Patricia Haney, DePaul University

Abstract

As a writing center community, we are constantly striving for ways to address underrepresentation to help restore justice in our centers. In this article, I discuss how the current makeup of writing center administrators does not reflect the U.S. student population. As a response to this historic underrepresentation in writing center administration, I propose that we utilize structures from mentorship theory to develop actionable ways to bring diverse student voices to the forefront of writing center leadership. These methods for increased representation include tutor-led Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, Time-bound (SMART) projects, tutors serving as professional development facilitators, and rap sessions. Ultimately, this article should serve as a guided starting point to help writing center administrators to continually critique and reflect on how they represent the voices of the student populations they serve.

Keywords: administrative underrepresentation, peer mentorship, professional development, student diversity, writing center leadership

Introduction

As a biracial, proud-as-hell lesbian, I have often entered academic and professional contexts hesitantly. When thinking about how my identities show up in my academic and professional work, I routinely feel resistant towards strict conventions, similar to Gloria E. Anzaldúa (1987) when she famously writes, “Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out” (p. 34). That is exactly how I have felt for much of my college career—like I would prefer physical, bodily sacrifice over surrendering my identities to the institution. However, as Anthony Paré (2002) mentions in his study on complex relationships to genre and hierarchy, “Resistance or subversion is not always easy or possible, especially for the student [or] the new practitioner” (p. 69). Despite strong feelings of resistance towards academic constraints, I have submerged myself in conventions time and time again to keep my head above water as an aspiring scholar at my predominately white institution.

However, since my first day of work orientation, I sensed that DePaul’s University Center for Writing-based Learning (the UCWbL) was different from other academic and professional settings I had faced in the past. The UCWbL’s recruitment tag line encouraged applications from “nice people, good writers,” and I found that to be true upon my very first day. Despite only knowing two of the almost 100 people at our all-staff orientation, I didn’t feel alone because of the immediate peer mentorship and sense of community. Now, I work as a tutor, receptionist, and Head. As a Head, I collaborate with three other student leaders to manage day-to-day operations for our 100-person staff. This kind of student leadership has been an essential element of the continued comfort I feel amongst the UCWbL community.

Although the writing center where I work is comprised of mostly white and heterosexual staff members (reflective of my school’s population), I have felt free to voice my unique perspectives due to representation in our student leadership. Throughout my time at the UCWbL, other peer tutors and student leaders with identities both like and different from mine have not only allowed me to participate in difficult discussions but emboldened me to as well. This experience of being able to safely communicate my perspectives continued through my promotion to Head. Upon starting my new responsibilities, I communicated with my center’s administrators and coordinators much more frequently. I not only sat in on but was a part of operations meetings where we discussed policies and procedures. I worked with the other Heads on developing professional development requirements for tutors. Suddenly, my biracial, queer voice was amplified—the novelty of this experience was intimidating. However, it was my relationships with other student leaders that helped me feel confident about my own leadership as genuine and authentic representation of my identities within the UCWbL and DePaul’s larger university community.

Through my position as a Head, I have directly experienced the importance of student leadership in writing centers. Focusing on reflection and inquiry, throughout this article I will further probe why we should continue to discuss the role of student leadership in writing center work. The major themes I will touch on are the lack of representation in writing center administration and the significance of peer mentorship. From my experiences, having strong connections with peer mentors has helped me feel comfortable and safe discussing issues of diversity with our administrators as a student leader. Additionally, peer mentorship is an important step towards solidifying long-lasting and authentic representation in the writing center world. Finally, I will provide actionable next steps for writing center administrators to consider when working towards diverse representation in their centers.

Diversity and Representation

In October 2019, I attended the International Writing Center Association’s annual conference in Columbus, Ohio. Since this was my first genuine exposure to the professional world of higher education, I have reflected on the conference a lot — and how damn white it was. I am used to being the only person who looks like me in educational and professional settings; however, as I researched writing center inclusivity and diversity practices in preparation for my collaborative presentation at the conference, I expected that writing center administrators would be more reflective of the student populations they oversee. From my early academic research on writing centers, it was clear to me that there is a strong, communal dedication to building equity in writing center spaces. I anticipated writing centers might champion this dedication by hiring diverse leaders. However, I now know it’s never that simple.

