Mary F. McGinnis, College of Coastal Georgia

Jennifer P. Gray, College of Coastal Georgia

Abstract

The writing center and multimodal projects play an integral role in restoring justice to students and giving them ownership over their own voices. Too often, students, especially students who need extra writing support, come into the composition classroom believing that they are “bad writers” because they struggle with the traditional academic essay. Oftentimes, these students initially feel overwhelmed by any assignments they are asked to complete in a composition course. Prior to college, many students only have exposure to the traditional academic essay, which epitomizes “good writing” for them, and this lack of exposure to other kinds of composing causes students to carry the baggage of failure. This is where the writing center comes in. Providing additional training to writing tutors to prepare them to work with students on multimodal projects allows them to begin the work of restoring justice because the “job of the tutor is to help human beings…” (Fitzgerald & Ianetta, 2016, p. 167). Students sometimes show up in the writing center with an assignment that asks them to make a poster presentation for their biology course, a podcast for their English course, or a video for an education course. By coaching students on multimodal assignments and working students through feelings of intimidation and the baggage of previous writing courses, the writing center teaches students to repurpose their existing skills and overcome obstacles to become confident, capable writers and composers.

Keywords: writing center, multimodal, justice, voice, rhetoric, visual design, coaching, multimodal assignments, multimodality

The Importance of Multimodal Assignments

Multimodal assignments are compositions that allow students to engage multiple modes of communication. The New London Group (1996) explains that the different modes of communication include “audio design” (use of voice and music or sound effects), “spatial design” (how things are placed in a space), “gestural design” (movement and gesture), “visual design” (colors, fonts, images, etc.), and “linguistic design” (delivery, vocabulary) (p. 83). Often, these modes of design lead us to think of multimodal projects as digital projects, like audio slideshows; narrated presentations created in Prezi or PowerPoint; infographics created at Piktochart.com, Venngage.com, or Canva.com; websites made on Google Sites, Weebly, WordPress, or Wix; movies created with iMovie, Adobe Spark, Adobe Premiere Pro, or Movavi; diagrams; podcasts edited with Audacity or Garageband; or webtexts. However, multimodal compositions aren’t limited to just “new media” or digital projects. Jody Shipka (2011) elaborates, “…writing on shirts, purses, and shoes, repurposing games, staging live performances, producing complex multipart rhetorical events, or asking student to account for the choices they make while designing linear, thesis-driven, print-based texts can broaden notions of composing and greatly impact the way students write, read, and perhaps most importantly, respond to a much wider variety of communicative technologies–both new and not so new” (loc. 293-312). Analog multimodal projects may take a shape similar to Shipka’s (2011) iconic ballet shoes (loc. 198). These projects manifest as artifacts to support and advertise events organized by students (see Figure 1: Analog Multimodal Project Example. Donation boxes created for a student-planned and student-led clothing drive to benefit the residents of Safe Harbor Children’s Center, a home for abused and neglected youth in Brunswick, GA), collages, scrapbooks, poster presentations, or books with physical photos.

Students in our classes are asked to create infographics, podcasts, webtexts, hyperlinked word documents, and fully multimodal projects in a genre of their own choosing, which has generated scrapbooks, artifacts (flyers, emails, collection boxes) to support clothing drives, public service announcements, mini-documentary films, and an informational video for a local animal shelter, among other things.

Multimodal projects are being assigned more frequently, and this is a good thing. In 2020, it is essential that students develop the skills to communicate by whatever means necessary to reach their desired audiences. Cynthia Selfe (2004) asserts that “…if our profession continues to focus solely on the teaching only alphabetic composition–both online or in print–we run the risk of making composition studies increasingly irrelevant to students engaging in contemporary practices of communicating” (p. 72). To stay relevant, we need to update our teaching strategies. In addition, in the 2015 CCCC Chair’s address, Adam Banks asserts that it is time for us to retire the essay and to “realize that if we are going to fly and find new intellectual spaces and futuristic challenges to meet with our students and each other, we have to leave” the traditional essay and its comfort behind (p. 273). Moving forward with new challenges and new ways of composing with our students is what’s best for them and best for us. Incorporating multimodality into the FYC curriculum is necessary and will better prepare our students to be successful and to communicate to different audiences for different occasions in different mediums.

