College Composition and Communication, 31(1), 76–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/356637

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2012). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

Carter, A. M., Catania, R.T., Schmitt, S., & Swenson, A. (2017). Bodyminds like ours: An autoethnographic analysis of graduate school, disability, and the politics of disclosure. In S. L. Kerschbaum, L. T. Eisenman, & J. M. Jones (Eds.), Negotiating disability: disclosure and higher education (pp. 95–114). University of Michigan Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.9426902.10

Cheryan, & Markus, H. R. (2020). Masculine defaults: Identifying and mitigating hidden cultural biases. Psychological Review, 127(6), 1022–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000209

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Utah State University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt4cgqnv

Denton, K. Beyond the lore: A case for asynchronous online tutoring research. The Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 175-203.

Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Academic ableism: Disability and higher education. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9708722

Dolmage, J. (2015). Universal design: Places to start. Disability Studies Quarterly, 35(2). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v35i2.4632

Denny, H., Nordlof, J., & Salem, L. (2018). “Tell me exactly what it was that I was doing that was so bad”: Understanding the needs and expectations of working-class students in writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 37(1), 67-100.

Ede, L. (1989). Writing as a social process: A theoretical foundation for writing centers? The Writing Center Journal, 9(2), 3–13. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43444122

Fleming, A. (2020). Where disability justice resides: Building ethical asynchronous tutor feedback practices within the center. The Peer Review, 4(2). https://thepeerreview-iwca.org/issues/issue-4-2/where-disability-justice-resides-building-ethical-asynchronous-tutor-feedback-practices-within-the-center/

Geller, A. E. (2005). Tick-tock, next: Finding epochal time in the writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 25(1), 5-24. https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1569

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., & Boquet, E. H. (2007). Everyday writing center: A community of practice. University Press of Colorado.

Greenfield, L. & Rowan, K. (Eds.). (2011). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. University Press of Colorado. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.lib.uconn.edu/stable/j.ctt4cgk6s

Hitt, A. H. (2012). Access for all: The role of dis/ability in multiliteracy centers. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 9(2), 1–7. http://www.praxisuwc.com/hitt-92

Hitt, A. H. (2021). Rhetorics of overcoming: Rewriting narratives of disability and accessibility in writing studies. National Council of Teachers of English.

Hooks, B. (2014). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

Horner, B., Lu, M. Z., Royster, J. J., & Trimbur, J. (2011). Opinion: Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English, 73(3), 303-321. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25790477

Horner, B. & Trimbur, J. (2002). English only and U.S. college composition. College Composition and Communication, 53(4), 594–630. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512118

Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press.

Konrad, A. (2021). Access fatigue: The rhetorical work of disability in everyday life. College English, 83(3), 179-199. https://library.ncte.org/journals/ce/issues/v83-3/31093?fbclid=IwAR076DprOAk7UJl60FTveHvUAzbnVwsEgSOVCQg413UjZYxPdRRo4zi8uI0

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. The Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43441887

Matsuda, P. K. (2006). The myth of linguistic homogeneity in US college composition. College English, 68(6), 637-651. https://doi.org/10.2307/25472180

McKinney, J. G. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. University Press of Colorado.

National Census of Writing. (2017) Four-year institution survey. National Census of Writing Blog. (n.d.). Retrieved July 30, 2022, from https://writingcensus.ucsd.edu/survey/4/year/2017

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446. https://doi.org/10.2307/377047

Ries, S. (2015). The online writing center: Reaching out to students with disabilities. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 13(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/ries-131

Salem, L. (2016). Decisions… decisions: Who chooses to use the writing center? The Writing Center Journal, 35(2), 147-171. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43824060

Samuels, E. (2017). Six ways of looking at crip time. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(3), https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v37i3.5824

Sanford, D. (2012). The peer-interactive writing center at the University of New Mexico. In Composition Forum (Vol. 25). Association of Teachers of Advanced Composition. http://compositionforum.com/issue/25/new-mexico-interactive-wc.php

The UConn Racial Microaggressions Survey. (n.d.). https://rms.research.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2719/2021/01/UConn-Racial-Microaggressions-Survey.pdf

The UDL guidelines. UDL. (2021, October 15). https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Wood, T. (2017). Cripping time in the college composition classroom. College Composition and Communication, 69(2), 260-286. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44783615

Young, V. A. (2010). Should writers use they own English?. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 12(1), 110-117. https://doi.org/10.17077/2168-569X.1095