For this article specifically, I have probed further into research on the diversity of writing center administrators. In their article “Writing Center Administrators and Diversity: A Survey,” Valles et al. (2017) share their findings from a survey exploring the diversity of writing center administrators through multiple identifiers including race, gender, level of education, language, and disability. For more than a decade, Valles et al. worked on this project because of the writing center field’s focus on student diversity and the lack of research on administrator diversity. Through their survey emailed to 1,466 unique email addresses, Valles et al. (2017) found that writing center administrators are largely white (91.3%) and do not identify as LGBT (93.5%). However, the United States Census Bureau reported that in 2017, only 79% of college students identified as “white alone,” and the Postsecondary National Policy Institute reports that of a survey of 33,000 college students, 10% identified as LBGTQ (United States Census Bureau, 2018; Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2018). Although not surprising due to my anecdotal experience, learning these statistics further motivated me to question our current situation. While the U.S. Census Bureau and the Postsecondary National Policy Institute data collections don’t focus on writing center work in the way Valles et al. do, these numbers show that, on a larger scale, the identities of writing center administrators do not reflect the U.S. student population at large.

Regarding diversity in writing center staff, Denny (2010) discusses the importance of not only being multicultural but moving beyond demographics alone to engage in genuine and meaningful representation. He states:

Being multiracial (or inclusive in any number of ways) doesn’t get into how race (or any other identity intrinsic to who we are) gets played out or acted on in everyday practice . . . Having diversity isn’t enough or a necessary end; instead, we need to process whether and how it happens and to what consequence. (p. 38)

Looking at the numbers and considering Denny’s attitudes, I think it’s safe to say we’re not all going to wake up one morning to Blacker, queerer, more diverse writing center administrations. And, even if we did, increased diversity amongst administrators may not fully address problems relating to the lack of representation in our administrative processes and decision making. As we consider ways to implement the dedication to equity that drew me into writing center work in the first place, we must ask: how do we move beyond the appearance of diversity to create authentic representation in our centers?

Because our administrations cannot (and maybe shouldn’t) change overnight, it is important to consider what we can do right now to enact authentic representation in our administrative spaces. In most cases, administrators are not even the ones bringing diversity to our academic tables, students are—and they don’t just provide racial and LGBTQ representation. Students working as tutors also provide diverse experiences pertaining to socioeconomic status, levels of education, and languages spoken. Student leaders today could very well be inspired to engage with writing center work long-term and provide more diverse, meaningful professional representation in our field to future generations of tutors and student bodies. The leadership experiences I’ve had as an undergraduate student have inspired me to consider pursuing writing center studies as a professional, long-term goal. However, my feelings of security in a writing center career are contingent on a global change towards greater representation in writing center administrative work. Even though someone with my identities pursuing writing center studies professionally is an important step towards representation, folks like me cannot make this global change alone.

Peer Mentorship

One of the most emphasized roles in the writing center community is that of the peer: more specifically, the peer relationship between tutor and writer. North (1984) explores this relationship in “The Idea of a Writing Center” as he states, “In short, we are not here to serve, supplement, back up, complement, reinforce, or otherwise be defined by any external curriculum. We are here to talk to the writer” (p. 440). Tutors are writing mentors whose jobs are not to instruct writing but to support writing as a process—tutors do not necessarily serve the institution but rather their peers. It is this peer relationship that writing centers rely on to conduct authentic and productive appointments.

Because of the writing center field’s emphasis on the peer relationship between tutor and writer, I often find myself wishing there was more discussion surrounding peer mentorship, not just with those outside the tutoring role, but within it as well. From my experiences as an undergraduate tutor, there seems to be a lack of professional conversations surrounding internal peer relationships in our field. Do we value professional peer mentorship between tutors to the same degree that we value educational peer mentorship between tutors and writers? From experience, peer support has been critical to my professional and personal development. As a new tutor, I was naturally intimidated by my writing center’s administrators and coordinators, especially since my previous work experiences enforced a much more rigid workplace hierarchy. Being able to approach and learn from veteran tutors and student leaders within our workplace gave me the confidence to take on a sense of leadership in my work.