Not only are multimodal assignments important for students to complete to be able to compete in the 21st century, they’re also effective, and they’re especially effective with students who feel they are “bad writers.” Multimodal assignments appeal to students because they are meaningful, as they give students the opportunity to produce the types of texts they see and interact with every day. Moving past alphabetic text as a limitation, students realize that they are composing texts every day, whether it’s on a meme generator or on Instagram, Snapchat, or TikTok. The FYC classroom is a safe place for students to play and try something new while communicating to an audience.

Traditional essays are ‘school’ tools that are not used outside of school in most cases. As Yancey (2004) points out, “Our daily communicative, social, and intellectual practices are screen-permeated” (p. 305). When composing multimodal projects, students still make all of the same important rhetorical decisions about audience and purpose that they make when writing traditional essays. In fact, Shipka (2011) adds that students engage in a “complex and highly rigorous decision-making” process as they engage in multimodal composing (loc. 180). They just don’t have to compose in a tired, non-real-world five-paragraph essay format. Boscolo and Hidi (2007) report that students are intimidated by traditional essays and, as a result, are reluctant to complete them. In addition, students don’t see traditional papers as interesting and related to their lives (qtd in Darrington and Dousay, 2015, p. 29). Multimodal assignments, on the other hand, motivate students, rather than making them feel powerless.

Research shows that multimodal assignments are more appealing to students because they offer them more control over the assignment and they see how the assignment relates to their lives and future careers (Daniels, 2010; Lam and Law, 2007 qtd. in Dousay, 2015, p. 31). In addition, Dr. Gray (2015), in her scholarship, has found that students want other types of writing, “reflect[ing] a desire for engagement and choice. Students want to choose their topics and make the writing experiences something valuable to them. Students want to write in multiple formats” (par. 25). Providing students agency by giving them control over their topics, their approaches to composing, and their final product’s shape makes them more invested in what they’re doing.

Multimodal assignments give students a chance to revise prior conceptions of what makes “good writing.” The New London Group (1996) explains that new media can provide people with the “opportunity to find their own voices” (p. 71), and Shawna Coppola (2019) adds that this helps us “provide greater access for all learners” and avoid “potentially disengaging … students from the act of writing” (p. 18). In addition, multimodal assignments can save us from “act[ing] as self-appointed ‘gatekeepers’ who make dangerous, flawed decisions about whose voices are valued and whose stories are worth telling” (p. 18). Some students who struggle with the traditional essay will flourish and become confident composers when we allow them to operate in other genres. By expanding the definition of “good writing” and raising student awareness of their own composing, students have more options to find their own voices, important voices that are stifled by the privileging of print text. New media is not going to go away.

Preparing the Writing Center

In the 21st century workplace, our students’ future employers probably aren’t going to ask our former students to write papers for them. Instead, they’re going to ask for presentations, websites, data turned into handouts or graphics, videos, or other deliverables that require knowledge of multimodal composing. For example, Cengage (2018) reports that employers are looking for candidates with strong communication skills (p. 4). Multimodal assignments in first-year composition (FYC) will help students further develop the communication skills they already have by helping them learn the adaptability needed to be able to communicate to different audiences in the workplace. Adaptability, according to Dusenberry, et. al. (2015), is “defined by willingness” (p. 303). First, a willingness to “engage with the unfamiliar,” challenging “established communication practices” and using skills in new ways (p. 303). Second, a willingness to “become excellent mediators,” who can “mediate between the communicator’s purpose and the audience’s needs; negotiate the mode, medium, and message; and invite the audience to become a partner in the mediation” (p. 303). Adaptability is a communication skill that is necessary for success, and multimodal assignments foster this in students as they work with different technologies and become aware of the rhetorical decisions they make as they engage in communicating through these new technologies. Students become problem-solvers and savvy communicators.

