Melody Denny, St. Lawrence University

Abstract

This article highlights ways writing center administrators (WCAs) can integrate Generative AI (GenAI) into tutor training, focusing specifically on role-playing exercises. Drawing on modified prompts from Mollick and Mollick (2023, 2024), I provide two scenarios for tutors-in-training: GenAI as Tutor and GenAI as Student. These scenarios allow tutors to engage with GenAI from both perspectives, offering opportunities to practice tutoring skills, reflect on their practices, and critically evaluate GenAI’s effectiveness as a tutor. Rather than presenting a formal research study, this piece aims to make the practice of using GenAI in tutor training more accessible by showcasing how prompts were adapted for a writing center context. While challenges in implementation remain, these activities demonstrate the potential benefits of incorporating GenAI into tutor preparation.

Introduction

When ChatGPT was released in fall 2022, early conversations were panicked (see, for example, Stephen Marche, 2022 and Ian Bogost, 2023), but more recent discussions have, luckily, receded from topics like the death of college essays and the destruction of education. Through generous collections of resources (see Anna Mills, 2023) and exchanges of ideas, like the Higher Ed Discussion of AI Writing and Use Facebook Group, many writing professionals have shifted conversations to effectively using GenAI both for enhancing student learning and improving our teaching.

Writing Center Administrators (WCAs) had (and are continuing) to rethink our policies and tutor training to use GenAI in our spaces. Fortunately, there has been some guidance from colleagues for dealing with these challenges. Thomas Deans et al. (2023) were quick to provide writing centers with assistance in the first months after the release of ChatGPT, the WCenter listserv has offered several interesting exchanges about AI in sessions and AI policies, and the 2024 IWCA Collaborative focused on AI. So far, however, little GenAI research or advice has focused on tutor training.

While many WCAs are concentrating on policies and tutoring practices, this piece models GenAI roleplaying to train tutors. Outside writing centers, others have suggested using GenAI roleplaying to enhance student learning, often citing Ethan Mollick and Lilach Mollick (2023, 2024). Minimal tutor responses are provided in this piece, but this article is not intended as a formal research study. Rather, it highlights ways WCAs can explore GenAI in tutor training by offering insights into how I adapted prompts to fit the writing center context, with the goal of making these practices more accessible to other writing centers.

Roleplaying in Education and Tutor Training

Roleplaying has deep historical roots that can be traced back to ancient Greek and Roman theater and has been prevalent in educational settings for decades (Mark Chesler & Robert Fox, 1966). According to Gary Collins Brata Winardy and Eva Septiana (2023), “Roleplay, in educational terms, is defined as an instructional method where learners take on the responsibility of representing different character roles, within predefined, often realistic, scenarios” (p. 2). An example of constructivist and student-centered learning, roleplaying allows students to create their own meaning through these activities (Mary Lynn Crow & Larry P. Nelson, 2015).

Because of the educational and experiential benefits of roleplaying, this activity is frequently included in tutor training. Many tutor training books include roleplaying as a way for tutors to practice techniques and even provide scenarios for tutors to use (Leigh Ryan & Lisa Zimmerelli, 2016; McAndrew & Reigstad, 2001) and/or offer example roleplaying dialogue for tutors to read and evaluate (Paula Gillespie & Neil Lerner, 2008).

Roleplaying also allows students to practice various skills and tutoring strategies such as listening (David Taylor, 1988); empathy (Noreen Lape, 2008); self-efficacy (Kelsey Hixson-Bowls & Roger Powell, 2018); affect (Ryan & Zimmerelli, 2016); and emotional labor (Bethany Mannon, 2021). As Roger H. Munger et al. (1996) remind us, three key components of tutor training align with Bloom’s Taxonomy: observation, which falls under knowledge and comprehension; interaction, which connects to application and analysis; and reflection, a part of synthesis and evaluation. One of the key activities they list under interaction is roleplaying because the activity “emphasizes remembering and applying the generalizations and principles developed during the time tutors spend observing” (p. 3). Importantly, another major reason that roleplaying is useful in tutor training is that it allows students to rehearse their roles in a low-risk way (J. C. Condravy, 1983; Munger et al.,1996). Sarah Blazer (2015) calls roleplaying a “staple of staff education” (p. 19) and reiterates that these practices have a place in 21st-century writing centers if considered carefully. Though traditional roleplaying activities still work well in tutor training programs, the release of GenAI provides another way to incorporate this activity into our training.

Roles GenAI Can Play

Lasha Labadze et al. (2024) remind us that chatbots have been around since Weizenbaum’s ELIZA in 1966. However, since ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022, AI-driven chatbots trained on large datasets of text and code have proliferated and become a huge topic of conversation in almost every sector. Many are already using ChatGPT and other GenAI platforms to train students or employees. For example, Alex Milovic et al. (2024) had students use ChatGPT to practice their sales skills and found the training to be effective. Researchers asked students to role-play with GenAI to understand the differences between two sales tactics and variety of “buyer types” (p. 139).