A personal experience with peer mentorship that is particularly memorable came from my first week working at the writing center. As a part of my mandatory training, I interviewed two returning tutors to learn about their approaches to writing center work. One of my mentors told me something along the lines of, “You will never be an expert tutor. There is always something new to learn.” This advice was foundational for me as I’ve grown into my identities as a tutor and hopeful writing center researcher. This advice helped me put my role into perspective—although I may sometimes impart knowledge onto writers with whom I work, I am always participating as a learner as well.

Turns out, the positive mentorship I’ve received from my writing center peers is backed up by the research and the application of mentorship theories. For starters, peer mentoring can be defined is as “a process where there is a mutual involvement in encouraging and enhancing learning and development between two peers” (McDougall & Beattie, 1997, as cited in McManus & Russell, 2007, p. 278). This definition, in particular, resonates with me because of its emphasis on mutuality and knowledge exchange. In the same way that tutors often learn from the writers with whom they work, peers in mentoring relationships learn and develop together. More specifically, in their research on various models of peer mentorship, McManus and Russell (2007) focus on collegiate peer mentorship. They write, “The main functions of the collegiate peer are career strategizing, job-related feedback, and friendship. Information is shared, and there are increasing levels of self-disclosure and trust” (p. 277). Peer-mentor relationships in higher education have the potential to strive beyond strictly professional or educational development. Instead, these relationships have the opportunity to foster a greater sense of community and, in turn, genuine personal development.

Beyond the collegiate peer mentor’s ability to increase self-disclosure and trust, Campbell et al. (2012) explore how these mentorship relationships can work to facilitate leadership as well. Their research focuses especially on the relationship between peer mentorship and student leadership capacity. Among the college students who participated in their study, they concluded that “Students who scored higher on the scale indicating that their mentor had helped them to develop personally . . . tended to have higher socially responsible leadership capacities” (p. 614). In other words, by promoting personal development in peer-mentor relationships, they found that student mentees overall had a higher capacity for socially responsible leadership. Socially responsible leadership capacity was measured using a Socially Responsible Leadership Scale which tests for things such as “consciousness of self, congruence, commitment, collaboration, common purpose, controversy with civility, citizenship, and change” (p. 605). This kind of leadership capacity is essential to the goals of long-lasting representation because it helps mentors and mentees engage with values such as self-awareness, collaboration, and change. These values can help promote and create spaces for conversations that address problems of diversity as well as solutions for these problems.

Introducing and encouraging collegiate peer mentorship in writing centers not only provides a sense of community among tutors, but it can also help tutors further develop their leadership skills. These leadership skills and experiences are essential for the greater purpose of increasing authentic representation in writing center spaces. By producing student leaders through peer mentorship, writing center administrators can increasingly rely on these student leaders to provide meaningful and critical feedback on operations such as writing center policies and procedures. As previously mentioned, it is common that most writing center diversity comes from student employees. This means that decisions made by administrators alone do not always include all the voices of those affected by such decisions. By encouraging socially responsible leadership through peer-mentor relationships, we can create increased opportunities for the diverse voices of tutors to be included in writing center leadership actions. In the following section, I will expand on actionable next steps writing center administrators can utilize to highlight the voices of their diverse student leaders in a way that is genuine and honors folks’ everyday experiences.

Actionable Next Steps

As Barron and Grimm (2002) state, “it’s far easier to theorize about diversity in a scholarly article or conference paper than to meaningfully instantiate productive diversity in a writing center program” (p. 60). So, what’s next? At my institution, our Vincentian mission asks, “What must be done?” However, I’d like to pose—more specifically—what must we do? How do writing center administrators and leaders create authentic representation within their centers? How do we move from idealistic altruism to actionable policy?