Our college, among others, is aware of this and, in an effort to better prepare students for success both in the classroom and after college, has placed an emphasis on teaching skills that will facilitate success. For example, one of the General Education Outcomes on our college’s first-year writing syllabus focuses on adapting communication to different circumstances and audiences. This outcome can create space for flexibility, as communication can appear in more ways than simply a traditional essay. Rose (2015) reminds us of the need for adaptation, as “[w]riters encounter new contexts, genres, tasks, and audiences as they move among workplaces and communities beyond formal schooling, and these new contexts call for new kinds of writing” (pp. 59-60). Multimodal assignments can work to prepare students for these shifts in writing situations that exist outside of the school environment. In addition, we, as a part of our college’s Composition II curriculum assessment committee, as well as a system-level assessment project, have encouraged FYC teachers at our college to include one multimodal assignment in all sections of Composition II in an effort to update our FYC curriculum. In this way, we can provide best practices for composition via multimodal assignments and meet the assessment demands for the institution and regulating bodies.

As these assessment forces converged, we realized that the writing center would soon be receiving multimodal assignments. Our campus writing center is staffed by current students who are called “writing coaches.” We use the term “coach” instead of “tutor” as a way to resist the idea that the Writing Center only works with so-called “bad writers” who need to be tutored to pass a class. The job duties for a coach involve providing feedback and general outside perspectives about an activity, regardless of skill level. As we tell students, even the best athletes in the world have coaches because the athlete needs the feedback about her performance. Therefore, using “coach” in the writing center highlights that any writer at any skill level needs that type of feedback.

While the writing coaches were well-trained for a variety of disciplines, they were not as well-trained for a variety of assignment formats. The years of receiving traditional essays on our campus, such as the five-paragraph essay, had sculpted their comfort levels and experience. The coaches were quite used to providing feedback for the history student who was working on the five-paragraph essay on Ben Franklin or the compare/contrast paper on two literary characters. They could handle a biology lab report or an article critique for a nursing course. They saw countless sociology papers that explored a sociological theory enacted in life. However, up to this point, they really had not seen multimodal assignments, as they were not common on our campus. Dr. Gray, as a writing center director, had focused the coaches’ professional development priorities on the assignments they would most like see in sessions. However, in a professional development staff training session, only two of the five coaches reported having created a multimodal assignment, and not surprisingly, these two coaches had taken courses with Dr. McGinnis or Dr. Gray.

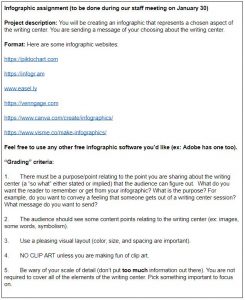

To remedy this lack of exposure to multimodal composing, Dr. Gray selected a common multimodal assignment that she knew at least three professors would be using during the upcoming term: the infographic. This professional development focus needed to study the genre of the infographic; therefore, she wanted to conduct this focus in a multimodal manner. Enacting the entity the coaches would be discussing seemed most effective. Also, the writing coaches needed to understand why multimodality was a sudden interest, so professional development had room for commentary about department assessment as well as large system-wide initiatives.

The first professional development moment focused on the infographic activity shown in Figure 2, where the tutors were asked to create an infographic that sent a message about the writing center. The activity provided links to popular infographic generating websites along with “grading” criteria. The writing coaches were given about a half hour to explore the listed resources and start creating something to be used for an example. Dr. Gray stressed the need to not expect perfection, as they were just getting something on the page for discussion. The coaches selected a “chosen aspect” of the writing center, and they developed the infographic to highlight this one item. The chosen aspects ranged in topic from feedback to kindness to community.

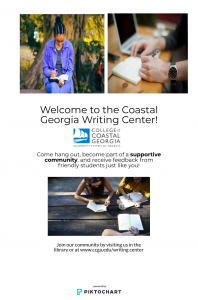

Figure 3 is an example of an infographic that is emblematic of writing coaches’ work–it depicted images of people reading and writing together with the text “Come hang out, become part of a supportive community, and receive feedback from friendly students just like you!” This infographic does a really nice job of emphasizing the community-centeredness of our writing center. The real magic of the training session happened as the coaches exchanged their work with each other to replicate a writing center session. Not only did they receive feedback about the effectiveness of their infographic or comments about weak layout choices, but they were most importantly reminded about what it was like to be a student, new to a genre or writing assignment because, as Muriel Harris (1992) points out, “Good tutors must be fellow learners

as well as fellow writers” (p. 380). Because the coaches were so experienced with the most common types of writing assignment on campus, having a new writing occasion like the infographic transported them into the shoes of an inexperienced multimodal writer. They were caught off guard. As Rose (2015) asserts, “Many people [including writing coaches] assume that all writing abilities can be learned once and for always. However, although writing is learned, all writers always have more to learn about writing” (p. 59). Feeling unstable, the coaches had plenty of questions, such as “what do I do?” or “how do I start?” They were in the moment of uncertainty and lacked confidence, and they really needed their writing coach partners to talk through the process of creation and revision. They needed the very work they provided in their typical sessions with students. While the coaches knew their work in the writing center was valuable, the training session confirmed this value for them and reinvigorated their practice.