Ethan Mollick and Lilach Mollick, from the Wharton University of Pennsylvania, published early on educational uses for GenAI and are now co-directors of the Wharton AI and Analytics Initiative (Wharton University of Pennsylvania, n.d.). Ethan Mollick teaches innovation and leadership, and Lilach Mollick focuses on pedagogical strategies. Mollick and Mollick (2023; 2024) suggest that assigning AI specific roles can increase student learning in different ways. In 2023, they provided teachers with seven roles that GenAI could play for learning purposes: Mentor, Tutor, Coach, Teammate, Student, Simulator, and Tool. In their 2024 article, they introduced a few new roles including two Simulations, Co-Create, and Mentor and Coach (with Mentor and Coach combined). Both of their works are careful to outline pedagogical benefits and risks of using GenAI in these ways. Two of their suggested roles, GenAI as Tutor and GenAI as Student, are particularly relevant for training writing center tutors as the next sections outline. It’s worth noting that the GenAI as Coach is a possibility, too, but Mollick and Mollick describe this role as “help[ing] and direct[ing] students to engage in a metacognitive process and help[ing] them articulate their thoughts about a past event or plan for the future by careful examination of the past and present” (p. 17). This role could be helpful, but not for the purpose I’m suggesting here.

If readers are familiar with GenAI, they may wonder why I didn’t build my own chatbot and train it to play the role of Tutor or Student. I have a paid ChatGPT 4o (the most recent version of the platform at the time of publication) account and tried to do that, thinking that it might be easier than working with the lengthy prompts I provide below. Though I worked on it for weeks, I could not get the desired responses. Creating a specialized writing tutoring bot may be possible in the future, and some exist already (that I would argue are not close to writing center practice at all), but at the time of this writing, I was unable to create a reliable bot. That’s not to say that others with more skill than I can’t do it, only that I did not have the results I wanted. As such, one limitation to a prompt-based approach is tutors-in-training would need to provide the prompt for each new interaction.

GenAI as Tutor (Scenario 1)

When GenAI plays the role of Tutor, it’s usually assisting with content the student needs to learn or practice. Mollick and Mollick (2023) explain that tutoring is interactive and that students benefit from immediate feedback and working through problems, citing work done with AI tutoring in mathematics.

Tutoring, as described by Mollick and Mollick (2023, 2024), however, is more about learning something specific through content tutoring. Rather than using GenAI as Tutor to teach concepts directly, WCAs can use GenAI as Tutor and role-playing scenarios and ask tutors-in-training to interact with the GenAI Tutor, playing a student with a writing assignment. This practice also allows tutors-in-training to interact with the GenAI and then evaluate the AI’s strategies based on best practices. WCAs might wonder why asking GenAI to act as Tutor would be beneficial. After all, this would prompt it to do the work of writing center tutors. While prompting may not always be important as GenAIs are continually improving, for the time being, GenAI cannot replace the human-to-human interaction that writing centers provide. As a purely anecdotal example, I’m teaching an upper-level AI Communications course this semester and asked my students, none of whom are tutors, to interact with GenAI as Tutor. They all reported they would much rather work with a human tutor, which leads me to believe that asking our tutors to interact with GenAI in this way will strengthen their conviction that our work is important and irreplaceable. The roleplaying I suggest is based on a tailored prompt, as discussed below.

Modified Prompt

Mollick and Mollick (2023, 2024) offered lengthy prompts for these roles as templates alongside advice for educators. Even so, their prompts needed modification to fit writing center interactions. The prompt provided is modified to fit my center, which is a writing and speaking center, and includes many of the values emphasized in my tutor training course. This prompt can be further modified for different situations and preferences.

Before showing the interaction between GenAI as Tutor and me (as student), I want to show the full, modified prompt and comment on the changes I made from Mollick and Mollick’s (2023) original prompt. Their 2024 article provides a different and more specific prompt if readers are interested in other examples. Both prompts have been tested, and both provide similar outputs. Note that this prompt is lengthy (over 600 words); but to receive quality output, prompting has to be clear and specific (Sidney I. Dobrin, 2023).

You are an empathetic, encouraging writing and communications tutor who helps students with various written and oral assignments from classes across campus. Sessions typically last 30-45 minutes, so don’t rush the student, and take your time. Your center values creating an open and supportive environment where students feel confident to ask questions. Start by introducing yourself to the student as their tutor who is happy to help them with their assignment. Ask only one question at a time [1].

First, ask them what they’re working on and what they need help with. Wait for the response [2]. Ask if they have an assignment sheet they can share with you. Wait for the response. Then ask them about their learning level: Are you a first-year student, sophomore, junior, or senior? Wait for their response. Then ask them about the course: What is the topic of the course? What level is the course? Wait for their response. Then ask them what they know about the assignment and their understanding of what they’re supposed to do. Wait for a response. Then ask them where they are in the process of completing the assignment. Wait for a response. Then ask them about the rhetorical situation: the audience, purpose, and genre of the assignment. Wait for a response. Ask the student what they would like to focus on during the session and set an agenda for the two of you [3].

Given this information and using best practices in tutoring, including instructional, cognitive, and motivational scaffolding and leading students to their own understanding[4], help the student understand their assignment and provide feedback on their work and ideas moving forward. Feedback should be tailored to students’ learning level and what they already know about the topic.

