Rebecca Babcock, University of Texas Permian Basin

Abstract

This study reviews the current underlying theories relevant to writing centers as well as the research methods being used in the early 21st century. The first section covers the theories used in writing center scholarship from the 1980s onward based on influential articles and texts. The second section covers published research both in the Writing Center Journal (WCJ) and other publications from 2010 onward and discusses the current state of research methods. Readers may not be aware of some of the fine divisions of theory; for example, the distinction between collaborative learning and social constructivism. Researchers may benefit from the overview of methods, which covers the most popular and current methods (survey and textual analysis) and promising but little-published research methods, such as ethnography.

Keywords: collaborative learning, social constructivism, writing as a social process, Zone of Proximal Development, scaffolding, cognitivism, feminism, transfer of learning, threshold concepts, tutoring encounter, social and environmental justice, survey, mixed methods, textual analysis, descriptive studies, theoretical research, archival research, quasi-experiment, quantitative methods, narrative inquiry, grounded theory, case study, usability, ethnography

Writing Center Theory and Research: A Review

This article surveys the underlying theories and methods at play in writing center research. Stephen North, in The Making of Knowledge in Composition (1987), noted that in the field of rhetoric and composition there was “no unanimity on important issues” and that “it seemed as if the field did not have a core or a center: there seemed to be no way to frame its central problems, nor any method by which to set about trying to resolve them” (n.p.). Writing center research is not in this position today, but taking a step back and looking at the existing threads of theory and research can do for writing centers what North suggested for composition: frame the field’s central problems and develop methods to try to solve them. To be sure, the word “problems” can be misunderstood in the same way that many students misunderstand the word “critique.” By problems I do not mean troubles or negative circumstances, and I do not think North did either. It is more like a math problem, in that a problem is a research question that needs to be solved. An overview of this content would take another article. In this article I attempt to frame the field’s central beliefs/values in terms of research methods and theories.

1: A Review of Theories Influencing Writing Center Practice and Scholarship

Eric Hobson, in “Maintaining Our Balance: Walking the Tightrope of Competing Epistemologies” (1992), called the search for the one true theory of writing centers as a “hopeless effort” (p. 108) and explained that writing centers do not need to choose just one theory: all proposed theories can be considered valid. Lisa Ede, in “Writing as a Social Process: A Theoretical Foundation for Writing Centers?” takes this explanation a step further: “Practice without theory, as we know, often leads to inconsistent, and sometimes even contradictory and wrongheaded, pedagogical methods” (1989, p. 4). Despite this warning, as I tell my students, there is no atheoretical tutoring or teaching. Some sort of theory—pedagogical, political, philosophical—is being enacted whether or not the person chooses to acknowledge it. In what follows, I describe the major theories that have influenced—and continue to influence—writing center scholarship and practice. These categories are based on evidence from the literature rather than on my (or others’) opinions on what they should be. I present them in a rough chronological order. Other orders are possible.

1.1 Collaborative learning refers to people learning together as equals; it is active learning and stands in opposition to the banking model of education. Kenneth Bruffee’s “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind’” and “Peer Tutoring and the ‘Conversation of Mankind’” (1984a, b) are foundational documents, and collaboration is still represented in contemporary writing center theory. Donald McAndrew and Thomas Reigstad (2001) explained that “collaborative learning organizes people not just to work together on common projects but, more importantly, to engage in a process of intellectual, social, and personal negotiation that leads to collective decision making” (p. 5). The use of peer tutors is based in the theory of collaborative learning. Tutor and writer work together probing, questioning, evaluating, and discussing the work at hand. Tutors also learn from the process: “Both writer and tutor grow as writers because they collaborate on the process and the product of writing” (McAndrew & Reigstad, 2001, p. 6).

1.2 Social constructivism/constructionism is a post-modern theory that posits knowledge does not exist “out there” but is constructed by individuals and groups in communication. Andrea Lunsford’s famous article “Collaboration, Control and the Idea of a Writing Center” brought social construction to the fore in 1991, framing the ideal writing center interaction as a Burkean Parlor[1] event. Even though collaborative learning and social constructivism have been conflated many times in the literature (e.g., Murphy, 1994), they are distinct. It is possible to collaborate on a project that has top-down objectivist parameters, in which case knowledge would not be socially constructed even though the work and learning is collaborative. John Nordlof critiqued social constructivism, stating that sometimes the information is “out there” in the form of MLA requirements, etc. Moreover, Nordlof argued that social constructivist theory does not “clarify tutoring approaches [or] provide impetus for research” (2014, p. 45).

1.3 Writing as a social process is the theory that writing itself is a social act (as opposed to being learning and knowledge, which the first two theories deal with). Lisa Ede convincingly argued for this theory as it relates to writing centers back in 1989, maintaining that theories of collaborative learning did not go far enough. According to Ede, if writing is individual then collaborative learning is “unnatural” since only “beginning or second-best writers would need the support and collaboration that in-class peer groups and writing centers provide” (p. 6). McAndrew and Reigstad (2001) classified these theories as “talk and writing” (p. 4), but the prevalence of social media in today’s world provides evidence that this social process can also take place via text over a computer. Frank Smith (1987) has written of joining the literacy club as a metaphor for writing as a social process. Writing center tutoring allows students to join the academic literacy club through their interaction with a tutor.

1.4 The Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), created by Soviet Psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the 1930s, proposes that a learner can achieve more in the presence of a more capable peer, even if the peer does nothing besides be present. A related Vygotskian contribution is the idea that children need to use speech when performing tasks beyond their level of difficulty. The writing center tutorial interaction is implicitly based on these theories: the use of talk is needed to accomplish difficult tasks, and “the concept of the…ZPD provides a productive lens for describing tutoring strategies in writing center conferences” (Mackiewicz and Thompson, 2018, p. 4). Similarly, Nordlof (2014, 2020) determined through his research that ZPD was an underlying theory of writing center tutoring and scholarship. Rebecca Day Babcock, Kellye Manning, Travis Rogers, Courtney Goff, and Amanda McCain (2012) came to the same conclusion using a grounded theory approach through which they found most of the examined studies were based on a Vygotskian model where learning happens in the presence of a more capable peer.

Vygotskian theories are demonstrated in many articles without being explicitly referenced, including Tom Truesdell’s “Not Choosing Sides: Using Directive and Non-Directive Methodology in a Writing Session” (2007) and Peter Carino’s “Power and Authority in Peer Tutoring” (2003). In “Negative Feedback as Regulation and Second Language Learning in the Zone of Proximal Development,” Ali Aljaafreh and James Lantolf described a 13-step heuristic showing levels of directivity ranging from the learner acting independently to the tutor “provid[ing] examples of the correct pattern” (1994, p. 471). Although their continuum relates to lower-order concerns, it demonstrates the non-directive/directive binary is actually not a binary but two poles on a continuum, and that, according to Vygotskian theory, the level of assistance or directivity are based on the needs of the tutee. The two “poles” can be and are accommodated by the same theory.