As a side note, the process of watching the coaches create an infographic with their chosen concept was helpful for Dr. Gray in the writing center training. When observing writing coaches during sessions, we can get a sense of what is important to a coach, such as building confidence. Figure 4 is an example of this–it’s an infographic that showed how a writing coach may represent the concept of confidence. It depicted images of writing, sunrise, a road under a clear sky, a woman making a muscle, and a man holding a sign that says “prove them wrong.” The text focused on reaching goals and building confidence.

The action of selecting a concept to visualize via an infographic taught Dr. Gray a great deal of what feels important to a writing coach and what the coach sees as an end result of this action. For example, talking about “confidence building” with coaches or seeing a number on a satisfaction survey is helpful. Who wouldn’t like seeing a 95% student satisfaction rate under the category of “increasing confidence”? This concept often shows up in quantitative data all the time. However, it was meaningful to see the writing coach’s infographic about “confidence building” because it illustrated how the coach interprets “confidence building.” Here, confidence isn’t just about circling a number on a Likert scale; instead, the coach presented visual evidence of confidence: smiling students, tall postures, movement. The “confidence building” is more than a number and can mean more when it is presented as a visual instead of a statistic. Seeing the visual enriches our understanding of how the coach internalizes and represents the work of the writing center session.

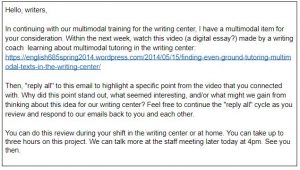

After participating in the infographic training session, we moved into learning more about the professional conversations regarding tutoring multimodal assignments. Instead of reading an article like other sessions in the past, we took a multimodal approach. Figure 5 shows an email that Dr. Gray sent to each coach asking her to view the video “Finding Even Ground: Tutoring Multimodal Texts in the Writing Center” by Heather Schultz (2014) that provided a historical and theoretical background for multimodal assignments and the writing center’s response to these new types of composing.

Then, Dr. Gray asked coaches to “reply all” via email (schedules prohibited a group staff meeting) and respond by highlighting a specific point from the video that they connected with, explaining why the point stood out, what seemed interesting about it, and/or what might be gained from thinking about the idea for the writing center. As Dr. Gray provided these questions, she hoped the coaches would find something interesting within at least one question. This professional development activity resulted in commentary about how to enact the practices Schultz discusses in her video. That is, treating multimodal projects as a “certain genre of text” and ensuring that coaches realize that they are “already master-adapters” who “already have the skills necessary to work with these non-traditional texts” (Schultz). Coaches envisioned how this would operate within our writing center and what technology platforms would be useful to suggest to students working on multimodal assignments.

Continued discussion also included staying current on other professional organizations centering on writing and instruction, such as the National Writing Project[1] . Figure 6 is an email that showed how Dr. Gray kept the coaches current with an example from the National Writing Program (NWP) initiatives that incorporated multimedia work. The NWP publicized the initiative permitting people to annotate the featured multimodal assignments from Detroit middle schools. Dr. Gray asked the coaches to review these projects and to be prepared to talk about the projects at the writing center’s next staff meeting.

In this case, it was important to show the writing coaches that this type of writing was not just something done on our campus on the whim of one instructor or because of a particular assessment task. This approach to writing is much larger than a one-time assignment in a first-year writing class. The training for multimodal coaching encouraged the coaches to join a much larger conversation about effective writing instruction.