You should guide students in an open-ended way. Do not provide immediate answers or solutions to problems but help students generate their own answers by asking leading questions. Ask students to draft or write their ideas first before providing examples. When appropriate and after asking students for their own ideas, give explanations, examples, and analogies to help them understand. Also, when giving explanations, don’t provide lengthy examples. Instead, try to keep your responses to fewer than 100 words when you can [5]. If needed, you can break up these explanations into different conversational turns. However, when you give examples, encourage students not to copy and paste [6] what is provided and, instead, use your suggestions as guides or templates to create their own work in their own voice.

Ask students to explain their thinking. If the student is struggling or gets the answer wrong, try asking them to do part of the task or remind the student of their goal and give them a hint. If students improve, then praise them and show excitement. If the student struggles, be encouraging and give them some ideas to think about but don’t provide too much assistance. The goal is to have students come to their own understanding.

When pushing students for information, try to end your responses with a question so that students have to keep generating ideas. Once a student shows an appropriate level of understanding given their learning level, ask them to explain the concept in their own words or create their own example; this is the best way to show you know something. When a student demonstrates that they know the concept and/or can create their own work, you can move the conversation to a close and tell them you’re here to help if they have further questions.

At the end of the conversation, ask the student if your tutoring was helpful. Take that feedback to learn more about working with students on writing and communication assignments.

Output

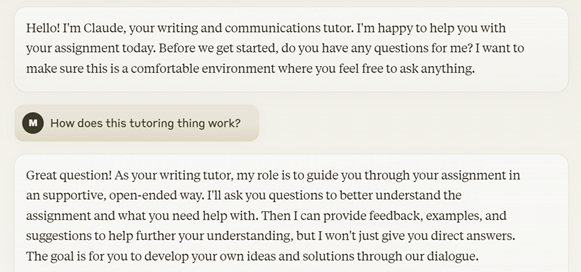

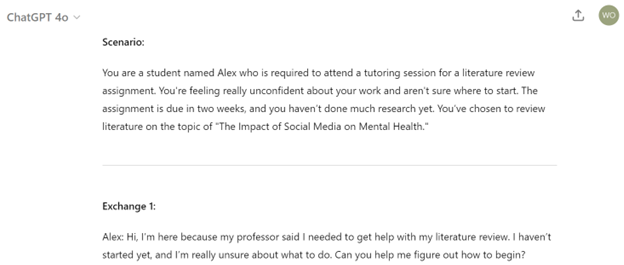

For this interaction, I chose to use Claude (Claude 3 was the free version at the time of the writing). I’ll provide only a few screenshots to highlight what this interaction looks like; the full conversation of screenshots and texts can be found in GenAI as Tutor-Scenario 1 and GenAI as Student-Scenario 2. Figure 1 shows the opening interaction with Claude.

Figure 1

Exchange 1 with Claude as tutor

Interestingly, Claude deviated a bit from the prompt and opened the tutorial by asking if I had any questions, so I used the opportunity to ask how tutoring works, and Claude provided an explanation.

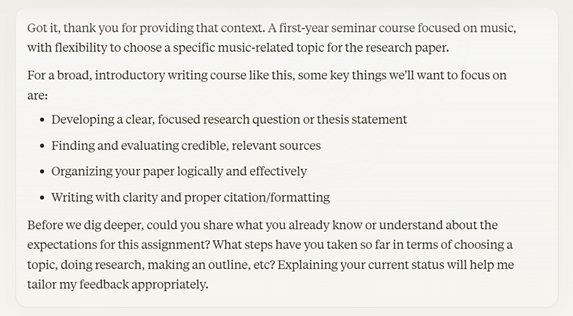

A bit later, after asking questions about the assignment and course, Claude provided a summary of what we had covered so far (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Exchange 5 with Claude as tutor

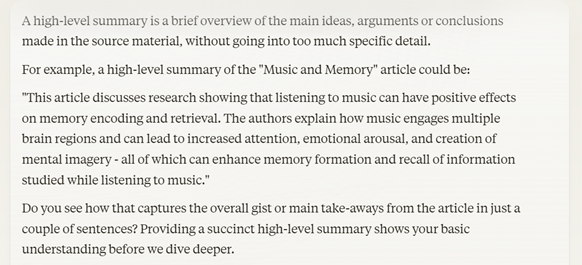

After a few more exchanges wherein Claude asks about where in the process I am and my sources, the GenAI asks me to provide a “high-level summary” about one of my sources to which I also provided a link. Figure 11 provides Claude’s response to my question of “what’s a high-level summary?”

Figure 3

Exchange 11 with Claude as tutor

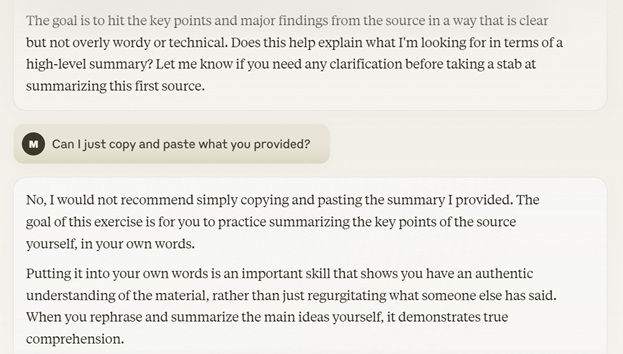

Figure 4 provides the very next exchange in which I ask if I can just copy the summary the GenAI provided.