1.5 Scaffolding is the process whereby learners achieve what they are capable of through assistance, achieving more than if left alone to complete the task. Scaffolding was first proposed by David Wood, Jerome Bruner, and Gail Ross (1976), who defined it as a “process that enables a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts” (p. 90). According to Wood et al., the scaffolding process has six steps, each of which have clear analogues to writing center tutoring: 1. Recruitment (getting the learner interested in the task); 2. Reduction in Degrees of Freedom (simplifying the task); 3. Direction Maintenance (keeping the learner on task); 4. Marking Critical Features (pointing out where the learner is on track or off track in relation to the goal); 5. Frustration Control (reducing stress); and 6. Demonstration (modeling).

According to Isabelle Thompson (2009), the Vygotskian encounter includes scaffolding. Thompson discussed direct instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding, which are based on terms developed by Jennifer Cromley and Roger Azevedo (2005) in research about adult literacy. Direct instruction involves giving answers and telling the tutee what to do. Cognitive scaffolding involves breaking down tasks, giving hints, and asking, “What’s next?” (Thompson, 2009, p. 423). Motivational scaffolding involves a tutor providing feedback and encouraging a student to continue. Other scholarship that addresses scaffolding in the writing center includes Jo Mackiewicz and Isabelle Thompson’s “Motivational Scaffolding, Politeness, and Writing Center Tutoring” (2013), which links scaffolding and politeness in tutor talk; Talk about Writing (Mackiewicz & Thompson, 2018), a book-length study based on concepts of instruction and cognitive and motivational scaffolding strategies used by experienced tutors; and Neal Lerner’s The Idea of a Writing Laboratory (2009b), which links scaffolding to a master/apprentice model of learning that includes reflection.

1.6 Cognitivism is a theory that “attempts to equate writing proficiencies with stage-models for thinking and views writing as problem solving” (Carino, 1995, p. 126). Although writing centers have not embraced cognitive theories over the years, cognitivism has been taken up by composition studies. According to Sarah Liggett, Kerri Jordan, and Steve Price, “while this model [Flower & Hays] has influenced writing center pedagogy, writing center researchers have not developed a cognitive process model of tutoring” (2011, p. 77). As such, I predict that the cognitive model will have a resurgence. Interested readers should consult the collection Contemporary Perspectives on Cognition and Writing edited by Patricia Portanova, Michael Rifenburg, and Duane Roen (2017), the chairs of the Conference on College Composition and Communication Standing Group on Cognition and Writing.

1.7 Feminism is based on the belief that all people are equal and invests in the dismantling of hierarchies. McAndrew and Registad argued that writing center tutoring is a form of feminist teaching because ideas of equality inform peer tutoring and that “tutor and writer work toward a common goal” (2001, p. 7). In Women’s Ways of Knowing, Mary Field Belenky, Blythe Clinchy, Nancy Goldberger, and Jill Tarule (1986) explained the concepts of “connected teaching” and “teacher as midwife” in which connected teachers assist students in bringing out their own ideas rather than acting as dispensers of knowledge. Midwife teachers (or tutors) “support their students’ thinking, but they do not do their students thinking for them or expect the students to think as they do” (pp. 217-18). A seminal article on feminism and tutoring is “The Politics of Tutoring: Feminism within the Patriarchy” by Meg Woolbright (1993).

Feminism can be applied to more than just tutoring. Michelle Miley in “Feminist Mothering: A Theory/Practice for Writing Center Administration” (2016) applies the concept of feminist mothering (as opposed to patriarchal mothering) to writing center administrative work. In this model the mother/writing center director maintains an outside identity, insists on shared partnership, and raises children/tutors with feminist values. Miley further discusses feminist theory and its connection to writing centers in her chapter “Bringing Feminist Theory Home” (2020).

1.8 Transfer of learning means taking something someone has learned and using it in a similar or different context. This concept suggests that we cannot teach skills in isolation; instead, we must explicitly tell students how they can use these skills in other contexts. Bonnie Devet (2015) provided a primer on transfer theory and research from the domains of educational psychology and composition and explained how transfer applies both to consultants and to their work with student writers. In addition, Heather Hill (2016) applied transfer to the context of tutor training by instructing tutors to engage in explicit transfer talk with tutees to make sure tutees understand a writing concept before moving on. Hill discussed more about transfer in writing centers in her 2020 chapter in Theories and Methods of Writing Center Studies. Pam Bromley, Kara Northway, and Eliana Schonberg (2016) conducted a study on transfer and found that all in all, students do engage in transfer from writing center work to other contexts.

1.9 The theory of threshold concepts posits that novices must grasp certain foundational understandings when entering a discipline. In writing studies, the concepts are: writing is an activity and a subject of study; writing speaks to situations through recognizable forms; writing enacts and creates identities and ideologies; all writers have more to learn; and writing is always a cognitive activity (Adler-Kassner & Wardle, 2015). In “Threshold Concepts in the Writing Center: Scaffolding the Development of Tutor Expertise,” Rebecca S. Nowacek and Brad Hughes posited an additional threshold concept for writing centers—that of experienced, effective conversational partners for writers regularly inhabiting the role of “expert outsider” (2015, p. 181)—and relate threshold concepts directly to scaffolding tutor development and knowledge. Sue Dinitz, writing in WLN, also discussed “Changing Peer Tutors’ Threshold Concepts about Writing” (2018).

Soon we will likely see scholarship discussing threshold concepts in light of tutee knowledge. In fact, Nowacek’s and Hughes’ 2015 chapter discussed how tutors might use threshold concepts to guide reluctant or misguided writers to better understandings and to help faculty understand the content of the discipline of writing studies. Lisa Cahill, Molly Rentscher, Jessica Jones, Darby Simpson, and Kelly Chase used ideas suggested by Nowacek and Hughes to develop their own “set of beliefs” to guide their writing center work (2017, p. 14).

1.10 Writing center as concept and writing center as place/space. Most studies have looked at tutoring methods rather than writing centers as—conceptual or real—places or spaces (Boquet, 1999); however, some types of theorizing look at the writing center as a conceptual space. For instance, Bonnie Sunstein (1998) discussed the writing center tutorial as a kind of pedagogical “liminal space” where people can talk freely about language and writing. Writing centers also can be liminal textually, spatially, culturally, professionally, and academically/institutionally when writing centers are positioned on a borderland—sometimes erased, sometimes enhanced by their in-between positioning. Anis Bawarshi and Stephanie Pelkowski (1999) suggested applying Mary Louise Pratt’s “Contact Zone” metaphor for the writing center to counteract the dangers of writing centers co-opting students’ language and writing and replacing them with an uncritical standard. In the writing center contact zone, students and tutors are encouraged to critique and analyze the subject positions imposed on them by and through academic discourse.