As they progressed through the training, concerns naturally appeared, as the coaches were predicting potential weak spots and struggling on their own with the new type of writing. While there were some minor concerns mentioned regarding technology, such as what to do if a link failed, how to access a document via email or another platform, or a document would not open, the most common concern focused on not knowing the range of acceptability for the product. They just didn’t have a lot of models for this work, and they had little prior experience of their own to pull from as they responded to texts. The coaches were not sure what was acceptable in this type of writing, and they were afraid that they were sending a student to certain failure. They had no trouble knowing what was a “correct performance” for a typical five-paragraph essay genre, but they were less confident about what a “correct performance” was for a multimodal project. The tutors were relying on their past experiences with the five-paragraph essay genre, and these strategies and experiences did not necessarily track well into multimodal assignments. Lunsford (2015) explains prior experience with writing situations can be helpful sometimes, but if the writing professionals “rely on a strategy or genre or convention out of habit, that prior knowledge may not be helpful at all.” (p. 55). For the writing coaches, their prior work with the five-paragraph essay genre was not helping them broaden their approaches during multimodal assignments to figure out what “good” could look like in that situation.

This worry and inexperience led nicely into professional development opportunities for questioning the idea of what a “correct performance” looked like and how multimodal work pushes at the university’s concepts of standardized ideas of “good” or “bad writing.” These suggested opportunities range from staff meeting activities to guest speakers. Greenfield (2019) reminds us that there is no single “one-size-fits-all approach” and that our “experiences and strategies are necessarily and substantially contextual” (p. 10); therefore, these suggestions are not designed to be prescriptive but rather roomy jumping off points for individual center applications.

How Tutor Concerns were Addressed

To address the tutors’ concerns, Dr. Gray added tailored activities to staff meetings that focused on more practice and experience with multimodal assignments. The more multimodal samples writing coaches reviewed, the more at ease they became. We were able to look at sample podcasts, infographics, videos, and artistic pieces. Fitzgerald and Ianetta (2016) provide several strategies that can be used for multimodal projects (see pp. 172-176), and these sample questions and approaches were part of the staff meeting training activities. Again, these strategies, such as handling higher order concerns (HOCs) like focus first, are not written in stone. No matter what the assignment involves, the coach and the student work together to figure out what aspects of the project should be addressed during the session. Each project is unique, so each approach should be, too. The strategies are simply tools available to be used in sessions. After much repetition, the multimodal assignment will become less intimidating, as the coaches will have prior training experiences and strategies to call upon when working with a student with a multimodal project.

In addition, another option for training included inviting professors to staff meetings. At first, there were only two faculty members on campus that were assigning multimodal work (coincidentally, these two faculty members are the authors of this piece). However, we know students will begin to receive more multimodal assignments from other professors, due to the assessment initiatives in the department encouraging broadening assignment options for faculty teaching writing. A typical invitation included some assignment sheets and samples from the participating professor but also time for some question and answer discussion where coaches could bring up specific concerns they had about what was valued for that particular writing situation. Values shift based on this rhetorical situation, and as Adler-Kessner and Wardle (2015) assert, “[t]here are a number of individuals and groups asserting definitions of what ‘good writing’ is…” (p. 5). For example, a biology professor might value a blunt and clinical tone in the lab report, and a FYC professor might be looking for a more detailed and personal exploration in a podcast. During the staff meetings, the coaches were able to ask the professor what “good” writing meant in that situation. The coaches could see examples of what “good” included, and “good” certainly looked different for different classes and disciplines. Having the staff meetings with the invited professors illustrated this phenomenon in real time. The coaches could see that “good” was variable and that knowledge could be shared with the students. Denny (2010) explains that academic writing used in different courses can be “arbitrary, fluid, and subject to constant change” as “language is elastic and evolving” (p. 73). Realizing that “good” might change based on the course can be an empowering point to highlight during writing center sessions, and this information can help students adjust their writing based on the rhetorical situation within the class and assignment.

Tutoring on Multimodal Projects

These example projects come from a recent Composition 1 course. This student, Douglas, was asked to take an earlier project and remix it into a multimodal project. He chose to take his Project 1 Rhetorical Lens assignment, which was a written text, add some sources, and turn it into a podcast.

Figure 7 shows his initial Project 1 assignment, which is a rhetorical lens project written in Google Drive. A writing coach working with Douglas may have comments like these:

- In paragraph one, I appreciated hearing some specific details about you, such as your military service. This information helps me think about potential influences on your identity, and it shows you are thinking about your audience and what they know and don’t know about you.