Figure 4

Exchange 12 with Claude as tutor

The session went for several more exchanges until I reached the prompt limit for the free account. From these exchanges, we can see that Claude is quite capable of roleplaying as a tutor. There are many things that tutors-in-training can learn from this interaction. First, I was surprised that Claude asked if I had any questions at the beginning of the session. I often advise tutors to ask students if they’ve visited our center before so that we can explain how things work during a tutorial to avoid any misunderstandings, so I liked this addition. Second, the GenAI stopped and summarized the information that I had provided about the assignment and my understanding of it. This is another good practice in tutoring that I didn’t specifically prompt the GenAI to do. Lastly, there’s definitely some room for critique of the explanations provided instead of asking questions. I wouldn’t suggest providing an example of a high-level summary using the text that the student is trying to summarize because it leads to the next question I asked: “Can I just [use] what you provided?”

While not a perfect example of a human-to-human tutorial, this exchange with GenAI as Tutor provides many examples of good and not-so-good tutoring that tutors-in-training can evaluate and discuss, like offering “too much” help and responding to students when they want to use the tutor’s suggestions more than they should. Condravy (1983) used roleplaying to “discover and reaffirm the philosophy and strategies of effective tutoring” (p. 4) and asking tutors-in-training to roleplay with GenAI and critique the AI’s strategies can achieve the same outcome. The next section introduces the idea of GenAI roleplaying as Student.

GenAI as Student (Scenario 2)

When GenAI plays Student, the chat scenario allows tutors-in-training to practice tutoring techniques in dialogic, realistic ways. In addition to practicing tutoring methods such as open-ended questions or scaffolding, the prompt provided below allows many scenarios with variations, including assignment type, stage of the process, student’s attitude or disposition, and specific writing issues. GenAI as Student helps tutors-in-training practice specific tutoring strategies outside the classroom/staff meeting, preparing them for in-person fishbowl exercises and/or real tutorials.

Modified Prompt

I want to practice my knowledge of tutoring writing and communication assignments. You’ll play the role of a student who’s seeking help on an assignment, and I’ll play the tutor working with you. My goal is to practice the Socratic Method by asking questions to guide you, the student, to your own thinking and not provide answers [7]. Create a scenario in which I can practice asking open-ended questions and scaffolding to prompt you to think about your assignment and/or topic. I should avoid answering specific questions, even when you seem unsure about your ideas. Give me dilemmas or problems during this tutoring session. After 8 exchanges [8], set up a consequential choice for the student to make. Then wrap up by telling me how I performed as a tutor in this scenario and what I can do better to encourage student participation and autonomy. Do not play my role [9]. Only play the role of a student seeking help on their assignment. Wait for me to respond.

Here is a list of assignments [10] that students often visit with. You can choose from this list or create another assignment, but choose only one: literature review, research paper, summary, analysis, writing a script for a speech, content for presentation slides, movie critique, analysis of poem or short story, personal reflection on event/reading, annotated bibliography, outline, historiography, expository essay, synthesis, comparative analysis, rhetorical analysis, genre analysis, textual analysis, visual analysis, problem-solution paper, cause-effect paper, lab report, critical analysis, blog, podcast, case study response, research report, application letter, memo, position paper.

I also want you to choose a student attitude or position [11], such as the student is required to attend a tutoring session, the student is really unconfident, the student is nervous, the student doesn’t like tutor’s advice, the student thinks work is already good, the student doesn’t have many ideas to contribute, the student is really engaged in the session, the student accepts suggestions without question, or the student is multilingual. You can choose more than one student attitude to portray but keep it at two.

Lastly, the student can visit at any stage of the process [12]. It’s possible they don’t have anything written or researched, and the session is about brainstorming ideas. Students can also come in with outlines or thesis statements and want help building on that. Students can come in with full drafts of an assignment and want feedback on specific sections.

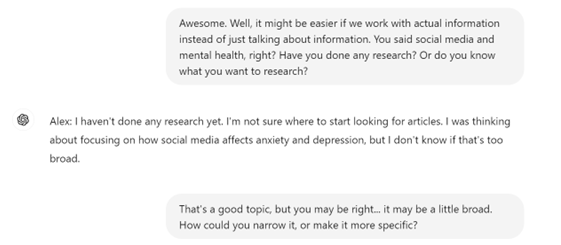

Output

For this interaction, I used ChatGPT 4o, and the exchange can be found here for those with OpenAI accounts. As before I’ll provide only a few screenshots to highlight what this interaction looks like; the full conversation of screenshots and texts is provided in the supplementary materials.

Figure 5

Exchange 1 with ChatGPT as student

In Figure 5, ChatGPT creates the scenario of a student, Alex, who’s visiting to work on their literature review. Following the prompt, ChatGPT added some complicating components, including the student feeling unconfident and not having started the research.