1.11 The tutoring encounter. Babcock et al. (2012) developed a theory of the tutoring encounter by using grounded theory to analyze almost 60 qualitative studies of writing centers published between 1983 and 2006. What follows is their expression of this theory:

Tutor and tutee encounter each other and bring background, expectations, and personal characteristics into a context composed of outside influences. Through the use of roles and communication they interact, creating the session focus, the energy of which is generated through a continuum of collaboration and conflict. The temperament and emotions of the tutor and tutee interplay with the other factors in the session. The confluence of these factors results in the outcome of the session (affective, cognitive, and material). Wolcott (1989) put it well when she wrote that “each conference represents a unique blending of variables—tutor personality, tutor priorities, student personality, student background, and student text” (p. 25). (2012, p. 11-12)

Concrete examples of this theory of the tutoring encounter occur widely in writing center publications and Babcock and colleagues are currently testing it against real data (2019).

1.12 Social and environmental justice. Other burgeoning theories are social and environmental justice. For example, social critique and activism have resulted in recent movements to bring multiculturalism, postmodern perspectives, and political activism to the forefront of writing center theory and research. Harry Denny (2010) wrote of the intersections between various identities (race, class, gender, nationality) and writing center work. Anne Ellen Geller, Michele Eodice, Frankie Condon, Meg Carroll, and Elizabeth Boquet (2007) brought in concepts of tricksters, time, a learning culture, anti-racism, and communities of practice to our understandings of how writing centers operate and how directors and tutors can work together to foster a learning culture. Greenfield and Rowan (2011), in their award-winning edited collection, presented more food for thought at the intersection of racism and writing centers, especially foregrounding issues of language and institutional racism. Romeo Garcia’s “Unmaking Gringo Centers” (2017) is also an article worth reading on this subject.[2]

2: A Review of Writing Center Research Methods

Writing center practitioners have long been interested in and concerned with research. In 1984, North called for writing center practitioners to examine what actually happens in tutoring sessions through descriptive case studies. More recently, research has been strongly promoted by the International Writing Centers Association (through grants and awards) as well as scholars in the field. For instance, Paula Gillespie, Alice Gilliam, Lady Falls Brown and Byron Stay produced Writing Center Research: Extending the Conversation in 2002, providing frameworks and models for would-be researchers; Rebecca Babcock and Terese Thonus published Researching the Writing Center: Towards an Evidence Based Practice in 2012 (revised edition 2018), providing an overview of what research has been done and a framework for further studies; Liggett, Jordan, and Price brought forth “Mapping Knowledge-Making in Writing Center Research: A Taxonomy of Methodologies” in 2011; and Jackie Grutsch McKinney published Strategies for Writing Center Research in 2016, providing a step-by-step introduction for beginning and experienced researchers alike. Most recently, Jo Mackiewicz and Rebecca Babcock edited the collection Theories and Methods of Writing Center Studies (2020). In the following sections, I provide a review of historical and current writing center research methods for readers to form a better understanding of both the past and present condition of writing center research.

2.1 A brief history of writing center research. The first call for writing center research came in Lindquist’s dissertation (1927; quoted in Lerner, 2006) when he called for research by writing laboratory supervisors to determine effective teaching methods. A flurry of theses and dissertations were done at the University of Chicago between 1924 and 1936 (Lerner, 2009a), and studies in this period were by and large experiments or quasi-experiments where groups of students were taught using one or another method and results were compared (Lerner, 2007). For example, Essie Chamberlain’s 1924 thesis studied high school classes using the “recitation” and “supervised study” methods. Chamberlain found the recitation method, which equates to a workshop approach in which students read and critiqued each other’s work, to be superior to the supervised study method (students working independently with periodic teacher conferences). The first published research study related to writing centers was by Warren Horner (1929), based on his 1928 dissertation. The experiment compared the laboratory method and the recitation method. The laboratory method consisted of all writing taking place in the classroom along with teacher-student conferences. The recitation method classes used peer review as well as lectures and demonstrations about writing and discussions over readings. All writing was completed at home with students logging in their time spent working. Horner found a very small gain in writing skills among the laboratory group, but the significant finding was that they spent half the time to achieve the same results.

According to Lerner (2009a), after the 1920s and 1930s, writing center research seemed to drop off the map, with only two dissertations completed between 1940 and 1970. Again, in the 1970s, research emerged that was mostly experimental and quasi-experimental. Also introduced around this time was theoretical work on writing centers, such as Jeanne Simpson’s dissertation, “A Rhetorical Defense of the Writing Center,” which appeared in 1982. After North’s 1984 call for research on tutoring sessions, qualitative research increased—still mostly in dissertations (Lerner, 2007). Janice Neuleib also called for additional research in 1984. Although she called for case study research, the protocol she described resembles teacher research as she suggested tutors should take careful notes on the students they tutor, do a needs assessment, prioritize issues, tutor the student, assess what happened, and make future plans.

A research explosion began in the 1990s with more and more scholars and practitioners turning their attention to empirical, data-driven research in writing centers. This is most easily seen in Lerner’s dissertation bibliography (2009a), since dissertations are mostly a research genre. According to Lerner’s bibliography, up until 1980, 14 PhD dissertations had been written on writing centers and labs, jumping to 19 in the 1980s alone, 37 in the ‘90s and 72 in the first decade of the 21st century. In fact, most writing center research, historically and currently, took place in dissertations, much of which has not been published (Liggett, 2014).

2.2 Current trends in research methods. In 1987’s The Making of Knowledge in Composition, Stephen North presented his version of the types of research being done in composition studies at the time. Recently, other typologies of writing center research have emerged, most notably from Liggett, Jordan, and Price (2011) and Lauren Fitzgerald and Melissa Ianetta (2016). Fitzgerald (2012) used similar typology (Historical, Theoretical, Empirical) in “Writing Center Scholarship: A ‘Big Cross-Disciplinary Tent.’” These typologies give an overview of the field and allow novice researchers and scholars to situate the research they are contemplating, both as consumers and producers. Such taxonomies are inevitably imperfect and suffer from exclusion (what does not neatly fit) and permeability (research that bridges more than one category).

In “Theory, Lore, and More: An Analysis of RAD Research in WCJ, 1980-2009” Dana Driscoll and Sherry Wynn Perdue (2012) investigated research published in WCJ in its first thirty years. They found that not much research that could be considered Replicable, Aggregable, and Data-Driven (RAD) had appeared in the pages of WCJ. In fact, only 16% of the articles could be categorized as RAD research according to their rubric. However, Mackiewicz and Thompson, writing in 2018, found that “over the past three years, more articles discussing RAD or using RAD methodology have been published in The Writing Center Journal than the number appearing for the 29 years from 1980 until 2009” (p. 1).