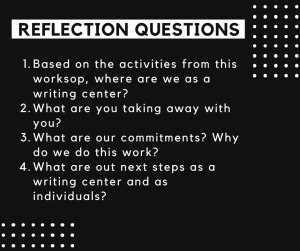

Three methods I propose are student-led SMART projects, professional development facilitators, and rap sessions for policy changes and administrative decisions when deemed appropriate. These are approaches I have experienced in my own writing center work which have led me to believe in their utility—the first-hand experience of being heard in these ways has been invaluable to my professional and personal development and the development of the UCWbL.

SMART projects

The first actionable step I propose is SMART projects led by tutors themselves. Goals and projects following SMART criteria were popularized from an article by George T. Doran in Management Review. The original article defined SMART as Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic, and Time-related (Doran, 1981). Since Doran’s article, folks in professional and educational fields have used various combinations of words to define SMART criteria. For this article, I will use the following:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Attainable

- Realistic

- Time-bound

The purpose of grounding project-based work in SMART criteria is to help guide participants to ensure their project goals are accomplished. I suggest that administrators post a call for proposals encouraging SMART projects led by tutors.

Admittedly, tutor-led projects may be more efficient or accessible for centers with larger staff and more down-time. However, I believe a handful of spare moments scattered throughout an academic quarter or semester can be used efficiently to complete such projects. The main purpose of encouraging proposals for tutor-led SMART projects is to allow student employees to bring their concerns, ideas, and creativity to the forefront of writing center administrative work. While writing center administrators put in incredible work to ensure our centers operate smoothly, we must not forget that tutors are the ones who do writing center work every day. Tutors conduct appointments, communicate with institution faculty and staff, and do writing center outreach maybe without even knowing it. Because of tutors’ direct involvement in the day-to-day hustle of writing center operations, their ideas for projects to better the writing center should not only be welcomed but encouraged as a necessary step to representing diverse voices in the work we do.

So, how can writing center administrators support tutor-led projects? For starters, administrators can put out a formal call for proposals. Formalizing this encouragement for projects will further validate the center’s desire for student leadership, peer collaboration, and increased representation. Additionally, while discussing project proposals, administrators can offer as much or as little support needed for tutors to complete their projects. I acknowledge that all administrators may not have as much time as they desire to work with tutors in this capacity, but I encourage administrators to consider how an initial time investment in a project to this degree can pay off long term. In this model, administrators serve as mentors with certain expertise in writing centers and writing center studies while also displaying trust by acknowledging the tutor’s abilities to take the lead on the project they propose. Finally, it is important to discuss how the project meets the SMART criteria to ensure structure and accountability for tutors and administrators. Here are some questions that can help facilitate a conversation about a proposed project:

- What are the specific deliverables of your project? What exactly will be accomplished by the time you are finished

- What are some checkpoints we can establish as a means to measure your progress?

- What specific skills, knowledge, or qualification do you already possess that make this project attainable?

- Have you considered any additional support or resources you may need to ensure your project is realistic?

- What is the project deadline? Setting a deadline (even if it’s flexible) will help keep your project time-bound.

As an undergraduate tutor, I’ve relied on SMART projects to engage with writing center work beyond my basic tutoring responsibilities. In particular, everyone on staff for the summer at the UCWbL must propose and complete a project to ensure we are maintaining our workload when we have fewer appointments during our tutoring “offseason.” During the summer of 2019, I worked with the three other Heads to revise the model of a professional development workshop we facilitate as a part of our leadership duties. While working on this project with my colleagues, their mentorship was extremely beneficial to my understanding of our project—two of them had worked at the UCWbL longer than I had and they were able to relay their past experiences of facilitating the professional development workshop. Additionally, one of our program coordinators also collaborated with us on the project to provide additional guidance and insight. Having the opportunity to work with and be mentored by my colleagues on this project helped us keep it SMART and focused. Through our collaboration, we were able to specify exactly how we needed to revise our workshop model and outline the necessary steps to do so by the end of the summer. Being able to complete our specified goals promptly was beneficial to our entire workplace as we were able to implement the revisions that following Autumn Quarter. This would not have been possible without our team’s collaborative mentorship and SMART focus.