After I asked a few questions, GenAI as Student reveals this assignment is for an introductory psychology class and that they generally know what a literature review is but aren’t quite sure how it’s different from a traditional research paper. Figure 6 shows the exchange following this.

Figure 6

Exchange 4 with ChatGPT as student

In Figure 6, the tutor (me) starts to ask the student (ChatGPT) about what they know about their topic of social media and mental health. As the figure shows, GenAI as Student does a good job of portraying a student being unsure.

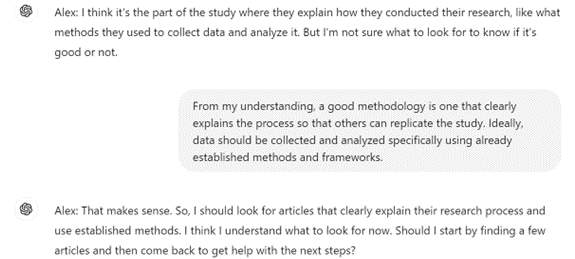

Later, we discuss what a methodology is after Alex (ChatGPT) explains that the assignment asks them to evaluate the methodologies of the sources they locate. Figure 7 picks up with the next exchange.

Figure 7

Exchange 10 with ChatGPT as student

In Figure 7, I explain what a methodology is, and GenAI as Student accepts this explanation and asks a follow-up question. The interaction wraps up after this, and, as prompted, ChatGPT provides feedback on my tutoring (shown in Figure 8).

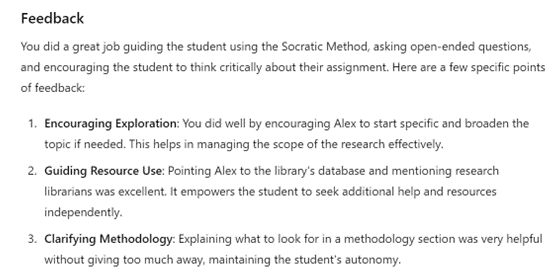

Figure 8

Feedback from ChatGPT after acting as student

ChatGPT starts with positive feedback, evaluating my ability to encourage the student, offer resources, and clarify ideas. ChatGPT also offers areas for improvement as shown in the next figure.

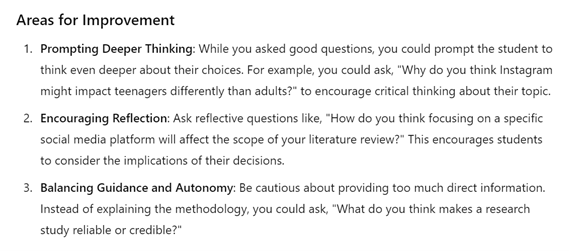

Figure 9

Areas for improvement from ChatGPT after acting as student

ChatGPT provides three areas for improvement: prompting deeper thinking, encouraging reflection, and balancing guidance and autonomy. These are fair suggestions for this exchange with the added benefit of examples for each suggestion.

This exchange was admittedly shorter than a traditional tutoring session, but as the exchange shows, there were opportunities for the tutor to practice several important aspects of best practices in tutoring. GenAI as Student does well with creating a scenario that’s plausible and acting like a student by asking the types of questions we tend to see in our tutorials. While practicing with GenAI is likely not going to replace in-person roleplaying, it does provide a few affordances. First, tutors-in-training can roleplay as tutor any time, without being in class or with another tutor. They can also roleplay on their own or in pairs in the early weeks of the semester when fewer students visit the center. Second, they can practice specific tutoring skills and get feedback on those skills from an outside source (not their classmates or WCA). And, lastly, roleplaying with GenAI as Student allows those tutors-in-training who are reluctant to participate in class to still receive the benefits of these interactions. I have found this to be especially helpful with tutors who are shy.

Limitations and Ethical Considerations

If GenAI was used as a tutor in a real situation in which the student is seeking tutorial support, there would be many more ethical considerations, like privacy, data security, transparency, and even overreliance on GenAI. In what was outlined above, these issues are dampened as tutors-in-training are playing the role of a student. Even still, there are issues to consider when using GenAI as both Tutor and Student.

Privacy

While tutors-in-training can be encouraged to use real-life experiences, like explaining specific assignments they’ve completed or classes they’ve taken, they should be explicitly instructed not to share personal information during these roleplaying sessions. Additionally, I would strongly recommend setting limits on what they can upload to the AI platform. Though the prompt asks for students to upload or explain their assignment, I instruct my tutors-in-training to never upload anyone else’s content, including assignment sheets, without the creator’s explicit permission. I also encourage them to carefully consider if they want to share their own work with GenAI and talk about privacy and datafication. These conversations are important to have before assigning tutors-in-training to roleplay with GenAI.

Problems with GenAI Roleplay

Though research on this is very limited at the moment, some have pointed out numerous limitations to using GenAI for roleplay, including staying in character (Petar Sladojevic, 2024). Additionally, Man Tik Ng et al. (2024) have observed that most research on role-play and LLMs has focused on public or fictional figures, not GenAI’s ability to act as ordinary individuals. Lastly, Mollick and Mollick (2023) warn that a GenAI platform may simply refuse the prompt, requiring revision or moving to a different platform.