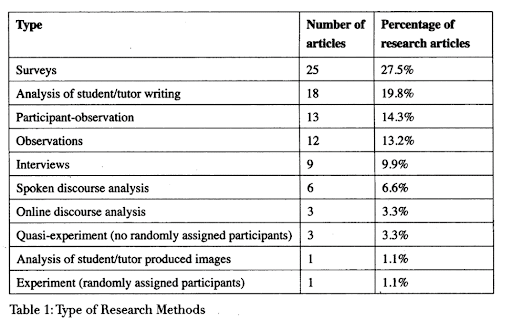

I extended Driscoll and Perdue’s research of WCJ articles by identifying which research methods were used between 2010-2015. I also sampled publications other than the core writing center venues through a search of Academic Search Complete using the keywords “Writing Center” and “Research” to find articles published between 2010-2015. Later I added WCJ articles published in 2016-2018 and other relevant studies to illustrate the categories. I did not attempt a quantitative analysis similar to Driscoll & Perdue (2012). In the subsequent sections, I categorize the research methods within this dataset. Although some of the methods described below are entire research frameworks, sets of guidelines that come as a package (Holton & Walsh, 2017), I am including them alongside methods to offer the reader an understanding of research approaches being used in the field resulting in publication. These research “packages” are known as methodologies. They typically encompass approach, theory, and method. Interview, observation, and analysis of text are the qualitative methods which are the tools used in various methodologies. Action research, case study, grounded theory, and ethnography are all methodologies based on these methods with various theoretical approaches and aims. Readers interested in more information on methodology can consult such works as Peter Smagorinsky’s “The Method Section as Conceptual Epicenter in Constructing Social Science Research Reports,” Theresa Lillis’s “Ethnography as Method, Methodology, and ‘Deep Theorizing’: Closing the Gap Between Text and Context in Academic Writing Research,” and Methods and Methodology in Composition Research, edited by Gesa Kirsch and Patricia Sullivan.

2.2.1 Survey has always been a popular method in writing center studies and continues to be. Surveys are usually quantitative but they can be qualitative as well with the use of open-ended questions. Stephen Neaderhiser and Joanna Wolfe (2009) used surveys quantitatively in “Between Technological Endorsement and Resistance: The State of Online Writing Centers.” A qualitative survey was conducted by Bethany Bibb (2012), in which she surveyed tutors and instructors about grammar instruction. Of note is that Bibb was an undergraduate when she conducted this study and that it appeared in an all-undergraduate issue of WCJ. Also appearing in this issue was another survey-based study by Jennifer Nickaly (2012) about consultant guilt. Another notable survey is Anne Ellen Geller and Harry Denny’s “Of Ladybugs, Low Status, and Loving the Job: Writing Center Professionals Navigating Their Career” (2013). Kathleen Coffey, Bridget Gelms, Cynthia Johnson, and Heidi McKee (2017) surveyed students and consultants to look at collaborative writing teams and the role of tutor/consultant as facilitator. Sarah Banschbach Valles, Rebecca Day Babcock, and Karen Keaton Jackson (2017) surveyed writing center administrators for demographic information, some of which, like race, age, and native language, had never been gathered before for this population.

2.2.2 Interviews involve some level of personal contact between the researcher and participants and are typically conducted in person, by phone, via webcam, or in some cases via email. Some interviews involve learning from a famous scholar, such as “Writing Center Work Bridging Boundaries: An Interview with Muriel Harris” by Elizabeth Threadgill (2010) in the Journal of Developmental Education. In a similar vein, Stacy Kastner (2017) conducted an interview with Michael Spooner. Other studies use interview as the main means of data collection such as The Working Lives of Writing Center Directors by Nikki Caswell, Jackie Grutsch McKinney, and Rebecca Jackson (2016). Cilla Dowse and Wilhelm van Rensberg (2015) used questionnaires and interviews to study a week-long graduate student workshop on proposal writing during which non-native English-speaking students worked with each other in small groups and individually with tutors.

2.2.3 Mixed methods research is the combination of qualitative and quantitative data, notably suggested for composition studies by Cindy Johanek (2000). Several subsequent studies have used mixed methods, especially the combination of survey and interview. One such study is “All the Best Intentions: Graduate Student Administrative Professional Development in Practice” by Karen Rowan (2009) in which she both surveyed and interviewed Graduate Student Administrators and writing center directors about their experiences with mentorship. Kate Pantelides (2010) used mixed methods as she combined a survey of writing center clients with a discourse analysis of a face-to-face writing conference about composing online discussion board posts. J. M. Dembsey’s 2017 study compared Grammarly® feedback and asynchronous online consultants’ feedback both qualitatively and quantitatively. Another mixed methods study, Perdue & Driscoll’s “Context Matters: Centering Writing Center Administrators’ Institutional Status and Scholarly Identity” (2017) examined surveys and interviews on writing center administrators’ attitudes toward research. Robert Weissbach and Ruth Pfluger (2018) conducted an experiential mixed-methods study of peer tutors working with engineering students in which they devised a tutor training program. Their data consisted of completed logs and evaluations.

2.2.4 Textual analysis is the most prevalent research method in this sample. Types of texts analyzed those related to writing centers such as publications about writing centers, session reports, artifacts from online tutoring sessions, and marketing materials such as websites. Student texts brought to the writing center are not commonly analyzed. Ligget, Jordan, and Price, who themselves analyzed writing center publications, describe text-based studies as a process of “gather[ing] a set of pertinent documents, look[ing] for and interpret[ing] selected patterns to create a new reading of the texts, and explain[ing] what the patterns contribute to disciplinary understanding” (2011, p. 66).

2.2.4.1 Publications related to writing centers. Liggett, Jordan and Price (2011) reviewed writing center literature and then revised North’s categories of research, including developing some of their own categories. Although they described their research as theoretical, it can also be classified as a textual analysis of publications related to writing centers. Driscoll and Perdue (2012) used a grounded-theory approach to analyze WCJ articles, evaluating articles for the degree to which they used RAD research. Lerner, in “The Unpromising Present of Writing Center Studies: Author and Citation Patterns in Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009” (2014) analyzed the frequency and patterns of citations of journal articles. Kathryn Valentine (2018) used content analysis to review tutor guidebooks for material on listening.

2.2.4.2 Session reports. Rita Malenczyk, in “‘I Thought I’d Put That in to Amuse You’: Tutor Reports as Organizational Narrative” (2013) analyzed the stories tutors told in their session reports through the lens of organizational theory. Laurel Raymond and Zarah Quinn (2012), both undergraduates at the time of writing, quantitatively examined tutor reports to identify students’ most common priorities for sessions and tutors’ most common concerns. Mary Hendengren and Martin Lockerd (2017) analyzed exit surveys, especially looking at negative student feedback, to assist writing centers in improving their practice.

2.2.4.3 Artifacts from online tutoring sessions. Carol Severino along with Jeffrey Swenson and Jia Zhu (2009) identified quantitative differences between feedback requests from native English speakers and non-native English speakers in asynchronous tutoring artifacts (written communication) between students and tutors. Severino and Shih-Ni Prim (2015) conducted a quantitative study of online tutor responses to Chinese students’ word choice errors. In another focus on asynchronous tutoring, Cristyn Elder (2018) analyzed thousands of emails sent to Purdue Writing Lab’s “OWL Mail” and categorized and quantified them according to the type of help they asked for.