- You can make your introduction stronger by getting more detailed about what you plan to discuss. For example, in your thesis at the end of paragraph one, you could identify the specific examples that make up your body paragraphs later on in the

Figure 7: Images of a traditional Student Project paper. That information will work to clue readers in to the points you plan to review.

- Your title has a semicolon error in it. Most of the time, we use semicolons to join two complete thoughts (ex: I was ready to leave the meeting; I started packing up my books.). Since the material before and after your semicolon are not complete thoughts, the semicolon isn’t the right choice. Many times, we can use a colon instead for titles (ex: Student Success: Exploring Approaches to Writing Instruction). Based on this sample, how might you adjust your title?

- You made a very powerful point in paragraph three (“And in seeing this realized that while I thought I was treating everyone fairly in fact I was not because I did not know the story that led people to the disease of addiction.”), and this statement is quite memorable. I would like to hear more about this important realization and how this change impacted you in the moment and after.

- How about a separate ending section? Right now I see your paper end with a long body paragraph that has one sentence at the end that sort of signals you are done with the paper (“Because of these realizations and the changes they have brought about, I feel that this has led me to be a better person and to communicate more effectively.”) This lack of a separate ending could be a problem, as readers might be expecting a wrap-up of some kind for essays. The ending paragraph is a separate section, and it usually restates the thesis and the main points you covered in the paper. It can also give readers a sense of what is important or memorable about your paper. What is something you’d like readers to remember about your topic/draft?

- After working through these items, let’s meet again in a day or two to review the changes and to talk about some of the remaining grammar and formatting concerns.

However, when a writing coach listens to and looks at the remixed version of the project, different considerations must be made. As Fitzgerald and Ianetta (2016) indicate, the work of the tutor can be different with multimodal projects, as there is “a far greater range of elements to respond to than you would with a writing-only text. Consequently, you would want to ask questions about design, visuals, and formatting that would consider these elements not as add-ons or lower-order but as essential parts” (p. 171). Figure 8 brings us back to our student’s example on his online portfolio. The coach may notice the document’s visual rhetoric first, seeing that there’s a large white space between the embedded podcast and the works cited section or that the works cited section is bullet pointed because hanging indents aren’t something that this website platform isn’t capable of.

Figure 9 is Douglas’s podcast in SoundCloud. The writing coach would listen to things like audio quality; his use of tone, pausing, emphasis, and intonation; the speed that he speaks; and his use of sounds, music, and/or silence. The coach has to “work through the text differently” and will “likely have additional questions to ask” (Fitzgerald & Ianetta, 2016, p. 173). In this particular podcast, the writing coach may notice the passion in Douglas’s voice and how that comes through particularly well in the podcast versus his original, written project. The podcast format enables Douglas to communicate passion more clearly and to add his personality into the assignment more thoroughly than the written assignment did. We hear Douglas’s authentic voice coming through differently in the podcast than we did in the written text. During a writing center session for this assignment, the coach might have comments like these:

- Tell me about your process for converting the writing-only text to the podcast. For example, how did you decide what areas in a sentence to stress? How did you decide when to drop your voice volume or take on a softer tone?

- Did you adjust the exact written material for the podcast from the writing-only text? If so, what did you change or add in that you felt you needed to do for the different format?

- How did you decide on the music option and how long to stay quiet at the start and at the end?

- I appreciate the pause between your opening information about yourself and the movement into the content of your podcast. This pause creates a separation that transitions the reader into the main heart of your paper.

- What questions do you have for me about your layout, format, or content?

In terms of the coach’s role, the questions for the podcast are broader than the writing-only text, including more comments and discussion about the rhetorical choices made by the author. In addition, there is less attention on formulaic concerns regarding the performance of the writer in a standardized essay genre, such as the need for a stand-alone concluding paragraph or forecasting information in paragraph one. Instead, the coach helps the writer see the control they have over the delivery of their message. This concept of control can be a powerful boost to the writer’s confidence.

As Schultz (2014) asserts at the end of her video, multimodal projects aren’t “wholly the same” or “wholly different” than traditional writing–they’re another genre that tutors can get to know. As multimodal assignments become more common and are included more thoroughly in writing center training activities, tutors will begin to see these projects as another genre and become more comfortable coaching students on these assignments.