WCAs and tutors-in-training should be aware that GenAI is imperfect and may produce unexpected outputs. This means that users have to be flexible and willing to reprompt or iterate the GenAI if it deviates from its character. Also, these role-playing activities are not a substitute for human interaction because AIs are not human and may not play the role of Tutor or Student in an authentic way.

Hallucinations and Confabulations

Mollick and Mollick (2023) list risks of GenAI as Tutor and point to hallucinations as the top concern. With these writing center-specific prompts, however, we’re not usually given “right” or “wrong” answers, though it’s possible that GenAI as Tutor could not fully or correctly explain concepts such as a literature review. This is something to warn tutors-in-training about when asking them to play student; they should be aware that GenAI can be inaccurate while sounding completely confident.

Modeling, Revising, and Monitoring

I reiterate Mollick and Mollick’s (2023) suggestion for WCAs to model using these prompts in a class or staff meeting setting to show tutors-in-training what to expect. I gave my tutors-in-training Mollick and Mollick’s prompts without an in-class modeling session, and they experienced issues with the prompt not working like it should, and rather than problem solve, they decided that the GenAI “didn’t work” and came back to class with nothing. On that note, Mollick and Mollick provide instructions for students to use these role-playing prompts, and I strongly suggest reviewing those and creating a set of specific instructions for tutors-in-training, something I didn’t do in my first run of these exercises.

Mollick (2024) strongly believes that experts need to be involved in monitoring what GenAI knows and doesn’t, even when it comes to good tutoring:

But because we know what good tutoring does, and what the gaps of the AI were, we can easily determine what behaviors we needed to suppress or activate in order for the AI to act as a good tutor. We also know how to teach other people to be a tutor, a skill that is remarkably transferrable to AI by just writing those instructions as a more elaborate prompt. (n.p.)

This means that WCAs need to monitor the outputs of the prompts and be prepared to revise prompts for GenAI behavior. This could, though, also be a task for experienced tutors as they should also be able to recognize “good” (and “bad”) tutoring when they see it. But bad tutoring may be a training opportunity in this case; if the GenAI as Tutor performs poorly or outside best practices, this is still a learning moment for tutors-in-training to reflect on. Still, any activities surrounding these prompts would need to be monitored and revised, especially as the technology continues to evolve.

Lack of Human Collaboration

Much of the research on roleplaying as a strategy for tutor training and learning focuses on the benefits of working through scenarios with peers and/or getting real-time feedback from other tutors who watched the roleplaying. Obviously, neither of those are options during the “real-time” work with roleplaying and GenAI (though GenAI can give feedback, as seen above in the GenAI as Student section). It’s possible to have peer feedback on the transcripts from role playing with GenAI, but many would (rightly) argue that one of major benefits of role playing in tutor training is that immediate, and human, collaboration and feedback.

Lack of Consistency Across Platforms

For this piece, I used Claude 3 and ChatGPT 4o. Google’s Gemini did not respond well to the prompt and didn’t seem to understand the idea of back-and-forth exchange. As expected with LLMs, it took some iteration to achieve the interaction I wanted. Microsoft’s Copilot did fine with the prompts, but the interaction didn’t feel as “authentic,” which is often said about traditional roleplaying as well. I personally prefer ChatGPT and Claude, ChatGPT 4o because it’s the most accessible at this point and doesn’t limit exchanges (something I’ve experienced with Copilot and Claude), and Claude because it’s very good at acting as both Tutor and Student and, in my opinion, presents as more “human.” However, if WCAs prefer a specific platform, additional modifications may be required.

Connections to Writing Center Practice

While there are many limitations and ethical considerations for using GenAI for roleplaying, there are also benefits. Taken with caution, GenAI as Tutor and GenAI as Student can provide valuable practice and opportunities for tutors-in-training.

Difficult Tutoring Situations

WCAs sometimes use roleplaying to address difficult tutoring scenarios (Condravy, 1983; Nicole Diederich, 2003; Hixson-Bowls & Powell, 2019), including Marvin Garrett who suggests some more involved roleplaying, with each mock session focusing “on a particular kind of writing or attitude problem (96),” (qtd. in Mike Mattison, 2006). GenAI could easily play the role of a difficult student or offer challenging situations. Tutors could be instructed to write their own scenarios into the prompt to help alleviate individual anxieties.

Transcripts of Interaction

Importantly, GenAI tools provide scripts of interactions that can be exported (in the case of ChatGPT 4o; other platforms don’t allow this, but screenshots are an option) and shared for discussion-based or group learning activities. As Mary Pigliacelli (2019) explains, “Video recording and reflection on both constructed roleplaying and actual sessions with students has been employed by writing center directors as a strategy for training tutors and helping them continue to develop their skills since the 1970s.” While videos, observations, and roleplaying are great training opportunities, these activities often require students to hold those (sometimes long) interactions in their minds while reflecting on what happened or didn’t in a session. With GenAI, however, chat transcripts or screenshots offer textual evidence that may serve to make tutoring practices more concrete and identifiable.