2.2.4.4 Writing center materials. Muriel Harris, in “Making our Institutional Discourse Sticky: Suggestions for Effective Rhetoric,” studied writing center websites, brochures, and reports through a rhetorical lens. Randall Monty (2015) used Critical Discourse Analysis to examine the data of official International Writing Centers Association publications, blogs, and websites; tutor response forms; and a corpus of individual writing center websites. In his words, Monty’s goal was “to understand how writing center stakeholders create disciplinary place and space” through rhetoric and the resulting discourse (p. 33). Sherry Wynn Perdue, Diana Driscoll, and Andrew Petrykowski studied writing center job advertisements from 2004-2014 presenting quantitative results and offering suggestions for the future. Calle Àlvarez (2017) used documentary investigation to examine materials, such as articles, books, and websites, from nineteen Colombian writing centers.

2.2.5 Descriptive studies are those that focus on the kind of writing center data that North called for in 1984—data from the tutoring session, such as direct observation. Using data from tutoring sessions, Mackiewicz and Thompson (2014) described tutors’ use of politeness with tutees to enact motivational scaffolding. Sarah Nakamaru (2010) observed tutoring sessions to qualitatively and quantitatively categorize the types of lexical feedback tutors were giving. Robert Brown (2010) used discourse analysis to study representations of audiences, both real and imagined, in recorded tutoring sessions focused on personal statements for medical school applications. Yelin Zhao (2018) conducted a conversation analysis of tutoring sessions between a non-native English-speaking tutor and one non-native English speaker and a native English speaker tutee. Sam Van Horne (2012) coded student papers for revisions carried out after the conference, interviewed each consultant, and observed their writing conferences.

2.2.6 Theoretical research. Although theoretical research is not empirical and does not meet the requirements for RAD research, it is present on several research typologies, so it is included here as well. Jackie Grutsch McKinney’s “New Media Matters: Tutoring in the Late Age of Print” (2009) is a highly anthologized theoretical article about tutoring new media. Romeo Garcia’s “Unmaking Gringo Centers” (2017) is another example of theoretical research. Roberta Kjesrud and Mary Wislocki (2011) published on introspection and personal experience regarding administrative conflict. Finally, Nordlof (2014) conducted a theoretical investigation of Vygotsky and scaffolding in relation to writing center work.

2.2.7 Archival research is becoming common in composition research (Hayden, 2015; Ritter, 2012), and I predict writing center research will follow. Two articles in the data set using archival research are Lori Salem’s “Opportunity and Transformation: How Writing Centers are Positioned in the Political Landscape of Higher Education in the United States” (2014) and Stacy Nall’s “Remembering Writing Center Partnerships: Recommendations for Archival Strategies” (2014).

2.2.8 Focus groups are a useful, though underutilized, method of gathering data. One recent example of writing center research that uses focus groups is Sue Dinitz and Susanmarie Harrington’s 2014 study on tutoring sessions in history and political science to shed light on the disciplinary/generalist tutor debate. Their study included faculty focus groups and transcripts of tutoring sessions. Another example of focus group research is Tammy Conrad-Salvo and John M. Spartz’s 2012 study on the usefulness of Kurzweil text-to-speech software to students when revising papers.

2.2.9 Quasi-experiment. Experiments in the writing center context are very rare since it is difficult to control circumstances and generate random placements. Holly Ryan and Danielle Kane (2015) presented a quasi-experiment by looking at different types of classroom visits and their effectiveness. Because they used existing classes, the placement in groups was not completely random, making it quasi-experimental. Luuk Van Waes, Daphne van Weijen, and Mariëlle Leijten (2014) studied students’ use of an online writing lab (with static content) as they worked on completing an assignment through a quasi-experiment where they used a keystroke-capturing system to determine students’ writing processes. Trenia Napier, Jill Parrott, Erin Presley, and Leslie Valley (2018) used a quasi-experiment design—holistically grading research papers and comparing classes that participated to those that did not—to examine the effectiveness of their program.

2.2.10 Quantitative methods are not very common in writing center studies. Rowena Yeats, Peter Reddy, Anne Wheeler, Carl Senior, and John Murray (2010) used quantitative methods to mine data of those who had used the writing center versus those who did not. They found “a highly significant association between writing centre attendance and achievement” as well as retention (p. 499). Notably, although a dissertation and not a peer-reviewed article, D. Elton Ball (2014) used quantitative methods to measure the connection between writing center attendance and retention, which also showed positive results. In “Instruction, Cognitive Scaffolding, and Motivational Scaffolding in Writing Center Tutoring” Mackiewicz and Thompson (2014) presented a quantitative study of ten highly rated tutoring sessions and coded them for different kinds of scaffolding moves made by the tutors. They found that successful tutors used instruction more often than either kind of scaffolding.

2.2.11 Tutor research grows out of careful planning and reflection on practice. It differs from reflection and narrative in its focus on designing research from the onset. Carol Severino and Elizabeth Deifell, (2011) who have used a tutor research approach, explain that “The rationale for tutor-research is that tutors need to know as much as possible about their students as writers and learners to tutor them better; this knowledge is then communicated as research to tutors in similar situations with similar students” (p. 31). As an example, Christian Brendel (2012) carefully designed a comparative multilingual tutoring approach, practiced it with a particular tutee, and interviewed the tutee. Severino and Prim (2015) designed a project to focus on how a multilingual tutee learned and used vocabulary as well as the types of lexical errors he made. Severino and Prim collected data including interviews with stakeholders, paper drafts, written comments on drafts, tutoring logs, written observations, and a cloze (fill-in-the-blank) test. This type of research is very promising, and the field would benefit from seeing more of it in the future.

2.2.12 Narrative inquiry uses stories as the unit of analysis. Emily Isaacs and Ellen Kolba (2009) used narrative inquiry to investigate a program that placed teacher candidates into middle and secondary school writing centers. Through stories and reflections they presented their findings. This too is different from a simple “here’s what we did; here’s what happened” genre because they deliberately and thoughtfully used this method. Caraly Lassig, Lisette Dillon, and Carmel Dietzman (2013) used narrative inquiry to describe a graduate writing group.

2.2.13 Grounded theory (GT) has become a very popular research methodology in writing center studies. GT may be “a method, a technique, a methodology, a framework, a paradigm, a social process, a perspective, a meta-theory of research….GT is probably all of these at the same time” (Holton & Walsh, 2017, p. 161). Dagmar Scharold (2017) used GT in a study on cooperative tutoring, which is a kind of tutoring where there are two tutors and one tutee. So she could immerse herself in her data over a period of months, she used software (Transana) that plays the audio of interviews at the same time as the transcripts in a form of “closed captioning” (p. 40). Neal Lerner and Kyle Oddis’s study (2018) on the citation practices of WCJ authors also used grounded theory. As Lerner had looked at the actual citations in a previous study (2014), this study used surveys and interviews with authors.

2.2.14 Case study. True case studies are still rare in writing center studies. One of the only stand-alone case studies in the recent literature is Natalie DeCheck’s (2010) use of qualitative coding and semi-structured interviews to describe the relationship between one tutor/tutee pair; DeCheck was an undergraduate at the time of the study. Other case studies are often combined with another form of research. For instance, Severino and Deifell (2011) combined case study with tutor research, and Steven Corbett (2011) used case study alongside rhetorical and discourse analysis, ethnographic methods, questionnaires, interviews, and course materials.