Notes

- This organization focuses on providing professional development for writing teachers provided by other experienced and trained writing teachers. www.nwp.org ↑

Conclusion

This training is meant to be a beginning. As writing programs and English departments come into step with the field of Composition Studies and multimodality is further integrated into the curriculum, writing centers will have opportunities to become more acclimated to tutoring students on multimodal assignments. Our writing center plans to partner with new incoming faculty as well as faculty in other disciplines to better understand the types of assignments experienced on campus. An enormous amount of professional development occurred during the online shift in higher education due to COVID-19 in Spring 2020, so further professional development is expected as most tutoring will stay online and/or hybrid for some time. As coaches continue to work with multimodal assignments, we expect to see new questions and/or concerns. To predict some of these questions, future research directions could include a survey for WPAs to get a better sense of how many programs encourage and/or require multimodal assignments as a part of the curriculum. In addition, how are writing professionals and writing students experiencing this shift in assignments? As the traditional essay slowly moves into a phased retirement, professional development initiatives for writing center tutors (and writing faculty) will need to be cultivated.

Alongside the benefits of multimodal assignments, interacting with writing center tutors who have specialized training for tutoring students on multimodal assignments can further students’ confidence. Writing center coaching and multimodal projects specifically bolster students’ confidence as communicators and help them own their voices. The coach and the multimodal projects broaden the students’ understanding of their ownership over their work, highlighting the power students have over their writing. The students create materials not based on the number of paragraphs required but by what the readers may need and what message the writers want to send. These choices assist students in developing “the ability to write for purposes that are unconstrained and audiences that are nearly unlimited” (Yancey, 2004, p. 321), and that really is the goal of first-year composition.

References

Adler-Kassner, L, & Wardle, E. (2015). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies. Utah State UP.

Banks, A. (2015). Ain’t no walls behind the sky baby! Funk, flight, freedom. College Composition and Communication, 67(3), 267-279.

Cengage. (2018). The people factor: Uniquely human skills tech can’t replace at work. Cengage.

Coppola, S. (2019). Writing, redefined. Voices from the Middle, 26(4), 17-20.

Darrington, B., & Dousay, T. (2015). Using multimodal writing to motivate struggling students to write. TechTrends, 59(6), 29-34. doi:10.1007/s11528-015-0901-7.

Denny, H. (2010). Facing the center: Toward an identity politics of one-to-one tutoring. Utah State UP.

Dusenberry, L., Hutter, L., & Robinson, J. (2015). Filter. Remix. Make: Cultivating adaptability through multimodality. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 45(3), 299-322. doi:10.1177/0047281615578851

Fitzgerald, L., & Ianetta, M. (2016). The Oxford guide for writing tutors: Practice and research. Oxford.

Gray, J. (2015). What do students think about the five-paragraph essay? Teachers, Profs, Parents: Writers who care.

Greenfield, L. (2019). Radical writing center practice: A paradigm for ethical political engagement. Utah State UP.

Harris, M. (1992). Collaboration is not collaboration is not collaboration: Writing center tutorials vs. peer-response groups. College Composition and Communication, 43(3), 369-383.

Lunsford, A. (2015). Writing is informed by prior experience. In L. Adler-Kassner & E. Wardle (Eds.), Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies (pp. 54-55). Utah State UP.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard educational review, 66(1), 60-93.

Rose, S. (2015). All writers have more to learn. In L. Adler-Kassner & E. Wardle (Eds.), Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of writing studies (pp. 59-61). Utah State UP.

Schulze, H. (2014). Finding even ground: Tutoring multimodal texts in the writing center. Writing in a Digital Age.

Selfe, C. (2004). Toward new media texts: Taking up the challenges of visual literacy. In A.F. Wysocki, J. Johnson-Eilola, C. Selfe, & G. Sirc (eds.) Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for expanding the teaching of composition (pp. 67-110). Logan: Utah State Press.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a Composition Made Whole [Kindle Edition]. University of Pittsburgh P.

Stanford University Writing Center. (2019). Digital media consulting. Hume Center for Writing and Speaking.

Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication (56)2, 297-328.