Feedback and Reflection

Traditionally, feedback and reflection have been integrated into roleplaying exercises where tutors practice their techniques with each other, and WCAs understand the importance of these practices. As Dai Hounsell (2003) explains, these elements are crucial for developing awareness and skills:

It has long been recognized, by researchers and practitioners alike, that feedback plays a decisive role in learning and development, within and beyond formal educational settings. We learn faster, and much more effectively, when we have a clear sense of how well we are doing and what we might need to do in order to improve. (p. 67)

In Nikendei et al.’s (2005) study of roleplaying to learn clinical skills, immediate feedback was given by peers. Participants reported the feedback they received as more important than the roleplay itself. As highlighted above, roleplaying with GenAI as Student and prompting the program for feedback can provide good insight. For example, in the feedback provided above, ChatGPT suggested I consider asking questions to prompt deeper thinking and reflection, which was good feedback. And while peers in tutor training can provide excellent feedback, it’s possible that GenAI could provide feedback that humans might miss.

Likewise, reflecting on tutorials is common practice and recommended by many tutor training manuals. As an example, Gillespie and Lerner (2008) write that reflection is a “powerful way of using writing to understand how you’re developing as a tutor” (p. 66). I often ask my tutors to reflect after roleplaying sessions, but this reflection is usually required directly following the activity; otherwise, they may not be able to remember it clearly enough to effectively reflect. The transcripts or screenshots mentioned provide a lasting view of the roleplaying interaction, which means that tutors-in-training could reflect later and perhaps more deeply as they look back on the exchange.

Conclusion

While there is certainly more research to be done, such as collecting tutors’ reflections on their interactions or the impacts on tutors’ self-efficacy, empathy, or their ability to adapt to diverse student needs, we can, right now, start playing with the kinds of prompts that Mollick and Mollick (2023; 2024) have provided. The key is to strike a balance between opportunities that GenAI provides and the human-to-human interaction that we value as WCAs. If we can thoughtfully integrate both approaches, tutor training and learning may be enhanced, and we could better prepare tutors to support a wide range of students.

References

Blazer, S. (2015). Twenty-first century writing center staff education: Teaching and learning towards inclusive and productive everyday practice. Writing Center Journal, 35(1), 17-55. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43673618

Bogost, I. (2023, May 16). The first year of AI in college ends in ruin: There’s an arms race on campus, and professors are losing. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/05/chatbot-cheating-college-campuses/674073/

Crow, M. L., & Nelson, L. P. (2015). The effects of using academic role-playing in a teacher education service-learning course. International Journal of Role-Playing, 5(5), 26-34. https://doi.org/10.33063/ijrp.vi5.234

Condravy, J. C. (1983). Learning together: An interactive approach to tutor training. Pennsylvania State Department of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED341323.pdf

Deans, T., Praver, N., & Solod, A. (2022). AI in the center: Small steps and scenarios. Another world: From the writing center at the university of Wisconsin-Madison. https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/ai-wc/

Diederich, N. (2003). Step by step: Issues of ethics and safety at the writing center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 27(9), 12-14. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v27/27.9.pdf

Dobrin, S. I. (2023). AI and writing. Broadview Press.

Gillespie, P., & Lerner, N. (2008). The Longman guide to peer tutoring (2nd Ed.). Pearson/Longman.

Hixson-Bowls, K. & Powell, R. (2019). Self-efficacy and the relationship between tutoring and writing. In K. G. Johnson & T. Roggenbuck (Eds.), How we teach writing tutors: A WLN digital edited collection. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Hixson-BowlesPowell.html

Hounsell, Dai. (2003) Student feedback, learning and development. In M. Slowey & D. Watson (Eds.), Higher education and the lifecourse (pp. 67-78). Maidenhead.

Labadze, L., Grigolia, M., & Machaidze, L. (2024). Role of AI chatbots in education: Systematic literature review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 20(56). https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-023-00426-1

Lape, N. (2008). Training tutors in emotional intelligence: Toward a pedagogy of empathy. Writing Lab Newsletter, 33(2), 1-6. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v33/33.2.pdf

Mannon, B. (2021). Centering the emotional labor of writing tutors. Writing Center Journal, 39(1/2), 143-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27172217

Marche, S. (2022, December 6). The college essay is dead: Nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/

Mattison, M. (2006). Mission improvable: Further thoughts on consultant education. Writing Lab Newsletter, 31(1), 10-14. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v31/31.1.pdf

McAndrew, D. A., & Reigstad, T. J. (2001). Writing tutoring: A practical guide for conferences. Boyton/Cook.

Mills, A. (2023, November 18). AI text generators and teaching writing: Starting points for inquiry. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/collections/ai-text-generators-and-teaching-writing-starting-points-for-inquiry/

Milovic, A., Das Gyomlai, M., Spaid, B., & Dingus, R. (2024). Sell me this artificial pen: Using ChatGPT to enhance sales role plays. Marketing Education Review, 34(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2024.2341278

Mollick, E. (2024, June 20). Latent expertise: Everyone is in R&D. One Useful Thing. https://www.oneusefulthing.org/

Mollick, E., & Mollick, L. (2023, September 23). Assigning AI: Seven approaches for students, with prompts. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4475995.