2.2.15 Usability testing. Although usability testing is an unusual method in writing center studies, Alan Brizee and colleagues (2012) described usability testing for accessibility of the Purdue Online Writing Lab for people with blindness and low vision. Other writing center researchers could perform usability testing of writing center websites and online writing centers as well as brochures and handouts.

2.2.16 Institutional ethnography. Michelle Miley (2017) conducted an institutional ethnography of her new institution, which functioned as research and as an orientation and acculturation to her new situation. Interestingly, I found no actual published ethnographies of writing centers in my data set, although they abound in dissertations.

3: Conclusion

This review serves as an introduction to the theories and research methods current in writing center studies or at least that are finding their way to publication. Interested readers may also want to consult Theories and Methods of Writing Center Studies (Mackiewicz & Babcock, 2020). Of note in this review of published methods is the lack of teacher research, case studies, and ethnographic studies, which, in concept, would be the ideal types of writing center research. The reason for this is that writing center practitioners value story and experience. Teacher research is natural because reflective tutors do this type of research as they conduct their tutorials: trying things out, reflecting on them, refining them, re-trying, etc. Much of the research that is not actually research but presentation of narrative could be better framed as bounded case study with the simple change of getting Institutional Review Board clearance and collecting data systematically. Finally, ethnography, with an embedded researcher detailing the daily life and practices of a writing center, would provide scientific rigor along with the literary craft in the final write-up that many writing center practitioners desire.

One reviewer of this piece wanted me to express my own opinion about these research methods and theories. Although that was not my intent—my intent was to reflect what was going on in the literature but not what I thought should be going on—I can offer some thoughts. As I noted briefly above, teacher/practitioner research seems the most logical method for writing centers who employ reflective tutors and directors. Case study and ethnography also offer compelling possibilities. In the past, linguistics, discourse analysis, politeness, and analysis of talk were more prominent. However, see books and articles by Mackiewicz and others listed here in the “Descriptive” section. Taking a step back, overall, I cannot recommend specific theories or methods to researchers. The theory or method a researcher chooses will depend on their personal philosophy and outlook. John W. Creswell and J. David Creswell (2018) explained that one’s research method can and should be determined by one’s worldview, which they describe as Postpositivist, Constructivist, Transformative, or Pragmatic, each of which will be attracted by different methods. Postpositivists, who seek data and objectivity, will tend toward to quantitative measures such as surveys and experiments. Constructivists, on the other hand, recognize that different actors will have different understandings of a situation and tend toward qualitative measures such as narrative inquiry, case study, and ethnography. Transformative researchers will seek to “confront social oppression” and will tend toward action research or theories like Critical Discourse Analysis (p. 9). Finally, a researcher with a Pragmatic worldview will seek to solve problems using all the available means and may tend toward mixed methods studies and multiple theories and methods of analysis.

A better understanding of theory and research could assist writing center practitioners to get to where North wanted composition to be 30 years ago: to have a “way to frame its central problems” and a “method by which to set about trying to resolve them” (n.p.). The threads of research and theory can work together as the warp and weft of the fabric of writing center scholarship.

Notes

- Kenneth Burke was a rhetorician and scholar who popularized the idea of knowledge as an unending conversation; the parlor is where the conversation takes place. ↑

- Works in linguistic justice are also appearing. See Linguistic Justice on Campus (Schreiber, Lee, Johnson, & Fahim, 2021) which has a section on writing centers. See also several articles in issue 39.1-2 of the Writing Center Journal. ↑

References

Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. (2015). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Utah State University Press.

Aljaafreh, A., & Lantolf, J. P. (1994). Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the Zone of Proximal Development. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 465–483.

Àlvarez, G. Y. C. (2017). Perspectiva de los centros de escritura en Colombia. Hallazgos, 14 (28), 145–172.

Babcock, R. D., Dean, A., Hinsley, V., & Taft, A. (2019). Evaluating the synthesis model of tutoring across the educational spectrum.” Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, 57, 57–77. https://doi.org/10.5842/57-0-810. https://spilplus.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/810

Babcock, R. D., Manning, K., Rogers, T., Goff, C., & McCain, A. (2012). A synthesis of qualitative studies of writing center tutoring, 1983-2006. Peter Lang.

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2012). Researching the writing center. Peter Lang.

Babcock, R. D., & Thonus, T. (2018). Researching the writing center. Revised Edition. Peter Lang.

Ball, D. E. (2014). The effects of writing centers upon the engagement and retention of developmental composition students in one Missouri community college [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lindenwood University.

Bawarshi, A., & Pelkowski, S. (1999). Postcolonialism and the idea of a writing center. Writing Center Journal, 19(2), 41–58.

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberg, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. Basic.

Bibb, B. (2012). Bringing balance to the table: Comprehensive writing instruction in the tutoring session. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 92–104.

Boquet, E. (1999). “Our little secret”: A history of writing centers, pre-to-post open admissions. College Composition and Communication, 50(3), 463–482.

Boquet, E. (2002). Noise from the writing center. Utah State University Press.

Brendel, C. (2012). Tutoring between language with comparative multilingual tutoring. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 78–91.

Brizee, A., Sousa, M., & Driscoll, D. N. (2012). Writing centers and students with disabilities: The user-centered approach, participatory design, and empirical research as collaborative methodologies. Computers & Composition, 29(4), 341–366.

Bromley, Pam, Northway, Kara, Schonberg, Eliana. (2016, April 12). Transfer and dispositions in writing centers: A cross-institutional mixed-methods study. Across the Disciplines, 13(1). Retrieved from https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/bromleyetal2016.pdf

Brown, R. (2010). Representing audiences in writing center consultation: A discourse analysis. Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 72–99.

Bruffee, K. (1984a). Collaborative learning and the “Conversation of Mankind”. College English, 46(7), 635–652.

Bruffee, K. (1984b). Peer tutoring and the conversation of mankind. In G. A. Olson (Ed.), Writing Centers: Theory and Administration (pp. 3-15). NCTE.

Cahill, L., Rentscher, M., Jones, J., Simpson, D., & Chase, K. (2017). Developing core principles for tutor education. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 42(1-2), 10–17.

Carino, P. (1995). Theorizing the writing center: An uneasy task. Dialogue: A Journal for Writing Specialists, 2 (1): 23–27. Reprinted in Robert W. Barnett and Jacob S. Blumner, eds. The Longman Guide to Writing Center Theory and Practice New York: Pearson-Longman, 2008. pp. 124-138.

Carino, P. (2003). Power and authority in peer tutoring. In M. A. Pemberton & J. Kinkead (Eds.), Center Will Hold (pp. 96–113). University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt46nxnq.9

Caswell, N. I., Grutsch McKinney, J., & Jackson, R. (2016). The working lives of new writing center directors. Utah State University Press.

Coffey, K. M., Gelms, B., Johnson, C. C., & McKee, H. A. (2017). Consulting with collaborative writing teams. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 147–182.

Conrad-Salvo, T., & Spartz, J. M. (2012). Listening to revise: What a study about text-to- speech software taught us about students’ expectations for technology use in the writing center. Writing Center Journal, 32(2), 40–59.