Professional development facilitators

Earlier I mentioned my writing center’s Head position and I’m aware that other institutions have their own versions of student leadership—this may range from specified “lead tutors” to graduate students who are employed solely to serve as workplace managers. Whatever the case, many centers have positions that allow student employees to work as formal leaders among staff. However, writing centers exist at a variety of institutions at many different scales, so it is not equitable to assume every administration can afford to financially compensate students for leadership work or even expect student employees to dedicate additional time per week to do so. With that said, how can we instill more accessible leadership opportunities in the center in a way that is both appropriate and equitable for both student tutors and administrators? One practical way to enact genuine student leadership is through opportunities to facilitate professional development.

Professional development can occur in several ways. At the UCWbL, we engage in professional development through workshops, guest lecturers, reading groups, and a variety of other interactive opportunities. This professional development can take place after the writing center is closed for the day for additional pay or during work hours when tutors have downtime on the schedule. In many workplace settings, professional development like this is often mediated by folks in authoritative positions—in a writing center context, this may include a director, program coordinator, or university faculty member. One way to shift this dynamic is by inviting student employees at the writing center to propose and facilitate professional development opportunities in collaboration with a writing center administrator. Trusting tutors with the opportunity to engage with and create content for professional development will help tutors feel closer to their administrators while also offering administrators a new perspective on what “professional development” means to their employees.

When student employees have the chance to engage in leadership through professional development, it does many things. First, it allows diverse student voices to be amplified through the content of professional development. Last year, I collaboratively facilitated a workshop on microaggressions in the writing center. As a biracial queer woman who has experienced microaggressions in academic and professional settings, I was able to share my unique and authentic perspectives with my peers who attended the workshop. My identities allowed the content of the workshop to be inclusive of the struggles of non-white and LGBTQ+ folks in the writing center. Additionally, when student employees have this opportunity, the professional development facilitator serves as a peer for participating tutors as opposed to an authoritative figure. As mentioned in the section on mentorship, this peer relationship allows for these experiences to extend beyond professional development and towards greater personal development as well. This personal connection to a professional development facilitator can help tutors feel safe to engage with the content more openly and authentically—ultimately allowing the professional development to be more effective. Finally, by engaging with this degree of leadership in the writing center, professional development facilitators can become inspired to continue a dedication to topics in writing center studies. Although every facilitator might not come out of their leadership experience aspiring to be a writing center director, there can be an increased dedication towards representing their voice in their specific writing center context. The more tutors actively engage with their writing center work, the more everyone benefits by learning about unique perspectives from a variety of diverse identities and experiences.

Rap sessions

The final step I propose to help bring diverse student voices to the forefront of writing center work is rap sessions. These sessions are often informal and allow participants to freely exchange knowledge, ideas, and feelings. For this article, I will discuss rap sessions that focus on discussing changes to writing center policies and procedures.

Like in most workspaces, it often makes sense for a single person (like a writing center director) or a small team of people (like a writing center operations team) to make the final call on decisions regarding policies and procedures. Folks in these positions have proved that they are qualified to make difficult decisions that impact their entire writing center community as they’ve been entrusted with these responsibilities. However, in some situations, these teams of decision-makers may benefit from feedback—a concept with which we’re all familiar. That’s where rap sessions come in.

In situations related to center policies and procedures, it may be most appropriate to elicit the thoughts, feelings, and ideas of writing center tutors before making long-term changes. As I mentioned earlier, tutors are the folks who do writing center work every single day. Therefore, tutor input on changes that impact day-to-day work can be extremely insightful. When considering something such as increasing appointment length or adding an appointment modality, understanding tutors’ unique perspectives on changes to their day-to-day work experience can be valuable for overall operations. Additionally, tutors may have certain identities or experiences that administrators don’t (or that administrators may not consider) that allow tutors to provide a diverse and representative understanding of various situations.