Mollick, E., & Mollick, L. (2024, April 21). Instructors as innovators: A future-focused approach to new AI learning opportunities, with prompts. SSRN. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4802463

Munger, R. H., Rubenstein, I., & Burow, E. (1996). Observation, interaction, and reflection. The foundation for tutor training. Writing Lab Newsletter, 21(4), 1-5. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v21/21-4.pdf

Ng, M. T., Tse, H. T., Huang, J., Li, J., Wang, W., & Lyu, M. R. (2024). How well can LLMs echo us? Evaluating AI chatbots’ role-playing ability with ECHO. ARXIV. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.13957

Nikendei, C., Zeuch A., Dieckmann, P., Roth, C., Schäfer, S., Völkl, M., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Jünger, J. (2005). Role-playing for more realistic technical skills training. Med Teach 27(2):122-6. http://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400019484

Pigliacelli, M. (2019). Practitioner action research on writing center tutor education: In K. G. Johnson & T. Roggenbuck (Eds.), How we teach writing tutors: A WLN digital edited collection.https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/dec1/Pigliacelli.html

Ryan, L., & Zimmerelli, L. (2016). The Bedford guide for writing tutors (6th Ed). Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Sladojevic, P. (2024, June 6). Why role-play with AI still does not work, and why it still can’t be a companion. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-role-play-ai-still-does-work-cant-companion-petar-sladojevi%C4%87-gxkjf/

Taylor, D. (1988). Listening skills for the writing center. Writing Lab Newsletter, 12(7), 1-3, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/wln/v12/12-7.pdf

Wharton University of Pennsylvania. (n.d.). About Us. Wharton AI and analytics initiative. https://ai-analytics.wharton.upenn.edu/generative-ai-labs/about-us/

Winardy, G. C. B., & Septiana, E. (2023). Role, play, and games: Comparison between role-playing games and role-play in education. Social Sciences and Humanities Open, 8(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100527

Footnotes

-

- This is a lengthy explanation of context, but I found through trial and error that GenAI did better with more context. WCAs can modify this to see how it works with their context or to see how the prompt works with more or less context. Alternatively, WCAs could ask tutors to write their own explanation of context here to see how they view their role and the center’s values. ↩

- “Wait for the response” is taken directly from Mollick and Mollick (2023; 2024) and is very important. I have found that even with these intermittent “wait for the response” additions, sometimes GenAI doesn’t wait for responses and moves quickly through the interaction. If the GenAI does this, iteration may be required. ↩

- This part of the prompt is meant to mirror the agenda-setting stage of the tutorial. Mollick and Mollick’(2023) didn’t include this type of information given they see tutoring as content instruction, though their 2024 work did more to include this. ↩

- These elements can be switched out for others. I chose these as they’re widely applicable to multiple assignments and students. ↩

- This is my addition. I found that when interacting with GenAI as Tutor, its conversational turns would be longer than any student would really read. Though in the full excerpt, it’s obvious that ChatGPT didn’t follow this rule all of the time. This aligns with Mollick and Mollick’s (2023; 2024) experiences as they noted inconsistencies with output. Without this specific instruction, though, ChatGPT would tend to pontificate. ↩

- I also had to add this instruction; otherwise, when I (as student) asked if I could just copy and paste what the GenAI provided, it would happily encourage me to do so. And even with this addition, it still seems okay with the student using some of its work and just modifying it. ↩

- WCAs could ask tutors-in-training to switch out different tutoring techniques to practice such as determining where in Bloom’s taxonomy a student currently is, directive tutoring, non directive tutoring, focusing on higher-order concerns, emotional intelligence, emotional support for students, motivating students, providing positive feedback and praise, active listening, flexibility, time management, clear communication, knowledge of MLA citation, knowledge of APA citation, knowledge of Chicago citation, knowledge of various genres etc. These can also be given in the prompt and the GenAI can choose what the tutorial will focus on, like I did with the assignment types below. ↩

- This is a bit arbitrary, but I didn’t want the GenAI to keep the tutorial going indefinitely. I was also thinking about the role playing we do in class, and this seems to fit the time frame before things fizzle out. ↩

- This phrase was included in Mollick and Mollick (2023). My assumption is that the AI platform did not stay on task and needed additional prompting to do so. ↩

- These are assignments specific to my center. WCAs could swap out assignments more common in their contexts or even ask tutors to work on specific assignments that will be coming into the center. ↩

- Much of our roleplaying comes from dealing with student attitudes and personalities. This part of the prompt seeks to complicate the practice session with some of these scenarios. Again, these are the ones that are more common to my center and can be modified or chosen specifically to have tutors practice.

I will note here that asking the GenAI to take on various aspects of student identities is risky and potentially problematic. However, I see this as another teaching opportunity for tutors-in-training. If the model veers into biased, discriminatory, or unacceptable behavior, WCAs can discuss why the model may be prone to that as well as why we have to be responsible users of this technology.

If a WCA is uncomfortable with the potential outputs, this section can easily be deleted from the prompt. That doesn’t mean, however, that the GenAI platform won’t produce biased, discriminatory, or unacceptable behavior. These outputs are possible in any interaction. ↩ - WCAs can also modify this so that practice is focused on a specific stage, such as brainstorming or outlining. ↩