Corbett, S. J. (2011). Using case study multi-methods to investigate close(r) collaboration: Course-based tutoring and the directive/nondirective instructional continuum. Writing Center Journal, 31(1), 55–81.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design (5th ed.). Sage.

Cromley, J. G., & Azevedo, R. (2005). What do reading tutors do? A naturalistic study of more or less experienced tutors in reading. Discourse Processes, 40, 83–113.

DeCheck, N. (2010). The power of common interest for motivating writers: A case study. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 28–38.

Dembsey, J. M. (2017). Closing the Grammarly® gaps: A study of claims and feedback from an online grammar program. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 63–100.

Denny, H. C. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one mentoring. Utah State University Press.

Devet, B. (2015). The writing center and transfer of learning: A primer for directors. Writing Center Journal, 35(1), 119–151.

Dinitz, S. (2018). Changing peer tutors’ threshold concepts about writing. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 42(7-8), 2-9.

Dinitz, S., & Harrington, S. (2014). The role of disciplinary expertise in shaping writing tutorials. Writing Center Journal, 33(2), 73–98.

Dowse, C., & van Rensburg, W. (2015). “A hundred times we learned from one another” Collaborative learning in an academic writing workshop. South African Journal of Education, 35 (1), 1–12.

Driscoll, D., & Perdue, S. W. (2012). Theory, lore, and more: An analysis of RAD research in The Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009. Writing Center Journal, 32(2), 11–39.

Ede, L. (1989). Writing as a social process: A theoretical foundation for writing centers? Writing Center Journal, 9(2), 3–13.

Elder, C. L. (2018). Dear OWL mail: Centering writers’ concerns in online tutor preparation. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 147–173.

Fitzgerald, L. (2012). Writing center scholarship: A “Big cross-disciplinary tent.” In K. Ritter & P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), Exploring composition studies: Sites, issues, and perspectives (pp. 73-88). Utah State University Press.

Fitzgerald, L., & Ianetta, M. (2016). The Oxford guide for writing tutors. Oxford University Press.

Garcia, R. (2017). Unmaking gringo centers. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 29–60.

Geller, A. E., & Denny, H. (2013). Of ladybugs, low status, and loving the job: Writing center professionals navigating their career. The Writing Center Journal, 33(1), 96–129.

Geller, A. E., Eodice, M., Condon, F., Carroll, M., & Boquet, E. H. (2007). The everyday writing center: A community of practice. Utah State University Press.

Gillespie, P., Gillam, A., Brown, L. F., & Stay, B. (Eds.). (2001). Writing center research: Extending the conversation (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604026

Greenfield, L. & Rowan, K. (2011). Writing centers and the new racism: A call for sustainable dialogue and change. Utah State University Press.

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2009). New media matters: Tutoring in the late age of print. Writing Center Journal, 29(2), 28–51.

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2013). Peripheral visions for writing centers. Utah State University Press.

Grutsch McKinney, J. (2016). Strategies for writing center research. Parlor Press.

Harris, M. (2010). Making our institutional discourse sticky: Suggestions for effective rhetoric. Writing Center Journal, 30(2), 47–71.

Hayden, W. (2015). “Gifts” of the archives: A pedagogy for undergraduate research. College Composition and Communication, 66(3), 402-426. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.utpb.edu/stable/43490936

Hendengren, M., & Lockerd, M. (2017). Tell me what you really think: Lessons from negative student feedback. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 131–145.

Hill, H. N. (2016). Tutoring for transfer: The benefits of teaching writing center tutors about transfer theory. The Writing Center Journal, 35(3), 77–102.

Hill, H. (2020). Transfer theory: A guide to transfer-focused writing center research. In J. Mackiewicz & R. D. Babcock (Eds.), Theories and methods of writing center studies (pp. 59-67). Routledge.

Hobson, E. H. (1992). Maintaining our balance: Walking the tightrope of competing epistemologies. In R. W. Barnett & J. S. Blumner (Eds.), The Longman guide to writing center theory and practice (pp. 100-109). Pearson.

Horner, W. (1929). The economy of the laboratory method. The English Journal, 18, 214–221.

Holton, J. A., & Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative & quantitative data. Sage.

Isaacs, E., & Kolba, E. (2009). Mutual benefits: Pre-service teachers and public school students in the writing center. Writing Center Journal, 29(2), 52–74.

Johanek, C. (2000). Composing research: A contextualist paradigm for rhetoric and composition. Utah State University Press.

Kastner, S. (2017). Soundbites from dialogues with Michael Spooner: A happened, happening, then retrospective on a career publishing, writing, reading, and responding. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 19–29.

Kirsch, G., & Sullivan, P. (1992). Methods and methodology in composition research. Southern Illinois University Press.

Kjesrud, R. D., & Wislocki, M. A. (2011). Learning and leading through conflicted Collaborations. Writing Center Journal, 31(2), 89–116.

Lassig, C. J., Dillon, L. H., & Diezmann, C. M. (2013). Student or scholar? Transforming identities through a research writing group. Studies in Continuing Education, 35(3), 299–314.

Lerner, N. (2006). Time warp: Historical representations of writing center directors. In C. Murphy & B. L. Stay (Eds.), The writing center director’s resource book (pp. 3–11). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lerner, N. (2007). “Seeking Knowledge about Writing Centers in Numbers, Talk, and Archives.” Writing at the Center: Proceedings of the 2004 Thomas R. Watson Conference, Louisville, Kentucky. Ed. Jo Ann Griffin, Carol Mattingly and Michele Eodice. International Writing Centers Association, 2007.

Lerner, N. (2009a). Dissertations and theses on writing centers. Writing Lab Newsletter, 33(7), 6 9.

Lerner, N. (2009b). The idea of a writing laboratory. Southern Illinois University Press.

Lerner, N. (2014). The unpromising present of writing center studies: Author and citation patterns in Writing Center Journal, 1980-2009. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 67–102.

Lerner, N., & Oddis, K. (2018). The social lives of citations: How and why Writing Center Journal authors cite sources. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 235–262.

Liggett, S. (2014). Review essay: Divergent ways of creating knowledge in writing center studies. The Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 135–151.

Liggett, S., Jordan, K., & Price, S. (2011). Mapping knowledge-making in writing center research: A taxonomy of methodologies. The Writing Center Journal, 31(2), 50–88.

Lillis, T. (2008). Ethnography as method, methodology, and “Deep Theorizing”: Closing the gap between text and context in academic writing research. Written Communication, 25(3), 353–388.

Lunsford, A. (1991). Collaboration, control, and the idea of a writing center. Writing Center Journal, 12(1), 3–11.

Mackiewicz, J., & Babcock, R. (2020). Theories and methods of writing center studies: A practical guide. Routledge.

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2013). Motivational scaffolding, politeness, and writing center tutoring. The Writing Center Journal, 33(1), 38–73.

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2014). Instruction, cognitive scaffolding, and motivational scaffolding in writing center tutoring. Composition Studies, 42(1), 54–78.