In the following tips for conducting and facilitating rap sessions, I am pulling from a guide created by Tulane University’s Office of Service Learning. Their specific guide is focused on obtaining feedback and insight from students participating in service-learning courses. However, much of this guide can be applied to writing center contexts because of the focuses on student participation and reflection.

Rap session guiding tips from the Office of Service Learning (2003):

- Establish a safe and confidential atmosphere

- Begin with an introduction to establish rapport among the group of participants

- Encourage openness and honesty

- Prompt other participants to answer questions posed during the session

- Determine an appropriate length for the session depending on the number of participants and the focus of the session

While following this guide, we must keep in mind that creating spaces that are safe, open, and honest is not as easy as it may seem. Because rap sessions are synchronous, tutors lose their anonymity and may not feel completely secure transparently providing feedback to writing center administrators. This means that in order to build a space in our centers where tutors can feel comfortable providing this kind of feedback, a previous relationship of mutual respect and trust must already be established prior to the rap session. The previous strategies mentioned in this article may be a means of developing the long-term rapport required to conduct an activity such as a rap session. If writing center administrators utilize mentorship, call for tutors to facilitate professional development, and collaborate with tutors on SMART projects, then tutors may feel they have the security to offer transparent feedback to their administrators on writing center policies and procedures without fear of punishment or judgment.

When administrators work to build long-term rapport with their tutors and host rap sessions based on these guidelines, they help create an honest space to receive tutor feedback on changes to policies and procedures. Ultimately, the entire writing center community benefits from these rap sessions because they allow tutors to be a part of the decision-making process by providing another opportunity for the representation of more voices.

Final Remarks

My suggestion of rap sessions ends on a note of coming together as a community to collaboratively solve problems. I leave you with this thought as a starting place. This paper highlights the issue of lacking diverse representation in writing center administrations and provides solutions through peer mentorship and actionable next steps. The scholarship, reflections, and suggestions that are woven into this work all push towards the goal of making writing centers places where truly every voice is not only heard but amplified. My concrete suggestions for writing center administrators stem from my perspective as an undergraduate tutor who feels inspired to work towards more just practices and greater representation for people like me. I encourage all of us to continuously consider how the work we do now will impact our communities in the future because I know—one next step at a time—we can work towards creating a field that authentically represents all the people it serves.

References

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). How to Tame a Wild Tongue. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, (pp. 53-64). Aunt Lute.

Barron, N., & Grimm, N. (2002). Addressing Racial Diversity in a Writing Center: Stories and Lessons from Two Beginners. The Writing Center Journal, 22(2), 55-83. www.jstor.org/stable/43442150

Campbell, C. M., Smith, M., Dugan, J. P., & Komives, S. R. (2012). Mentors and college student leadership outcomes: The importance of position and process. Review of Higher Education, 35(4), 595-625.

Denny, H. (2010). Facing Race and Ethnicity in the Writing Center. In Facing the Center: Toward an Identity Politics of One-to-One Mentoring, (pp. 32-56). University Press of Colorado.

Doran, G. T. (1981). “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives”. Management Review, 70(11), 35–36.

McManus, S.E. & Russell, J.E. (2007). Peer Mentoring Relationships. In Ragins, B.R. & Kram, K.E., The Handbook of Mentoring at Work: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 273-297). Sage Publications.

North, S. M. (1984). The Idea of a Writing Center. College English, 46(5), 433-446.

Office of Service Learning. (2003). Rap Session Guide. Tulane University.

Paré, A. (2002). Genre and Identity: Individuals, Institutions, and Ideology. In R. Coe, L. Lingard, & T. Teslenko, Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre (pp. 57-71). Hampton Press.

Postsecondary National Policy Institute. (2018, December 7). LBTQ Students in Higher Education. Postsecondary National Policy Institute.

United States Census Bureau. (2018, December 11). School Enrollment in the United States: October 2017 – Detailed Tables. United States Census Bureau.

Valles, S.B., Babcock, R.D., & Jackson K.K. (2017). Writing Center Administrators and Diversity: A Survey. The Peer Review, 1(1).