Mackiewicz, J., & Thompson, I. (2018). Talk about writing: The tutoring strategies of experienced writing center tutors 2nd Ed. Routledge.

Malenczyk, R. (2013). “I thought I’d put that in to amuse you”: Tutor reports as organizational narrative. Writing Center Journal, 33(1), 74–95.

McAndrew, D. A., & Reigstad, T. J. (2001). Tutoring writing: A practical guide for conferences. Boynton-Cook.

Miley, M. (2016). Feminist mothering: A theory/practice for writing center administration. Writing Lab Newsletter, 41(1-2), 17–24.

Miley, M. (2017). Looking up: Mapping writing center work through institutional ethnography. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 103–129.

Miley, M. (2020). Bringing feminist theory home. In J. Mackiewicz & R. D. Babcock (Eds.), Theories and methods of writing center studies (pp. 48-58). Routledge.

Monty, R. (2015). The writing center as cultural and interdisciplinary contact zone. Palgrave Pivot.

Murphy, C. (1994). The writing center and social constructionist theory. In J. A. Mullin & R. Wallace (Eds.), Intersections: Theory-practice in the writing center (pp. 161-171). NCTE.

Nakamaru, S. (2010). Lexical issues in writing center tutorials with international and US educated multilingual writers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 19(2), 95–113.

Nall, S. (2014). Remembering writing center partnerships: Recommendations for archival strategies. Writing Center Journal, 33(2), 101–121.

Napier, T., Parrott, J. M., Presley, E., & Valley, L. A. (2018). A collaborative, trilateral approach to bridging the information literacy gap in student writing. College & Research Libraries, 79(1), 120-145. Retrieved from EBSCOhost, doi:10.5860/crl.79.1.120.

Neaderhiser, S., & Wolfe, J. (2009). Between technological endorsement and resistance: The state of online writing centers. The Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 49–77.

Neuleib, J. W. (1984). Research in the writing center: What to do and where to go to become research oriented. WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, 9(4), 10–13.

Nickaly, J. (2012). Got guilt? Consultant guilt in the writing center community. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 14–27.

Nordlof, J. (2014). Vygotsky, scaffolding, and the role of theory in writing center work. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 45–64.

Nordlof, J. (2020). Vygotskyan learning theory. In J. Mackiewicz & R. D. Babcock (Eds.), Theories and methods of writing center studies (pp. 11–19). Routledge.

North, S. (1987). The making of knowledge in composition: Portrait of an emerging field. Boynton-Cook.

Nowacek, R. S., & Hughes, B. (2015). Threshold concepts in the writing center: Scaffolding the development of tutor expertise. In L. Adler-Kassner & E. Wardle (Eds.), Naming what we know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies (pp. 171-183). Utah State University Press.

Pantelides, K. (2010). Negotiating what’s at stake in informal writing in the writing center Computers & Composition, 29(4), 269–279.

Perdue, S. W., & Driscoll, D. (2017). Context matters: Centering writing center administrators’ institutional status and scholarly identity. Writing Center Journal, 36(1), 185–214.

Perdue, S. W., Driscoll, D., & Petrykowski. A. (2018). Centering institutional status and scholarly identity: An analysis of writing center administration position announcements, 2004-2014. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 265–293.

Portanova, P., Rifenburg, J. M., & Roen, D. (2017). Contemporary perspectives on cognition and writing. The WAC Clearing House and University Press of Colorado.

Pratt, M. L. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession, 1991: 33–40.

Raymond, L., & Quinn, Z. (2012). What a writer wants: Assessing fulfillment of student goals in writing center tutoring sessions. Writing Center Journal, 32(1), 64–77.

Ritter, K. (2012). To know her own history: Writing at the woman’s college, 1943-1963. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rowan, K. (2009). All the best intentions: Graduate student administrative professional development in practice. Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 11–48.

Ryan, H., & Kane, D. (2015). Evaluating the effectiveness of writing center classroom visits: An evidence-based approach. Writing Center Journal, 34(2), 145–172.

Salem, L. (2014). Opportunity and transformation: How writing centers are positioned in the political landscape of higher education in the United States. Writing Center Journal, 34(1), 15–43.

Schreiber, B. R., Lee, E., Johnson, J. T., & Fahim, N. (2021). Linguistic justice on campus: Multilingual Matters.

Scharold, D. (2017). Challenge accepted: Cooperative tutoring as an alternative to one-on-one tutoring. The Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 31–55.

Severino, C., & Deifell, E. (2011). Empowering L2 tutoring: A case study of a second language writer’s vocabulary learning. Writing Center Journal, 31(1), 25–54.

Severino, C., & Prim, S. N. (2015). Word choice errors in Chinese students’ English writing and how online writing center tutors respond to them. Writing Center Journal, 34(2), 115–143.

Severino, C., Swenson, J., & Zhu, J. (2009). A comparison of online feedback requests by non-native English speaking and native English-speaking writers. Writing Center Journal, 29(1), 106–129.

Smagorinsky, P. (2008). The method section as conceptual epicenter in constructing social science research reports. Written Communication, 25, 389–411.

Smith, F. (1987). Joining the literacy club. Heinemann.

Sunstein, B. S. (1998). Moveable feasts, liminal spaces: Writing centers and the state of in betweenness. Writing Center Journal, 18(2), 7–26.

Thompson, I. (2009). Scaffolding in the writing center: A microanalysis of an experienced tutor’s verbal and nonverbal tutoring strategies. Written Communication, 26(4), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088309342364

Threadgill, E. (2010). Writing center work bridging boundaries: An interview with Muriel Harris. Journal of Developmental Education, 34(2), 20–25.

Truesdell, T. (2007). Not Choosing Sides: Using Directive and Non-Directive Methodology in a Writing Session. Writing Lab Newsletter, 31(6), 7–11.

Valentine, K. (2018). The undercurrents of listening: A qualitative content analysis of listening in writing tutor guidebooks. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 89–115.

Valles, S. B., Babcock, R. D., & Jackson, K. K. (2017). Writing center administrators and diversity: A survey. The Peer Review, 1(1), n.p.

Van Horne, S. (2012). Characterizing successful “intervention” in the writing center conference. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 10(1), n.p. Retrieved from http://www.praxisuwc.com/van-horn-101.

Van Waes, L., van Weijen, D., & Leijten, M. (2014). Learning to write in an online writing center: The effect of learning styles on the writing process. Computers & Education, 73, 60–71.

Weissbach, R. S., & Pflueger, R. C. (2018). Collaborating with writing centers on students. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 61(2), 206–220.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Child Psychiatry, 17, 89-100. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic862383.files/Wood1976.pdf

Woolbright, M. (1993). The politics of tutoring: Feminism within the patriarchy. Writing Center Journal, 13(1), 16–31.

Yeats, R., Reddy, P., Wheeler, A., Senior, C., & Murray, J. (2010). What a difference a writing centre makes: A small scale study. Education + Training, 52(6-7), 499–507.

Zhao, Y. (2018). Student interactions with a native speaker tutor and a nonnative speaker tutor at an American writing center. Writing Center Journal, 36(2), 57–87.